1. The Work of Professional Caregivers of Battered Women

Violence against women is a phenomenon characterized by the use of real or symbolic force by someone aiming to subject a woman’s body, mind, and will (Bandeira, 2014). It is a fact that deserves both attention and care of a professional care network in countries such as Brazil and Spain. This reality is the result of official movements and demarcations that have led to the creation of this network of services for these targets in the Brazilian and Spanish realities.

In Brazil, this reality became significant when the country signed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979). In order to fulfill the obligations outlined in this provision, Law No. 11.340 (Lei nº 11.340, 2006), also known as the “Maria da Penha Law”, was created in 2006. This legal framework lists forms of violence against women, integrated prevention measures, assistance to women in situations of intimate partner and family violence, and the actions to be taken by the police authority and protective measures. According to this legal framework, the forms of violence against women are physical violence, psychological violence, sexual violence, property violence, and moral violence (Lei nº 11.340, 2006).

The national policy to fight violence against women (Secretaria Nacional de Enfrentamento à Violência contra as Mulheres, 2011) was also developed as a means of qualifying the conceptual axes, principles, guidelines, and practices for institutional actors immersed in the fight against violence against women. This paper details the service network for the cases served. Among the services listed for this purpose are the Women’s Reference Centers, the Specialized Women’s Assistance Stations, and the Specialized Referral Center in Social Assistance.

In Spain, this type of service became available after the approval of the Organic Law on Protective Measures for Comprehensive Protection against Gender Violence in 2004 (Ley Orgánica 1/2004, 2004), in line with the United Nations recommendations. This legal instrument sets measures of sensitization, prevention, detection, and care for violence against women. The latter includes guaranteeing access to information and integrated social services through continuing and emergency care services by a multidisciplinary professional team. These services are offered through different means: telephone lines, emergency centers, shelters, associations, administrative, judicial, and police services, among others (Gomà-Rodríguez et al., 2018).

Practicing this type of activity involves a strong emotional mobilization, though, as appointed by a study, the involvement of professionals engaged in dealing with cases of violence against women in an intersectoral network. The results indicated that the respondents perceived their work as exhausting and experienced many doubts, feelings of impotence, sadness, anxiety, distrust, frustration, discouragement, stress, and fear, given the cases attended. Another occupational risk for workers’ health in this type of service is secondary traumatic stress (Vieira & Hasse, 2017).

This syndrome is characterized by cognitive, emotional, somatic, and motor reactions, such as intrusive thoughts, insomnia, hypervigilance, and feelings of emptiness and hopelessness, among others (Caringi et al., 2017). A systematic review pointed out the differences in susceptibility to secondary post-traumatic disorder in physicians from child protection services, family violence, and sexual abuse care centers, and care for disaster survivors. It concluded that there is a propensity for the occurrence of this illness in female professionals whose explanations point to one of these aspects: a greater chance of women have already been victims of violence at some point in their lives, and a greater tendency for them to report suffering excites (Baum, 2016).

Thus, given the potential risks to the health of professionals and staff involved in providing services to victims of violence, self-care is suggested as a resource against these diseases and to preserve health. This term refers to a set of daily human practices which reflects the strengthening of skills, and actively promoting health care, whether in the individual or collective scope (Cantera & Cantera, 2014). At an individual level, self-care practices are developed through actions aimed at maintaining physical and mental health, such as careful meal composition, quantity and times, physical activities, sleep, participation in leisure activities, development of cognitive stimulation activities, preservation of good communication with important bonds (family, friends, co-workers) and implementation of self-observation disposition to manage one’s own behaviors (Sepúlveda et al., 2014).

Within the professional teams, the incorporation of self-care is materialized through the creation of spaces to address the following latent themes for the practice of this type of service provision: the work burden and surplus work and how these affect the development of activities, impotence/omnipotence mobilized in the approach of the cases served, and affective overidentification with the reports assisted. In addition, these environments represent opportunities to organize, delegate, and coordinate activities within the group, developing a sense of trust among professional team members. These proposals offer benefits for professionals as well as communities by avoiding the reproduction of violence in the very care for the targets served (Holguín & Velázquez, 2015).

