Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista Lusófona de Estudos Culturais (RLEC)/Lusophone Journal of Cultural Studies (LJCS)

Print version ISSN 2184-0458On-line version ISSN 2183-0886

RLEC/LJCS vol.8 no.2 Braga Dec. 2021 Epub May 01, 2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/rlec.3483

Thematic articles

Workers With Down Syndrome: Autonomy and Wellness at Work

1 Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil

2Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil

3Instituto de Psicologia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil

This article presents a research report that was replicated in the city of São Paulo (Brazil) of the one developed in Portugal by Veiga and Fernandes (2014). It reflects on some research data, which demonstrate the role, importance and impact of being admitted in the world of work in the lives of workers with Down syndrome, including the feeling of wellness, autonomy, and friendship acquired. These workers were interviewed, as were their immediate bosses, friends and co-workers, and the observations made at the workplace. Knowing that social inclusion does not occur outside work, we highlight the importance of public policies in promoting rights and defending the rights already achieved, including the active participation of people with Down syndrome in society. This study showed that the achievement of a job made it possible to increase self-esteem, to develop autonomy and wellness of workers, providing them with achievements in the affective-social field (dating and friendships), in the family, economic and professional spheres, albeit with restrictions. The job also provided the feeling of being more useful and accepted by peers (“a sense of belonging”). It also allowed the possibility of contributing to the family and making plans for the future, with the same projects as any young adult, such as travelling, getting married and having children.

Keywords: autonomy; wellness; intellectual disability; labor market; inclusion

Este artigo apresenta o relato de uma pesquisa que foi uma reaplicação na cidade de São Paulo (Brasil) da desenvolvida em Portugal por Veiga e Fernandes (2014). Reflete sobre alguns dados obtidos, os quais demonstram o papel, a importância e o impacto do ingresso no mundo do trabalho na vida de trabalhadores com síndrome de Down, incluindo o sentimento de bem-estar, de autonomia e as relações de amizade adquiridas. Foram entrevistados não apenas esses trabalhadores, mas também seus chefes imediatos, amigos e colegas de trabalho, e foram realizadas também observações nos locais de trabalho. Sabendo que a inclusão social não se concretiza de modo alheio ao mundo do trabalho, destacamos a importância das políticas públicas, quer na promoção de direitos, quer na defesa dos direitos já conquistados, inclusive o da participação de pessoas com síndrome de Down na sociedade. O resultado deste estudo evidenciou que a conquista do emprego possibilitou o aumento da autoestima, o desenvolvimento da autonomia e do bem-estar dos trabalhadores, proporcionando-lhes conquistas no campo afetivo-social (namoros e amizades), nos âmbitos familiar, econômico e profissional, ainda que com restrições. Além disso, o emprego propiciou a percepção de se sentirem mais úteis e aceitos pelos pares (“sensação de pertencimento”), bem como a possibilidade de poderem contribuir para a família e de traçarem planos para o futuro, com projetos semelhantes aos de qualquer jovem adulto, como viajar, casar e ter filhos.

Palavras-chave: autonomia; bem-estar; deficiência intelectual; mercado de trabalho; inclusão

Introduction

Firstly, it is worth noting that the data and the analysis presented in this article stem from the chapter “Autonomia e Bem-Estar Após o Ingresso no Mundo do Trabalho” (Autonomy and Well-Being After Entering the World of Work), from the book InclusãoProfissional e Interação Social de Pessoas com Deficiência Intelectual (Professional Inclusion and Social Interaction of People with Intellectual Disabilities; Crochick, 2019), which reports the research conducted between 2017 and 2018 in the city of São Paulo involving workers with Down syndrome. The respective research was guided and coordinated by José Leon Crochick, with the participation of the members of the Laboratório de Estudos sobre o Preconceito of the Institute of Psychology of the University of São Paulo, and funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (Crochick, 2019).

