Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

On-line version ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.11 Braga June 2023 Epub July 30, 2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.4512

Thematic Articles

The Laws of Attention-Capturing. Reflections on the Role of Video in Digital Platforms

i Centro de Investigação em Comunicações Aplicadas, Cultura e Novas Tecnologias, Faculdade de Comunicação, Arquitetura, Artes e Tecnologias da Informação, Universidade Lusófona, Porto, Portugal

ii Faculdade de Comunicação, Arquitetura, Artes e Tecnologias da Informação, Universidade Lusófona, Porto, Portugal

A imagem é um dos suportes dominantes na comunicação contemporânea (Martins, 2021, p. 185). A convergência cultural atual faz-se, sobretudo, em torno de imagens digitais (Jenkins, 2006/2009). Nesta premissa, o vídeo é um dos tipos que mais destaque alcançam na era da imagem e dos ecrãs (Costa, 2012; Loureiro, 2011; Martins, 2011).

Diferentes empresas de comunicação digital, através de diferentes plataformas, utilizam arquiteturas e algoritmos com diferentes técnicas e métodos nos modos como usam a imagem para comunicar e capturar a atenção. O meio digital é pensado tendo como elemento central imagens para comunicar e leis algorítmicas para reter e fidelizar os cidadãos (Lanier, 2010/2010, 2018/2018).

Teóricos da economia da atenção entendem que as empresas que gerem as grandes plataformas digitais têm um grande objetivo: capturar a atenção das massas de

modo a criar fidelização e retenção nos consumidores/utilizadores (Martens, 2016; Srnicek, 2017). A economia da atenção é um dos seus principais setores, tendo como um dos negócios primordiais a ecranovisão (Costa, 2014). O pagamento do sujeito às empresas que gerem as plataformas digitais é feito por intermédio de um constante dar visualizações (Costa, 2020b), de uma persistente telepresença, de uma frenética partilha de conteúdos, de uma utilização corrente dos inúmeros serviços e ecossistemas digitais. É a soma de muitos a ver, a tele-estar, a tele-partilhar e a tele-usar que permite dinamizar a economia da atenção.

As grandes empresas digitais lutam pelas fatias maiores dessa economia. Os que mais utilizadores fidelizam e retêm são os que mais lucram. A estratégia maior reside nos métodos e nas técnicas de captura da atenção utilizados. Essa cria “leis”, quer dizer, regularidades e padrões que se movimentam entre diferentes empresas e diferentes dinâmicas sociotécnicas. O vídeo, enquanto método e técnica de captura da atenção, utiliza “leis” e trilhos, contribuindo para posteriores processos sociais de uso, influência, manipulação, imitação, propagação, socialização e individuação. Neste artigo, tentamos dar conta de algumas regularidades e padrões gerais utilizados no vídeo para captura da atenção das massas.

Palavras-chave: vídeo; leis; captura da atenção; plataformas digitais

Image is one of the dominant media in contemporary communication (Martins, 2021, p. 185). The current cultural convergence is mostly about digital images (Jenkins, 2006/2009). Based on this premise, video is one of the most prominent types in the era of image and screens (Costa, 2012; Loureiro, 2011; Martins, 2011).

Different digital communication companies, based on different platforms, use different architectures and algorithms, with different techniques and methods, to use the image to communicate and capture attention. Digital media is planned with images as a central element to communicate and algorithmic laws to retain and build loyalty among citizens (Lanier, 2010/2010, 2018/2018). Theorists of the economy of attention argue that the companies managing the major digital platforms have one main objective: to capture the attention of the masses to create loyalty and retention of consumers/users (Martens, 2016; Srnicek, 2017). The economy of attention is one of their main sectors of activity, with screen vision as one of its core businesses (Costa, 2014). The individuals' payoff to the companies that manage the digital platforms is made through constantly giving views (Costa, 2020b), persistent telepresence, a frenetic sharing of content, and the current use of the numerous services and digital ecosystems. The sum of many watching, tele-being, tele-sharing and tele-using allows for dynamising the attention economy.

The big digital companies are fighting for the biggest cuts in this economy. Those with the highest user loyalty and retention are profiting the most. The key strategy lies in the methods and techniques used to capture attention. This strategy creates "laws", that is, regularities and patterns that flow between different companies and different sociotechnical dynamics. The video, as a method and technique of attention-capturing, uses its "laws" and tracks, thus contributing to other social processes of use, influence, manipulation, imitation, propagation, socialisation and individuation. In this article, we seek to account for some general regularities and patterns used in the video to capture the attention of the masses.

Keywords: video; laws; attention capture; digital platforms

1. Introduction

According to Bruno Patino (2019), capturing attention has become a science: captology. A science that drives a market within contemporary informational capitalism and that is organised fundamentally around digital platforms (Srnicek, 2017).

Martens (2016) argues that the logic of platformisation survives because it comprises a financially advanced captology. Namely: platforms that are remunerated by "advertising" (Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, etc.); platforms that are intended to directly "bring together" buyers and sellers (Amazon, eBay, etc.); and platforms that "facilitate" financial transactions (PayPal, MB Way, etc.).

To "advertise", "bring together", or "facilitate", digital platforms first need to capture attention and then change and shape behaviour according to financial rather than social objectives - hence the idea of the "social dilemma" (Lanier, 2018/2018). The metaphor of the hive, fully interconnected and controlled, confronts or interlinks powers between government institutions and high-tech companies, tailoring behaviours to suit premeditated interests (Zuboff, 2019/2020).

From a social perspective, there is concurrently a web of uses and gratifications granted by these platforms, making the everyday experience resemble a roleplaying game experience. The user, friend, professional, son, father, student, consumer, citizen of a given nationality, and fan of a music band or a football club or player, among several other roles, is summoned by these to respond to multiple stimuli on issues that the respective algorithms have detected as important to the individual.

Jemielniak (2020) believes that the major digital platforms are, broadly speaking, powerful multiplayer online games, widely popular. From Facebook to Twitter to TikTok, Wikipedia or Instagram, there is a social movement, in the form of a game, that constructs meanings and propagates information, develops pro-social behaviours, moral dualisms, political struggles, social tensions and prejudices (Reagle, 2010; Rijshouwer, 2019; Tkacz, 2015). As such, the participants of this role-playing game have a facilitating role in this everyday game, imitating, counter-imitating and replicating play and social competition logics in various mundane schemes.