The work of art has the potential to release feelings, as well as facilitate a sharing of connection with their peers and, thus, reducing group stress, emerging more positive feelings. The results of an intervention proposal, within a qualitative and quantitative methodology construction, pointed out that a social action art therapy intervention reduces participants’ stress, as measured by the results of post-intervention research (Ifrach & Miller, 2016).

Another form of action to preserve these professionals’ health was proposed through a quantitative and qualitative exploration in the United States. The intervention was promoted by including professionals allocated to adult care services for survivors of child abuse, sexual assault, and violence against women from four community organizations in the holistic healing arts retreats characterized by a focus on the present, empathy, acceptance, and positive regard for the other. Different physical and emotional variables were measured before and after the intervention to investigate the effects of this proposition. After participating in these retreats, there was a decrease in the levels of insomnia, symptoms of secondary traumatic stress disorder and depression, perceived stress, an increase in life satisfaction, levels of physical and bodily esteem, attention to self-care, and self-efficacy (Dutton et al., 2017).

Taking into account the expansion of assistance centers for women in situations of violence and the occupational risks described in care for victims of violence against women, and the relevance of incorporating self-care as a health maintenance resource for these workers, it becomes relevant to carry out studies on the work situation of professionals assisting women victims of violence. This paper will present a comparative picture of the primary data from research carried out through a partnership between the Federal University of Sergipe and the Partner and Workplace Violence research group of the Autonomous University of Barcelona based on the following objectives: to describe the working conditions, investigate the experience of attending to female victims of violence and observe the self-care practices the professional group practiced at the personal, professional, collective, and institutional levels.

2. Method

This cross-sectional and descriptive research was carried out in care centers for women victims of violence in Brazilian and Spanish territories. Convenience samples were constructed, adopting the following inclusion criteria for participation in the research in the two countries: (a) to work in the centers for women victims of violence; (b) to be linked to the psychological, social, or legal assistance of cases of women victims in specialized services; and (c) to be available to participate in the research.

The sample of this cross-cultural study consisted of 32 subjects working in care for victims of violence against women. Thus, in the Spanish context, this sample consisted of 20 professionals, 18 women, and two men, in this area with an average age of 47 years, who work at different care centers of public and private associations in Spain. In Brazil, the sample consisted of 12 female professionals, with a mean age of 35 years, from four care centers for victims of violence against women in the city of Aracaju and the interior of Sergipe.

In Brazil and Spain, representatives of the care centers for cases of violence against women intermediated contact with the participants to map the number of professionals who specialized in offering services this kind of service and who were willing to participate in this study. The instrument used in both countries was an interview script with 15 questions concerning statements about violence, conflict and work, and self-care. The study started after the participants had signed the free, prior, and informed consent form, which contained a brief description of the purposes of this research.

In addition, thisstudywasapprovedbythe Ethics Committeeofthe University Hospital of Aracaju/Federal University of Sergipe, according to CAAE 82003917.5.0000.5546. In Spain, the information is anonymous and confidential, following the Organic Law 3/2018 and the ethical requirements of the European Union safeguarded by the research institution (Autonomous University of Barcelona).

After this stage, the date and place were arranged with the care professionals for victims of violence against women to conduct the interviews. The interviews were recorded with an electronic recorder, and the researchers later transcribed the content. The data collected in the two studies were separately submitted to the software Iramuteq.

This computer method allows the manipulation of a large volume of texts, identifies the context in which words occur, and presents different forms of textual analysis, resulting in an understandable and clear organization of the collected written material. Iramuteq provides the following textual analyses: textual statistics, specificities, correspondence factor analysis descending hierarchical classification (DHC), similarity analysis, and word cloud (Souza et al., 2018).

For this research, the DHC, Reinert’s method, was chosen for being an analysis that fragments the text or text corpus into text segments. The text segments represent text fragments, and their size is usually three lines, estimated by Iramuteq, depending on the text. These segments are classified according to their vocabularies, and their grouping is divided according to the frequency of reduced forms (Camargo & Justo, 2013).

DHC results from a correlational logic that uses the segmentations of the text corpus, together with the list of reduced forms and the computer program’s adapted dictionary, to represent a hierarchical classification scheme. Classes of text segments have vocabularies similar to each other, significantly associated with that class, and distinct from text segments of other classes (Camargo & Justo, 2013).

