Introduction

According to the conceptual framework of the International Classification for Patient Safety of the World Health Organisation (WHO): “Safety is the reduction of risk of unnecessary harm to an acceptable minimum. An acceptable minimum refers to the collective notions of given current knowledge, resources available and the context in which care was delivered weighed against the risk of non-treatment or other treatment” [1, p. 154].

Health safety issues gained special attention and became a priority with the publication ofTo Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System[2]. This report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 2000, included the high number of deaths resulting from preventable clinical errors and the deficiencies of the systems that should prevent them. It was shown that health care system would be delayed by more than a decade when compared to other sectors that are considered to be a high risk for the safety of patients [2, p. 312].

Current available data show that many patients suffer errors each year and die due to the lack of safety associated with health care. According to the WHO, 1 in 10 patients are the victim of errors resulting from the care process, at least 50% of which are considered preventable [3,4, p. 18]. Of these errors, one-third cause mild to moderate harm and 5% cause serious harm [5]. Available evidence suggests that 134 million adverse events occurred annually due to the lack of safety in hospitals in underdeveloped and developing countries; this contributed to 2.6 million deaths in the same period [6, p. 8]. At the level of primary and outpatient health care, 1 in 4 patients is a victim of harm, and 80% of these cases could be avoided [7, p. 49]. These errors represent billions of Euros of harm to health systems worldwide, with 15% of hospital activity and funding being consumed as a result of complications resulting from errors in health care [8, p. 63].

At the national level, a study on Portuguese hospitals prepared in 2011 by the National School of Public Health obtained similar conclusions, i.e., an incidence rate of adverse events of approximately 11%, with 53% of the situations considered preventable [9, p. 36]. However, it has been verified that, despite continuous efforts to improve safety in hospitals, the harm caused by hospital care persists [10, 11, 12].

Among the strategies identified to promote safety is the recommendation to focus care on the patient, and to involve the patient and their family in the process [11,13, p. 11].

The recognition of patient-centered care as a fundamental strategy for quality came with the publication of a report by the Institute of Medicine:Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century[14]. Thus, with increasing recognition, the patient- and family-centered care (PFCC) model emerges as an asset for improving health outcomes in domains such as communication and patient satisfaction.

In 2005, the WHO created the Patients for Patient Safetyprogram. Its vision is to involve, empower, encourage, and facilitate patients and their families to build and/or participate in the health care process, by liasing with health professionals and policymakers to make health services safer, more integrated, and people-centered [13].

One of the key elements of the PFCC model is the adoption of an open and flexible policy with regard to hospital visits [15]. In fact, from an institutional point of view, in recent years there has been a growing openness by hospitals towards the family and greater attention to the humanization of health services [16]. Some health organizations recommend adopting an open visiting policy, with the aim of promoting the idea that patients and families can be true partners in care. They consider it an essential step in this change of culture that involves an openness to the presence of the family and their involvement in patient care [17].

The impact of the family presence on both patients and the health team and their organization is complex. Several studies demonstrate benefits for the patient, such as emotional support and a feeling of greater comfort in a hospital environment (which is characterized as being cold, sterile, and impersonal), a reduction in their anxiety, and the opportunity for the family to complement the care provided by health professionals [15,18,19]. It is also verified that family members who are present and involved in the health care provided are more prepared to assume care after discharge [20,21]. It has been observed that when health care administrators, caregivers, patients, and families work in partnership, the quality of health care increases, costs decrease, and patient satisfaction improves [11].

Despite this increase in satisfaction with these measures, the theoretical support that has been developed, and the institutional guidelines, the provision of care, particularly nursing, is still patient-centered and based on the biomedical model, with the family not seen as a target of care [12,22, p.123,23].

Although nurses recognize the importance of partnership with families, this is not always translated into the nursing practice [22]. Some professionals consider family visits to be a cause of potential risks and difficulties, an obstacle to care, a reason to fear increased workload, and a risk to care safety [17,24,25]. Overcrowded spaces are also pointed out as a consequence of the presence of the family that has an impact on the performance of health professionals [15]. There is reference to this presence demanding more from health care providers, increasing stress, and jeopardizing the well-being of these professionals [15].

In short, there is disparate information regarding the benefit of the presence of the family for the patient, and only scant information about the implications of this for the work processes of nurses. At issue are two clients, the patient and the family. What must also be addressed is what it implies for the safety of the patient when a nurse delegates some of their tasks to the patient or to the family.