Considering the above, and based on Gabriel Tarde's (1890/1978; Costa, 2021c) "laws of imitation", we ask: with the advent of screens connected by digital networks, where video stands out as a means of communication, are we not facing a global movement of diffusion, through video, of forms that imitate processes aimed at capturing attention? To answer this question, we outline the thesis that these dynamics form, within digital platforms, a set of "laws" repeated and imitated with some nuances, that is, active and passive sociological structures that flow into forms of attention capture. There are "laws" of general scope that generally apply to digital platforms, such as active and passive algorithmic schemes. However, the video also holds "laws" since its genesis, and different platforms have some particular "laws". Such is the dynamic we want to address in this text, announcing and describing these "laws" openly and not exhaustively as one of the major elements influencing the current digital culture.

Moreover, it is also worth noting that a contemporary way of demonstrating the new individuations, socially exposing them, has been achieved through digital platforms. The individual, once more incognito and less exposed, now has the social possibility of revealing himself on all subjects through social-digital platforms. The demonstration of a more inner, more subjective self, less covered by the external persona (Jung, 1928/1969), now happens publicly, often without filters and flowing through cyborg perceptions and representations, things halfway between the human and the machine, which the human-machine interaction ultimately brings to the world (Martins, 2011; Miranda, 2008). The persona, that complex system of relations between the individual's consciousness and society, now leaves like some of the comforts of the home, the computer desk or the pocket mobile phone to henceforth expose the most unlikely individuations (Neves & Costa, 2020).

This mode of exposing individuation is possible by observing reactions in individuals' interactions within socio-digital platforms. The consumption of a video and the consequent type of reaction, even if limited to small written comments or simple emotional emojis, shows much about the individuation of contemporary subjects on numerous aspects and how these then echo in comments, opinions, imitations, emotions, socialisations (Costa et al., 2022).

However, just as each one of us can observe the reaction of numerous individuals to various types of content, digital companies and their algorithms also monitor behaviours and individuations, perceiving, sometimes rationally and sometimes emotionally, what are individuals more sensitive, more reactive and more easily manipulated so that retention and loyalty are more efficient. That is the major success of digital platforms overall and one of the main means of creating strategies and laws in the art and science of attention-capturing (Costa, 2021a). To the thesis that the West is founded on the word, it is complementary to suggest the screen as the producer of new individuation, the reason for translocation from the culture of the word to the culture of the image (Costa, 2014, 2021a; Lipovetsky & Serroy, 2007/2010; Loureiro, 2011; Martins, 2011). With cinema and television, the initial effect was visual-imagery mass-media, compared with visual-written mass-media. Both embedded the idea of the media as a message (McLuhan, 1964/2007). However, with the development of the internet, other sociotechnical possibilities generated greater customisation (in consumption, production and habits), reaching prolific self-media dynamics and a customized quantum of the human-machine mixture (Kerckhove, 1995/1997).

This apparently subtle nuance summons us to an observation Norbert Elias made in 1939 in O Processo Civilizador (The Civilizing Process; 1939/1993): in the transition from one predominant organisation to another, "which embraces more people, and which is more complex and differentiated, the position of individual men is transformed in its own way towards the social unit they form together" (Elias, 1939/1993, p. 198). This shift is "accompanied by another pattern of individuation" (p. 198).

Capturing attention in the current pattern of individuation is, therefore, to capture emotions, reasons, motivations, desires, imitations, tastes and everything that provides individuals' adherence to things. The methods and techniques used are not restricted to algorithms, the most recent and perhaps most widely used technique, since images, in general, and video, in particular, has come a long way in constructing meanings, perceptions and representations. The innovation here, vis-a-vis the relationship between video and digital platforms, is that, unlike, for example, any television advertisement shown in the intermission of a programme or film we watch, there is the advantage of the image-movement appearing through algorithms for collecting emotions, tastes and preferences. The company knows it will be more efficient in generating retention and loyalty in the viewer. In other words, algorithmic techniques are used to identify the trends, habits of screen use and digital networks, profile, history, and everything required for a maximised display before the eyes of the individual. In this way, the algorithmic science of captology is ubiquitous in digital, at the service of the financial profit of the big platforms (Patino, 2019). This constant collection and dropping of information about the individual chosen by the algorithm epitomise an unprecedented dynamic. Showing what the individual "wants" or "likes" and hiding what is not in their interests, preferences, and motivations can force encounters between clusters of people with close or similar preferences. Byung Chul Han (2018/2018) called this process "the expulsion of the other", the expulsion of the one who is different, who lives and thinks differently (Costa, 2021b). If we want to use a more optimistic logic, we can call it the approximation of the same: the other equal to me, who thinks like me, who likes what I like. For Han (2018/2018), this always leads to a depletion of experience since it reduces it to the consensual part of life. Are we not, with this dynamic, facing a puissant social positivity?

Moreover, as the machine seizes and knows me, an effect of repetition, of similarity, is generated, standardising tastes and then allowing the creative human, the one who builds the video and the contents, to segment their market. This corporate mode of placing individuals in clusters demonstrates the strong monetary essence of social-digital platforms, which are nothing more than companies seeking profit within a broader economy but driven by the force of attention. We will reflect on this purpose, questioning the laws of attention-capturing.

2. Types of Attention-Capturing in Digital Platforms

At the end of the 19th century, Gabriel Tarde (1901/1992), in A Opinião e as Massas (The Opinion and the Crowd), proposed a reflection on the masses and how someone who extracts their thought visually through one writing on newsprint could capture the attention from a distance, while triggering a whole chain of similar ideas and opinions, both in conformity and opposition. In As Leis da Imitação (The Laws of Imitation; Tarde, 1890/1978), this reflection was even more audacious, proposing a sociology according to the understanding of personal and interpersonal imitations with the visual sense also as a conductor of imitations, sometimes for logical, sometimes for extra-logical reasons. He believed these imitations generated inter-mental and intersubjective associations and dissociations with a propensity to reproduce and renew through imitation or counter-imitation and innovate through differentiation (Costa, 2021c; Deleuze, 1968/2000; Latour, 2012; Tarde, 1890/1978, 1901/1992).

