Introduction

The importance of trust in government, social capital, and political beliefs as drivers of compliance has been analysed since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, as comprehensively reviewed by Fancourt, Steptoe & Wright (2020); Giuliano and Rasul (2020). In a recent paper, Drylie-Carey, Sánchez-Castillo & Galán-Cubillo (2020) even discussed the European leaders’ communication strategy on Twitter during the pandemic and highlighted the importance of political communication. The issue of trust in government is extremely relevant and actual. People around the globe in 2020 have been imposed very demanding limitations on some of the most important civil rights in the form of social distancing and isolation, travel restrictions and closure of many activities and leisure centers. These measures have had strong effects at both the societal and the economical level, such as job loss, increasing unemployment rates, significant GDP losses and mental well-being issues (World Health Organization, 2020). Therefore, in such a unique situation, examining the levels of public trust is of paramount importance. This is both because, on one hand, public institutions must inspire trust in their citizens to make said measures effective through collective compliance, while, on the other hand those very same institutions need to trust their citizens in order to contain the spread of the disease and progress with their sanitary, economic and social recovery plans.

Therefore, this paper is focused on public trust, with particular attention on the importance of political leaders' speeches during the COVID-19 crisis. This research analyses speeches from the British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, the Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte and the Chinese President Jinping Xi during the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically around the beginning of the crisis and at its peak, while comparing the public trust levels in the three countries. Due to the different political systems between China and its European counterparts, conclusions are drawn not only based on the speech analysis of the political leaders, but also by considering that a comprehensive evaluation is the result of different cultural backgrounds and social systems.

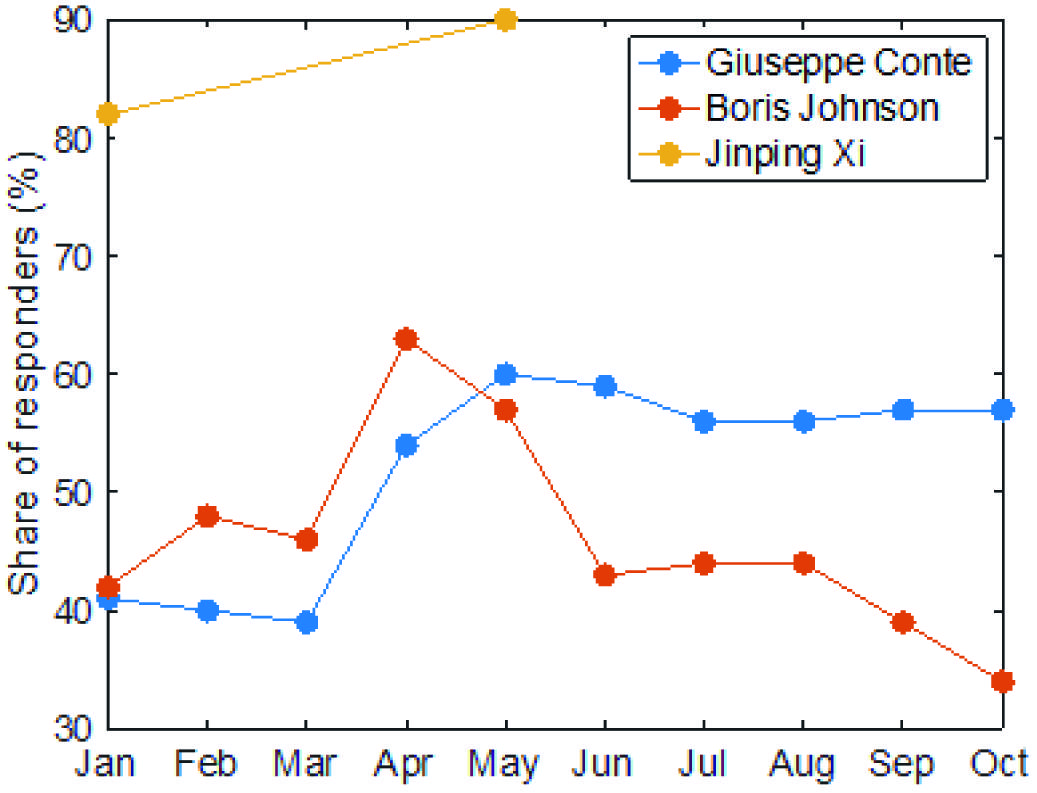

Drawing from Habermas (see Habermas, 2000: 22-23; see also Cooke, 1997; Habermas, 1984) and Bourdieu’s (see Bourdieu, 1991) theories about authentic and strategic communication, I analyses the effectiveness of different speech styles of political leaders and the ways they communicate with the public. Different speeches have led to different public reflections and reactions. While Boris Johnson’s speeches can be considered decisive but cold and often detached, Conte’s communication has often been more inclusive, encouraging and even friendly at times. Chinese President Jinping Xi showed instead a combination of authoritative and compelling manners when communicating to the Chinese public. Accordingly, the public trust in Boris Johnson's government as a source of information about coronavirus has declined substantially since April 2020, along with trust in politicians and news organisations in general. Conversely, the Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte earned significant credit during the battle against the pandemic. Finally, survey data for China shows a significantly higher level of public trust in Jinping Xi and the government compared to both the UK and Italy (Edelman, 2020).

