Introduction

The healthcare environment worldwide is becoming increasingly specialized, competitive, and cost-sensitive with a major focus on outcomes and value. This relies on real-world evidence (RWE) to complement epidemiological gaps and support decision-making 1. As such, RWE is growing in relevance 2,3 with a special focus on complementing data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Hence, RWE assesses the usage of health technologies outside of a controlled environment and in an applied setting with patients varying in co-morbidities and health conditions. This new era of RWE has the potential to generate a deeper understanding of the value of health technologies in real life 4,5.

Real-world data (RWD) entails routinely gathering information on a patient’s health status and delivery of healthcare procedures from sources other than traditional clinical trials. Data collected from patients is essential to generate RWE 6,7. Much of the data that RWD generates are from electronic health records, administrative and claims data, patient-generated data from websites and wearable sensors, measures of social determinants of health, environmental exposures, pharmacovigilance data, and patient registries 6. In contrast with electronic health records, where physicians in Portugal still register some data in unstructured text fields at a certain point of care, patient registries are databases that gather secondary data from patients that share certain characteristics, such as a particular disease, condition, or exposure risk. The data collected can be based on past (retrospectively) or future (prospectively) information. Patient registries also stand in sharp contrast to traditional observational studies, which tend to collect data for a limited period and on a restricted patient population. Therefore, patient registries are of particularly high value for evaluating the course of rare diseases and the effects of novel treatments 8 as they involve a long-term, systematic, and organized data collection approach, which is driven by specific and pre-defined aims 2,3.

Patient registries generally provide details on clinical outcomes and practice and may include patient-reported outcomes 9-12. RWE can be used to monitor health outcomes and treatment adherence. It can also be used to understand flaws, provide support to physicians in clinical practice, and analyse and possibly improve internal processes. This, in turn, can facilitate cost reduction in healthcare 9,12-19. Aside from complementing data from RCTs, patient registries can also support secondary studies in which research questions cannot be answered through other data sources. In addition, further research opportunities can arise when clinical data are complemented with other sources such as genomics, molecular biomarkers, and imaging information 9,20-25.

In Europe, some initiatives have been put in place to increase awareness of the use of RWD and enhance secondary data in the healthcare setting. The European Member States and the European Commission created a joint initiative, the Patient Registries Initiative (PARENT), to outline existing patient registries in the European Union and promote transparency and information sharing across countries 3. Several European countries, such as Italy (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco Registri - AIFA registry) and Spain (Sistema de Información para determinar el Valor Terapéutico en la Práctica Clínica Real de los Medicamentos de Alto Impacto Sanitario y Económico en el SNS - VALTERMED registry), are already implementing registries as support for healthcare decision-making. Specifically, VALTERMED is the corporate information system of the Spanish National Health System (NHS). It aims to determine the therapeutic value in real clinical practice of the drugs available in the NHS to enable adequate decision-making regarding their use at the different stages of the drug lifecycle based on the best available information 26.

Despite the importance and growing need for RWD and RWE, in Portugal, the current situation of patient registries is still not well known. Specifically, the representativeness, the attributes and quality of information collected, and the clinical areas already covered by patient registries are unclear 2. Knowing the current challenges for RWD in Portugal, some attempts have been made to improve patient registries such as the interactive tool (RegisPt) proposed by Laires et al. 2 To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive review of patient registries in Portugal has been conducted since then.

Hence, this study aimed to identify and provide a general overview of patient registries in Portugal to set a baseline for future developments in this domain. The scope of this search covers all patient registries that collect data from the Portuguese population.

Methods

A two-phase approach was used: a systematic literature review (SLR) using PRISMA© methodology, followed by an overview analysis of the patient registries identified during the research. This approach assumed that the existing registries would become published results, and as such, the selected information sources were accessible and classifiable.

Phase I - Registries Identification

Search Strategy

Studies containing data from Portugal were searched in the Embase®, MEDLINE©, and Cochrane© electronic databases using OVID® software. The search strategy included a set of registry-specific rules and search terms, in both Portuguese and English. The list of search terms used is provided in online supplementary File 1 (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000531447).