By analogy, something similar happens in the era of digital platforms but within a more accelerated and efficient process. A video or an online news item circulates faster than in the past, reaches the addressee with greater criteria, and becomes liable to the construction of meanings and representations with greater efficiency. That is because what is given to look at will capture what the individual's subjectivity will have already placed in the algorithms upstream.

We believe digital platforms also contain the three elements that Simmel (1950) deemed essential for social structuring. The three confronting elements are the individuals, the objects (contents) and a third element (those on the digital platform) that coerces and supervises. For Simmel (1950), when cast upon the other two related elements, the eye of the supervising element would surface as a trigger of force and capture of the moment, posing a foreign supervision over the social conduct of the related elements. With the triad, there is "a balance between positive and negative forces, especially between conflict and cooperation. It is in the three-way games that sociology really begins" (Higgins & Ribeiro, 2018, pp. 22-23).

A privilege of contemporaneity, vision is now accelerated by a wide set of ocular and mass teletechnologies converging (Jenkins, 2006/2009) to increase the capacity to capture attention at a distance, creating and mobilising meanings, representations, expressions and unprecedented relation and association modes. Eye technologies emerge as one of the main pillars, although not the only one, in creating social atmospheres and contingent intellects (Costa, 2020b, 2021c).

Here Bruno Patino (2019) proposes the thesis that there is an acceleration, mobilisation and gamification forced by captology. A problem that no longer has to do only with mass production and is related to a logic of surveillance and sociotechnical response to stimuli that can modify and shape behaviours. Instead of exploited workers, millions of people are harnessed to convey goods in a digital environment (Crawford, 2015; Davenport & Beck, 2001; Patino, 2019). Capturing strategies, such as the slot machine effect, stemming from F. Skinner's behavioural experiments on rats, which are famous in casino games, are now invitations to random and diverse rewards in the apparent simple gesture of scrolling down the feed of digital platforms. Examples are Facebook (Costa, 2020b; Patino, 2019) or the Zeigarnik effect. It derives from a set of connected actions that must chain together continuously, as in the case of TikTok, generating incompleteness and a subtle dosage of satisfactions and frustrations (Zagalo, 2012), or even the sentinel sleeper effect, generated by the anxiety of waiting for audible, vibrating or colourful notifications that affect sleep, mood and concentration (Eisenstein & Estefanon, 2011). These are just a few examples of acceleration, mobilisation and gamification that captology techniques operate in the digital environment with great effectiveness in the retention and loyalty of user-consumers.

These effects, to which we can add the fear of solitary consumption, a fear of missing out on the content currently being consumed on YouTube (Costa & Capoano, 2020), or the anxiety syndrome, a permanent need to display the different moments of one's existence, through photos, videos or descriptions, receiving gratification through comments or likes (Lagrange, 2020), or even athazagoraphobia, fear of being forgotten by peers when a compulsive search for a like, a share, a comment or a mention (Anderson, 2013), among others, are related to various personal and/or collective events and happenings. To illustrate this, we should remember that Facebook was flooded with audiovisual proof of vaccination at a certain point during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was a way of showing that you belong to the group of those who believe in science, but also to escape from loneliness and hesitation of choices, to dispel anxiety about your position in your social network or to have an excuse for yet another post and consequent gratifications in the form of likes in line with the dominant contingent intellects. Does this social need to belong not reflect a fear of social loneliness?

Considering these aspects, we examine some examples of these capturing dynamics in different digital platforms, which differ according to the technical means used and the existing digital architectures. Let us consider the same example on different digital platforms.

2.1. Facebook

When the Football World Cup took place in Qatar, any previous followers of the sports newspapers' Facebook pages would have been overwhelmed by the power of EdgeRank (Facebook's algorithm). That algorithm loaded the feed with multiple highlights and news stories of that sporting event. For sports journalists and newspaper managers, the men's World Cup event was more interesting from the standpoint of interest and attention than any discussion about ethics or human rights compliance in Qatar. That is because the events of the boiling moment capture more attention than any theoretical discussion about a host country's laws. Minute after minute, hour after hour, news about the World Cup erupted through Facebook users' viewing frames on their feeds. For someone who already followed digital sports newspapers, the World Cup event became the most attention-dominant event of its users from November 20 to December 18, 2022.

One of the moments of the event that circulated the most on Portuguese Facebook at that time was, precisely, the moment when Cristiano Ronaldo tried to head the ball to the goal, which was ultimately credited to teammate Bruno Fernandes (Figure 1).

However, an important aspect to consider on Facebook is: that the attention-capturing through EdgeRank differs from other platforms with other algorithms. On Facebook, this moment, for example, represents a type of attention-capturing that includes "video of the moment", "news", and "public comments/conversations". Thus, in simplistic terms, we can classify Facebook as a digital platform where video emerges as the support of the moment to work as a trigger (Costa, 2020a) of conversations, comments, reactions and shares. The attention captured is of the kind of moment turned into news and immediate public discussion.

That is what happened in this case: the video of the goal worked as a trigger of conversations, comments, reactions and shares. Those who idolised Cristiano Ronaldo wrote things in its favour; those who hated Cristiano Ronaldo wrote things against it; and others, perhaps more neutral and disinterested, watched the topic unfold. The moment became open news and the stage for countless heated conversations. As a record of moments, the emotion of the moment and video is one of the factors of temptation and loyalty in placing communities around common elements. As Han (2018/2018) would say, amid the whirlwind of events and in a time where it is easy to create dualisms and binomials, what is different will be easily rejected and what is equal easily confirmed with the sociotechnical permissions of digital networks' customisation.

2.2. Instagram

On Instagram, the algorithm is slightly different. It mainly shows the most personal images from the individual's network with the most reactions. Moreover, its network is different because the algorithm's layout is different. Instagram's structure is set up for us to follow mostly individual personalities (and not so much collective ones) and images. The link to the outside, such as a news site, does not exist enticingly (it only appears in the text). When following a person/personality/institution, text summons me to stay on the platform, to the event and to the existing likes from the people in my network. The comments, for example, are numbered but with little prominence.