The relations between authentic and strategic communication

It is well known that political speech plays a critical role when members of the public are evaluating politicians. Specifically, voters in liberal democracies seek for determined qualities in political leaders (Bailenson et al., 2008; Lalancette; Raynauld, 2019). Speech plays a key role in the interpretation of a message for many reasons, as speech is perceived as the best tool to effectively present information that is relevant in a political debate (Birdsell; Groarke, 2007; Alonso-Muñoz; Casero-Ripollés, 2020). During the initial spread of COVID-19 worldwide, most of the politicians’ speeches were broadcast in full on national television in the form of press conferences, thus reaching not only the audience physically present in the auditorium but also the nation as a whole. As a consequence, such speeches have been very much a showcase for each politician and have inevitably led to comparisons between them in terms of their respective leadership qualities.

It is therefore important to define the notion of authenticity in communication in order for politicians to appear trustworthy when communicating to their own citizens. "Authentic communication" include speeches characterized by sincerity and truthfulness, whereby sincerity implies saying what you mean, that is openly showing your intentions, thoughts and feelings (see Bohman and Rehg, 2014). Truthfulness means to say what is true. (Williams, 2010:20). These two terms are central for Habermas and Bourdieu, who have used them as a way to measure an actor’s authenticity and to define the necessary conditions for communication to be perceived as authentic. The literature below will focus on the two perspectives of communication: authentic and strategic communication.

Previous studies (see Holdo, 2020; Ojha & Ojha, 2006; Benson, 2009) have considered Habermas's theories as the basis of authentic communication, while using Bourdieu's perspective to understand why actors comply with sincerity and truthfulness. However, in the context of political communication, we need to combinate ethics and motivation. In fact, in order to earn the trust of citizens, political leaders must recognize that sincerity and honesty are both right and needed. Hence, discussing authentic communication and strategic communication is of great significance to understand political leaders' speech to the public during COVID-19.

Habermas's central claim about communication is that authenticity allow for a deeper and more sustainable collaboration than strategic communication. By ensuring a mutual understanding, actors can reach agreements which are not influence by their self-interest (see Habermas, 2000:22-23; See also Cook, 1997; Habermas,1984). This ethically oriented approach can in fact explain how people build trusting relationships by not using strategy or be driven by self-interest when communicating. For instance, secret conversations between friends, religious confessions, and therapy are types of communications that could not be maintained if participants don't believe that the other actors are sincere and authentic. Similarly, the efficacy of political communication critically depends on the speaker's ability to convince the audience about their sincerity and authenticity. A politician who is exclusively guided by self-interest is not a good politician, in any political or societal system. This distinction between goal- and interest-oriented conversations and selfless, sincere communication is necessary for understanding effective political discourse (Holdo, 2019; Markowitz,2010; Williams,2010). This dichotomy suggests that, on the one hand, political communication is just a strategy and a tool to convince people. However, at the same time, it must also entail truth and have people’s interests at its heart; in other words, its goals must be connected to people's experiences, feelings, and values for it to be meaningful.

In fact, experienced political leaders, especially in electoral systems, must use authentic communication. Political promises made during campaigning become meaningless if people do not believe them to be truthful. Similarly, in international politics, negotiators are more effective if the other side considers them trustworthy. In general, authentic communication enables to reach a consensus without relying solely on self-interest or coercion of the audience. Instead, authentic communication makes communication effective by exploring shared beliefs and considering the audience’s perspectives (Holdo, 2019; O 'mahony, 2010).

Bourdieu's view of real (or "selfless") communication, on the other hand, is quite different from Habermas's. In Bourdieu's works, the concepts of truth and authenticity are viewed as as strategic tools (Bourdieu, 1991) and may, in principle, serve any political purpose (Holdo, 2020). Bourdieu basically argues that communication always involves some level of struggle between actors with different interests, social status and ways of power. As for truthful and really authentic communication, Bourdieu believes it to be too idealistic, without any real value (e.g. Bourdieu, 1991) and more as a tool for hiding power relations and governance techniques (Holdo, 2020). In other words, Bourdieu thinks that real, non-strategic communication between people is impossible and power interests shape all forms of communication. As he puts it: "the relationship of language is always the relationship of power" (Bourdieu and Vacante, 1992:118), and "the power of words is nothing more than the delegation power of spokesmen" (Bourdieu, 1991:107).

