1. Introduction

“Patient safety” needs to be discussed responsibly and is indispensable in training future professionals to prevent adverse events and develop a patient safety culture (Wegner et al., 2016).

The World Health Organization (WHO) refers to patient safety in the International Classification of Patient Safety as the reduction of risk of unnecessary harm associated with healthcare to an acceptable minimum, which refers to the collective notions of current knowledge, such as an error related to non-treatment, ineffective or incorrect implementation of a care strategy or adverse events (Siman & Brito, 2016).

The principle of “first, do no harm” permeates patient safety worldwide as a significant challenge for organizations. In health care, risks are linked to work processes, whereby a high incidence of complications may result in prolonged hospitalization times, irreversible sequelae and even death (Reis et al., 2017).

It is essential to measure quality indicators (rate of falls, hospital infection, wrong-site surgeries, hand-washing frequency, laterality errors, pressure ulcers, and medication errors), since they reflect safety practices, in addition to being referenced globally and monitored in all institutions that adhere to the protocols (Silva et al., 2018).

According to National Curriculum Guidelines, nurses should receive generalist, humanistic, critical and reflexive training, based on scientific and intellectual rigor. This is grounded on ethical principles that allow health services to implement measures that guarantee the healthcare provided by nurses, as well as measuring and assessing the impact of its outcomes (Siqueira et al., 2019).

With a view to providing greater safety, the Commission to Implement the National Patient Safety Program (CIPNSP) was instituted to create the following protocols: correct patient identification; effective communication; safe drug administration, including high-surveillance drugs; safe surgeries; less risk of care-related infection; prevention of fall-related injuries; prevention of pressure ulcers; safe equipment and material use; and safe patient transfer (Siman & Brito, 2016).

The National Patient Safety Program (PNSP) of 2013 was instituted by Ordinance 529, which established the measures and goals (Ministério da Saúde, 2013). In the same year, Directory Collegiate Resolution 36 stipulated the mandatory implementation of a Patient Safety Center (NSP) in hospitals, aimed at reducing the occurrence of injury and adverse events, improving service quality, and promoting and enhancing the quality of patient records (Serra et al., 2016).

However, despite Brazil’s commitment to developing practical public health practices aimed at public safety, there is still a high incidence of adverse events in hospitals (Siman & Brito, 2016).

According to Azevedo et al. (2016), nurses are front-line healthcare providers since they deal directly with patients and are, therefore, more susceptible to causing adverse events because, among their numerous activities, they frequently perform invasive procedures.

There are few studies involving students in the topic under study in terms of implementing a “Patient safety” discipline in the curriculum from the onset of the course or as a theoretical framework.

In general, technical, structural, human, and process flaws can be predicted, which, taken together, can compromise patient safety. Thus, the present study aims to answer the following research question: how do undergraduate nursing students perceive patients as an integral part of the teaching-learning process?

A qualitative case study was used to analyze students’ perceptions of patient safety during the undergraduate nursing course at an institution of higher learning.

2. Methodology

This is an exploratory single-case study with a qualitative approach. The case under study is patient safety from the perspective of nursing students.

Case studies are widely used in education for their simplicity and specificity. This type of study is unique because, despite the similarities or differences compared to other studies, it can provide significant contributions in describing a real case (Ludke & André, 2020).

There is a consensus among some authors that case studies are qualitative in nature, but this is not the rule. Qualitative research is a complete, detailed, and contextualized description of the facts, providing a framework for what is contained in the studies (Ludke & André, 2020).

According to Minayo (2010), this approach allows a greater understanding of participants’ (individuals or small groups) perception of the phenomena that surround them, thereby deepening their experiences, identifying little-known social processes of certain groups, and, most importantly, devising new approaches and strategies.

The scenario of the present study is the ASCES-UNITA University Nursing Course in the city of Caruaru, in Northeastern Brazil. Five researchers took part in this study.

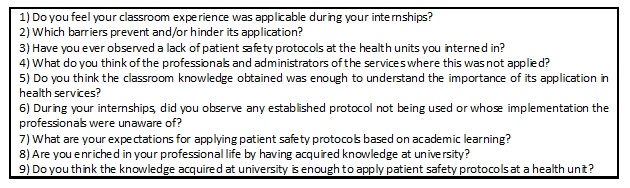

The participants were selected intentionally from all the students enrolled in the final semester of the nursing course. To preserve their identity, students used random numbers to be identified in the study (for example, STUDENT28). In March 2022, data were collected in an online focus group (OFG) of 12 students.