Let us go back to Cristiano Ronaldo's near header moment: in this network, it was not so much about whether Cristiano Ronaldo touched the ball or not, in words. It was mainly the image showing the moment, not as much as a news item but as a moment turned into imagery art. On this platform, the online newspaper institution almost disappears, leaving the moment stripped of the institutionalisation of subjects and customised by the network element that shares it. Thus, unlike Facebook, where the newspaper, the channel or the TV page enters the feed with the moment and gives us access to their pages, on Instagram, the capture of attention is rather on someone personal in my network, therefore someone non-institutional, and the moment in the form of a photograph or video (reels; Figure 2).

Figure 2 Montage to demonstrate the achievements or shortcomings of the Portuguese national team's performance at the World Cup in Qatar

In this sense, we can classify Instagram as a digital platform where the video is a second version, something already processed, edited and subjectively customised by someone, to be a trigger, not so much of conversations or comments but rather of instant reactions and shares. The attention captured is of the kind of moment turned into the subjectivity of another to conquer reactions that ensure visibility to that who customises and propagates.

2.3. TikTok

On TikTok, everything is very different from the previous ones. Still, more different from Facebook than from Instagram. On the same subject, what prevailed on this platform were short videos, of little more than 15 seconds, about this event. In this case, the videos were not those of Cristiano Ronaldo almost touching the ball but rather of someone reproducing a simulated moment to show what happened (Figure 3). The capture strategy is different, but the digital montage, the tragedy of imitation with a joke, or the montage in the form of parody on Ronaldo's claiming of the goal are some of the most common examples on this digital platform (Grados & Gabriela, 2020). The fact that this network is composed of a young generation introduces, among other differentiating elements, the following: speed in video transition, the climax of the event in a few seconds, and simultaneous fun or tragedy. If the user reacts positively to the corresponding video, the algorithm gives other ways of representing the moment on video. Almost without letting the user breathe, the videos follow each other constantly on topics to which the user has reacted positively, thus creating a pattern of attention. Such a pattern is built by the different reactions to different types of video (whether the user likes the funniest, the most tragic, emotional, or violent, etc.). Here, what captures me is my subjectivity in 15 seconds of video on one or more topics. That is, the type of capture is focused on the individual, the things he or she most likes to see, and is turned into a 15-second video.

2.4. YouTube

YouTube has two ways of capturing attention: either through short videos; or by the suggestions of videos by topic (music bands, animes, movies and movie premieres, video games, football plays, etc.). The algorithm suggests videos describing the user's personal history, from the most watched to the least watched. Going back to the football topic: on this network, it will not be Cristiano Ronaldo trying to head the ball at that moment, but some compilation of his best moments playing football and preferably with music playing (Figure 4). YouTube's algorithm preferentially merges visuals with audio - since part of its success is music playlists. So, if we access a Cristiano Ronaldo video, a few more will be suggested about his performance, interspersed every five by videos that the user has already viewed several times (usually on other subjects to enable retention through diversity). In other words, on this digital platform, the individual's preferences are those focused on longer videos. The attention is captured because the user already has a profile generated by the algorithm (GoogleRank), and there is a strong sound dynamic to make retention and loyalty. We can classify YouTube as a digital platform that captures attention by using video to capture visual and audio subjectivity simultaneously.

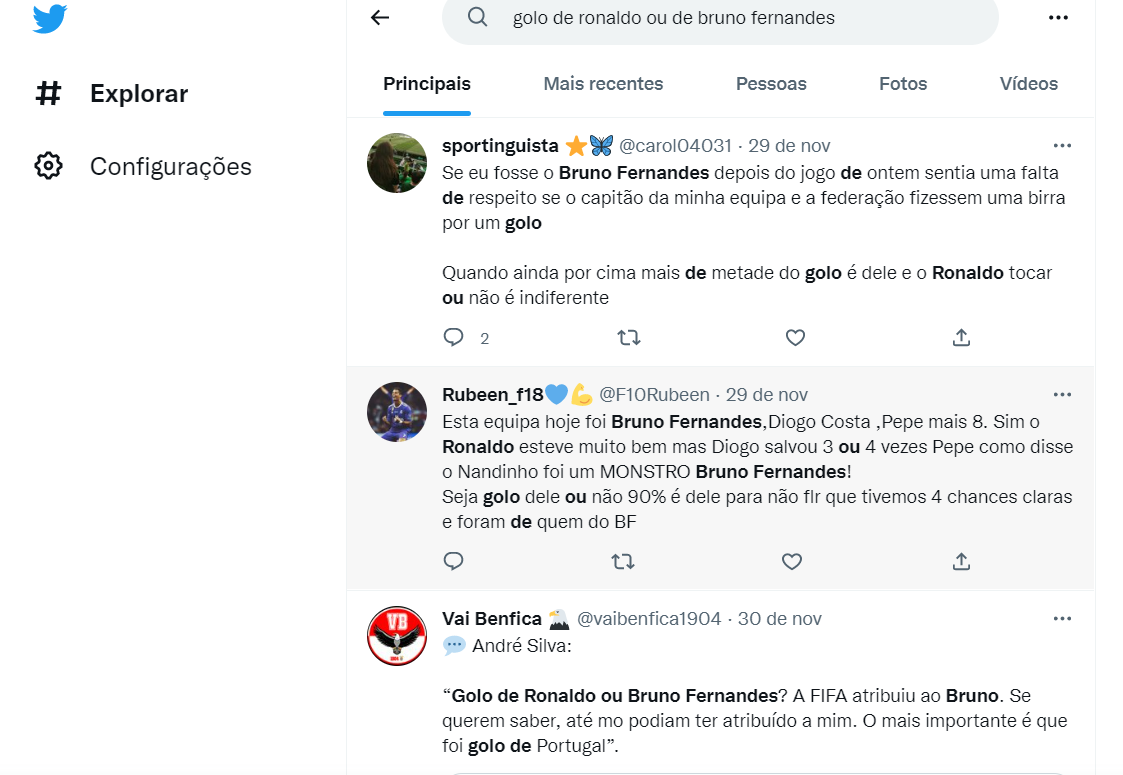

2.5. Twitter

Twitter is down to the individual in a comment or opinion mode. The opinions pop up in the feed through other people or personalities. Taking the football example again, we will get a personality we follow, drawing comments about the World Cup or a particular match or moment of that event (Figure 5). Here, the emphasis is on people's opinions, which the individual follows, and will capture his or her attention. That is, among the various comments that are followed, the algorithm will favour and highlight those that obtain greater numerical repercussions (shares, reactions, etc.). Twitter shows a greater preponderance in the rationalised-opinative attention of the individual's life. In this social network, the attention captured is the individual's opinion historically recorded in the algorithm, or its opposite, to lead it to retweet or discussion.

