Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Lusófona de Estudos Culturais (RLEC)/Lusophone Journal of Cultural Studies (LJCS)

versão impressa ISSN 2184-0458versão On-line ISSN 2183-0886

RLEC/LJCS vol.10 no.2 Braga dez. 2023 Epub 28-Fev-2024

https://doi.org/10.21814/rlec.4696

Thematic Articles

There's a Monster in My Mirror: An Analysis of the Autobiographical Graphic Novel Monstrans: Experimenting with Horrormones, by Lino Arruda

iPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Letras: Linguagens e Representações, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Bahia, Brazil

iiDepartamento de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras: Cultura, Educação e Linguagem, Universidade Estadual do Sudoeste da Bahia, Bahia, Brazil

This article seeks to debate the construction of queer narratives in alternative forms of language, such as comics, by compiling relevant literature within the theoretical scopes of gender studies, art history and comics. Autobiographical comics offer countless possibilities for reflection because they incorporate visual elements into the narrative construction. When it comes to an autobiographical illustration, readers have a glimpse of how the artist views themselves in their memories and what they propose to expose. To explore the potential for interpreting and analysing queer autobiographical comics, this discussion centres on the graphic novel Monstrans: Experimentando Horrormônios (Monstrans: Experimenting with Horrormones) by Lino Arruda (2021). This work features deformed watercolour lines that construct the narrative of the author's memories in his journey to understanding his gender identity. The intention is to reflect on the theme of monstrosity present in this work and how it can be a stylistic resource and a means of critiquing the self-representation of dissident bodies, focussing specifically on the artist's relationship with the mirror, a recurring element in other transvestite/trans comics also mentioned in this article.

Keywords: monstrosity; self-representation; transsexuality; comics

O presente artigo busca debater a construção de narrativas queer em outras formas de linguagem, como os quadrinhos, através do levantamento de bibliografias dentro dos escopos teóricos dos Estudos de Gênero, História da Arte e Quadrinhos. Uma autobiografia em quadrinhos pode apresentar inúmeras possibilidades de reflexão por se tratar de uma obra que permite que a imagem também seja parte da construção narrativa, pois, quando se trata de uma ilustração autobiográfica, temos a oportunidade de vislumbrar a imagem que o artista tem de si e se propõe a expor. Com o intuito de investigar as possibilidades de interpretação e análise de uma obra autobiográfica queer em quadrinhos, tal debate será construído por meio da análise do romance gráfico Monstrans: Experimentando Horrormônios, de Lino Arruda (2021), que traz, em sua publicação, traços disformes e aquarelados que constroem a narrativa das memórias do autor em seu processo de compreensão de sua identidade de gênero. Propõe-se refletir sobre a temática da monstruosidade presente nesta obra e como ela pode funcionar como recurso estilístico e crítica da autorrepresentação de corpos dissidentes, focando, especificamente, na relação do artista com o espelho, instrumento frequentemente visto em outras obras em quadrinhos de autoria travesti/trans também aqui mencionadas.

Palavras-chave: monstruosidade; autorrepresentação; transexualidade; quadrinhos

1. Introduction

Comics can be regarded as a unique form of language that combines words and images to convey content. Through a story constructed by sequential arrangement of drawings and texts, it is possible to engage in discussions through narrative resources such as humour, suspense, drama and even from a perspective of social criticism. What makes comics particularly fascinating is their plurality. From the iconic superheroes created by major foreign publishers such as Marvel Comics or DC Comics to independently published productions that explore creative freedom, as well as journalistic graphic art and children’s niche, as seen in the works of Brazilian producer Maurício de Sousa Produções, comics demonstrate that there is room for everyone within this artistic category, for both creators and consumers. Narrowing down the discussion, we can consider, for example, comics’ receptiveness to diversity through art that manifests both in writing and illustrations. They can provide a platform for exploring themes related to sexuality and gender identities. By analysing independent and/or autobiographical publications, it is possible to gain insights into how these themes can circulate in comics and the extent of their impact, examining how they are explored.

Comics are present in diverse cultures worldwide, and their productions, while often distinct and unique, have the power to communicate with the reader in multiple ways, as it is a field with a myriad of themes. Definitions of comics and how they are constructed and classified can vary according to the time or place in which theoretical studies on the subject emerge. This variability in meaning is influenced by language, perspectives, and even political contexts. In his thesis, Alexandre Linck Vargas (2015) explores the multitude of approaches to comics around the world, highlighting how the terminology used often shapes the way a particular social niche perceives this medium:

part of the charm that surrounds comics is their many multiple names. In France, they are called bandes dessinées [emphasis added] ( ... ). Comics [emphasis added], on the other hand, is what they are still called in the USA because of their inception at the beginning of the 20th century through humour. Funnies [emphasis added], on the other hand, fell out of favour, and since the 1980s and 90s, mainly due to Will Eisner, graphic novels and sequential art [emphasis added] have gained ground. In Japan, “the term manga can be traced back to the 18th century, and the Japanese artist Hokusai used it in 1814 to describe his books of ‘eccentric sketches’” (Gravett, 2006: 13). Notably, the word manga (without the accent) derives from the Chinese manhua [emphasis added], the term for Chinese manga today. Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea use the variation manhwa [emphasis added]. In Italy, comics are known as fumetti [emphasis added], literally “smoke”, alluding to speech balloons. In Spanish, historietas or cómics [emphasis added] are common terms, and tebeos is popular in Spain as a reference to the famous TBO magazine from 1917, like the word gibi in Brazil ( ... ). In Portugal, the term has shifted from histórias aos quadradinhos to the contemporary banda desenhada [emphasis added]. In Brazil, besides histórias em quadrinhos, the word gibi is also widely used, synonymous with moleque, negrinho stemming from Grupo Globo’s 1939 magazine that featured a black boy as its emblematic character on the cover. (pp. 32-33)

As Vargas (2015) mentioned, in Brazil, various terms and expressions are employed within the same context as comics to distinguish the different styles of production and publication. These classifications include “quadrinhos” (comics), “romance gráfico” (graphic novel), “zine”, or “arte gráfica” (graphic art), and they serve to specify the type of narrative one is reading. Since this article will specifically focus on graphic novels1, it is worth explaining that this is a specific classification of comics that has gained popularity in the publishing market due to its numerous production possibilities. Its designation in Brazil translates to graphic novels, used in the United States to categorise comic books - or comics - with literary traits in their production. However, much like the broader category of comics, graphic novels’ classification, origin, and definition are marked by ambiguity rather than clear-cut delineations:

there is no consensus regarding the emergence of graphic novels. In Spain in the 1940s, “novelas gráficas” [emphasis added] were romantic comics (García, 2012: 33). However, the term began taking on more significant artistic aspirations in American fanzines during the 1960s. In 1978, with A contract with God and its author, Will Eisner, came the real boost for this new terminology, which would gain popularity in the ensuing decades. In many interviews and his textbooks, Eisner has never hidden his idea that comics should be regarded as a form of literature when it comes to reading them, aligning with the perspective of the Spaniard Román Gubern in his book Literatura de la imagen [emphasis added], first published in 1974. The term romance gráfico [emphasis added], or graphic novel, lends comics a sense of literary nobility and takes comics off the newsstands and into bookshops, a trend that has notably evolved over the past two decades. Some critics have taken issue with this term, primarily due to its apparent strategy of elevating comics by associating them with culturally recognised literary traditions in “high culture” spaces. (pp. 33-34)

It should be noted that the genre of autobiography is quite prevalent within this particular category. Its defining characteristics, including a single narrative and creative autonomy, enable works with personal themes to break away from the conventions and artistic constraints typically associated with serialised publications. Contemporary themes challenge or diverge from the established norms of traditional publishing, and comics provide a welcoming space for exploring these ideas and the freedom of expression. As Santiago García (2010/2012), the author of A Novela Gráfica (The Graphic Novel), points out, the graphic novel fosters an “awareness of the author’s freedom” (p. 305), which may explain the abundance of autobiographical works in this medium.

Amaro Xavier Braga Jr. and Natania Nogueira (2020) have pointed out that topics concerning sexuality, race, class, and gender tend to be particularly prominent in graphic publications. This prominence is attributed to the unique possibilities offered by illustration, allowing narratives to extend into another form of language that can be shaped not only through written words but also through artistic expression. Moreover, the immediacy required for comic book narratives stems from their dynamic and straightforward reading experience. Consequently, the production of these narratives demands a more incisive approach.

