1. Introduction

In 1975, Texas passed a law granting school districts the authority to deny undocumented children access to K-12 education. However, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Plylerv. Doe (1982) ruled that Texas’ law was unconstitutional, violating the equal protection provision of the Fourteenth Amendment. Plyler referenced the Brown v. Board of Education(1954) decision that ended Jim Crow segregation in American schools, arguing that education was essential to securing every person’s ability to develop productive lives and preventing a permanent underclass from forming in America (Motomura, 2014).

Despite education being a fundamental right, it is fragile and contested for undocumented immigrants. Federal courts have had to reaffirm Plyler multiple times, including issuing a permanent injunction over California’s Proposition 187 (1994), which banned undocumented children from K-12 public schools and required teachers to report suspected undocumented people to federal immigration authorities. More recently, the courts blocked Alabama’s HB 56 (2012) provision that required schools to check and report newly enrolled K-12 students’ immigration status. Beyond K-12 schooling, the entanglement between education and immigration has grown because of the federal immigration law in 1996 opening the door for states to ban or restrict, or move in the opposite direction of expanding, the right to postsecondary education.

These policies have a significant impact on all immigrant students, but especially the 1 million undocumented students attending K-12 schools and an estimated 10,000 enrolling in college each year (Zong & Batalova, 2019). For example, scholars show that the presence of immigration enforcement harms, and its absence improves, educational outcomes for K-12 immigrant students (Amuedo-Dorantes & Lopez, 2017; Bellows, 2019; Corral, 2021; Dee & Murphy, 2020; Kirksey et al., 2020). While a rich interdisciplinary scholarship covers the development of these policies and their effects, no systematic study examines news framing of the intersection between education and immigration.

A consensus has been forged among scholars that immigrants contribute more to the economy than they receive through public benefits (Becerra et al., 2012; Brannon & McGee, 2021). Scholarly consensus also shows that immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than their non-immigrant counterparts and that jurisdictions with pro-immigrant policies have lower crime rates and are safer (Martínez-Schuldt & Martínez, 2019, 2021). Yet, framing remains a powerful influence, capable of swaying public opinion, informing policies, and ascribing identities to immigrants (Chavez, 2013; Ngai, 2004), making news framing at the intersection of education and immigration timely and crucial to ongoing public and scholarly debates. Indeed, California's infamous Proposition 187 justified its ban and local enforcement of federal immigration law by falsely linking undocumented immigrants to the state's "economic hardship" and to "criminal conduct" generally (Colbern & Ramakrishnan, 2021, p. 328).

We examine 40,469 news articles published from 1980 to 2022 in six national and state news sources in the United States to explore the (dis)connections between education (K-12 and postsecondary) and immigration. Combining machine learning techniques and social network analysis with qualitative coding, we show that reporters’ use of a range of experts creates a deep conflation of education with immigration enforcement and illegality framing. Despite quests for journalistic neutrality, we argue that the use of experts by reporters prevents immigrant education from being a topic on its own or a topic where immigrants are framed in a positive light. The article concludes by suggesting future directions for research that links news framing to public opinion and policy developments.

2. News Framing and the Experts Behind the Framing

Reporters do much more than communicate neutral details: they construct frames, contextualize, and attach meaning to policies, debates, and affected communities. For immigrants, binaries of us/them, legal/illegal, or citizen/immigrant, often overarch framing of the issues and immigrants (Hamlin, 2021; Huber, 2015), resulting in normalizing exclusionary language and thinking about immigration and immigrants (Chavez, 2013; Dingeman-Cerda et al., 2015; Gleeson, 2015; Heredia, 2015; Nájera, 2015; Patel, 2015). Importantly, scholars show that these binaries occur in both progressive and conservative news sources (Cruz & Holman, 2021; Fleming-Rife & Proffitt, 2004; Patler & Gonzales, 2015; Rendon et al., 2019).

The experts that reporters rely on for information also play an essential role in constructing news frames. Henig (2008) and Yettick (2015) find that reporters rely on experts they perceive as newsworthy more than experts whose knowledge is peer-reviewed. Reporters also seek experts they find controversial (Merkley, 2020). Framing immigrants and the expertise behind this framing is shown to have a strong impact on public opinion and behavior (Haynes et al., 2016; Newman et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2019). This article contributes to the interdisciplinary scholarship on media and framing by exploring the kinds of binaries ascribed to immigrants in news covering education and the contrasting role of different types of experts. It also situates media and framing in immigration scholarship on illegality (Cohen, 2020; Ngai, 2004), immigrants living in a liminal status (Gonzales, 2008, 2011, 2015), and policy (Colbern & Ramakrishnan, 2021).

