Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Lusófona de Estudos Culturais (RLEC)/Lusophone Journal of Cultural Studies (LJCS)

versão impressa ISSN 2184-0458versão On-line ISSN 2183-0886

RLEC/LJCS vol.10 no.2 Braga dez. 2023 Epub 28-Fev-2024

https://doi.org/10.21814/rlec.4689

Thematic Articles

Patrícia Galvão: The First Female Brazilian Cartoonist

iPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Estudos Literários, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Although many male names have been recognised in the history of Brazilian comics, only some female figures are remembered. As such, this article aims to analyse two works by Patrícia Galvão: the album "Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte" (Birth, Life, Passion and Death) and the series of eight strips published in the newspaper O Homem do Povo, under the title "Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda" (Malakabeça, Fanika and Kabelluda). Better known as Pagu, Patrícia Galvão is now acknowledged as the first woman to publish comics in Brazil. "Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte” was produced when the author was just 19 years old and is an autobiographical graphic narrative, considered the first Brazilian comic written and drawn by a woman. Moreover, Pagu pioneered the production of female-authored, feminist-themed strips in Brazil when she introduced two distinct female representations in "Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda": the traditionalist wife and the young rebellious woman who defied conventional standards. Despite her innovation and prominent presence in the Brazilian cultural scene, Patrícia Galvão was - and sometimes still is - primarily recognised as a "modernist muse" or for her relationships with renowned writers. Thus, it is worth revisiting Patrícia Galvão's production since, as a woman and regardless of her connections, she produced highly relevant works communicating and disseminating feminist political messages and opposing gender discrimination and violence. It is, therefore, essential to acknowledge and reconsider the role of Patrícia Galvão/Pagu in the history of Brazilian comics.

Keywords Pagu; comics in Brazil; feminist strips; female cartoonists

Embora muitos nomes masculinos tenham sido reconhecidos na história dos quadrinhos brasileiros, poucas figuras femininas são lembradas. Nesse sentido, este artigo tem por objetivo a análise de dois trabalhos de Patrícia Galvão: o álbum “Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte” e a série de oito tiras publicadas no jornal O Homem do Povo, intitulada “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda”. Mais conhecida como Pagu, Patrícia Galvão é hoje reconhecida como a primeira mulher a publicar quadrinhos no Brasil. “Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte” foi produzido quando a autora tinha apenas 19 anos e configura-se como uma narrativa gráfica autobiográfica, a qual pode ser considerada como o primeiro quadrinho brasileiro escrito e desenhado por uma mulher. Além disso, Pagu inaugurou a produção de tiras de autoria feminina e com temática feminista no Brasil, ao trazer duas representações femininas diferentes em “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda”: a esposa tradicionalista e a jovem contestadora e fora dos padrões convencionais. A despeito de sua inovação e importância no cenário cultural brasileiro, Patrícia Galvão foi - e, por vezes, ainda é - frequentemente reconhecida apenas como “musa modernista” ou ainda pelas suas relações pessoais com escritores renomados. Assim, reexaminar a produção de Patrícia Galvão é necessário, uma vez que, enquanto mulher e independente de suas ligações, ela produziu obras de importância significativa na comunicação e na disseminação de mensagens políticas feministas e contra a discriminação e violência de gênero. Portanto, torna-se fundamental reconhecer e repensar o papel de Patrícia Galvão/Pagu na história dos quadrinhos brasileiros.

Palavras-chave: Pagu; quadrinhos no Brasil; tiras feministas; mulheres quadrinistas

Expression with its pleasure component is a displaced pain and a deliverance. (Bellmer, 1949/2022, p. 10)

1. Introduction

Bellmer (1949/2022), in Pequena Anatomia da Imagem (Little Anatomy of the Physical Unconscious or the Anatomy of the Image), suggests that the different modes of expression, including drawing and writing, result from a reflex. On a more practical level, the author provides the example of the diversion of physical pain, such as a toothache, through the impulse of closing the hand so hard that the fingernails pierce the skin. Thus, in the artistic field, creating an artwork would stem from an attempt to divert another pain. From a female perspective, this pain can easily be identified as the marginalisation imposed on women throughout history. Countless female artists have been omitted from the artistic canon solely for being women, and many women have been relegated to secondary roles as wives, lovers, or companions by dominant male figures. Therefore, women’s artistic creation is a liberation from the enduring constraints thrust upon them and stands as a testament to their resistance.

“I’ve always been seen as a sex. And I got used to being seen like that. ( ... ) I only regretted the lack of freedom that came with it, the unease when I wanted to be alone”, says Patrícia Galvão (2020, pp. 124-125), in Pagu: Autobiografia Precoce (Pagu: Early Autobiography), a lengthy confessional letter written to her husband Geraldo Ferraz at the end of the 1940s, while she was incarcerated. Belittled by a patriarchal tradition, the work of Patrícia Galvão - also known as Pagu - was condemned to oblivion until the 1980s, when an anthology, curated by Augusto de Campos (1982/2014), unveiled the multiple facets of the author. Emerging during a time when influential female figures in modernism - both Brazilian and international - hovered on the margins of male protagonists, Patrícia Galvão debuted in the modernist scene in 1929 as part of the anthropophagy movement. However, it was only with the publication of Campos’ research that she achieved broad literary recognition. With a wide-ranging production, Patrícia Galvão first appeared in the anthropophagy9 journals by initially contributing drawings, later expanding her involvement to include articles, illustrations, cartoons, and comic strips in the pamphlet newspaper O Homem do Povo and its section “A Mulher do Povo” (The Woman of the People). Following the newspaper’s discontinuation, she authored the novel Parque Industrial (Industrial Park; Galvão, 1933/2022) and continued to publish articles, chronicles and reviews in various newspapers.

