Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

On-line version ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.9 Braga June 2022 Epub May 01, 2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.4024

Varia. Articles

From the "Collage Effect" to Strategic Communication in the Context of New Technologies: An Analysis of the Virtual Museum of Lusophony on Instagram

1Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

New communication technologies have brought significant corporate organisation and communication changes. In this study, we present some of these transformations, particularly focusing on: the need for organisations to (re)establish symbolic connections within an environment with no physical presence and a reduced ability to create, exchange and maintain the organisational culture and identity. Thus, companies increasingly invest in new practices in social media to stand out in an environment loaded with images and noise where everything seems ephemeral and disjointed. Against the background of a fragmented society, we draw an analysis of the strategic communication of the Virtual Museum of Lusophony during its launch on Instagram. The research demonstrates the cultural organisation joined the social media essentially because it understood it was essential to achieve its purposes and, for coherence and consistency with the strategic communication, anchored by: (a) actions to create a visual pattern that consolidates the organisational identity; (b) a clear editorial line to publish images adding value to aspects of the organisation; and (c) practices implemented using the platform's interactive resources, towards an immediate increase in the engagement with the museum's audience and potential audience.

Keywords: strategic communication; new communication technologies; social media; Virtual Museum of Lusophony; Instagram

O fenómeno das novas tecnologias da comunicação trouxe mudanças significativas nas formas de organização e comunicação nas empresas. Neste estudo, apresentamos algumas destas transformações, sendo que uma delas nos chama a atenção: as organizações precisam de (re)estabelecer conexões simbólicas dentro de um ambiente em que não há presença física e em que se reduz a capacidade de criação, troca e manutenção da cultura e da identidade organizacionais. Nesse sentido, as empresas investem cada vez mais em novas práticas nos média sociais, para sobressair num ambiente carregado de imagens, barulhento, em que tudo parece efémero, desarticulado. Diante do contexto de uma sociedade fragmentada, trazemos o estudo de caso da comunicação estratégica do Museu Virtual da Lusofonia durante o seu lançamento no Instagram. Na pesquisa, observa-se que a entrada da organização cultural neste medium social foi fundamentado essencialmente pela compreensão da organização e dos seus propósitos e, ao mesmo tempo, pela coerência e consistência da comunicação estratégica, ancorados por: (a) ações de criação de um padrão visual que reforça a identidade organizacional; (b) uma linha editorial clara para publicação de imagens que valoriza aspetos da organização; e (c) práticas realizadas a partir de recursos interativos da plataforma, levando a um incremento inicial imediato do relacionamento com os públicos reais e potenciais do museu.

Palavras-chave: comunicação estratégica; novas tecnologias de comunicação; média sociais; Museu Virtual da Lusofonia; Instagram

Introduction

Communication processes continuously change, create and echo new phenomena and relationships in contemporary society. In organisations, it is no different. As technologies evolve to encompass new networks, thus developing new platforms, corporate strategic communication requires constant reinvention, making the area (re)adapt to new practices.

In the last decades, the list of technology innovations in organisations has been quite diverse: email, voice mail, intranet and internet, mobile phones, videoconferences, data storage, blogs, wikis, podcasts, and so many other platforms. Many innovations have changed the companies' organisational and communication methods. Such context has brought several more dynamic and open opportunities and interaction possibilities amongst organisations and audiences. On the other hand, it also brought challenges that made organisations more vulnerable to their collaborators, clients and suppliers.

In this study, we will focus on one of these challenges: the need for organisations to (re)establish symbolic connections within an environment with no physical presence and a reduced ability to create, exchange and maintain the organisational culture and identity (Ruão et al., 2017). Against this background, companies test several strategies to promote the organisation's engagement and identification with their audiences through different social media platforms. These platforms encourage an environment loaded with content, especially leveraged by images, since they convey greater social presence because they act in the symbolic field (Morin, 2002). According to Martins (2011), technologies have connected individuals, creating in them the brain they need, but, at the same time, disarticulated them as citizens, imposing a fragmentary and chaotic destination. Connecting to networks has meant triggering a virtualisation process, in which distinctions become ephemeral and disarticulated, causing what Giddens (1991/1997, p. 23) calls a "collage effect", typical of an environment where space-time is transformed.

Considering this context, the aim of our work is, therefore, to explore the use of new communication technologies in the organisational field. We seek to understand practices in the area more deeply by answering the following question: how does strategic communication establish communication practices within a society so fragmented by images? Thus, we will conduct a case study of strategic communication implemented on the Instagram profile of the organisation Virtual Museum of Lusophony during its launch phase on this social media. The results of this study can assist companies and communication professionals in working on strategic communication from a deeper understanding of the technological context and visual culture.

Organisational and Communication Transformations in the Technological Context

The studies on strategic communication are an emerging field of communication sciences. As Ruão (2020) suggests, strategic communication can be treated as a sub-area of organisational communication. It is dedicated to the purposeful and instrumental analysis of the communication produced by organisations, including companies, institutions, profit and non-profit entities, as is the case of cultural organisations and all other types of stakeholders of our diverse culture today.

Strategic communication seeks to study how the organisation presents itself through planned communication activities related to its purpose, that is, using the "strategic" dimension. Along these lines, Hallahan et al. (2007) propose the notion that strategic communication is prepared to "purposefully advance its mission" (p. 4). Also, Argenti et al. (2005) state that it is "communication aligned with the company's overall strategy, to enhance its strategic positioning" (p. 61), considering strategic communication inexorably related to corporate strategy. In a more recent study, Zerfass et al. (2018) argue that strategic communication is communication that is substantial for the survival and success of an organisation. Based on these definitions, we could also suggest that strategic communication can be described as the stakeholders' permanent application of a communicative perspective to organisational processes related to the organisation's goal (Falkheimer & Heide, 2018).

