Introduction

Nitrofurantoin is a well-recognized drug with multiple adverse reactions. However, concomitant lung and hepatotoxicity is uncommon and has been reported in 10-18% of nitrofurantoin-associated hepatotoxicity series [2]. Nitrofurantoin-induced autoimmune hepatitis has a female predominance (85.5%), with 38.5% of cases occurring in elderly patients (>65 years) [1], and age is a particular risk factor for liver injury in chronic forms [3]. Liver biochemistry tests suggesting hepatocellular injury are the most frequent alterations (67-71%), but occasional cholestasis may be present [3,4]. Liver biopsy often shows a pattern of chronic active hepatitis. In chronic cases, nuclear antibodies (80-82%), smooth muscle antibodies (55-73%), and lupus erythematosus cells (50%) were frequently presented [1,5]. The authors present an uncommon and concomitant adverse reaction with a common drug.

Case Presentation

A 68-year-old immigrant Iranian woman was treated with nitrofurantoin 100 mg once daily for urinary tract infection prophylaxis from January 2017 to June 2019. In September 2019, after suspicion of urinary tract infection, she restarted nitrofurantoin at the same dose. From November to March 2020, she presented progressive exercise dyspnea, fatigue, member cramps, and irritating nocturnal cough. She started amoxicillin, clavulanic acid, and clarithromycin for a diagnosis of respiratory infection, without response. In April 2020, she began experiencing involuntary weight loss (7%), stopped statin, and started taking a red rice pill once a day. In June 2020, painless jaundice, mild itchiness, dark brown urine, and fecal acholia for the previous 3 weeks led to an internal medicine ward admission for additional investigation. Ten days prior to admission, amoxicillin and clarithromycin were prescribed afterHelicobacter pyloriidentification. Some other courses of antibiotic and anti-inflammatory drugs were prescribed since 2017 (Fig.1). Her medical records disclosed dyslipidemia and surgical hypothyroidism. There was no history of liver disease or alcohol or drug consumption. Physical examination showed an afebrile and normal-weight patient with sclerotic jaundice, pulmonary bilateral and inferior fine inspiratory crackles, normal peripheral rest oxygen saturation, and no abdominal portosystemic circulation, organomegaly, masses, pain, or ascites. Her cardiac and cutaneous examination was unremarkable and she had no encephalopathy, edema, or adenopathies. At this moment, after a high clinical suspicion, nitrofurantoin, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin were stopped.

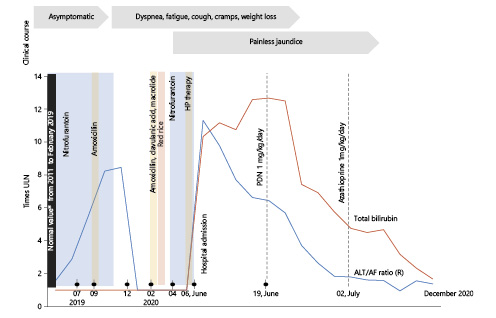

Fig. 1 Clinical course and timeline of nitrofurantoin intake and their relationship with liver enzymes alterations in ALT ULN/AF ULN ratio and total bilirubin (times ULN). *Normal values included liver function and enzymes, but also antinuclear antibodies and IgG evaluated in 2016. HP,Helicobacter pyloritherapy (amoxicillin and macrolide); ULN, upper limit of normal.

