Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista Lusófona de Estudos Culturais (RLEC)/Lusophone Journal of Cultural Studies (LJCS)

Print version ISSN 2184-0458On-line version ISSN 2183-0886

RLEC/LJCS vol.10 no.2 Braga Dec. 2023 Epub Feb 28, 2024

https://doi.org/10.21814/rlec.4691

Articles

Women, Politics and Graphic Humor in the Press of the Early 20th Century: A Brief Look at the Brazilian Case

iPrograma de Pós-Graduação em História Social, Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

This article addresses the representation and presence of women in the graphic humor of the Brazilian press in the early 20th century. We take three distinct examples as the main sources of the analysis: the caricatures of women made by the artist Nair de Teffé (under the pseudonym Rian) in the 1910s, the illustrations the Federação Brasileira pelo Progresso Feminino (Brazilian Federation for Women's Progress) used in the publications of the “Feminismo” (Feminism) section of the newspaper O Paiz in the late 1920s and, finally, the comic strips “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda” (Malakabeça, Fanika and Kabelluda) by Patrícia Galvão (popularly known as Pagu), published in the periodical O Homem do Povo in 1931. In addition to analyzing the works of these women, the article proposes a comparison with the comics published in the magazine O Malho, a mass humor periodical from the early 20th century. The highlighted illustrations, authored by the caricaturists J. Carlos and Leônidas, are representative of the dominant production of the time, which evoked sexist conceptions of gender relations. Our goal is to discuss the particularities and similarities of the works envisioned by women, in which the critical and subversive gaze of these figures predominated in the face of the society of their time. The historical and comparative approach makes it possible to recover these little-known graphic narratives, and shed light on the gender and power relations that constitute the universe of the press and humorous publications then.

Keywords: graphic humor; press; women; politics; feminism

O artigo visa refletir sobre a representação e a presença de mulheres no humor gráfico da imprensa brasileira no início do século XX. Tomaremos como fontes principais da análise três exemplos distintos: as caricaturas de mulheres feitas pela artista Nair de Teffé (com o pseudônimo Rian) na década de 1910, as ilustrações que a Federação Brasileira pelo Progresso Feminino utilizou nas publicações da seção “Feminismo” do jornal O Paiz no final da década de 1920 e, por fim, as tirinhas cômicas “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda” de Patrícia Galvão (popularmente conhecida como Pagu), publicadas no periódico O Homem do Povo em 1931. Além de analisar as obras dessas mulheres, o artigo propõe uma comparação com os quadrinhos publicados pela revista O Malho, um periódico humorístico massivo do início do século XX. As ilustrações destacadas, de autoria dos caricaturistas J. Carlos e Leônidas, são representativas da produção hegemônica da época, que evocava concepções sexistas das relações de gênero. Nosso objetivo é discutir as particularidades e as similaridades das obras idealizadas pelas mulheres, em que predominaram o olhar crítico e subversivo dessas figuras diante da sociedade de seu tempo. A abordagem histórica e comparativa possibilitará recuperar essas narrativas gráficas pouco conhecidas, bem como lançar luz às relações de gênero e de poder que constituem o universo da imprensa e das publicações humorísticas do período.

Palavras-chave: humor gráfico; imprensa; mulheres; política; feminismo

1. Introduction

The representation of women in the visual culture is not a recent theme of academic studies, but it continues to provide relevant and interesting works. A deeper look into feminist theories is central to these new productions, which bring forward renewed critical aspects and a closer look at gender relations. Studying women as producers of artistic works is hardly a recent effort. In 1971, the American historian Linda Nochlin discussed these and other questions in her essay that would become a classic: Por que Não Houve Grandes Mulheres Artistas? (Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?; Nochlin, 1971/2016). Getting into this subject brings with it some challenges of its own: how can we recover the creations of artists erased from history? Where do we find those sources? What more detailed information can be discovered about these women? If, on the one hand, some artists have been consecrated and recognized, on the other hand, there are dozens who remain anonymous and ignored.

Such questions also underpin the paths of research in the area of women’s history. The historian Michelle Perrot (2006/2016), a world reference in this field of studies, emphasizes the need to recover the accounts of the women themselves, breaking with the invisibility of their trajectories and with the silence of the sources. This intellectual effort to give voice to the women and their stories is part of a long process of institutionalization that began in the mid-20th century and was characterized by a continuous critical renewal. This is how the concept of gender as an analytical category (Scott, 1995) and the relational approach gain a place, bringing important issues to the debate, such as the tensions and negotiations between women and men, sexualities, notions of masculinities, and virility, among others. It is worth mentioning that, from the historiographical point of view, gender studies and women’s history are generally presented with orientations linked more to social history - aiming to recover the experiences of women of the past - and trends that favor the analysis of representations and discourses (Franco, 2015).

With regard to the issue of humor, there are several other particularities that appear on the scene. It is worth remembering that the very history of studies on the subject is permeated by difficulties in their being considered a field of research, largely because of the lack of prestige and academic indifference that lasted for decades (Saliba, 2017, p. 3). When we think of the historical context of Brazil in the early 20th century, there are also tensions regarding the humorists of the time and their self-images. Their trajectories were not always “uniform” or socially recognized, since society assigned the place of the humorist to the ephemeral, distant from the institutionalized circuits of culture and the Brazilian intelligentsia of that time (Saliba, 2002, p. 150).

In addition, bringing out the perspective of women’s history and gender relations implies adding new problems to the universe of humor: who are the women who produce humorous representations? What are the graphic characteristics of these works? How did they enter the professional environment? What relationships do their creations establish with feminist ideals? There are important reference studies to think about these issues in the Brazilian case. We highlight the doctoral thesis of Cintia Lima Crescêncio (2016), Quem Ri por Último, Ri Melhor: Humor Gráfico Feminista (Cone Sul, 1975-1988)

(The One Who Laughs Last, Laughs Best: Feminist Graphic Humor [Cone Sul, 1975- 1988]), as well as the works of Maria da Conceição Francisca Pires (2019, 2021a, 2021b), which focused on debating graphic humor in comics produced by women, the self-definition in comic books by black women, and transsexuality in comics. There is also the thesis De Maria a Madalena: Representações Femininas nas Histórias em Quadrinhos (From Mary to Magdalene: Female Representations in Comic Books) by Ediliane Boff (2014) and the dissertation Um Panorama da Produção Feminina de Quadrinhos Publicados na Internet no Brasil (A Panorama of the Female Production of Comics Published on the Internet in Brazil) by Carolina Ito Messias (2018), among others1.

However, the literature review shows that the reflections that align the two perspectives - the historical period of the early 20th century and the graphic humor productions made and/or disseminated by women (especially feminists) - are much scarcer. Despite this, we cannot fail to mention that important studies were carried out on some Brazilian artists of that time, such as Nair de Teffé: Artista do Lápis e do Riso (Nair Teffé: Artist of the Pencil and Laughter; Campos, 2016), which deals with the trajectory of Rian (the pseudonym adopted by Nair de Teffé), and some published articles that reflect on the visual production of Patrícia Galvão2. In any case, the scarcity of works stems from a number of factors, both historical and historiographical. Historically speaking, there are few women humorists and graphic artists known at the time, which possibly stems from a restriction that was imposed on the publishing and sociability networks of these media, dominated by men. Still, one cannot help but point out that forgetting and erasing women in the history of art, comics and graphic humor as a whole is also linked to historiography itself, as it is an arbitrariness perpetuated by studies, illustrated dictionaries and catalogs that gave prominence only to male artists3. In the case of Brazil, there is also some evidence that the history of graphic humor present in several collections silenced a significant part of the production of women (Crescêncio, 2018, p. 71).

By distancing oneself from the specificities of graphic humor - but without losing sight of it - it is also possible to reflect on the presence of women in the visual culture of the early 20th century from the political and artistic manifestations of some suffragist groups. The main objective of these groups of women was to gain the right to vote, as they understood that direct political participation was essential for their emancipation4. The use of the image as a fundamental part of the militancy of these groups has been further studied in the cases of American and, in particular, British suffragism, as in Lisa Tickner’s (1988) classic The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907-14. Even so, it is possible - and necessary - to recover the trajectories of suffragettes from other countries and regions that also used imagery resources. In Brazil, the conquest of women’s suffrage dates from 1932 and was enshrined in the Constitution of 1934. For decades, the activism was spearheaded by figures such as journalist Josefina Álvares de Azevedo (1851-1913) and professor Leolinda Figueiredo Daltro (1859-1935). In the 1920s, however, the movement gained a lot of visibility with the tactical action of the Federação Brasileira pelo Progresso Feminino (Brazilian Federation for Women’s Progress; FBPF), led by biologist Bertha Maria Júlia Lutz (1894-1976). Little by little, the FBPF was able to disseminate its ideals in the mainstream press, until in 1927 it inaugurated the column “Feminismo” (Feminism) in the newspaper O Paiz, where they were able to publish texts linked to feminist militancy5. This column also included images, photographs, propagandistic maps, and cartoons (charges6), probably produced by the FBPF members themselves.