All communication actions to achieve the organisational goals or purposes eventually drive the companies to make a common effort to create meaning, based on the analysis of the scenarios, internal and external environments, audiences and other issues and research on the organisation. Each one of these processes can define its own tactics and action plans, which are often called "communication strategies" and are the result of a guiding principle of communication aligned to the corporate strategy and the organisational mission so that there is mutual support for building relationships with the publics (Steyn, 2003).

However, the introduction of new communication technologies has revolutionised the world of communication in companies, and especially with the internet, we have had a major phenomenon. By "communication technologies"1, we mean any technological tool or device that enables information to be shared by all or for one-to-one interaction. As for the internet, there are currently 4.95 billion users worldwide (We Are Social, 2022), representing about 62.5% of the global population, with an estimated 6 hours and 58 minutes of daily use. Manuel Castells (1996/2002) uses the network metaphor and notes that we are beginning to live in a period characterised by the "transformation of our 'material culture' operated by a new paradigm around technologies" (p. 33). Thus, a new economic panorama has emerged within this social phenomenon and its interaction with the corporate world. The key operations of management, financing, innovation, production, distribution, and relations between collaborators and customers took place through/on the internet and other networks, regardless of virtual or physical dimensions.

Using the internet as a fundamental means of communication and processing, organisations have adopted the network as their organisational form, what Castells (2001/2007) calls the "network-enterprise". It is "built around a business project resulting from the cooperation between different components of different firms, networking among themselves for the duration of a given business project, and reconfiguring their networks for each project" (Castells, 2001/2007, pp. 90–91). This reconfiguration arose from combining different strategies, such as the internal decentralization of large corporations, which adopted lean horizontal structures of cooperation coordinated around strategic goals. They teamed up with small and medium-sized businesses to reach a wider market, forming associations with large and their ancillary networks. According to Harris and Nelson (2007, p. 375), in the late 20th century, we could see the "virtual organisation" emerge, which is formed by a collaborative learning network that can almost simultaneously produce and deliver products and services at any time, in any place, and any variety, in order to provide customer satisfaction. That was no different for cultural organisations, such as museums, which also began organising their collections and heritage through networks through cooperation with more horizontal structures.

New communication practices were introduced with technological and organisational changes (Martins, 2018). Strategic communication also had to (re)adapt. New communication technologies such as networks have facilitated immediate access to information, quick message transmissions, and collaboration between geographically dispersed participants. They expanded the number of formal channels and favoured the communication of organisations directly with the audiences (Cheney et al., 2011; Miller, 2015). They facilitated the measurement of communication programs through monitoring and online surveys in their channels (Argenti, 2006). Moreover, they also allowed companies to engage in different new specific techniques, such as crowdsourcing2 (Aten & Thomas, 2016) and gamification, which either generate benefits, points or advantages or use the brands, in the case of Sephora, with the Beauty Insider program, or the Starbucks network, with Starbucks Rewards (Kotler et al., 2016/2017), to expand social capital and build relationships with audiences.

The networks, thus, have significantly transformed communication flows with interactivity. The capacity provided for bidirectionality allowed rapid exchanges, the circulation of large volumes of data and increased user activities, making the interaction of individuals who could not express themselves beyond the mass communication, like television and radio, possible. Currently, in strategic communication, the idea of establishing new interactions and links between companies and their audiences is one of the great expectations related to these technologies' capabilities. Companies can create and manage their communication channels, such as websites, blogs, and pages on social media, to allow organisations and brands to communicate more dynamically with their audiences (Mesquita et al., 2020).

However, this scenario has also brought several challenges for strategic communication, requiring companies to deal with new communication issues. The networks' new communication flows, more interactive and dynamic, have left organisations vulnerable and exposed to internal and external environments. For a long time, organisations had control over the placed advertisements, good public relations managers, the topics on the agenda, the positioning in the media, and the sources to which they directed information. Social interactions were also mediated through traditional communication processes and channels such as memos, forms or phone calls. With the networks, it is almost impossible for organisations to control information about themselves since the communication processes are now taking place in multiple environments, accessible both to organisations and to the public, with high intensity and information propagation speed (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010; Mesquita et al., 2020).

Consumer communities became more powerful and no longer afraid of big brands, so they now share stories about them, good and bad. According to Kotler et al. (2016/2017), power has gotten more dispersed, bringing more horizontal and inclusive social norms over rigid political, economic, socio-cultural and religious norms. Technological communication tool possibilities have provided more access to information and a speak one's mind empowerment (O'Kane et al., 2004). Anyone can then produce, consume and make content available, reflecting a shift in the traditional one-way communication model from "one to many" to "many to many" (Mesquita et al., 2020).

New technologies have also disrupted the traditional flow within organisations, often predominantly top-down (Cheney et al., 2011). According to Ruão et al. (2017), access to information across hierarchical levels has reduced departmental barriers. Employees are now creators of information and organisational meaning, more autonomously and multiplying through emails, blogs, forums and other media. At the same time, they have produced a dilution of organisational boundaries with the exterior, in a process where phenomena described for the internal universe also occur in the relationship with the external publics.

With such a breakdown of boundaries between the internal and external environment, information can reach many people in a short time, which can improve a company's reputation or quickly destroy it. Thus, monitoring the content on the networks is increasingly important, as it is a competitive advantage to avoid crises. This practice makes it possible to increase positive mentions, identify advocates/brand ambassadors, retain, engage, build loyalty among the audiences, generate traffic to the official website, and reinforce brand awareness. It can also be a source of data for studies that aim to develop new strategies (Barichello & Machado, 2015; Mesquita et al., 2020).