It is remarkable how much of her output has been overshadowed, which is why it is important to revisit Patrícia Galvão’s production and promote it, making her known not for her appearance or her relationship with renowned writers but for her intellectual contributions as an author, particularly as a pioneering female (and feminist) figure in the creation of comic strips.

2. Female Artists and Cartoonists: Proscribed Figures

In graphic narratives, much like in other artistic domains, women play a significant role, yet their involvement is frequently disregarded or underestimated. It is widely acknowledged that the origins of comics trace back to an evolutionary progression rooted in the rise of cartoons - humorous and satirical drawings that started gaining traction during the 19th century. As cartoons developed, they evolved from mere illustrations with comedic content to taking the shape of short sequences with captions or speech balloons. This movement gave rise to strips, short sequential stories published in newspapers and magazines. The strips played a pivotal role in expanding visual storytelling, allowing stories to continue and characters to develop over time. This evolution ultimately gave birth to graphic narratives, the “comic”. Featuring sequential panels that combine text and artwork to tell more complex and detailed stories, comics have allowed their creators to explore various themes, transforming the genre into a powerful tool for artistic expression.

In the Western context, despite the presence of female creators throughout the many stages of the graphic narrative’s origins, which can be traced back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was only during the 1960s and 1970s that women started gaining widespread recognition. This period saw the emergence of a feminist movement within the realm of comics, where artists and writers used this form of media to explore themes related to gender and social issues. Nonetheless, pioneering artists such as Rose O’Neill (1874-1944), an illustrator who ventured into comic strips and was the creator of Kewpie (1909); Fay King (1889-1954), a cartoonist who pioneered autobiographical comics; and Marie Duval (1847-1890), recognised as one of Europe’s earliest female cartoonists; represent names that are frequently overlooked in historiographical collections of graphic narratives.

This critical marginalization has an even greater impact when we move away from the North America-Europe cultural axis. On the Brazilian scene, female names are scarce and overdue when looking for literature that systematises or categorises the history of comics in the country. In her article featured in the Revista Ártemis, Cintia Lima Crescêncio (2018) points out that the book Enciclopédia dos Quadrinhos (Comics Encyclopaedia; 2011), a compilation of the most significant figures in the genre worldwide, authored by Goida and André Kleinert, includes only 27 women. Among them, only nine Brazilian women are mentioned: Ciça, Chiquinha, Mariza, Erica Awano, Dadi, Edna Lopes, Maria Aparecida de Godoy, Adriana Melo, and Pagu. Apart from Pagu, all these artists are contemporary.

Very important names in the history and evolution of Brazilian graphic narratives have been left out, such as Nair de Teffé, who signed her cartoons as Rian and was the first Brazilian caricaturist (Campos, 1990), or Hilde Weber, a German artist who became a naturalised citizen after coming to Brazil and who in 1933 commenced publishing political cartoons in O Cruzeiro magazine. Crescêncio (2018) also points out that Pagu’s inclusion in the encyclopaedia may be attributed to her being perceived as a “rare graphic expression” or for being “Oswald de Andrade’s wife”, as the entry for the author reads as follows:

in the sole issue of the comics magazine Manga (PressEditorial, no date), which featured stories illustrated by Alain Voss, Marcatti, Jaz, Luiz Gustavo, and Péricles (Amigo da Onça), a striking curiosity emerged. Among the contents, the editors discovered five comic strips drawn by Pagu (Patrícia Rehder Galvão) for the newspaper Homem do Povo ( ... ). Pagu (also known as Oswald de Andrade’s second wife), a journalist, writer, and activist, contributed this rare graphic expression to the history of Brazilian comics. (Goida & Kleinert, 2011, as cited in Crescêncio, 2018, p. 69)

Regardless of her category in Goida and André Kleinert’s encyclopedia, Patrícia Galvão remains the first woman to have published a sequential graphic narrative in Brazil, earning her the distinction as the first Brazilian female cartoonist.

The evolution of comics in Brazil has followed a distinctive path. Their inception dates back to 1831, with publications of graphic humour in newspapers and magazines that satirised public authorities and the nation’s social customs. In 1855, the Frenchman Sébastien Auguste Sisson published O Namoro, Quadros ao Vivo, por S... o Cio (Dating, Live Pictures, by S... o Cio) in the magazine Brasil Ilustrado, the first comic strip in the country. Following this, Angelo Agostini, renowned as “the best, most important and most entertaining graphic artist the country had in the 19th century” (Campos, 2015, p. 202), published the first sequential comic strip featuring a recurring character, “As Aventuras de Nhô Quim ou Impressões de uma Viagem à Corte” (The Adventures of Nhô Quim or Impressions of a Journey to the Court). Between 1869 and 1870, the newspaper A Vida Fluminense published 14 stories about Nhô-Quim. Since then, many male names have found their place in various encyclopaedias about Brazilian comics, but few female figures have received recognition.

Patrícia Galvão, for example, was only recognised as the first woman to publish comics in Brazil when, in the 2000s, a group of female cartoonists got together to publish the magazine As Periquitas (2005). From then on, the name Pagu became popular among graphic narratives' enthusiasts. Pagu became not only the namesake of a publishing label for female artists but was also honoured with the HQ Mix award, often described as the “Oscars of Brazilian comics”.