Image retrieved from https://twitter.com/search?q=golo%20de%20ronal do%20ou%20de%20bruno%20fernandes&src=typed_query

Figure 5 Excerpt of the commentary on the goal situation

2.6. Wikipedia

Wikipedia is here, purposely, a nuance vis-à-vis all previous digital platforms. It is a different platform in objectives and priorities because it aims neither for profit nor to retain people's loyalty. It is the dissemination of its content, of written and encyclopaedic scope, that matters, even if it is also subject to contingencies (Costa, 2021b; Costa et al., 2021). During the pandemic, its most visited page was the daily counts of dead/infected with COVID-19. In the World Cup 2022 period, it was content about players, teams or track records/scores in World Cups. The focus is on the content's accuracy, depending on external sources, which will serve not so much the moment itself but the moment's posterity. For example, about football World Cups: if there are doubts about who has won more World Cups; when; with which teams; etc. Wikipedia is a safe place to check this kind of information. Here the type of attention-capturing is for posterity and curiosity about the knowledge recorded. The place of the video is non-existent. The case of Cristiano Ronaldo's video almost touching the ball is not even in their database because it is not a recorded fact in his favour.

3. The Laws of Digital Attention-Capturing

Despite the different types of capture according to the different digital platforms, like the examples we suggested above, there are general laws in all types of capture. Each previous example was only to demonstrate, in simple terms, the existence of specificities between digital media and the different strategies and types of capture used. Nevertheless, each digital platform is permeated by what we call attention-capturing laws. Inspired by Gabriel Tarde (1890/1978), we divide these laws into two topics: logical laws and non-logical laws of attention-capturing.

3.1. The Logical Laws of Attention-Capturing

The logical laws of attention-capturing, as we see it, consist of regularities and patterns established when one content is logically preferred by the attention of the masses over others. They can be categorised into three types.

3.1.1. Logical Law 1 - Context, Contingency and Attractiveness

Logical law 1 can be easily summarised: the invention and recombination of capture content in the digital environment are influenced by the social context, social and community contingencies and the capabilities (lyrical, textual, sound, technical, technological, etc.) lent to the content, and ultimately, shared, recombined and imitated on the various digital platforms.

One such example is the case of YouTube influencers, who tend to combine, in a single content, the general needs of the social context and the contingency of the masses with communicational skills based on persuasive information (Costa, 2020c).

3.1.2. Logical Law 2 - Success Is the Result of Propagation, Adaptation and Compatibility

In logical law 2, the protagonist is the success. The success of content that captures the attention on digital is measured by its ability to spread (shares, comments, reactions, views, etc.) from its place of origin, adapting and making it compatible with various types of imitation possible and provided by the different platforms.

For example, we can cite the case of algorithms that operate based on the numerical success of content: more reactions, expansion, and propagation in feeds. However, this propagation and expansion capability depends on the ability to adapt to the media, that is, the response obtained in the digital media. The discussion on Facebook whether Cristiano Ronaldo touched the ball with his hair or not is great for Facebook and Twitter, but not so much for YouTube because the latter focuses on video moments that browse through personal preferences, nor for Wikipedia, which will always highlight who produced the fact (the goal) validated by the institution International Association Football Federation.

3.1.3. Logical Law 3 - The Content That Captures More Is the Winner of Duels and Accumulator of Strategies

In logical law 3, we assume a historical accumulation of knowledge and techniques in the capture processes. Adopting an attention-capturing strategy is made in a duel with other strategies or in a logic of accumulating other previous strategies (logical combination of capturing strategies). The masses selecting a certain content always means progress regarding attention-capturing. To illustrate this, we can take the case of visual trends that algorithms suggest.

These are at the forefront of attention-capturing at the moment. The fact that Cristiano Ronaldo did not touch the ball generated attention-capturing mainly because he did not accept the decision during the television broadcast. This small controversy generated memes and further developments in the digital networks, where Ronaldo's hair augmentation proposal could be the solution to the "problem". The use of memes or montages is not new, but their continued addition to the events is a way of boosting the topic from the perspective of fun and thus spreading it. In the case of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, it emerged that Ukraine had changed the names of road signs to deceive the advancing troops. That also peculiar issue was the subject of various developments in memes, montages and videos, increasing the capacity to capture attention to the topic. In fact, concerning this conflict, it is possible to see an accumulation of strategies to get messages across: on the Russian side, justifying the invasion; on the Ukrainian side, justifying Russian crime. The memes and variations that add to the subjects express the basic human emotions (fear, anger, disgust, surprise, happiness and sadness) in a game form on digital platforms.

3.2. The Non-Logical Laws of Attention-Capturing

The non-logical laws of attention-capturing are made of regularities and patterns established when one content is illogically more reckoned by the attention of the masses than others.

3.2.1. Non-Logical Law 1 - From the Inner Subjective to the Outer Objective

Non-logical law 1 invades the non-rational side of the individual. For there to be successful attention-capturing through digital content, it has to be able to persuade the individual in their subjectivity. Through active and passive algorithms, platforms discover more personal likings and preferences, increasing the potential for capturing emotional aspects and desires. Here it is not about logic but about intimacy and subjectivity.

For example, we can refer to the pattern of likes and subjectivities when we realise that algorithms fill our feed with (possible) topics and videos on certain subjects. If the user tends to like watching videos of animal life, the suggestions in short videos are full of aspects of animal life. This continuum between likings and subjectivities is streamlined by suggestion algorithms that ultimately capture attention.