The new communication technologies have made organisations evolve a lot in the last decades and have installed an environment of great complexity and sophistication of communication. We have seen in this topic that new forms of organisation are highly dynamic, open, and receptive to innovation. They are decentralized, horizontal, and formed around teams or specific projects. Alongside technological and organisational practices, new strategic communication practices have emerged. These offer multiple possibilities for interaction among organisations and their publics, faster access to information and greater collaboration between people at a distance, expanding the companies' formal channels, measurement programmes and new techniques for engaging their publics. On the other hand, changes also made organisations more vulnerable. They have less control over their employees, customers, and suppliers, for the world's communication environment has become a more turbulent, noisy place, with much information circulating.

Communication Technologies and Organisational and Strategic Communication: A Summary

Communication technologies have the following potential:

more horizontal, decentralised, dynamic cooperation structures, open to innovation;

new work configuration, more individualised, with multiple tasks, conducted in different locations, remotely;

rapid transmission of messages and large volumes of data in different times and spaces;

additional interactivity, expansion of formal channels, new programmes and techniques for public engagement;

a greater possibility of database monitoring and storage.

Moreover, they introduce the following challenges:

the network's horizontality makes communicational power more dispersed. Publics now play an active role;

loss of internal borders and control of information dissemination. Everything can eventually be disclosed. More vulnerable organisations;

communication environment in the world has become a more turbulent, noisy, fragmented place, with a lot of information and content circulating.

The Fragmentation: Compression of Time and Space and the "War" for Content-Based Attention

Besides all the transformations we have seen, the new communication technologies have also compressed time and space, which are crucial elements in all types of human communication. While face-to-face communication, or even phone or video communication, requires the simultaneous participation of the parties, networks have freed communication from this synchrony. That leads to an important discussion between synchronous communication, where participants communicate simultaneously and provide immediate feedback, and asynchronous communication, which does not require the simultaneous participation of the parties. A message can be sent anytime, anywhere, and the receiver will respond within their time and space.

In this respect, Giddens (1991/1997) states that this separation of time and space in modern societies ended up providing the basis for recombining into modes of activities' coordination without the necessary reference to the particularities of place. According to the author, organisations are inconceivable without integrating time and space since they presuppose strict coordination of the actions of physically absent individuals. The "when" of these actions is directly linked to the "where", but now no longer through the place. There has been what Giddens (1991/1997) called the "removal of relationships from their local contexts" and, therefore, "de-contextualization" of organisations (p. 16).

So, organisations face the challenge of establishing symbolic connections within an environment without physical experience. Moreover, such an absence increases the difficulty of sharing important strategies, missions, vision and organisational values, reducing the ability to create, exchange and maintain organisational culture and identity (Ruão et al., 2017). The construction of meaning by these online media is weaker and more volatile. Society intensely perceived this when we followed the worldwide pandemic caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19)3. The situation brought demand for more adaptability and intensified communication through technologies and multiple digital platforms requiring no physical presence, such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, Jitsi Meet, Team Link, etc.

In response to these challenges in sharing organisational culture and identity, organisations began testing new practices to promote communication that would bring identification and proximity with their audiences. As there was a massive adhesion of internet users to social platforms, companies intensified interactive channels, which are more dialogic formats and usually built based on the social network model and the ability to make connections throughout the organisation and beyond.

Several concepts describe this platform that currently integrates our daily practice, such as web 2.0, new media or social media. Each enhances different characteristics and is associated with a specific temporal, geographical and cultural context. The common elements among all concepts are the transition from analogue to digital and the change from a logic of mass broadcasting to a more interactive logic. The term "social media" highlights the promotion of sociability as its primary attribute (Andrade, 2016). A platform like Facebook, also frequently termed a "social network sites" (with the acronym SNS), is an internet service where users can create profiles and build a list of connections with other networked users (Boyd & Ellison, 2007).

Appel et al. (2020) stated that social media is a "technology-centric, but not entirely technological, ecosystem in which a diverse and complex set of behaviours, interactions, and exchanges involving various kinds of interconnected actors (individuals and firms, organisations, and institutions) can occur" (p. 80). Social media has become almost anything, content, information, behaviours, people, organisations, and institutions, that can exist in an interconnected, networked digital environment. They have facilitated the creation, maintenance and possible intensification of everyday interpersonal and social relationships virtually through profiles that can include any information format such as photo, video, audio, and blog (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010). These platforms entail openness, participation, conversation, connectivity and community (Davids & Brown, 2021).

On the other hand, these platforms were severely criticised for the power of using users' information and data (van Dijck et al., 2018), encouraging a content-laden environment. That space is especially leveraged by images, as they convey greater social visibility than text alone and a sense of "idolatry" (Martins, 2011, p. 77), of magic, as a process of virtualization of life. The images foster the aesthetic state (Morin, 2002), consisting of a trance of happiness, grace, emotion, enjoyment, and reproduction and accompanying all life activities, exalt moments, and settings. "Everything that is represented, in the form of a mental image, painted, filmed, holds the 'charm of the image' and everything that refers to aesthetics penetrates our souls, minds, our lives" (Morin, 2002, pp. 134–135).