3. Figures and Tables

We analyzed 40,469 news articles from 1980 to 2022, collected by querying the ProQuest news database for mentions of (im)migrants (e.g., DACA, Dreamers) combined with education (e.g., tuition, financial aid, college). This allows us to capture how prominently immigration’s entanglement is via the news framing of immigrant education. We did not include immigration or terms relating to immigration politics, law, or enforcement, to ensure that we only capture education-specific frames of immigrants.

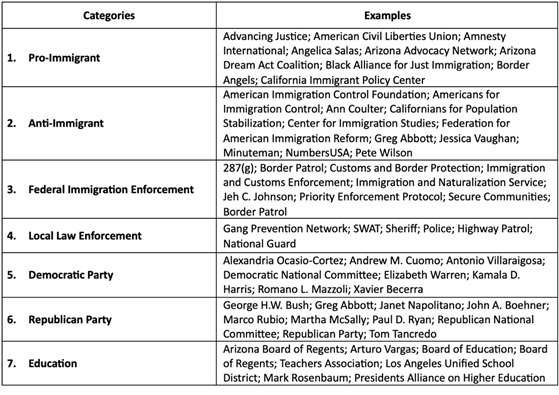

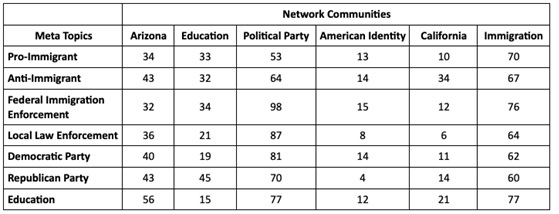

Next, we developed an original framework with seven categories to capture the relationship between experts and frames that (dis)connect immigrant education and immigration. Our categories begin with pro/anti-immigrant rights leaders or organizations, which we define as entities having a clear role in policies that expand or restrict immigrants’ rights at the national, state, or local levels. We develop other categories to distinguish between law enforcement experts specific to federal immigration enforcement and local policing, the two political parties, and officials specific to education (see Table 1 below).

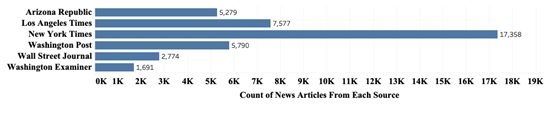

Our corpus of news articles includes two progressive (New York Times; Washington Post) and two conservative (Washington Examiner; Wall Street Journal) national news sources.

We employed a most-likely case selection approach for including two regional-local news sources that vary on their immigration policy environments: Los Angeles Times in California (the state with the most pro-immigrant policies) and Arizona Republic in Arizona (the state with the most anti-immigrant policies) figure 1 (Colbern & Ramakrishnan, 2021; Seawright & Gerring, 2008). Our six news sources capture different levels of government, progressive and conservative outlets, and varying immigration policy contexts.

We downloaded all news articles from the six sources as HTML files and developed a custom scraper designed to extract metadata (author, title, outlet, and publication date) and the full text. We then used the Spacy Python library and its medium pipeline (en_core_web_md 3.5.0) to conduct Named Entity Recognition (NER) across the corpus, which identified a total of 284,652 organizations and people (Honnibal & Montani, 2017). We filtered this entity list to only entities with a frequency of five or more mentions in the corpus, resulting in a list of 28,227 entities. Entities from this list were hand-coded for our seven categories of expert type. We supplemented this process by including additional names of pro- and anti-immigrant entities from an original dictionary. We then queried the corpus with the list of entities for each category and created a dataset of all articles mentioning one or more of the entities, resulting in seven unique datasets - one for each entity type.