Gender relations, sexuality and feminism have discovered, in this centuryold medium, a platform for expressing and depicting diverse tribes that emerged in Western and Eastern societies during the 20th century, incorporating social, political and behavioural aspects that mirror the changes and concerns fueled by the numerous social movements that characterised the 20th century and whose extensions continue to influence the 21st century. (Braga & Nogueira, 2020, p. 8)

Looking back to the second half of the 20th century, we can observe new narrative behaviours influenced by contemporary issues, specifically in North American productions. According to Alexandre Linck Vargas (2016), when some comic artists embraced a more anarchist and revolutionary discourse aimed at amplifying social demands and concerns, as well as breaking paradigms and provoking conservative political norms, comics intended for adult audiences became a countercultural product and were classified as underground2. “In the American experience, the highest level of authorship in comics is often linked with underground comics and the world of ‘alternative’ publications” (Vargas, 2016, p. 28). In other words, the production of underground comics, which emerged in the United States in the 1960s, was driven by eschewing norms, provocation, mockery and erotic themes - the latter being classified as comix. This movement gave rise to zines3, which remain very popular to this day, and for many artists, they are a form of apprenticeship at the start of their careers.

What may draw many authors to the graphic novel is also its flexibility, allowing them to break away from the standardised techniques of classic comic book illustration since its construction praises both the drawing and the narrative, incorporating elements of literature, strengthening the autobiographical possibilities and/or accounts of experience and testimony, as is evident in the object of study of this article. Despite major national publishers recognising the potential of this category and investing in it, the independent Brazilian graphic novel still offers a means to escape the financial constraints of publishing houses and the limitations imposed on the creative processes of comics. Moreover, it opens doors for artists who deviate from heteronormative standards to gain greater visibility.

This article analyses queer-themed comic publications, particularly the autobiographical work Monstrans: Experimentando Horrormônios by trans artist Lino Arruda (2021). This analysis will explore the traits and stylistic choices made by the author, who has chosen to represent himself through grotesque images. Additionally, it will examine other comic works within the same thematic scope - that contribute to debates about gender, sexuality and transsexuality, thus fostering the growth and development of the category itself and, by extension, our society, bearing in mind that “comics provide important insights into bridging gaps in our understanding of what human society was, what it is and what potential it has to become in the 21st century” (Braga & Nogueira, 2020, p. 12). To this end, we will use a methodology based on a compilation of literature from gender studies, comics, and art history.

2. Drawing Gender

Fortunately, in Brazil, the production of gender-themed comics has become more frequent, largely influenced by the work of the renowned Laerte Coutinho, a transgender cartoonist who found in her drawings a way to understand herself within her gender identity while shedding light on the peculiarities of trans experience for her readers. Notably, research on Laerte’s productions and its impact on gender studies has been conducted by Maria Clara da Silva Ramos Carneiro (2021) and Hadriel Theodoro (2016). Maria Clara Carneiro’s analysis focuses on Laerte’s body, portrayed in her comic strips as a staged transvestite body. She delves into how Laerte, through her characters Hugo and Muriel, has “created a constellation of characters, where her line and approach to humour function as signs or as boundaries between her body as Author and that of the other authors who inspired her” (Carneiro, 2021, p. 64). On the other hand, Hadriel Theodoro (2016) delves into the visibility of transgender experiences in the media, considering them as a form of consumption. He seeks to investigate “the intersections of the media visibilities of transgender people with how they permeate a political and citizen action aimed at legitimising their own existence, securing social recognition devoid of stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination” (p. 34). In the case of Laerte’s comics, his research aims to understand:

how Laerte’s experience can contain an interrelationship between production and consumption aimed at assigning visibility to transgender people; to determine whether the media portrayals of Laerte’s transness favour binary frameworks or the multidimensionality of transgender identities; and to understand how the experience of transness is constructed in the visibility policies derived from Laerte’s activist experience. (p. 35)

The character Hugo/Muriel, recognised as an allegory of Laerte’s gender transition, emerged at the beginning of the 21st century. Through a series of comic strips published in the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper and on the internet, the artist gradually developed the theme and drew her process, allowing us, her readers, to follow her phases of rediscovery. Vera Maria Bulla (2018), analysing some of the artist’s comic strips, notes that:

[the strips] can be seen as a form of self-understanding for the cartoonist who, while learning about gender issues, leverages her knowledge in the strips and spontaneously educates the reader, in a didactic and humorous manner, to learn with her about what it means to be transgender. Laerte’s method of sharing her discoveries serves as a way to educate the wider public to be more tolerant and potentially create opportunities for dialogues about respect and acceptance. (p. 32)

Laerte Coutinho’s comic strips about her gender transition delve into her desires, confidences and fears, permeated by plenty of humour and a good dose of irony, especially when the focus is on highlighting the shortcomings of hetero-cis-normativity in maintaining genders within a society still based on outdated binary guidelines.

Comic strips have the power to convey ideas and opinions in tandem with the themes they address. Studying Laerte’s comic strips to investigate how the process of discovering his own gender identity unfolded through his characters offers valuable insights by dispelling countless misinterpretations surrounding issues related to gender and sexuality. (Bulla, 2018, p. 47)

Laerte’s remarkable talent in comic production, coupled with her ingenuity and courage in opening up to the public, underscores the capacity of autobiographical narratives to thrive across diverse formats and various media. It is no coincidence that the emergence of a voice that resonates with many, employing both narrative and drawing as communication channels, has the potential to promote revelations and transformations in its surroundings by fostering debate on matters of identity and art. As comic artist Aline Zouvi (2020) remarked about the autobiographical space in queer comics:

this autobiographical space amplifies an identity narrative that doesn’t just concern its author but an entire community to which he belongs and with which they identify. The fusion of imagery and text provides, in addition to this narrative and discursive construction, the presence and visibility of the image. We might not realise it, but for the author and the LGBTQ+ audience, it is essential not only to read but also to see themselves drawn in the comics. Representativeness finds in autobiographical narratives the opportunity to advance discussions on gender identity and sexuality through the lens of comics. It is becoming increasingly important that we do not lose sight of this power, always striving, as authors or readers, for a production attuned to its social and cultural context but also committed to its artistic quality. (p. 16)

The autobiographical queer graphic novel can thus construct realities on the fringes of a social system that often excludes lives deviating from the norm. We can see, in various works of this specific nature, that the line, the drawing, the illustration, and, in short, the artistic aspect of the visual narrative embodies what the verbal narrative, constrained by speech ballons and subtitles, can merely suggest due to the opacity of language. Works of Brazilian artist Alice Pereira (2019), entitled Pequenas Felicidades Trans (Small

Trans Happinesses), and Italian artist Fumettibrutti (2022/2019), La Mia Adolescenza Trans (My Trans Adolescence), both autobiographies, explore similar plots while presenting distinct constructions. Alice Pereira (2019) approaches her gender transition process from an intimate and self-analytical standpoint through soft lines and colours and with touches of irony and caustic humour.

As noted by Maria da Conceição Francisca Pires (2021), Alice Pereira’s intention “was to illustrate how the widespread lack of knowledge, ignorance or refusal to acknowledge transgender issues contributes to reinforcing stereotypes, prejudices, stigmas and taboos” (p. 2). Fumettibrutti (2022/2019), on the other hand, exposes the violence and transphobia she suffered during her process directly and unashamedly, using strong colours and rustic features in a more realistic narrative. Here, visuals have the power to overcome blockages that try to hinder the rights and voices of many LGBTQIA+ lives. As noted in the article “Transmediality Against Transphobia: The Politics of Transsexual Self-Portraiture in Fumettibrutti’s Work Between Comics and Photography”, published by Nicoletta Mandolini. In both these works, it is possible to witness an interlocutor who embarks on a process of body complexion4 that can serve, as in Gloria Anzaldúa’s “autohistoria teoria” (self-writing theory; 2012), as a possibility of healing and subjectification. These narratives are not merely cathartic but crucial in exposing the truth and the lived experience.

3. Monsters and Horrormones

Lino Alves Arruda introduces his doctoral thesis, entitled Monstrans: Figurações (In)humanas na Autorrepresentação Travesti/Trans Sudaca5 (Monstrans: (In)human Figurations in Transvestite/Trans Sudaca Self-Representation) by posing the question “how are transvestite /trans experiences represented in contemporary culture (visual arts, literature, cinema, theatre, etc.)?” (Arruda, 2020, p. 15). Author, artist and comic book artist, Lino identifies as transmasculine and has a disability. He has dedicated his academic research to analysing his experience before, during and after his gender transition, as well as other LGBTQIA+ existences, in unison with his creative approach. In his thesis, Lino Arruda chose to introduce his work with several thought-provoking questions like the one above to prompt reflection on how several of today’s artistic manifestations. Although anchored (and here this word fits perfectly) in an initiative intended to embrace diversity, they may inadvertently support discourses that continue to uphold “identity cysthemes and are linked to the production of hegemonic knowledge, perspectives and subject positions” (Arruda, 2020, p. 15). His research bore fruit and a year after the presentation of his thesis, Lino published, with the support of the project Rumos Itaú Cultural - but still independently - the graphic novel Monstrans:

Experimentando Horrormônios, his autobiography in comics.