Objectives

Considering that safety is of the utmost importance in the provision of health care, this review aimed to discover and understand the effects of the presence of family on a patient’s safety and hospital services as well as the implications, as a consequence, for the role of nurses.

Methods

The review process was based on the stages suggested by The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for scoping review [26], i.e., the definition of objectives, research questions, and inclusion and exclusion criteria; the planning of the research strategy and selection of studies; the specification of the method of data extraction; and the analysis, synthesis, and presentation of the knowledge produced.

We started with the following research question: What are the implications of the presence of family for the safety of the hospitalized patient? In the question formulated in this study, the PICO elements are: population (P) - patients; intervention (I) - presence of family; comparative (C) - absence of family; and outcome (O) - care safety (occurrence of adverse events).

Through the association of MeSH descriptors and free terms, a search of the Medline, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Scopus databases was carried out with the search expression: ([“family-centered care”] OR [famil*] OR [“visit*”]) AND ([safe*] OR [error] OR [“adverse event”]) AND [hospit*].

The research period ran from September 2019 to February 2020. Inclusion criteria were: studies that responded to our objective, i.e., having as research theme the effects of the presence of family on the safety of hospitalized patients conducted in the last 10 years (between January 2010 and January 2020), and quantitative, qualitative, and/or literature reviews in Portuguese, English, and Spanish.

The selection of studies was carried out initially from the titles and abstracts according to the inclusion criteria mentioned above. The selection was conducted by 2 independent reviewers, and disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer to confirm the eligibility of the studies. In cases of doubt, the full text was read. As this is an integrative review that follows the steps of a scoping review, no assessment of the methodological quality of the studies was carried out [26].