Therefore, social media platforms like Instagram encourage such sharing of original content by images. They allow posting whatever is possible, all the time, providing technologies through a business model that involves monetising users in this ecosystem (Appel et al., 2020). Furthermore, there is the adherence of several types of people and organisations using these technologies. The first digital natives, generation Z, born between 1996 and 2010, consume information differently than previous generations. They use smartphones, prefer visual content such as videos, photos, and games, have non-linear thinking and converge on different platforms. As they were born digital, they cannot imagine a world where they do not share information, thus contributing to content sharing and this increasingly noisy environment (Apocalypse, 2021).

Launched in 2010, Instagram tallies 1 billion monthly active users and 1 million monthly advertisers (OmnicoreAgency, 2022). It ranked as the second most important social media platform for marketing and strategic communication: 73% of marketers currently use it (Kim et al., 2021). Companies are increasingly creating and managing their official Instagram accounts to build and nurture online communities with consumers due to its ability to increase brand exposure, attract website traffic, and develop loyal fans. Instagram offers users (including businesses) a plethora of features that are easy to use, such as following, following photo or video posts, posting comments on all shared images, and the ability to "like", which, from a strategic communication perspective, indicates the behavioural engagement of audiences (Kim et al., 2021).

Instagram allows users to take pictures and videos with filters like brightness, contrast, saturation, and colour manipulation. One can add a caption to each picture or video, add descriptive hashtags, add links, tag other users in the picture, geotag picture locations and connect to other social media sites (Musonera, 2018). Users can also post stories with pictures or videos for 24 hours so that users can share images in a short period. The stories feature allows more engagement with polls, questions, tests, and the option to keep them highlighted. The app also provides a digital television, IGTV, to play recorded instants anywhere in the world and lives, allowing live interaction. In 2020, the app also announced Reels, a proposal to create short videos with greater reach, similar to the social media Tik Tok (Dinamize, 2022). In other words, Instagram provides the ability to elicit emotional responses from users due to its visual focus (Kim et al., 2021).

In the middle of a "war" for attention, companies have been using several strategies to increase their organisations' visibility and positive brand awareness, reinforced by visual elements to get closer to their audiences. For example, influencer relationships — attribution organisations give some social media users ("Instagrammers") to influence their audiences (Enke & Borchers, 2019). Also, storytelling is stories related to the brand in a narrative to demonstrate and perpetuate the organisation's culture by reinforcing rituals and traditions, establishing more effective links, and attracting more attention (Kim et al., 2021; Weber & Grauer, 2019). Among other practices that seek to integrate online and offline promotions, such as hashtags to open online conversations and calls to action, prompt the audience to take action in a communication situation (Appel et al., 2020). Appel et al. (2020) point out the trends that will continue to shape the social media landscape for organisations in the immediate future: on the one hand, the omni-social presence (which combines online and offline presence), as is the case of the Museum of Ice Cream in New York that has graduated to cult status on Instagram for encouraging artistic content and optimised experiences to post selfies (Pardes, 2017); on the other hand, the rise of influencers and also trust and privacy concerns with brands.

Thus, in an environment with no physical participation and a "war" for content-based attention to promote online visibility, new practices in strategic communication seem to have been established, driving organisations to invest heavily in image-based content. With these new sharing tools, and in a whirlwind of information, audiences develop mental representations, more or less reflected, directly through their own stories, which they also share about brands, products, or the behaviour of companies, in record time (Ruão et al., 2017). This visually stimulated society prompts a further increase in the reproduction of images, making us feel that everything is transitory, ephemeral, and fleeting. It causes what Giddens (1991/1997, p. 23) calls a "collage effect", typical of an environment where space-time is transformed, merging stories and objects, an amalgam of signs which have nothing in common, apart from being " timely" and consequential.

In this society where we are too often led to surrender to the "charm of images" (Morin, 2002), we embark on an unbridled projection, feeding back into a mythological, hyper-real and fragmented culture. It deprives us of the ability to look at ourselves and our otherness or the organisations and their otherness.

Analysis: The Strategic Communication on the Virtual Museum of Lusophony's Instagram

Following this contextualization of the technological environment and contemporary society, in this section, we will analyse the strategic communication of the Virtual Museum of Lusophony for its launch on Instagram. We aim to answer the question of the study: how does strategic communication establish communication practices within a society so fragmented by images? As a methodology, we used the technique of direct observation in the context of the study (Coutinho, 2011), during the period of the museum's launch on Instagram, for 2 months, from December 2021 to January 2022. We also used the technique of the organisation's documentary research by investigating internal regulations and the organisation's channel, Instagram, during the same period. Moreover, we conducted semi-directed interviews4 with the responsible coordinator of the agency that designed the visual pattern of the museum's profile on Instagram and the project designer to understand the formulation, the values and attributes considered for the choice of formats for communication.

The Virtual Museum of Lusophony was created in 2017 as a virtual organisation. It is a platform for academic cooperation in science, teaching and arts among the Portuguese-speaking countries and their diaspora, extending to Galicia and Macau. It congregates, in a common effort, universities, with research and postgraduate teaching projects in communication sciences and cultural studies, and also cultural and artistic associations and all who are interested in the construction of this Lusophone community (Martins, 2017, pp. 46–47; Museu Virtual da Lusofonia, n.d.).

According to its regulations, its fundamental purpose is to

articulate the possibilities of digital technology with the preservation, research and dissemination of the historical and cultural heritage of the Portuguese-speaking countries. On the other hand, it also aims to contribute to the expansion of common knowledge between the Portuguese-speaking countries, drawing their peoples closer and allowing the construction of a more informed future, where intercultural dialogue and respect for the cultural heritage and uniqueness of the other prevails.