We therefore propose a brief reflection in this work that relates and connects the different artists and works mentioned above, taking into account their particularities, their different intentions, and political positions, without losing sight of their points of agreement and their common political and social environment: the period traditionally called by historiographers as the “First Republic”. By juxtaposing these creations with each other, we seek to emphasize the discussions arising from the studies of women’s history and gender relations, in order to clarify the subversions and limits present in each narrative. The main sources addressed in this reflection are the three segments of visual productions: (a) the caricatures (more specifically the portrait-charges) by Rian (Nair de Teffé), published in the magazine Fon-Fon! in 1910; (b) the images - ranging from maps to cartoons - that illustrate the column “Feminismo” of the periodical O Paiz; and (c) the satirical strips “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda” (Malakabeça, Fanika and Kabelluda) by Patrícia Galvão, published in 1931 in the newspaper O Homem do Povo. These works will be contrasted with the hegemonic male production, which dominated the circulation in the mass media, so that we can see the innovations-in graphic and narrative terms - that women’s works triggered7.

2. Gender Relations and Graphic Humor in Early 20th Century Brazil

Various authors, both men and women, agree on the difficulty of establishing an accurate story about the emergence of comic books. There are genealogies that point to the origin of comics (or their “aesthetic precursors”) in the cave paintings, in the images d’Épinal of 18th-century France, or in the cordel literature of 18th- and 19th-century Spain; but, beyond the disagreements, there is a consensus that comics were born in the late 19th century as a genre subordinate to the graphic medium, having its history associated with the press (Levín, 2015, pp. 44-45). Thus, when we analyze the early period of the 20th century, we find a convergence of different visual expressions in illustrated magazines: they reproduced photographs, prints, advertising images, caricatures, cartoons, and comics. Thus, by using the term “graphic humor” we are able to conduct a joint approach to these manifestations that are so closely aligned in the documentary corpus of the research. Historian Florencia Levín (2015) defines graphic humor as:

a particular type of social discourse that captures fragments of ideas, images and opinions that circulate in other spaces where social exchange takes place; it transforms them and puts them back into circulation through the mass media, thus feeding the production of what constitutes, at the same time, its own raw material: the flow of social representations. And it does so by interweaving these networks of collective representations under the imaginary scenes constructed by the humorists (whether these references are from reality or not). Because graphic humor necessarily conveys what we call “common sense. (p. 24)

From this definition, we can understand graphic humor as an aesthetic expression with very striking social implications: common sense circulates and reproduces itself in the mass media, the fragments of ideas and opinions take visual form, are transformed, but are still social representations. Adopting graphic humor in its various forms as a source of historical study allows us to seek, among its vestiges, marks of mentalities and sensitivities of the past that may or may not remain in the present. Gender relations and the idealizations and projections of “femininity” and “masculinity” are always present if they are observed analytically, both by the representation present in the images, as well as in their own authorship and conception.

The data from the press and the bibliography on the subject reveal to us, however, that the “game of representations” arising from graphic humor was not on equal footing in terms of gender: in this context, most of the main cartoonists of the mass humorous magazines were men, who very often produced narratives that gave preference to sexist8 humor in the different scenarios illustrated. On this point, before we move on to the graphic productions of women, it is worthwhile to briefly analyze some images that represent this most well-known and widespread current of graphic humor in the early 20th century. For this, we will briefly analyze two comics from the humorous illustrated magazine O Malho, published in Rio de Janeiro beginning in 1902 and which, within a few years, reached a wide circulation in Brazilian urban centers through a significant weekly circulation.

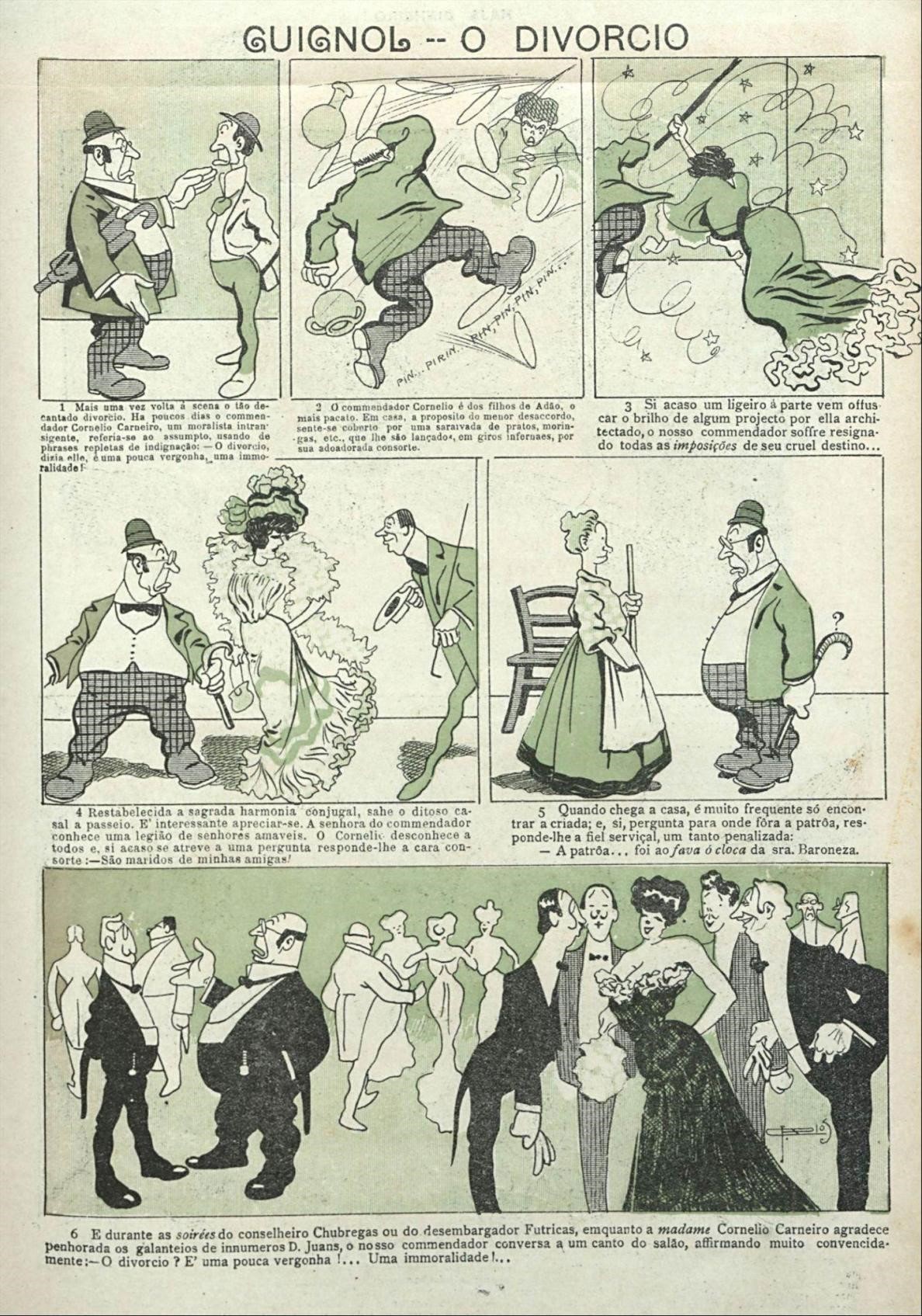

In various parts of the world, the laws regulating the right to divorce date back to the second half of the 20th century9. However, the debates on the subject go further back, as they had already been voiced by some feminists and were evidenced in the first attempts at bills that were presented in the early decades of the 20th century. In 1907, the topic was in vogue in Rio de Janeiro with the publication of the feuilleton “A Divorciada” (The Divorcée) in the magazine Kosmos (Guimarães & Ferreira, 2009), and it was a controversial subject at the meetings of the Institute of Lawyers, which the magazine O Malho said “approved by two-thirds” the “full divorce ( ... ) apparently, by Dr. Myrthes de Campos10” (Bocó, 1907, p. 8). This statement appears in the same issue in which the comic “O Divórcio” (The Divorce) is found, signed by the illustrator J. Carlos (Figure 1).

Source. From “Guignol - O Divórcio” [Illustration], by J. Carlos, August 17, 1907, O Malho, 257, p. 11. Available in the digital collection of the National Library. (http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/116300/9838)

Figure 1. “Once the sacred marital harmony had been re-established, the happy couple went for a walk. It’s interesting to watch. The commendatore’s mistress knows a legion of kind gentlemen. Cornelio doesn’t know them all and, if he dares to ask a question, his dear consort replies: - They’re the husbands of my friends!”

The graphic narrative focuses on the mishaps of the protagonist “Comendador Cornelio Carneiro, an intransigent moralist” (Carlos, 1907, p. 11) who was outraged by the possibility of recognizing the right to divorce. He is portrayed as a “naïve victim” of his own wife and the story outlines this idea by pointing out that, in the home, there were fights and discussions (represented in the first vignettes) and in the public space of social gatherings, the “embarrassment” of the “gallantries of countless D. Juans” - as shown by the outcome of the comic. Here we find a number of projections about femininity and masculinity, as well as sexist assumptions that govern humorous features of the narrative. The character that represents the wife of the protagonist has no name, is called “the commander’s lady”, “boss” and “madame Cornelio Carneiro”. She appears at the beginning of the story as an uncontrolled woman - which at the time was associated with the supposed feminine “emotional nature” - but as the story unfolds, she reveals her lascivious side, suggesting that she was having extramarital affairs. In addition, “the maid” is the other character who appears briefly in the story, portrayed in a stereotypical way as a naïve “faithful servant”. When communicating, she says “fava ó cloca” instead of five o’clock - a kind of parody of the foreign language used by many Brazilian comedians of the time to create comic effects11, but also, to point out the stupidity to those who uttered them.

