Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Lusófona de Estudos Culturais (RLEC)/Lusophone Journal of Cultural Studies (LJCS)

versão impressa ISSN 2184-0458versão On-line ISSN 2183-0886

RLEC/LJCS vol.8 no.2 Braga dez. 2021 Epub 01-Maio-2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/rlec.3477

Thematic articles

Thematization of Disability in Children’s Literature - Perspectives on the Characters

1Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade Estadual Paulista, São Paulo, Brasil

2Instituto de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade Federal de Rondonópolis, Rondonópolis, Brasil

This study aims to discuss characters with physical disabilities in children’s literature. The discussion is relevant once the theme has been placed in books produced for children in Brazil, especially since 2008, with the National Policy for Special Education in the Inclusive Perspective (Decreto nº 6.571, 2008). Although the issue had already appeared in some literary works in earlier periods, usually with a stereotyped approach. Children’s literature publishers, faced with various institutional policies and programs, found a lode in the topic of special needs. Undoubtedly, social and political pressures for inclusion interfere in literary productions and their insertion in the school context. In this sense, analysing works that do not reinforce stereotypes or refer to disability as heroic overcoming, resignation and acceptance of fate, placing the characters in conditions of subordination and/or that inspire pity or divine will, can collaborate to broaden perspectives on what it is stigmatised as a disability as well as the limits and possibilities of the human being in different conditions and potential. Comparing children’s books that bring these two aspects - overcoming and accepting the real versus resignation and heroic overcoming - may help readers and children to understand the disability as part of normality and open good perspectives for discussion on the subject with these readers under training.

Keywords: physical disability; children’s literature; inclusion; text comprehension

O presente estudo se propõe a problematizar a representação de personagens com deficiência física em obras de literatura infantil. A discussão é relevante visto que a temática vem se colocando em livros produzidos para a infância no Brasil, principalmente a partir de 2008, com a Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva Inclusiva ( nº 6.571, 2008). Embora a questão já aparecesse em algumas obras literárias em períodos anteriores, geralmente com uma abordagem estereotipada. As editoras de literatura infantil, diante de várias políticas e programas institucionais, acharam um filão no tema das necessidades especiais. Indubitavelmente, pressões sociais e políticas de inclusão interferem nas produções literárias e sua inserção também no contexto escolar. Neste sentido, analisar obras que não reforcem estereótipos ou remetam a deficiência como superação heroica, resignação e aceitação do destino, colocando as personagens em condições de subalternidade e/ou que inspirem piedade ou von tade divina, pode colaborar para a ampliação de olhares acerca do que é estigmatizado como deficiência e os limites e possibilidades do ser humano em diferentes condições e potencialidades. Comparar livros infantis que trazem esses dois aspectos - superação e aceitação do real versus resignação e superação heroica - pode ajudar leitores e crianças a compreender a deficiência dentro de uma normalidade e abrir boas perspectivas de discussão sobre a temática com esses leitores em formação.

Palavras-chave: deficiência física; literatura infantil; inclusão; compreensão textual

Introduction

Literacy knowledge is essential for the development of children and young people. When we talk about experiences with literary texts, we show literature that is an art and, according to Coelho (2000), is synonymous with creativity that represents the world, humans, life through words. Children’s contact with literary texts can benefit their understanding of the world, ensuring that the literature adequately reflects the diversity of their experiences, as well as a sense of belonging to a social and real environment.

Price et al. (2016) reinforce that activities such as reading an infant literary text help build the reader’s vocabulary, oral language, and communication skills. From this perspective, Sonnenschein and Munsterman (2002) claim that it impacts literacy and vocabulary acquisition, supports other areas of development, such as children’s personal, social, and emotional features. Furthermore, we understand that reading infant literature allows children to learn new things about the world, remember events they already know, and relate their personal experiences to facts or episodes depicted in the books. In the same way, these young readers can learn about relationships and discuss diversity and differences.

For this to happen, the book market is full of books with different materials, genres, and themes that seduce children and young people.

Regarding materiality, some books are rich in covers and paratexts, showing the reader little secrets of the work, ensuring reader interaction. Souza and Bortolanza (2012) argue that the book “fulfils its irreplaceable and indispensable humanising function for the integral development of its personality” (p. 69), referring to the personality of the infant reader.

Another issue that can attract reading is the textual diversity that we can find on the shelves of bookstores, schools and public libraries. Texts and speeches can be perceived from the uses and functions they acquire in communicative situations. According to Machado (2014), contemporary children’s literature was inspired by various sources of the literary tradition, including oral ones and, therefore, the importance of identifying them.

Once children’s literature is the adjective that specifies its addressing, it was taken as a “genre” for a long time, which, in a sense, concealed the heterogeneity of genres that constituted it. ( … ) texts that we call “infant literature “have a wide range of literary genres that confirm this heterogeneity: fables, poems, short stories, legends, among others. (Machado, 2014, n.p.)

Approaches to literature for children and young people are varied and depend a lot on when the texts were written; that is, there is a thematic relationship with the political and social history of the country where the work was released. In Brazil, for example, the first writings for infant readers, produced at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, had as their theme a sense of pride and the ideal child - the wellbehaved, quiet, educated one. After that, Monteiro Lobato (1882-1948) inserted themes closer to childhood and placed children’s characters at the centre of his texts.