This analysis allows for mapping representation systems and organizing the vocabulary in classes in a tree diagram that clarifies their relations (Souza et al., 2018). In this way, DHC makes it possible to track and organize the vocabulary extracted from the transcribed interviews, presenting representative classes of the ideas that the textual corpus conveys.

3. Results

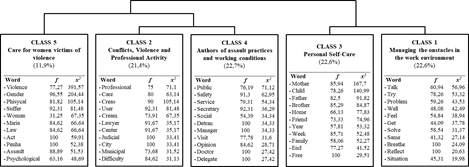

Data analysis was extracted from the interview script applied in the Brazilian context using DHC. This analytical procedure allowed us to track and organize the transcribed vocabulary into the most quoted words and their chi-square (x2), arranged into five classes representative of the ideas the text corpus conveys (Camargo & Justo, 2013).

For this, DHC generated a 12 initial context units that matchs to the interviews corpus. These were divided into 1,283 text segments, corresponding to 86.13% of the text material, an acceptable level of material utilization, whose value needs to be higher than 75%, and 4,177 words, with a frequency of 10,51 words per response. The constructed tree diagram, based on the similarity of the text segments, presented five classes of text segments. Through the “profiles” tab, the lexical contents of each of these classes are verified (Souza et al., 2018).

The words displayed in each class of the tree diagram correspond to the first 10 words exhibited in each class. The reports of the investigated words or text segments demonstrated in this comparative analysis were taken from the “profile tab” so that the scenario of each class is presented by text segments specific to the investigated reality.

This DHC divided the corpus’ five classes into three subcorpora so that, on the one side, Classes 5, 2, and 4 are shown and, on the other, Classes 1 and 3. Next, Class 5 was separated into Classes 2 and 4 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Tree diagram of descending hierarchical classification for the corpus “work of professional caregivers for victims of violence against women in Brazil”

As shown in Figure 1, the corpus “work of professional caregivers for victims of violence against women in Brazil” consists of five classes. Hence, Class 5, called “care for female victims of violence”, corresponds to 11.9% of the text segments and presents dis- course referring to aspects related to the attended demand and the contact with this reality. The following words are representative of this class: “gender” (f = 92.55%), “suffer” (f = 92.31%) and “violence” (f = 77.27%).

The segments from the interviews in Class 2, called “conflicts, violence and professional activity”, corresponding to 21.4% of the text segments, identify the characteristics of the situations of conflict and harassment and describe the obstacles faced by the professionals’ activities. The following words are representative of this class: “user” (f = 92.31%), “center” (f = 91.67%) and “difficulty” (f = 84.62%).

The reports in Class 4, entitled “authors of assault practices and working conditions”, corresponding to 22.7% of the text segments, denote these professionals’ precarious working conditions and the hierarchical superiors’ abuse of power. The following words represent this class: “manager” (f = 100%), “secretary” (f = 92.31%) and “safety” (f = 91.30%).

The excerpts in Class 3, designated “personal self-care”, portrayed in 22.6% of the text segments, outline the space and time available for this purpose. The words “mother” (f= 85.94%), “brother” (f = 85.29%) and “friend” (f = 75.33%) represent this class. Lastly, the excerpts in Class 1, “managing the obstacles in the workplace”, based on 22.6% of the text segments, characterize how professionals deal with conflicts, difficulties, and other issues related to the relationship between professionals and the compliance with the demands received in the work context. The following words are representative of this class: “breathe” (f = 100%), “reflect” (f = 100%) and “try” (f = 78.26%).

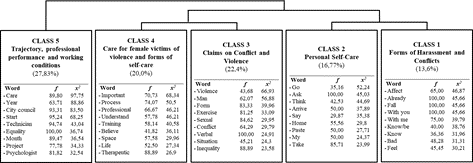

On the other hand, the data analyzed in the Spanish scenario, using the DHC, were arranged in 20 initial context units that matchs to the interviews, organized in 1,304 text segments, corresponding to 90.11% of the text material and 5,188 words, with a frequency of 15,29 words per answer. The elaborated tree diagram followed the same construction criteria explained in the DHC of the Brazilian context (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Tree diagram of descending hierarchical classification for the corpus “work of professional caregivers for victims of violence against women in Spain”

Thus, the words presented in each class correspond to the first 10 exhibited in each category, and the statements extracted for this comparative construction were selected according to the characteristics of the reality described. The corpus of this tree diagram was divided into two subcorpora. On the one hand, Class 5, and on the other, Classes 4, 3, 2, and 1. In the next step, the second subcorpus was divided into two (second partition), showing Class 4 and 3 on one side and Classes 2 and 1 on the other.