However, it is worth noting that the editorial label Pagu Comics (Cândido, n.d.), launched on March 8, 2016, International Women’s Day, has been discontinued. Promoted by Editora Cândido through a partnership with Social Comics, a streaming service for reading digital comics, the imprint, created to house creations by women in Brazilian comics exclusively, has been cancelled. The imprint’s comics can no longer be found on the Social Comics website, and the imprint’s digital accounts on social networks such as Instagram, Twitter and Medium have not been updated since 2017. The HQ Mix trophy, meanwhile, paid tribute to Pagu in 2022. The award’s press release reads:

the 34th HQMIX Trophy honoured the 100th anniversary of the 1922 Modern Art Week. As such, the winners will receive the statuette of the character Kabelluda, by Patrícia Rehder Galvão, known as Pagu, one of the protagonists of the 1922 Modern Art Week movement. Pagu was a writer, poet, director, translator, illustrator, cartoonist, journalist and arts activist. She was the first woman in Brazil to draw comic strips. ( ... ) Pagu became the muse of the modernists and even married Oswald de Andrade in 1930. Together, they launched the “O Homem do Povo” newspaper, where she published her comic strips. (Redação, 2022, para. 1)

Once more, the artist’s name alone does not suffice. Despite being the first Brazilian cartoonist and making substantial contributions to the country’s cultural scene throughout the 20th century, Pagu is constantly referenced as a “modernist muse” or as Oswald de Andrade’s wife10. It is a fact that this invisibility and the tendency to associate women primarily with male figures stem from systemic structures of oppression that prioritise the male figure at the expense of the female. Simone de Beauvoir (1949/1967), in O Segundo Sexo: A Experiência Vivida (The Second Sex), asserts that women are imposed on the condition of the “other,” meaning they are not viewed as subjects equal to men. According to her perspective, this is a mechanism of male dominance that dictates what roles are or are not appropriate for women in an attempt to limit their space, their role in society and their constitution as a subject. Beauvoir also emphasises that this role, while evolving throughout history, is still a role of submission and hinders women from occupying public spaces that do not conform to the expectation of what is feminine. Thus, Beauvoir (1949/1970) describes man as autonomous and transcendent, while women are seen as immanent and states that, for this reason, women “have no past, no history, no religion of their own” (p. 13).

However, as highlighted by Gerda Lerner (1986/2019) in A Criação do Patriarcado (The Creation of Patriarchy), Beauvoir was wrong to think that women had no history. Lerner, who dedicated nearly two decades to studying women’s history, speaks of a “hidden history of women” (p. 302). She argues that the male version of history, legitimised as the “universal truth”, has depicted women as marginal to civilisation and victims of the historical process. The author states that “denying women their history reinforced the acceptance of the ideology of patriarchy and weakened the notion of individual women’s self-worth” (Lerner, 1986/2019, p. 304). Patriarchy, therefore, represents the silencing and concealment imposed on women in diverse artistic and cultural productions, including the medium of comics. Despite countless attempts to curtail their creative expression, many women have refused to take the historically assigned place of silence. Hence, it is essential to take a fresh look at the production and figures of these female artists, who should be appreciated for their creative contributions rather than their physical appearance or family associations.

3. The Pagu Album - Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte

Patrícia Galvão was born in 1910, moved to São Paulo in 1912 and enrolled as a student at the Escola Normal do Brás in 1924. The following year, at 15, she began drawing illustrations for her neighbourhood newspaper, the Brás Jornal, under the pseudonym Patsy. During this period, Galvão started socialising with names that later became influential figures in Brazilian literature and the arts, including Guilherme de Almeida, Mário de Andrade and Raul Bopp11. The latter published the poem “Coco de Pagu” (Pagu Coconut)12 in 1928, which prompted the writer’s nickname. The nickname, however, originated from a misunderstanding by the poet, who mistakenly believed that the honoured woman’s name was Patrícia Goulart.

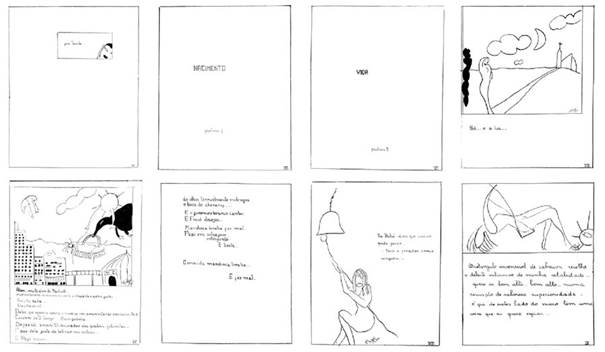

Immersed in Brazil’s flourishing modernist artistic and cultural scene, at the age of 19 in March 1929, Pagu published three drawings in the Revista de Antropofagia. During that same time, she desenhescreveu13 (drewrote) the album titled “Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte” (Birth, Life, Passion and Death). This hybrid work combined drawings, texts and captions and can be considered the first Brazilian comic written and drawn by a woman. In its original form, each drawing filled a page within a frame, where text and image interacted to weave a fantastical autobiographical narrative, reflecting the modernist ideals of its era. Augusto de Campos (1982/2014) observes a sharp perception of reality in the language of the texts, which oscillate between poetry, prose and captions, “all tinged with malice and sensuality” (p. 59). Pagu establishes a close connection between the verbal and the non-verbal, incorporating elements from cartoons, adverts, comics, cinema, and the modernist visual universe. Symbolically divided into four stages, the album “Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte” (Figure 1) anticipates the intention to organise the languages that, throughout her life and work, are not compartmentalised but engage in a continuous dialogue.

