Within the research on the social psychology field, behavioral sentences/descriptions or episodic information are materials historically used. For instance, these materials have been used within impression-formation paradigms, in which participants form impressions about a hypothetical person based on sentences that describe his/her behavior (e.g., Garcia-Marques et al., 2012); to study stereotypes, either its content or the cognitive processes underlying them (e.g., Hewstone et al., 1994; Hamilton et al., 1990); to study the incongruency effect, where a given trait or category is initially activated, and then expectancy congruent, incongruent, and/or neutral sentences are presented (e.g., Hastie & Kumar, 1979; Garcia-Marques & Hamilton, 1996); to study spontaneous trait inferences (STI; e.g., Todorov & Uleman, 2004); or in the face memory field, to study the role of behavioral information on people’s memory for faces (e.g., Mattarozzi et al., 2019).

A behavior, seen, read, or heard, can mean different things depending on the stereotypes someone holds about a social group and its members (Hamilton et al., 1990). A stereotype is a cognitive structure/category that each person has, composed of accumulated knowledge, beliefs, and expectancies about social groups, and not necessarily accurate or well-adjusted to all group members (Allport, 1954; Devine, 1989; Katz & Braly, 1933). Sereotypes influence expectations, information processing, affective evaluations, social categorization (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2010; Fyock & Stangor, 1994; Hamilton et al., 1990), just to name a few. For example, Neuberg (1989) found that in a job interview, interviewers in a negative-expectancy condition (vs. no-expectancy) without a goal (vs. accuracy goal) formed more negative impressions about applicants. Besides the influence of stereotypes on expectations, they also influence inferences and attributions (Hamilton et al., 1990). Sagar and Schofield (1980) found that 6th grade White and Black preadolescents interpreted ambiguous social behaviors as meaner or threatening when the actor was Black (compared to White actors). In another study where whites watched a video that portrayed a discussion and an ambiguous shove, Duncan (1976) found that participants made more personal attributions to the harm-doer when he was black and the victim was white, compared to all the other possible combinations between race and harm-doer/victim. When it comes to the saliency of racial categories, Todd and colleagues (2021) found that race saliency led black males’ faces (vs. white) to bias participants when identifying an object as a gun (vs. tool). Overall, these cases exemplify some types of studies and stimuli that use stereotypes, directly or indirectly, as an object of study.

To examine the effects of stereotypes on information processing, researchers have traditionally used faces (with different poses, light/brightness, expressions), lists of words, attributes, photographs, and written behavioral descriptions. And within behavioral descriptions, there is also a wide variety: there are pre-tested stereotypic behaviors for gender (Cipriano et al., 2021), intersectionality between gender and age (Cipriano et al., 2021), for trait dimensions like sympathy and intelligence (Garrido, 2003), several professional groups (Santos et al., 2017), valence manipulations (Bliss-Moreau et al., 2008; Brambilla et al., 2019). However, as far as we know, there is a lack of updated and validated racial behavioral descriptions for both the Portuguese and the American populations.

In fact, according to 2016 data from the Science and Technology Observatory (2019), a direct consequence of this lack of updated racial behavioral information is the dissemination of the Afro-American stereotypes content and consequence effects in the related literature, for instance, it has been frequently assumed that the content of the Afro-American stereotype is the same as that Black stereotype. Fiske (2017) remarked that race and ethnicity tend to be more societal constructed categories (compared to age and gender), thus being more vulnerable to the influence of history. Further, given the racial historical realities, both in the United States of America and Portugal, there are reasons to suspect that the stereotype of Black and African-American is not the same, in both countries, and thus should not be treated as interchangeable concepts.

The first historical reports of massive slavery in Portugal date back to the middle of the 15th century (Jordan, 2014; Lipski, 2009), during the Age of Exploration, also known as the Age of Discovery. By this same time, the “Portuguese ships began supplying the Spanish and Portuguese settlements in America with Negro Slaves” (Jordan, 2014, pp. 33-34). And it was only in 1773 that Portugal was the first country in Europe to begin the gradual emancipation of slaves, despite complete abolition having only been achieved about a century later (Marques, 2020). Slavery in the United States of America was abolished at the time of the American Civil War by Abraham Lincoln in 1863 through the Emancipation Proclamation. Despite this, the American history of the last century continued to be marked by the troubled relationship between Whites and Blacks. Freom Rosa Parks bus boycott that started the modern civil rights movement, in 1955, to the “I Have a Dream Speech” of Martin Luther King, in 1963, to more dramatic events marked, for example, by the shooting of Amadou Diallo, a West-African immigrant wrongly suspected of rape, and to whom the police fired forty-one shots (Correll et al., 2002; Glennon, 1991).