The corpus “work of professional caregivers for victims of violence against women in Spain”, as presented in Figure 2, consists of five classes. Thus, the excerpts in Class 5, entitled “trajectory, professional performance and working conditions”, corresponding to 27.83% of the text segments, report on the practice, these workers’ professional trajectory, and work circumstances. The following words are representative of this class: “start” (f = 95.24%), “technician” (f = 94.74%) and “care” (f = 89.80%).

On the other hand, the excerpts in Class 4, entitled “care for female victims of violence and forms of self-care”, corresponding to 20% of the text segments, include the characterization of the respondents’ precarious work situation, the self-care forms the professionals promote at the personal level and the characteristics of this care at the institutional level. The words “process” (f = 58.15%), “therapeutic” (f = 88.89%) and “training” (f = 83.33%) illustrate the class.

The excerpts listed in Class 3, entitled “claims on conflict and violence”, based on 22.04% of the text segments, address the elements and nuances characteristic of the attended women’s violence situations and the situations the Spanish professionals experienced within the work context. The words “verbal” (f = 100%), “sexual” (f = 84.62%) and “form” (f = 83.33%) represent the class. The statements in Class 2, then called “personal self-care”, based on 16.77% of the text segments, address the personal and social mechanisms to preserve health. Representative of this class are the words: “ask” (f = 100%), “take” (f = 85.71%) and “home” (f = 55.56%).

Finally, the excerpts in Class 1 exposures, labeled “forms of harassment and conflicts”, corresponding to 13.6% of the text segments, point to the practices, authors, and consequences of the conflicting and aggressive situations in the work environment. These are illustrative words of this class: “fall” (f = 100%), “bad” (f = 48.28%) and “feel” (f = 45.45%). Thus, this discursive analysis will pair the findings of the classes in the Brazilian and Spanish corpora to indicate and discuss similarities and differences.

4. Discussion

The results of this comparative study have demonstrated similarities in terms of work conditions, experiences of harassment at work, the lack of institutional self-care, and the experience of attending to victims of violence against women among professionals assisting victims of violence against women the woman in Brazil and Spain. On the other hand, there are differences in recognition of the occupational risks inherent to the activity of attending to victims of violence and in the forms of personal self-care.

Class 4, from research in Brazil, and Class 5, from the Spanish dendrogram, reveal the working conditions of professionals from specialized centers in their respective countries. When comparing the percentage of text segments related to this theme between the two countries, a higher percentage of text fragments in Spain was identified. Spanish professionals are subject to precarious forms of work characterized by weakening contractual relationships, burden, long work hours, and low remunerations. This picture refers to a scenario characteristic of the female workforce as women, that made up a large part of the participants interviewed in Spain, are more exposed to precarious and informal forms of work, reflecting the sociocultural deployment of the sexual division of labor, in which monotonous and domestic activities of lesser social prestige are attributed to women (Braga et al., 2019; O’Keefe & Courtois, 2019).

According to the participants’ discourse, in the Brazilian context, these precarious work conditions are mostly related to the lack of physical infrastructure, availability of human and material resources, security, and disarticulation of the network for care to victims of violence against women. These issues are also highlighted in the Observe reports (Pasinato, 2011; Rocha et al., 2010).

The precarious work context of professionals working in centers for women in situations of violence in Brazil and Spain reflects the acceleration of the individualization processes of contemporary Western societies, which rejects the construction of collective spaces for discussion and exchanges as recommended as a form of personal and institutional self-care. Furthermore, the value hierarchies within this type of society lead to the denial of the possibility of recognizing some essential activities, especially those with non-productive characteristics (Mendonça, 2016).

In addition to precariousness, Brazilian and Spanish professionals are confronted with harassment practices, as in Class 2 in the dendrogram in Brazil and Class 1 in the DHC in Spain. These practices are represented by devaluation, isolation, and denial of communication, exercised by hierarchical superiors, a characteristic circumstance of rigid and hierarchical structures (Freitas et al., 2008). There appears to be a higher percentage of text segments related to the issue of conflicts and practices in Brazil. This form of institutional management raises obstacles for Brazilian professionals to accomplish the activities, generating feelings of frustration for the workers. This reality becomes yet another factor of illness for this group of Brazilian participants.