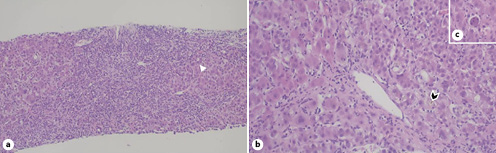

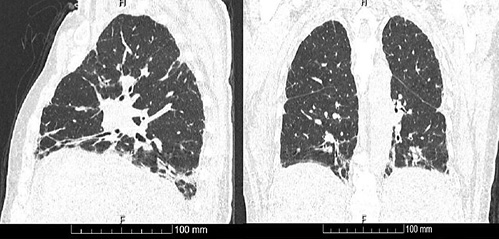

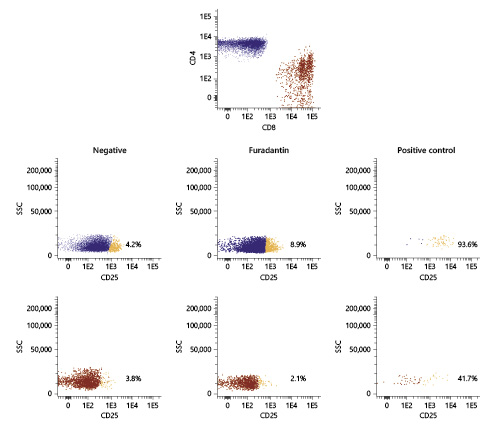

Blood analysis disclosed hepatocellular liver injury (ALT/ALP ratio 11.3), hyperbilirubinemia (10.25 upper limit of normal), hypoalbuminemia (minimum 2.1 g/L), and slightly lower prothrombin (53%) with normal factor V and platelet values. ProBNP was normal. Severe vitamin D deficiency with secondary hyperparathyroidism was diagnosed, without vitamin B12 or B9 deficiency. Her ferritin value was 600 ng/mL (normal 30-300), with increased transferrin saturation (91%) but no detection of H63D, S65C, or C282Y HFE mutations. Electrophoresis showed gamma fraction polyclonal peak with IgG 35.79 g/L (normal 5.52-16.31). Seric autoimmunity unveiled a homogeneous pattern (AC1) antinuclear antibody titer of 1/640, but presence of other antibodies such as anti-ds-DNA, anti-histones, anti-SSA60, SSB, Sm, RNP, Scl70, JO1, anti-mitochondrial, pyruvate, anti-LKM, SLA/LP, LC-1, and smooth muscle antibodies was excluded. Until 2017, liver enzymes and autoimmunity panel were unremarkable. Acute or chronic viral hepatitis (A, B, C, and E) and other hepatotropic viruses (cytomegalovirus, herpesvirus, and Epstein-Barr virus) were also ruled out. Similarly, metabolic liver conditions were assessed, including alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, and hemochromatosis. Lower limb electromyogram was normal. Biochemical urinalysis, cytological examination, as well as bladder and kidney imaging did not show any alterations. Abdominal CT disclosed lobulated and heterogeneous liver tissue and a mild perihepatic effusion, without bile obstruction or expansive process. Liver biopsy (Fig. 2) supported the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis with typical autoimmune features: portal tract moderate mononuclear cell inflammatory infiltrate, with mild plasmacytes and some eosinophils, severe interface hepatitis with focal emperipolesis, periportal hepatocellular rosetting and ballooning, and ductular reaction. Severe panlobular bilirubinostasis, focal lobular necroinflammatory activity, and mild to moderate portal fibrosis (Masson trichrome) were also observed as well as focal periportal copper deposit (rhodamine). Biliary lesions, steatosis, iron deposit (Perl’s) and hyaline inclusions (PAS-D) were absent. High-resolution chest CT (Fig. 3) supported a previous radiologic hypothesis: bilateral inferior fibrosis. Despite a normal respiratory function test in December, a repeat evaluation in June disclosed moderate restrictive lung disease with mild reduced carbon monoxide diffusion. In bronchial fibroscopy, macrophage predominance, a low CD4/8 ratio, and unspecific lymph-hystiocitary inflammatory cells was observed, without neoplasia or infectious evidence (Pneumocystis jirovecii, bacteria,Mycobacteria, fungus, and cytomegalovirus). Echocardiography and electrocardiography were normal. In vitro lymphocyte transformation test disclosed, in the presence of nitrofurantoin, a mild increase in TCD4 cells expressing CD25 (IL-2 receptor α-subunit).

Fig. 2 Liver biopsy.aChronic hepatitis pattern of injury with portal-based fibrosis and dense inflammatory cell infiltrates composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells with severe periportal interface activity, hepatocyte rosettes (arrowhead), ductular reaction, and focal emperipolesis. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×100.bPerivenular necroinflammatory activity with prominent mononuclear inflammation and bilirubinostasis with bile plugging of dilated canaliculi (arrowhead). Hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200.cAcidophil body (individual necrotic hepatocyte). Hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200.

Fig. 3 High-resolution chest CT at hospital admission with bilateral fibrosis on the pulmonary basis.

Considering the histological evidence and progressive liver dysfunction, prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day and calcium plus vitamin D supplementation were initiated. Corticoid therapy was complicated by hyperglycemia and cushingoid appearance. Therefore, the patient initiated azathioprine with further dose titration and prednisolone was tapered. Her thiopurine methyltransferase genotype was 1*1*, compatible with normal enzyme activity. After 6 months, the patient presented good tolerance to azathioprine, had no fatigue or cramps, and showed improved dyspnea although interstitial lung fibrosis persisted in follow-up chest CT. Figure summarizes the clinical and analytical evolution with normalization of ALT/AF ratio, total bilirubin, and liver function. IgG also reached normal values. According to the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale, this case fulfills definite causality for nitrofurantoin-associated liver toxicity.

Discussion and Conclusion

We present a case of definite causality of nitrofurantoin with autoimmune-like hepatitis, concurrent with interstitial lung disease. This is an uncommon combination of nitrofurantoin toxicity only described in a few publications and present in 10-18% of nitrofurantoin-associated hepatotoxicity series [1].