Nowadays, we find infant literature on any subject. Paiva (2008) mentions “reality as a bet” of the publishing market, that is, books that portray themes such as death, fear, separation, racial issues, feelings - subjects considered both delicate and controversial issues. According to the author, texts that explore this thematic axis take advantage of the contexts and scenarios of children’s daily life, allowing them to see themselves in history by associating their experiences with the plot, thus using their prior knowledge but still expanding the possibilities of understanding and meaning of the world, of others and themselves.

In this same theoretical perspective, Kirchof et al. (2013) notice that “in Brazil, since the mid-1990s, but especially in the 2000s, the growth of interest in themes related to differences have become noticeable in the broader social scenario, with consequences also in a wide range of productions addressed to children” (p. 1045).

Thus, children’s literature starts to thematise race, ethnicity, age, disability, sexual orientation, body conformation, and gender differences.

In this article, we will address physical disability and how characters with disabilities are represented in some works aimed at children.

Inclusion and Disability - Brief History of Legal Frameworks

In the history of people with disabilities, there is a long way for society to respect them and include them in social, educational and political contexts. Inclusion is understood by Freire (2008) as an educational, social and political movement supporting the right of all individuals to participate, consciously and responsibly in the society they belong to and to be accepted and respected in their difference (p. 5). In the educational context, it also defends the right of all students to develop and realise their potential and adjust the skills that allow them to exercise their right to citizenship through quality education, designed to account for their needs, interests and characteristics (Freire, 2008, p. 5).

Thus, the concept advocates the universalisation of human rights, emerging as a guiding perspective for public policies. We have been interested in showing some international actions aimed at including people with disabilities. To do so, we draw a short history of the legal frameworks regarding inclusive education.

In Brazil, the Federal Constitution establishes equality as a right:

Education, a right of all and a duty of the State and the family, will be promoted and encouraged with the collaboration of society, aiming at the full development of the person, his/her preparation for the exercise of citizenship and qualification for work. (Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil art. 205)

Among its educational principles, the equality of conditions for access and permanence in school is explained in Article 206, Subsection I (Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil art. 206, §I). In contrast, specialised educational assistance for students with disabilities is mentioned in Article 208, Subsection III, as an obligation of the State which must preferably be carried out in the regular educational system (Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil art. 208, §III).

In 2010, through Constitutional Amendment no. 65, Article 227 was redrafted, placing the fight against discrimination and promoting equality as a duty of all. In that same article, among its commandments, it reads:

II - the creation of prevention and specialised care programs for people with physical, sensory or mental disabilities, as well as the social integration of adolescents and young people with disabilities, through professional training and coexistence, provide access to collective goods and services, with the elimination of architectural obstacles and all forms of discrimination. (Emenda Constitucional nº 65, 2010, Art. 227, §II)

There have also been, throughout the world, movements to combat social exclusion and high levels of illiteracy. In this direction, under the coordination of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco), were held conferences and conventions from which essential documents have been published.

In Brazil, based on the Federal Constitution and international declarations, Ministry of Education Ordinance no. 1.793 was published, which recommended, in its Article 1, the “inclusion of the subject’ Ethical-political-educational aspects of normalisation and integration of person with special needs’, primarily in the courses of Pedagogy, Psychology and in all Degree Courses” (Portaria nº 1.793, 1994). It is important to emphasise that most of the degree courses mentioned did not meet this recommendation for various reasons this article will not address.

In December of 1996, Law no. 9.394 - Law of Guidelines and Bases of National Education (Lei nº 9.394, 1996) entered into force, which, in Chapter V, deals specifically with special education, which is understood as a “modality of school education offered preferentially in the regular network of teaching, for students with disabilities, pervasive developmental disorders and high abilities or highly gifted ones” (Art. 58).

Decree no. 3.298 (Decreto nº 3.298, 1999) states that “any loss or abnormality of a psychological, physiological or anatomical structure or function that generates incapacity to perform an activity, within the standard considered normal for human beings” (Art. 3, §1). That impacted the school environment because, by force of law, it began to compel educational systems (public and private) to receive students who sought the institution to enrol themselves. There was a reaction from professionals who argued that they had not been prepared to work with this “new” student profile. Moreover, the “inclusion” was carried out without providing most establishments with infrastructure, equipment, accessibility and other basic needs for the reception of students who required/require specialised care.

In line with this policy, in 2001, the National Guidelines for Special Education in Basic Education were published through Resolution CNE/CEB no. 2 (Resolução CNE/ CEB nº 2, 2001). It states that education systems must enrol all students, making schools responsible for organising the care procedures for those with special educational needs, ensuring the necessary conditions for quality education.

Hence, it sets as a principle to value and recognise the potentials and differences of people with disabilities, seeking, in the training and guidance of education professionals, to offer paths for inclusion, even though more in legal terms than concrete viability of conditions of access and permanence of those who needed/need specialised and personalised care.

In 2008, it was the National Policy for Special Education from the Perspective of Inclusive Education whose objective was: “to ensure the school inclusion of students with disabilities, pervasive developmental disorders and highly skilled/gifted ones, guiding education systems to ensure: access to regular education, with participation, learn ing and continuity at the highest levels of education” (Decreto nº 6.571, 2008, p. 14). In July, Legislative Decree no. 186 (Decreto Legislativo nº 186, 2008) approved the text of the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the optional protocol, signed in New York (30/03/2007). The decree provides the following definition of discrimination:

discrimination on the grounds of disability means any differentiation, exclusion or restriction based on disabilities, with the purpose or effect of preventing or precluding recognition, enjoyment or exercising under equal opportunities as other people, as well as jeopardising all human rights and fundamental dues at political, economical, social, cultural, civil or any other field. It comprises all forms of discrimination, even the refusal of reasonable adaptation. (Decreto Legislativo nº 186, 2008, Art. 2)

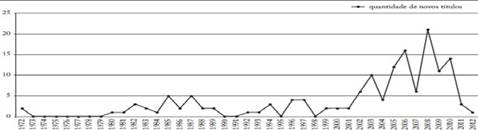

Amongst the fundamental points against the prejudice of any and all forms of discrimination, several actions impacted the production of materials aimed at this segment. An example can be seen in the research by Barros (2015), who surveyed 150 children’s books published from the 1970s to 2010 in Brazil, which depicted disability (Figure 1).