Under the post-colonial perspective (Sousa et al., 2022), it is intended to summon the importance of memory in the experiences and relations between Lusophone countries and their diaspora. According to Martins (2018), founder and director of the Virtual Museum of Lusophony,

the purpose is to build knowledge bases at a Lusophone scale, which may represent an important scientific statement in the Portuguese language. Moreover, assembling an important cultural and artistic collection promotes understanding the interdependence from the intercultural communication perspective. (p. 92)

Being in an exclusively virtual environment, the Virtual Museum of Lusophony also aims to promote the active participation of citizens. It makes records available and promotes the (re)construction of the collective memory through a set of activities such as exhibitions, collections, debates, seminars, conferences, studies, and projects, based on the dissemination of knowledge and cultural and artistic heritage (Museu Virtual da Lusofonia, n.d.). The Virtual Museum of Lusophony was launched, in 2020, on the digital platform Google Arts & Culture to leverage these purposes and aspirations. It gained international visibility and provided multiple collections with resources and immersive experiences for visitors. A year later, in 2021, the Virtual Museum of Lusophony became a cultural unit of the University of Minho in Braga, Portugal.

The museum's international launch and its expansion as a cultural unit of a university, and its purpose related to constructing a cultural and artistic heritage involving the active participation of citizens, required communication that would further extend its visibility. That would provide the opportunity to build and expand the knowledge bases to the largest number of people. On the other hand, the museum's new communication policy is expected to increase the dissemination of its collection and set of activities and bring it closer to its internal and external public, promoting the desired active participation.

In line with these objectives, the Virtual Museum of Lusophony launched its communication proposal on social media and intensified it after December 2021. The museum had already a presence on social media, namely on the Facebook and Instagram platforms. However, despite an active account on Instagram and about 100 followers, it had not posted any content on this social media platform until this period.

To promote strategic communication, according to the guidelines of relevant authors in the field (Falkheimer & Heide, 2018; Hallahan et al., 2007; Zerfass et al., 2018), the first step was to research and learn about the internal environment of the museum. Through its culture, identity, mission and objectives, and understanding of the relationships established with the collaborators and their interaction with communication technologies. Furthermore, analyse the external environment, the partners and other museums with online activity on social media and, more specifically, on Instagram to identify the online presence, the main practices, opportunities and challenges of strategic communication for cultural organisations. Lastly, understand the museum's internal and external audiences to establish a closer and more interactive communication.

After this exploratory and research process, it became necessary to consolidate communication in strategic actions aimed at social media. The challenge was building awareness and increasing dissemination and public participation in an environment overloaded with information and inputs. Moreover, the fact that it is a virtual organisation was taken into account; it has more horizontal characteristics but no physical space for interaction and contact with the audiences. Thus, creating a visual pattern for the images posted on the profile was paramount to bring them closer to the Virtual Museum of Lusophony's identity and reinforce it among the audiences. The CreateLab agency, a project affiliated with the Communication and Society Research Centre of the University of Minho, created the design. It was based on the museum's logo. Its geometry of several interconnected ellipses represents the Lusophone world's diversity and the network of its multiple countries and cultures (Figure 1).

A briefing interview with the executive coordinator of the CreateLab agency (M. Alves, March 22, 2022) was conducted to decide on the design of the visual pattern for Instagram, where the purposes and objectives of the organisation and the objectives of strategic communication were explained. Two fundamental axes were evident: one related to the dissemination of cultural heritage, the collection, exhibitions and activities, and the other related to the public's participation in the posts. These axes required a clear visual pattern, appealing to stand out among many other Instagram images. Moreover, it should reproduce the dynamics that would lead to the participation of the museum's public.

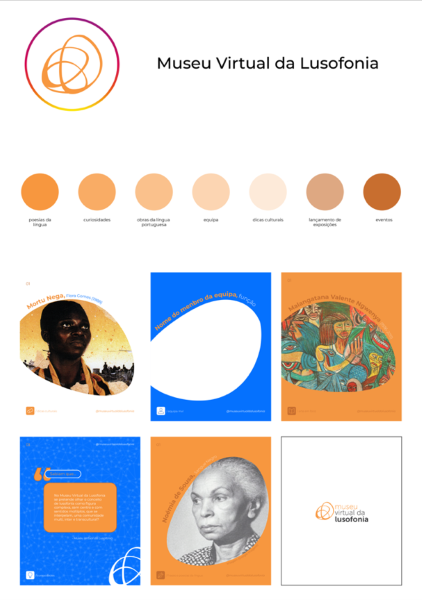

From these strategic guidelines, one of the CreateLab designers who worked on the project (R. Cardoso, interview, March 22, 2022) mentioned the agency would make a complete diagnosis of the museum's other communication channels layout, such as the website and the Google Arts & Culture platform. Its purpose was to adapt and harmonise the pieces that would be developed with the organisation's identity, such as the logo, the colours, and the colour palette (a set of colours that match and complement the colours of the visual pattern). After this analysis, they decided to create something simple, easy to replicate, and simultaneously dynamic so that the public would immediately identify it.

The agency deconstructed the logo based on these insights (Figure 2), producing different graphic elements from the ellipses. These elements are presented individually and simultaneously complement each other in the posts to create a sense of movement and dynamism and refer the public to the museum's logo. Besides the elements of ellipses, a complementary visual pattern was created, a background with connected dots, representing the existing connections between the community of Portuguese-speaking countries to reinforce the museum's identity elements. The colours are based on the gradation of the logo, with the colours orange and white. Another colour palette was adopted to generate more liveliness and differentiation in the posts. According to the agency's research, it includes the blue colour for it complements orange. The proposal was to use three colours, orange, white and blue, and some variations of the palette that alternate in the daily posts on the museum's feed, using the graphic elements of the logo's ellipses and the background represents the connection between the Portuguese language countries.