According to Pereira-Silva et al. (2018), the inclusion of workers with disabilities in the labour market is a guaranteed constitutional right; however, the reality in Brazil is different when we verify the quality and working conditions that companies offer to these people, in addition to the high number of such workers who are still unemployed in the country. Even as corporate practices related to social responsibility increase, the adaptation of corporate environments to welcome and respect diversity needs to be significant ly improved. Still, for Pereira-Silva et al. (2018), the inclusion of workers with intellectual disabilities in the labour market has been more satisfactory than unsatisfactory.

In this article, we organise the research results with regard to the consequences in the lives of the participating subjects of being admitted into the labour market, based on interviews and observations. Thus, we surveyed whether employment affected their lives, including their circle of friends, whether it brought about changes in existing friendships and whether it favoured new relationships. Regarding autonomy, we analysed whether participants began to organise, plan and manage their lives more actively after being employed and whether admission into the labour market led to changes in workers’ wellness, that is if after being employed, they began to feel and consider themselves happier and/or more satisfied people.

Justification

According to Leite and Lorentz (2011), the amount of research reported is small regarding workers with Down syndrome, which alone justifies this study.

Although we acknowledge this work bears the contradictions of the current capitalist society, subject to a series of questions, including humanitarian ones, it is undeniable that it is also one of the means that enable greater social inclusion and the possibility of having a more dignified life. Leite and Lorentz (2011) and Pereira-Silva et al. (2018) also point it out and highlight greater autonomy and new possibilities for activities. Work can provide the satisfaction of being recognised as important workers - with or without dis abilities - by the people who matter to them.

Work, however, can also be a source of suffering due to frustrations that it can create, such as colleagues hostility; dissatisfaction with working conditions and/or wages; sacrificing the time one could dedicate to more pleasurable activities or even the nonrecognition of one’s ability at work. Regarding the person with a disability, marginalisation or segregation may also happen at the workplace, as in school life (Crochick et al., 2013; Leite & Lorentz, 2011). On the other hand, the research carried out by Leite and Lorenz (2011) and Pereira-Silva et al. (2018) found, as will be seen later, a high degree of satisfaction for workers, their peers and families, by providing more autonomy and more personal wellness, as well as the development of skills essential for all aspects of life, such as time management - and, last but not least, in some cases, new friendships.

The research by Alves et al. (2019) in the chapter “Autonomia e Bem-Estar Após o Ingresso no Mundo do Trabalho” (Autonomy and Well-Being After Entering the World of Work) also found that, for people with Down syndrome, these advantages and frustrations also occur and can be alleviated, according to education, family support and, above all, the support of employers and colleagues. The research conducted by Pereira-Silva & Furtado (2012) also indicates the same trends for workers with intellectual disabilities in general: work improves the worker’s quality of life, depending on how much support there is from all. They also add that this improvement depends on individual abilities and obstacles to face and emphasises the importance of companies’ necessary support. These authors verified the importance that these workers attach to the activities arising from their jobs, as these provide greater satisfaction and personal autonomy. They also cite studies showing that the need to associate methods with the fulfilment of goals strengthens the possibility of thinking about life projects.

The laws that favour the employability of workers with disabilities are essential. However, Pires et al. (2007), and Leite and Lorentz (2018), argue that they are not enough, as there is a need for the recognition of these workers’ capabilities and to provide them, where appropriate, with access to vocational courses and financial support either from companies or the government.

The research by Veiga and Fernandes (2014), which we replicated in Brazil and resulted in the above-cited book, made many significant contributions to this area. Among them is the need to raise awareness of the appropriate behaviours for social coexistence and the help of teams specialised in mediating between workers with intellectual disabilities and their colleagues and bosses, since school education does not always prepare them for that.

The research’ objective is to verify whether the admission of young people with Down syndrome in the labour market led to a more satisfactory social life, increased autonomy regarding different activities and the opportunity to develop projects for their lives.

Method

Participants

The research that originated the data presented in this article, which was a replication with adaptations of the research conducted in Portugal by Veiga and Fernandes (2014), adopted the following method: it selected as participants 20 young people with Down syndrome who had been working in the same job for at least 1 year; one of them lost his job in the course of data collection. These participants were also joined in the study by one work colleague and one friend they appointed, their immediate bosses, family members and an educational counsellor or similar from the school institution where each participant graduated.