Source. From “Quarenta Anos Retratando a Deficiência: Enquadres e Enfoques da Literatura Infantojuvenil Brasileira” (Forty Years Picturing Disability: Framings and Approaches to Brazilian Children’s Literature), by A. S. Barros, 2015, Revista Brasileira de Educação, 20(60), p. 171 (https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782015206009). CC BY-NC.

Figure 1 Children’s books depicting disability versus year of first edition publishing.

The graph corroborates the argument that, despite some previous indications, notably from 2003, we have seen affirmative and inclusive actions in more significant numbers with the establishment of social and economic policies. The impact on editorial production is an example of this. A possible reason for the decrease from 2008 is that the Ministry of Education stopped buying books for Brazilian public schools, which has happened since 2013.

Given the scenario, in 2014, the National Education Plan (PNE 2014/2024) was approved, comprising 20 goals and strategies, specifically aimed at special education:

universalise, for people from 4 to 17 years old who present disabilities, pervasive developmental disorders, and highly skilled and gifted individuals, access to basic education and specialised educational care, preferably in the regular educational system. Besides, provide an inclusive educational system, multifunctional resources room, classes, schools, or specialised services either public or affiliated. (Lei nº 13.005, 2014, p. 55)

In 2015, the Brazilian Law of Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities (Statute of Persons with Disabilities; Lei nº 13.146, 2015) was approved, based on the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which must be inclusive and of quality in all educational levels; guarantee conditions of access, permanence, participation and learning, through the provision of accessibility services and resources.

Over the period we have presented as a time frame (1988-2018), it is possible to observe changes in legislation and enhancement of laws, plans and actions aimed at inclusive education. It is necessary to point out that the international declarations and reports were and are essential in strengthening it to guarantee the rights of people with disabilities and fight prejudice and discrimination.

These very rights must be expressed in literary books meant for children as long as we assume that literature forms the subject to respect differences and understand them. Thus, it is essential to verify how such characters are represented in literature for children and young people.

Characters With Physical Disabilities and Children’s Literature

We have already stated that children’s literature can help the reader’s development. According to Price et al. (2016), it can provide a context for understanding social norms and behaviours, helping children learn how to adapt to society, and facilitating the development of socio-emotional skills. Furthermore, children can obtain information from texts, learn how to link words and images, and understand perspectives that may differ from their own (Sipe, 2012). It is important to notice that literature is the main way children “see the world” (Flynn, 2001). Children’s books are a powerful means to promote children’s identity and understanding of several cultures, and literature can also lead its readers to understand and accept individuals who are different (Adomat, 2014). Sensitive or controversial issues in children’s literature books have taken up much aca demic research in several countries. Discussions on the depiction of gender, body size, individuals from different cultures and linguistic communities and individuals with dis- abilities are recurrent in children’s books (Price et al., 2016).

According to the authors (Price et al., 2016), such issues began to be inserted in children’s literature and analysed with more emphasis from the 21st century onwards. Although characters with disabilities have been the main characters in narratives in several countries since the 19th century, few empirical studies focus on how characters with disabilities are portrayed in children’s books (Prater, 1999).

Dowker’s (2013) study analyses characters with disabilities. The results showed that these characters are often depicted as limited in personality and lacking depth. According to Price et al. (2016), “the representations of characters with disabilities in these storybooks were largely inaccurate. For example, protagonists with disabilities were often portrayed as having received miraculous cures” (p. 564). Empirical studies have also examined how specific deficiencies are portrayed in literature. For example, children with intellectual impairment were mainly presented in supporting roles rather than as main characters (Prater, 1999).

Studies, especially English ones, show that, from 1990 and early 2000, there has been a positive trend in identifying characters with disabilities, as they appear in more inclusive settings. Price et al. (2016) claim that “in these books, characters with disabilities engage in typical everyday activities, including positive and meaningful interactions with their peers, their disabilities are not the focus of the story” (p. 564). Researchers (Dyches & Prater, 2005) have found that children with intellectual disabilities are often portrayed in supporting roles or as “protectors”, and their impairments are not pointed out.

However, although such research brings out results beyond stereotypes regarding physical disability, there is still a shortage of children’s books, whether English, North American, Portuguese or Brazilian, that positively depict characters with such disabilities.

In light of the above, it is essential to emphasise that in Brazil, according to Kirchof et al. (2013), “important research centres on children’s literature that in recent years, “important research centres on children’s literature discuss the issue of differences have been created” (p. 1048). One of these groups, Curriculum, Culture and Society Studies Nucleus (NECCSO) - coordinated by Rosa Maria Hessel Silveira, has collected children’s books whose theme is the difference. The list made by NECCSO from 2013 to 2016 has more than 700 titles that cover issues such as deafness, fatness, blindness, wheelchair users, death, gender and sexuality, the elderly, and others.