An OFG is an information collection method that resembles its in-person counterpart. Its main characteristic is the social distancing between participants since interactions occur virtually, synchronously, or asynchronously, using discussion groups and email exchanges and allowing participants to read comments and contribute at any time (Duarte et al., 2015).

In the present study, the OFG occurred via Google Meet and consisted of the moderator, observer, and researcher. The moderator intermediated and coordinated the OFG, facilitating interaction between the members. The observer, who also provided audiovisual resources, helped the moderator observe the main student’s verbal and nonverbal expressions. A written informed consent form was made available to students on Google Forms.

The data obtained for a total of 12 students from the guiding questions were processed in NVivo, version 12.0. The results are presented in word and tree clouds according to the frequency of the categories used (Figure 1).

The research project was approved by the UFAL Research Ethics Committee under protocol number 42241220.0.0000.5013.

3. Results and discussion

A total of 12 students (eight women and four men) took part in the study. The participants were a homogeneous group in terms of knowledge of the topic, albeit with widely varying ages, predominantly between 21 and 25 years (75%), followed by 26 to 30 (16.7%) and 31 to 35 (8.3%) and a majority were women (66.7%).

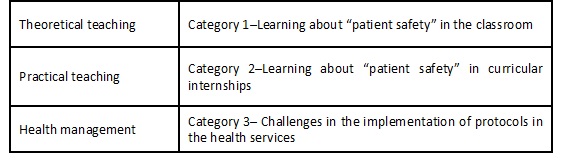

In the present study, data based on the nursing students’ statements reflected the theoretical teaching focus in the classroom, in practice via the curricular internships and health management from which the categories emerged (Figure 2)..

The data processed in the NVivo software formed a word tree that culminated in the three categories discussed below.

3.1 Category 1: Learning about “patient safety” in the classroom

The nursing students’ statements reflect theoretical teaching about patient safety at the institution. Most students agree that although the topic is included in a disassociated manner when compared to other disciplines, it is taught satisfactorily and contextualized in practice.

In general, patient safety content was addressed gradually in all the thematic units (STUDENT13).

We have been exposed from the first module until now; we learn about the care that Florence Nightingale took and everything from simple hand washing to preoperative care (STUDENT1).

We have no specific patient safety discipline, but we learn about it in the undergraduate course from different professors, little by little (STUDENT28).

However, it is important to note that when organizing teaching according to National Patient Safety Program (PNSP) guidelines, the topic should be incorporated into the theoretical framework and into a methodology that in practice, may lead to teaching-learning measures (Siqueira et al., 2019).

In the present study, we could not access the Pedagogic Political Plan (PPP) of the nursing course to determine the theoretical framework of “patient safety” in relation to the disciplines of the curriculum matrix. According to Siqueira et al. (2019), when the Institution of Higher Learning (IHL) does not offer a specific course on this topic, patient safety is taught in a fragmented way, and its specificities are poorly valued, demonstrating a series of deficiencies in its theoretical content base. A more in-depth study should be conducted to investigate the concept, principles, and philosophy of patient safety in academic training.

Some studies, such as that of Cauduro et al. (2017) at the Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM) in Brazil, demonstrate that although the students perceived patient safety teaching favorably, the topic is presented indirectly, and learning occurs individually, not contextualized or via shared experiences with other professionals.

Danko (2019) conducted a study with 44 nursing students enrolled in a perioperative course with four assessment levels: reaction, learning, behavior, and results. The author showed the importance of obtaining technical data from the students to inform professors about the patient safety knowledge acquired and explore additional learning using a dynamic approach in search of positive results. It is important to note that this experience can be extended to other safety protocols and executed several times during the course to assess the student’s learning progress.

Another study conducted with nurses found that they were involved in the educational actions of health services, primarily those that acted in a perioperative context, since they are part of nursing systematization, planning, and implementation of measures aimed at promoting nurse-patient dialog, establishing confidence, and minimizing doubts and factors in the surgical context of patients during their recovery (Bittencourt et al., 2021).