3.2.2. Non-Logical Law 2 - From the Social Superior to the Social Inferior, and Vice-Versa

Non-logical law 2 focuses on the relationship between dominant and dominated, between elites and lower castes. The action of the elite is almost always the most suggestive and contagious in attention-capturing. However, some trends start at the base and go viral, often acting on unconscious processes of reception, which eventually reach the elites and thus reinforce or impose themselves. This law is regularly fulfilled in the action of attention-capturing.

A practical example is the case of fashion. The transition of trends from top to bottom is constant. On digital, influencers promote trends at various levels. The biggest Lusophone YouTuber (Luccas Neto) produces fashions and influences among younger people, both in the top-down and bottom-up sense regarding opinions and issues (Costa, 2020c). These influences are not so much at the discursive level but more of the aesthetic type and belonging to a youth group.

3.2.3. Non-Logical Law 3 - The Change and Transition of Fashions, Habits and Customs

Non-logical law 3 is, somehow, related to non-logical laws 1 and 2, where fashions, habits, trends and customs fall into the universe of imitation and repetition. Contingent intellects and aesthetics from particular subjectivities cause changes in fashions, habits and customs in the attention-capturing process.

The TV programme Big Brother has generated specific online programmes with celebrities (the case of the Kardashians). This trend of showing life in real-time is, in a way, similar to what is done on digital networks through the constant sharing of moments and selfies. This form of attention-capturing is quite present in contemporary society. However, its affront and contestation are also a force. Moreover, the forces of contestation tend to provoke ruptures in existing models and traditions. Non-logical law 3 is the law that opposes avant-gardists to conservatives and how new syntheses emerge from it that produce change and transition in practices, habits and customs.

3.3. Laws of Video in Attention-Capturing in Digital Platforms

These laws of attention-capturing are, as we see them, at the origin of the development (and formatting) of contingent intellects - thought structures that, in contingency, grow stronger due to their greater repetition and universal imitation (Costa, 2020a, 2020b, 2021a, 2021b). In that regard, using digital platforms, boosted by algorithms that reinforce our trends, tastes and habits, makes this construction more robust.

Video, in particular, manages to objectify and implement the logical and nonlogical laws of attention-capturing, giving it an imagery sense and concurrently subscribing to the dynamics of capturing at large. It emerges fundamentally on digital platforms as an element that contextualises contingency while seducing with the importance of the moment experienced by the social individual who inhabits digital platforms. Therefore, video as context, contingency and element of seduction is one of the main laws of its strength in capturing attention.

Furthermore, the successful video which propagates itself becomes compatible with the network and lends itself to adaptation to other similar dynamics is also a law of attention-capturing. The most viewed, shared, and permanently updated videos trigger the algorithms and thus strengthen their effectiveness in capturing attention until another takes their place. Paraphrasing Gabriel Tarde (1890/1978), video content emerges and grows through sharing and reaction, then stagnates and finally recedes as new content emerges. This is a simple but very common law on digital platforms.

On the other hand, the video that captures the most views is, obviously, a duel winner. To be so, it needs to accumulate logical strategies: be persuasive, be viral, promote the common (among those who watch it), create tension between opposites and consensus among equals, be capable of replication and parody, and be emotional and creative.

Notwithstanding the logical side of the videos' power of attention-capturing, they also need to attain strong non-logical dimensions to impose themselves: to allow the passage of subjective dimensions of the moment to objective dimensions of exteriority. The eagerness and revolt of Cristiano Ronaldo claiming authorship of the goal against Uruguay at the Qatar 2022 World Cup demonstrates the combative spirit of his ego and how this can be a cause for social discussion as a good or a bad example. Videos with subjective dimensions, amenable to moralising, gain strong success rates.

Also, within the non-logical side of attention-capturing through video, it is important to highlight that the elites and their action give this communication support a superior force. Even if the side of the poor boy who becomes a football player known worldwide constitutes an easy imagination for creating social engagement and adherence, the truth is that it is from arriving at the top that this type of visual content starts to gain dimension and capacity of capture. In other words, arriving or departing from someone of the elite makes a difference in the art of attention-capturing.

Finally, a non-logical law in the video is the rupture with socially established fashions, habits and customs. The challenge to the established and conventionalised clashes with the traditionalist side, imposing a non-logical duel between avant-gardists and traditionalists, which tends to be a success in digital environments. Going back to the example of Cristiano Ronaldo, the videos that started challenging him as an exemplary professional got great reach, especially because they mixed followers and challengers in a non-logical battle between gratitude and ingratitude.

4. Final Considerations

This reflection analyses types and laws of attention-grabbing in digital platforms, focusing on video as a method and technique. Our choice for a benign reflection around an almost glossy subject is aimed at allowing the reader to extend their reflections on the laws of attention-capturing in more complex and profound topics. It is a still recent topic from the perspective we present here, and as such, we have opted for a first approach with a light segmentation, more of a superficial type, so that simple questions about this issue may arise. Later on, this topic will have to be deepened with greater systematisation and analysis points.

The connection of the topic on the economy of attention with methods and techniques of attention-capturing at large and attention in digital platforms with video as support, in particular, suggests the theoretical, methodological and empirical potential of its study within studies on the processes of socialisation in the digital and on the reception studies and studies of usages and gratifications. In As Leis da Imitação, Tarde (1890/1978) argued that imitation and social influence play a key role in forming public opinion and that ideas and opinions spread through networks of individuals the same way diseases spread through populations. This idea of social imitation can be constantly applied to the study of algorithms used by technology companies to capture users' attention and disseminate information, as these algorithms often leverage social networks and behavioural data to direct and shape what people see and pay attention to on digital. By understanding the mechanisms of imitation and social influence, one can tap into lines of research and reflection on how algorithms are used to capture and shape attention and understand how these technologies can contribute to mass opinion formation. This concern of Gabriel Tarde tuned, at once, the concerns of Walter Lippmann (1997), Habermas (1981/1992) and Niklas Luhmann (2009), among others, around the mass phenomenon that is social imitation, and how this is a powerful social tool in societies' development. We believe the current sociotechnical contingency, based on digital networks and image movement, generates a global imitation movement of forms and techniques of attention-capturing. In the light of the Tardean perspective, the examples cited show, on a broader observation, typical profiles of use, consumption and production. The behaviour of suggestion algorithms themselves proves the repetition of formulas that capture attention. That behaviour is based on offering the user video sequences with similar formal structures promoting forms of social imitation in reaction and production.