In this work, Lino Arruda recounts his childhood, adolescence and adulthood, focusing on the medical interventions he underwent as a child, the discovery of his sexuality and his reflections on his gender identity. When he draws himself, he uses free and shapeless strokes, sharing with the reader the perception of his image through the eyes of others and from his own perspective. The author dedicates his work as a comic book artist, both in this work and in zines published in other years6, to tackling themes such as transsexuality, everyday life, sexuality and visibility, which made his autobiography the account of the experience of a person who grew up under strong interventions and social judgements of policies on his body and compulsory attempts (internal and external) to standardise his image and identity. His research work has led him to dedicate his studies and artistic and cultural approaches to the trans and transvestite community, especially through the theme of monstrosity based on our Western culture, as a means of self-representation and expression, as he states:

the primary objective of this research is to identify, organise and analyse a self-representational, independent and countercultural transvestites/trans literary and imagery archive, aiming to create channels through which these dissident voices can engage in productive dialogues with others to reshape the mainstream symbolic repertoire. As such, dismantling the institutional systems that have consistently excluded transvestites/trans self-enunciations and self-representations is one of the prerogatives of this project, especially considering the exoticising and alienating imaginaries and discourses commonly found in the authorised sites of knowledge production about dissident subjectivities. (Arruda, 2020, p. 15)

Through his self-representation, Lino draws creatures that many would consider grotesque, sometimes reflected in the mirror, at times looking back at us, with the aim of re-signifying what exactly this “frightening” characteristic is, this monstrosity, which reflects social hypocrisy much more than how he sees himself. After all, we label as a monster something or someone not identified within standardisation, not reflected in the mirror of the so-called “ordinary”, which is demeaning and considered abject. The philosopher Julia Kristeva (1980) explored the concept of abjection in her work Poderes do Horror: Ensaio Sobre a Abjeção (Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection). She contended that the abject is what causes strangeness, shakes established foundations and threatens an existing order: in this sense, the trans existence exposes the failures of the social heteronormative system.

Abject. It is something rejected from which one does not part, from which one does not protect oneself as from an object. Imaginary uncanniness and real threat, it beckons to us and ends up engulfing us. It is thus not lack of cleanliness [propreté] or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite. (Kristeva, 1980, p. 4)

The horror of abjection described by Julia Kristeva is close to the representations of the female body in literature and cinema, when this body is also seen as abject, as we can interpret from Barbara Creed’s (2007) notes in The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. Drawing on Julia Kristeva’s essay (1980/?), she analyses how the representation of women in horror films involves abjection through the lens of masculinity.

The presence of the monstrous-feminine in the popular horror film speaks to us more about male fears than about female desire or feminine subjectivity. However, this presence does challenge the view that the male spectator is almost always situated in an active, sadistic position and the female spectator in a passive, masochistic one. (Creed, 2007, p. 7)

Although heteronormativity here is not directly challenged within a system of sexuality control, much of female representations in horror films permeates the narrative in which women are subjected to physical and/or psychological torment imposed by male characters, whether human or monstrous. The abjection of the female body is, therefore, constructed by misogyny. On this subject, philosopher Judith Butler, in an interview conducted by the Women’s Studies Department of the Utrecht University Arts Institute7 in the Netherlands, examines the concept of abjection and underscores that reimagining bodies can be seen as a pillar of feminism which is crucial for survival. She goes on to highlight that “the abjection of certain kinds of bodies, their inadmissibility to codes of intelligibility, does make itself known in policy and politics, and to live as such a body in the world is to live in the shadowy regions of ontology.” (Prins & Meijer, 2002, p. 157).

But back to Lino Arruda, why monstrosity? In fact, monstrosity has been a recurring theme in Western art since ancient times, with its roots in Homeric poems and heroic epics. Mythical creatures like cyclopses, sirens, and three-headed monsters are fanciful creations that often played the roles of tormentors in literary adventures filled with moral lessons and symbolic meaning. However, as pointed out by Ana Soares (2018), monsters are not confined solely to the realm of imaginative literature, nor are they always cast in antagonistic roles. In analysing the subject, Soares states that monstrosity - or, as she calls it, “the monstrous” - is a concept that permeates our culture and extends beyond the realm of imagination and creative storytelling. It serves as a representation of the fear of the unknown or a challenge to reason:

monsters are not just the product of abstract imagination, nor is their existence expressed only in verbal discourse: their incarnations in graphic pictorial images are many and go back a long way. They didn’t just emerge with technological sophistication (such as cinema). In fact, some of the monsters with the most extensive graphic representations in 16th-century illustrations can be traced back to texts from the 5th century BC. Monsters’ discursive expression and visual counterparts are not new, nor were they only discovered during the age of European exploration and contact with their neighbours. The etymology of “monster” seems to be associated with the Latin verb “moneo”, which means “to warn”. In some way, therefore, when referred to this way, monsters convey a signal, usually of some fear, negative or threatening event. (Soares, 2018, p. 55)

Ana Soares (2018) delves deeper into her discussion by reflecting on what it is about the monster that fascinates the human who created it and concludes that the monstrous is something intimately connected to humanity since “the monstrous, after all, is human like us” (p. 56). For the author, the wellspring of the creation of the monsters that haunt and terrify humans is the realm of reason, unique to us human beings, considered rational and thinking animals. These qualities set us apart from what might be deemed abominable.

The monstrous resides within us whenever we contemplate it. Wherever we are, it is always nearby and far from exotic. It is initially described as the dehumanised, the sub- or super-humanised. Its constitution in literature (...) is formed by emphasising the differences that set it apart from those who describe it, from the writer - from humanity, thus, from a non-monstrosity of the writer. Nevertheless, since they are solely generated in human thought, monsters are, after all, as human as we are by their very essence (Soares, 2018, p. 66)

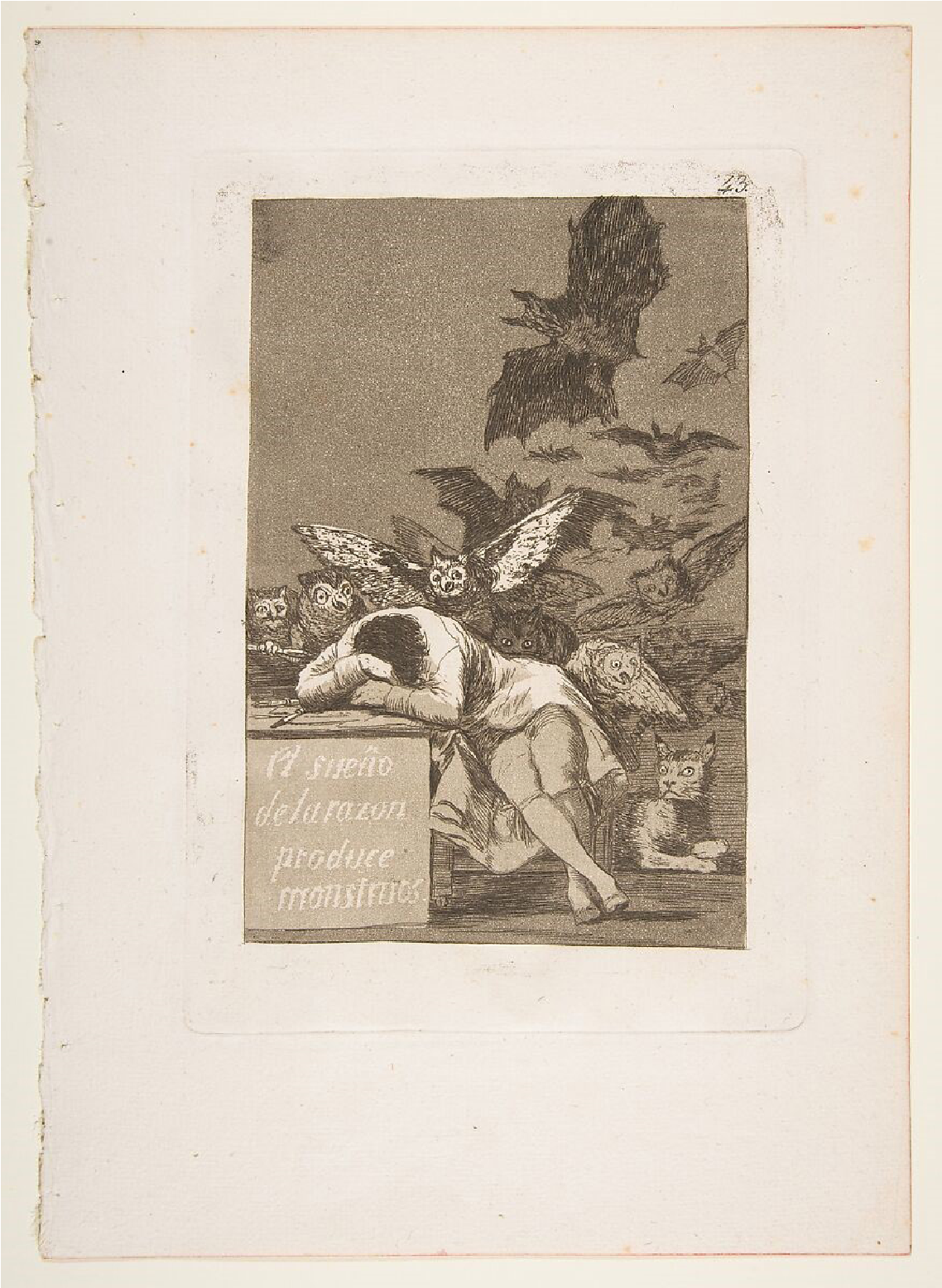

In an etching by the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, from 1799, reason is seen as the very creator of monstrosity. The etching, known as Plate 43 (Figure 1), is part of the collection “Los Caprichos”8 and reads “the sleep of reason produces monsters”:

Source. From “Plate 43 from “Los Caprichos”: The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (El Sueño de la Razon Produce Monstruos)”, by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, s.d. (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/338473). Public Domain

Figure 1 Los Caprichos, Plate 43

Goya was a harsh social critic. Plate 43 was the artist’s attempt to prompt Spain’s social and intellectual strata to pay closer attention to the relevant events of his time, which involved political issues between the country and France (Soares, 2018). In this case, the monstrosity, represented by animals flying over the figure of a man lying at a table at which he was apparently writing, conveys the representation of what could emerge the moment reason succumbs:

the caption itself induces ambiguity in the interpretation: the Castilian word “sueño” can either mean the “sleep” of reason (in other words, the moment when reason allows itself a moment of peace and man is dominated by the non-rational) or it can be the “dream” of reason, symbolising a projection or longing, which would be the fruit of the human capacity to create ideas, or the outcome of a state of vigilant production in which monsters are generated. In either interpretation, for Goya, even when represented outside what is physically human, the monstrous is born of that and may even be born from the most human of qualities: reason. (Soares, 2018, p. 55)

Indeed, the representation of monstrosity in the arts has long been a means of questioning human behaviour and rationality, as well as humanity’s ability to create and be dazzled by the unknown, fascinated by what is new, and at the same time, being enthralled by monstrosity can be nothing more than a reflection of what human reason itself is when it is free or at rest.

So, how can monstrosity be autobiographical? Before introducing this explanation, it is worth mentioning that the graphic novel Monstrans: Experimentando Horrormônios, before its completion and publication as a complete work, emerged through the publication of one of the zines authored by Lino Arruda (2020): “combining illustrations and autofictions, Monstrans: experimentando horrormônios is a chapter-zine in which I embark on the non-human in autobiographical representations to recount my transmasculine experiences of unintelligibility” (p. 19). Lino emphasises when talking about this chapter-zine in his thesis that the monstrous subjectification he uses in his illustrations can disrupt the norms that define what representation and reality are, pushing aesthetics beyond the human realm and into the territory of monstrosity, a recurring theme in the theoretical framework of his research into dissident artistic productions in a decolonial context (Arruda, 2020). He goes on to say that the classic image of the monster (werewolf, Frankenstein, or even an animal/human hybridism) used in his illustrations takes up agendas that persisted in Brazil since the colonial period, which associated transvestite/trans existences with animality.

Throughout history, the conception of monsters has been associated with identity disorientation, evident in various cultures, religions, and literature, as João Carlos Firmino Andrade de Carvalho (2018) states:

the monster, in order to be a monster, in the full sense of the word/concept, must reside on that boundary between existence and non-existence, between the possible and the impossible, paralysing and enrapturing the human being’s gaze at something unique and unrepeatable and showing them not so much what they are not, but a singular alternative possibility of existence. (p. 39)

This non-place of belonging can also be related to the dissociation of human identity that transvestites/trans people suffer from a society that denies citizenship, dignity and human rights to such experiences: “the problem posed by the monster is therefore that of the dialectic of identity and difference, or, to put it another way, that of the limits of man’s humanity” (Carvalho, 2018, p. 40).

Philosopher Paul B. Preciado (2021) also uses the idea of the monster as a reference to his existence as a non-binary body in his speech “Eu Sou o Monstro que Vos Fala” (Can the Monster Speak?). This speech was written by Preciado in 2019 to be read by him at the “International Conference” of the School of the Freudian Cause, when he was invited to speak at a psychoanalysis conference at the Palais de Congrès in the French capital, Paris. As it turned out, the philosopher could not finish reading his speech because he was booed, offended and ridiculed by the 3,500 psychoanalysts who were meeting to discuss the topic of “women in psychoanalysis” and who did not accept the speaker’s questions:

the speech triggered an earthquake. When I asked whether there was a psychoanalyst in the auditorium who was queer, trans or nonbinary, there was silence, broken only by giggles. When I asked that psychoanalytic institutions face up their responsibilities in response to contemporary discursive changes in the epistemology of sexual and gender identity, half the audience laughed and the other half shouted or demanded that I leave the premises. One woman said, loudly enough that I could hear her from the rostrum: “We shouldn’t allow him to speak, he’s Hitler”. Half the auditorium applauded and cheered. The organizers reminded me that my allocated time had run out, I tried to speed up, skipped several paragraphs, I managed to read only a quarter of my prepared speech. (Preciado, 2021, pp. 278-279)

Preciado (2021) dedicated the publication of the full speech to Judith Butler. In the more than 50 pages of his account, we can understand how mistakenly the psychoanalytical class can influence the widespread perception of trans experiences by pathologising gender and sexuality, attributing them to mental illnesses and biological disorders:

I, a body branded by medical and juridical discourse as “transsexual”, characterized in most of your psychoanalytic diagnoses as a subject of an “impossible metamorphosis”, find myself, according to most of your theories, beyond neurosis, on the cusp of - or perhaps even within the bounds of - psychosis, being incapable, according to you, of correctly resolving an Oedipus complex or having succumbed to penis envy. And so, it is from the position assigned to me by you as a mentally ill person that I address you, an ape-human in a new era. I am the monster who speaks to you. The monster you have created with your discourse and your clinical practices. I am the monster who gets up from the analyst’s couch and dares to speak, not as a patient, but as a citizen, as your monstrous equal. (p. 281)

At various points in his speech, the author states that he prefers his new condition as a “monster of modernity” (Preciado, 2021, p. 317), as perceived by psychoanalysis, over attempting to cage himself within the binary condition of the cisgender world. For him, to exist within the experience of this monster is to be able to belong to an unexplored universe. As we can also see in Lino Arruda’s graphic novel in the moments when his shapeless identity is represented, transsexuality is a dynamic state; it is an ongoing process that unfolds throughout one’s lifetime, one that defies the norms ingrained in a system of control precisely because it acts in a manner that transcends conventions: “the monster is one who lives in transition. One whose face, body and behaviours cannot yet be considered true in a predetermined regime of knowledge and code - the code may be a language, a power” (Preciado, 2021, p. 296). This is probably the inspiration for the title Monstrans.

The hormonal changes associated with gender transition, the derogatory social stigma on dissident bodies, discovering a new body and searching for remnants of what no longer exists are themes of many independent productions and have provided readers with a sense of identification and recognition9. Bringing the narrative closer to the reality of those who consume autobiographical works on these themes shows that different experiences are animalised by the (cis)theme (Arruda, 2020).