Methodology

The article analyses two speeches delivered by the Chinese President Xi Jinping in February and in April 2020: "Speech on Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak" (Xinhua News Agency, 2020) and "Speech on the deployment of resumption of economic after the pandemic" (Xinhua News Agency, 2020). British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s delivered daily press conferences on the spread of the COVID-19 across March and April 2020 (Prime Minister's Office, 2020). This article focusses on the speeches given on March 3rd, March 12th as well as on the public panic caused by the absence of British Prime Minister Boris Johnson in April. Finally, Italian Prime Minister Conte's speeches (Italian Government and Administrative Adviser, 2020) was excerpted from March 9th and 11th when the outbreak was in its early stages in Italy; and in April, when the pandemic was largely contained but lockdown continued to be deployed. The timing of political leaders' speeches is based on the phases of the pandemic as announced by governments and classified as the early stage beginning and peak of the pandemic. This temporal classification approximately matches the epidemic curves reporting the number of new daily cases and deaths as gathered from the respective official government dashboards reporting on the evolution of the pandemic. Specifically, the peak was identified to be in early February in China, late March in Italy and late April in the UK. Following on this temporal classification for each country, this research employs mixed methods, including language and discourse analyses of the speeches retrieved from the official government websites, as detailed above.

The following line charts show the ups and downs of the approval rating of governments as surveyed by British, Italian and Chinese citizens and will be extensively commented over the course of the entire manuscript (Edelman, 2020).

A comparison between UK, Italy and China political leader's speech.

4.1 At the beginning of the pandemic

Jinping Xi delivered a speech on a meeting on February 3rd, after the World Health Organisation (WHO) listed COVID-19 as an international public health emergency. This was the first time that the President appeared in front of the public since the virus outbreak in Wuhan in early January 2020. Jinping first heartfeltly thanked the Chinese doctors and nurses who worked at the front line of the epidemic and extended sincere condolences to the families who lost loved ones. In his speech, Xi put forward a slogan to boost morale among the people in Wuhan, which sounded like a sincere statement:

“First, the whole Party, the whole army and the people of all ethnic groups stand with you (Wuhan) and strongly back you. Secondly, life is more important than Mount Tai. Thirdly, everything about pandemic must be in order, and prevention is everyone’s responsibility. Fourth, we (entire country) should strengthen our confidence, help each other, because we are all in the same boat, prevent and control the pandemic following science and make targeted policies to stop the disease” (Netease,2020).

He then added:

“We should put the life safety and health of the people in the first place, and regard prevention as the most important task at present. The local governments should report on the situation of the pandemic and control it in a timely manner. Governments at all levels should cooperate with each other to support the supply of drugs and medical equipment” (Netease,2020).

At the initial stage of the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, there was no doubt that this was a decisive, authoritarian but also inspiring response. This is in line with the style of the Chinese central government in responding to crises and challenges, which is based on the key idea "see things early, move quickly" as an important principle for successful risk management. In addition, the acknowledgements at the beginning of the speech stimulated Chinese citizens who fought against the pandemic, in particular the health care workers who were the first to face the pandemic. Even though other political leaders will also thank the healthcare systems and the citizens for their efforts, in the first place, Jinping Xi also highlighted four key points as a model for political leaders. This is something typically absent from different social and political systems and style of communications. Moreover, the sentence "the whole party, the whole army and the people of all ethnic groups stand with you and strongly back you" has brought courage and confidence to Wuhan’s residents who were struggling in the pandemic. In fact, since China was the first country to face the outbreak of the unknown respiratory disease, residents of Wuhan panicked, so that it was essential to for the President to reinsure them. In particular, President Xi did not highlight personal heroism and political achievement at all in this speech but used 'the power of all Chinese people' as the subject and 'strong backing' as the object, which thanks the Chinese people for the efforts and contributions to fight the pandemic.

"Uniting all forces" in Jinping Xi's speech is a concept first put forward by Chairman Mao during the 20th-century Sino-Japanese wars (Zhang, 2020), and carries a lot of weight for Chinese people. The fact that Jinping Xi used this concept and applied it to the pandemic crisis arose unity, courage and pride in the Chinese people. He then continued with: "Life is as important as Mount Tai", which he used as a metaphor. Here, Xi Jinping referred to Mount Tai, a mountain of particular historical and cultural significance, in order to evoke ancient religious feelings. In fact, on Mount Tai monks used to perform rites to seek protection from floods and earthquakes.

