Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Comunicação e Sociedade

versão impressa ISSN 1645-2089versão On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.45 Braga jun. 2024 Epub 30-Jun-2024

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.45(2024).4754

Varia

Journalistic Quality and Democratic Stability in Times of Crisis: Empirical Reflections from Spanish Newspapers

1 Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Alcalá, Alcalá de Henares, Spain

No contexto social e político em que vivemos, com um incremento de atores sociais neopopulistas e um cenário de instabilidade democrática, é fundamental entender a qualidade do jornalismo na pós-democracia. A situação de infodemia, que vivemos durante a pandemia da COVID-19, ressaltou os aspetos negativos do uso das redes sociais como ferramenta de informação que ajuda a desenvolver as competências básicas para exercer uma cidadania ativa na democracia liberal. Nestas circunstâncias, é fundamental analisar o papel do jornalismo de referência no combate à desinformação e a sua importância no fomento do pensamento crítico da cidadania, para, desse modo, inserir na agenda pública temas de interesse público.

O objetivo principal desta investigação é analisar a qualidade do conteúdo produzido por jornais espanhóis de referência e disponibilizado aos cidadãos por meio das redes sociais. Para isso, utilizamos como metodologia os paradigmas qualitativo e quantitativo, centrados no quadro epistemológico em que estão circunscritos, para realizar uma análise ao conteúdo, a sua tendência e viés político relativamente aos boatos sobre o coronavírus publicados pelos jornais de referência no cenário nacional e regional nos seus perfis do Facebook.

Os resultados desta investigação revelam uma baixa interação da audiência com as publicações e abrem novas discussões sobre o tipo de matérias que atraem a atenção do público e que, ao mesmo tempo, podem cumprir com a formação e o fomento do pensamento crítico da cidadania.

Palavras-chave: qualidade jornalística; cidadania; democracia; jornais espanhóis pós-democracia

In today’s social and political landscape, marked by the rise of neopopulist social players and heightened democratic uncertainty, it becomes imperative to understand the quality of journalism in post-democratic frameworks. The infodemic witnessed amidst the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the pitfalls of relying on social media as a primary information source able to facilitate the development of fundamental skills necessary for active citizenship within liberal democracies. Given these circumstances, it is essential to analyse the pivotal role of mainstream journalism in countering disinformation and fostering critical thinking among citizens, thereby elevating public interest concerns onto the societal agenda.

The primary objective of this research is to assess the quality of the content produced by prominent Spanish newspapers and disseminated to the public via social media. Employing both qualitative and quantitative paradigms as a methodology within the epistemological framework that guides them, we analyse the content’s tendencies and political biases concerning rumours about the coronavirus published by leading national and regional newspapers on their Facebook profiles.

The findings of this investigation indicate minimal audience engagement with the posts, prompting further discussions on the kinds of stories that capture public interest while also nurturing critical thinking skills among citizens.

Keywords: journalistic quality; citizenship; democracy; post-democracy Spanish newspapers

1. Introduction

Technological progress in communication and information has contributed to a global landscape that exacerbates democratic crises, characterised by the proliferation of neopopulist political figures, widespread use of post-truth narratives, and the pervasive influence of digital social media platforms on the public discourse. This phenomenon, often termed “post-democracy”, has implications across various regions, including Latin American countries, the Arab world, Europe and the United States. For Ballestrin (2017), key features of post-democratic societies include unstable political-institutional environments and the emergence and participation of new players espousing anti-democratic rhetoric on the public stage. In this context, mainstream journalism assumes a critical role as a vital institution for upholding democratic principles and safeguarding human rights.

Some researchers in the field of communication regard the media as a cornerstone of society, as they play a pivotal role in shaping public discourse and constructing the narratives that define our realities. The concept of “counter-power” inherent in public action serves as a safeguard for democracy within the framework of freedoms and values upheld in Western societies (Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2016).

According to Picard (2004), quality journalism is an essential and highly influential element in addressing cultural, social, and political issues within democratic States. Schulz (2000) further underscores the importance of independence, objectivity, diversity of content, and accessibility in the provision of quality information, thereby reinforcing democratic values. In light of these concepts, it becomes imperative to engage in discussions regarding the quality of journalism as a means of safeguarding liberal democracies.

Prominent theorists of contemporary representative liberal democracy, including Giovanni Sartori and Robert Dahl, highlight the indispensable role of the press in both exercising and consolidating democracy. Dahl (2006) posits that citizens in liberal and representative democratic societies require civic competence - a condition cultivated through the unrestricted dissemination of information, which will facilitate the formation of an autonomous and independent public opinion.