When we surveyed the texts that bring wheelchair users and people with physical disabilities, we found in the NECCSO titles only 29 works, including translations from Europe and North America. This reduced number of books only reinforces what scholars have affirmed in the research exposed.

To analyse children’s books, we sought the criteria and representations of disability based on a discussion prepared by North American researchers (Price et al., 2016), who observed the works as specific quality entities of disabilities depicted in the books.

Quicke (1985) emphasises the importance of representing characters’ physical appearance and behaviour by creating a generally optimistic tone through stories that reflect realism (Dyches & Prater, 2005). Characterisation, relationships with other characters, the level at which characters grow and transform, and characteristics of good practice in the field of special education form the basis for further analysis (Altieri, 2008; Dyches & Prater, 2005).

Altieri (2008) and other researchers (Price et al., 2016; Quicke, 1985) state that, when selecting a book, it is vital to question the terminology used in the disability descriptions and whether the character’s disability is quickly resolved or explained as an ongoing challenge. Furthermore, the researchers suggest verifying power dynamics in the relationships between the characters and who works as a “hero” in each story (Curwood, 2013).

Although each researcher presents specific ideas and focuses on literary topics, we can reach a consensus on what separates a positive picture of disability from an unfavourable one. Texts that contain stereotypes of representations of disability are rated as “inappropriate” (Beckett et al., 2010). According to the cultural model of disability, negative portrayals can also emphasise biological barriers to disability.

According to Beckett et al. (2010), characters are victimised, dependent, or objects of pity and, in this sense, the critical reader can consider the several character profiles with disabilities. The critical reader must then consider the role of the character with a disability in negative portraits. They can also serve just as examples of perseverance. The propensity of characters to act as leaders, problem-solvers, role models, and heroes continually relegate those with disabilities to inferiority (Hughes, 2012).

Another common feature of negative portraits is that characters with disabilities are granted almost superhuman attributes in an apparent attempt to compensate for their deficiencies (Yenika-Agbaw, 2011). Several professionals also agree that it is inappropriate for a character with a disability to be restored through a miracle cure (Dowker, 2013).

In addition to listing the story elements that form negative representations of disability, the researchers (Beckett et al., 2010) named features that contribute to positive characterisations. The most outstanding quality of characters is complexity; characters must have the dignity of depth and the freedom to evolve. In positive portrayals, characters with disabilities are depicted as individuals with unique personalities and interests (Hughes, 2012), and they are not disability-determined (Beckett et al., 2010). Researchers insist that children’s books about disabilities must be realistic to be acceptable (Beckett et al., 2010).

Many researchers also value the quality and accuracy of illustrations, so images of characters with disabilities must be free from stereotypes and bear positive physical descriptions in the text (Wopperer, 2011). Characters with disabilities must play various roles, serving as leaders, problem solvers, supporters, and heroes (Dyches & Prater, 2005; Wopperer, 2011). Texts showing positive characterisations present characters with independent disabilities, making choices and demonstrating self-determination. Stories must portray the appropriate inclusion of these subjects in society; they need to be given all the rights of citizens and find attitudes of acceptance by other characters and the community.

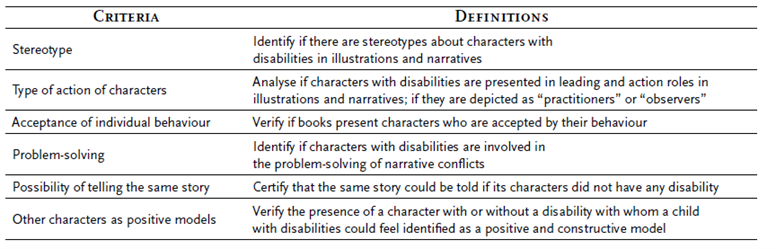

Considering the purpose of this article - to present some characters with disabilities and figure out how they are portrayed - we also provide below some criteria that helped us build a framework with guidelines for the analysis (Table 1).

Disability and Its representations

When we recall a character in Brazilian children’s literature who was presented with a physical disability, we immediately think of O Patinho Aleijado (The Crippled Duckling; Pimentel, 1952), a compilation and adaptation by Figueiredo Pimentel for Andersen’s tale The Ugly Duckling. In this Brazilianization of the Danish short story, an elaborate language distances itself from the real reader with clear intentions of nationalising the European collection (Zilberman & Lajolo, 1993).

The tale tells the story of an old duck that hatched some eggs after the ducklings were born, “all that was missing was the big egg, which, however, had no sign of being hatched” (Pimentel, 1952, as cited in Zilberman & Lajolo, 1993, p. 25). Although the other ducklings asserted that that egg must be from another animal and that this one is born and growing could eat the ducklings, the mother duck did not abandon the nest.

Seven days after the last duck came out, the old duck saw the big hatched egg, and an animal appeared, looking like a duck. It is true, but all crooked, dark and crippled.

Soon mother duck regretted having hatched such an ugly animal. But, as it had a good heart, and not wanting to let it go, showing her annoyance at disgraceful, disgusting duckling in its brood, the mother said nothing to her peers. (Pimentel, 1952, as cited in Zilberman & Lajolo, 1993, p. 26)

In addition to the duckling’s physical disability, the text shows in its outcome that, since its birth, it has suffered from “kidding, teasing, teasing, booing by every feathering gang” (Pimentel, 1952, as cited in Zilberman & Lajolo, 1993, p. 26). We could say that, as early as 1896, the character was bullied. In this story, physical disability is treated with prejudice, even by the mother duck, who “began to hate the cripple” (p. 26) because the duck community rejects its son.