The President then followed with: “everything about the pandemic must be in order and prevention is everyone’s responsibility”, which emphasizes the power of Chinese people and embodies Jinping Xi's ruling idea of respecting the value of the subject. At the same time, this sounds like a warning and with tones of dictatorship. Xi mentions the two disputable words “order” and “responsibilities”. In the Chinese societal context, “order” stands for the army and the police, which means that, in this crisis, any violation of order and destruction of unity would be severely punished. “Responsibility” in the Chinese context can be understood as “take responsibility or you will suffer the consequences”. Overall, this statement reflects the centralized leadership paradigm of China, which is different from the western social system in dealing with the crisis.

From the perspective of political communication strategy, this type of communication is a direct, authoritative and somewhat overwhelming. From a western point of view, it may even be considered as leading to a controversial way of maintaining the social orders during the pandemic. In his final passage, Xi Jinping called on the masses to strengthen their confidence, help each other in the same boat, prevent and fight the disease scientifically. Overall, this message is a common and popular slogan, in line with the government communication style and including the routine summary sentence formula of Chinese political leaders' four-point speech.

Moving to western political leaders, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson gave the first COVID-19 speech on March 3rd, later than other European countries such as Italy and France which had already some plans in place to control the pandemic. At the press conference, Boris Johnson laid out a four-stage system as the foundation of the emergency response plan as “contain, delay, research and mitigate”. Even though this slogan was changed many times over during the course of the pandemic, often creating mixed messages and confusion between the public, this message summarises well Boris Johnson’s attitude and communication style: the government is committed to making decisions based on the advice of world-leading scientific experts. Johnson also warned British people that COVID cases would increase and tried to convince the public to trust the National Health System (NHS) and the governmental testing program, albeit without a detailed description of specific initiatives and practices. Finally, he highlighted the importance to wash hands and trying to ease the panic between the public by reminding them of singing the happy birthday song while washing hands. The speech was clearly driven by medical and scientific expertise as can be inferred from the passage below:

“Some people compare it to seasonal flu. Alas, that is not right. Owing to the lack of immunity, this disease is more dangerous. It’s going to spread further, and I must level with you, level with the British public, many more families are going to lose loved ones before their time. The Chief Scientific Adviser will set out the best information we have on that in a moment. But as we’ve said over the last few weeks, we have a clear plan that we are now working through (Prime Minister’s office, 2020)”.

There is a sense that the prime minister's response is striking the right balance, issuing information that has avoided over-hyping the risk, and making proportionate responses to try to delay the spread of the virus that do not engender panic. That is not to say that the government’s response has been beyond reproach. When all the other countries and international scientific advice promote the way of ‘test, test, test’, it appeared that Britain was taking a different approach from other European countries to dealing with the virus, public confidence in the government’s strategy took a hit. Especially, a week after the public saw conflicting briefings coming out of Downing Street, fuelling public anxiety and leaving the prime minister looking as if he was out of his depth. In this crisis, in terms of Johnson’s personal style and his government’s combative approach to politics were poorly suited.

On the other hand, the Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte confirmed on January 30th that the first two cased of COVID had been detected in Rome, adding that the government had decided to close air traffic to and from China. “As far as we know we are the first country in the EU to adopt such a measure” Conte said (Reuters, 2020). Following on this first announcement, as cases kept rising in the northern part of the country, Conte held a press conference on February 9th, when a full quarantine was imposed across the entire country. He said:

“We are well aware of how difficult it is to change our habits, I am experiencing it myself, so I symphatise with all the families and the younger generations. But we have no time. We all need to give something up for Italy’s greater good, and when I say Italy, I mean all our acquaintances, parents and grandparents. We will succeed if we immediately get used to these strict rules. Let’s stay apart today to hug each other more warmly tomorrow” (Reuters, 2020).

What emerges from Conte’s words is a sense of personal sharing, sympathy and understanding. Conte’s empathy and personal commitment permeated his entire speech, for instance when he says: “I am experiencing it myself, so I symphatise with all the families and the youngsters”. He also calls for a shared feeling of unity by highlighting how Italy is made up of “all our acquaintances, parents and grandparents”. This is in stark constrast with Boris Johnson’s sharp and unsympathetic tone when he said, “families are going to lose loved ones before their time” (Prime Minister’s office, 2020). He also calls for a sense of national pride and shared purpose when he incites Italians to “give something up for Italy’s greater good”. Similarly, his message is warm, hopeful and friendly as highlighted by “Let’s stay apart today to hug each other more warmly tomorrow”. Finally, a feeling of urgency was also clear from expressions such as “We have no time” and “we will succeed if we immediately get used to these rules”, which highlights the preparedness and sense and gravity that hovered on Italy, as it was the first European country to face a significant spread of the disease outside of China.

4.2 The peak of the pandemic

On February 10th, President Jinping Xi presided a meeting on ‘Managing COVID-19: prevention and control'. The meeting consisted of three main parts. First, Jinping Xi presented a series of intervention he designed at the beginning of the outbreak in Wuhan; secondly, he discussed deployment work for the prevention and control of the pandemic, and finally, the recovery of the economy and industries affected by the lockdown were analysed.