Source. From “Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte”, by Pagu, 1975, Código, (2), pp. 25- 26 (http://codigorevista.org/revistas/pdf/codigo02_digital.pdf)14

Figure 1 Opening pages of “Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte” (1929)

Pagu’s album was dedicated to Tarsila do Amaral and remained in her possession for many years until it was discovered by José Luís Garaldi in the library of one of Tarsila’s nephews and then published for the first time in the magazine Código, Number 2 (1975), 45 years after its creation. Subsequently it was published in the magazine Através, Number 2 (1978); in the book Pagu: Vida-Obra (Pagu: Life-Work) by Augusto de Campos (1982/2004); and in the compilation Croquis de Pagu e Outros Momentos Felizes que Foram Devorados Reunidos (Pagu’s Sketches and Other Happy Moments That Were Devoured Collected), edited by Lúcia Maria Teixeira Furlani (2004).

An autobiographical production, Pagu's comic shows how the author sees and portrays herself in the modernist spirit of the time bubbling up all over São Paulo. The daring attempt to combine text and image fitted in perfectly with the quest for originality imbued in modernism and put Pagu ahead of many since she was the pioneer of autobiographical comics in Brazil and also the first female cartoonist at a time when comics were not yet so popular in the country.

Based on her personal perceptions, “Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte” is a feminist narrative that addresses gender issues and female empowerment in an acidic and reflective way. When analysing this aspect in Pagu’s work, it is important to remember that one of the consensuses around the term “empowerment” outlined by Sarah Mosedale (2005) is that empowerment is a self-reflective act and can be facilitated through enabling conditions. Thus, the album Galvão produced, portraying herself as a female figure with desires, is regarded as an act of her own empowerment since, within the work, she establishes herself as a woman with agency over her body and desires. At the same time, this affirmation lays the groundwork for the empowerment of other women, as it affirms the existence of female figures who “own themselves” and are capable of participating and innovating in the cultural environment they inhabit to make their voices heard and share their experiences.

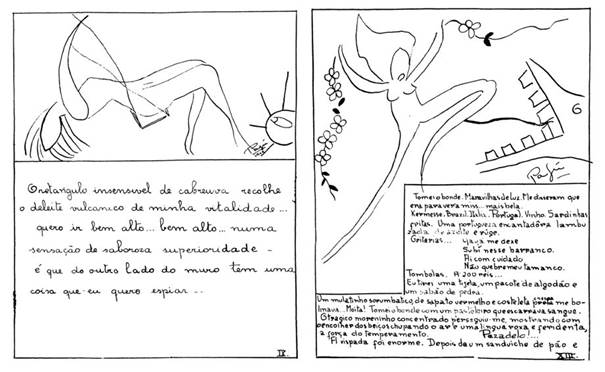

Despite the simple lines, Patrícia Galvão managed to convey the profound anguish brought on by her yearning for freedom in a society that stigmatised her because of her gender. Throughout the pages, she delved into themes such as female sexuality, the pursuit of autonomy, and harassment. For instance, on Page IX, Pagu’s drawing alludes to Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing. The French painting, which depicts the Baron of Saint-Julien in the company of his mistress, features a woman in the centre, sitting on a swing in motion. She mischievously tosses her shoe towards her lover, revealing her ankle. Sitting and leaning back in the lower corner of the screen is her lover, who is in the right place to see the young woman’s legs. However, the page drawn by Pagu (Figure 2) does not bear the euphemistic symbols of sensuality present in Fragonard’s painting. Patrícia Galvão shows a naked woman perched on a swing, and instead of a lover sneaking a peek in the lower corner, there is a sun. The swing is no longer an allegory of infidelity, as in the 18th-century paintings, but a symbol of freedom. The accompanying text on Pagu’s page makes it clear: “I want to go very high... very high... in a feeling of delicious superiority - because on the other side of the wall, there’s something I want to spy on”.

Despite the simple lines, Patrícia Galvão managed to convey the profound anguish brought on by her yearning for freedom in a society that stigmatised her because of her gender. Throughout the pages, she delved into themes such as female sexuality, the pursuit of autonomy, and harassment. For instance, on Page IX, Pagu’s drawing alludes to Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing. The French painting, which depicts the Baron of Saint-Julien in the company of his mistress, features a woman in the centre, sitting on a swing in motion. She mischievously tosses her shoe towards her lover, revealing her ankle. Sitting and leaning back in the lower corner of the screen is her lover, who is in the right place to see the young woman’s legs. However, the page drawn by Pagu (Figure 2) does not bear the euphemistic symbols of sensuality present in Fragonard’s painting. Patrícia Galvão shows a naked woman perched on a swing, and instead of a lover sneaking a peek in the lower corner, there is a sun. The swing is no longer an allegory of infidelity, as in the 18th-century paintings, but a symbol of freedom. The accompanying text on Pagu’s page makes it clear: “I want to go very high... very high... in a feeling of delicious superiority - because on the other side of the wall, there’s something I want to spy on”.

Source. From “Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte”, by Pagu, 1975, Código, (2), pp. 27- 28 (http://codigorevista.org/revistas/pdf/codigo02_digital.pdf)

Figure 2. Pages IX and XIII of “Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte” (1929)

Page XIII is Pagu’s depiction of a tram ride during which she is harassed: “I took the tram. Wonders of light. ( ... ) The tragic young swarthy man fixated on me and pursued me, showing the strength of his temper with a shrug of his lips sucking in the air and a fierce purple tongue. Nightmare!”. The drawing is significant: the protagonist is depicted naked, holding flowers and about to be bitten.

The body represented in the two figures and throughout the work is portrayed to convey a sense of female freedom. In the illustration on Page IX, the female figure surrenders to the swing, while on Page XIII, she seems to hover while an animalised figure tries to bite her. The entry on “Corpo” (Body) in the Dicionário da Crítica Feminista (Dictionary of Feminist Criticism; Amaral & Macedo, 2005) emphasises the growing awareness in contemporary feminism of the corporeality of the female body not as a “being”, but as a “field of interpretative possibilities” (pp. 24-26). In this sense, the body represented throughout the album portrays the female figure not as a submissive being, as she was supposed to behave at the time, but as a being detached from the “good manners” to which women were supposed to be subject, and free to move wherever she wants.