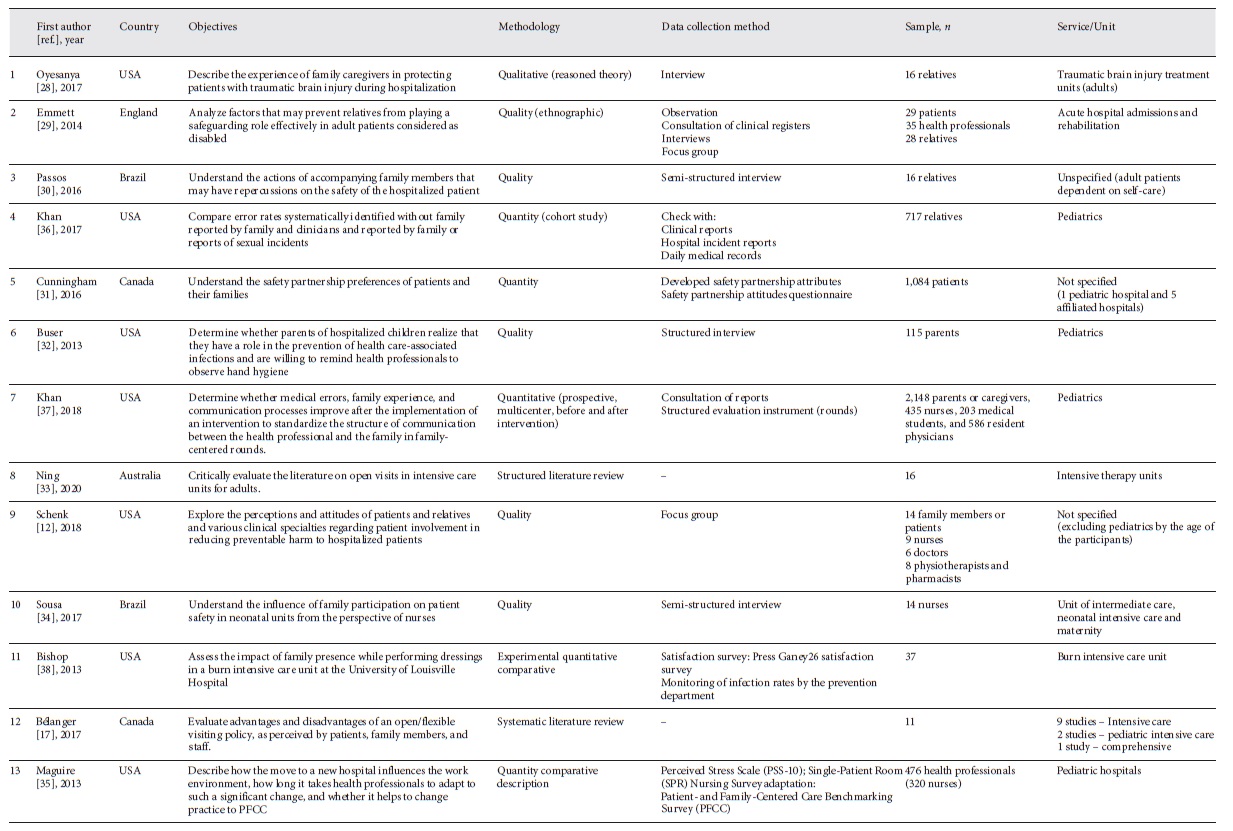

Research resulted in the identification of 115 studies. In the first phase, repeated articles were excluded. Subsequently, the articles were selected by analysis of the titles. Studies were then selected by analyzing the abstract and, finally, after reading the full article, by applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This process (Fig. 1) produced 13 articles: 6 qualitative studies, 5 quantitative studies, and 2 literature reviews.

Fig. 1 Selection process of the studies included in the review, adapted from PRISMA Diagram Flow [39].

Results

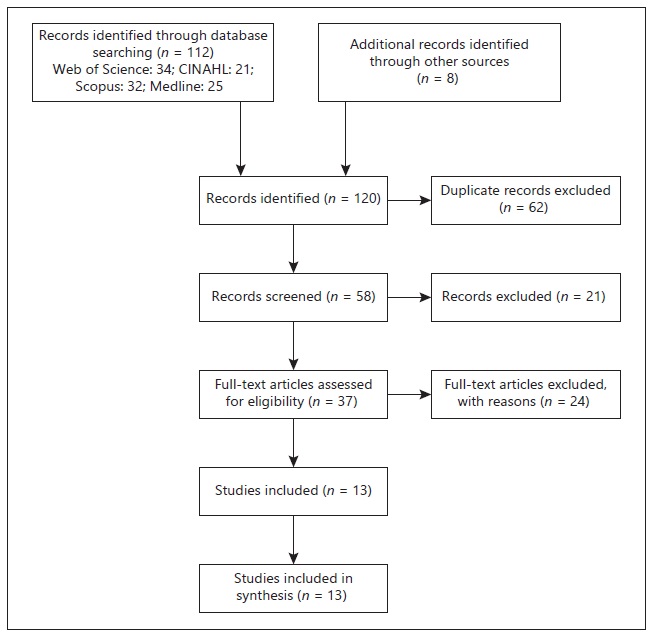

Thirty-three studies were selected according to the procedures described. The subsequent collection and systematization of the data were carried out using a summary table (Table 1), according to the JBI which descriptively presents the following data: authors and year, country of origin, objective, methodology, method of data extraction, and sample and service or unit where the studies were carried out [27]. This strategy/tool contributed to the identification of thematic categorizations.

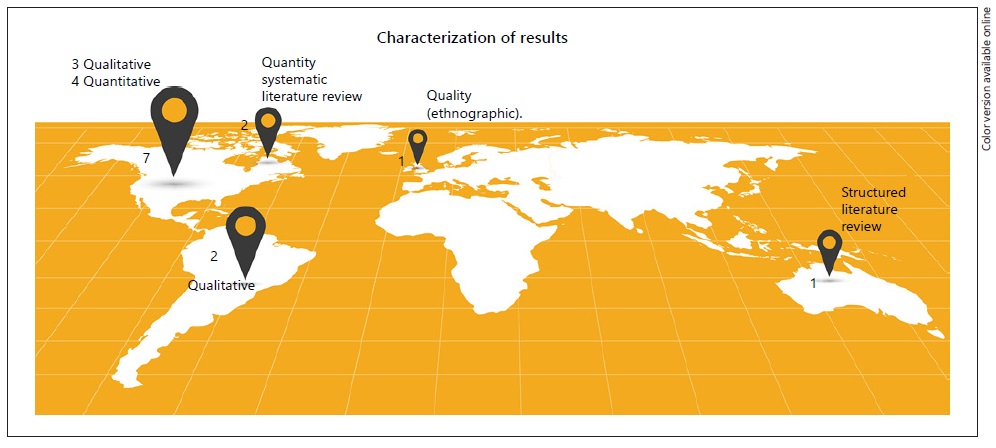

Of the 13 selected studies, 7 had their origin in the USA and 6 presented a qualitative methodology. These data may indicate that research in this area is still at an early stage of exploration. The higher production in the USA may indicate a greater commitment to the theme PFCC and thus greater investment in this research. To better understand the characteristics of the selected studies, we developed a graphic schema to demonstrate this distribution around the world (Fig. 2).