These workers ranged from 21 to 37 years old, of both sexes, and approximately half were trained in special institutions and the rest in regular schools and classrooms. In addition, 17 of these participants lived in neighbourhoods with a high human development index (HDI), and three in neighbourhoods with a medium HDI. These participants will be assigned the letter “P” plus a number to facilitate the exhibition.

Material

Interview scripts were used in the research developed by Veiga and Fernandes (2014), with some adaptations in vocabulary and format. The scripts for workers with Down syndrome were divided into six parts: (a) general characteristics; (b) social relationships and interactions; (c) psychological wellness and personal satisfaction; (d) employment; (e) personal skills; (f) integration into the community. The script of interviews with friends had questions about the importance of work and how it contributed to the autonomy and wellness of the friend with Down syndrome; the scripts addressed to colleagues and bosses were intended to check satisfaction of the worker with Down syndrome with work, autonomy, and self-satisfaction. The family members were asked, through script interviews, about the importance of the job for the family and worker and how work contributed to their relative’s autonomy and happiness. The researchers also observed these workers in their workplace to obtain data on their autonomy, performance and satisfaction at work.

Procedure

Data Collection

The workers with Down syndrome were indicated by Instituto Jô Clemente and Instituto Simbora Gente, both of which offer different kinds of activities for people with intellectual disabilities. The participants and family members were invited to participate in the survey by telephone; participants indicated friends to be interviewed, and permission was requested to interview colleagues and bosses at the workplace, where observations were also made. The interviews with workers with Down syndrome lasted around 1 hour and a half, and the other interviews generally lasted 45 minutes. The data were collected in person at the workplace and the relatives’ homes between 2017 and 2018.

Data Analysis

Quantifiable data were analysed using descriptive statistics such as frequency, mean and standard deviation, and Spearman correlation coefficients. For the qualitative analysis of the answers to the other questions, we used data from the different interviews to be contrasted and supplemented to achieve greater accuracy of what was researched and broaden the discussion. The primary reference used was the critical theory of society. We also used the HDI of the area where the participants with Down syndrome lived to infer their socioeconomic level.

Results

We now present some quantitative and qualitative data regarding the research conducted with workers with Down syndrome to understand if the insertion of these people in the labour market helped expand their circle of friends, their autonomy, wellness and life projects.

Circle of Friendships

Of the 20 participants, 13 reported that most of their friends are of the same sex, and 11 subjects reported having friends of approximately the same age. Concerning friends with intellectual disabilities, 12 subjects reported that their social circle included friends with intellectual disabilities, and 13 reported having friends who do not have intellectual disabilities. Regarding this last data, it is possible to assume that part of the sample is not segregated from socialising with all people with and without intellectual disabilities, as they have friends with no such disability. However, one may ask, and consequently investigate, whether the friends without intellectual disabilities are in fact friends, or simply colleagues, or even psychotherapists who support them, since the 41 friends mentioned by the participants are in the following profile: nine are work-related, one is a sponsor, one is a dance instructor, and one is also a psychologist. In addition, all the participants reported that they go out on weekends in the company of family members. We also found that 14 also go out with friends, 12 with colleagues from leisure projects, nine with a girlfriend or boyfriend, and six reported going out with other colleagues.

According to the data analysis, a significant part of respondents admitted that access to employment contributed positively to expanding their circle of friends. Indeed, we found that nine of the friendships the workers reported are work-related, as reported in the following statements: “before the job, I had fewer friends” (P.4); and “before I used to be very shy, I could not speak properly to people. I met some at work, too” (P.17).

It is important to emphasise that the new relationships reported by the participants were not restricted to the workplace but expanded to encompass places outside the work environment. In this sense, we observed the following data: 14 of the workers participating in the survey reported going out with friends, especially on weekends, and 12 reported going with friends to places or activities of leisure. Another relevant piece of data concerns the fact that 12 of the participants also report seeking the support of friends, especially when they are bored and/or need some kind of help. Considering that the other friends reported by the workers are not working colleagues, it can be noted that some of the new friendships were made in the work context and grew beyond.