However, access to different communication tools has changed the role of leading newspapers since citizens have various platforms to stay informed. In Spain, 44% of readers rely on social network algorithms and search engines to access news, whereas direct access to traditional media accounts for 39% (Amoedo et al., 2020). This shift may have implications for the democratic State (Feenstra et al., 2016).

This passive access to information fosters what Pariser (2011) termed a “filter bubble”, where internet users receive information tailored to their predictions, collected by algorithms analysing their search history and social network interactions. Within this framework, internet users can easily disregard information conflicting with their preestablished opinions, leading to the formation of ideological and cultural bubbles, effectively isolating themselves.

Nonetheless, during times of crisis, such dynamics can shift. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a notable surge in information-seeking behaviour from the press, with Spanish citizens predominantly turning to digital versions of leading newspapers (83%) and television (71%) for updates. Social media ranked third in popularity (63%). Particularly during the April 2020 lockdown prompted by the public health emergency, the primary sources of information were the media (74%), followed by the national Government (39%), scientists, doctors, and specialists (39%), and global health organisations (33%; Kleis-Nielsen et al., 2020).

Beyond academic debates regarding the influence of social media on citizenship, amid theories from both “cyber-optimists” and “cyber-sceptics”, society is undergoing a profound technological revolution, accentuating the need for fostering critical thinking. Consequently, the role of quality mainstream journalism becomes increasingly crucial for democratic stability. As noted by McQuail (2013), while rooted in practicality rather than philosophical or normative underpinnings, the expectation for media to provide quality information stands on par with fundamental principles such as equality, freedom, and diversity.

2. State of the Art

News stories highlighting the perceived threat to democracy have become increasingly prevalent in the Spanish press, with headlines such as: “La Democracia Amenazada” (Democracy Threatened) - El País; “Cómo Internet Se Convirtió en una Amenaza Para la Democracia” (How the Internet Became a Threat to Democracy) - El Mundo; “Las Fake News, una Amenaza Para la Democracia” (Fake News, a Threat to Democracy) - La Vanguardia; “El Futuro de la Democracia Española: Cara o Cruz” (The Future of Spanish Democracy: Heads or Tails) - La Voz de Galicia.

However, the Democracy Index 2019 - A Year of Democratic Setbacks and Popular Protest, conducted by The Economist Intelligence Unit (2019), identifies Spain as one of the 22 countries classified as enjoying a fully democratic State. This assessment is based on indices achieved in five categories: “electoral process and pluralism”, “functioning of Government”, “political participation”, “political culture”, and “civil liberties”.

If the country is classified as one of the best democracies in the world, what accounts for the headlines about the threat to the democratic system? The factors contributing to Spain’s ranking as 17th out of 22 countries enjoying full democracy may offer some insights into this situation. These factors suggest areas where the country can improve both the functioning of its Government and the political participation of its citizens.

Adam Przeworski’s (2019) examination of the fundamentals of democracy, as outlined in the book Crises of Democracy, sheds light on this context. According to Przeworski, threats to democracy are not solely political but also deeply rooted in economic and social spheres. The author emphasises that polarisation, exacerbated by neo-populism, poses significant challenges to the health of democracy.

2.1. A Brief Analysis of the Threats to Democracy

In order to understand the correlation between polarisation and the growing emergence of political leaders with totalitarian profiles and democratic stability, it is crucial to delve into the concepts expounded by the German philosopher Hannah Arendt. Arendt advocates for the establishment of democratic political arenas as spaces for the free expression of opinions and the challenging of established truths, thereby facilitating dissent and consensus through strategies of persuasion and dissuasion. In her work, As Origens do Totalitarismo (The Origins of Totalitarianism), Arendt (1951/1989) emphasises that “the ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction no longer exist” (p. 312).

According to Arendt (2003), cinema and radio played crucial roles in facilitating the spread of totalitarianism during the first half of the 20th century. Although dictators also resorted to violence to suppress truths that resisted manipulation, the German philosopher underscores the power of communication and emphasises the need for a free and responsible press to uphold the democratic system. At this point, it is noteworthy that our super-connected lifestyle has exponentially amplified the possibilities for manipulation.

For the philosopher Óscar Barroso Fernández (2020), we live in a world where the obliteration of truth no longer requires silencing witnesses but rather drowning their voices amid a sea of lies or hoaxes. The author argues that we are trapped in a “perverse dynamic based on lies, where under the guise of a false freedom of expression, uncomfortable factual truths are distorted into opinions with which one may or may not agree” (Barroso Fernández, 2020, para. 6).