It would be important, drawing on this, to make a systematic and exhaustive compilation of the methods and techniques for capturing attention overall for video and photography, not only for audiovisual production technicians but also to alert and raise awareness among the general population, who are often unaware of the dangers of the inability to empower themselves before retention and loyalty strategies aimed at big profits. Big profits can have highly damaging and transformative strategies of societies behind apparent capture strategies. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also in the elections Trump won, we realise how the attention-capturing has concrete goals of manipulation, whether institutional or counter-institutional (Sousa & Costa, 2022). The truth, during the pandemic, revolved around what Bruno Latour (2020) warned us about rather than the media or the digital platforms themselves: the issues of interest had more power and more capacity of capture than the issues of fact. That is to say, attention-capturing has a great potential danger in information because we realise, with these reflections on logical and non-logical laws, how emotional and subjective contents, coupled with their algorithmic playfulness, are strong elements in creating moral and group clusters. The creation of groups that antagonise each other over a particular moral issue is partly the result of attention-capturing strategies that, through algorithms, strike at subjective dualities and divergences. Some showmanship and sensationalism are needed to capture the masses, which presupposes a numerical logic of success for attentioncapturing strategies. In this sense, more than typifying attention-capturing strategies and techniques to teach professionals how to do it well, it is urgent to provide citizens with this type of knowledge so that, by becoming aware of these types of strategies, they can be critical and reflective enough to understand in which informational and reticular dynamics they are included. Thus, attentioncapturing laws should be studied as a principle for combating misinformation, sensationalism and innocuous retention loyalty in digital platforms, considering the various implications of their uses and gratifications.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P., under the project UIDB/00736/2020 (base funding) and UIDP/00736/2020 (programme funding)

REFERENCES

ALL GAMES. (2022, 30 de novembro).Fire unreal scenes!! Cristiano Ronaldo trying to claim Bruno goal after game pt smiling face with open mouth and cold sweat |#cr7#cr7header#goal [Vídeo]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oG-OTyt0YRc [ Links ]

Anderson, C. T. (2013). Athazagoraphobia, the fear of forgetting. TheMidwestQuarterly, 54(4), 334-388. [ Links ]

Costa, P. R. (2012). A ecranovisão do terror no século XXI. Comunicando, 1(1), 159-167. https://hdl.handle.net/1822/37441 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R. (2014). Da cultura do ecrã na visão: Alguns resultados de uma abordagem epistémica desobediente. Revista Comunicando, 3, 178-202. https://doi.org/10.58050/comunicando.v3i1.173 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R. (2020a). Uma cartografia do ódio no Facebook: Gatilhos, insultos e imitações. Comunicação Pública, 15(29), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.4000/cp.11367 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R. (2020b). Impactos da captologia. Problemáticas, desafios e algumas consequências do “dar vistas” ao ecrã em rede. Sociologia Online, 23(1), 74-94. https://doi.org/10.30553/sociologiaonline.2020.23.4 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R. (2020c). A presença de arquétipos nos youtubers: Modos e estratégias de influência.Galáxia, 45, 5-19. https://doi.org/10.1590/198225532020347613 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R. (2021a). Da ferramenta ao intelecto algorítmico: Sobreviver entre dilemas digitais. Journal of Digital Media & Interaction, 4(10), 21-37. https://doi.org/10.34624/jdmi.v4i10.24568 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R. (2021b). O ethos wikipedista como modo de combate à desinformação. Liinc Em Revista, 17(1), Artigo e5630. https://doi.org/10.18617/liinc.v17i1.5630 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R. (2021c). A sociedade enquanto duelo de imitações. Uma releitura de Tarde, G. (1978 [1890]). As leis da imitação. Porto: Rés Editora. Revista Ciências Humanas, 14(2), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.32813/21791120.2121.v14.n2.a792 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R., & Capoano, E. (2020). O medo do consumo solitário: Comentários nos canais infanto juvenis de YouTube do Brasil e de Portugal. Journal of Iberian Latin-American Research, 26, 407-426. https://doi.org/10.1080/13260219.2020.1909872 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R., Capoano, E., & Barredo, D. I. (2022). A captura da atenção. De periferia temática à urgência na investigação, no ensino e na legislação. In P. R. Costa, E. Capoano, & D. Barredo (Eds.), Organizações e movimentos periféricos nas redes digitais ibero-americanas (pp. 15-39). CIESPAL. [ Links ]

Costa, P. R., Perneta, P., & Martins, M. L. (2021). Wikipédia em língua portuguesa. Dinâmicas, estruturas e dilemas na colaboração para o conhecimento. Revista Ciências Humanas, 14(2), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.32813/21791120.2121.v14.n2.a747 [ Links ]

Crawford, M. B. (2015). Introduction, attention as a cultural problem. The world beyond your head: On becoming an individual in an age of distraction. Straus and Giroux. [ Links ]

Davenport, T., & Beck, J. (2001). The attention economy: Understanding the new currency of business. Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G. (2000). Diferença e repetição (L. Orlandi & R. Machado, Trads.). Relógio D’Água. (Trabalho original publicado em 1968) [ Links ]

Eisenstein, E., & Estefanon, S. (2011). Geração digital: Riscos das novas tecnologias para crianças e adolescentes. Revista Hospital Universitário Pedro Ernesto, 10(2), 42-53. [ Links ]

Elias, N. (1993). O processo civilizador. Volume 2: Formação do estado e civilização (R. Jungmann, Trad.). Zahar. (Trabalho original publicado em 1939) [ Links ]

GOAL Brasil [@goalbrasil]. (2022, November 29). Gol do Cristiano Ro... não, é do Bruno Fernandes! Astonished face soccer ball Recriamos o gol que colocou Portugal nas oitavas no Qatar pt ballot box check #sportsnews #copadomundo #goalbrasil [Video]. Tiktok. https://www.tiktok.com/@goalbrasil/video/7171400325687987461 [ Links ]

Grados, C., & Gabriela, L. (2020). El uso de TikTok como herramienta para generar content marketing por las marcas dirigidas a jóvenes de 17 a 25 años [Trabalho de investigação, Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas]. Repositório Académico UPC. http://hdl.handle.net/10757/653667 [ Links ]