Regarding insertion and activity in society, which grew and improved due to the new requirements arising at work, we found, remarkably, that the subjects began to frequent and/or travel to new spaces. When asked about their relationships, particularly social ones, the participants mentioned certain places they supposedly went to regularly. In this regard, participation in religious cults, local parties and going shopping were the activities that more than half of the participants mentioned in common. Considering cultural leisure, especially theatre and cinema, 17 of the participants reported going to such places, usually in the company of family members and friends, including those from work. Thus, we note that friendships promoted and strengthened in the workplace, when adequately articulated or integrated with previously established relationships, help strengthen and consolidate self-esteem and improve the quality of life and standard of living considerably.

When interviewing the workers’ families, it was possible to see a significant increase in friends. That is represented in the account given by the mother of a participant:

I think her relationship at home and outside has changed a lot. Her circle of friends and colleagues has grown. ( … ) She has more friends now, especially colleagues, but there are always those friends who are closer. ( … ) So, I can see that the work also made her circle of friends grow. (P.1’s mother)

The mother of one participant (P.6) was concerned about her son’s new relationships; though meant to provide the best development and protection, we must observe to what extent such concerns can generate conflict and even hinder the development of children.

Employers, co-workers and friends of workers with Down syndrome reported that they made new friends; many said they valued the relationship with these colleagues and stressed the importance of these friendships, which broaden their affective and social relationships. Despite this, some showed that, in some cases, these new friends are limited to the workplace: “he made friendships at work, we met each other here actually. ( … ) sometimes it was at parties, but we hardly go out together in our daily routine” (P.2’s friend). On the other hand, one of the employers reported:

I think it has improved in terms of friendships and relations with other people. At first, I saw that she was very introverted and suspicious like I said before. And today, she is much more extroverted and interacts with others more easily. (P.3’s employer)

Moreover, a third interviewee from the work team noted: “he made friends at work and sometimes he is invited to go to the movies with a colleague. He is happier. He has changed a lot since he started working” (P.9’s co-worker).

The above quote (P.2’s friend) suggests friendships are limited to the workplace, making us wonder if this is due to schedule incompatibility or a respectful and friendly interaction with these colleagues with intellectual disabilities that does not represent a bond of friendship. That does not exclude the importance of work for improving social life, as Pereira-Silva and Furtado (2012) pointed out, who claim interaction with other people is essential.

It is worth noting that the circle of friends did not change or grow for some participants, even after they started working. However, it became clear in the testimonials that even when the circle of friends did not grow, their relationship with co-workers was not bad. As pointed out by the employer of P.8, the participants retained their significant existing relationships, only adjusting the times when they go out and do things to the new schedules because of the working hours.

We also noted that some interviewees pointed out the influence of employment on their work relationships, even if such influence did not necessarily positively impact friendships. According to some reports: “he has friends at work. Sometimes it’s not a friend, but a co-worker” (P.4’s friend); “I have more colleagues at work, not more friends, I think because many people are still prejudiced about people with Down syndrome” (P.3).

This trend of responses is consistent with what Veiga et al. (2014) report:

friendships (although some alumni have made more friends after entering the workforce) are few, neither truly close nor allowing for sharing and intimacy. Many are merely superficial and circumstantial, with each person giving little of themselves to the other. (p. 230)

Autonomy

In addition to the growing number of relationships and friends, employment can also be an important opportunity for people with intellectual disabilities to develop autonomy since this development is connected to the ideals of independence, freedom and self-sufficiency.

One of the necessary kinds of autonomy is related to political issues. It is interesting to note that 16 of the 20 participants vote in the elections. The fact that they choose their political representatives may indicate that they are aware of the need to choose from the different destinies of society. When we observe that democracy is under threat, not only in Brazil and that the number of people who stop voting is large, most of these participants vote in the elections is striking.