Drawing from the concepts of Arendt (1967), who contends that “freedom of opinion is a farce unless factual information is guaranteed and if the facts themselves are not in dispute” (p. 49), one can appreciate the pivotal role of quality journalism in combatting disinformation and threats to democracy.

2.2. Public Trust in Democratic Institutions

In democratic societies, journalism can be seen as a key element in the articulation of the public sphere (Habermas, 2006), serving as a mediator between the State and society, ensuring the population access to information of public interest. As Casero-Ripollés (2020) points out, access to information impacts not only citizens’ understanding of their immediate reality and their commitment to public affairs but also the very concept of “democracy”, given the intimate connection between information and the democratic State.

As a dynamic and adaptable concept, democracy changes as the social, cultural and political frameworks of society evolve. Within this evolutionary paradigm, the media and citizen participation are the driving forces behind this development. For Dahl (2006), in a country where the right to vote exists but where its rulers repress the opposition, representation and participation, essential axes in democratic societies, may suffer. Hence, the significance of one of journalism’s primary objectives: provide citizens with socially pertinent information, enabling them to form opinions on the subject and fostering civic competencies for social and political participation (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2007).

The concept of “democratic citizenship”, established by Hannah Arendt (2005/2008), posits that citizens should have a civic competency nurtured by a free and equal public space. A place that gives them a voice and allows them to develop a political culture grounded on dialogue aimed at forging agreements and peacefully resolving conflicts in the public arena. Instilling these attributes of civility demands dedication and engagement from citizens alongside transparent and trustworthy public institutions.

According to the report La Calidad de las Instituciones en España (The Quality of Institutions in Spain; Lapuente et al., 2018), the trust population’ demonstrates in the administrations that provide public services is remarkable, in contrast, the trust rate in the political system is the lowest in Europe. Only 13% of individuals express trust in politicians, while 20% express trust in political parties. Alberola (2018) states that in “Spain, political scandals have eroded citizens’ trust in public institutions and their satisfaction with the functioning of democracy” (para. 2).

The lack of trust in politicians among the Spanish people has been particularly evident during the COVID-19 crisis. In a survey conducted in the country, only 31% of respondents expressed belief in the information about the coronavirus provided by politicians, and 45% believed the information provided by the Government (Kleis-Nielsen et al., 2020).

Distrust of public institutions and politicians is also evident in the data on fake news. A survey of internet users indicates that 49% of Spanish people identify the Government, politicians and national parties as the primary sources of disinformation, followed by journalists (15%), citizens (11%) and other political actors or foreign activists groups (8%; Amoedo et al., 2020).

During crises such as that generated by the coronavirus pandemic, it becomes imperative for governments to demonstrate transparency and trustworthiness to garner citizen support and participation in addressing the social emergency. In this scenario, the press plays a crucial role in explaining to the public unfolding events and engaging them in finding solutions, serving as a vital ally in the political, institutional, and health management efforts of governments (Costa-Sánchez & López-García, 2020).

2.3. The Concept of “Quality in Journalism”

As a starting point, we have relied on international studies highlighting the absence of a universally accepted concept defining quality journalism, even though there is a consensus on the existence of fundamental criteria for this practice. Primary research on this topic predominantly centres on academic analyses and the perspectives of professionals to delineate categories indicative of “quality journalism”, often associated with the designation of “leading newspapers”.

Researchers such as Shapiro et al. (2006) suggest that current literature has assessed quality in journalism by employing criteria rooted in values such as accuracy, impartiality, the reputation of the news organisation, sources of information and the content of the reported stories. Lacy and Rosenstiel (2015) propose that while each individual may have their interpretation of quality in journalism, it likely aligns with that of a collective group sharing common experiences.

Most recent studies examine quality from either the demand or production perspective. In the demand approach, emphasis is placed on the interaction between citizens’ needs and the news content. On the other hand, the methodology that analyses production focuses on the characteristics of the content (Lacy & Rosenstiel, 2015). Drawing from the concepts advocated by the researchers above, it is possible to infer that in the content-focused approach, the public assesses the news based on their own standards, thereby determining whether it meets quality criteria or not. McQuail (2011/2012) suggests that quality measured through demand is tied to how journalism is perceived in fulfilling the needs and desires of citizens, adopting a relativistic approach that may reinforce arguments suggesting that quality cannot be objectively measured due to its inherent subjectivity.

A study conducted by McQuail (2013) highlights some fundamental requirements for the quality of information, including comprehensive coverage of relevant news and general information concerning local and international events; objective, factual, accurate, reliable information that aligns with reality; balanced and fair information, reporting alternative perspectives and interpretations soberly and impartially.