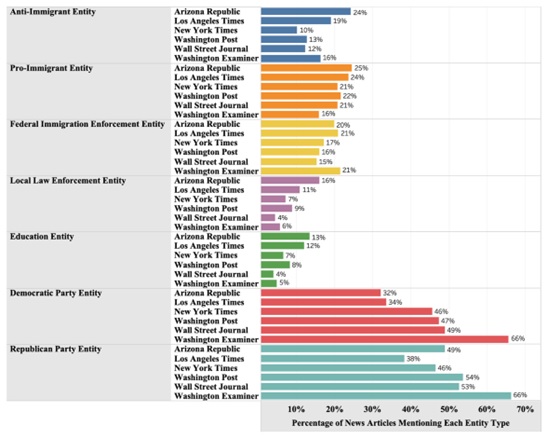

Figure 2 above summarizes the percentage of articles mentioning each entity type for the six news sources. As expected, differences exist between progressive and conservative news sources: The New York Times (progressive) has the lowest percentage (10%) of articles mentioning an anti-immigrant entity, and the Washington Examiner (conservative) has the lowest percentage (15%) of articles mentioning pro-immigrant entities. However, all six news sources contain the seven entity types, and they all appear to show similar differences in frequency across each entity. The Democratic and Republican entity types are covered in a much greater percentage of news articles, the education entity type being covered the least, and the pro/anti-immigrant and law enforcement entity types falling somewhere in between.

4. Quantitative Methods

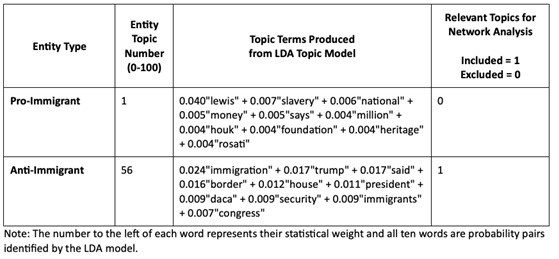

We apply topic modeling and social network analysis to produce a meta-analysis of framing through keywords shared across the seven entity types. For this, LDA topic modeling was used to identify 100 topics for each entity type (Blei et al., 2003). While we cannot isolate one entity from another because of their high overlap rate in the data, topic modeling captured each entity’s influence on framing through their respective 100 topics. We cleaned our dataset by qualitatively examining each entity’s 100 topics, selecting relevant topics that mention education, immigrants, or immigration, and excluding irrelevant topics - producing a dataset of 248 highly relevant topics (see Table 2 below for examples).

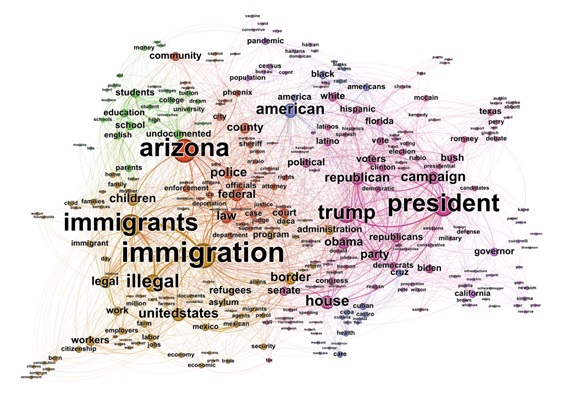

We ultimately analyzed news framing at the corpus level through a network, which we produced from the 248 topics’ terms and connections between terms. Using Gephi’s community detection algorithm (Bastian, et al., 2009; Blondel, et al., 2008), we captured six unique communities composed of highly connected nodes and edges (shown in Section 6, Figure 5). Each node (circle) represents a term in the topic model. An edge (line) between nodes occurs when two terms appear together in the same topic - the more times the two terms appear together, the higher the weight of that connection.

For example, the “Anti-Immigrant” meta topic in Table 2 above creates edges between the nodes “daca” and “trump.” We iterated this process through all topics. Table 3 above summarizes the number of connections between the six network communities and seven meta topics.

5. Qualitative Methods

Data science techniques allowed us to structure our qualitative analysis of 1,451 news articles using MAXQDA for content analysis. This included structuring our focus to pro- and anti-immigrant entities, which we expected to be most likely to frame immigrant education differently from one another (Bennett & Elman, 2006). Data cleaning allowed us to remove 452 of 700 topics and their respective news articles, which structured our content analysis to be more specific to education and immigration. We also employed comparative case-study methods around the two most-likely states where news coverage of immigrant education would vary on framing due to having oppositive immigration policy environments (Seawright & Gerring, 2008).