This representational artifice has become more prevalent in contemporary countercultural media (such as zines, booklets and other autonomous literary materials), especially in projects aiming to challenge the observer (by using the figure of a body that quickly and intuitively generates identification) and, at the same time, circumvent the burden of compulsorily evoking an identity unit through the representation of the body. (Arruda, 2020, p. 26)

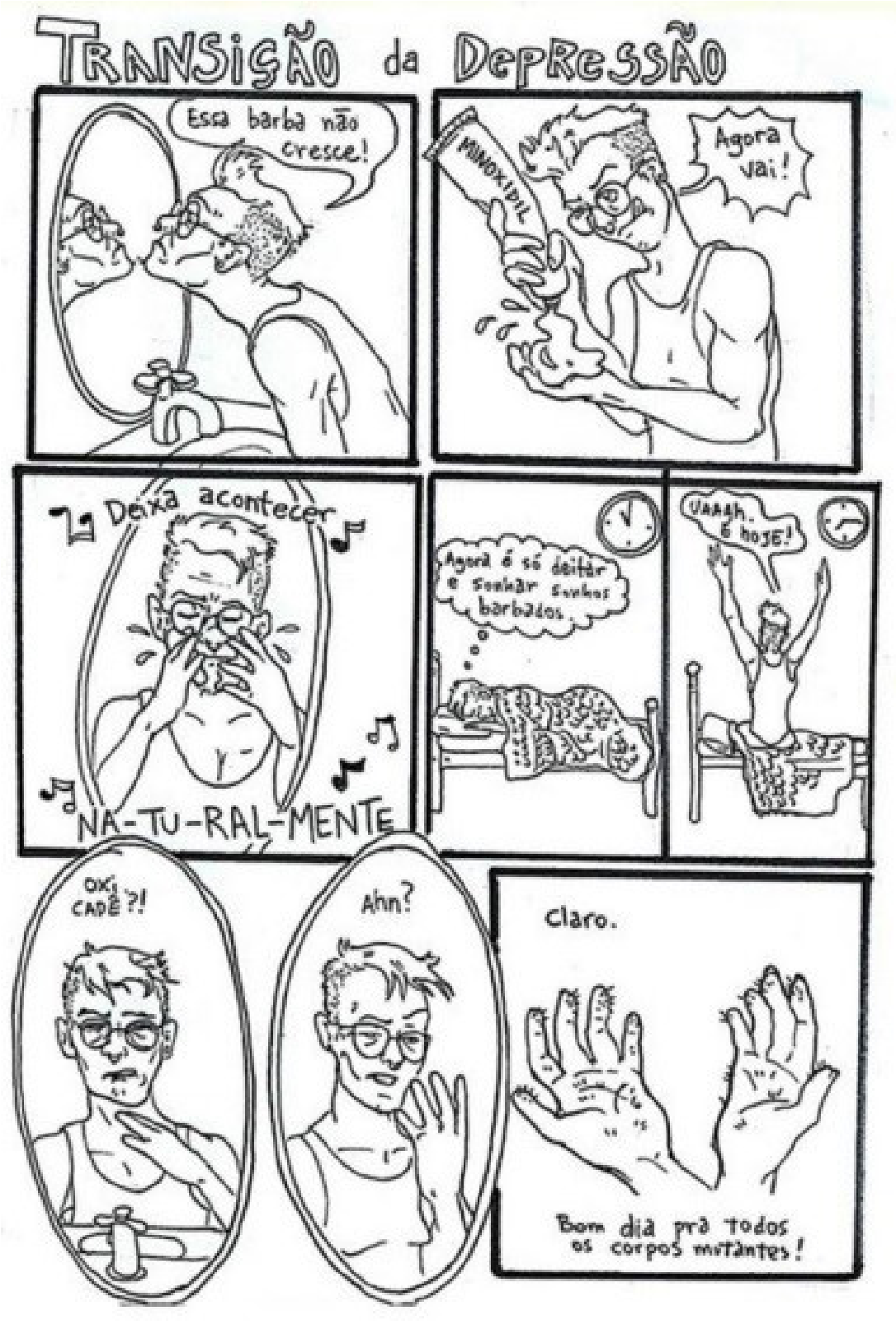

Lino Arruda also notes that instead of fighting to get out of a marginal or underground label, queer graphic publications prefer to embrace the chaos and assume the failure inherent to heteronormativity itself since, for there to be success on one side, there always needs to be failure on the other. Therefore, if such publications show a loss of human identification, linguistic standardisation, control of bodies, among others, it is because of a resistance movement that, by assuming failure, allows the transvestite/ trans counterculture to take the power of its time and space upon itself, re-signifying its identity through the exposure of monstrosity, as we can see in the comic below by Lino Arruda, published in one of his zines (Figure 2).

Source. From Monstrans: Figurações (In)humanas na Autorrepresentação Travesti/ Trans Sudaca, by L. A. Arruda, 2020, p. 38. Copyright 2020 by UFSC.

Figure 2 Zine Quimer(d)a, Number 2, 2017

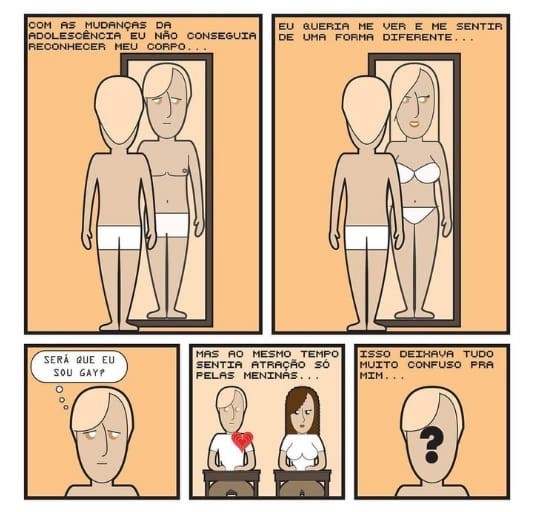

The accounts of the gender transition process in comics, such as those in the picture above, have a common element relevant to our discussion since it is always present when the artist is self-reflected during the narrative: the mirror. The mirror in Monstrans: Experimentando Horrormônios (2021) is much more than a scenographic feature. This device allows the reader to follow Lino Arruda’s self-reflective process about his identity, gender transition and the transformative effects of hormonal chemical processes that damage his skin. Moreover, the mirror is also present in moments of his childhood and adolescent memories as an object that exposes what is out of place. However, later, it also serves the function of confrontation, the search for understanding and identification. In his narrative, Lino illustrates how, during his childhood and adolescence, he realised that there was a body in the mirror’s reflection that was not in its ideal space, in its place of truth. Lino’s change in behaviour towards the object over time is clear: before, he was a confused child apprehensive in front of his reflection, even turning his back on it; later, an individual contemplating the changes with a new perspective, one of admiration and discovery, ultimately leading to self-knowledge. In front of the mirror, monstrosity takes shape in Lino’s eyes, making him see what is extraordinary where others project abjection.