According to Vehkoo (2010), there are no universal criteria to ascertain the quality of journalism, as it is contingent upon factors such as socioeconomic and educational contexts. Nevertheless, in light of the standards and codes of conduct shared by professionals globally, the researcher affirms the notion that a well-functioning democracy requires an informed public.

Theoretical discussions generally indicate that journalistic quality can be directly influenced by the social and cultural background of the community surrounding its production, thereby emphasising the importance of observing its context within the specific space-time continuum (Santos & Guazina, 2019).

2.4. Consumption of Mainstream Newspapers Today

In recent years, there has been a decline in readership and credibility for mainstream newspapers, jeopardising their social relevance (Carlson, 2017). Moreover, they now compete for the limelight with other social players (Casero-Ripollés, 2020). However, the coronavirus outbreak has underscored the importance of traditional media during crisis. In April 2020, 56% of Spanish people acknowledged that the media had helped them understand the pandemic. Meanwhile, 64% stated that traditional media explained the measures they could take in response to the coronavirus (Negredo, 2020).

The heightened interest in news stemming from the coronavirus pandemic has resulted in a surge in the volume of reports on the topic. Lázaro-Rodríguez and HerreraViedma (2020) note that the number of news articles published in online newspapers in Spain rose by nearly 50% in the first 30 days following the implementation of mobility restrictions in March 2020.

While the use of social media to access information is growing (Newman et al., 2019), it is important to acknowledge their limitations in order to generate a well-informed and civically engaged citizenry (Zúñiga et al., 2017). Apart from fostering the “filter bubble” phenomenon, the possibility of consulting multiple digital platforms promotes an environment impregnated with information, potentially leading to confusion regarding the factuality of each one. This saturated environment contributes to the proliferation of misinformation (Bennett & Livingston, 2018) and reduces trust in traditional media while encouraging political polarisation (Van Aelst et al., 2017).

Despite the surge in the consumption of mainstream newspapers during the coronavirus pandemic, there is a prevailing trend of low trust in the press. Only 36% of Spanish internet users report regular trust in the news. This marks the lowest level of news credibility since 2015, reflecting political and social events that polarise citizens (Amoedo et al., 2020). Data from a survey conducted in Spain in 2020 reveals that 48% of respondents favour obtaining information from impartial sources, while 30% opt for media aligned with their ideologies, and 10% declare following channels that offer diverse viewpoints. Among readers at the opposite ends of the political spectrum (both left and right), more than 40% express a preference for media outlets that echo their perspectives (Amoedo et al., 2020).

A survey conducted by the Reuters Institute (Kleis-Nielsen et al., 2020) discloses additional significant findings: 60% of users who seek information in mainstream newspapers (online or offline) state they value the social function of journalism. However, among those who rely on social media to stay informed, this figure drops to 45%. In light of these insights, media organisations are compelled to invest in economically sustainable business models that allow them to fulfil their social role while concurrently rebuilding trust among citizens.

2.5. Social Media and Disinformation

Theorists such as Loader and Mercea (2012) underline that, despite its potential, the use of the internet is not always as positive as it should be. As an example of the negative use of technology, we can cite the avalanche of disinformation caused by the spread of rumours on social media, which can lead to political and social instability, posing a threat to democracy. In the political sphere, we experienced the spread of fake news in the Brexit vote (2016), the United States presidential elections (2016) and the Brazilian presidential elections (2018). Furthermore, in the realm of health, the zika virus outbreak in 2015 is an example of disinformation, as is the coronavirus pandemic.

Social media facilitate a significant flow of information, where it is possible to find genuine news, written and verified through basic journalistic techniques, and navigate between rumours and biased information imbued with ideological messages, each presenting truth from particular perspectives (Wood, 2018). Specifically concerning the coronavirus pandemic, the dissemination of news was so widespread that the World Health Organization (2020) declared the situation as an “infodemic”, indicating an overwhelming abundance of information that made it difficult to identify reliable sources and accurate guidelines.

As the disease progressed globally, misinformation also spread rapidly, despite the efforts of platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp and Google to mitigate its dissemination. Likewise, many social network users took to flagging suspicious content, contributing to the fight against misinformation (Pérez-Dasilva et al., 2020). During the first two months of the pandemic, the Spanish fact-checking organisation Maldita.es verified and debunked 586 rumours about COVID-19.

According to a report by Blanco (2020) in the newspaper El País, the National Police attended to more than 7,000 individuals in a single day who expressed doubts regarding the accuracy of messages received on social media. Such a high level of misinformation is particularly concerning given the context of a public health crisis. In these situations, it is not enough for people to be well-informed; it is imperative that they also cooperate to mitigate the spread of the disease.