Figure 2 Deconstruction of the logo of the Virtual Museum of Lusophony. Project for creating the visual pattern of the Instagram feed by the CreateLab agency

According to the interviews with the CreateLab agency, the final proposal was the result of a "strategic process grounded in clear guidelines for the creation of a visual pattern for the feed, and underpinned by the consolidation of the museum's identity" (M. Alves and R. Cardoso, interview, March 22 2022), for the dissemination of its heritage, collections, activities and public participation.

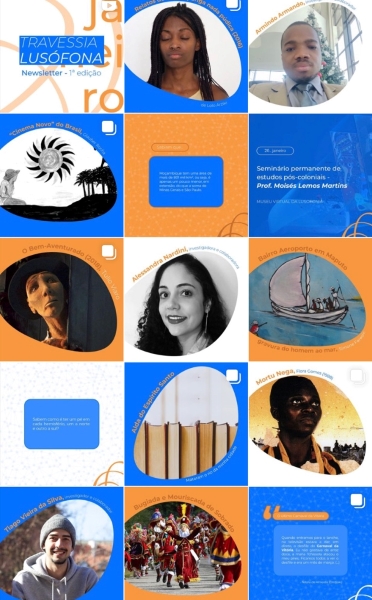

Considering the complex and dynamic environment of Instagram, other communicative actions were studied to ensure the audiences' identification with the museum. From direct observation, between December 2021 and January 2022, it was possible to see that the in-house team was focused on the quality of the content published in images, which reinforced the objectives and purposes of the institution immediately. Therefore, the team developed an editorial line of communication that valued the culture and the organisational identity by producing a social media publishing guide. The public identification was essential to create these communication actions, with an editorial line consistent with the audience and creating a daily content schedule based on the museum's purposes of informing and promoting the dissemination of cultural and scientific knowledge and active participation. The editorial line developed aimed to create a feed that would reproduce in images the plurality of the Portuguese-speaking countries, of the scientific and artistic productions, in a humanised manner, with respect for multiple cultures, through the sense of clarity and dynamism emphasised by the agency (Figure 3). The document was distributed internally to all the museum's cooperation networks to encourage the participation of the team of collaborators and internal researchers and to foster the dissemination of relevant historical and cultural heritage contents, the exchange of knowledge, the collection, the scientific and cultural activities and the promotion of intercultural dialogue.

Figure 3 Image of the feed from January 2022 reflecting the editorial line developed based on the dissemination of the cultural activities of the museum, appreciation of the collaborators and intercultural dialogue of the Portuguese-speaking countries

In order to amplify the participation also of external audiences, there was also a concern with the approach and relationship, from the use of various interactive features present in the Instagram tool: personalized responses to comments from followers direct; use of stories to generate polls, questions, highlights; features of publications of images in the feed-in carousel format, and with the use of videos and Reels to expand the scope of posts; use of hashtags to bring online conversations; and the call to action (Appel et al., 2020). Regarding the numbers, the most tangible result on Instagram is the increase in the number of followers, which leapt from 100 to 495 followers in just 1 month (232% growth compared to December 2021, when the account was launched). The average engagement per post (considering the number of likes, shares and comments) was 19.65 interactions per post in the feed in the first month of content posting. The data cited can be found in Oliveira and Ruão (2022), where they will be updated.

In summary, we could identify that the Virtual Museum of Lusophony joining the social media platform Instagram, and establishing its online presence through its contents and interactions, was based on understanding the organization and its purposes, the internal and external environments, and identifying their publics. After this analysis, communicative actions were proposed that were based essentially on:

the creation of a visual pattern reinforcing the organisation's identity;

the development of a clear editorial line for posting images which valued the culture and the organisational identity through the production of a social media publishing guide;

moreover, using the platform's interactive resources for relationships and closeness with the public.

These actions allowed for an initial increase in the relationship with the museum's current and potential public through the increase of the community (followers) and participation and engagement (interaction of the followers with the museum). They also reinforced elements of culture and identity for the collaborators and the museum's cooperation network to feedback the external communication on Instagram.

In the case presented on the strategic communication for launching the Virtual Museum of Lusophony on the Instagram platform, the communication was grounded in its objectives and purposes. It sought to escape the ephemerality of images published on Instagram social media, which was highly sustained by the culture and identity, and the museum's organisational objectives, through an environment stimulating the followers' participation through the interactivity features of the social media platform.

Final Considerations

We began the study by showing the organisations' major transformations with technological advances. Consequently, new communication practices have been introduced. That was no different from strategic communication, which made possible the interaction between organisations and their publics, faster access to information, greater collaboration between people at a distance and the expansion of formal corporate channels. However, these changes have also left the organisations more vulnerable and less control over their collaborators, clients and suppliers since time and space have been compressed. The communication environment in the world has become a more turbulent, noisy place with a kind of "war" for contents and images circulating. It has made us feel that everything is transitory, ephemeral, and fleeting. In this work, we observe that organisations began testing new practices to promote communication that would bring identification and proximity with their audiences from the challenges of sharing the important organisational culture and identity.

As we have seen throughout this article and the analysis of the Virtual Museum of Lusophony, it seems that the challenge to stand out in a fragmented and transient environment of physical absence is not to establish a "collage effect" (Giddens, 1991/1997) through communication. A collage of the pieces fragmented by social media in contemporary society, providing publications that do not connect, mix signs and do not convey meaning to the audiences. It is essentially about understanding the organisations and their purposes (including the new forms of organisation, such as the virtual ones). It is about the coherence and consistency of the strategic communication with its internal and external publics, to resume the look on the organisations themselves, (re)establish the look on the other, and the otherness, through communication.