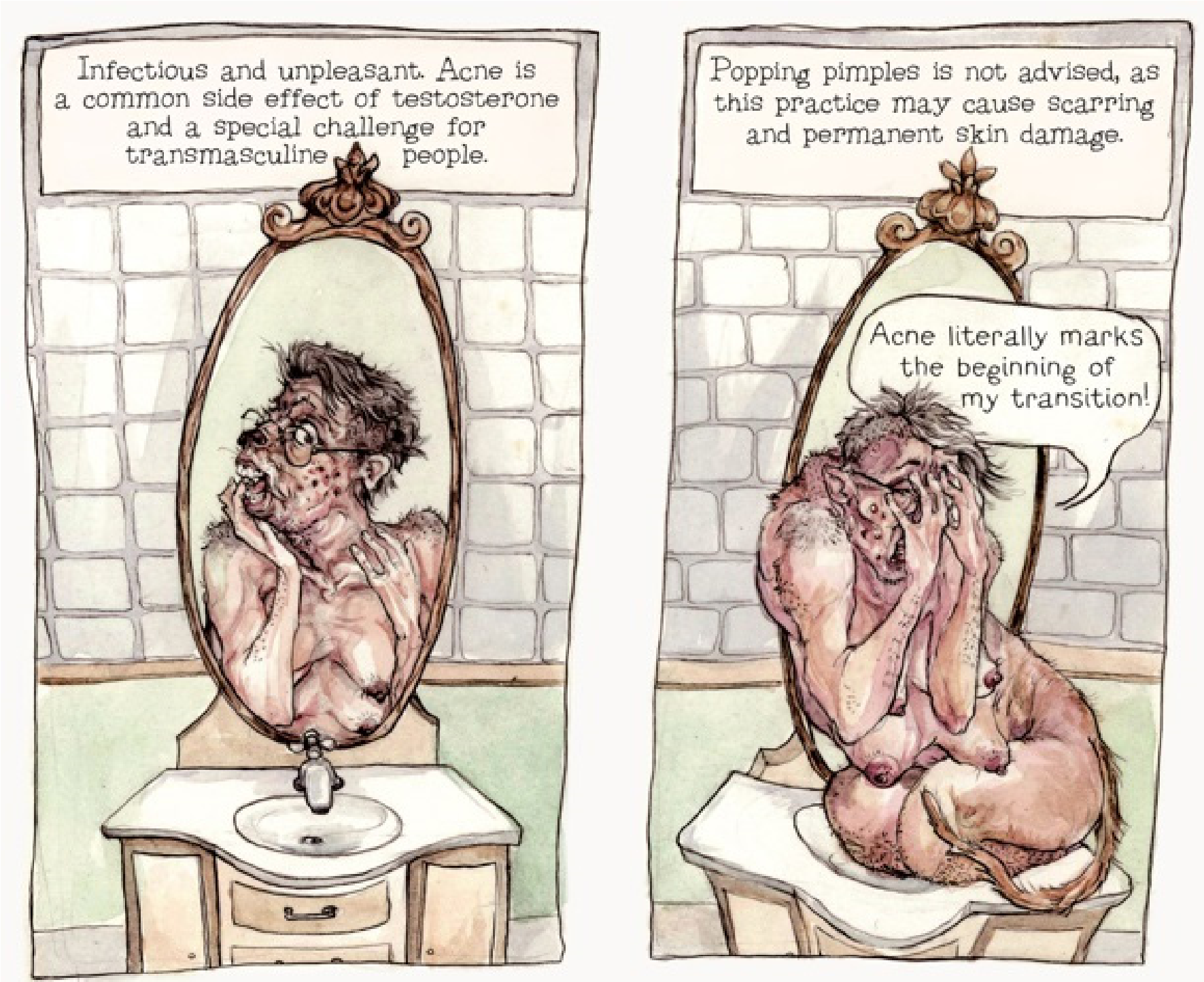

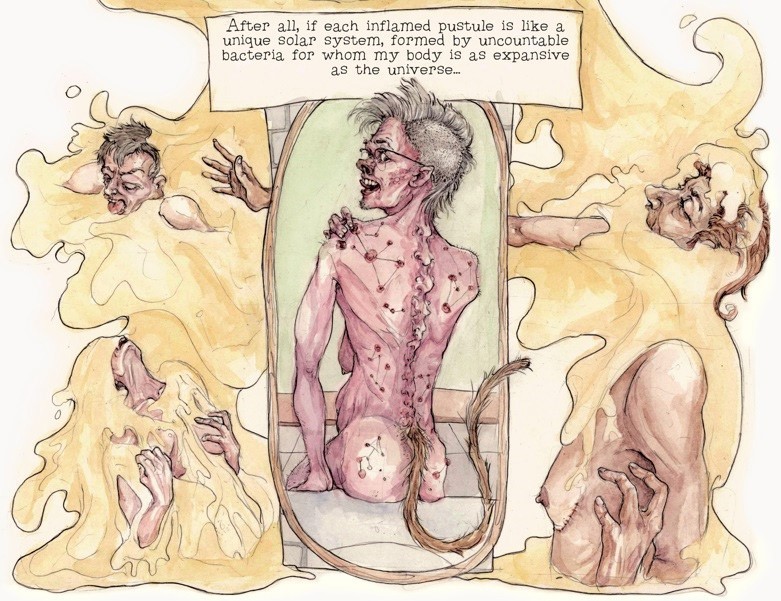

The book’s introduction begins with the author gazing into the mirror, inviting the reader to join him in reflecting on the consequences of undergoing hormone treatment with testosterone: acne rashes, oiliness, and scarring, among others. In Figure 3, we can see that this dialogue is with us, as Lino first draws himself looking outside the frame, outside the work, demonstrating the drawing’s ability to establish a direct and tangible connection with the recipient. That is made clear in the first picture, where the reflection faces us, and yet there is nobody in front of it, which is more evident in the second picture when the monstrous creature has its back to the mirror and faces us. Here, we see a transformed naked body with four breasts and a tail, a snout and lots of hair. The selfrepresentation constructed in this introduction aims to reflect on the changes caused by the hormones and how Lino feels as he goes through this process - the process of monstrosity - as well as the new precautions he must learn to take to and prevent the treatment’s side effects from becoming permanent.

Source. From “Introdução”, by L. A. Arruda, 2021, Monstrans: Experimentando horrormônios, p. 6. Copyright 2021 by Lino A. Arruda.

Figure 3 About acne

In Figure 4, the hybrid creature in the mirror turns its attention to itself, closely analysing its appearance through a magnifying glass. It now engages the readers through this object, drawing them into its self-examination, thus creating a third perspective - ours - in its self-analysis. Lino then teaches us that the complexities of the damage caused by acne go beyond the skin’s surface. He explains that since inside the pimples, living in the pus, there are bacteria that can proliferate and generate further infections. Based on this information, the introduction of the work also serves as a reflection, making Lino contemplate the life that resides inside him and how it is part of his body and his transition. Despite the potential harm, these bacterial lives emerged when he began his transition, making them part of the process.

Source. From "Introdução", by L. A. Arruda, 2021, Monstrans: Experimentando horrormônios, p. 6. Copyright 2021 by Lino A. Arruda.

Figure 4. Acne under the magnifying glass

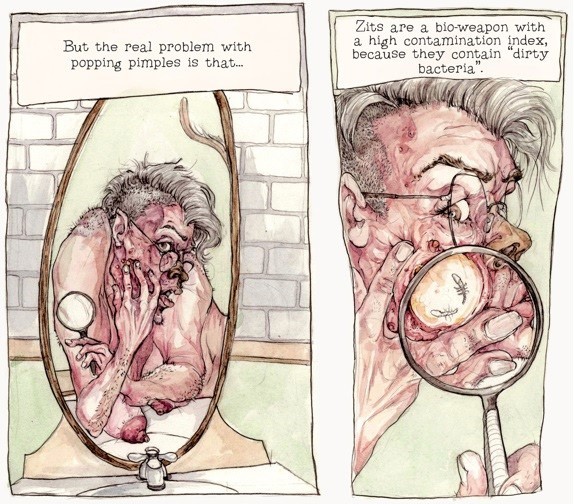

As such, Lino Arruda embraces the possibility of perceiving the less pessimistic side of interpreting his transition process and marvels at what his body can create, as we can see in Figure 5.

Source. From "Introdução", by L. A. Arruda, 2021, Monstrans: Experimentando horrormônios, p. 6. Copyright 2021 by Lino A. Arruda.

Figure 5 Acne acceptance

In Chapter 1, titled “Conversion Therapy”, Lino Arruda delves into his childhood memories and the time when, while struggling with his doubts about discovering his sexuality, he underwent painful physiotherapy treatment due to his physical disability. The author tells us that during her pregnancy, his mother was involved in a car accident that caused an injury that affected the development of his spine and lower limbs. So, from an early age, Lino has had to deal with a body that does not conform to the standards demanded by society. Little did he know this would be just the first of many medical and invasive processes he would have to endure. In an interview with Revista Mina de HQ in 2022, Lino says that in Monstrans, he tried to address all possible manifestations of his body and how it finds itself in society, surrounded by the labels assigned to him immediately after birth:

in Monstrans, I wanted to explore those moments of convergence between being trans, being disabled, being born visibly disabled and visibly masculine, with a visibly crooked gender. It’s one of the moments when the discourses are very different, like the medical discourse: this idea that I was born trans or that I was born “in the wrong body”. These are convenient discourses that ultimately serve the purpose of trying to “fix the body” or make it “the right body”. (Vitorelo, 2022, p. 34)