It is observed that the managers of these services for women victims of violence do not fulfill the role of managing conflicts and promoting self-care of the institutions for women victims of violence workers (Sansbury et al., 2015). This institutional role is also described by a study carried out in the United States in care centers for women victims of violence, which pointed out how cultures and practices in the workplace, encouraged by the institution, influence the self-care practice of workers (Cayir et al., 2020).

In the same comparative sense, statements from Class 5 in the Brazilian context, and Class 3, identified in the Spanish research, with a similar percentage of text segments, point out the specific emotional experiences of attending to victims of violence. The provision of services to listen to and welcome female victims of violence causes feelings of impotence, insecurity, discouragement, and exhaustion in the Brazilian and Spanish professionals who have contact with this reality. This finding aligns with different research results (Dworkin et al., 2016; Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2016; Vieira & Hasse, 2017) that indicate the psychosocial risks inherent to this type of experience.

By combining similar findings from the Brazilian and Spanish scenarios, one identifies how the presence of the rigid and hierarchical institutional figure lays the ground for mental illness due to the lack of attention to conflict resolution and to the management of the psychosocial risks inherent in providing services to victims of violence against women. Although the same feelings and experiences cross the Brazilian and Spanish professionals in their contact with battered women, there is a significant difference in recognizing the occupational risks of this activity and adopting individual self-care practices between Brazilian and Spanish professionals.

In Class 4, identified in the Spanish context, all professionals, who did not occupy management positions, were found regarding both the knowledge and identification of forms of illness and burnout, and secondary stress disorder (Oliveira, 2015), as well as statements about the individual experience of these psychopathologies. This scenario was not identified in the Brazilian research context, as in Class 1.

In general, it appears that the institutions do not prioritize the psychological wellbeing of professionals in care centers for women in situations of violence, failing to provide resources for the practice of good self-care (Jirek, 2020). The Spanish workers’ identification of occupational hazards makes them seek forms of care for their own health, such as participation in psychotherapeutic processes. This difference between Brazilian and Spanish professionals in self-care also figures at the individual level, as will be discussed next.

The self-care of the professionals surveyed is represented by Class 3, from Brazil, and Class 2, from Spain, with a higher percentage of text segments in the Brazilian survey. The self-care of the Brazilian workers is linked to the support networks, mainly consisting of the family members, such as a mother figure, child, and husband, and with little time available for self-care. For female professionals in Brazil, the family environment is a highly relevant source of security and support, constituting a very impacting source of social support.

This support modality is considered the source of interpersonal relationships that enable feelings of protection and support, generating the feeling of acknowledgment, care, and acceptance, as well as the support that grants the conditions to face daily stress (Campos, 2016). Recognizing the social support within the family environments and the unavailability of time for self-care points to the confinement of these women to the private and family spaces and privatization of their time and space in care for the home and/or other people. This scenario reveals the Brazilian strongly male-dominated culture that models and imprisons women in staunched and private social spaces and roles (Saffioti, 2011).

The Spanish professionals’ self-care is found in physical activities, which they consider as a way of recognizing the problems experienced more clearly, strengthening and maintaining their mood, or even valuing the exercise itself. Physical activity and care for the body-mind balance are characteristic actions of individual self-care (Brady, 2017; Posluns & Gall, 2019).

The self-care bases of the Spanish professionals are based on identifying and recognizing their subjective experiences, which permit personal empowerment and better management in providing services to the clients served and in the relationships with other agents in their workspaces. That is because, through this self-empowerment, they establish limits, intervene and respond within the contact with the clients and co-workers in an assertive, active, and safe spectrum. In order to preserve their health and minimize the impacts of this type of activity, the Spanish professionals resort to individual forms of self- care, understood as a set of actions and practices aimed at promoting health and quality of life, exercised individually or collectively (Taylor et al., 2018; Velázquez et al., 2015).

This confinement of the Brazilian participants becomes more latent when compared with the findings concerning this same aspect for the Spanish workers, as highlighted in the confrontation between the self-care findings of Classes 3 and 2. It is noted that the participants in Spain have greater autonomy over their time and space so that they undertake actions focused on themselves, as illustrated by the quote: “establish some spaces. More or less basic, for me therapy is sacred” psychotherapy, therefore, is a space for recognition of their subjective experiences (Correa, 2015).