A set of inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined. Different types of databases, including patient registries, database studies, hospital studies, primary healthcare studies, and population-based studies gathering data from Portugal and published between January 1955 and March 2021, were included. Studies describing either a clinical registry or a database that gathers patient data on a procedure, disease, or healthcare resource and that collected data in a specific period or on an ongoing basis from the population being investigated were considered. Any setting and registry promotor, such as medical societies, health authorities, research centres, hospitals, and patients’ associations, were considered. Studies not including Portugal data (i.e., not including at least one Portuguese patient) were excluded. Additionally, RCTs and transversal observational studies (contrary to patient registry studies that collect longitudinal data) were excluded.

Study Selection

After being identified, the studies were reviewed and selected in two steps. Firstly, the titles and abstracts retrieved from the electronic databases were reviewed by two of the authors (H.P. and C.M.). Studies in which the title or abstract indicated patient registries collecting data from the Portuguese population were included in the next screening. Then, the full text of the studies that met the inclusion criteria in the first step was reviewed by the same two authors (H.P. and C.M.). A study was excluded if 1) it reported the intention to create a registry rather than an existing registry; 2) it did not include Portugal; and 3) it was an observational study rather than a registry. Any disagreements or lack of definite conclusions were resolved through discussion, and the remaining authors were consulted if the dispute persisted.

Identification of the Unique Registries

After identifying the eligible studies, the number of unique registries was assessed (as the same registry may be mentioned in more than one study). Not only was this step used to determine unique patient registries, but it was also used to evaluate the number of mentions in the literature.

Complementary Bibliographic Hand Searching

The electronic search was complemented with bibliographic hand searching using the Google® search engine. Hand searching was focused on the Portuguese terms: “registo * doentes.” This step allowed the identification of registries that possibly did not publish their results in indexed journals and, therefore, were not identified in the databases referred to above. The first 1,000 records (threshold considered without duplicate observations) were manually analysed to relate to patient registries in Portugal (e.g., analysis of data sources such as websites). A debate and analysis of the results were then conducted by the authors. A final list of unique patient registries in Portugal was generated by matching these results with those previously identified.

Phase II - Registries Overview

A search in publication and registry websites (when possible) was developed to provide a general overview of registries relevant to Portugal. Descriptive statistics were performed according to the following criteria:

Geography: “National,” if the registries were promoted by Portuguese entities and only collected data from the Portuguese population. “International,” if the registries were promoted by foreign entities and included sites in Portugal providing data on Portuguese patients.

Ownership: health authorities, research centres, patient associations, medical societies, hospitals, or the pharmaceutical industry.

Setting: hospitals, primary care, or directly from the community/population.

Medical speciality/disease: defined according to the classification of Colégio de Especialidade from Ordem dos Médicos 27.

Results

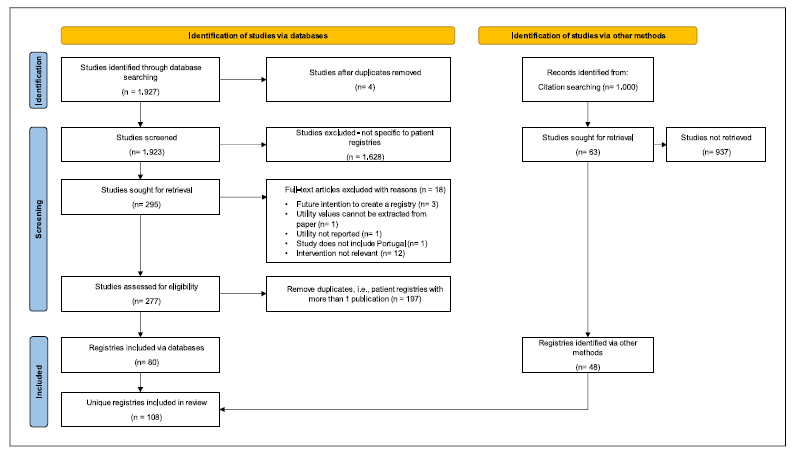

Using the search criteria defined in SLR, 1,927 relevant records mentioning registries were retrieved. From these, four were removed for being duplicates. A manual review screening of article titles and abstracts further removed 1,628 records that did not relate to patient registries. The full texts of the remaining 295 records were then analysed, and an additional 18 studies were excluded due to reasons explained in the study selection sub-section of Methodology. Finally, for the 277 suitable records, a manual review was performed to identify the unique patient registries. Overall, the SLR found 80 unique patient registries in Portugal. The complementary Google® search retrieved 48 registries. By combining the SLR and Google® search results, 108 unique registries were identified. The selection process to identify registries is summarized in Figure 1 and the list of the 108 registries can be found in online supplementary File 2.