However, it is worth noting that Galvão distanced herself from the feminist movements of her era, which were split between the more elitist bias of Bertha Lutz and the anarchist perspective of Maria Lacerda de Moura.

On the one hand, Bertha Lutz, leader of the Federação Brasileira pelo Progresso Feminino (Brazilian Federation for Women’s Progress), advocated that including women in political participation would contribute to the nation’s progress without compromising domestic responsibilities and the social roles they traditionally played. Furthermore, the federation never clashed directly and publicly with the Catholic Church nor supported or repudiated political parties. On the other hand, Maria Lacerda de Moura, a great exponent of Brazilian anarchist feminism, challenged the precepts of the Catholic Church and patriotism and openly defended free love and sex education. Patrícia Galvão, however, falls into what Larissa Higa (2016) calls “solitary feminism” since she both repudiates the well-behaved feminism of the Federation and associates feminism with communism, which makes it impossible for her to relate to anarchist ideology. This solitary feminism is evident in the articles and strips published in “A Mulher do Povo” (1931).

4. “A Mulher do Povo”

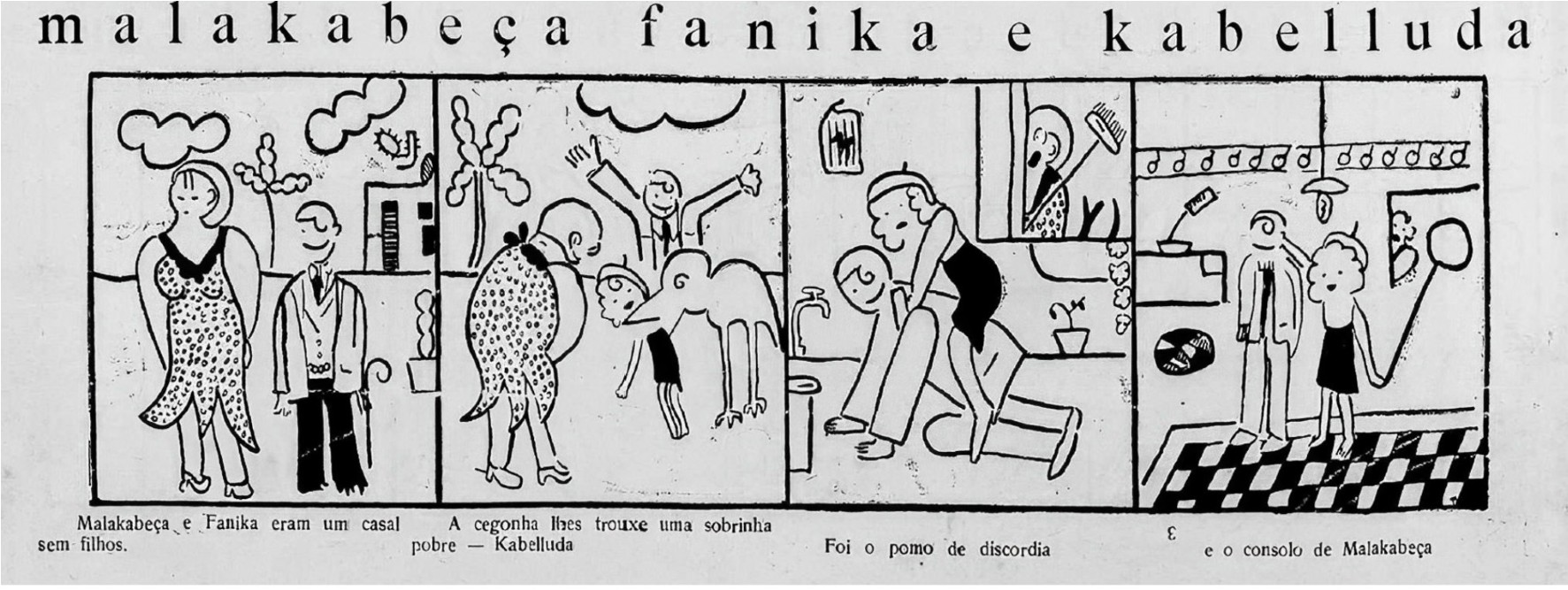

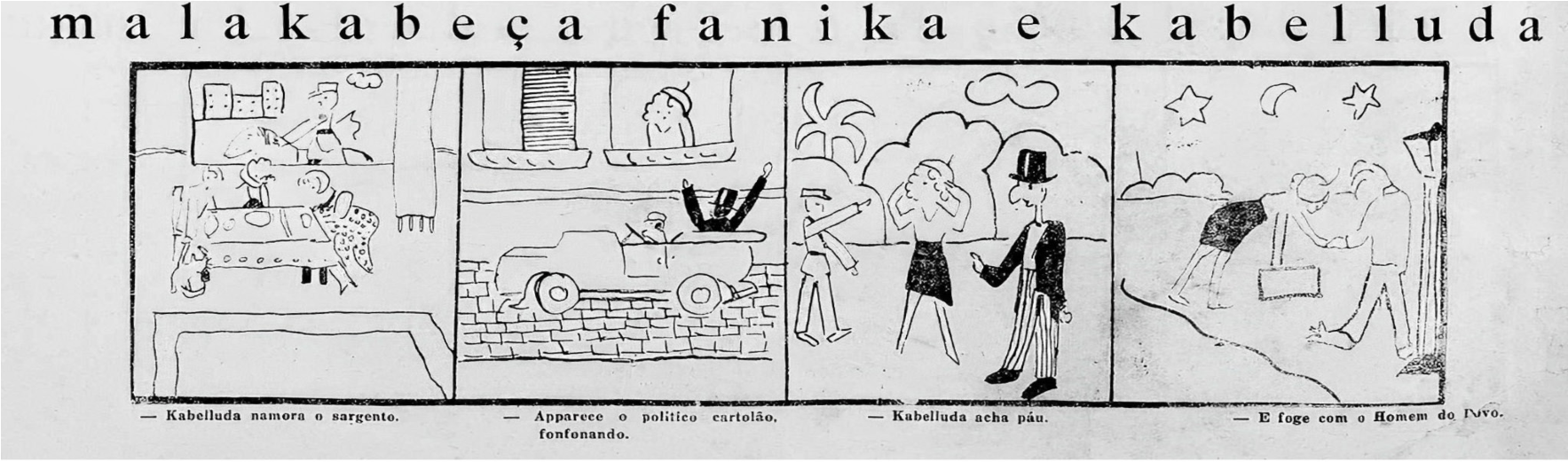

In 1931, when she first started editing the newspaper O Homem do Povo with Oswald de Andrade, Pagu, besides contributing articles, drawing various cartoons and the letters of the title of the section “A Mulher do Povo”, created a series of eight strips entitled “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda” (Malakabeça, Fanika and Kabelluda).

Before Patrícia Galvão, Nair de Teffé and Hilde Weber were prominent women in Brazil in producing cartoons and caricatures. Yet it was Pagu who inaugurated the production of female and feminist strips. In “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda”, the comic strip uses two types of female representation to symbolise the society of the time: the traditionalist wife and the young woman who challenges conventional norms. The strip has a pamphleteering tone and tells the story of Kabelluda, an unsubmissive young woman. After her newspaper closes, she is taken by a stork to her aunt and uncle, Malakabeça and Fanika, a bourgeois couple. Kabelluda arouses the jealousy of her adoptive mother, as Malakabeça fulfils her niece every wish (Figure 3). She becomes a communist revolutionary and organises a gathering in a public square, where she is ultimately arrested and shot but resurrected on the third day (Figure 4). After being reborn, Kabelluda decides to create a new newspaper. However, Fanika forbids it. Kabelluda flees to Portugal and returns to Brazil with a child whom her moralistic aunt does not accept. Finally, Kabelluda rejects a political boyfriend, runs off with a man of the people, insults a reactionary teacher and ends up lynched (Figure 5).

Source. From “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda”, por Pagu, 1931, O Homem do Povo, 2, p. 6. (https://memoria.bn.br/pdf/720623/per720623_1931_00002.pdf)

Figure 3 The second strip of the sequence “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda”

Source. From “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda”, por Pagu, 1931, O Homem do Povo, 4, p. 6. (https://memoria.bn.br/pdf/720623/per720623_1931_00004.pdf)

Figure 4 The fourth strip of the sequence “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda”