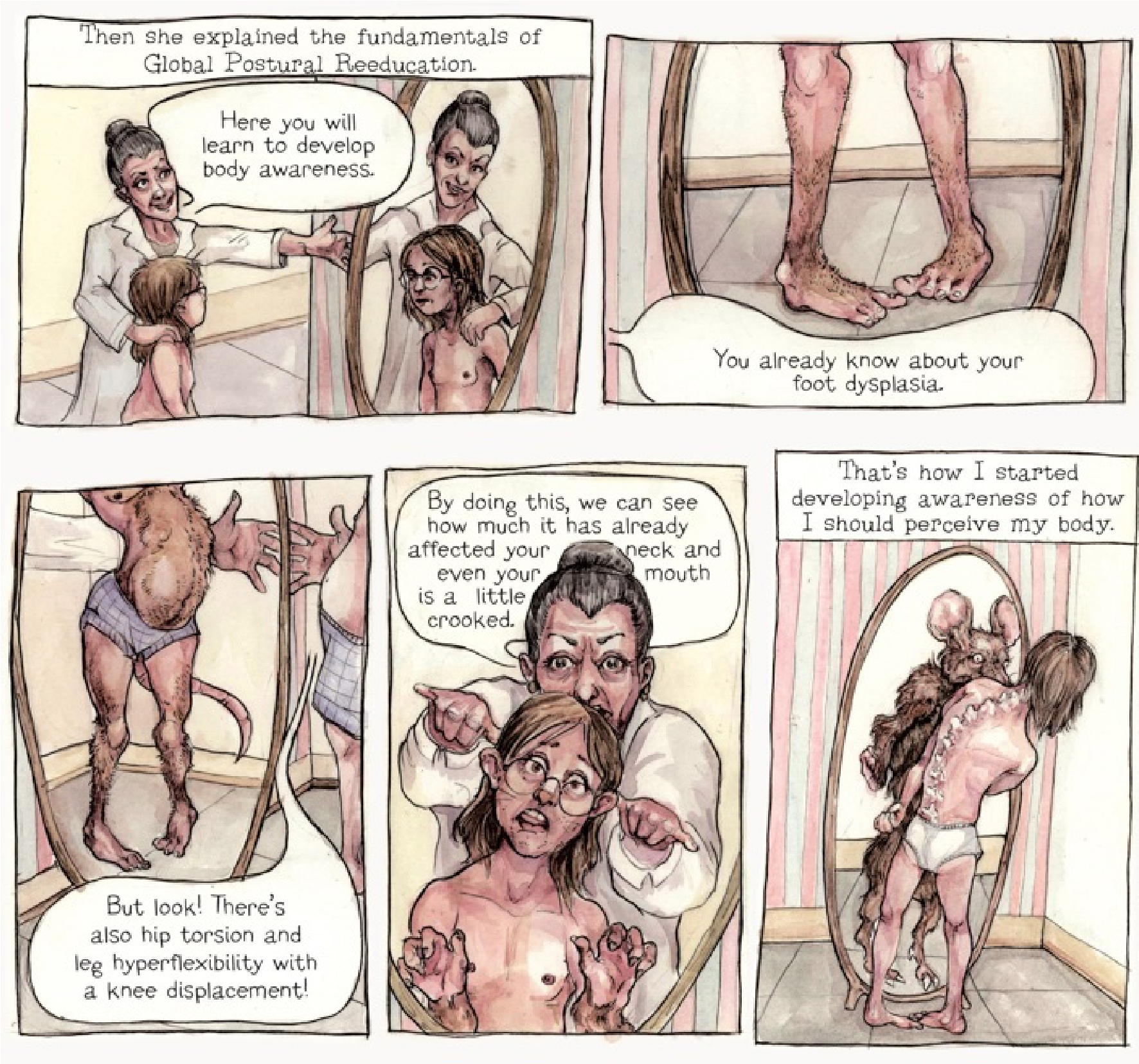

The title of this chapter takes us back to the conversion therapy for homosexuality, the so-called “gay cure”, advocated by conservative extremists who believe it is possible to cure homosexuality as if it were a disease, making individuals heterosexual. As such, the title serves as a pun on the fact that physiotherapy sessions would also be a way of converting his divergent body, as he narrates in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Source. From “Terapia de Conversão”, by L. A. Arruda, 2021, Monstrans: Experimentando horrormônios, p. 22. Copyright 2021 by Lino A. Arruda.

Figure 6 The physiotherapy

Source. From "Terapia de Conversão", by L. A. Arruda, 2021, Monstrans: Experimentando horrormônios, p. 39. Copyright 2021 by Lino A. Arruda.

Figure 7. Medical Interventions

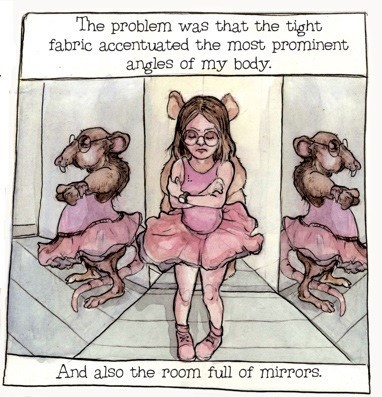

The physiotherapy process, intended to “fix” Lino’s body, helps the author contemplate his image and see the monstrosity he will later explore as the power of his existence. However, like any process of change and discovery, it is not only slow but also painful, both physically and emotionally, especially for a child trying to understand their peculiarities through the indolent discourse of medicine. Therefore, until the moment of self-awareness, Lino faces an inner battle and, for a while, the mirror, this object that unveils his raw truth, becomes a source of discomfort. In Figure 8, we witness a moment in the narrative when Lino tells us he was enrolled in a ballet school to work on his spine and posture alignment. However, for the author, being in a studio surrounded by mirrors only worsened his relationship with his image.

Source. From “Terapia de Conversão”, by L. A. Arruda, 2021, Monstrans: Experimentando horrormônios, p. 25. Copyright 2021 by Lino A. Arruda.

Figure 8 The room of mirrors

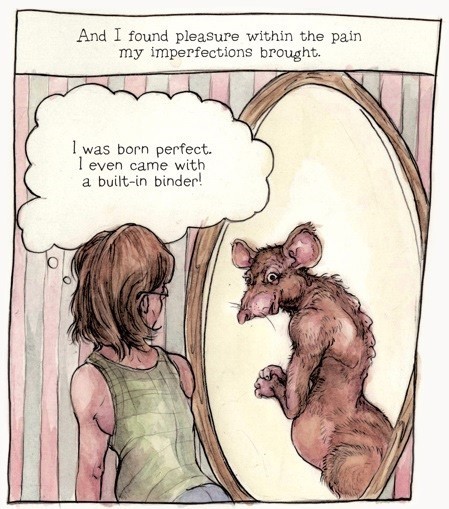

Over time, Lino’s relationship with the mirror evolves from annoyance to contemplation, as the object accompanies the author’s transformation and becomes an instrument of study and self-discovery. In Figure 9, we can see that Lino starts to grasp the nuances of his image and the distinctive qualities of his body that make him unique, as if, at this stage, he began to embrace monstrosity and interpret it as a metaphor for his self-representation.

Source. From “Terapia de Conversão”, by L. A. Arruda, 2021, Monstrans: Experimentando horrormônios, p. 40. Copyright 2021 by Lino A. Arruda.

Figure 9 A new vision

The use of the mirror in an autobiographical comic book narrative has the powerful ability to allow us, as readers, to witness the process of self-knowledge in motion, narrated as it happens or as a recollection. Whether used for contemplation or confrontation, the mirror peels away the layers of illusion we may have constructed about our image, revealing reality even if it is open to our interpretation. Revisiting Vera Bulla’s article (2018), the researcher also highlighted the significance of the mirror in her analysis of Laerte Coutinho’s comic strips. In these strips, Hugo is sometimes depicted interacting with his own reflection while dressed as Muriel, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Source. From “Capítulo”, by L. Coutinho, 2005, Hugo Para Principiantes, p. 49. Copyright 2005 by Editora Devir.

Figure 10 Hugo, standing before the mirror

For the author: “we can then consider that Hugo sees his feminine beauty in the mirror and admires a new way of showing himself to the world, glimpsing a new possibility, contemplating it while observing his reflection in the mirror” (Bulla, 2018, p. 39). This suggests that this could be another function of the mirror object, the glimpse of an expectation, as we can see in Alice Pereira’s comic (2019; Figure 11).

Source. From “Capítulo”, by A. Pereira, 2019, Pequenas Felicidades Trans, p. 9. Copyright 2019 by Edição da Autora.

Figure 11 Pequenas Felicidades Trans

Through the reflection, the narrative can also be constructed from a futuristic perspective, as the mirror in an illustration can offer a glimpse of the artist’s vision of selfrepresentation and what he imagines the end of his process might be. As such, we can understand that Lino Arruda’s relationship with the mirror constantly evolved during his maturing phase. The monstrous vision, which generated confusion and even shame, became a monstrous vision that fascinates and seduces.

4. Conclusion

The use of monstrosity as a resource for self-representation in the graphic novel Monstrans: Experimentando Horrormônios may disappoint readers expecting a story about overcoming a disability, the challenges of discovering transsexuality or even a transsexual man’s image disorder. On the other hand, Lino Arruda, frustrates all those mistaken expectations when he provokes us with his boldness and attitude by proudly drawing himself shapeless and in visceral tones as he explores the study of his body, his image and his technique.

At every transformation observed in the mirror or depicted on the physiotherapy table, Lino is one step ahead of those who anticipated an LGBTQIA+ narrative with a tragic beginning, with pre and post-gender transition moments leading to a happy ending. Instead, for the author, each painful or challenging moment he narrates and draws is part of reflecting on the events that have marked his life and proved crucial to his development. That is why Monstrans wraps up neatly; it avoids romanticising suffering and prompts readers to confront it candidly and directly without beating around the bush or lamenting. On each page, the child, teenager and adult that is Lino Arruda learns from the setbacks he faces, the mistakes he makes and the obstacles that stand in his way, showing the evolution of his personality and self-awareness, making his journey the primary focus of the plot.

Works like Lino Arruda’s, deviate from portraying marginalised existences as tragedies, offering a chance to perceive that experiences beyond heteronormative societal norms and aesthetic conventions are not exceptions but simply additional ways of coexisting within society. However, we still have a long way to go when it comes to approaching transvestite/trans themes in any media, be it comics, literature, cinema, television, among others. These experiences persist on the periphery of an oppressive standardising system. Artists such as Laerte Coutinho and Lino Arruda, as influential voices in their spheres, contribute to paving the way for other narratives to emerge and be heard, or in this case, read and contemplated. Lino’s portrayal of monstrosity is an act of reclaiming his self-image. It becomes an action to re-signify perspectives, both his own and those of the society that condemns him. He harnesses the power to convert prejudice and transphobia into inspiration for his art. As he highlighted in his doctoral thesis, this movement also happens in other artistic manifestations.