Given this shared history, but also weighing more recent events, there’s support for the existence of two different stereotypes, Black vs. Afro-American, even though there are possible similarities. In 1991, Hecht and Ribeau found differences between the semantic labels selected by Black Americans. In the article, they found that about 46% of respondents described their ethnic/racial identity with the “Black” label. While only 22% identified themselves as “Afro-American”. Participants self-identified with the “Black” label described they were taught to do it, they accepted it, and when compared to the mainstream American culture, they showed mild patriotism. On the other hand, participants who self-identified with the “Afro-American” label emphasized their dual cultural heritage - Black or African descent and American. Interestingly, the self-identified Afro-Americans not only exhibited to be the most nationalistic group, as their ratings of cultural superiority were also the highest (Hecht & Ribeau, 1991).

Additional support for the existence of two stereotypes comes from Fiske (2017) who organizes stereotypes in a warmth-competence space. As she refers to, generically, black people tend to be moderately evaluated in a warmth-competence space, in countries like Portugal, Spain, Italy, and even in the United States, however, Americans also deal with subtypes of Blacks: the poor (low warmth and low competence) and the rich (high warmth and high competence; Fiske et al., 2009) (Fiske, 2017).

Given the proliferation and domination of African-American stereotypes in the literature, as mentioned above, the starting point of this paper was the assembly of the attributes representing the content of racial stereotypes. Whites tend to be described with attributes such as ambitious, boring, greedy, industrious, materialistic, selfish, and successful; while Blacks, presumably African-Americans given the country where the data were collected, tend to be associated with attributes such as athletic, criminal, dangerous, ignorant, lazy, poor, and rhythmic (Donders et al., 2008; Katz & Braly, 1933; Petsko & Bodenhausen, 2019; Plant & Devine, 1998; Wolsko et al., 2000, Fairchild, 1985).

Given the negative valence of the attributes associated with the African-American stereotype, it is also quite probable that the content of the stereotype associated with black Americans is riddled with negativity. In fact, Devine and Elliot (1995) had already noted that in their research. In the same vein, Livingston and Brewer’s (2002, Exp. 1) findings support this conclusion since the authors showed that facial primes of high prototypical Blacks facilitated more negative evaluations than low prototypical Black faces or Whites. Fazio et al. (1995) also reported that priming participants with black faces (compared with white faces) facilitated responses to negative adjectives. And Falvello et al. (2015) found that participants rated faces paired with negative behaviors as less trustworthy than faces paired with positive and neutral behaviors. Considering previous arguments and the evidence already obtained, it is also important to address the valence effects associated with black stereotypes in studies involving these and related behavioral descriptions.

Summing up, and given the wide application of this type of material, the two main goals of the present work are (1) present a set of behavioral descriptions pre-tested for race stereotypicality and valence in an American sample and a Portuguese sample; (2) examine whether the two samples differ in their perceptions of racial stereotypicality and valence.

Experiment 1

The goal of the first experiment was to develop and pretest a set of stereotypical behavioral descriptions of whites and blacks and assess the valence of each description in the American population.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 31 participants (16 females, 13 males, one transgender, and one who preferred not to specify; M age=28.8 years, SD age=5.1 years) recruited via Prolific platform. Participation required the fulfillment of the following criteria: (a) self-identified as Caucasian, (b) born and lived in the United States, (c) completed at least 10 studies on Prolific, and (d) an approval record of at least 90%. They paid for their £3,13 (approx. $3.93) participation.