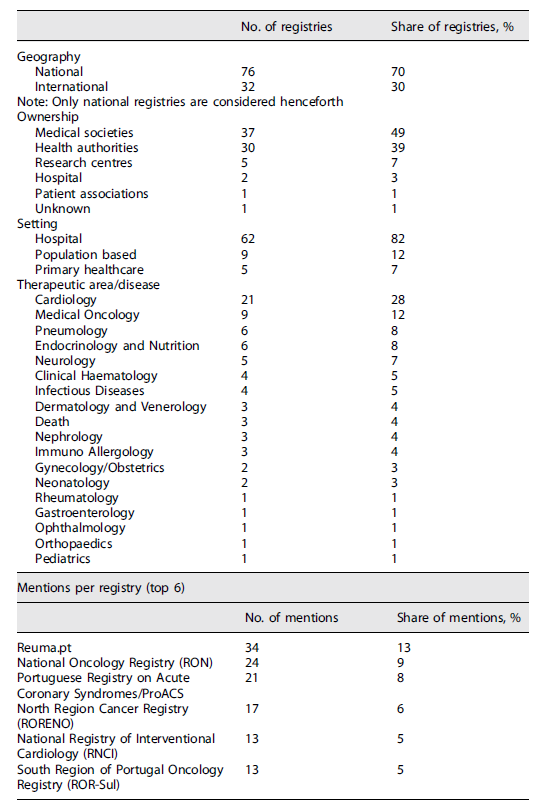

Concerning the number of mentions in the literature, Reuma.pt stands out as the highest documented registry with 34 publications. National Oncology Registry (RON) is next, covered in 24 papers, followed by the Portuguese Registry on Acute Coronary Syndromes/ProACS with 21 mentions in the literature. North Region Cancer Registry (RORENO) can be found in 17 publications, whereas the National Registry of Interventional Cardiology (RNCI) and South Region of Portugal Oncology Registry (ROR-Sul) both have 13 mentions.

Regarding geography, it was possible to verify that 76 registries (70% of the total) were local/national and the other 32 (30%) were international with representation of Portuguese sites. The vast majority were owned either by medical societies (49%) or health authorities (39%). Research centres owned 7% of the identified registries, while hospitals and patient associations held 3% and 1%, respectively.

In terms of implementation setting, most (82%) of patient registries were implemented in secondary care (hospitals). The remaining registries were population-based (12%) or applied in a primary healthcare setting (7%).

Registries covered 19 different medical specialities/diseases. Cardiology had the highest number of registries (21, i.e., 28%). Among these, the Portuguese Society of Cardiology was the major owner, managing 14 different patient registries. A relevant share of the identified registries covered the Medical Oncology domain (nine, i.e., 12%), with RON being responsible for five of these (data included regional registries before RON implementation). Some registries were specific to Pneumology (six, i.e., 8%). The remaining registries were managed by or concerned other specialities such as Endocrinology, Neurology, Haematology, and Dermatology, among others. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Discussion

In line with European initiatives, this study focused on the identification and overview of patient registries in Portugal to enrich the information available and promote the increased use of RWD at both national and international levels. Seventy-six national registries were identified out of the 108 unique registries assessed. The 32 registries classified as international provide national data to their data archives. This practice is regular in Europe since guidelines to standardize data collection exist to foster an environment where data can be benchmarked between different realities and practices.

Moreover, this study found that patient registries in Portugal have been mainly promoted by medical societies and health authorities. Medical societies play a major role in the definition of clinical guidelines and the development of clinical research. Developing RWE is crucial for the validation of clinical trials and benchmarking clinical practice for medical societies. Additionally, medical societies are in a unique position to obtain buy-in from different stakeholders, including physicians, which is essential for the implementation of a registry. By contrast, health authorities promote registries because they want to obtain epidemiological data, compare the quality of healthcare between institutions, evaluate policies, and support the evaluation of health technologies. RWD is necessary for these entities to define health policies based on evidence and develop assessments that will support adequate spending on healthcare. Overall, the results of the present study align with a priori expectations and corroborate what was previously mentioned in the literature 28,29.