In view of this, it is important to note that the comic, while following the style of the “comedies of manners”, imputes an extremely negative charge to the figure of the wife for the morality codes of the time. The protagonist of the narrative, in turn, rouses the reader’s amusement by his own stupidity, by not understanding the hypocrisy of his ideas in the face of his own marital relationship. Thus, the mockery is intrinsically associated with the sexist and patriarchal assumptions of the “husband’s authority”, which, by not being upheld in the case of Cornelio Carneiro, culminates in the ridicule of this character “betrayed by a woman” and “unable to control her”. Exploring this “crisis of male virility” as an antifeminist narrative12 was a recurring theme in the press and graphic humor, gaining even more emblematic contours in the context of the First World War (Moreira, 2021).

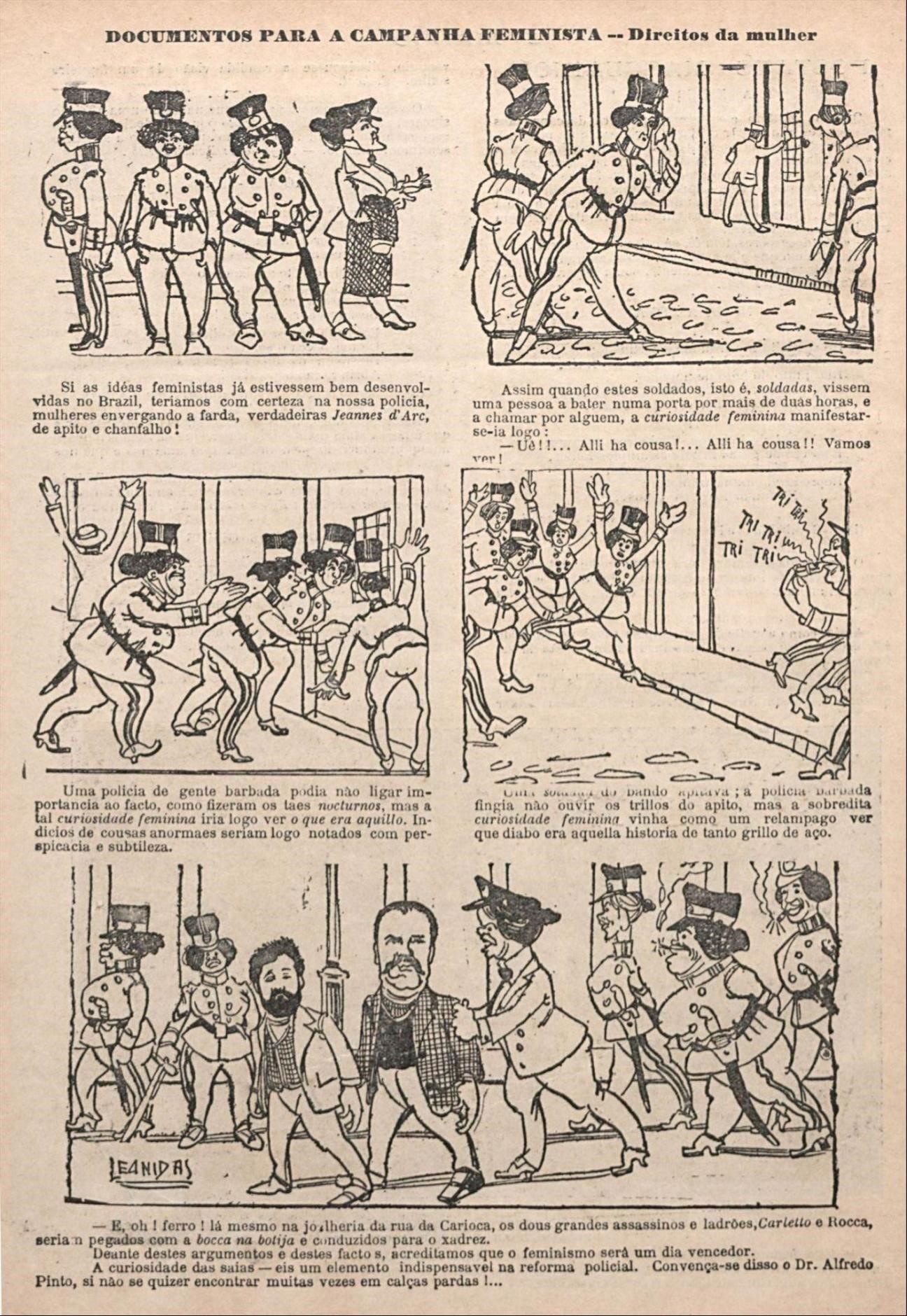

In 1906, in Rio de Janeiro, there was a crime that resonated in the press: the robbery of Jacob Fuocco’s jewelry store, which ended in murders and the criminals being nicknamed “death gang”. This episode inspired the comic strip by the cartoonist Leônidas (Figure 2), which narrates an alternate version of what happened, in which “the ideas of feminism were already developed in Brazil”, resulting in a squad of women police officers who would have put a different end to the story. Thus, we can assume that the idea of the author and the publisher of O Malho was to mobilize popular curiosity about what happened (it is no wonder there was a novel, a play and two films based on the crime) while dealing with an equally controversial subject at the time: feminism and the feminist campaign.

Source. From “Documentos Para a Campanha Feminista - Direitos da Mulher”[Illustration], by Leônidas, November 3, 1906, O Malho, 216, p. 42. Available in the digital collection of the National Library. (http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/116300/8272)

Figure 2. “If feminist ideas were already well developed in Brazil, we would certainly have women in our police force, real Jeannes d’Arc, with whistles and muzzles!”

Irony, essentialist conceptions of women, and the ridicule of feminists are the main axes of the graphic narrative. The positive outcome of the crime - with the arrest of the guilty caught in the act - justifies the title of the vignette, since the good outcome could be used as a “document for the feminist campaign” (Leônidas, 1906, p. 42). In addition, the good performance of women would be the result of “feminine curiosity”, a euphemism for the meddlesome behavior widely associated with women. If the title exhibits a certain mockery of feminist efforts13, the content (written and visual) of Leônidas' comic (1906) demonstrates, from a sexist point of view, that feminism would be responsible for the “distortion” of female figures. Although the “feminine behavior” of the characters was not out of line with common sense, the caricatured representation of them is designed to be absurd and shocking, because they wear uniforms (male clothing) and have their faces and bodies misshapen and grotesque, contrary to the aesthetic standards of the time. The mockery thus consists of the alternate outcome of the crime played by “masculinized women”- a stigma all too often associated with feminist women.

Briefly analyzing the two previous comics allow us to visualize the hegemonic scenario of graphic narratives in which representations of women and issues dear to feminism appeared. Large numbers of comics, caricatures and cartoons of similar content are found not only in the pages of O Malho - a widely disseminated publication in Rio de Janeiro - but also in other similar and equally popular publications. Women who appeared in comics as significant characters are often the targets of moralistic criticism and ridicule. Graphically, distortions are used when the intention is to delegitimize the figure of feminist women, distancing them from the idealized image of women that filled the advertisements of these same pages. Thinking about the presence of women in the production of graphic humor of the time therefore means taking into account the hostile environment evidenced by the masculine mass productions.