In the first session, Jinping Xi defined the initial phase of the pandemic in Wuhan as "a war" and “Wuhan and Hubei” as the main battlefields in the fight against the COVID-19. In his own words: “The CPC Central Committee decisively imposed a lockdown in Wuhan on January 22nd. It took a great political courage to take the decision”. The second part highlighted Xi's previous work on managing the outbreak in Wuhan, while making several key points about strengthening international cooperation in the research and development of antiviral drugs and vaccines. He also called on people to abide by the social order and punish violations, and listening carefully to well-intentioned criticisms and suggestions. In the final part, Jinping made arrangements in advance for the possible impact on the economy. He believed that: “the impact of the pandemic is short-term and generally controllable”, as long as we turn pressure into confidence.

At this stage, Xi's speech is more detailed and comprehensive compared to his initial speech at the beginning of the outbreak. This second speech was longer and included an accurate use of numbers and strategic objectives. The layout of the initial interventions made the entire speech sounds like a self-report rather than an announcement of rules for the public to follow. In particular, Jinping xi used the pronoun "we" rather than 'you' or 'Chinese' which embodied that 'Xi stands between the Chinese people', similarly to Conte’s personal sharing in his previous speech.

This tone of speech continues on the previous Chinese political leaders’ tradition of "leading cadres should stand among the masses". Unlike western individualistic philosophies, “stand among the masses” is the product of a typical language mechanism in the context of socialism. Most importantly, in his speech, Xi defined the pandemic in Wuhan as a war and stressed that the decision of locking down Wuhan took great political courage. These words show political professionalism, especially the 'great political courage' reveals that the lockdown was not an easy political move to skillfully reply to the critics' argument that the lockdown amounted to a restriction of freedom. In fact, most of the countries worldwide followed suit on lockdown.

In terms of the continued measures on COVID-19, Xi supplement several points such as 'strengthen vaccine international cooperation' and 'thanks for all the support from other countries around the world'. It can be seen that Jinping Xi's governmental philosophy has always tended toward having and encompassing' bigger picture ' and the idea of establishing China's national image abroad. These ideas are implied in his entire speech. This has been interpreted by some media as "full of dominating world power ambition". However, in the context of the pandemic, this seems a genuine call for international cooperation to deal with the disease. This connotation is further explained by Xi when he states: "for well-intentioned criticisms and suggestions we should listen to, but to the voice of the malicious attacks to China we firmly disagree". Xi used the adjective 'seriously listen to' and 'firmly disagree’ to embody the attitude of the Chinese government. Finally, the prediction of a speedy recovery of the economy, reveals Xi’s confidence in China’s industry and ability to revive rapidly.

On the other hand, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson's response during the daily March press conferences became tough and practical. The pressure came mainly from rising COVID-19 cases in England and growing public unease. On 12th March Boris Johnson warned the country that, as a result of Covid-19, "families are going to lose loved ones before their time". Johnson might have been crudely realistic in his statement, but it seems unlikely that such statement would inspire courage and trust in the public. Four days later, on 16th March, his tone was far more urgent, as the prime minister requested everyone "to stop non-essential contact with others and to stop all unnecessary travel". Boris Johnson's would later be infected by the coronavirus, on 27th March, and spend seven nights in hospital, three of which in intensive care. His speech on his first day back at work was an attempt to provide reassurance that he was back at the helm of government. As he spoke outside Downing Street he touched on the lockdown, the economy and the health service's ability to cope. However, Johnson seemed to have missed the most critical moment throughout the fight against COVID-19 disease in April. In fact, his hospitalization at the height of the pandemic was unfortunate news. For the public, the diagnosis of a national leader means that during the time the country needs them the most, political leaders are incompetent to the position. During the time, the saga of rumours, denials and admissions took the nation on an emotional rollercoaster.

The performance of the British Prime Minister throughout the peak of the pandemic can be divided into two stages. In the initial stage, which lasted until the end of March, the outbreak in the UK was surging significantly and Boris Johnson’s response was a cold and stern response (recall the "families are going to lose loved ones before their time" statement). Compared with the leaders of China and Italy, the British Prime Minister used a more rational and scientific speaking style in his press conferences. The result may be to create a sense of uneasiness and uncertainty in the public and to further aggravate the panic among people. This is because the public might expect some promise from the government that guarantees the whole country to tide over the difficulties. Emotional and strategic communication styles are more useful to remit the panic emotion from the public. Good examples can be found in every America presidential election speech that how they stimulated public solidarity.