However, the “crippled” character does not have the same attributes Andersen’s The Ugly Duckling has, but Pimentel ends the narrative by highlighting one quality of the character that could swim better than everyone else. In other words, although it stood out for swimming well, it probably lived alone, as it was not accepted by the band that rejected it. There are also signs of prejudice when the author attributes the “dark” colour and the “crooked” characteristic to the duckling.

Thus, we agree with Dowker (2013) when stating that “the way disability was represented in 19th-century fiction is quite complex. Some characters are portrayed flatly, as villains or, more often, as pitiful characters” (p. 1054). And, this is the case of O Patinho Aleijado (Pimentel, 1952).

We ask next is whether the depiction of characters in the 21st century has changed. How are characters with physical disabilities portrayed in contemporary Brazilian children’s literature?

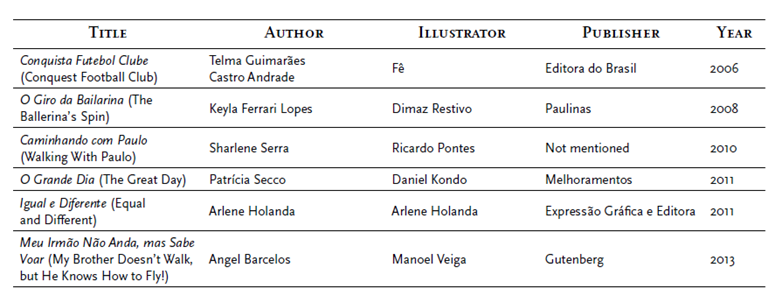

To do so, we review six books, five of which are on the NECCSO list, and only one of them is not on that list. However, regardless of their aesthetic quality, all of them were found in a children’s school library. The works were selected following only one parameter: having their first edition from 2000, produced and edited in the 21st century (Table 2).

Amongst these children’s books, the only title that plays an explicit pedagogical role is Caminhando com Paulo (2010), as the wheelchair character is the motto of a material that teaches about accessibility. In the book, a third-person narrator highlights sev eral problems faced by Paulo as a wheelchair user: sidewalks without ramps, places with stairs, cars parked in places for people with disabilities, narrow doors in movie theatres, restrooms without handrails, among others.

In this sense, there is a mismatch between the verbal and the visual text since illustrations only repeat what the text says. For example:

I was outraged by the situation of Paulo and others with reduced mobility. The next day I called a group of friends. Together we organised a mobilisation: posters, banners and speeches. We want to draw attention to the issue of accessibility in our city.

The double-page images show three wheelchair users in the foreground, one of them is Paulo, and several people holding posters and banners, with facial expressions of anger and revolt.

The narrative ends with Paulo happy, celebrating with friends since accessibility has improved in his city. Moreover, in Paulo’s words, now the subject of the speech: “this proves that together we can make changes and avoid any kind of discrimination”. The book also brings pages with activities on accessibility for readers to prove what they have learned: “walking with Paulo - an activity for students” and some articles from the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities presented in the last two pages of this book.

We perceive the role of Paulo, just as a character used to publicise the daily problems of people with physical disabilities who live in cities not planned for them. Paulo is not the protagonist, the third voice of the narrative, a poorly prepared narrator, as the reader does not know who he is but realises that he takes pity on the wheelchair user and decides to help him. There is, therefore, an explicit function in showing accessibility problems and an attempt to make the reader aware of these problems.

Regarding the criteria listed in Table 1, we could say that Paulo is a stereotyped character. However, he does not play a leadership role, and neither is he the one who solves the problem of accessibility in the city where he lives. We also believe that the story could not be narrated if the character did not have a physical disability. Although Paulo is a supporting actor, his problems with accessibility make the book Caminhando com Paulo possible.

In Igual e Diferente (2011), with illustrations and text by Arlene Holanda, the wheelchair-bound character plays a supporting role in poetic prose in which several children with differences are presented. Such differences do not stand out in the book’s opening pages by the verbal text, but by the visual, as the first girl (pp. 2-3) is dark and the second (pp. 4-5) is black. In a context of visibility, the differences in this children’s book work are marked by illustrations, which show traits of nationality, ethnicity, race, and various deficiencies: deafness, physicality, and muteness. These statements are only expressed in the verbal text from page 8 on, precisely in the middle of the book.

Clara black skin/ And curly hair/ Diego has fair skin/ And very smooth hair/ Everybody has beauty/ Each one in a particular way. Tati needs help/ So that she can walk/ João has difficulties/ To speak and listen/ They all like care / Kisses, hugs. (pp. 8-11)

The book distinguishes itself from Caminhando com Paulo for mentioning morality only on the last page: “Everyone has the right/ to health and protection/ to be able to thrive/ without any complications/ and it is good that every adult/ do not forget this lesson!” (pp. 14-15). Therefore, there is a message intended to alert adults to the rights of one’s differences. How Arlene Holanda does this in Igual e Diferente is, in the words of Kirchof et al. (2013), with a

“politically correct” bias [which] has invaded a large part of children’s literary books, especially in recent years, when the literary narratives have been taken as a vehicle to spread information, to establish moral rules and prescriptions on how to act with this or that difference. (p. 1048)

We cannot say that these two books are from children’s literature because although this presents verbal and visual processes modalities, the works analysed so far do not offer children ample possibilities to make sense of what they read, as, after all, the understandings are ready (Cadermatori, 2006).