The autonomy achieved by entering the labour market grows: in the organisation of one’s routine at home, by memorising the home-work route, when using money, and in daily life at work. The skills required from the subjects create challenges that can favour the development of initiative, accountability and independence, allowing them to plan, decide and take better care of their own lives, progressively decreasing the need for the help of third parties to perform their activities.

We emphasize that 19 of the 20 participants considered themselves more autonomous, self-assured and confident after being employed. In this sense, one of the reports is representative of this strong trend:

my parents supported me, and I joined the labour market, and for me, it was very good because I became more mature, I grew up in the job and became more autonomous, independent. I can handle things on my own. (P.1)

Most participants answered that they help keep the house clean and organised; half of them usually cook, and few use the washing machine. According to their relatives, 15 of the participants help with household chores. These data indicate that workers’ participation in household chores tends to focus on activities requiring less technical skill and planning, such as cleaning rooms and washing dishes.

Besides helping with household chores, we also found that many participants changed their self-care habits when they started working. More than half of them say they have autonomy for self-care activities. Although this is a general trend, it is worth highlighting that it seems more prevalent in setting up a sleep schedule on weekends and choosing clothes. As for the choice and time of meals, most reported they did not have autonomy and followed the instructions of parents or mediators in those matters.

Despite these limits, we notice that performing the activities in which they gained autonomy is related to the significant development of independence and responsibility after they were employed. Many relatives report such gains. Two answers illustrate this perception: “I notice that she has become a more independent person, more autonomous… this I attribute to the work” (P.1’s mother).

She has amazingly grown since she started working, she became more autonomous. She can handle things on her own. She worked as a young apprentice before, and since then, it has been great. ( … ) Having a job is important for her in those issues that I talked about, developing her autonomy, her growth. (P.7’s mother)

As noted, many of the workers with Down syndrome gained more autonomy in taking care of household chores and themselves, which is crucial for their own lives and family life. The interviewees were also asked about their leisure habits and the places they like to go to in their free time, also checking if this changed after they joined the labour market.

Participants seem to have autonomy about leisure time when deciding what to do in their free time and when friends invite them. This trend is similar to those indicated by Veiga et al. (2014), when they point out that workers have autonomy “in some issues related to household management of a more intimate and personal nature, what they want to do in their free time and what activities they want to do” (p. 209).

However, 17 of the participants reported that they need permission from their parents or guardians to go out and feel obliged to go with them when they go out, even against their will. It should be noted, according to Fernandes et al. (2014), that:

the strategy of parental guardianship does not contribute to improving their quality of life. This strategy seems to be based mainly on placing impediments against them leaving the house without family control, which prevents or hinders autonomy when creating social ties and friendly or romantic relationships, including potentially significant and lasting ones. (pp. 209-210).

Two employers, two family members, two friends and one co-worker further indicated the issue of scheduling, commitment and sociability as essential skills and attitude changes that were developed in workers, suggesting that the job may have brought more confidence, responsibility and independence.

It should be noted that an employer indicated how the aspect related to learning hierarchical rules could be understood as a means that contributes to increasing respect in relationships outside the family realm. Insertion in another context of social interaction, as is the case of work, sets the challenge for workers to understand the codes and rules in force in this context, which includes hierarchical relations, the difference between bosses and colleagues. If hierarchy as an end in itself is criticisable, it may be necessary as a means.

Approximately half of the participants use their money as they wish. The vast majority have a bank account and/or bank card, but only five deposit and withdraw their money. Some of the interviewees admitted that the autonomy gains are related to the remuneration for their work. For example, P.13’s mother and a friend reported that the workers began to take better care of their own money and spend it better after they started working. Similarly, a friend of one of the interviewees pointed out the issue of income and purchasing power that employment introduced: “I think it’s very nice for her to earn her own money, to be able to buy her things, go out, travel” (P.1’s friend). Commenting on the same aspect, the mother of one of the workers reported the following fact:

she can do things that probably we, with all the household expenses - I’m retired, he (her husband) is also, and I, working at school, know how it is? So she does things, and she can have her own life. In private classes, she wanted to study, but with a private teacher and at home. So the teacher comes and gives her lessons here, and she pays for them. She pays for them herself when she takes courses at the National Industrial Education Service. When we are no longer here, that gives us some security because she has her own job, and her sister will be there for her just as her support network, right? (P.19’s mother)