Source. From “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda”, por Pagu, 1931, O Homem do Povo, 7, p. 6. (https://memoria.bn.br/pdf/720623/per720623_1931_00007.pdf)

Figure 5

Pagu’s sequence of eight strips exposes the violence against the women of her time, who were censored, beaten and humiliated when they did not behave as expected. Patrícia Galvão seized on comics for political purposes and emphasised the subversion of customs. It can be seen right from the title: Malakabeça, the uncle who does his niece’s every bidding and is submissive to his wife’s impositions, could only be out of his mind; Fanika, the intemperate aunt who is never satisfied and zealously represses her niece’s behaviour; and, finally, Kabelluda, the strip’s protagonist, is a young revolutionary who questions institutions such as the church and marriage. With feminist ideals of freedom, the protagonist’s name can be associated with the pejorative adjective commonly associated with more radical feminists.

The drawing is neither proportional nor detailed, typical of old comics. Furthermore, the text is in caption format, a feature inherited from the language of cinema, which, in silent films, often pauses to read the characters’ lines. It is also important to remember that cinema and its technical characteristics greatly inspired modernist literature, a movement that Pagu followed closely. The simple line emphasises the humorous and satirical aspect that the author gives to the customs and stereotypes of the characters. An example is in Figure 3, where Kabelluda is carried by the stork by the neck and not in a basket. A strategy for amplifying an image’s potential for meaning, Pagu’s simple strokes produce frames that remove excessive information and accentuate specific details that either characterise stereotypes or make acid references to symbolic representations, as in the first frame of Figure 4, where Kabelluda is on a platform, or in the last frame when she is resurrected.

The themes addressed by the strip were in line with the perspective of the newspaper O Homem do Povo, which, from the outset, was promoted as a pamphleteering publication. Therefore, Patrícia Galvão viewed the strips as a playful means of criticising social traditions. However, as Augusto de Campos (1984) noted in his article “Notícia Impopular de O Homem do Povo” (Unpopular News of The Man of the People), the newspaper was not read by the working class, but rather by some intellectuals, law students, traditionalist mothers and the police, who eventually banned its circulation. Proudly playing her role in the newspaper, Pagu, besides her comic strips and cartoons, published feminist texts that satirised the traditional values and hypocrisy of the female bourgeoisie and São Paulo society. In “Maltus Alem”15, published in the newspaper’s first issue, Pagu expresses her indignation at the “elite feminists who deny the vote to labourers and uneducated workers” (Galvão, 1931b, p. 2). In the same issue, in Confessionário Burguês (Bourgeois Confessional), Patrícia Galvão (1931a) transcribes excerpts from a notebook belonging to a state school girl and concludes with the following comment:

while these empty-headed lunatics amuse themselves and openly spread their mentality by squandering on worthless and petty debauchery ( ... ) the money extorted from the poor labourers and workers, the latter crumble from dawn to dusk - conceiving a new generation of sick and mistreated oppressed people in the eternal transformation of sweat into cocktails. (p. 2)