O Giro da Bailarina (2008) tells the experience of Ana Carina, a quadriplegic girl, with ballet. The narrative is composed in the first person, the protagonist is not stereotyped, and the story does not show a problem. Ana Carina describes how she started dancing and how she likes to perform on stage with joy and a feeling of overcoming. “Hi, I am Ana Carina, and I’m ten years old. I’m here to talk a bit about what I’m feeling.

You know, I’ve just gotten off stage, I performed my first ballet presentation. It was like a dream” (pp. 1-2); “I couldn’t imagine I was able to make such slight movements that only ballerinas could. Even so, I got very happy” (p. 8).

In the book, the illustrations dialogue with the written text, expanding its meaning possibilities, since the girl subtly exposes her limitations but does not make them explicit, the reader is led by Ana Carina’s relationship with ballet to page 15, when the girl dances sitting in a wheelchair.

As it is a descriptive text in the protagonist’s voice, Ana Carina is represented as a “practitioner” character, as she is the one who dances with the teacher, the clown and her friends. There are also indications that others accept the character for her behaviour, the reader verifies that in her relationship with the teacher, “I felt like a dancer. My teacher smiled” (p. 5) and with her friends “I have other friends who, like me, also spin on wheels” (p. 20).

The characters - Ana Carina, teacher, friends - are therefore placed as positive and constructive models, and on the one hand, the protagonist and her friends, who are also wheelchair users, are happy, overcome difficulties, and the teacher accepts the differences.

In this aspect, we perceive a sense of equity, according to Cury (2005), a fundamental principle of inclusion, once the verbal text and the characters are not treated in a discriminatory way, and there is an explicit acceptance of their limitations as wheelchair users.

Likewise, in O Grande Dia (2011), by Patrícia Secco, Rodrigo is not mentioned as a person with a physical disability. The reader figures this simply by seeing the visual text on the last page. The plot is narrated by Rodrigo, a 12-year-old boy, who tells how he became the football coach for the school team.

The narrative shows the protagonist’s skill with games and strategies. Without mentioning that he has a physical disability, the reader cannot infer it through the verbal aspect only: “and as I could not run nor had anyone to play chess with, I was going to watch the football game”. The illustrations throughout the book always depict Rodrigo behind a small square one can understand is the back of a wheelchair.

The protagonist in this book is not shown to overcome his disability, as is the case with Ana Carina in The Ballerina Spin, but his perception of the problems with the football team leads him to the position of coach. The narrative presents the events sequentially, as after Rodrigo watched the game during the school break, he reports the problems to the team: “my friends were very disorganised, they looked like 11 boys playing alone - chasing the ball, each for oneself! Nothing to do with a game! Nobody passed the ball”, and he is, then, included in the group as the coach.

The character is valued for his observational skills and strategy, which places the team in the football championship final: The appreciation of teamwork and respect for people. The text ends in Rodrigo’s voice: “and how wonderful it is to know that, even without being able to run after a ball, my participation was decisive for us to be in this final!”. The image that comes with the verbal text is similar to those photographs taken at the beginning of the games when the team joins in two rows and lands for the official club photo. Thus, three boys hug and stand in front of them, two squat and Rodrigo sits in his wheelchair, holding the soccer ball.

In this aspect, Rodrigo’s inclusion in the group is different from the stories analysed in previous books. We believe that the character does not have a stereotype and that the narrative’s performance represents leadership. Therefore, Rodrigo is a practitioner character, he is the one who solves the narrative problem, and the group accepts him for his individual behaviour. He is shown as a positive role model, as his physical disability does not prevent the story from being told. Daniel Kondo’s illustrations play a significant role because, in addition to dialoguing with the verbal text, they mobilise the reader to perceive meanings that can provide an autonomous reading experience.

The theme of football is brought again in Conquista Futebol Clube (2006), by Telma Guimarães. The 32 pages book tells the story of Davi since his birth, and the paediatrician informs the boy’s parents that he was born with a malformation in the backbone. In the initial conversation between Davi’s parents and the physician, two pieces of information move the narrative: the importance of the stimulus to perform all activities; and the search for ways to carry out various tasks.

Davi’s relationship with his parents and older brother, Felipe, is seen by their coexistence, by the search for a solution to small impasses, such as a sink in the bathroom the boy’s height. It is at school that major problems will be presented: difficulty in enroll ing him in the same school as his brother because the school does not have any people with disabilities; accessibility problems and, finally, the acceptance of the disability by the other children in the classroom.

Davi’s great conflict, in the third-person narrative, is the fact that he cannot play football in physical education classes. To resolve the issue, he begins, secretly from the family, to build a wooden leg with a trainer at the end, which allows him to kick the ball. To test his invention, he needs a football team, and at this point, Davi observes other classmates and realises they don’t take part in the class either because one is obese, the other wears glasses, and so forth. The boy’s team is made up of several children who, one way or the other, felt excluded, either for being different or for bullying.

Davi then forms his team - Conquest Football Club - and the children start training on Saturdays. Felipe, his brother, plays the role of referee, and the team draws the attention of the principal and other students at the school. As an outcome, the school management prepares the school with ramps, accessible restrooms and accepts other students with disabilities; the children of the team are recognised by the other students in the school, who feel like playing soccer with them.

In Conquista Futebol Clube, the visual text has verbal text, reproducing the narrative’s events in images. For example, in the episode where Davi talks to the girl from the canteen, he suggests putting up a list of the day’s meals because he could not see the counter. The illustration on the right side of the page takes half the space vertically, and the reader can see a very tall cafeteria, with the girl at the counter and Davi with his head and arms raised, not seeing the canteen’s interior.