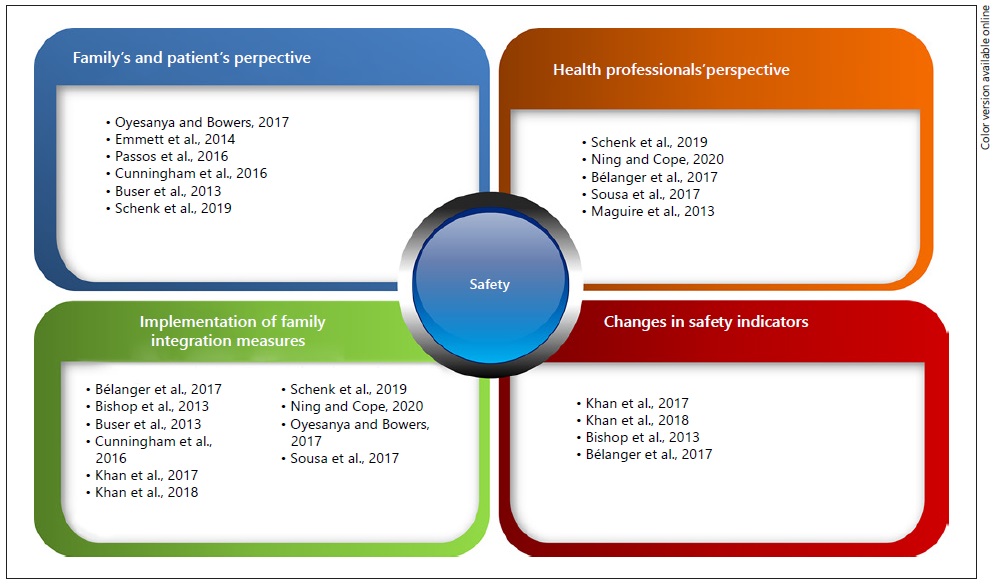

We presented the data available from these studies according to the source of information in each individual study, namely:

- the family and the patient;

- health professionals’ perspectives;

- statistical evidence (where data from quantitative studies are gathered with the aim of identifying if there are changes in safety indicators with the implementation of family integration measures in health care).

The perspective of patients and their families

The family’s perspective on its importance and role in health care safety is an important source of data that can help us understand the meanings, barriers, and reservations of these potential care partners to integrate these into safety for patients.

Some of the studies found that families care about the safety of their relatives and do make an effort. A study using interviews with 24 relatives of patients hospitalized for traumatic brain injury (TBI) reveals the nature of the involvement of these relatives and what strategies they developed to protect the patients from a physical and emotional point of view, specifically: influencing the selection of the health team, influencing the abandonment of bad habits on the part of the patient, anticipating the preparation of the home environment, establishing an emotional relationship with the patient, and managing the visits [28]. The study concluded that it is necessary to provide training to health professionals about the experience of family caregivers and the development of partnerships with them during hospitalization. Another qualitative study (ethnographic) was conducted, with the objective of analyzing whether family caregivers protect the interests of patients considered incapable, whether they dispute the decisions of health professionals when necessary, and what factors can prevent caregivers from performing this role effectively [29]. Once again, the results showed that family members strive to play a role in protecting and safeguarding the patients’ rights, taking into consideration that they were not qualified to do so. The authors identified a need for better sharing of information with families to safeguard patients’ rights.

Another study involving 16 relatives of hospitalized patients, with the objective of understanding the actions of family caregivers who may have an influence on the safety of hospitalized patients, concluded that relatives are concerned about patient safety issues and develop care actions for hospitalized patients [30]. Among these actions are the prevention of infections through waste separation, the hygiene of the environment, the use of gloves and hand-washing, the prevention of pressure ulcers, the administration of medication, feeding by gastric tube, and seeking to maintain a good relationship with the nursing team [30]. The authors found a lack of supervision and guidance on the part of the nursing team during the development of these actions, which puts the safety of the patient at risk as family members work on a basis of empirical knowledge.