This study also found that patient registries in Portugal are mainly implemented in hospitals. These results were expected because registries usually cover medical domains managed by speciality physicians, which typically follow patients in a hospital setting. Nonetheless, it would be interesting to assess the interest and capacity of the primary healthcare setting to implement more registries, particularly concerning diseases and/or conditions that affect a large proportion of the population and thus are followed in a different setting. For instance, metabolic and cardiovascular disorders (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, etc.) might be frequently found in primary healthcare facilities.

The use of patient registries has been increasing and varies according to the priority of the disease or medical condition under study 12. In terms of patient registry scope, the results of the present study showed that a significant share has been covered by the Cardiology and Oncology domains. These conditions have a significant incidence and contribution to mortality in Portugal, which in turn is reflected in a high economic impact and expenditure to manage these diseases 30,31. Furthermore, patient registries support analyses regarding drug effectiveness and therefore tend to support areas where health technology innovation is at the forefront. It should be noted that, despite the single registry related to Rheumatology, Reuma.pt (promoted by the Sociedade Portuguesa de Reumatologia) is the most widely mentioned. This is probably because this registry aggregates multiple conditions and diseases, whereas most other registries focus on a specific condition per registry (e.g., Cardiology). As such, Reuma.pt can work as a case study because centralizing all registries in the same pathology/therapeutic area may facilitate physicians’ buy-in while promoting synergies. Another factor that may contribute to the success of these registries (Cardiology, Oncology, and Rheumatology) is that they have resources specifically allocated to their management. On the flip side, research and medical areas like Infectious Diseases, Neurology, Psychiatry, Ophthalmology, and Dermatology have few or no registries in Portugal. Unlike Cardiology and Oncology, treatment in these medical areas may rely more on primary healthcare, which is more dispersed in the territory, thus hindering data collection and management. The number of patient registries per medical domain cannot be seen as the only measure of success. It would be interesting to understand if the success of the registries mentioned above is directly linked to physicians using them in clinical practice as a tool to support decision-making.

Most registries were identified from the SLR. The registries identified only through hand searching were not mentioned in scientific articles because such registries may not be yet active, be inactive, or belong to private entities that may not want to disclose results publicly.

In terms of limitations, it is worth mentioning that the SLR methodology has some disadvantages. These disadvantages include the fact that it can quickly become outdated, and its quality is heavily dependent on what has been published in the literature. As such, to keep an easy track of the different patient registries in Portugal, a centralized repository should be created in line with the several initiatives across Europe. Regarding the search strategy, we now realize that “randomized controlled trials” should not have been excluded. This strategy might have excluded articles that mentioned RCTs but may also contain information regarding patient registries. In addition, we should have considered including the term “epidemiological surveillance systems” in our searches. Finally, it should be mentioned that the present study only identified patient registries in Portugal, providing a general overview of each registry. In future work, the authors propose a comprehensive characterization of all the identified registries. This will allow understanding of how variables are collected, as well as validate the quality of the data being collected and checking whether the registries are still active.

Overall, the results revealed how disparate data collection remains in the healthcare sector even in. Although the results obtained are in line with previous findings, they also provide new insights into the development of patient registries in Portugal. However, a better understanding of patient registries will clarify their potential, usability, usefulness, and sustainability of collected data 2. To achieve such understanding, future projects should focus on providing a more detailed characterization of the patient registries identified to assess the quality and maintenance of data. This will promote transparency and, most importantly, the appropriate use of data, ultimately fostering more clinical studies in Portugal.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Julian Perelman and Dominik W. Schmid for their inputs throughout the study and for performing a final review of the manuscript. We also thank LisbonPH for supporting data analysis.

Statement of Ethics

This study uses publicly available data sources, and the authors have no contact with any data derived from the study of human participants.

Author Contributions

Hugo Pedrosa was responsible for study design, data collection, and manuscript drafting and review. Pedro Cruz provided insights as a subject expert and reviewed the final manuscript. Fábio Pereira managed data collection and reviewed the final manuscript. Magda Carrilho developed and reviewed the final manuscript. Catarina Martins supported data collection and data analysis and developed and reviewed the manuscript. Ricardo Martins developed the manuscript.