This insight about the organisations involves understanding the changing landscape, causing companies to strengthen symbolic connections through culture and identity and promote interactivity in its various forms of human communication, either by interpersonal (offline), but also through technological resources (online), through questions, polls, comments, dialogue. Thus, organisations can promote new ideas, productions, and proposals and constantly (re)formulate practices and strategies in social media, making them even more dynamic and flexible from the consistent, coherent and connected public participation.

It is also noteworthy that new researches with the Virtual Museum of Lusophony are currently underway to further investigate the strategic communication with the public within the environment of new technologies and social media.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under project UIDB/00736/2020 (base funding) and UIDP/00736/2020 (programmatic funding).

REFERENCES

Andrade, J. G. (2016). Relações públicas e mídia sociais: Os desafios da gestão com os públicos. In M. Túñez López & C. Costa-Sánchez (Eds.), Interação organizacional na sociedade em rede: Os novos caminhos da comunicação na gestão das relações com os públicos (pp. 121-136). Sociedad Latina de Comunicación Social. https://doi.org/10.4185/cac102 [ Links ]

Argenti, P. A. (2006). How technology has influenced the field of corporate communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 20(3), 357-370. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1050651906287260 [ Links ]

Argenti, P. A., & Barnes, C. M. (2009). Digital strategies for powerful corporate communications. The McGraw-Hill Companies. [ Links ]

Argenti, P. A., Howell, R. A., & Beck, K. A. (2005). The strategic communication imperative. MIT Sloan Management Review, 46(3), 61-67. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/...ication-imperative/ [ Links ]

Apocalypse, F. (2021). Por uma nova comunicação interna: Impactos tecnológicos e novas funções. In C. Terra, B. Dreyer & J. Raposo, J. (Eds.), Comunicação organizacional: Práticas, desafios e perspectivas digitais. Editora Summus. [ Links ]

Appel, G., Grewal, L., Hadi, R., & Stephen, A. T. (2020). The future of social media in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(1), 79-95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00695-1 [ Links ]

Aten, K., & Thomas, G. F. (2016). Crowdsourcing strategizing: Communication technology affordances and the communicative constitution of organizational strategy. International Journal of Business Communication, 53(2), 148-180. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2329488415627269 [ Links ]

Barichello, E., & Machado, J. (2015). Relações públicas em novas mídias: O papel do monitoramento digital na comunicação das organizações. In G. Gonçalves & F. L. Filho (Eds.), Novos media e novos públicos (pp. 66-82). Livros LabCom. [ Links ]

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210-230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2002). A era da informação: Economia, sociedade e cultura I. A sociedade em rede (A. Lemos, Trad.). Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. (Trabalho original publicado em 1996) [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2007). A galáxia da internet: Reflexões sobre internet, negócios e sociedade (R. Espanha, Trad.). Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. (Trabalho original publicado em 2001) [ Links ]

Cheney, G., Christensen, L. T., Zorn, T., Jr., & Ganesh, S. (2011). Organizational communication in an age of globalization: Issues, reflections, practices. Waveland Press. [ Links ]

Coutinho, C. (2011). Metodologia de investigação em ciências sociais e humanas: Teoria e prática. Edições Almedina. [ Links ]

Davids, Z., & Brown, I. (2021). The collective storytelling organisational framework for social media use. Telematics and Informatics, 62, Artigo 101636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101636 [ Links ]

Dinamize. (2020, 27 de novembro). 9 recursos do Instagram que podem melhorar a experiência do cliente. Blog Dinamize. https://www.dinamize.com.br/...ursos-do-instagram/ [ Links ]

Eisenberg, E., Goodall, H. L., Jr., Trethwey, A. (2010). Organizational communication: Balancing creativity and constraint. Bedford/St. Martins. [ Links ]

Enke, N., & Borchers, N. S. (2019). Social media influencers in strategic communication: A conceptual framework for strategic social media influencer communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(4), 261-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1620234 [ Links ]

Falkheimer, J., & Heide, M. (2018). Strategic communication: An introduction. Routledge. [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (1997). Modernidade e identidade pessoal (3.ª ed.; M. V. de Almeida, Trad.). Celta Editora. (Trabalho original publicado em 1991) [ Links ]

Hallahan, K., Holtzhausen, D., van Ruler, B., Verčič, D., & Sriramesh, K. (2007). Defining strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 1(1), 3-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15531180701285244 [ Links ]

Harris, T., & Nelson, M. (2007). Applied organizational communication: Theory and practice in a global environment (3.ª ed.). Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003 [ Links ]

Kim, B., Hong, S., & Lee, H. (2021). Brand communities on Instagram: Exploring fortune 500 companies’ Instagram communication practices. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 15(3), 177-192. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2020.1867556 [ Links ]

Kotler, P., Hermawan, K., & Setiawan, I. (2017). Marketing 4.0: Mudança do tradicional para o digital (P. E. Duarte, Trad.) . Conjuntura Actual Editora; Edições Almedina. (Trabalho original publicado em 2016) [ Links ]

Martins, M. (2011). Crise no castelo da cultura: Das estrelas para os ecrãs (1.ª ed.). Grácio Editor. [ Links ]