The proliferation of fake news increases distrust in institutions, leading to social instability and instilling confusion and anxiety among the population (Waisbord, 2018). This impacts governments and politicians, as disinformation has the potential to sway the beliefs of even those who are supportive of the ruling administration (Casero-Ripollés, 2020), fostering an environment that is detrimental to democracy. According to several studies, the profusion of rumours is fuelled by the availability of diverse alternative sources of information. It is often linked to populism and radicalism, which exploit this strategy to garner support (Bennett & Livingston, 2018).

The “infodemic” resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic has unveiled paradoxical scenarios wherein social players tasked with combating the spread of fake news have become purveyors of disinformation. Examples include a Chinese Government spokesperson disseminating the rumour that the virus originated from the United States, a claim echoed by Chinese State media. Russian media suggested that COVID-19 was engineered in a laboratory in Georgia, United States of America. Additionally, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro speculated that the virus could be a potential biological weapon targeting China while also promoting natural remedies to cure the virus in a tweet that was flagged on Twitter (Pérez-Dasilva et al., 2020).

2.6. Combating Disinformation

The combat against disinformation and its repercussions on democratic societies involves various approaches, with different disciplines playing a role in alleviating the situation. In the book The People Vs Tech, author and journalist Jamie Bartlett (2018) argues that governments should establish effective regulations for social media, targeting oligopolies, and exercising oversight over algorithms.

Online search platforms, instant messaging companies, and certain social media are also actively engaged in developing tools to curb the dissemination of false information. Google has forged partnerships with verification firms and is enhancing its algorithm-based filtering system for search results. In response to the coronavirus “infodemic”, WhatsApp has implemented a new measure to restrict the frequency with which messages can be forwarded. Facebook has started sending pop-up notifications to users who have interacted with questionable content related to the coronavirus (García, 2020).

In fulfilling their social role as contributors to the consolidation of democracy, news organisations are tasked with implementing measures to counter the proliferation of misinformation, including the use of verification tools and heightened vigilance in verifying news accuracy (González-Fernández-Villavicencio, 2014). Meanwhile, the primary challenge lies in recovering and consolidating public trust by delivering high-quality content. Most Spanish internet users (64%) perceive that the media effectively disseminates timely information, but only half (56%) believe that leading newspapers provide in-depth analysis and insight (Newman et al., 2019, p. 24).

In an effort to restore the industry’s credibility and establish standards of trust, an international media consortium, The Trust Project(https://thetrustproject.org/), collaborates with technology platforms to reaffirm journalism’s commitment to transparency, accuracy, inclusion and fairness, thereby empowering readers to make informed decisions. The project involves the participation of 121 media outlets worldwide, including prominent names such as The Economist, The Washington Post, La Repubblica, Corriere Della Sera, Deutsche Presse-Agentur, as well as Spanish newspapers El País and El Mundo. Additionally, search engines and various social media are engaged in the project as external partners, as they have become important distributors of news.

The Trust Project’s guiding principles stem from those developed in 1947 by the Hutchins Commission, spelling out the commitments a free and responsible press must follow. In order to establish trust indicators, they are committed to:

fairness and accuracy: publishing corrections or clarifications as promptly as possible

disclosures that explain their mission, source(s) of funding and the organisation behind them

insight into their methods and where they get their information

a diversity of voices and perspectives

opportunities for public engagement

Combating disinformation also relies on fact-checking platforms, which are dedicated to identifying false information and disseminating accurate data. In Spain, the most prominent companies in this field are Maldita.es, B de Bulo and Newtral. Their objective is to equip citizens with the tools to discern between fake news and legitimate news. To achieve this, they monitor political discourse and information circulating on social media, analysing messages using data journalism techniques. Additionally, they encourage citizen participation by soliciting verification of suspicious content via WhatsApp, thereby providing a valuable service to the public (Palomo & Sedano, 2018).

3. Methodology

Given the pivotal role of journalism in countering disinformation and its consequential impact on democratic stability (Casero-Ripollés, 2020), coupled with the significance of the social network Facebook in citizens’ information access (Amoedo et al., 2020), this study aims to assess the quality of content provided to citizens. The focus is on production, examining the publishing trends of leading national and regional newspapers on their Facebook profiles regarding rumours about the coronavirus. Accordingly, the study seeks to address the following questions (Q):

Q1: does the ideological bias of newspapers influence their treatment of fake news related to the coronavirus?