As scored in the comparison between Classes 1 and 4, the lack of knowledge about the occupational hazards involved in the practice of this type of activity and the institutions’ retreat from addressing the Brazilian female workers’ health are significant issues that reveal a combination of more illness-causing elements in the Brazilian than in the Spanish context. In addition, this picture points out that the professionals working in the care for victims of violence against women in Brazil do not possess comprehensive training concerning self-care or knowledge about the occupational risks intrinsic to helping relationships (Oliveira, 2015). However, as highlighted above, the institutions do not support the self-care of Brazilian and Spanish professionals. It is a context in which the attribution of responsibility for self-care occurs at the individual level.

The results associated with the exercise of listening to cases of women victims of violence demonstrate how the activity of attending to victims of violence evokes a strong emotional mobilization for the participants in Brazil and Spain. In addition, it indicates how these professionals are impacted by institutional difficulties that generate contexts of conflicts, violence, and losses in these professionals’ health. On the other hand, the male-dominated system clearly demarcates the Brazilian female workers’ spaces, attitudes, and time regarding individual self-care practices. However, at this point in the discussion, it should be noted that the Spanish female workers are also immersed in this same male dominance and patriarchalism, whose expressions differ from the Brazilian variant. It is marked by subtlety, imprecision, and performance at the micro level, such as the lack of financial benefits institutions offer for funding self-care activities (psychotherapy and physical activities) mentioned by professionals in Spain.

5. Final Considerations

The analysis carried out reveals the existence of similarities between Brazilian and Spanish female professionals concerning the emotional mobilization in response to the cases attended and the experience of conflicts, violent and illness-causing relationships due to rigid hierarchical structures that do not pay attention to the inherent risks of care for victims of violence against women. On the other hand, these approaches are also present when it is detected that the obstacles to Brazilian female workers’ professional performance are mainly located in structural work conditions. In contrast, Spanish professionals are more exposed to precarious work conditions characterized by work burdens, long hours, and low remuneration.

The differences take the form of attention to self-care issues. It is observed that the participants in Spain recognize the risks inherent in the activity and seek individual self- care actions focused on empowering their subjective experiences and activities focused on their well-being. On the other hand, the participants in Brazil do not recognize the harm the practice of this activity causes due to the lack of professional training focused on health care in the practice of aid relationships. This scenario is also determined by sociocultural factors and characteristics of the Brazilian job market, which lead workers to perform their work activities to the detriment of their health. Moreover, these workers’ personal self-care practices are characterized by confinement in family spaces and the lack of time and space for individual and private self-care practices.

This investigation represents an unveiling of the subjective experiences of workers involved in the care for victims of violence and the institutional difficulties these professionals face, which foster violent relationships and limit the spectrum of care for the attended female clients. This way, this study demonstrates how the participants in both countries are deprived of institutional self-care. It also addresses the importance of self- care in professional training in this field and reflects how sociocultural and labor market aspects are potential modelers of self-care practices.

It is known that the state, in the neoliberal context and the removal of collective issues in Brazil and Spain, promotes a maximization of occupational risks for these professionals that is operationalized by exposure to precarious working conditions, without labor guarantees, based on a personalistic management model and little or no attention to the health of these workers.

Therefore, this framework maximizes the vulnerability of professionals who assist victims of violence against women. Indirectly, it also weakens those assisted by this service since the illness of the team and its members affects the quality of the services provided.

We conclude that the self-care of the professionals allocated in specialized services for women victims of violence is linked to the ways of managing and caring for the workers’ physical and mental health by the institutional managers and to social and cultural factors, such as the patriarchal system. That is due to the lack of systematization of practices and public policies aimed at promoting the health of these workers in the two countries researched. Therefore, it becomes fundamental that public and non-public organizations, such as unions and associations, mobilize their efforts to implement public policies aimed at the mental health of these professionals.

The following limitations can be listed in this study: (a) professionals allocated to health services, such as hospitals and health clinics, who attend battered women, were not interviewed; (b) absence of questions exploring symptoms of burnout syndrome and secondary post-traumatic stress disorder; and (c) absence of respondents allocated to management positions.

text in

text in