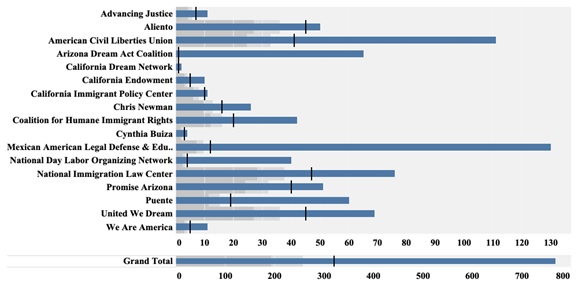

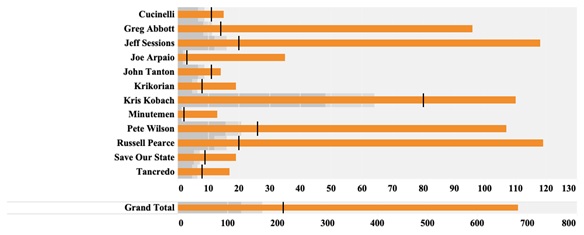

Using MAXQDA’s dictionary tool, individual entities in the pro- or anti-immigrant types identified as important nationally or in California and Arizona were coded. All news articles were coded for entities who are mentioned in less than 130 news articles, like the California Immigrant Policy Center. Randomly selected subsets of news articles were coded for entities who are mentioned in more than 130 news articles, which we distributed across the six news sources.

We first coded text for whether the entity is mentioned as an expert or background and whether the entity produced a positive or negative framing of immigrants. This process allowed us to focus content analysis on the role pro- and anti-immigrant experts played in framing immigrant education and how reporters relied on these two sources and their expertise. We defined being an expert as being quoted, paraphrased, or actively informing the framing of the news article. Intercoder reliability was conducted in the early stages of the coding to identify differences between coders, which we conducted on sub-sets of 10 articles for each entity. Once a Kappa value greater than .90 was reached on the sub-sets, larger randomly selected sets were divided across the team and coded (O'Connor & Joffe, 2020).

Of the 1,451 entities in our coded sample of articles, 533 were coded as experts that produced framing. We proceeded by coding the 533 articles to qualitatively capture expert framing. Figures 3 and 4 above provide an overview of the coded entities. Counts left of the black bar represent the number of times a mentioned entity is coded as an expert and counts to the right of the vertical black bar represent those coded as only background. Later in Section 7, we discuss our qualitative findings and connect them to our quantitative findings, which we turn to first in Section 6.

6. Enforcement, Illegality, and Partisan Framing

Our central finding is that federal and state-level immigration enforcement, notions of illegality, and partisan division over immigration are all prominently woven into the framing of immigrant education. Network analysis sheds light on the differing frames, but also highlights how reporters' balancing of perspectives between pro- and anti-immigrant entities, as well as Democratic and Republican entities, ends up conflating the coverage of education and immigration enforcement. Terms like family and home appear next to the framing of education and the legal pathway to citizenship. However, these terms also connect to harmful binaries such as legal/illegal and foreign/American, which our network shows to be more pronounced. Please note that we use the term community in our analysis to reference the six detected communities of the network.

The top left of our network shown in Figure 5 above and colored green is the "Education" community, which comprises terms like undocumented, students, schools, college, university, tuition, dream, bills, and legislature. This community only includes one term - "English" - that is noticeably exclusionary, referencing policies requiring English-only education. While this community appears positive overall, it strongly connects to two communities that feature immigration enforcement. The Education community’s edges connect to the orange "Immigration" community in the lower left of the network, through the terms Immigrant(s), kids, child, home, and households. Within the Immigration community, the term DACA is distant from the Education community’s edges and clustered near terms referencing immigration, legality, citizenship, border, security, deportation, and economy. These examples highlight how immigrant education is framed in connection to federal immigration enforcement.