Q2: does the content of coronavirus rumours follow a consistent pattern?

Q3: does the content generate interactivity with the public?

To address these questions, we propose hypotheses (H) aligned with the theoretical framework underpinning this study:

H1: the ideological bias of mainstream newspapers can influence the perception of publication quality from the production approach, where diversity, plurality of opinions and impartiality should be paramount.

The research conducted to address the presented hypothesis was grounded in both qualitative and quantitative paradigms within the encompassing epistemological framework (Arellano, 2013). This study involved an analysis of the content, emphasising its trends and political biases, specifically concerning rumours about the coronavirus disseminated by prominent newspapers across the national and regional scene on their Facebook profiles.

To meet the objectives, we opted to examine the social network content of five Spanish newspapers spanning the period from January 30 to April 30, 2020. Specifically, our focus was on analysing posts on Facebook, given its status as the most used social network by the Spanish people for general information, particularly regarding the coronavirus (Kleis-Nielsen et al., 2020).

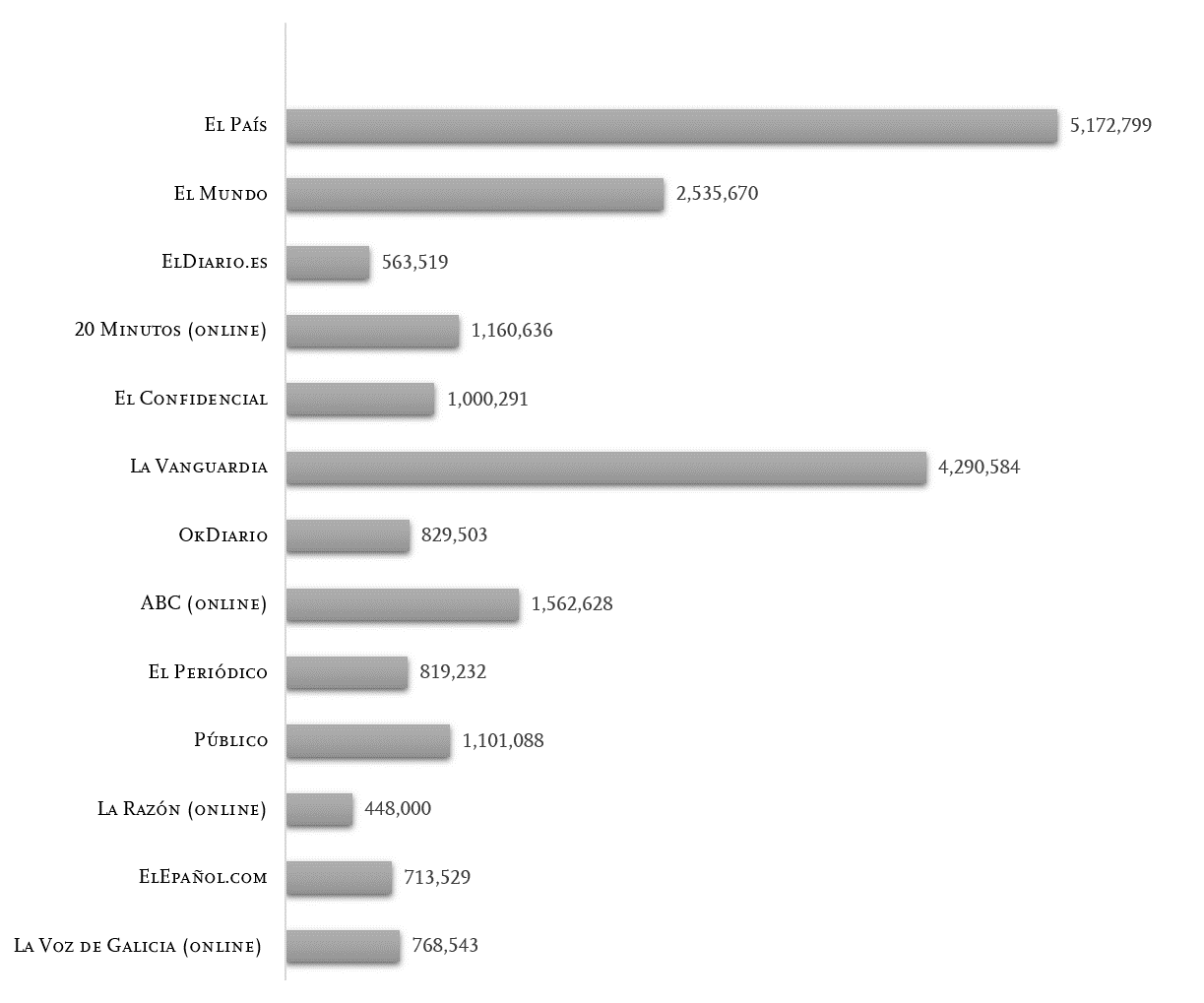

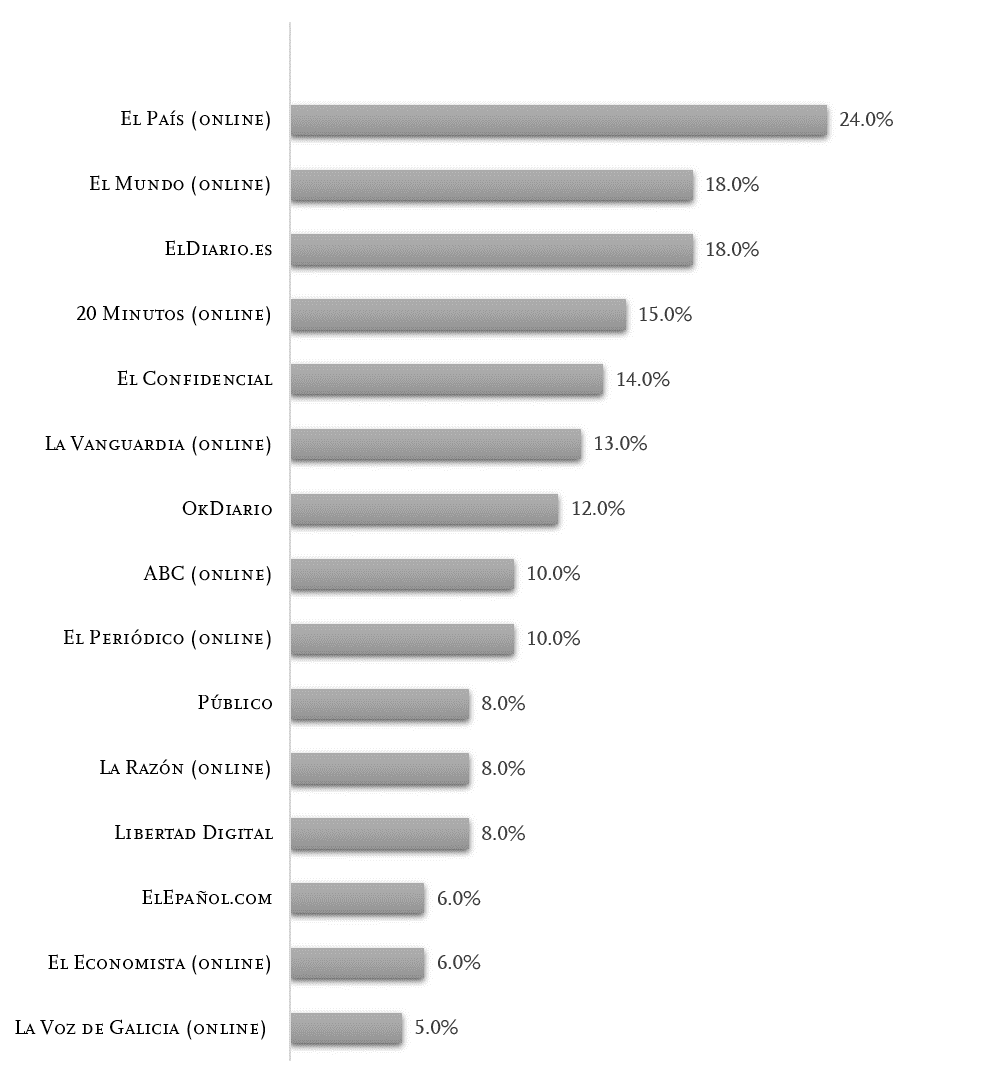

National and regional newspapers were selected based on a correlation between their online audience leadership, the number of Facebook followers, and the ideological orientation of the media. Figure 1 illustrates the leading online newspapers in Spain, while Figure 2 shows the number of fans/followers on the Facebook profiles of these newspapers.

Figure 1 Leading Spanish newspapers in terms of audience (online versions of traditional newspapers and digital natives)

Based on this data, the following newspapers were selected: El País, La Vanguardia, El Mundo, El Periódico and La Voz de Galicia. In order to analyse the data compiled, an ad hoc form (Fontecoba et al., 2020), gathering the main characteristics of the publications relevant to the study was used.