3. The Portrait-Charges by Rian

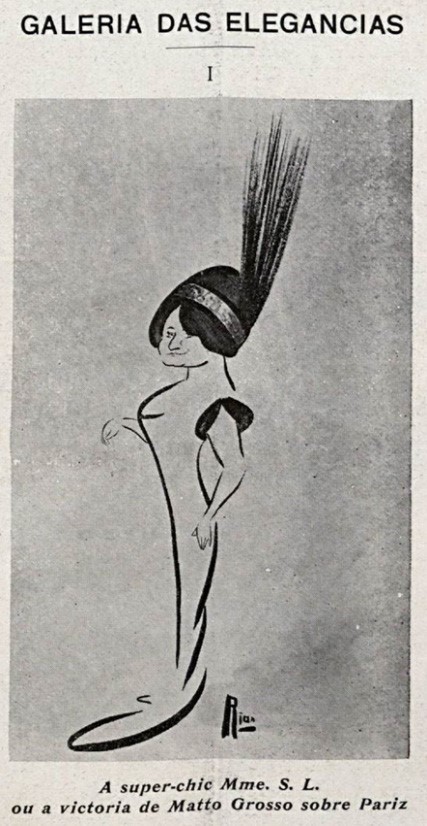

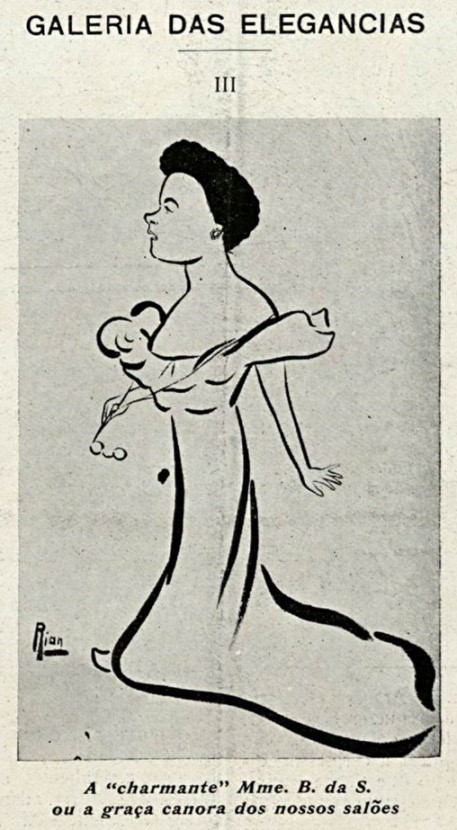

Nair de Teffé von Hoonholtz was born to an aristocratic family in the federal capital, Rio de Janeiro, in 1886. She is recognized as Brazil’s first female caricaturist, but above all she was a person who explored the art world in many ways, including experimenting with theater and music. In any case, Nair learned to draw during her stay in France and upon returning to Brazil she began her career as a visual artist in 1906, exhibiting weekly at Casa David and in the window of the millinery Chapelaria Watson (Campos, 2016). Beginning in 1910, Nair became known in the Brazilian mass media when she had a series of portrait-charges14 published in the illustrated magazine Fon-Fon!, in a session called “Galeria das Elegânicas” (Gallery of Elegances). By this time, she was already signing the illustrations as “Rian” (Nair backwards, which sounds like rien, “nothing” in French). The following are some illustrations (Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5).

Source. From “Galeria das Elegancias” [Illustration], by Rian, 1910a, Fon-Fon!, 33, p. 15. Available in the digital collection of the National Library. (http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/259063/4999)

Figure 3. “The super-chic Mme S. L., or the victory of Matto Grosso over Pariz”

Source. From “Galeria das Elegancias” [Illustration], by Rian, 1910b, Fon-Fon!, 34, p. 15. Available in the digital collection of the National Library. (http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/259063/5047)

Figure 4. “The 'pétillant' Mme S.S. or the evening star of select meetings”

Source. From “Galeria das Elegancias” [Illustration], by Rian, 1910c, Fon-Fon!, 35, p. 17. Available in the digital collection of the National Library. (http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/259063/5092)

Figure 5. “The 'charming' Mme B. da S. or the singing grace of our salons”

Graphically, we note the importance of the costumes and the fast strokes, which evidence exaggerations from synthetic figures. Rian’s caricatures evidence a certain critical mockery of the well-to-do women who frequented the social circles of the elites - of which she herself was a part (Boff, 2014, p. 221). On the other hand, there are certain subtleties in these depictions that are worth pointing out. The “ladies of Rian” gain a very different visibility than what was usually found in the graphic humor of the time, because there is no masculinization of their physiognomies or the suggestion that they were “morally deviant” women. They appear as protagonists of the visual narrative, with a name (albeit abbreviated) and the humor lies precisely in the authenticity of these figures, in their laughing expressions and in the exaggerated importance they attribute to fashion.

As Maria de Fátima Hanaque Campos (2016) well pointed out, Rian avoided the stereotypes of other caricaturists who represented women as biscuit or a sort of fragile adornments. In other words, when we compare the series with other hegemonic representations of women in the press, there are marked differences and a much less idealized view of femininity. Although she calls herself “nothing”, her images are nothing like naïve. Taking a new look at women and caricaturing even the male figures of the public scene and politics, as she would later do, are bold attitudes for a woman in that period. Although her social background granted her remarkable privileges, “modest” and “behaved” behavior was expected of women - especially bourgeois women, like her - and her works were a creative and subtle way of subverting gender projections that always fell on women too aggressively.

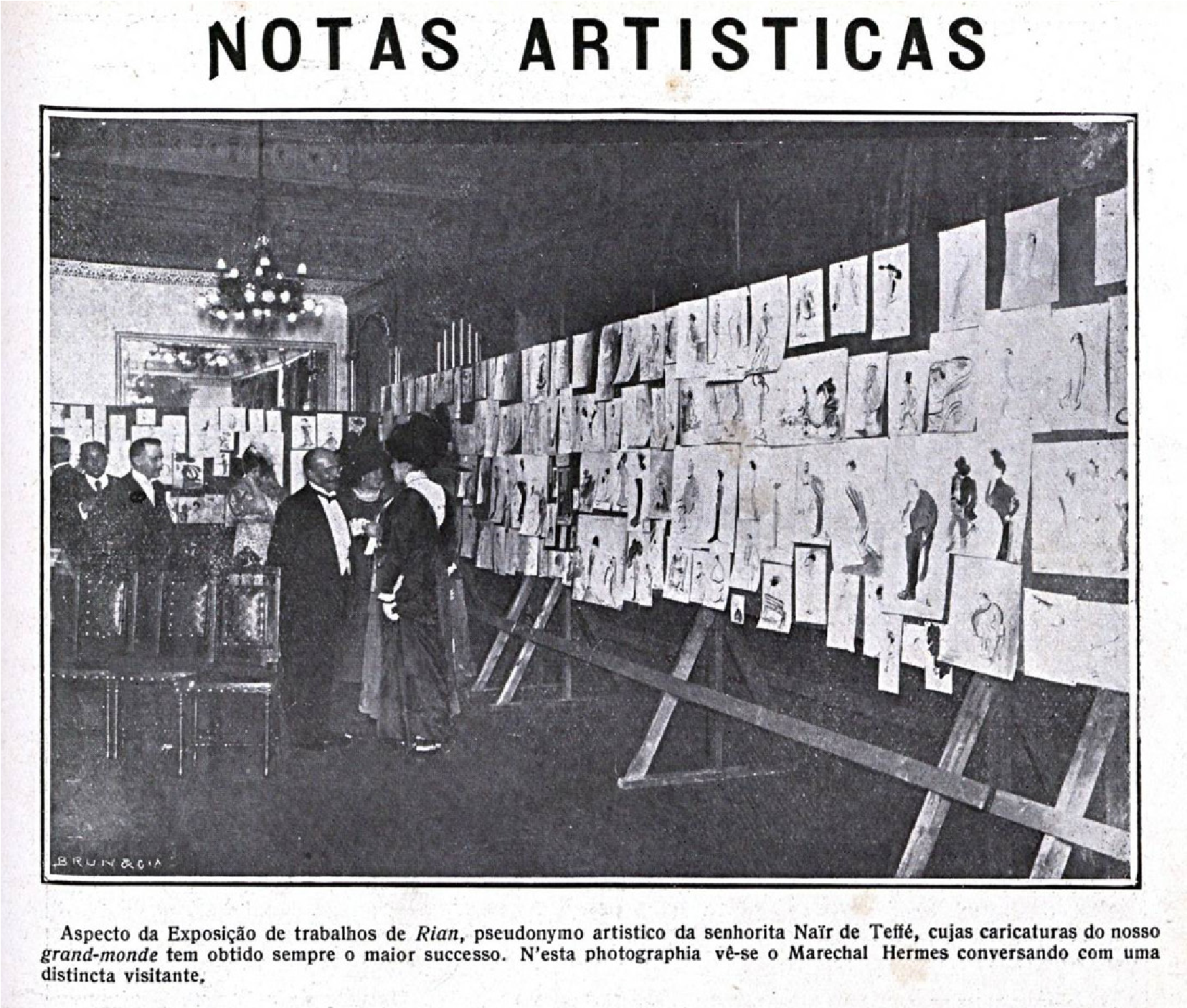

In fact, Nair experienced a moment of consecration between 1910 and 1912, receiving invitations for collaboration in the press, exhibiting her arts (Figure 6) and having her caricatures published not only in Fon-Fon!, but also in Careta and Gazeta de Notícias, equally important periodicals of Rio de Janeiro (Campos, 2016). In 1913 the artist married President Hermes da Fonseca and became the first lady of Brazil. The ceremony, as one might imagine, was a public event, reported and photographed by the newspapers and magazines of the time - including some negative comments by Fonseca’s opponents. According to Maria de Fátima Hanaque Campos (2016), the new marital status did not interfere with Rian’s career, but it was in the 1920s that the last caricature works of the artist are found in the illustrated press of Rio. In any case, it is worth noting that Nair de Teffé “lived between art and politics with the awareness that her modern and innovative artistic gestures had an extraordinary impact on a conservative and patriarchal political world” (Chagas, 2016, p. 62).