It is also known that the PNSP requires the inclusion of this topic in academic curricula, but there is no framework for its application, leaving the criterion to each institution (Ministério da Saúde, 2013).

“Patient safety” involves a set of common habits taught since the start of health training courses aimed at reducing or eliminating adverse healthcare events. According to Ortega et al. (2020), investment in education and nursing training decreases the occurrence of healthcare-related adverse events, given that these professionals are involved in important decisions, lead the frontline team, and, when well trained, provide safe and reliable care.

In this category, the topic was addressed based on knowledge shared in the classroom, with the positive aspects that students can apply in their professional learning. This knowledge consists of theoretical understanding, reading didactic material, group discussions, and abandoning common consensus for critical thinking based on the most recent literature.

3.2 Category 2: Learning “patient safety” in curricular internships

During a practical visit, students can identify the risk factors that induce errors, associating theoretical knowledge to the practical environment, resulting in self-criticism of the importance of using or not safety protocols, guaranteeing that learning occurs and that an important stage in their training is reached. Knowledge is considered complete when an action plan is devised to address healthcare errors, identifying shortcomings, and contributing to a critical-reflexive attitude of future professionals (Cauduro et al., 2017).

In the statements below, students recognize the application of content taught in the classroom, with some reservations, such as a lack of continuous training and interterm communication, resulting in the resistance of some professionals to following protocols.

I saw the course content applied in practice during my internship. In general, it is not implemented 100% as it should be, such as communication between the team and professionals who have worked in the area for a long time but don’t update their knowledge (STUDENT18).

In different internship moments, patient safety applications had the same rigor we learned in the classroom. The resistance of some professionals is a barrier to their application (STUDENT13).

The most common barriers are lack of materials, and lack of attention (due to tiredness), and organization in the sectors. This really compromises care and puts the patient’s life at risk (STUDENT27).

I´ve had experiences in places that do not follow protocols; unfortunately, I see an enormous deficiency in professionals and the institution because, in addition to not caring for themselves, patient care is also inadequate (STUDENT19).

However, as demonstrated in the statements below, all the students felt empowered and enriched with the knowledge acquired and understood that they have the necessary skills in their professional life to apply in the health units they are assigned to.

I believe that the theoretical knowledge obtained in the undergraduate course provides us with a foundation to apply in our nursing career (STUDENT26).

I believe that our training, from the first module until now, has qualified us to pursue our career and professional activities, which are supported by our consulting council (STUDENT5).

These statements show that the students’ experiences in their curricular internships and theoretical teaching confirm that knowledge is acquired by scientific reading, exchanging experiences with colleagues, critical-reflexive reasoning, and clinical practice. Students always look forward to this opportunity, which is even more important for constructing this knowledge. Recognizing inadequacies and knowing how things should not be done proves the importance of studying complex topics.

3.3 Category 3: Challenges to the implementation of protocols in the health units

At the start of the internships, many students observed an absence or partial application of patient safety protocols at the health units. In addition, the overall process was deficient, with a lack of basic materials and poor commitment from some professionals.

Our main weapon is scientific evidence because it allows us to make suggestions and improve the quality of our care. We know which safety protocols and measures we must follow, and we have a solid base, as do our colleagues (STUDENT18).

With respect to the difficulties faced in implementing protocols at the health units, the students frequently mention the resistance of professionals, disinterested management, and the lack of basic resources. This demonstrates the difficulties and facilities future nurses face in applying patient safety knowledge.

There is considerable demand for health-related courses on the part of professionals in this area, thereby enriching the theoretical and practical training of the students. However, professors are generally not qualified to deal with adverse event notifications or propose improvements to avoid them. In this respect, the challenge extends to the institution regarding teaching patient safety procedures and supervising their adherence and effectiveness, emphasizing teamwork (Bohomol et al., 2016).

In a study on implementing patient safety protocols, Reis et al. (2017) found that some professionals did not adhere to these protocols. This resistance is related to the organizational culture, fears and uncertainties of the professors, and the difficulty in leaving their comfort zone.

The most widely used words in the students’ statements are listed in the word cloud below in order of frequency (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Word cloud referent to nursing students’ statements about patient safety, 2022. Source: the authors

The word cloud originates in the main axis of the research. The “patient” is the focus of a nurse’s care and that of the health units, which seek to rehabilitate the individual’s health, followed by “safety,” the final product. Both words promote the patient as the primary client, followed by the “professionals”.