Admitting the pros and cons that wage autonomy has brought to the lives of her children, one of the mothers also highlighted the following aspect:

There is the upside and the downside. The upside is that she has initiative. She can go out and buy her things, travel. The downside is that she questions me when I deny her something; she says, “I earn my money”. (P.16’s mother)

Therefore, money is a significant element in the workers’ lives. It represents a way of securing their autonomy (either through purchasing power or the possibility of helping with household expenses). It stands out from the aspects discussed so far. It seems to represent a relevant challenge that those subjects are able to use their financial resources as autonomously as possible and with the minimum necessary support.

These gains can be seen through effective recognition directed to people with disabilities, either by their family members or by friends or other people workers consider important. The analyses by Pires et al. (2007) confirm that employment can positively influence these workers’ self-esteem, autonomy, and social recognition for how they are seen by others and by themselves.

The issue of mobility raises interesting discussions about the development of autonomy after employment. Regarding the ability to get around alone (transportation), two participants and a mother reported: “I always go by car ( … ) if they let me go to work alone, I would be able to come back” (P.12). Another participant said:

I go out alone, sometimes I go out with my mother, too. Because my mother wants me to travel with her; sometimes she wants to travel with me, so we do it; sometimes I can’t go because I am working, or because of my social group, Simbora, gente! (P.14)

About that, the mother of one participant also said:

he could be more (independent). ( … ) He could go swimming, for example; he could take the bus. But when he comes back in the evening, he is tired. I wish he were more autonomous. Then the guy says, “you should ride the subway more”. But to go where? Does he have a girlfriend, and that is why he needs to ride the subway? No, he doesn’t. (P.15’s mother)

Most participants do not have the autonomy to get around alone. According to friends, only three of the participants go to work or other places they need to, alone; eight go out at night, but only with friends, which suggests little autonomy to get around. This piece of data is reiterated by the relatives of the participants, which shows that only three of the interviewees go to work or other places alone. Nine participants go out at night, usually with a leisure group mediator.

We notice how the issue of mobility becomes very important for both the workers and their families. Take as an example P.13, who, once he started working, became more autonomous in managing money, mobility, dressing and feeding himself, although he still does not leave home unaccompanied for anything. That brings us to why this autonomy gain seems more delicate or even more complicated.

Sometimes, families feel that their children with Down syndrome are less autonomous than they consider themselves, as the family always insists on accompanying them on their routes. Despite the various gains in autonomy mentioned by the interviewees, the issue of mobility still needs to be highlighted, perhaps because it implies a greater separation between workers and their families and caregivers, mainly because they put themselves in a vulnerable situation when getting around a large city.

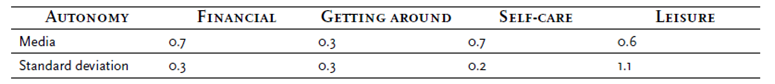

To compare the different types of autonomy, we calculated the indicators for each of the evaluated and presented them in Table 1. These indicators were calculated based on the various aspects analysed, ranging from 0 to 1.0: the closer to 1.0, the greater the autonomy.

According to the data in Table 1, participants have good autonomy in handling their finances, self-care and leisure, but little autonomy in getting around.

To know if there is a relationship between autonomy for mobility and the HDI of the participant’s area, we calculated Spearman correlations between this autonomy and the salary earned in the job. We found a significant correlation between autonomy for getting around and the HDI (r = -0.50; df 18, p = 0.03), suggesting that the lower the HDI of the district where the participant lives, the greater the autonomy to move; conversely, the higher the HDI, the lower the autonomy. Indeed, P.9 and P.14 have the highest indicators of autonomy. Both have life stories showing financial struggle; this seems to indicate that when the family is financially stable, they may overprotect their children with disabilities, thus preventing them from developing this type of autonomy. In addition, we also found a significant correlation between autonomy for getting around and salary (r = 0.45; df 18): the higher the salary, the higher the degree of autonomy for getting around.