Martins, M. L. (2017). Comunicação da ciência, acesso aberto do conhecimento e repositórios digitais. O futuro das comunidades lusófonas e ibero-americanas de ciências sociais e humanas. In M. L. Martins (Ed.), A internacionalização das comunidades lusófonas e ibero-americanas de ciências sociais e humanas - O caso das ciências da comunicação (pp. 19-59). Húmus https://hdl.handle.net/1822/51039 [ Links ]

Martins, M. L. (2018). Portuguese-speaking countries and the challenge of a technological circumnavigation. Comunicação e Sociedade, 34, 87-101. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.34(2018).2937 [ Links ]

Mesquita, K., Ruão, T., & Andrade, J. G. (2020). Transformações da comunicação organizacional: Novas práticas e desafios nas mídias sociais. In Z. Pinto-Coelho, T. Ruão, & S. Marinho (Eds.), Dinâmicas comunicativas e transformações sociais. Atas das VII Jornadas Doutorais em Comunicação & Estudos Culturais (pp. 281-303). CECS. https://hdl.handle.net/1822/68404 [ Links ]

Miller, K. (2015). Organizational communication: Approaches and process. Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Morin, E. (2002). O método 5: A humanidade da humanidade. Sulina. [ Links ]

Musonera, E. (2018). Instagram: A photo sharing application. Journal of the International Academy for Case Studies, 24(4), 1-9. https://www.abacademies.org/...plication-7773.html [ Links ]

Museu Virtual da Lusofonia. (s.d.). Apresentação. https://www.museuvirtualdalusofonia.com/...ntacao/ [ Links ]

O’Kane, P., Hargie, O., & Tourish, D. (2004). Communication without frontiers: The impact of technology upon organizations. In O. Hargie & D. Tourish (Eds.), Key issues in organizational communication (pp. 172-187). Routledge. [ Links ]

Oliveira, T., & Ruão, T. (2022). Média sociais do Museu Virtual da Lusofonia (Versão V2) (Data Set). Repositório de Dados da Universidade do Minho. https://doi.org/10.34622/datarepositorium/H0RCIC [ Links ]

OmnicoreAgency. (2022, 22 de fevereiro). Instagram by the numbers: Stats, demographics & fun facts. https://www.omnicoreagency.com/...gram-statistics/ [ Links ]

Pardes, A. (2017, 27 de setembro). Selfie factories: The rise of the made-for-Instagram museum. Wired. https://www.wired.com/...ctories-instagram-museum/ [ Links ]

Rice, R. E., & Leonardi, P. M. (2014). Information and communication technologies in organizations. In L. Putnam & D. K. Mumby (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research and methods (pp. 425-448). Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Ruão, T. (2020). A comunicação enquanto estratégica. In J. Félix (Ed.), Comunicação estratégica e integrada (pp. 27-39). Rede Integrada Editora. [ Links ]

Ruão, T., Neves, R., & Zilmar, J. (2017). A comunicação organizacional sob a influência tecnológica: Um paradigma que veio para ficar. In T. Ruão, R. Neves, & J. Zilmar (Eds.), A comunicação organizacional e os desafios tecnológicos: Estudos sobre a influência tecnológica nos processos de comunicação nas organizações (pp. 5-12). CECS. https://hdl.handle.net/1822/54053 [ Links ]

Sousa, V., Capoano, E., Costa, P. R., & Pimenta, C. (2022). Uma reflexão sobre pós-colonialidade, decolonização e museus virtuais. O caso do Museu Virtual da Lusofonia. Comunicação, Mídia e Consumo, 19(54), 80-105. https://doi.org/10.18568/cmc.v18i54.2528 [ Links ]

Steyn, B. (2003). From strategy to corporate communication strategy: A conceptualisation. Journal of Communication Management, 8(2), 168-183. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632540410807637 [ Links ]

van Dijck, J. Poell, T., & De Wall, M. (2018). The platform society: Public values in a connective world. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

We Are Social. (2022, 26 de janeiro). Digital 2022: Another year of bumper growth. Our Insights. https://wearesocial.com/...ear-of-bumper-growth-2/ [ Links ]

Weber, P., & Grauer, Y. (2019). The effectiveness of social media storytelling in strategic innovation communication: Narrative form matters. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(2), 152-166. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1589475 [ Links ]

Zerfass, A., Verčič, D., Nothhaft, H., & Werder, K. P. (2018). Strategic communication: Defining the field and its contribution to research and practice. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 487-505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1493485 [ Links ]

Notes

1We use the concept of communication technologies because we understand the importance of the imbrication of the relationships between organisations and technology. The term is cited by Eisenberg et al. (2010), Cheney et al. (2011), and other theorists of organisational communication. There are also the terms electronic communication or e-communication in O'Kane et al. (2004) and information and communication technology, which also emphasises information (Rice & Leonardi, 2014).

2Crowdsourcing is the practice of outsourcing tasks that company employees would traditionally perform to the members of the public through tools such as community forums that allow customers and stakeholders to give suggestions and ideas about a product, business or service. It is a way of engaging consumers and creating new ways of doing business (Argenti & Barnes, 2009).

3 In late January 2020, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 as an international public health emergency, provoking measures of physical distancing such as lockdown and remote work.

4The interviews' purpose is to understand the participants' viewpoint and how they think, interpret or explain the behaviour in the natural context under study, in this case, the organisation (Coutinho, 2011). They are semi-directed as they are not entirely open-ended, nor do they have many objective questions. The researcher has somewhat open-ended guiding questions but will not necessarily ask all the questions in the planned sequence. The researcher will let the interviewee speak openly, with the words they wish and in the order that suits them.

Received: April 07, 2022; Revised: June 02, 2022; Accepted: June 02, 2022

text in

text in