Source. From “Notas Artísticas” [Photography], by Brun&Cia, 1912, Fon-Fon!, 24, p. 23. Available in the digital collection of the National Library. (http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/259063/10297)

Figure 6. “A view of the Exhibition of works by Rian, the artistic pseudonym of Miss Nair de Teffé, whose caricatures of our grandmonde have always been a great success. This photograph shows Marshal Hermes chatting to a distinguished visitor”

4. Images at the Service of a Feminist Ideal - Federação Brasileira peloProgresso Feminino in O Paiz

Feminism and the ideals of “female emancipation” gained a lot of space in the press of the early 20th century, motivated above all by the intense political mobilizations of the suffragettes, both abroad and locally. A significant part of this repercussion was critical and derogatory, often through the publication of numerous anti-feminist caricatures, cartoons, and comics, which sought to ridicule and delegitimize the cause. This mass production of opposing images leads to the consideration that, for feminist militants, producing their own materials, whether texts or images, was a fundamental and necessary effort not only to garner public acceptance, but also to contend for their reputation, which was under constant attack by many widely circulated publications. In the specific case of English suffragism, especially that linked to the association Women’s Social and Political Union, historian Lisa Tickner (1988) demonstrated the vast arsenal of images mobilized by the militants, ranging from costumes for demonstrations, banners, accessories, photographs, propaganda postcards and periodicals of their own.

In the case of Brazil, the suffrage movement at the beginning of the century did not focus on organizing public demonstrations as recurrent and flashy as those of the English and American suffragism. Professor and feminist activist Leolinda Figueiredo Daltro, founder of the Partido Republicano Feminino (Women’s Republican Party) in 1910, even organized women’s marches and meetings in Rio de Janeiro, but there are no records suggesting that these acts were repeated very often or had many supporters. Beginning in 1922, the FBPF, led by the feminist biologist Bertha Lutz, began to prioritize, in turn, a performance focused more on conferences and political meetings. These events included the presence of guests (often foreigners) and were generally held in cafes or hotels, in other words, away from the streets and public squares. Instead of banners and posters, Brazilian feminists prioritized competing for space in the press for the public at large, as seen in the letter that Bertha Maria Júlia Lutz sent to the publisher of Revista da Semana, in 1918. According to Beatriz Berr Elias and Mônica Karawejczyk (2021, p. 14), periodicals, newspapers and magazines were one of the main tools for disseminating the acts of the FBPF, presenting its demands and arguments in favor of women’s vote as a way to expand its performance and increase its political alliances. It was especially in the newspaper O Paiz that the FBPF would find a privileged place to make its voice heard, in the column “Feminismo”, between the years 1927 and 1930.

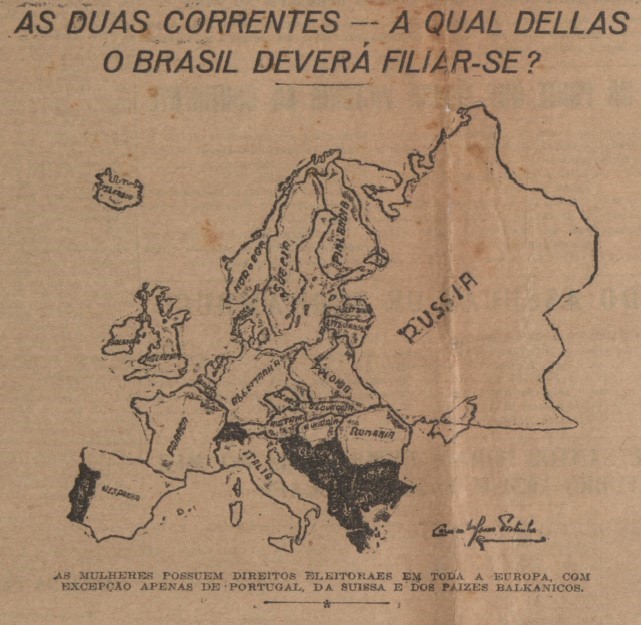

In their analysis of the column “Feminismo”, Beatriz Berr Elias and Mônica Karawejczyk (2021, p. 15) put forth the hypothesis that the periodical O Paiz began to cede this space to the FBPR because of the renewed interest in women’s political rights resulting from the approval of the female vote in the state of Rio Grande do Norte, in October 1927, seen as an expressive feminist victory of the time. The first times the section was published there were images next to the content, as we observed bellow, with the publication of a map entitled “As Duas Correntes - A Qual Dellas o Brasil Deverá Filiar-se?” (The Two Currents - Which Should Brazil Join?”; Figure 7). The image has a strong propaganda bias, as it alleges mass support for feminism in Europe (illustrated by the countries that were not colored on the map) to convince Brazilian readers that it is a legitimate cause that deserves their attention. It is interesting to note that the same illustration was reproduced on April 20, 1930, in the Diário Carioca, under the title “Federação Brasileira pelo Progresso Feminino” - however, this time, with the corrected list of countries that admitted the female vote in Europe, since, in 1927, the map considered France as part of this “suffragist current”, but in reality the country only regulated these political rights for women in 1945.

Source. From “As duas correntes- A qual dellas o Brasil deverá afiliar-se?” [Illustration], by Carmen Velasco Portinho, November 11, 1927, O Paiz,15727, p. 7. Available in the digital collection of the National Library. (http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/178691_05/31913)

Figure 7. “Women have voting rights throughout Europe, with the exception of Portugal, Switzerland and the Balkan countries”

Although this image is not the focus of our analysis, we call attention to the use of maps as a way to communicate ideas. There are sources that attest to how the suffragettes of the United States, as early as the 1910s, wielded this type of visual representation to defend their demands. Similarly, in the following decades there are other

“suffragist maps” in political materials of the militants of South America, such as the one we reproduced earlier and a map drawn up in 1929 by the Uruguayan feminist Paulina Luisi, who pointed out in her caption: “80 million women vote in the world - Uruguayan women have no rights”. It is worth noting that these women are using maps as propaganda at a time when such representations were very closely associated with the “world of men”, the expansionist/colonialist policies of some countries and the war tensions that exploded from the end of the 19th century until the First World War. They are thus appropriating these symbols to remark on the transnational and deeply political nature of women’s suffrage.

In 1929 the FBPF decided to publish in its column the article “Resistindo à Invasão Feminista” (Resisting the Feminist Invasion), also counting on the cartoon reproduced in Figure 8. The context of the publication is a controversy involving a Post Office report that opposed the admission of women in the postal service, claiming that women were “auxiliaries who did not offer advantages to the smooth running of bureaucratic work”, since their efforts were always “inattentive and flawed” (“Resistindo à Invasão Feminista”, 1929, p. 10). The FBPF reacted to the event, noting that the report “overflowed with antifeminist prejudice”, that the director and author of the document “appeared to belong to a philosophical school of the past” (“Resistindo à Invasão Feminista”, 1929, p. 10) and that it violated a constitutional right of Brazilian women. The cartoon, in line with the criticism of the report’s statements, makes use of graphic humor to ridicule such anti-feminist men who remained resistant to female participation in certain areas and concludes: “in the 20th century, the broom of prejudice does not frighten women”. This mention of the 20th century can be understood as a tactic, recurrently employed by suffragettes, of associating feminism and women’s rights with the most modern practices of their time. In other words, “to be in the 20th century” is “to be in the time of the criticism of old habits”, so that resistance to changes in the condition of women in society appears as an appeal to the, archaic, past. Such an argument was highly likely to be forceful among readers at a time when modernist ideas were gaining ground, permeated by the eagerness to build new airs and paradigms.

Source. From “Resistindo à invasão feminista” [Illustration], March 3, 1929, O Paiz, 16205, p. 10. Available in the digital collection of the National Library. (http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/178691_05/37515)

Figure 8. “'We need to raise a great levee against the devastating wave that is coming and that wants to swallow us up,' says the worthy judge, Dr Esaú de Moraes. However, H.E. forgets that: 'In the 20th century, the broom of prejudice does not frighten women'”

Concerning the graphics, the cartoon does not employ the usual approaches of antifeminist graphic humor, such as the use of grotesque features, absurdities or exaggerations in the physiognomies and bodies of the characters. The scene acquires a humorous and critical tone only by the analogy that is made with the “broom of prejudice”, wielded by the male character doubly ridiculed, both by the cartoon itself and by the women represented within the scene - laughing at the subject who tries in vain to “raise a big levee”. We can point out as a hypothesis that the relatively mild nature of the image stems from a conscious attempt to move away aesthetically from antifeminist cartoons, in addition to preserving a “polished” image of feminist criticisms. In other words, not resorting to the emotionally charged representations recurrent in the graphic humor of many antifeminist men may have been a convenient way of not linking themselves to a practice “as masculine” as were the political satires, since these militants lived under the continuous public accusation that they were “masculinized” for claiming political rights.

5. The Strips of Pagu

Patrícia Rehder Galvão was born in São João da Boa Vista, in the interior of the state of São Paulo, in 1910. Pagu, as she became known, led an intense life, continually breaking with many social standards and traditional expectations of “female behavior”.

She is publicly remembered as a communist militant and writer, but she also had a number of works linked to the visual arts that are not always mentioned. Pagu began to draw in the magazine Antropofagia, presenting an album of drawings and texts dedicated to the painter Tarsila do Amaral (Boff, 2014, p. 222). In addition, she produced sketches that were collected and published only in 2004 in the book Croquis de Pagu: E Outros Momentos Felizes que Foram Devorados Reunidos (Pagu’s Sketches: And Other Happy Moments That Were Devoured Collected), organized by Lúcia Maria Teixeira Furlani (2004). For our analysis, we selected the strips “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabeluda” prepared for the weekly O Homem do Povo, edited in São Paulo in 1931 by her and Oswald de Andrade - her husband at the time.