In Canada, a study was conducted on 1,084 patients and family participants in various contexts of care, in order to understand the preferences of partnership for patient and family safety [31]. It concluded that family members prefer a safety model based on partnership with health professionals to a model that delegates responsibility for safety only to health professionals. They value the opportunity to actively participate in care safety, including the reverification of medication and reverifying the patient’s identity considering that they can provide a reduction of risks to care. Participants who were actively involved (73.3%) included people with a higher education, those more confident of their ability to contribute to safety, and those who valued more individual training strategies for safety and error disclosure. Passively involved participants (26.7%) were mainly those with less schooling, and hospitalized patients and their families less confident of their ability to contribute to safety and preferring a strategy based on signaling and guidance by health professionals. The authors concluded that health services should communicate information about risks to patients and family members, identify partnership preferences and create opportunities for these, respect individual differences, and present a positive response when patients and family members demonstrate concerns about health care safety [31].

Similarly, interviews of 115 parents of hospitalized children were conducted in a pediatric hospital in Philadelphia to determine whether they have a perception of the role they can play in preventing infections associated with health care and whether they are willing to remind health professionals of the need for hand-washing [32]. The study concluded that 84% of parents were aware of infections associated with health care, 78% considered hand hygiene the most important practice for the prevention of these infections, 67% would remind the health professional to do so, and 92% reported that the probability of doing this would increase if the health professionals invited them to do so. The parents showed interest in developing a partnership with the health professionals to prevent infections associated with the care of their hospitalized children, and the invitation to do this by health professionals has the potential to reduce perceived barriers and motivate the participation of patients and family members. However, despite the benefits pointed out, some concerns arose, such as the possibility that these partnerships would demand more from the health professionals, e.g., more of their time, and also the possibility that they experienced this supervision as “policing.” These reservations should be protected by structured and appropriate intervention strategies [32].

Another qualitative study which explored the perceptions and attitudes of patients, family members, nurses, physicians, pharmacists, and physiotherapists at 2 hospitals in the USA, in terms of the involvement of the patient and family in reducing preventable harm and safety risks in the hospital, stated that, for family members, the presence of the family increases safety, the active involvement of patients and families represents a significant opportunity to reduce risks and harm, and communication is essential but family members do not feel themselves heard [12]. The study concluded that the increased complexity of care increases the need for a partnership with patients and family members more intentionally to improve safety and that the involvement of the patient/family in reducing health errors offers potential solutions. Due to the lack of structured guidelines, participants in this research do not know how to develop these partnerships and end up developing contradictory activities when, actually, they all just want health care safety [12].

Health professionals’ perspectives

The study mentioned above covered not only families’ and patients’ perspectives but also those of the different health professionals, and came to the conclusion that the presence of the family increases safety in health care, and that the active involvement of patients and families can represent an opportunity to reduce risks and harm [12]. It also stated that this is nevertheless a challenge to execute and that in some situations there may be greater consumption of the health professionals’ time.

On the other hand, a review carried out with the objective of critically evaluating the literature, from 2013 to 2019, on open visiting policy in intensive care units identified barriers to the implementation of these measures that promote the integration of the family in health care, namely the perception of health professionals that such measures may jeopardize patient safety [33]. Health professionals identified health care disruptions as a consequence of open visiting measures and stated that these interruptions can jeopardize patient safety, especially if interventions are high risk. Increased patient exposure is also identified, including malicious visits and the risk of infection. It is reported that the presence of the family in interventions performed by professionals in training may compromise the family’s confidence in the care provided. It also pointed out the violation of the rights of patients who do not wish to be visited, or the constant presence of family members which can affect rest time, considered essential for the recovery of patients [33]. Another review on this subject revealed that health professionals see the presence of the family as an obstacle to providing care and that it causes an increase in their workload [17].

To understand the influence of family participation in the safety of patients in neonatal units from the perspective of nurses, a qualitative study was developed that involved 14 nurses in 2 Brazilian hospitals [34]. It revealed that nurses recognize the importance of the family for the safety of hospitalized patients and that the family should also be cared for. They also stated that they did not know how a patient’s family can specifically contribute to the prevention of adverse events, and they reported a lack of preparation for optimizing the involvement of the family in patient safety. However, they were able to list some strategies, namely welcoming the service as a fundamental moment for the integration of the family into the service. They also revealed that they perceive the family as a supervising agent and not as a partner, and that some family members are not well oriented and feel insecure which then jeopardizes the benefits of family presence.