During the internship, students often mentioned the attitudes observed regarding adherence to patient safety protocols. Given that they are still in training, this observation is noteworthy, especially concerning imitating existing best practices.

The word “protocol” was also often cited since patient safety is based on protocols that guide professionals and management, contributing to academic training and the implementation of practices aimed at minimizing adverse health events.

Furthermore, the words “team” and “theory” were equally used. These allude primarily to teamwork to comply with protocols since the continuous nature of health care means that no professional works alone. The terms “know” and “university” appear in the statements since students there are first exposed to the topic at school. When their critical thinking has been formed and added to the scientific knowledge acquired in the theoretical-practical study, situations are judged based on their correct or incorrect application.

The words “attention”, “care”, “internship”, “experiences”, “management,” and facilities” are combined because they correlate mainly at the onset of the student’s clinical experience, where the material taught and discussed in the classroom is put into practice. Thus, professionals should pay close attention to avoid human errors.

In the case of “management” and “facilities”, the students’ statements reveal that when a hospital is well managed or whose administrator is concerned about protocols, it is reflected in the safety culture of the institution. Finally, the word “access” is related to professionals who have worked for a long time but have not stayed abreast of the latest medical developments to provide safer health care to patients.

The students’ statements demonstrated classroom learning, consolidated by practical experience and the challenges caused by the absence of protocols.

In some sectors, the professionals know a specific protocol but complain of work overload. This is unacceptable because quality care depends on following risk protocols (STUDENT18).

I believe we acquire this knowledge in the classroom, but we cannot restrict it to that environment; we have to constantly keep up with the latest developments in order to provide evidence-based care (STUDENT28).

Everything learned was very important because, when I arrived at a unit, I could detect errors and know what measures to take. Unfortunately, some professionals do not know these protocols (STUDENT01).

I´ve seen situations in which there was a protocol but the professional preferred to follow a different path, despite knowing its importance. This concerned me greatly, mainly because it involved basic vaccination protocols (STUDENT19).

Thus, the results presented clearly explain the students’ perception regarding patient safety in the undergraduate nursing course in the context of theoretical and practical teaching.

It can be observed that the categories address patient safety from university to professional practice at health clinics. Universities must be prepared to aggregate knowledge of their safety protocols, indicators, and sequential processes in all healthcare modalities, ensuring cohesive teaching. To that end, curricular frameworks should be revised to ensure that this knowledge is used in its entirety. Only well-learned in theory and clinical teaching settings will be suitably implemented in practice.

Student involvement resulted in pertinent questions since they openly discussed their perceptions about learning and the most common difficulties faced in the academic environment. This “real-life laboratory” students experience during the undergraduate course develops their professional self-confidence and improves their critical thinking, making all the difference in the health units they are allocated to.

To provide safe health care, all the professionals and administrators involved and the health units themselves must adhere to protocols and promote adequate patient safety measures (Azevedo et al., 2016).

4. Final Considerations

This case study used an online focus group, which showed that students are eager to acquire knowledge and experience what is being offered as much as possible. Thus, despite the professors' fragmented and voluntary patient safety teaching, students assimilate the general concepts well.

It is important to note that a specific qualitative research software was used, which was very useful for analyses and in the search for links between them (which would be impossible manually), in addition to combining all the information obtained in the evidence-based study.

The critical outlook of students will be essential to change the current situation at health units that do not adhere to patient safety protocols. As such, investing in this discipline will never be deemed excessive since, in addition to minimizing hospital costs in terms of treatment and avoidable adverse events, it will also preserve life.

4.1 Strengths and limitations of the study

Based on the nursing students’ perspectives of “patient safety” learning, the present study may help teaching institutions implement measures in their curricula, seeking appropriate methodologies or theoretical frameworks for their basic concepts in protocols recommended by the Ministry of Health. It is highly advisable that students graduate from university with this knowledge, enabling them to develop management and healthcare activities aimed at safe, effective, and economical safety practices.

A limitation of this study was being unable to access the PPP of participating students, which left a gap in the curriculum matrix regarding the insertion of “patient safety “and the methodologies used.