In the second phase of the peak of the epidemic in the UK, the Prime Minister missed some crucial developments because of its diagnosis of COVID. Although opinion polls showed an increase in the public support when he was diagnosed with the disease (Edelman, 2020), such an increase might not necessarily reflect a genuine higher degree of public trust in the leadership, rather a feeling of compassion for the Prime Minister being hospitalized. In fact, this compassion and empathy faded when unemployment arose, and the national lockdown prolonged in time. A series of lamentable gaffes and poorly prepared announcements have eroded public trust in the government's handling of the pandemic. In fact, there has been a growing clamour for answers about how Britain, two weeks behind the countries such as Italy and France in succumbing to the virus, wasted that crucial window of opportunity. Even though there was a scientific team behind the British prime minister to ensure that every speech made by the prime minister is accurate and justified, British people did not fully trust the government, as the polls show.

The peak of the pandemic crisis saw Italy in a rather difficult situation. Some hospitals in the northern part of the country were overwhelmed and many patients saw their treatments delayed. However, Conte’s communication strategy has always aimed at reassuring the population while keep projecting an image of competence and empathy. Surely the handling of the crisis has been far for faultless, but the Italian Prime Minister’s and his communication style have enjoyed a predominantly positive view (Edelman, 2020). Specifically, Conte held a formal press conference on April 10th to announce a further extension of the stringent lockdown measures. On this occasion, he said:

“We still need to keep vigilant. This is why we are taking a difficult but necessary decision, for which I of course take full political responsibility. It is a decision that I took after several meetings held with the team of Ministers, with the experts of our technical-scientific committee, with the Regions, the Provinces and the Municipalities, with the trade unions, the world of business, industry and with trade associations (Reuters, 2020)”.

It emerges from his speech that Conte wanted to appear competent and inclusive by listing all the parts involved in the decision to extend the lockdown measures. He also announced the establishment of a new committee to support the governmental decisions, made up of world-leading experts in the fields of epidemiology, social policies and mental well-being. This move was clearly aimed at reassuring the public while highlighting that all the decisions taken by the government were guided by science. Overall, this press conference represented another good example of Conte’s technical but sympathetic and benevolent communication that earned him high approval ratings during the pandemic.

The factors impacting on public trust

Based on the discussion above, public trust is vitally important to ensure both stable leadership and cohesion of the public. Especially in the context of the pandemic, a high level of public trust is crucial for ensuring full public compliance with the rules formulated by the government. As Llewellyn (2020) argues very clearly: “in times of crisis, trust is the most important thing to consider if you want to communicate health advice.” The author suggests that increasing the public’s sense of control should be part of future policy. Building trust with the public should be a core theme of every government’s ongoing pandemic strategy, particularly as we look at easing lockdown restrictions and returning to some form of normality. The public needs to trust in the government being sensitive to the fears and anxieties that people are experiencing, and that the government can put in place the right strategy to respond. The public needs to perceive that some institutions can do something about the pandemic and protect them. This argument is bilateral, because, at the same time, the government needs to trust the public to be compliant and then implement the next phases of their plans.

Accordingly, UK insisted that its actions were all being “led by science”, a phrase that the British public has become accustomed to hearing from Boris Johnson’s press conferences. However, the “led by the science” rhetoric has not been without criticism. In fact, the relationship between public trust and science in the UK has been historically weak. For instance, in 2019, the NHS Health Research Authority (HRA) launched the “Make it Public” campaign with the aim of “enhancing public trust in research evidence and enhancing public accountability.” Hence, scientific uncertainty regularly results in political manipulation and debates about communicating complicated models to the public. Scientific models, in particular, are frequent subjects of political contestation, as in the case of climate change, because of their inherent uncertain. COVID-19, as a novel coronavirus, is defined by uncertainty. This is perhaps most readily apparent in models predicting the virus’ spread, which have been plagued by limited data and the emerging scientific assumptions about transmission and public health interventions.

As a result, the “led by the science” approach has not enjoyed widespread approval in the UK, as showed by recent opinion polls that reported a significant fall in public trust in the UK’s handling of the pandemic (Edelman, 2020). This is worrying; because doubts and a loss of confidence during an outbreak may influence public behavioral responses. Falling opinion polls may not be the only negative consequences to consider. Despite reporting adherence to social distancing measures, people may be reporting a loss of meaning and self-worth. Therefore, in this context, strategic communication and tougher leadership are key factors in winning public trust as well as ease public mistrust of scientific communication. To deal with the immediate crisis, public administration needs to explore institutional reforms that focus on more leadership and sincere communication (Meier, 1997) in public health while emphasizing the importance of transparency, compassion, empathy, and evidence.