Another study, conducted to understand how a move to a new hospital influenced the work environment, how long health professionals needed to adapt, and whether this move helped change the practice of PFCC, demonstrated that changes including individual room structures and family-centered care policies affected nurses and professionals with up to 3 years of experience. The most experienced professionals, therapists, nutritionists, pharmacists, and social workers were the most affected, with high levels of stress [35]. It was observed that having individual rooms for patients are very important for the patients and their families, but that this practice can actually increase nurses’ workload. One justification for individual rooms that pointed to the low level of stress of nurses, despite this increase in workload, was the increase in patient and family satisfaction and its impact on the interaction with nurses. As the study lasted 15 months, it would be expected that, despite an initial increase in stress, the bias would normalize over time with familiarity with the new realities. The authors reported that there were several factors that may have contributed to maintaining stress levels and more studies on this are needed.

Statistical Evidence

A quantitative study conducted on 989 hospitalized patients younger than 17 years and their families, with the objective of comparing error rates (systematically identified without the family and reported by the family), concluded that the family identified errors and adverse events that had not been identified otherwise or by others involved in health care, so that they represent potentially useful partners in the safety of hospitalized patients [36].

Another quantitative study on pediatric inpatient services at 7 hospitals aimed to determine whether medical errors, the family experience, and communication processes improved after the implementation of an intervention to standardize the structure of communication between the health professional and the family in family-centered “rounds.” Although this intervention was associated with a reduction in errors and adverse events, an an improvement in the experience of the family and communication processes, general errors did not actually change [37]. This intervention focused on structured communication, health literacy, family involvement, and bidirectional communication, and did not increase the time spent on rounds. However, the authors recommend further study on the effectiveness of this intervention, particularly in other contexts.

In the same line of research, an experimental study conducted to assess the impact of family presence during dressing application, in the burn intensive care unit at the University of Louisville Hospital, involved an approach to intervention that included the family, in which those who agreed to participate were informed about safety issues such as hand-washing and other instructions for the safety of all [38]. The first objective of this intervention was to improve communication and generate an opportunity for the literacy of these family members, the second was to prepare for discharge, and the last was to improve patient and family satisfaction with health care. The results showed a significant increase in the satisfaction with health care and a considerable decrease in the rate of infection associated with health care. However, there were other measures implemented in this unit from which no conclusions could be drawn, suggesting a need for further study [38]. Some barriers were identified, such as the resistance of the health team, which eventually surpassed itself, as well as the inadequate physical space to accommodate families during treatment.

The synthesis of evidence carried out in a literature review to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of a policy of open visiting, which is identified as one of the measures promoting the inclusion of families in health care, is congruent with the abovementioned study regarding infection rates. Both report that the increase in visiting hours is not related to an increased risk of infections associated with health care or septic complications in intensive care units, where most of the studies were conducted [17]. It also identified increased satisfaction with health care as an advantage of this measure [17].

To summarize the explanatory data, we present an analysis illustration (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Several international health organizations have made recommendations for the adoption of policies and practices that respect the model of PFCC, because they believe these can be partners in this process and thus contribute to the quality and safety of care. In this regard, some health institutions have implemented measures such as less restrictive visiting regulations.

There are only a few studies on the relationship between the involvement of family and the safety of hospitalized patients, and so it was necessary to opt for an integrative review that would allow for adding to and analyzing all the studies found in different specialties and with different methodologies.

The studies in this review describe arguments in favor of and others less favorable about this model of care provision. The evidence of greater patient and family satisfaction, lower levels of psychological distress for patients and family members, a greater sense of emotional support and a notion of better communication with health teams with less restrictive visiting hours were some of the favorable arguments [17,33,38].

The studies show that families are available and value the possibility of contributing to the care and safety of patients. However, it was observed that sometimes they are poorly informed, involved, and supervised [28-32]. The studies also reveal that health professionals believe that the involvement of family can enhance the quality and safety of care [12], and that there is no evidence that the flexibilization of visiting hours is related to higher in-hospital infection rates [17,38]. There is evidence that families identify errors and adverse events that are not reported otherwise or by others involved in health care, so they can be a very important source of information for safety [36].