Material

From Petsko and Bodenhausen (2019), we first selected 16 personality traits. Four stereotypical traits of Black Americans (two positives, i.e., P; and two negatives, i.e., (N): athletic (P), talkative (P), loud (N), and poor (N). Four counter-stereotypical traits of Black Americans: scientifically-minded (P), quiet (P), shy (N), and yielding (N). Four stereotypical traits of Whites: conservative (P), ambitious (P), arrogant (N), and conceited (N). And four counter-stereotypical traits of Whites: open-minded (P), rhythmic (P), low in intelligence (N), and physically dirty (N).

After the selection of the personality traits, we searched the literature for existing illustrative behavioral descriptions of the selected traits. From this search, we selected and adapted behavioral descriptions from Hamilton et al. (1989), Fuhrman and colleagues (1989), Ferreira and colleagues (2005), Garrido (2003), Jerónimo and colleagues (2004), Osterhout and colleagues (1997), Orghian and colleagues (2018). Additionally, we (i.e., the research team) also generated a number of behaviors that we believed to illustrate these traits.

Overall, 154 trait correspondent behaviors were created. Before testing, all these behaviors were adjusted by a native English speaker to have an American style.

Procedure

The participants signed up for a Qualtrics study named “Intuitions about culturally shared beliefs”. First, participants were informed that their participation was entirely voluntary and that their responses were anonymous and confidential. After providing their informed consent, participants received the task instructions. In the first phase, they saw 154 random-order descriptions of behaviors describing everyday activities in the center of the screen and for unlimited time. To judge the stereotypical degree of each behavior, participants rated how likely each behavior was to have been performed by a White or a Black person. Additionally, we gave the following information:

“When you are rating those likelihoods, please use your intuitions about what the average American believes (namely, what you think other Americans in general think), regardless of whether you, personally, agree or disagree with those beliefs.”.

Participants made their judgments on a semantic differential with the following anchors: 1 - “Extremely likely of Whites”, 5 - “Equally likely of Whites and Blacks”, 9 - “Extremely likely of Blacks”.

In the second phase of the study, participants saw the same set of behaviors, but the task was to evaluate the valence of each using a rating scale having as anchors: 1 - “Extremely negative, 5 - “Nor negative neither positive” and 9 - “Extremely positive”.

At the end, participants completed some socio-demographic questions (age, gender, race, and educational level). Then they were thanked and debriefed.

Results and discussion

For each behavior, we compared the mean stereotypicality ratings and the mean valence ratings against the scale midpoint (5) using one-sample t-tests. Results can be found in Appendix 1 and the selected behaviors are identified in it.

Briefly, these analyses yielded the following results (see Appendix 2): 34 behaviors were considered stereotypical of the black category, of which 16 are positive (e.g., Scored the winning touchdown for his football team.) and 18 are negative (e.g., Everything he does makes an incredible amount of noise.); 39 stereotypical of white, of which 26 are positive (e.g., He prefers classical music instead of pop music.) and 13 are negative (e.g., Some consider his voice shrill and high-pitched.); and 52 neutral behaviors, 19 positives (e.g., Lifts weights at the local gym every day.) and 33 negatives (e.g., He didn’t shut up for a second.).

Since participants’ stereotypicality ratings were made on a semantic differential varying from 1 (Extremely likely of Whites) to 9 (Extremely likely of Blacks), with 5 corresponding to the response of “Equally likely of Whites and Blacks”, to directly compare the stereotipicality judgments of whites and blacks, we had to invert the values of white judgments so that higher judgments (in absolute values) meant more stereotypicality for both categories. So, firstly, we created two new variables based on the average judgments, one related to stereotypicality (average judgments less than 5 were labeled as stereotypical of white, average judgments greater than 5 were labeled as stereotypical of black) and another to valence (average judgments less than 5 were labeled as positive, average judgments greater than 5 were labeled as negative). Secondly, we subtracted 5 from each average judgment to recenter around 0, i.e., the new middle point of the scale. Then, we calculated the absolute value of each average judgment, thus allowing stereotypical behaviors comparisons.