The Netherlands Centre for Monitoring of Adverse Reactions to Drugs stated that in 261 autoimmune hepatitis cases from 1963 to 1988 [4,6], 24 (9.2%) were suspected to be drug-induced and >90% due to nitrofurantoin or minocycline-induced. Antibiotics were common hepatotoxicity-associated drugs following cytostatic and immunomodulatory therapy (17%) in a Portuguese database [4,7]. According to European data, EudraVigilance [2], from a total of 7,868 cases of nitrofurantoin adverse reactions, where 0.8% were Portuguese reports, 740 (9.4%) had hepatobiliary disorders, which included autoimmune hepatitis in 78. However, most reactions were reported as acute or chronic unspecified liver injury, and therefore the underlying liver injury data are limited [2]. Further, potential concomitant toxins sometimes hamper a definitive relationship between drug and injury.

In our case, clarithromycin was a potential liver toxic, but it faults in temporal relation and typical liver injury pattern, which usually appears within the first 1-3 weeks and with a cholestatic hepatitis pattern [3]. Nitrofurantoin-induced autoimmune hepatitis seems to have a female predominance (86-100%) [6], and 38.5% occur in elderly (patients >65 years) [2], with age acting as a possible risk factor for liver injury in chronic forms [3]. Liver biochemistry suggested hepatocellular injury pattern as the most frequent (67-71%), with occasional cholestasis [4, 6]. In chronic cases, nuclear antibodies (80-82%), smooth muscle antibodies (55-73%), and lupus erythematosus cells (50%) were frequently present [5, 6, 8]. It is believed that a breakdown product or nitrofurantoin itself that has been presented to class I HLA complex activates cytotoxic T cells, this with a pathogenic role in drug-induced liver injury [9]. On the other hand, nitrofurantoin-induced lung injury was reported in 28.5%, one-third with pulmonary fibrosis or interstitial lung disease [2], and the reason why nitrofurantoin affects the lungs remains unclear, but the ability to generate oxygen radicals and to cause lung injury seems to be one mechanism [10]. In our case a lymphocyte transformation test (Fig. 4) was additionally done but, nowadays, it does not have a definite role in the diagnosis of drug-induced lung disease [11] or in liver injury where data were not reproducible, except for isoniazid-associated liver injury [12].

Fig. 4 Modified lymphocyte transformation test based on CD25 (intermediate activation) for lymphocyte activation evaluation disclosing a mild increase in TCD4 cells expressing CD25 (IL-2 receptor α-subunit) in the presence of nitrofurantoin.

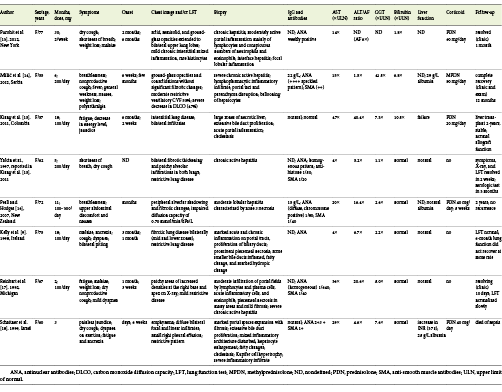

We selected PubMed Central database articles focusing on published cases of concomitant nitrofurantoin-induced lung and liver disease, including adults with a pulmonary evaluation and liver biopsy (Table 1) [9,13-18]. Data showed elderly women with prolonged nitrofurantoin use, where fatigue and respiratory symptoms (as dyspnea and dry cough) precede jaundice for weeks to months. Mild to moderate restrictive lung pattern with reduced diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide was frequent. As mentioned above, similar hepatocellular injury and serological profile were identified. Clinical and analytical recovery occurs in almost all patients after 1-2 months after drug withdrawal, but pulmonary dysfunction may persist. However, and after data revision, possible confounders may exist: undiagnosed or unreported concomitant organ toxicity, difficulty in establishing a definitive relationship between drug and toxicity, potential simultaneous toxic drugs, and a lack of medical practice in reporting drug reaction. The article highlights an uncommon concomitant liver and lung toxicity due to a common drug but with unspecified and unrecognized symptoms causing a delay in diagnosis.

Table 1 Selected PubMed Central database articles focusing on concomitant nitrofurantoin-induced lung and autoimmune hepatitis; adults with pulmonary evaluation and liver biopsy were included [9,13-18]

Learning Points

(1) Concomitant lung fibrosis and nitrofurantoin-induced autoimmune hepatitis is not commonly reported. (2) It is more frequent in elderly women with prolonged nitrofurantoin intake and respiratory symptoms preceding jaundice for weeks to months. (3) Restrictive lung pattern, hepatocellular injury, as well as nuclear and smooth muscle antibodies are frequent findings.