The red “Arizona” community has strong ties connecting it to the Education community, highlighting another way that immigration enforcement frames education - through state and local immigration efforts. Arizona’s infamous anti-immigrant Sheriff Arpaio and State Senator Russell Pearce are key terms in the community and were key figures in the passage and implementation of Arizona’s SB 1070 in 2010. This law carved out comprehensive state powers over immigration enforcement, including empowering state and local officials to target immigrants for removal, making it a state crime to fail to carry proof of lawful status, banning local sanctuary policies, and criminalizing the transporting of an undocumented person as harboring. In Arizona v. United States (2012), the US Supreme Court ruled most of SB 1070 as preempted by federal immigration law, but it upheld the state's ability to require that local law enforcement asks for proof of legal status during routine traffic stops. References within the Arizona community to courts, Immigration Enforcement and Customs (ICE), and local law enforcement, all highlight the importance of immigration for Arizona's politics. This includes education. Arizona led the nation in passing restricting laws banning undocumented and DACA-status residents from accessing in-state tuition or financial aid support when attending colleges and universities, banning ethnic studies in high school, and requiring English-only classes in K-12 education.

Most surprising is the absence of pro-immigrant rights framing and the domination of anti-immigrant framing in the "California" community. California has a strong anti-immigrant history, but Proposition 187 in 1994 marked a turning point for the state on immigration. California soon became a leader in pro-immigrant policy.

It was one of the first states in 2001 to grant in-state tuition to undocumented students. In 2011, California was the first state to grant undocumented students non-state-funded scholarships for public colleges and universities, and state-funded financial aid such as institutional grants, community college fee waivers, the Cal Grant, and the Chafee Grant. In 2014, California continued leading other states by establishing a State DREAM Loan Program. Significantly, this pro-immigrant history is absent, whereas California's anti-immigrant leadership in the 1990s, with Proposition 187 and Wilson, is prominently featured in the California community of our network (Colbern & Ramakrishnan, 2018, 2021). This illustrates how the news prioritizes anti-immigrant framing.

The small size of the California community contrasted with the large size of the Arizona community, similarly reveals how powerfully the news connects immigrant education to immigration enforcement. This contrast is surprising taking into consideration that the California news source (Los Angeles Times) had 2,298 more articles compared to our Arizona news source (Arizona Republic). We would expect to see the pro-immigrant framing heavily featured in the California community, but this is not the case. A key takeaway is that the achievements on immigrant rights over the past two decades, especially in California, have not translated into framing immigrant education separate from immigration enforcement in our corpus of national and state news sources.

Partisan division similarly conflates immigrant education and immigration. “Dreamers” belong to the “Political Party” community situated near Presidents “Obama” and “Trump.” First proposed in 2001, the federal Dream Act has been reconsidered multiple times over the past two decades but has failed due to partisan division. Anti-immigrant leaders like Kris Koback, Jeff Sessions, and Breitbart, are prominently featured in the Political Party community of the network, making it clear that extremist and nativist framing of immigrants is prominent in the news coverage of immigrant education. Finally, a small “American Identity” community is colored in purple and includes references to racial and ethnic groups and healthcare but has less relevance to the framing of education.

7. Counter Framing at the News Article Level

The framing of immigrant education in our network raises important qualitative questions about experts' roles in producing these frames. As we show earlier, pro-immigrant entities are slightly greater in their percentage of news articles than anti-immigrant entities, which we expect to produce counter-frames or positive frames about immigrants' value and contributions to society. This section offers qualitative analysis and insights into why we see such harsh binaries in the corpus. More importantly, it reveals frames that are not captured at the corpus level that counter the enforcement and illegality framing but are structured within the broader context of an immigration debate. Our analysis focuses on these kinds of (dis)connections between the corpus level and individual news article level framing while showcasing the crucial importance of reporters' reliance on experts for framing immigrant education.

Carlos Garcia, Puente’s Executive Director, is referenced in The New York Times as directly challenging using binaries to frame young immigrants. The reporter situated Garcia’s expertise and view as being “irritated by the Dreamers’ tendency to portray themselves as innocent victims, a tactic that opened the door for conservatives to speak of Dreamers with empathy even as they cracked down on their parents as ‘criminals.’” In the same article, Erika Andiola, President of the Arizona Dream Act Coalition, explicitly critiques framing immigrants through binaries centered around immigration. “A lot us feel like we sort of shot ourselves in the foot . . . [b]ecause we started that narrative like ‘I was brought here by my parents, not my fault, poor me, I was here as a child' that kind of created blame on our parents.” The reporter who cites these pro-immigrant experts goes on to explain how Arizona’s harsh anti-immigrant law, SB 1070 (enacted in 2010) obligates local law enforcement to question anyone that they had ‘reasonable suspicion’ to believe was undocumented and how this impacts Dreamers and their parents, who are now more likely to face immigration enforcement and possibly be deported (Valdes, 2017).