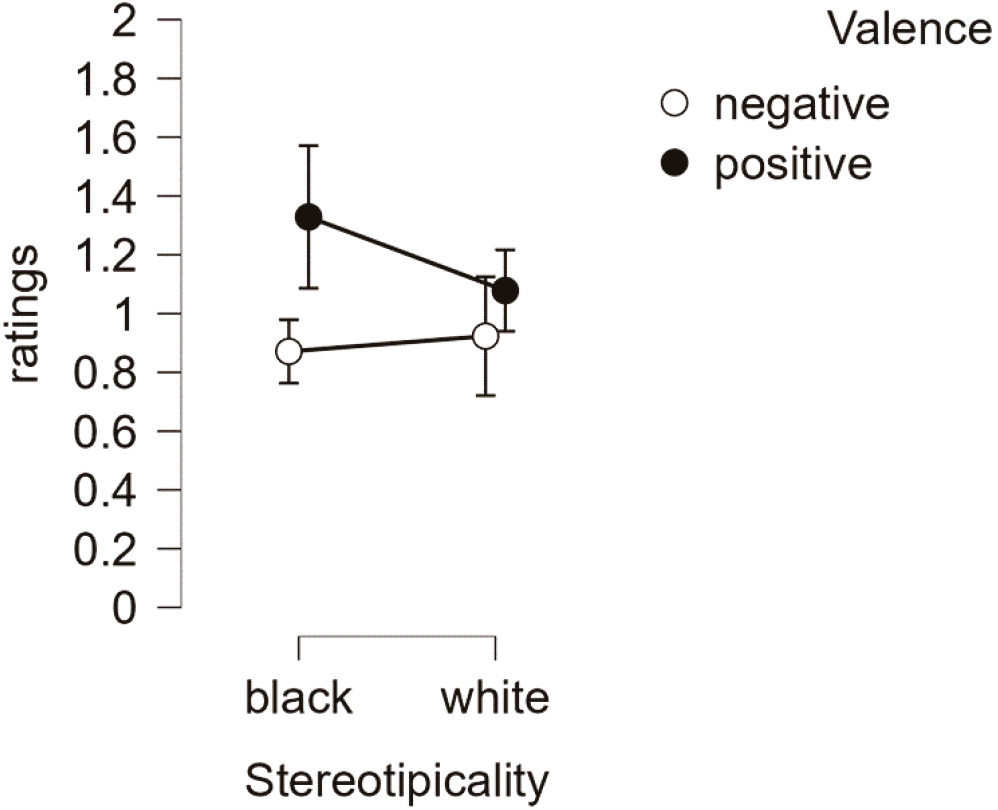

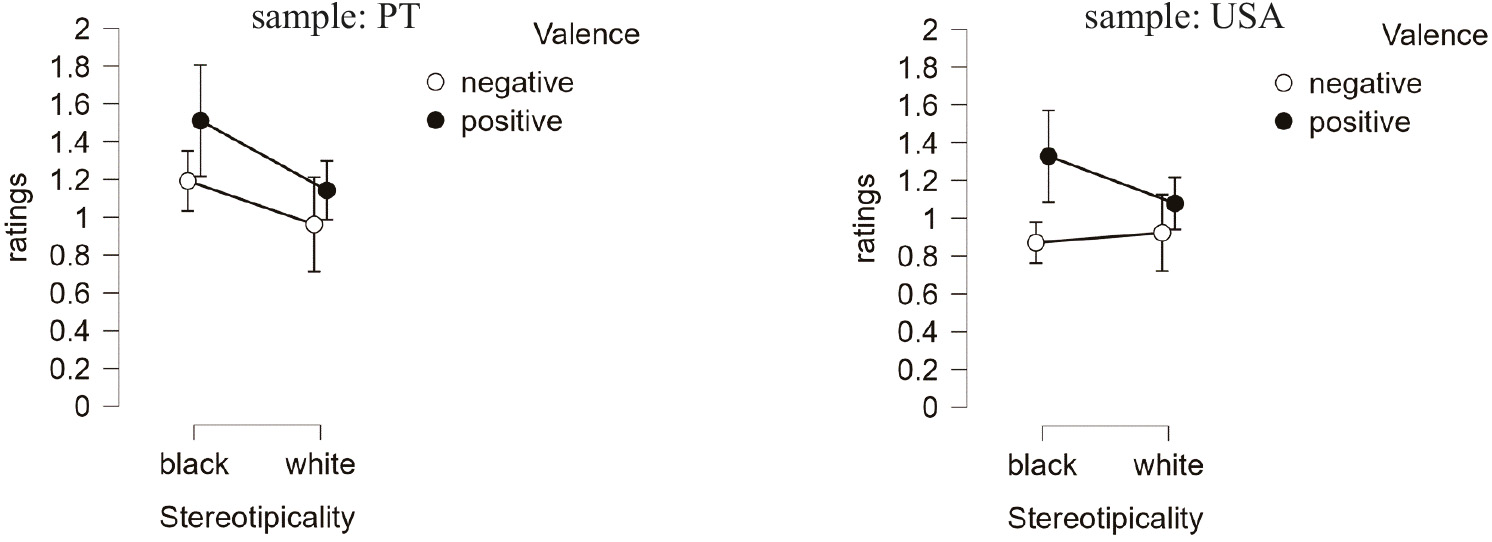

To examine whether the valence of the behaviors affected its perceived stereotypicality, we conducted a 2 (race: white, black) x 2 (valence: positive, negative) between-subjects ANOVA on the average judgments of stereotypicality. Note that in this analysis we used only the behaviors that were considered stereotypical of whites and blacks. This analysis revealed a main effect of valence, F(1,69)=13.55, p<.001, η 2 p =.164, where positive behaviors (M=1.20, SD=0.40) were judged as more stereotypical than negative behaviors (M=0.90, SD=0.27). The interaction between race and valence was not statistically significant, F(1,69)=3.30, p<.073, η 2 p =.046, as the remaining effects did not reach statistical significance. Although the graphical representation regarding the interaction (Figure 1) appears to suggest greater differences related to valence in the black behaviors (compared to whites), those differences are non-significant.

Experiment 2

The goal of Experiment 2 was to replicate Experiment 1 using a sample of Portuguese participants. Moreover, in this experiment, the stereotypicality and the valence judgments were performed by different participants and, therefore, are independent of each other, unlike the previous experiment.

Participants

The sample comprised 126 participants (103 females, 22 males and, one transgender; M age=24.1 years, SD age=9.7 years) recruited from the Faculty of Psychology (University of Lisbon) in exchange for course credits. Participation required participants to self-identify as Caucasian, which resulted in two exclusions.

Materials