Pagu’s scathing writings earned her a letter from Walkiria de Souza (as cited in Andrade & Galvão, 2009) on April 14, 1931, reproaching the author’s language and her criticism of young women:

I have a daughter at the State School whom I was teaching to be anti-religious and communist, according to the teachings of the Homem do Povo. But since you’ve messed with the girls, I wonder if it’s worth it to be antireligious and communist like this? (p. 53)

Walkiria also insisted on noting that the texts on communism written by men such as Hélio Negro, Raul Maia and Oswald de Andrade should be benchmarks for Patrícia Galvão. She went on to praise the newspaper, stating that “with the onslaught of the handsome young men, it gained popularity and became very well known” (de Souza, as cited in Andrade & Galvão, 2009, p. 53). Walkiria’s letter exposes exactly the hypocrisy that Pagu denounced in her strips featuring aunt Fanika and her writings in general. The newspaper had an atmosphere of bold provocation, marked by modernity and parody, which led to conflicts with law students and eventually resulted in the newspaper’s closure.

Following her journalistic pursuits, Patrícia Galvão authored the proletarian novel Parque Industrial (Galvão, 1933/2022) in 1933. She then wrote chronicles under the pseudonym Ariel for the newspaper A Noite. In 1945, Patrícia Galvão became part of the editorial team for the weekly Vanguarda Socialista and managed a section where she published articles connecting literary and political criticism. Additionally, she contributed a series of chronicles titled “Cor Local” (Local Colour) to Diário de São Paulo, which was part of the newspaper’s Sunday literary supplement. In this periodical, Pagu wrote studies and provided original translations of authors such as William Faulkner, Franz Kafka and James Joyce in the anthology section of foreign literature. She also produced some poems and contributed to Fanfulla and A Tribuna newspapers.

It is indeed astonishing that her substantial output has been neglected. Augusto de Campos (1982/2014), in his introductory text for the reissue of Pagu: Vida-Obra, emphasises that, despite her decisive, participatory and flamboyant role in the achievements of the literary field during the first decades of the 20th century, many women had their careers overshadowed by their female status.

5. Final Considerations

Much of Patrícia Galvão’s work remained inaccessible to the public for decades, either because her published texts were not reprinted or due to the existence of personal materials, such as the album made for Tarsila do Amaral, which only became public after Pagu’s passing. Despite her active involvement in the early 20th-century modernist movement, Patrícia Galvão was often discredited as an author and primarily celebrated as a “modernist muse” for a long time. She - who employed various pseudonyms, including Pagu, Mara Lobo, King Shelter, Ariel, and Solange Sohl - faced a delay in receiving recognition from literary critics for her work.

After her acknowledgement in the 1980s, Pagu became an inspirational figure across various art forms: her life story inspired musicians Rita Lee and Zélia Duncan to compose the song “Pagu”, released in 2000. There are also documentaries, films, plays, autofiction books and even a character in a miniseries inspired by Patrícia Galvão16. Her work has been extensively explored in academic circles regarding its political and feminist bias due to her militant work. However, research on her drawings - so dear to her work - is still scarce. As a result, Pagu’s identity as a cartoonist is an ongoing discovery that deserves further study and dissemination.

Comics have clearly played a significant role in culture and communication throughout history. However, women’s participation and contributions in this genre have often been neglected and made invisible. As such, this article sought to bring Patrícia Galvão to the fore, acknowledging her as Brazil’s first female cartoonist and highlighting two of her emblematic works: the album “Nascimento, Vida, Paixão e Morte” and the strips “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda”.

The recent growing popularity of graphic narratives has helped dissipating the stigma that once classified them as mere children’s entertainment, transforming them into a powerful platform for disseminating feminist political messages to combat gender discrimination and violence. Recognising Patrícia Galvão as Brazil’s first female cartoonist is crucial for addressing a historical gap and appreciating women’s vital role in culture and society. Furthermore, the historical retrieval of graphic narratives crafted by Brazilian women maps the diversity and complexity of the female experience over time, providing inspiration and empowerment for forthcoming generations of female artists. By showcasing and spotlighting the work of Patrícia Galvão, this article seeks not only to promote the author but also to amplify the voices of emerging female artists and foster research dedicated to recovering and disseminating the creations of other women who have defied patriarchy through comics.

In short, the history of comics in Brazil must encompass the contributions of women, beginning with the pioneering work of Patrícia Galvão. Acknowledging her legacy represents a pivotal first step towards correcting the invisibility of female productions and paying homage to the women who have enriched culture and society through this medium.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Rudá K. Andrade and Leda Rita Cintra for generously granting the use of the images in this article. I would also like to extend this thanks to Ariane Stolfi, Bruno Schiavo, Daniel Scandurra, Gabriel Kerhart and João Reynaldo for the remarkable project of digitising and publishing online the twelve issues of Código magazine, edited from 1974 to 1990 by Erthos Albino de Souza. This collective effort made it possible to access a valuable collection that has substantially enriched this research.