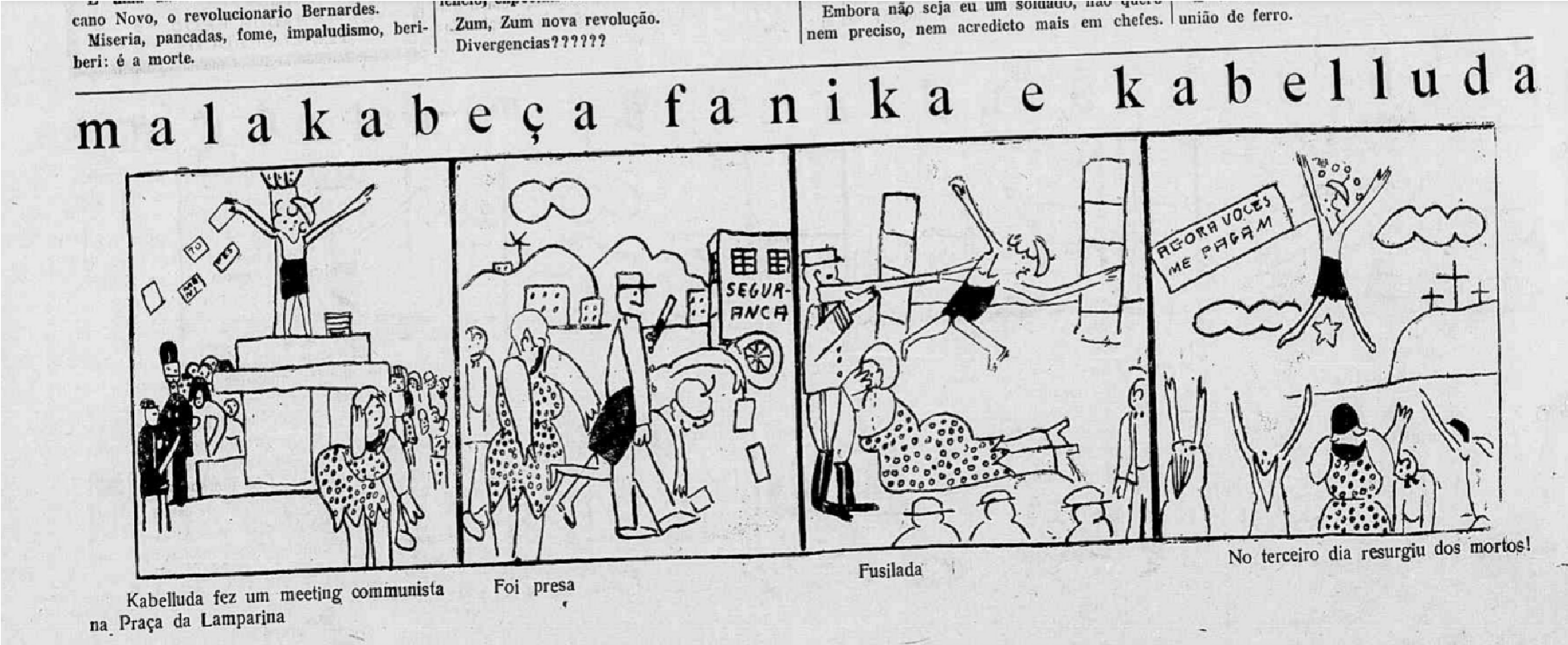

The first point to highlight is that Patrícia Galvão’s comics, like her novels and other writings, evidenced parts of the author’s own experience and can be considered as autobiographical productions (Nogueira, 2017, p. 5). Kabelluda is the protagonist of her strips in O Homem do Povo and possibly has many things in common with Pagu herself, because the character is combative, participates in political actions and lives her sex life freely, which was considered a scandal by the moral standards of the time. In Issue 4, the narrative illustrates the protagonist’s participation in a communist meeting in a public space, called “Praça da Lamparina” (Lamparina Square; Figure 9). She is immediately surprised by the police repression, expressed in a light and crude way, as Kabelluda “is arrested” and then “shot” (Galvão, 1931a). There is a rapid breakdown of expectation between the woman who vibrates, at the head of a demonstration, and her total opposite, when she is stopped and silenced. However, the expectation is again distorted with the reappearance of the character in the last frame - which, in turn, is a clear satirical allusion to the biblical passage that narrates the resurrection of Christ. Kabelluda’s reappearance is celebrated by other characters who were already on the scene, among them, some women.

Source. From “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda”, by Patrícia Galvão, April 2, 1931a, O Homem do Povo, 4, p. 6. Available in the digital collection of the National Library. (http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/720623/24)

Figure 9. “Kabelluda held a communist meeting in Praça da Lamparina”

Although it may seem a simple and rudimentary story to our eyes today, Pagu addresses a controversial topic for the 1930s: the participation of women in politics through militancy. The personalities who chose this path, regardless of their ideological bias, encountered strong opposition within and outside the movements. In addition, they faced harsh criticism from public opinion and some even suffered political persecution, as was the case with Patrícia Galvão. Kabelluda was brutalized and imprisoned, anticipating what the future of her own creator would be (Nogueira, 2017, p. 8). In addition, we can highlight how Pagu uses various comic elements with an acidity of her own, bearing in herself a message of self-affirmation of the woman who defends her political ideals: Kabelluda, on resurfacing, was external to the world: “now you pay me!”.

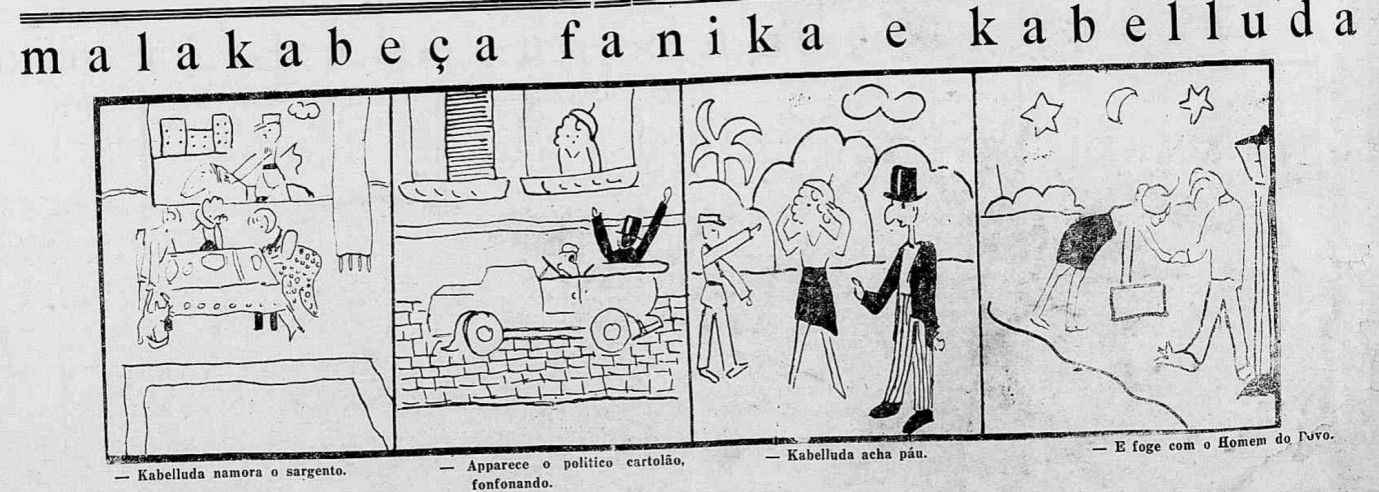

In turn, the vignette published in Issue 7 addresses a dimension of the character’s free sexuality, because she becomes involved with several men and in the end chooses, according to her own will (and without constraints), which one she wants to escape with - “the man of the people” himself (Galvão, 1931b; Figure 10), from which the newspaper takes its name. Kabelluda rejects “the sergeant” and “the politician in the top hat”, which also demonstrates her rebelliousness and her criticism of the bourgeois ideals of marriage, demonstrating that these figures, even if they had social prestige in the eyes of society, were of little interest to her. In graphical terms, the light and fun strokes are maintained, humorously contrasting the playful scenarios - clouds and stars - with the revolutionary and bold female protagonist.

Source. From “Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda” [Illustration], by Patrícia Galvão, April 9, 1931b, O Homem do Povo, 7, p. 6. Available in the digital collection of the National Library. (http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/720623/42)

Figure 10 “Kabelluda flirts with the sergeant. The card-carrying politician appears, phoning. Kabelluda thinks he’s a páu. And runs off with the Man of the People [Homem do Povo]”

If we compare it to the comic “O Divórcio" (The Divorce), analyzed earlier herein, there is a significant change in the way this character is seen in the face of her own sexuality. The woman is not portrayed from a conservative and sexist morality. Kabelluda owes no explanations to the men she abandons and is not judged by the narrative, as in the case of “Madame Cornelio Carneiro”. In Pagu’s other strips, the gender dimensions are equally present: she addresses the theme of unrecognized motherhood (and the public repudiation generated by it), female rivalry and the reproduction of sexism by women themselves, as well as the issue of rebellion and political subversion when driven by a woman.