Rarely but on some occasions, we found that pro- and anti-immigrant entities were the authors of the news articles, allowing them to control the framing entirely. For example, in the Arizona Republic, Puente’s Executive Director Carlos Garcia, wrote an article defending immigrant’s right to education and challenging harmful immigration binaries used to frame immigrants.

“The purpose of the tuition restriction bills and English-only proposals that came before the 2010 racial profiling law and the introduction of its successors . . . [are] an attempt to create a separate, cruel, and costly criminal justice system for undocumented people. . . . And in Arizona, it's used to drown us.” Garcia re-centers the framing around family, explaining: “that labeling can only take place when it's not your family. We say not one more deportation because removals are not a theoretical question for us. It’s a question of the cousin doing extra time or the uncle who's no longer at family dinners because our allies decided to ‘choose their battles’ and our family’s togetherness didn’t make the cut” (Garcia, 2016).

Pro- and anti-immigrant entities are both provided space in progressive and conservative news outlets alike. The Washington Post (a progressive outlet) published an authored article written by Dan Stein, President of the anti-immigration organization Federation for American Immigration Reform. In "Doing Right Is Nativist?,” Stein adamantly defends restrictions on immigrant rights and harsh enforcement, saying: "The impact of illegal immigration on education, health care and law enforcement is felt at the local level. There is nothing toxic or nativist about local governments deciding not to provide nonessential benefits and services to people who have no right to be in the community in the first place, or to crack down on employers who hire them" (Stein, 2007). Featuring this article authored by an anti-immigrant spokesperson is likely in an effort towards journalistic neutrality, but the result is a frame of immigrant education that emphasizes immigration enforcement.

Explicit counter-framing between pro- and anti-immigrant entities within news articles is another way that that immigrant education is connected to immigration. For example, an Arizona Republic reporter references Jonathan Blazer, an attorney representing the pro-immigrant entity, National Immigration Law Center, to critique the anti-immigrant entity Center for Immigration Studies. Blazer is quoted saying: “‘This is an old CIS trick. . . . They do it to make it look like immigrant households are welfare users and dependents and especially likely to be on welfare programs because it serves their express agenda’ of controlling immigration and limiting access to public benefits by immigrants” (Gonzalez, 2011, 2011). Similarly, a reporter from the Washington Examiner references a report written by Matthew J. O'Brien, research director for the anti-immigrant entity Federation for American Immigration Reform, to critique progressive immigration scholarship and think tanks. O'Brien is quoted saying: "Many pro-mass migration organizations do not want Americans to know just how big our illegal alien problem really is. Therefore, to minimize the problem, they engage in all manner of mathematical gymnastics to produce illegal alien population estimates that they see as tolerable, to the bulk of American society" (Bedard, 2019). Another Washington Examiner article references a report published by FAIR to frame the cost of "illegal immigrants and their kids" as a loss of "$135 billion a year, the highest ever, driven by free medical care, education and a huge law enforcement bill." The reporter goes on, explicitly connecting FAIR as producing "the most authoritative report on the issue yet" (Bedard, 2018).

The framing of immigrant education around immigration is most clearly articulated by reporters referencing anti-immigrant entities who challenge the constitutional right to K-12 education. The anti-immigrant entity Save Our State Committee is referenced by a Los Angeles Times reporter to explain why California’s anti-immigrant Proposition 187 (1994) was supported, despite the conflict this created with the Supreme Court decision in Plylerv. Doe (1982) (Feldman, 1994). Nearly three decades later, and after Prop. 187 was overturned as unconstitutional, anti-immigrant entities continue to be referenced by reporters for expertise that explicitly justifies attempts at denying immigrant children a right to K-12 education because of their legal immigration status. Recently, Governor Greg Abbott of Texas is quoted saying: “With the Supreme Court signaling a willingness to reverse decades-old precedents like the Roe v. Wade decision on abortion . . . he would seek to overturn a 1982 court decision that obligated public schools to educate all children, including undocumented immigrants” (Goodman, 2022).