The graphic novel can be seen as a welcoming category for dissent since its characteristics can be attractive to free creativity and productive independence, beckoning artists looking for a democratic and liberating space to go beyond the forms of more traditional comics. Despite the financial and personal obstacles that stand in the way of those who strive for freedom of expression, the graphic novel’s growth in Brazil has been notably positive. Artists like Lino Arruda, who explore queer themes in their work, will always endure a challenging journey in advocating for the right to exist. It falls on us, readers, funders, researchers, and enthusiasts of the ninth art, to pursue this hopeful endeavour, fostering an environment where more artists can emerge daily, bolstering resistance and advocating for LGBTQIA+ experiences.

REFERENCES

Anzaldúa, G. (2012). Borderlands/La Frontera: The new mestiza. Aunt Lute Books. [ Links ]

Arruda, L. A. (2020). Monstrans: Figurações (in)humanas na autorrepresentação travesti/trans sudaca [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina]. Repositório Institucional UFSC. https:// repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/216221 [ Links ]

Arruda, L. A.(2021) Monstrans: Experimentando horrormônios. Edição do Autor. [ Links ]

Braga, A. X. Jr., & Nogueira, N. A. S. (2020). Gênero, sexualidade e feminismo nos quadrinhos. Editora Aspas. [ Links ]

Bulla, V. M. (2018). Tirinhas, alívio cômico e a identidade de gênero em transição: Hugo e Muriel no mundo imaginário de Laerte. Transverso, 6(6), 31-52. [ Links ]

Carneiro, M. C. S. R. (2021). O corpo em tiras: Ficções e autoficções transgêneras nas tiras de Laerte Coutinho. Revista Brasileira de Literatura Comparada, 23(44), 62-77. https://doi. org/10.1590/2596- 304x20212344mcsrc [ Links ]

Carvalho, J. C. F. A. (2018). Estranhas e admiráveis singularidades da natureza - Alguns exemplos (séculos XVI-XVIII). In J. C. F. A. Carvalho & A. A. S. Carvalho (Eds.), O monstruoso na literatura e outras artes. Centro de Literaturas e Culturas Lusófonas e Europeias. [ Links ]

Coutinho, L. (2005). Hugo para principiantes. Editora Devir. [ Links ]

Creed, B. (2007). The monstrous-feminine: Film, feminism, psychoanalysis. Routledge. [ Links ]

Fumettibrutti. (2022). Minha adolescência trans. Editora Skript (A. Braga; M. S. Rodrigues, Trad.). (Trabalho original publicado em 2019) [ Links ]

García, S. (2012). A novela gráfica (M. Lopes, Trad.). Editora Martins Fontes. (Trabalho original publicado em 2010) [ Links ]

Jaquet, C. (2014). Les ~transclasses, ou la non-reproduction. PUF. [ Links ]

Kristeva, J. (1980). Poderes do horror: Ensaio sobre a abjeção (A. D. S. Sena, Trad.). Éditions du Seuil. [ Links ]

Mandolini, N. (2022). Transmediality against transphobia: The politics of transsexual self-portraiture in Fumettibrutti’s work between comics and photography. New Readings, 18, 88-108. https://doi. org/10.18573/newreadings.121 [ Links ]

Moreau, D., & Machado, L. (2020). História dos quadrinhos: EUA. Editora Skript. [ Links ]

Pereira, A. (2019). Pequenas felicidades trans. Edição da Autora. [ Links ]

Pires, M. C. F. P. (2021). Transexualidade em quadrinhos: Narrativa autobiográfica nas histórias de Sasha, a leoa de juba e Alice Pereira. Anos 90, 28, 2-21. https://doi.org/10.22456/1983-201X.110580 [ Links ]

Preciado, P. B. (2021). Eu sou o monstro que vos fala (S. W. York, Trad.). Cadernos PET de Filosofia, 22(1), 278-331. https://doi.org/10.5380/petfilo.v22i1.88248 [ Links ]

Prins, B., & Meijer, I. C. (2002). Como os corpos se tornam matéria: Entrevista com Judith Butler. Ponto de Vista: Revista de Estudos Feministas, 10(1), 155-167. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-026X2002000100009 [ Links ]

Soares, A. I. (2018). Demasiado humano - A familiaridade do monstro. In J. C. F. A. Carvalho & A. A. S. Carvalho (Eds.), O monstruoso na literatura e outras artes. Centro de Literaturas e Culturas Lusófonas e Europeias. [ Links ]

The Metropolitam Museum of Art. (s.d.). Plate 43 from “Los Caprichos”: The sleep of reason produces monsters (el sueño de la razon produce monstruos). Retirado a 1 de julho de 2023 de https://www.metmuseum. org/art/collection/search/338473 [ Links ]

Theodoro, H. (2016). Visibilidades midiáticas e transgeneridade: Apontamentos sobre um estudo de caso com Laerte Coutinho. Revista Dito Efeito, 7(11), 30-42. https://doi.org/10.3895/rde.v7n11.5016 [ Links ]

Vargas, A. L. (2015). A invenção dos quadrinhos: Teoria e crítica da sarjeta [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina]. Repositório Institucional UFSC. https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle/123456789/135497 [ Links ]

Vargas, A. L. (2016). A invenção dos quadrinhos autorais: Uma breve história da arte da segunda metade do século XX. História, Histórias, 4(7), 25-37. https://doi.org/10.26512/hh.v4i7.10924 [ Links ]

Vitorelo. (2022). A monstruosa potência de ser trans. Revista Mina de HQ, (3), 33-35. [ Links ]

Zouvi, A. (2020). O espaço autobiográfico nos quadrinhos queer brasileiros. In E. Irineu, G. Borges, & G. Smee (Eds.), Quadrinhos queer (pp.15-17). Editora Skript. [ Links ]

1In this article, the chosen work for analysis will be referred to as a “graphic novel” to underscore its narrative attributes, with the term “comics” being used to encompass the broader category.

2“The term underground may have been coined by Time magazine, initially referring to Andy Warhol’s films and later to the newspapers popping up at the time. As comics appeared in newspapers, they earned this nickname” (Moreau & Machado, 2020, p. 441).

3Zines are low-cost editorial productions to publish and disseminate independent content, usually encompassing illustrations, poetry, manifestos and a diverse range of topics, and can be distributed for free or not. They can be published privately or collectively, depending on their purpose. Very present in the punk movement in the United States, they soon took over the world because they were low-budget productions that could be easily acquired, albeit clandestinely. In Latin America, the production of zines remains fairly common, but in Brazil, it was especially prominent in literary circles during the time of the so-called “marginal poetry”.

4The concept of “complexion” refers to the complexity of the social injunctions each individual carries. As Chantal Jaquet (2014) elaborates, the complexion comprises multiple dimensions (such as gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, etc.) that overlap and interact to shape individual trajectories. The complexion is dynamic and can change over time as new social injunctions are incorporated, or old ones are abandoned.

5The “term is a pejorative label used to refer to Latin America and its inhabitants. It gained prominence, particularly in the Spanish context, during the waves of migration in the 1990s, intending to address Latin American immigrants negatively. In this work, the appropriation of this terminology aims to evoke xenophobic/racial tensions and re-signify its original use and meaning” (Arruda, 2020, p. 15).

6They are: Sapatoons (2011); Anomalina (2013); Quimer(d)a #1 (2015); Quimer(d)a #2 (2018) e Peitos (2018). Learn more at https://www.linoarruda.com.

7Originally published as “How Bodies Come to Matter: An Interview With Judith Butler” in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society in 1998 by The University of Chicago Press.

8“This is the best known image from Goya’s series of 80 aquatint etchings published in 1799 known as ‘Los Caprichos’ that are generally understood as the artist’s criticism of the society in which he lived. Goya worked on the series from around 1796-98 and many drawings for the prints survive. The inscription on the preparatory drawing for this print, now in the Prado Museum in Madrid, indicates that it was originally intended as the title page to the series. In the published edition, this print became plate 43, the number we can see in the top right corner” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, s.d.).

9Examples of some Brazilian productions: Arlindo (2021), by artist Luiza de Souza (Ilustralu); Quadrinhos Queer (2021), curated by Ellie Irineu, Gabriela Borges and Guilherme Smee; Sob a Luz do Arco-Íris (2020), curated by Mário César Oliveira; Revista Mina de HQ (https://www.minadehq.com.br), an annual publication, curated by Gabriela Borges.

Received: April 01, 2023; Accepted: June 12, 2023

texto em

texto em