The protagonist and his family are not identified as stereotyped. However, the characters that appear and form the team are. Mathias, the obese boy, is called “Cork”; João, the boy with glasses, known as “Eye”; Robervaldo and Giovaneusa were excluded because of their strange names. The linguistic resources used to portray these characters’ features do not escape worn out stereotypes; however, some readers may identify with these bullying problems, all too common in schools.

Davi plays a leadership role and accepts his physical condition, looking for ways to play soccer, thus fulfilling a desire, he is accepted by the group, so there would be no possibility of telling this story without showing the boy’s disability. Therefore, other children with disabilities may find themselves in Davi, who is shown as a positive and constructive role model.

As such, the characteristics found in O Grande Dia and Conquista Futebol Clube differ from the claims made by Price et al. (2016), who state that, in exploratory research with 102 North American children’s books, characters with disabilities did not often have active roles in problem-solving nor was there a fair balance between the roles played by characters with and without disabilities.

In the last book, Meu Irmão Não Anda, mas Sabe Voar!, the first-person narrative tells the story of a girl who one day asked her mother for a little brother because she felt so lonely.

So, on my seventh birthday, I got the best gift in the world: Mom said my little brother was on his way. I found it very strange because her belly ‘wasn’t even big! How come, then, my brother was about to arrive? It was even stranger When he arrived. It ‘wasn’t a baby, it ‘wasn’t small, it was bigger than me! And ‘couldn’t walk! (pp. 9-15)

This story discusses the friendship between the girl, who has no name, and João, her brother, going through secondary experiences such as adoption and physical disability. The narrator justifies the fact that her brother cannot walk by saying, “but I found he can fly!” (p. 16). This flight has two meanings: the first, related to the speed he can give his wheelchair; and the second, an imaginary flight, described by the girl as: “he says it is at this time that he goes the farthest” (p. 18). The verbal text allows inferences about this moment as the one in which João imagines himself without the physical disability. However, there is a break in expectation on the next page when the “journey” takes the siblings to imaginary worlds of fairies, goblins and talking animals.

We could say that, although this magic remains in the boy’s “dream”, there is in the representation of this character a return to the 19th century when, according to Dowker (2013), “his creative gifts, associated to his emotional sensitivity, are more outstanding than its shortcomings” (p. 1060).

João, the narrator’s brother in Meu Irmão Não Anda, mas Sabe Voar! is not presented in a stereotyped way. He is a dynamic character, accepted by his sister, in a narrative that does not show a conflict but uses the subterfuge of the creative imagination to accept his limitations.

Final Words

The purpose of this article was to problematise the representation of characters with physical disabilities in children’s literature. We brought to the discussion, besides the theoretical assumptions the books analysed and the current legislation regarding inclusive education, also known as special.

According to the 2010 demographic census carried out by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2012), Brazil has 45,606,048 people with some type of disability, 23.90% of the population. These Brazilians are coming out of the invisibility to which they were relegated for many years and, along with family members, teachers, researchers, writers and other people committed to the cause, they are struggling so that they are not only seen and recognised as people of rights but also fighting stereotypes, stigmatisations and all forms of prejudice.

Thereupon, the issue of inclusive education and the rights of people with disabilities has been enhanced in research, legislation, and the production of children’s books in Brazil, both in literary, educational, and other works. Mainly from 2008 on, with the National Policy for Special Education in the Inclusive Perspective, bibliographic production on this subject has increased, although the issue had already arisen in some works aimed at children in previous periods. The six books analysed here date from 2006 to 2013 and present, as discussed in the previous item, different approaches towards disability.

There is no doubt that social and political pressures for inclusion interfere in literary production and its insertion in the school context. Recently, Brazil was faced with a controversy involving the minister of education, Milton Ribeiro, who stated on social media that there are children with “a degree of disability that is impossible to live with” (Alves, 2021), hindering the learning of others students. His statement was the target of much criticism from all segments of society, which made Milton Ribeiro back down and apologise to the population. This fact highlights the lack of information of many Brazilians about disability and inclusion. That would be one more reason for publishers to produce children’s books on the subject and, along with parents and teachers, to develop information and clarification campaigns so that children’s literature with characters with disabilities may be in the classrooms and discussed among school managers, students and teachers.

Hence, it is relevant to analyse works that neither reinforce stereotypes placing the characters in conditions of subordination and/or inspiring pity, nor refer to disability as heroic overcoming, resignation and acceptance of destiny or divine will. Therefore, by problematising the representation of characters with physical disabilities in texts aimed at the infant reader, we hope to have contributed to the expansion of perspectives on what is stigmatised as disability and the limits and possibilities of human beings in different conditions and potentialities

Referências

Adomat, D. S. (2014). Exploring issues of disability in children’s literature discussions. Disability Studies Quarterly, 34(3), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v34i3.3865 [ Links ]

Altieri, J. L. (2008). Fictional characters with dyslexia: What are we seeing in books? Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 41(1), 48-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990804100106 [ Links ]

Alves, P. (2021, 19 de agosto). Ministro da Educação diz que a crianças com grau de deficiência que ‘é impossível a convivência’. Globo. https://g1.globo.com/pe/pernambuco/noticia/2021/08/19/ministro-da-educacao-criancas-impossivel-convivencia.ghtml [ Links ]