Wellness and Life Projects

Besides the circle of friends and autonomy, joining the labour market can significantly affect the wellness of people with Down syndrome. We present below indicators from the interviews showing that working represents an achievement for these people, a reason for personal satisfaction, and how much this impacted their wellness.

Initially, we point out that in the answers to the questionnaires, all participants think they are happy, well-disposed people who like their lives. Furthermore, 19 of them say they are satisfied with themselves and think that the job has made them happier. Amongst the family members, the number is lower, but still, 12 family members think that the workers are happier after being employed. That shows that, generally, joining the labour market brings positive consequences for the feeling of wellness of the workers.

The testimonies indicate that many family members perceive the gains related to wellness, especially those related to being useful and the social inclusion of workers. These are crucial aspects for implementing an inclusion policy that goes beyond the insertion of people into jobs, thus allowing employment (and all the increased autonomy and engagement related to it) to promote greater social participation.

Another aspect related to the well-being of the interviewed workers is the way they see their present life compared to their prospects. This prospect raises from various visions, such as life plans, projects, dreams, desires and goals. In this sense, we notice that these workers have different ambitions, some of which have changed after being employed. Participants most often aim to: earn more, have their own home, get married, date and have children. These examples suggest no differences in the aspirations commonly attributed to young adults, as our participants can be described, according to their age.

Therefore, we can conclude that most have dreams and expectations instead of showing resignation as everyone does. In this regard, the answer given by P.1 that he wants a “more hectic” life strikes us, as it suggests both a feeling of monotony, possibly due to the few opportunities given to people with disabilities, and also their capacity for perception and criticism. Except for two participants, who think they will not be able to meet these expectations, and another one who thinks they already have everything they need, everyone believes they will be able to achieve what they expect for a better life.

According to the interviews with family members, 10 participants want to get married. In the accounts, two mothers of workers also reported that, after they started work ing, they began to make plans, set goals and consider new projects for the future.

In the described reports of some participants, we can detect how inclusion in work can rescue social participation in the sense of broadening their horizons and developing their dreams and expectations. We can identify a complaint that the company where they work does not allow them to perform other roles, even if those roles are part of the industry where they operate. From the point of view of professional inclusion, companies could rethink their practices and adopt actions to become even more inclusive, accepting the challenges that arise as the desires and ambitions of the subjects, who also become workers, grow.

One of the survey participants was dismissed while we were collecting the data. He said he considered himself happier when working and reported that being dismissed felt like a “kick in the stomach” (P.4).

Therefore, insertion in the labour market allowed the participants to feel better about many aspects of their lives. In cases where there was not much influence from the job, we noticed how the participants and the other assessed interviewees were already happy with themselves and their lives, so the job did not bring any visible negative or positive consequences. The negative points of having a job pointed out in three statements seemed to be related to routine and schedules, which is part of the working conditions of all people and constitutes legitimate frustrations, but not specific to the inclusion of people with disabilities.

Final Considerations

The data found in the reported research confirm a large part of the data obtained by the research by Veiga and Fernandes (2014).

We note that as people with Down syndrome joined the world of work, their social and affective relations were enriched and influenced, as highlighted by Leite and Lorentz (2011). In certain situations, encounters and bonds have become more solid friendships. However, we also observed reports where such ties were based on a relationship of affection and respect between colleagues. These observations were confirmed by 19 of the 20 participants in the survey, who reported being satisfied with their friends.

In some accounts, we noted a degree of reluctance or resistance on the part of some colleagues regarding workers with disabilities; however, as another relevant piece of data, it was possible to observe the engagement of other colleagues, a determining fact in the process of physical and social integration of employees in the workplace.