A key qualitative finding of our article is that organizations and leaders of both entity types engage with immigration-based binaries. What we cannot see from a corpus-level network analysis is that pro-immigrant entities often intentionally break from binary framing. However, this effort is couched in language making the binaries more visible. Pro-immigrant entities are forced to react to harmful binaries and therefore are rather unable to construct separate education-specific frames. Meanwhile, anti-immigrant entities intentionally reinforce exclusionary binaries, further normalizing and anchoring harmful frames around enforcement and illegality in the coverage of immigrant education. These subtle nuances in our qualitative coding help explain why illegality and enforcement are so prominent in our network analysis.

8. Limitations and Future Directions

Through a combination of a custom scraper designed to extract article metadata, using NER and LDA to identify patterns in the corpus, and conducting network analysis across meta topics, this article scales analysis of media framing to tens of thousands of news articles. This includes analyzing patterns in framing at the corpus level paired with qualitative analysis of framing at the individual news article level. We contribute to scholarship on media framing, immigration, and education by revealing mostly harmful framing and explaining why and how these frames emerge from experts and dynamics that prevent reporters' quest for neutrality.

Our use of quantitative and qualitative methods is specific to framing at the corpus level, not the fuller diversity and complexity of frames elsewhere. Future research should unpack the diversity and nuances of frames at other levels of analysis, beginning with the topic level. A deeper examination of each of our 248 highly relevant topics would capture greater diversity and connections between frames and experts. Future research should also delve deeper through comparative, qualitative, exploratory, or grounded approaches, at the topic level, news source level, and news article level, to capture a fuller range and diversity of frames and roles of expert types.

Importantly, our findings demonstrate that future research, regardless of method or level of analysis, should take seriously how framing emerges and changes around key events. This includes periods and events specific to immigration and specific to education, such as efforts to enact federal immigration reform, state laws providing undocumented Americans equal access to in-state tuition or financial aid, and laws regulating K-12 and postsecondary education for everyone regardless of immigration status. Explaining media framing requires this kind of attention to political history and conceptualizing the media as a political institution that impacts social movements, public opinion, and policy developments.

9. Final Considerations

Plylerv. Doe (1982) is the only time in American history that the U.S. Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection clause has been applied to the rights of undocumented immigrants. Yet, education as an essential right is at stake for children growing up in the United States who identify as American but lack legal immigration status. How the news frames immigrant education and whether this is connected to immigration is crucial for understanding how and why Plyler has yet to be fully realized and embraced.

Our analysis shows that, from 1980 to 2022, reporters too often cover the education of immigrants through frames based on immigration enforcement, illegality, and partisan division. Network analysis reveals how the conflation of education and immigration occurs across news outlets regardless of their ideological leaning or location. We argue that this entanglement is largely due to the complexities and embeddedness of binaries originating from conservative immigration tropes, which obfuscate meaningful discussion or news coverage of education. Qualitative content analysis reveals how the experts' reporters rely on play a role in framing education in connection to immigration. Pro-immigrant experts struggle to reframe education and immigrants away from immigration enforcement, while anti-immigrant experts actively reinforce immigration enforcement and illegality in coverage of immigrant education. As a result, positive frames of immigrants or education remain limited because the news intimately links them to immigration enforcement, legality, and divisions over reform. These findings suggest that the quest for journalistic neutrality is impossible and that current efforts to bring in varying perspectives from experts prevent immigrant education from being a topic on its own or from being a topic that positively frames immigrants.

These findings hold tremendous consequences. Since 2012, DACA has provided more than 600,000 immigrant children with temporary lawful status prohibiting their deportation, among other life-changing provisions. In October 2022, the federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that DACA was unlawful. The partisan division has fueled a fight over DACA and the fate of Dreamers, with nine Republican-led states arguing that DACA costs states millions of dollars in health care, education, and other costs. Under the Biden Administration, the U.S. Justice Department defends the program and is working with Democratically led states and pro-immigrant rights advocacy organizations, to argue that DACA recipients are productive drivers of the economy and deserve a pathway to citizenship. The media is not simply situated outside of this fight or formal politics as a neutral purveyor of information. It is active in (re)framing politics, education, and immigration, with tremendous consequences for the lives of immigrants in the United States.