We asked three independent judges, who were Portuguese native speakers, to translate and adapt to Portuguese the same set of behavioral descriptions used in the previous study. For every behavior in which there was no complete agreement, a consensus was reached by discussion among the research team.

Procedure

Again, participants signed up for a Qualtrics study named “Pre-test of behavioral descriptions”. After being informed that their participation was voluntary and that their responses were anonymous and confidential, participants gave their informed consent. Within the same questionnaire, participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions, in contrast to previous study in which all participants made stereotypical and valence judgments. Here, condition 1 (N=63) involved stereotypicality judgments while condition 2 (N=61) involved valence judgments. The task instructions were the same as the previous study, except that they were translated and adapted to Portuguese. As in the prior study, participants made their judgments on semantic differentials. In version 1, the anchors were as follows: 1 - “Extremely likely of Whites”, 5 - “Equally likely of Whites and Blacks”, and 9 - “Extremely likely of Blacks”. In version 2, the anchors were: 1 - “Extremely negative”, 5 - “Nor negative neither positive”, and 9 - “Extremely positive”.

Lastly, participants completed some socio-demographic questions (age, gender, race, and educational level), and were thanked and debriefed.

Results and discussion

As in the previous study, we assessed whether the average judgments for each behavioral description were significantly different from the middle point of the scale (i.e., 5). Stereotypical and valence judgments were independently tested and can be found in Appendix 1.