Habermas, J. (1992). Teoría de la acción comunicativa, Vol. II. crítica de la razón funcionalista (M. J. Redondo, Trad.). Taurus. (Trabalho original publicado em 1981) [ Links ]

Han, B-C. (2018). A expulsão do outro - Sociedade, perceção e comunicação hoje (M. S. Pereira, Trad.). Relógio D’Água. (Trabalho original publicado em 2018) [ Links ]

Higgins, S. S., & Ribeiro, A. C. (2018). Análise de redes em ciências sociais. ENAP. [ Links ]

Jemielniak, D. (2020). Wikipedia as a role-playing game, or why some academics do not like Wikipedia. Wikipedia @ 20. https://wikipedia20.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/wikipedia-as-rpg [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2009). Cultura da convergência (S. Alexandra, Trad.). Aleph. (Trabalho original publicado em 2006) [ Links ]

Jung, C. G. (1969). O eu e o inconsciente (D. F. da Silva, Trad.). Vozes. [ Links ]

Kerckhove, D. (1997). A pele da cultura (L. Soares & C. Carvalho, Trads.). Edições 70. (Trabalho original publicado em 1995) [ Links ]

Lagrange, H. (2020). Les maladies du bonheur. PUF. [ Links ]

Lanier, J. (2010). Gadget: Você não é um aplicativo! (C. Yamagami, Trad.). Saraiva. (Trabalho original publicado em 2010) [ Links ]

Lanier, J. (2018). Dez argumentos para você deletar agora suas redes sociais (B. Casotti, Trad.). Editora Intrínseca. (Trabalho original publicado em 2018) [ Links ]

Latour, B. (2012). Reagregando o social. Uma introdução à teoria do ator-rede. EDUFBA. [ Links ]

Latour, B. (2020). Por que a crítica perdeu a força? De questões de fato a questões de interesse. Cadernos do Departamento de Filosofia da PUC-Rio, 29(46), 173-204. https://doi.org/10.32334/oqnfp.2020n46a748 [ Links ]

Lipovetsky, G., & Serroy, J. (2010). O ecrã global. Cultura mediática e cinema na era hipermoderna (P. Neves, Trad.). Edições 70. (Trabalho original publicado em 2007) [ Links ]

Lippmann, W. (1997). Public opinion. Free Press Paperbacks. [ Links ]

Loureiro, L. M. (2011). O ecrã da identificação [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade do Minho]. RepositóriUM. https://hdl.handle.net/1822/20462 [ Links ]

Luhmann, N. (2009). A opinião pública. In J. P. Esteves (Ed.), Comunicação e sociedade (pp. 163-191). Livros Horizonte. [ Links ]

Martens, B. (2016). An economic policy perspective on online platforms (JRC Technical Report). European Comission. [ Links ]

Martins, M. L. (2011). Crise no castelo da cultura - Das estrelas para os ecrãs. Grácio Editora. [ Links ]

Martins, M. L. (2021). Das palavras e ideias às imagens, sons e emoções. In M. L. Martins (Ed.), Pensar Portugal - A modernidade de um país antigo (pp. 185-192). UMinho Editora. [ Links ]

McLuhan, M. (2007). Os meios de comunicação como extensões do homem (D. Pignatari, Trad.). Cultrix. (Trabalho original publicado em 1964) [ Links ]

Miranda, J. B. A. (2008). Envios. Uma experimentação filosófica na internet. Nova Vega. [ Links ]

Neves, J. P., & Costa, P. R. (2020). Eu sou tu. Uma ecossociologia da individuação. In J. P. Neves, P. R. Costa, P. de V. Mascarenhas, I. T. de Castro, & V. R. Salgado (Eds.), Eu sou tu. Experiências ecocríticas (pp. 25-48). CECS. http://doi.org/10.21814/1822.68550 [ Links ]

Patino, B. (2019). A civilização do peixe-vermelho: Como peixes-vermelhos presos aos ecrãs dos nossos smartphones. Gradiva. [ Links ]

Reagle, J. (2010). “Be Nice”: Wikipedia norms for supportive communication. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia, 16(1-2), 161-180. [ Links ]

Rijshouwer, E. (2019). Organizing democracy: Power concentration and selforganization in the evolution of Wikipedia. Erasmus University Press. [ Links ]

RTP. (2022, 28 de novembro). Bruno Fernandes marca golo frente ao Uruguai [Vídeo]. Facebook. https://fb.watch/hwjfPwgODw/ [ Links ]

Simmel, G. (1950). Quantitative aspects of the group. In K. H. Wolff (Ed.), The sociology of Georg Simmel (pp. 87-180). Free Press. [ Links ]

Sousa, V., & Costa, P. R. (2022). The fitting memory. How the COVID-19 pandemic blended past with present? ODEERE, 7(2), 93-113. https://doi.org/10.22481/odeere.v7i2.10763 [ Links ]

Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform capitalism. Polity Press. [ Links ]

swann ritossa [@swannfreestylee]. (2022, 12 de dezembro). Portugal pt World Cup trophy the end #fastfootcrew #football #portugal #morocco #qatar2022 #worldcup [Vídeo]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/CmFBUh4rmqa/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link [ Links ]

Tarde, G. (1978). As leis da imitação (C. F. Maia & M. M. Maia, Trads.). Rés Editora. (Trabalho original publicado em 1890) [ Links ]

Tarde, G. (1992). A opinião e as massas (E. Brandão, Trad.). Martins Fontes. (Trabalho original publicado em 1901) [ Links ]

Tkacz, N. (2015). Wikipedia and the politics of openness. University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Zagalo, N. (2012, 27 de outubro). Ávidos por padrões. Porque jogamos Tetris. Eurogamer. https://www.eurogamer.pt/avidos-por-padroes [ Links ]

Zuboff, S. (2020). A era do capitalismo da vigilância. A disputa por um futuro humano na nova fronteira do poder (L. F. Silva & M. S. Pereira, Trads.). Relógio D’Água. (Trabalho original publicado em 2019) [ Links ]

Received: December 28, 2022; Revised: January 30, 2023; Accepted: January 31, 2023

text in

text in