6. Women Who Illustrate, Who Make People Laugh, Who Do Politics

In the first three decades of the 20th century Brazil went through intense political transformations, ranging from the consecration to the withering away of the so-called “First Republic”. This is the common context of these different groups of sources that we have mentioned so far, which demonstrate, in a way, how the perspectives of changes in the relations between men and women were also part of this scenario of quarrels and tensions. In this context, observing the plurality of representations present in women’s graphic production, in particular, allows us to consider how greatly these initiatives, among other things, sought to break with the current sexist conceptions. Thus, what is evident in all their works, be they comics, cartoons, or caricatures, is the yearning (and daring) of women who assume the voice of narration about themselves, placing themselves as women producers and women who communicated to other women.

Whether to give visibility to their compatriots in the salons, to criticize and laugh at anti-feminist men or to make the hypocrisies and elitism of bourgeois society abundantly clear, what they all have in common is the gesture of taking away the authority of men to make discourses about them, about their rights and about their behaviors. It is always worth remembering that this masculine authority was enshrined in patriarchal laws still in force at that time - such as the Civil Code and the Constitution itself, which, for example, did not provide for the vote of women.

In the creations of Rian, FBPF and Pagu, there are also changes in the patterns of the current graphic humor (generally, as we have seen, of sexist and/or anti-feminist content). This time it is men who are the targets of laughter and mockery - not because they are men, but because they are irrelevant and old-fashioned for the purposes of the female characters. There is also the presence of female laughter, portrayed as a natural gesture of women, and not some kind of moral innuendo about their own behaviors. As Cintia Lima Crescêncio (2016) highlighted, we can draw attention to the difference in the humorous approach of feminist bias, which starts from assumptions and themes distinct from those of hegemonic and antifeminist humor. The author even demonstrates that, between the activists of the 1970s and 1980s, the theme of feminism itself was uncommon in her productions (Crescêncio, 2017, p. 88), which is symptomatic, because it is at odds with the mass antifeminist humor that usually did not miss any chance to make jokes about the social movement and its representatives. The works of women that we analyzed earlier, on the contrary, feature figures permeated by the desire for self-determination - which is, after all, a pillar of feminism, even if some of these illustrations were not produced with this explicit bias.

Thus, briefly observing the trajectory of comics and graphic humor from a perspective that privileges gender as a category of analysis shows us that, despite the scenario of disputes, the feminist perspective of valuing the subjectivity of women is imposed from a very early age in the productions they made and/or disseminate. In this sense, it is not a question of reaffirming an essentialist point of view about women artists and their works. The question posed is that Rian, the columnists of FBPF and Patrícia Galvão evidenced, through different forms and approaches, that the graphic medium could also be a means for expressing counterpoints and criticisms to the sexist trends of female representation. Female characters did not always have to be the butt of the joke “for being women” or for “behaving like women”. They could be the protagonists of the stories; they could laugh at the other figures on the scene; they could deal with political matters - all without going through the cynical moral judgment of ironic humor or grotesque traits they aimed to ridicule. In this sense, they are innovative works from the point of view of gender.

The relationship between women, politics, and visual representations by comics is not a connection that is restricted to the past. On the contrary, the subversion expressed in the illustrations of the early 20th century is still reflected in the most current works that deal with the same themes. An example of this is the graphic novel Bertha Lutz e a Carta da ONU (Bertha Lutz and the UN Charter; Amma & Kalil, 2021), published by Veneta in 2021.

The comic tells the story of Bertha Lutz’s stint as a representative of the 1945 “San Francisco Conference”, where the United Nations Charter was drafted, which aimed to create a postwar global pact of peace and international cooperation. In this important episode of international politics, the Brazilian feminist played a central role in incorporating gender equality into the official document. According to the authors of the comic, Amma and Angélica Kalil, the account very faithfully follows the Reminiscências da Confederação de São Francisco (Reminiscences of the Confederation of San Francisco) that Bertha had written in the 1970s, and the project ensured that “the narrative would remain in Bertha’s hands, she herself would be in control” (Amma & Kalil, 2021, p. 120).

The challenge of bringing the feminist perspective to the representations remains perennial, linking the past and the present, because women with the political importance of Bertha Lutz remain unknown to the general public. Contemporary productions such as Bertha Lutz e a Carta da ONU (Amma & Kalil, 2021, p. 120) therefore continue the exercise of women artists and writers to re-signify their own images, especially when it comes to the world of politics. After all, the pejorative stereotypes of women in politics and feminists are numerous, still marked by misogynistic images and associations that, until now, have stood the test of time.

7. Final Considerations

Studying women in comics and graphic humor, whether as authors or as representations, is not just a gesture of recognition. Incorporating them into the analyses is a fundamental step in understanding more fully the whole universe of these visual expressions: after all, women have always appeared in the narratives and have always been part of the societies in which those representations were created. Highlighting the feature of gender relations is a theoretical option not to make invisible the extent to which those power conflicts permeate the different groups that produce and consume material culture at different times. One purpose of this brief look at the Brazilian case was to go beyond the historical retrospect of women cartoonists of the early 20th century. Through the contrast with the hegemonic sexist productions, we were interested in highlighting how gender issues and female self-image are transformed in the works idealized by Nair de Teffé, by the FBPF militants who worked on the column “Feminismo” and by Patrícia Galvão, Pagu.

Despite the persistent sexism, by the beginning of the 20th century there were differentiated and protesting representations produced by women. In their features, we see new ways of portraying characters in the comics, understanding these figures as subjects of their own history and their own wills, without becoming targets of ridicule. These women laugh at men, but they also laugh at themselves. They demonstrate, through images, the importance of continuously building their place in politics and the public sphere and of defending their ideals with the widest range of strategies. Although their works may have fallen into oblivion or marginality, they made contributions to graphic humor itself, since their perspectives on female representation put stress on the flow of ideas, images, and opinions current in the press. With this, they began to occupy spaces historically denied to them, leading the public discussion on political issues, behaviors, and the female condition. As summarized by Carolina Ito Messias (2018) at the conclusion of her master’s degree:

the world of comic books has always featured talented women, since the early days of the printed press. Bringing women’s production to light means recognizing the agency of women as creators and enriching the public debate with other narratives and looks at reality, other ways of approaching (and, above all, questioning) what it is to be a woman. (p. 99)

Acknowledgements

This article is the result of research funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, process number 2020/05001-9.

REFERENCES

Amma, & Kalil, A. (2021). Bertha Lutz e a Carta da ONU. Editora Veneta. [ Links ]

Barros, J. C. (2020). Mulheres quadrinistas: No Ceará tem disso, sim! Editora Appris. [ Links ]

Bergmann, M.(1986). How many feminists does it take to make a joke? Sexist humor and what’s wrong with it. Hypatia, 1(1), 63-82. [ Links ]

Bocó, J. (1907, 17 de agosto). Chronica. O Malho, 257, 8. http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/DocReader. aspx?bib=116300&pagfis=9835 [ Links ]

Boff, E. D. O. (2014). De Maria a Madalena: Representações femininas nas histórias em quadrinhos [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade de São Paulo]. Biblioteca Digital. https://doi.org/10.11606/T.27.2014. tde-20052014-123753 [ Links ]

Brun&Cia. (1912, 15 de junho). Notas artísticas [Fotografia]. Fon-Fon!, 24, 23. http://memoria.bn.br/ docreader/259063/10297 [ Links ]

Campos, M. D. F. H. (2016). Nair de Teffé: Artista do lápis e do riso. Appris Editora e Livraria Eireli-ME. [ Links ]

Carlos, J. (1907, 17 de agosto). Guignol - O divórcio [Ilustração]. O Malho, 257, 11. http://memoria.bn.br/ docreader/116300/9838 [ Links ]

Chagas, M. (2016). Nair de Teffé: Uma mulher entre a arte e a política. In M. E. A. D. Assis & T. V. D. Santos (Eds.), Memória feminina: Mulheres na história, história de mulheres (pp. 58-67). Editora Massangana; Fundação Joaquim Nabuco. [ Links ]

Crescêncio, C. L. (2016). Quem ri por último, ri melhor: Humor gráfico feminista (Cone Sul, 1975-1988) [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina]. Repositório Institucional. https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle/123456789/168070 [ Links ]

Crescêncio, C. L. (2017). “Tá rindo de quê?” ou os limites da teoria humor gráfico na imprensa feminista do Cone Sul. Revista Territórios e Fronteiras, 10(2), 75-92. https://doi.org/10.22228/rt-f.v10i2.734 [ Links ]

Crescêncio, C. L. (2018). As mulheres ou os silêncios do humor: Uma análise da presença de mulheres no humor gráfico brasileiro (1968-2011). Revista Ártemis, 26(1), 53-75. https://doi.org/10.22478/ufpb.1807-8214.2018v26n1.42094 [ Links ]