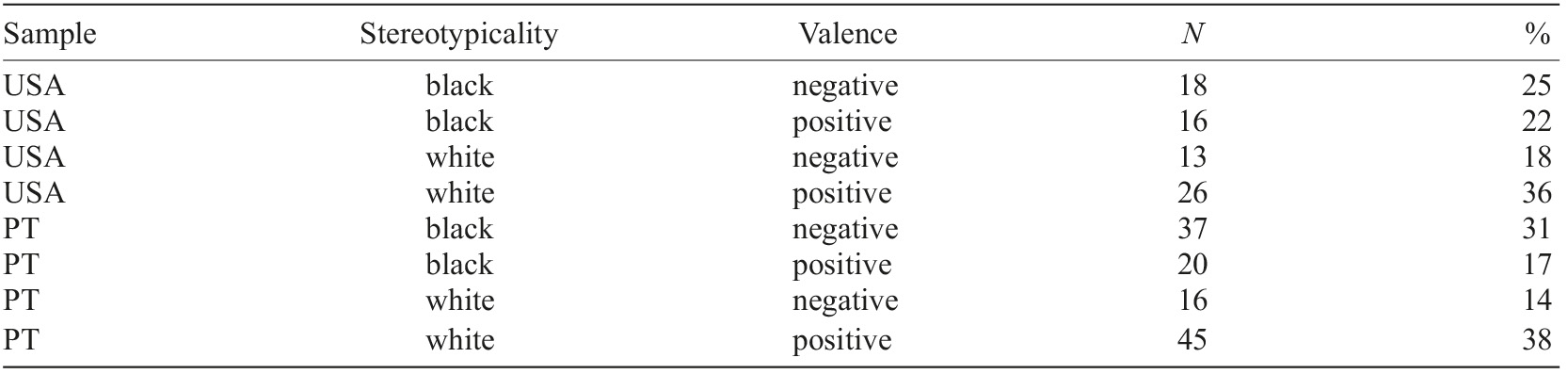

We follow the same behavior selection procedure as previously described. By checking Table 1, it is possible to conclude that behaviors were distributed as follows: 57 were stereotypical of black, and 61 were stereotypical of white. Within the stereotypical behaviors of black, 20 are positive (e.g., He cooked exotic gypsy food for his friends.) and 37 are negative (e.g., He said Africa is a country in the south of Spain.); while within the stereotypical behaviors of white 45 are positive (e.g., He enjoys spending time in the countryside.) and 16 are negative (e.g., He clearly has an attitude of superiority over others.). In addition to this, we obtained 23 neutral behaviors - eight positive (e.g., Although not very fond of pizza, he agreed to go.) and 15 negatives (e.g., He never listens to anyone.).

Table 1 Number (N) and percentage (%) of significant stereotypical (black vs. white) behavioral descriptions according to valence (positive vs. negative) between samples (United States of America, USA vs. Portugal, PT)