On the other hand, the Italian government, even though not exempt from critics of mishandling some aspects of the pandemic, enjoyed a more positive response from the public in terms of trust throughout the health crisis. It is worth noting here that the high levels of trust experienced by Conte’s government during the pandemic are in contrast with the relatively low levels of institutional trust characteristic of Italy, both historically and in recent surveys. In fact, the Italian public has historically shown a widespread attitude of distrust towards the same public authorities that it now needs to rely on (Falcone, 2020). This phenomenon of increased trust can be partly explained by the charisma and communication style of Conte, which gained him high approval rating, as well as the need from the public for a public authority to trust. A pandemic like COVID-19, caused by an unknown illness for which there is no cure, inevitably generates anxiety and fear and, as a result, the need for a public authority to trust. The Italian public did feel this need, and Conte represented the perfect face and personality to rely upon, thanks to his calm, emphatic and personable communication style.

Finally, polls from May 2020 revealed that the public trust in the Chinese government during the pandemic as risen to 95 percent, which is up 5 points from the last survey in January, giving the country its top ranking among the surveyed countries (Edelman, 2020). Such a high-scoring level of trust in the government may seem unconventional in Western systems, but by analyzing the socio-cultural background of China, along with Jinping Xi's speeches, I find that there is a strong basis for public trust in the Chinese government from Chinese people.

First of all, China was the first country in the world to experience the COVID-19 outbreak and, at least in the initial stages, it was more serious compared other countries because of relative unpreparedness. Because of being faced with an aggressive disease without prior knowledge of or cure for it, Chinese leaders acted relatively late than expected, despite appearing in front of the public. This evidence also can be found with political leaders in Italy and the UK, who have appeared on press conferences when there were already several confirmed cases in their respective countries. As Jinping Xi's first appeared at a governmental meeting, Chinese-style propaganda tactics spread among the public. By searching comments on the NetEase's news app, I found that most of the messages from the public tended to support the government's decisions. Such messages included "Don't cause trouble to President Xi", "Let's build a great China", "We will win this war" and "come on, strong people of Wuhan, we all support you". At the same time, I tracked some negative views about the lack of transparency in some of the data, statements from the local governments and complaints about the slow reaction of the Wuhan local government. I noticed that these remarks were mainly directed at local governments. In order to support this inference, I contacted people who were critical of the local government.

On the one hand, interviewees believe that in the early stage, the local government in Wuhan ignored the severity of the virus. This led to a lot of rumors around the source of the virus at the end of January, causing anger and distrust in local officials. On the other hand, the interviewees greatly approved the central government action aimed at correcting the idleness and inaction of local officials. In other words, they praised the central government for its leadership in mobilizing other local governments to support Wuhan. This trend generally fits with Xi Jinping policies. In fact, since he took office, he has been severely punishing local government officials for inaction and corruption, which led to increased public trust in the central government as an effective and practical government.

However, it might also be argued that authoritarian blindness, which has been the perennial problem of the Chinese system, with its centralized, top-down administration has now showed again. Such authoritarian blindness may lead to a decline in public trust in future. This is because instead of openly reporting massive failures, the local governments always report ever-increasing surpluses and positive news, both because they are afraid of reporting bad news and because they want to please their superiors. Despite this chronic issue of the Chinese political and administrative system, China seems to have dealt with the health crisis comparatively better than other countries, for instance by avoiding a second wave of infections (at least at present) and containing the number of deaths to relatively low numbers.

Nevertheless, whether COVID-19 proves the superiority of Chinese authoritarianism can only be judged by the containment degree of the coronavirus in the long term. What seems plausible at this stage is the link between trust in the government and success in containing the virus. If citizens trust the state, they will see its directives as reasonable, worth following and will comply with the regulations. To this end, the Chinese authoritarian political systems achieved greater legitimacy than liberal democratic counterparts. In modern China, the authoritarian political system is understood differently from the common western conception of "authoritarianism", as it is inextricably blended with the key Confucian concept of social harmony. According to the principles of Confucianism, a society is effective when power and authority are organized hierarchically. In such a hierarchy, the rulers and the government are viewed as a paternalistic authority that endeavors to ensure the well-being and unity of the common people. In return, the task of each individual is to fulfill their duties by faithfully following directives (Ng, 2000).

The result of this legitimacy and loyalty is that citizens' trust in leaders increases and public health crises are handled more effectively. In addition, years of grass-roots political experience has enabled Xi to mobilize public confidence, strength and emotion in its speech on the fight against the epidemic. What seems less clear, however, is a correlation between efficacy of the containment measures and regime type. While some autocracies have contained the virus to relatively low level, like Singapore, others have done very poorly, like Iran. Similarly, some democracies have stumbled, like the UK, the United States and many other European countries are experiencing a second wave of infections, while others have performed admirably, like South Korea and Taiwan.