Barros, A. S. (2015). Quarenta anos retratando a deficiência: Enquadres e enfoques da literatura infantojuvenil brasileira. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 20(60), 167-193. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782015206009 [ Links ]

Beckett, A., Ellison, N., Barrett, S., & Shah, S. (2010). ‘Away with the fairies?’ Disability within primary-age children’s literature. Disability & Society, 25(3), 373-386. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687591003701355 [ Links ]

Cadermatori, L. (2006). O que é literatura infantil. Brasiliense. [ Links ]

Coelho, N. N. (2000). Literatura infantil: Teoria, análise, didática. Moderna. [ Links ]

Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. art. 205. [ Links ]

Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. art. 208, §III. [ Links ]

Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. art. 206, §I. [ Links ]

Curwood, J. S. (2013). Redefining normal: A critical analysis of (dis)ability in young adult literature. Children’s Literature in Education: An International Quarterly, 44(1), 15-28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-012-9177-0 [ Links ]

Cury, C. R. J. (2005). Os fora de série na escola. Armazém do Ipê. [ Links ]

Decreto Legislativo nº 186, de 2008 (2008). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Congresso/DLG/DLG-186-2008.htm [ Links ]

Decreto nº 6.571, de 17 de setembro de 2008 (2008). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2008/decreto/d6571.htm [ Links ]

Decreto nº 3.298, de 20 de dezembro de 1999 (1999). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/d3298.htm [ Links ]

Dowker, A. (2013). A representação da deficiência em livros infantis: Séculos XIX e XX. Educação & Realidade, 38(4), 1053-1068. [ Links ]

Dyches, T. T., & Prater, M. A. (2005). Characterization of developmental disabilities in children’s fiction. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 40(3), 202-216. [ Links ]

Emenda Constitucional nº 65, de 13 de Julho de 2010 (2010). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Constituicao/Emendas/Emc/emc65.htm [ Links ]

Flynn, K. S. (2001). Developing children’s oral language skills through dialogic reading: Guidelines for implementation. Teaching Exceptional Children, 44(2), 8-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005991104400201 [ Links ]

Freire, S. (2008). Um olhar sobre a inclusão. Revista da Educação, 16(1), 5-20. http://hdl.handle.net/10451/5299 [ Links ]

Hughes, C. (2012). Seeing blindness in children’s picturebooks. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 6(1), 35-51. [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2012). Censo brasileiro de 2010. IBGE [ Links ]

Kirchof, E. R., Bonin, I. T., & Silveira, R. M. H. (2013). Apresentação - Literatura infantil e diferenças. Educação & Realidade, 38(4), 1045-1052. https://doi.org/10.1590/S2175-62362013000400002 [ Links ]

Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996 (1996). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9394.htm [ Links ]

Lei nº 13.146, de 6 de julho de 2015 (2015). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2015/lei/l13146.htm [ Links ]

Lei nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014 (2014). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/lei/l13005.htm [ Links ]

Machado, M. Z. V. (2014). Gêneros literários para crianças. In I. C. Frade, M. G. C. Val , & M. Bregunci (Eds.), Glossário Ceale de termos de alfabetização, leitura e escrita para educadores. CEALE, Faculdade de Educação da UFMG. [ Links ]

Paiva A. (2008). A produção literária para crianças: Onipresença e ausência das temáticas. In A. Paiva, & M. Soares (Eds.), Literatura infantil: Políticas e concepções (pp. 35-52). Autêntica. [ Links ]

Pimentel, F. (1952). Histórias da avozinha. Livraria Quaresma. [ Links ]

Portaria nº 1.793, de dezembro de 1994 (1994). http://portal.mec.gov.br/seesp/arquivos/pdf/port1793.pdf [ Links ]

Prater, M. A. (1999). Characterization of mental retardation in children’s and adolescent literature. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 34(4), 418-431. [ Links ]

Price, C. L., Ostrosky, M. M., & Mouzourou, C. (2016). Exploring representation of characters with disabilities in library books. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44(6), 563-572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0740-3 [ Links ]

Quicke, J. B. (1985). Disability in modern children’s fiction. Croom Helm. [ Links ]

Resolução CNE/CEB nº 2, de 11 de setembro de 2001 (2001). http://portal.mec.gov.br/cne/arquivos/pdf/CEB0201.pdf [ Links ]

Sipe, L. R. (2012). Revisiting the relationships between text and pictures. Children’s Literature in Education, 43, 4-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-011-9153-0 [ Links ]

Sonnenschein, S., & Munsterman, K. (2002). The influence of homebased reading interactions on 5-year- olds’ reading motivations and early literacy development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 17(3), 318-337. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2006(02)00167-9 [ Links ]

Souza, R. J., & Bortolanza, A. M. E. (2012). Leitura e literatura para crianças de 6 meses a 5 anos: livros, poesias e outras ideias. In R. J. Souza , & E. A. Lima (Eds.), Leitura e cidadania (pp. 67-90). Mercado de Letras. [ Links ]

Wopperer, E. (2011). Inclusive literature in the library and the classroom: The importance of young adult and children’s books that portray characters with disabilities. Knowledge Quest, 39(3), 26-34. [ Links ]

Yenika-Agbaw, V. S. (2011). Reading disability in children’s literature: Hans Christian Andersen’s tales. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 5(1), 91-107. [ Links ]

Zilberman, R., & Lajolo, M. (1993). Um Brasil para crianças - Para conhecer a literatura infantil brasileira: história, autores e textos. Global. [ Links ]

Received: June 16, 2021; Accepted: October 04, 2021

texto em

texto em