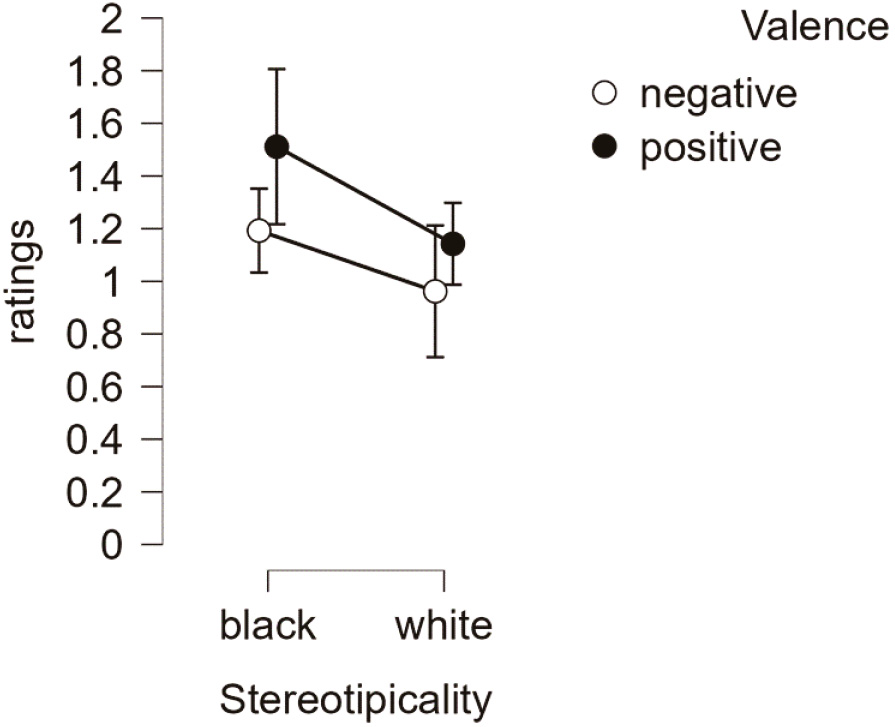

Once again, to study the role of valence on the average judgments of stereotypicality, we computed the dependent variable as described in Experiment 1. A 2 (race: white, black) x 2 (valence: positive, negative) between-subjects ANOVA on the average judgments of stereotypicality, as previously, revealed a main effect of race, F(1,114)=8.210, p<.005, η 2 p =.067, which means that behavioral descriptions of black (M=1.30, SD=0.55) are more stereotypical than behavioral descriptions of white (M=1.10, SD=0.51). We found a main effect of valence, F(1,114)=5.700, p<.019, η 2 p =.048, where positive behaviors (M=1.26, SD=0.58) are more stereotypical than negative behaviors (M=1.12, SD=0.48). The interaction did not reach significance (F<1, p=.509; Figure 2).

Comparison between samples

Finally, we compared the significant stereotypic evaluations, as before, between nationalities. To do so, on the average judgments of stereotypicality, we run a 2 (race: white, black) x 2 (valence: positive, negative) x 2 (sample: American vs. Portuguese) ANOVA, with race and valence as within-subjects and nationality as a between-subjects factor.

This analysis revealed a main effect of race, F(1,183)=7.55, p<.007, η 2 p =.04, where black-stereotypical behaviors (M=1.22, SD=0.51) were considered more stereotypical than white-stereotypical behaviors (M=1.07, SD=0.45). We found a main effect of valence, F(1,183)=14.67, p<.001, η 2 p =.07, with positive behaviors (M=1.22, SD=0.52) being judged as more stereotypical than negative behaviors (M=1.04, SD=0.43). And we also found a main effect of the sample, F(1,183)=4.38, p<.038, η 2 p =.02, which revealed that the Portuguese sample (M=1.20, SD=0.54) judged the behaviors as more stereotypical than the American sample (M=1.05, SD=0.38), as shown in Figure 3. Even though a visual inspection may suggest greater differences related to valence between stereotypical black behaviors than in the stereotypical white behaviors, that interaction as the remaining effects do not reach statistical significance (Fs<2.31 and ps>.131). Table 1 shows the distribution of behavioral descriptions according to the sample, stereotypicality, and valence.

Note. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3. Between samples comparison of the average judgments of stereotypicality according to valence

From the comparison of both studies, it also stands out that, in absolute values and disregarding valence, more stereotypical behaviors were obtained in the Portuguese sample (N=118) than in the American sample (N=73).

When comparing the percentage of common stereotypical behaviors, that is, when analyzing the percentage of behavioral descriptions judged in the same direction by both samples, we found differences. Of the 37 black negative stereotypical descriptions in the Portuguese sample, only 45,9% (N=17) obtained the same judgments in the American sample. When comparing the black positive stereotypical descriptions, from the 20 obtained in the Portuguese sample, 75% (N=15) were judged in the same way in the American sample. Through the comparison of white negative stereotypical behaviors, from the 16 found in the Portuguese sample, we found an agreement of 56,3% (N=9) by the American sample. And when comparing positive stereotypical white behaviors, from the 45 behaviors obtained in the Portuguese sample, the agreement in the American sample was 53,3% (N=24).

General discussion

The two main goals of this article were to pretest a set of behavioral descriptions regarding its racial stereotypicality and valence, in American and Portuguese samples, for future use in the Social Psychology field, and to examine whether these two samples have different perceptions regarding the same behavioral descriptions. The behavioral descriptions were rated both by American and Portuguese samples, and they varied in their stereotypical degree of white and black and also varied in valence. It should be noted that, despite the dissemination of the Afro-American stereotype in the literature, the present article aimed to develop stereotypical behavioral descriptions of black people and to compare both stereotypes. We presented 154 descriptions and asked participants to rate them in two semantic differentials: one related to valence, and the other to stereotypicality - whether the presented behavior was more likely of whites or blacks. Although there are some pre-tested behavioral descriptions in the literature, there’s a lack of quantity and diversity in racial descriptions, hence the need to fill this gap. And since this type of material is broadly used in Social Sciences research, namely, stereotypes, spontaneous trait inferences, impression formation, person memory, just to name a few, the goal was also to validate these descriptions for two distinct populations. In this regard, the sample of Study 1 was American, while the sample of Study 2 was Portuguese.