Many of the interviewees reported that the subjects developed autonomy due to their insertion into jobs. As we observed, 19 participants considered themselves more autonomous, secure and confident to deal with everyday situations. The data obtained by applying the questionnaires indicated that work brought about greater financial independence.

According to the accounts of family members, most participants in the research cooperate with household chores by performing tasks that require less planning and technical skill. According to the data, we also found a significant correlation between the workers’ autonomy to get around and the HDI of the place where they live: the lower the HDI where they reside, the higher their degree of autonomy to move. Most of the accounts also pointed out that employment resulted in increased well-being for workers with Down syndrome regarding the feeling of happiness and social participation and the self-perception of being helpful, accepted by peers, and able to contribute to the family to plan for the future.

Having a job increased self-esteem, autonomy, and wellness of the workers with Down syndrome interviewed in this survey due to the new experiences afforded by the jobs, which was also found in the research by Veiga and Fernandes (2014) and Leite and Lorentz (2011). We emphasise that the support of family, colleagues and bosses and previous training are crucial for the inclusion of these people, made possible and realised by access to employment, a fact which reverberates into other areas of social life, which is highlighted by Pereira-Silva et al. (2018).

Finally, we emphasise the importance of developing policies aimed at inclusion to strengthen actions that favour the admission of people with disabilities into the labour market, despite possible criticism of the capitalist mode of production and the exploitation inherent in this regime.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, which funded this study (Case no. 2016/19807-0).

REFERENCES

Alves, L., Corrêa, A. S., Correia, R. N. P., & Ventura, F. D. de S. (2019). Autonomia e bem-estar após o ingresso no mundo do trabalho. In J. L. Crochick (Ed.), Inclusão profissional de trabalhadores com deficiência intelectual na cidade de São Paulo (pp. 93-127). Benjamin Editorial, FAPESP. [ Links ]

Crochick, J. L. (Ed.). (2019). Inclusão profissional de trabalhadores com deficiência intelectual na cidade de São Paulo. Benjamin Editorial; FAPESP. [ Links ]

Crochick, J. L., Kohatsu, L. N., Dias, M. A. De L., Freller, C. C., & Casco, R. (2013). Inclusão e discriminação na educação escolar (1.ª ed.). Alínea Editora. [ Links ]

Fernandes, L. M., Veiga, C., & Silva, C. (2014). Autodeterminação e vida independente. In C. Veiga & L. M. Fernandes (Eds.), Inclusão profissional e qualidade de vida (pp. 189-210). Edições Húmus. [ Links ]

Leite, P. V., & Lorentz, C. N. (2011). Inclusão de pessoas com síndrome de Down no mercado de trabalho. Inclusão Social, 5(1), 114-129. [ Links ]

Pereira-Silva, N. L., & Furtado, A. V. (2012). Inclusão no trabalho: A vivência de pessoas com deficiência intelectual. Interação em Psicologia, 16(1), 95-100. https://doi.org/10.5380/psi.v16i1.23012 [ Links ]

Pereira-Silva, N. L., Furtado, A. V., & Andrade, J. F. C. M. (2018). A inclusão no trabalho sob a perspectiva das pessoas com deficiência intelectual. Temas em Psicologia, 26(3), 1003-1016. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2018.2-17Pt [ Links ]

Pires, A. B. M., Bonfim, D., & Bianchi, L. C. A. P. (2007). Inclusão social da pessoa com síndrome de Down: Uma questão de profissionalização. Arquivos de Ciência da Saúde, 14(4), 203-210. [ Links ]

Veiga, C. V., & Fernandes, L. M. (Ed.). (2014). Inclusão profissional e qualidade de vida. Edições Húmus. [ Links ]

Veiga, C. V., Fernandes, L. M., & Saragoça, J. (2014). Participação comunitária e satisfação com a vida. In C. V. Veiga & L. M. Fernandes (Eds.), Inclusão profissional e qualidade de vida (pp. 211-241). Edições Húmus. [ Links ]

Received: June 16, 2021; Accepted: September 22, 2021

text in

text in