Elias, B. B., & Karawejczyk, M. (2021). “Sempre à mulher, pela mulher”: A coluna Feminismo no jornal O Paiz (RJ) - 1927-1930. História em Revista, 26(2), 10-26. https://doi.org/10.15210/hr.v26i2.21572 [ Links ]

Eugênio, J. D. (2017). Elas fazem HQ!: Mulheres brasileiras no campo das histórias em quadrinhos independentes [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina]. Repositório Institucional. https://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle/123456789/183629 [ Links ]

Ferrara, J. A. (2019). Modernidade e emancipação feminina nas tirinhas de Pagu. Darandina Revisteletrônica, 10(2) 1-20. https://doi.org/10.34019/1983-8379.2017.v10.28132 [ Links ]

Franco, S. M. S. (2015). Gênero em debate: Problemas metodológicos e perspectivas historiográficas. In M. Villaça & M. L. C. Prado (Eds.), História das Américas: Fontes e abordagens historiográficas (pp. 36-51). Humanitas. [ Links ]

Furlani, L. M. T. (Ed.). (2004). Croquis de Pagu: E outros momentos felizes que foram devorados reunidos. Cortez; Unisanta. [ Links ]

Galvão, P. (1931a, 2 de abril). Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda [Ilustração]. O Homem do Povo, 4, p. 6. http:// memoria.bn.br/DocReader/720623/24 [ Links ]

Galvão, P. (1931b, 9 de abril). Malakabeça, Fanika e Kabelluda [Ilustração]. O Homem do Povo, 7, p. 6. http:// memoria.bn.br/DocReader/720623/42 [ Links ]

Guimarães, L. M. P., & Ferreira, T. M. T. B. da C. (2009). Myrthes Gomes de Campos (1875-?): Pioneirismo na luta pelo exercício da advocacia e defesa da emancipação feminina. Revista Gênero, 9(2), 135-151. https://doi.org/10.22409/rg.v9i2.85 [ Links ]

Kohn, J. (2016). Women comics authors in France and Belgium before the 1970s: Making them invisible. Revue de recherche en civilisation américaine, (6). [ Links ]

Leônidas. (1906, 3 de novembro). Documentos para a campanha feminista - Direitos da mulher [Ilustração], O Malho, 216, 42. http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/116300/8272 [ Links ]

Levín, F. P. (2015). Humor gráfico: Manual de uso para la historia. Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento. [ Links ]

Messias, C. I. (2018). Um panorama da produção feminina de quadrinhos publicados na internet no Brasil [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade de São Paulo]. Biblioteca Digital. https://doi.org/10.11606/D.27.2019.tde-22022019-150556 [ Links ]

Moreira, T. B. R. (2021). O (anti)feminismo nas representações da virilidade na imprensa ilustrada humorística (Brasil e Argentina, 1904-1918). Revista Eletrônica da ANPHLAC, 21(31), 257-292. https://doi.org/10.46752/anphlac.31.2021.3951 [ Links ]

Nochlin, L. (2016). Por que não houve grandes mulheres artistas? (J. Vacaro, Trad.). Edições Aurora. (Trabalho original publicado em 1971) [ Links ]

Nogueira, N. A. D. S. (2017, 24-28 de julho). Pagu: Política e pioneirismo nas histórias em quadrinhos nos anos de 1930 [Simpósio]. XXIX Simpósio Nacional de História. Contra os preconceitos: História e democracia, Brasília, Brasil. [ Links ]

Perrot, M. (2016). Minha história das mulheres (2.ª ed.; A. M. S. Côrrea, Trad.). Editora Contexto. (Trabalho original publicado em 2006) [ Links ]

Pires, M. da C. F. (2019). Outras mulheres, outras condutas: Feminismos e humor gráfico nos quadrinhos produzidos por mulheres. Artcultura: Revista de História, Cultura e Arte, 21(39), 71-87. https://doi.org/10.14393/artc-v21-n39-2019-52027 [ Links ]

Pires, M. da C. F. (2021a). Autodefinição e corpos negros emancipados nas HQs de Bennê Oliveira e Lila Cruz. Revista de la Red Intercátedras de Historia de América Latina Contemporánea, (15), 180-205. [ Links ]

Pires, M. da C. F. (2021b). Transexualidade em quadrinhos: Narrativa autobiográfica nas histórias de Sasha, a leoa de juba e Alice Pereira. Anos 90, 28, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.22456/1983-201X.110580 [ Links ]

Portinho, C. V. (1927, 11 de novembro). As duas correntes - A qual dellas o Brasil deverá afiliar-se? [Ilustração]. O Paiz, 15727, 7. http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/178691_05/31913 [ Links ]

Resistindo à invasão feminista [Ilustração]. (1929, 3 de março). O Paiz, 16205, 10. http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/178691_05/37515 [ Links ]

Rian. (1910a, 13 de agosto). Galeria das elegancias [Ilustração]. Fon-Fon!. 33, 15. http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/259063/4999 [ Links ]

Rian. (1910b, 20 de agosto). Galeria das elegancias [Ilustração]. Fon-Fon! 34, 15. http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/259063/5047 [ Links ]

Rian. (1910c, 27 de agosto). Galeria das elegancias [Ilustração]. Fon-Fon!, 35, 17. http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/259063/5092 [ Links ]

Saliba, E. T. (2002). Raízes do riso: A representação humorística na história brasileira da Belle Époque aos primeiros tempos do rádio: Da belle époque aos primeiros tempos do rádio. Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Saliba, E. T. (2017). História cultural do humor: Balanço provisório e perspectivas de pesquisas. Revista de História, (176), 1-39. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9141.rh.2017.127332 [ Links ]

Scott, J. W. (1995). Gênero: Uma categoria útil de análise histórica. Educação e Realidade, 20(2), 71-99. [ Links ]

Tickner, L. (1988). The spectacle of women: Imagery of the suffrage campaign 1907-14. University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

1Other references that we could cite are: Eugênio (2017), from the Center for Philosophy and Human Sciences, Graduate Program in Political Sociology, Florianópolis; Barros (2020).

2Among them: Nogueira (2017) and Ferrara (2019).

3Author Jessica Kohn (2016) demonstrates in her study how this forgetting was perpetrated by some illustrated dictionaries authors in the case of comic books in France and Belgium before 1970.

4New Zealand (1893), Australia (1902) and Finland (1906) were pioneering countries in women’s suffrage. In Brazil, the conquest occurred in 1932 and became effective in the Constitution of 1934, a few years after the United States (1920) and the United Kingdom (1928). In Portugal, women’s suffrage was realized in 1976, within the scope of political transformations after the Carnation Revolution.

5A full analysis of the column is made by Beatriz Berr Elias and Mônica Karawejczyk (2021) in an article entitled “’Always to the Woman, For the Woman’: The Feminism Column in the newspaper O Paiz (RJ) - 1927-1930”.

6The word “charge”, derived from the French, meaning “charge” or “attack”, refers to a form of humorous satire widely prevalent in satirical magazines of the time. It uses illustrations or drawings with short captions to comment on current political, social or cultural issues. Typically, cartoons employ comedic exaggeration of features and situations to deliver criticisms and impactful messages.

7It is important to emphasize that there is currently no robust survey of graphic humor productions made by women in Brazil in the early 20th century. The absence of data poses challenges for the field of study, which typically leans towards relying on the few names still known in the bibliography.

8Merrie Bergmann (1986) conceptualizes “sexist humor” as “one in which sexist beliefs, whether attitudes or norms, are presupposed and necessary for fun” (p. 63).

9Uruguay is an exception in the Latin American context. In October 1907, after heated parliamentary and public debates, the country enacted the law that would regulate divorce from then on.

10Myrthes Gomes de Campos (Macaé, 1875 - Rio de Janeiro, January 20, 1965) was a Brazilian lawyer, recognized as the first woman in Brazil to practice this profession. Myrthes was engaged in the cause of women’s emancipation, defended the right to vote for women and, in the 1920s, had close relations with the Federação Brasileira pelo Progresso Feminino.

11This kind of parody of foreign languages or exaggerated foreignisms is analyzed in more detail by Elias Thomé Saliba (2002) in Raízes do Riso - A Representação Humorística na História Brasileira: Da Belle Époque ao Primeiros Tempos do Rádio (Roots of Laughter - The Humorous Representation in Brazilian History: From Belle Époque to the Early Times of Radio).

12Such anti-feminist positions denied, in different ways, the legitimacy of claims for women’s political and civil rights. With regard to academic production, misogyny and antifeminist discourses have been studied from different interpretations, from those that point to a given “fear of women” and “fear of change” on the part of men, to those that analyze them as reactionary rhetoric or a manifestation of symbolic violence (Moreira, 2021, p. 264).

13Although in 1906 there were no feminist associations of greater projection in Brazil, as was the case a few years later, with the founding of the Partido Republicano Feminino (Women’s Republican Party; 1910) and the Liga para a Emancipação Intelectual da Mulher (League for the Intellectual Emancipation of Women; 1919), we cannot fail to point out that some activists for the emancipation of women were already known in Brazil, and had acted through written publications, such as Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta (1810-1885) and Josefina Álvares de Azevedo (1851-1905).

Received: March 31, 2023; Accepted: May 08, 2023

text in

text in