From the American sample data (Study 1), we obtained 34 stereotypical behavioral descriptions of blacks (16 positives and 18 negatives), 39 stereotypical behavioral descriptions of whites (26 positives and 13 negatives), and 52 neutral behavioral descriptions (19 positives and 33 negatives).

From the Portuguese sample, we obtained 57 stereotypical behavioral descriptions of blacks (20 positives and 37 negatives), 61 stereotypical behavioral descriptions of whites (45 positives and 16 negatives), and 23 neutral behavioral descriptions (eight positives and 15 negatives). All behavioral descriptions are available in the appendices section of this article.

When comparing the two studies regarding the number of stereotypic behaviors, it is quite clear that whites tend to be associated with a greater number of positive valenced behaviors while blacks tend to be more associated with negative valenced behaviors, which is consistent with previous research (Devine & Elliot, 1995; Falvello et al., 2015; Fazio et al., 1995; Livingston & Brewer, 2002). And when comparing the percentage of behavior that were judged similarly, in terms of stereotycality and valence, by both samples, the most pronounced differences can be found in the black negative stereotypical behaviors, thus supporting the claim of the existence of two different stereotypes (Afro-American vs. Black). Even though the similarities between the Afro-American and Black stereotypes, dissimilarities do exist. As Fiske (2017) stated race/ethnicity tend to be categories of social construction, thus permeable to the influence of historical and cultural events. The agreement of 75% of positive stereotypical behaviors of black between the American and Portuguese samples suggest a much higher consensus regarding the positive features related to the Black stereotype. However, it remains unknown whether this positive agreement is due to a higher awareness or familiarity of Blacks involved in politics, entertainment, and sports (Jewell, 1985) which in turn may influence positive black stereotypes. Or whether, we found support for Fiske’s (2017) warmth-competence space when she refers that black people tend to be moderately evaluated in this space, both by the Americans and Portugueses. Attending to the percentages of common agreement in the behavioral descriptions of whites, we are led to believe that there are also differences related to the white stereotype depending on the country where stereotypes are studied, which is not unexpected given differences in the historical, cultural, and social context (Fiske, 2017), between the United States of America (USA) and Portugal. A large body of research already revealed that a positive sense of national identity is pervasive in the United States (Citrin et al., 2001, p. 95) as the sense that the USA is a superior country compared with others. Still, would it be the case that the Portuguese sample in this specific study had stronger and more varied representations of the black stereotype? Would the American sample be more reticent to explicitly judge how stereotypical the behaviors were perceived? We would not predict old-fashioned racism, characterized for being blatant and obvious (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995; Ziegert & Hanges, 2005), and none of the behaviors obtained extreme judgments. However, being the modern racism more indirect, subtle, where people are capable of masking negative attitudes toward blacks (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995; Ziegert & Hanges, 2005), it is possible that we could not capture the most intimate or deeper personal perceptions from the American sample. Furthermore, other studies stereotypes-related have already noticed possible concerns regarding being rational (Miranda, 2014).

Although we had reached a set of behavioral sentences, stereotypical of blacks and whites, varying in its valence, for two samples, American and Portuguese, we find potential limitations of the present work. In Study 1, besides the sample being small, the sample is not independent, that is, although the order of valence and stereotype judgments was counterbalanced between participants, the same participants evaluated each behavioral description twice. Methodologically, despite the semantic differentials entailing several advantages (are closed-ended items, present a gradation of responses, Friborg et al., 2006; Furr, 2011), the inverted presentation of the semantic differentials, in half of the trials, would have been more correct to reduce the potential bias of the participants’ response. A more general constraint is related to the object of study: stereotypes. These types of studies raise issues of social desirability that are difficult to control and that lead to social disapproval (Kawakami et al., 2009; Tourangeau & Yan, 2007).

Despite these limitations, we reduced the literature gap concerning the stereotypical behavior descriptions, by providing a set of sentences perceived as stereotypical of white and black, varying in its stereotypical degree and in valence. Furthermore, this set of descriptions was validated using both, a Portuguese and also an American sample.