Discussion and conclusion

From the start of the pandemic, it has been clear that this was going to be more than just a public health crisis. At the heart of the pandemic and its implications has been the question of public trust, the relationship between consent and authority, self-interest and solidarity. By comparing Jinping Xi, Giuseppe Conte and Boris Johnson's speeches throughout the pandemic, I found out what people want from their politicians are strong and feasible promises from the central government and a call for unity and confidence to fight against the virus.

We have referred to the definition of 'authentic communication' in the literature review section. A review of the speeches of political leaders reveals that these politicians have tried to adopt an authentic style of communication. However, the levels of success in gaining public trust have been different according to their respective political system, cultural background and policies. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson's style tends to be objective, scientific, based on hard evidence and advocating for practical measures. However, this strategy has not been ideal, as the levels of public trust dropped during the crisis. Italian Prime minister adopted a more personable approach and projected an image of competence, empathy, reassurance, and personal sharing. These qualities resulted in an increased trust from the Italian public which sharply contrasts with the historical trend of distrust in Italian institutions. Jinping Xi's speeches are sincere and call for unity, while being permeated by a tone of authority. As a result, Chinese citizens’ approval of the government has reached much higher levels compared to the western counterparts.

As COVID-19 threatens the health of communities across the globe, the success of governmental measures depends largely on the levels of compliance, which will in turn depend on the confidence that citizens have in their leaders. In this circumstance, it is necessary to delivery strategic and authentic speeches and information to the public. A combination of strategic and authentic communication seems to be inevitably needed to deal with a public health crisis. However, the extent to which this combination needs to be applied depends on the societal system and political environment.

In this sense, President Xi did not need to use a very strong warning tone or to explicitly exhort the public to abide by the rules, since authoritarianism has been the principle pursued by China's ruling party and Chinese citizens trust their government as being effective and resolute. Instead, the spirit of the President’s speeches is more caring and inspiring. On the contrary, in the UK, a country founded on deep ideals of liberal democracy, the Prime Minister has tried to convey a rational and scientific voice in the face of the crisis. However, the public did not fully trust and abide by the statement of the British government and the scientists' team. This may be because the attitude conveyed by Boris Johnson in his speeches is not a strong and firm one; Johnson’s point of view always sounded more like a scientific suggestion, rather than an effective way to curb the spread of the disease. In addition, the British Prime Minister did not "stand among the masses" in the course of the health crisis, which can be seen from the separation of the concepts of government, NHS and the British people in Boris Johnson's speeches. Finally, Boris's absence from the press conferences in April, which was at the peak of the pandemic in the UK, has largely dampened public trust in the government.

On the contrary, Chinese citizens mostly praised the strength and effectiveness of Jinping Xi in dealing with disease. However, this does not mean that the satisfaction between the local government and central government is consistent. The public trust in the central government is related to the satisfaction of local residents, who have often criticized local government for inaction and downplaying the severity of the virus. Chinese political leaders should re-consider the power dynamic between central and local government and take these points into account in order to strengthen future speeches.

In the case of Italy, the image of competence and personal sharing created by Conte largely earned the trust of Italian citizens and earned him approval. Even though the actions of the Italian government have not been spared from critics, the public trust in Conte’s government has been high, especially considering that Italy has recently been affected by a progressive erosion of trust in public institutions and a general state of information crisis regarding matters of health and science (Lovari, 2020). However, a savvy use communication channels, such as social media, combined with his personality, have helped Conte project a very positive image of himself and earn trust.

In conclusion, a leader’s response to a crisis is much more than speeches. Surely, the ways of communication play a key role in obtaining the public’s trust and co-operation. However, political leaders also face the monumental task of reassuring the public and persuading them to follow through on government decisions. This article showed that achieving collective compliance and trust is not trivial because the negotiation between the government and its citizens depends on the different social system, circumstances and particular situation in different countries. In this case, every country is a different case. In Asia, especially in China and Japan, there has always been a historical habit of wearing face masks. This habit stems from paying special attention to respiratory health problems (Fillmore, 2018), protecting from smog or avoiding breathing in cold air. This cultural habit has surely made it easier for the Chinese central government to achieve compliance from the public compared than in the other two countries. Conversely, mask wearing has been met with skepticism and hesitation by the general public in UK and Italy, at least during the initial stages of the pandemic. The deeper reason for such differences is that in Western democracies plurality and freedom have been at odds with the restrictive measures imposed by the governments. This apparent incompatibility has been tackled with very different strategies in the UK and Italy, and it seems fair to state that the friendly and sharing manners of Giuseppe Conte have proved more effective than the cold, scientific and fact-driven strategy of Boris Johnson in terms of earning public trust. However, in China, while the government had to deal with the chronic problem of authoritarianism blindness as well as international critics, the sincere but firm and resolute tones adopted by Xi Jinping ensured an even higher level of trust in the government compared to the beginning of the pandemic.