REFERENCES

Amaral, A. L., & Macedo, G. (2005). Dicionário da crítica feminista. Edições Afrontamento. [ Links ]

Andrade, O., & Galvão, P. (2009). O homem do povo. Imprensa Oficial do Estado. [ Links ]

Beauvoir, S. (1967). O segundo sexo: A experiência vivida (S. Milliet, Trad.). Difusão Europeia do Livro. (Trabalho original publicado em 1949) [ Links ]

Beauvoir, S. (1970). O segundo sexo: Fatos e mitos (S. Milliet, Trad.). Difusão Europeia do Livro. (Trabalho original publicado em 1949) [ Links ]

Bellmer, H. (2022). Pequena anatomia da imagem (G. Dantas & M. R. Salgado, Trads.). 100/cabeças. (Trabalho original publicado em 1949) [ Links ]

Campos, A. de. (1984). Posfácio: Notícia impopular de O Homem do Povo. In O. Andrade & P. Galvão (Eds.), O Homem do Povo (pp. 55-59). Imprensa Oficial do Estado. [ Links ]

Campos, A. de. (2014). Pagu: Vida-obra. Companhia das Letras. (Trabalho original publicado em 1982) [ Links ]

Campos, M. de F. H. (1990). Rian: A primeira caricaturista brasileira (primeira fase artistica: 1909-1926) [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade de São Paulo]. ReP. [ Links ]

Campos, R. (2015). Imageria: O nascimento das histórias em quadrinhos. Veneta. [ Links ]

Cândido. (s.d.). Pagu Comics. http://candylivros.com.br/pagucomics.html [ Links ]

Crescêncio, C. L. (2018). As mulheres ou os silêncios do humor: Uma análise da presença de mulheres no humor gráfico brasileiro (1968-2011). Revista Ártemis, 26(1), 53-75. https://doi.org/10.22478/ufpb.1807-8214.2018v26n1.42094 [ Links ]

Furlani, L. M. T. (2004). Croquis de Pagu - E outros momentos felizes que foram devorados reunidos. Unisanta. [ Links ]

Galvão, P. (1931a, 27 de março). Confessionário burguês. O Homem do Povo, (1). [ Links ]

Galvão, P. (1931b, 27 de março). Maltus Alem. O Homem do Povo, (1). [ Links ]

Galvão, P. (2020). Pagu: Autobiografia Precoce. Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Galvão, P. (2022). Parque industrial. Companhia das Letras. (Trabalho original publicado em 1933) [ Links ]

Higa, L. (2016). O feminismo na obra da jovem Pagu. In C. Rodrigues, L. Borges, & T. R. Ramos (Eds.), Problemas de gênero (pp. 443-452). Funarte. [ Links ]

Lerner, G. (2019). A criação do patriarcado: História da opressão das mulheres pelos homens (L. Sellera, Trad.). Cultrix. (Trabalho original publicado em 1986) [ Links ]

Mosedale, S. (2005). Policy arena. Assessing women’s empowerment: Towards a conceptual framework. Journal of International Development, 17, 243-257. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1212 [ Links ]

Redação. (2022, 10 de agosto). Estatueta do 34º Troféu HQMIX homenageia a Kabelluda de Pagu. Correio do Cidadão. https://www.correiodocidadao.com.br/curta/ estatueta-do-34o-trofeu-hqmix-homenageia-a-kabelluda-de-pagu/ [ Links ]

1An offshoot of the “Modern Art Week”, the Revista de Antropofagia was launched in São Paulo in May 1928 and ended publication in August 1929. The journal represented the cultural movement with the same name, which sought to create art and literature embodying national traits. Its issues can be accessed through the digital collection of the Biblioteca Brasiliana (https://digital.bbm.usp.br/handle/bbm/7064).

2Oswald de Andrade (1890-1954) was one of the protagonists of Brazilian modernism and the leading architect of the anthropophagic movement, which proposed a reinterpretation and assimilation of European culture by Brazilian artists to forge a unique cultural identity for the country. He was a journalist and author of poetry, prose, essays and theatre, whose work was characterised by experimentalism and social and political criticism.

3Guilherme de Almeida, Mário de Andrade and Raul Bopp were important organisers of the 1922 “Week of Modern Art” and distinguished poets and critics in the Brazilian cultural landscape.

4“Coco de Pagu”, a poem by Raul Bopp, was published on October 27, 1928, with an illustration by Di Cavalcanti sketching Patrícia Galvão playing the guitar, in the magazine Para Todos, Year X, Number 515, Rio de Janeiro.

5A neologism, created by Augusto de Campos (2014, p. 93) in eh pagu eh to define the artistic process developed by Patrícia Galvão.

6The album was first published in the magazine Código, Issue 2, Salvador, 1975. Today, not only has the album been reproduced in various books about Pagu, but it is also available on the website http://www.codigorevista.org/nave/: a project to digitise and publish online the 12 issues of the magazine Código, published from 1974 to 1990, by Erthos Albino de Souza.

8In 1982, a 15-minute mini-documentary titled Eh Pagu, Eh! directed by Ivo Branco focused on Pagu’s life. In 1988, the film Eternamente Pagu (Eternally Pagu; 110 minutes), directed by Norma Bengell, set out to tell the author’s life story. In 2004, Pagu was depicted as a character in the miniseries Um Só Coração (One Single Heart), played by Míriam Freeland. In 2022, Adriana Armony released the book Pagu no Metrô (Pagu on the Subway), an autofiction that intertwines Armony’s research with Galvão’s time in France. The same year, the play Pagu - Até Onde Chega a Sonda (Pagu - How Far the Probe Reaches) premiered in São Paulo The play draws inspiration from an unpublished manuscript by Pagu and delves into her thoughts and reflections during her imprisonment in 1939.

Received: March 31, 2023; Accepted: July 10, 2023

texto em

texto em