On the other hand, health professionals tended to reveal that the involvement of family in the provision of health care may represent a challenging strategy and that, in some situations, it can be very time-consuming for professionals [12]. Regarding the implementation of greater flexibility of visits, limitations were pointed out by professionals, such as the fact that the free access to patients can affect rest time and patients’ recovery, disrupt the provision of health care, jeopardize patient safety, and violate a patient’s right to not want to be visited [17,33].

One of the studies described that professionals see the family as a supervisory element and not as partners [34]. In another study, there was an increase in the stress of health professionals with the implementation of measures that promoted family-centered care, but that the nurses were the least affected, and there were other variables involved that hindered conclusions [35].

Despite the least favorable arguments, 10 of the 13 studies made recommendations for family involvement in the provision of health care with the potential to contribute to patient safety, namely:

- The policy of flexibility of visits should be structured according to the nature of the service, the context, and the characteristics of the patients. it should also respect the patient’s right to decide on his or her visits according to his/her preferences and needs [17].

- Similarly, partnerships should be established with the patient and family, and their preferences and needs must be respected [12,31,34].

- With family involvement, it is important to teach the skills necessary to participate and also improve self-efficacy in the level of patient safety, such as teaching the technique of hand hygiene [31,32]. This and other safety information should be available on the institute’s website or provided to the patient and family [17].

- The family should be included in the safety surveillance of the hospitalized patient, in particular with regard to the notification of adverse and other events [36].

- Promoting the involvement of family in rounds demonstrates the potential to improve care safety without impacting on the duration of the same [37].

- Training of health professionals on the family-centered care model [28].

Conclusion

The available evidence gathered in this review shows that patients’ families are making efforts to ensure patient safety. Some of these efforts are in line with the recommendations for the prevention of risk of infection, among other safety recommendations. However, families feel unprepared and report a lack of follow-up by health professionals to collaborate at this level.

Several studies pointed to the need to improve communication between health professionals and families, namely regarding health care safety issues. Health professionals have differing opinions. Some identify, as do family members, that the involvement of family in the safety of the hospitalized patient represents an added value. Others, however, in view of more concrete measures like extending visiting hours, claim that patient safety is at risk and that this measure does not protect them. They see the family as a supervisory element, and fear an increase in the workload; nevertheless, this has not increased the stress level of nurses.

A study conducted in Brazil showed that nurses regularly delegate health care to family members, who are ill-prepared to perform them without supervision, and that this may pose risks for patient safety [30]. More structured family involvement initiatives seem to have positive results in care safety. In this sense, it is important that measures of involvement and family-centered care are structured.

Among the measures for implementing family-centered care are:

- the implementation of an open visiting policy;

- the integration of families in processes of notification of adverse events;

- the integration of families in rounds or at specific times of health care that promote improvement in results;

- the improvement of the process of communication between families and health professionals;

- the provision of information and teaching family members about care safety.

However, it is verified that the involvement of patient and family in health care safety issues and their relationship with harm reduction is not well understood, and findings in the current literature are limited. Quantitative studies on this topic and carried out in health care services, other than Pediatrics and Intensive Care, are scarce. Thus, more quantitative studies and in different specialties are necessary in order to promote interventions with the greatest possible safety during a hospital stay, respecting the humanization of health care to the hospitalized person, whenever possible integrating his/her family. Similarly, it would be important to develop studies of this nature in Portugal, given the importance of the evidence of the involvement of family in health care safety in this country.

Relevance for clinical practice

PFCC is of special importance for the clinical practice of nurses and other health professionals and should always be present in the practice of care. In addition to this recommendation, there is a need to ensure patient safety, and therefore implement strategies into health services that promote a balance between these two health demands. The evidence found on the relationship between family involvement and the safety of hospitalized patients is limited. However, more structured family involvement strategies seem to show positive results for patient safety. These strategies must respect the principle of PFCC, which must be included in the patient safety process via a partnership established by and with health professionals.

Further studies on possible models or programs that reconcile the demands mentioned here are necessary.

Funding sources

The authors declare that there was no financial or material support, so no funding sources, for the development of the research or work that resulted in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author contributions

T.S.P.C.: design and conception on the relationship between the involvement of family and the safety of the hospitalized patients of the work; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the work; accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved.

M.M.F.P.S.M. and F.F.M.B.: substantial contributions to the design and conception of the work; important contributions to the selection, analysis and interpretation of data for the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.