To analyse user interaction with the posts, we employed the theory of uses and gratifications as a framework, which delineates the disparity between clicks and comments on posts. Clicks are often associated with entertainment, whereas comments are more prevalent in content that elicits citizen participation in issues of public interest (Bengoa et al., 2020).

The posts were analysed using the search engine available on each of the Facebook profiles under study, employing two sets of keywords. The first set (“sars-cov-2”, “covid-19”, “coronavirus”, “pandemic”, and “state of emergency”) was used to identify the number of posts on the topic, while the second set (“rumours”, “fake news”, “misinformation”, and “fact-checking”) was employed to scrutinise the content. It is important to note that the search engine does not differentiate between uppercase and lowercase letters. Results were obtained for each newspaper from the data extracted from the posts, and comparative conclusions were drawn among them.

4. Findings

In the quantitative analysis of posts spanning from January 30, 2020 (the date of the World Health Organization’s declaration of the coronavirus as an international public health emergency) to April 30 (the period when the lockdown relaxation began, allowing children to go out on the streets), a total of 395 posts were identified regarding the coronavirus, while 112 posts focused on fake news about the virus. Specifically, between January 30 and February 4, 2020, only six news pieces related to COVID-19 rumours were published across all the newspapers under study. However, following the declaration of a state of emergency on March 14, the number of posts on this topic surged by 85%.

The number of posts identified through the Facebook search engine shows a consistent average across the five newspapers analysed, but there are differences in the topics covered. Regarding independence, objectivity, diversity of content, and accessibility, it was evident that national newspapers dedicated more attention to posts with a political or ideological bias compared to regional newspapers. Conversely, regional newspapers posted fewer updates about guidelines, prevention measures for contagion, or messages aimed at reassuring the population. Posts with a political or ideological slant were further categorised into three sub-themes, with only the Catalan newspapers featuring news pertaining to regional-specific issues such as fraud.

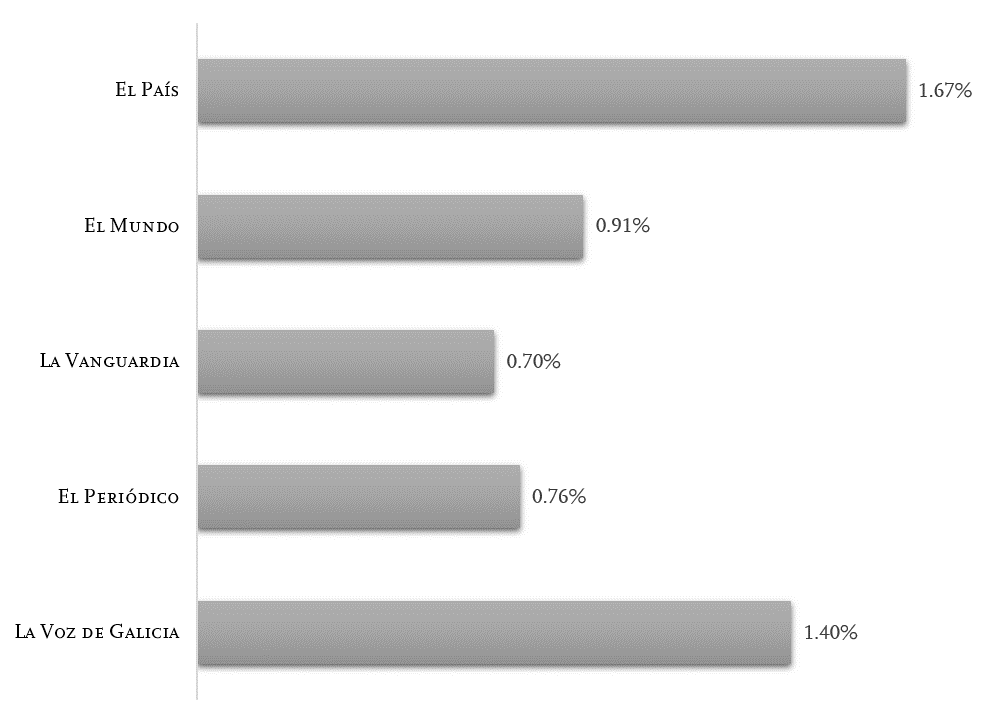

Overall, the qualitative analysis of the content indicates minimal audience interaction with the posts, with an engagement rate of less than 0.58% - a percentage deemed satisfactory by the advertising industry. Nonetheless, each newspaper achieved at least two posts with engagement rates surpassing this threshold. El País had the highest rate at 1.67%, closely followed by La Voz de Galicia at 1.40%. Conversely, the other newspapers failed to reach the 1% mark, as illustrated in Figure 3.

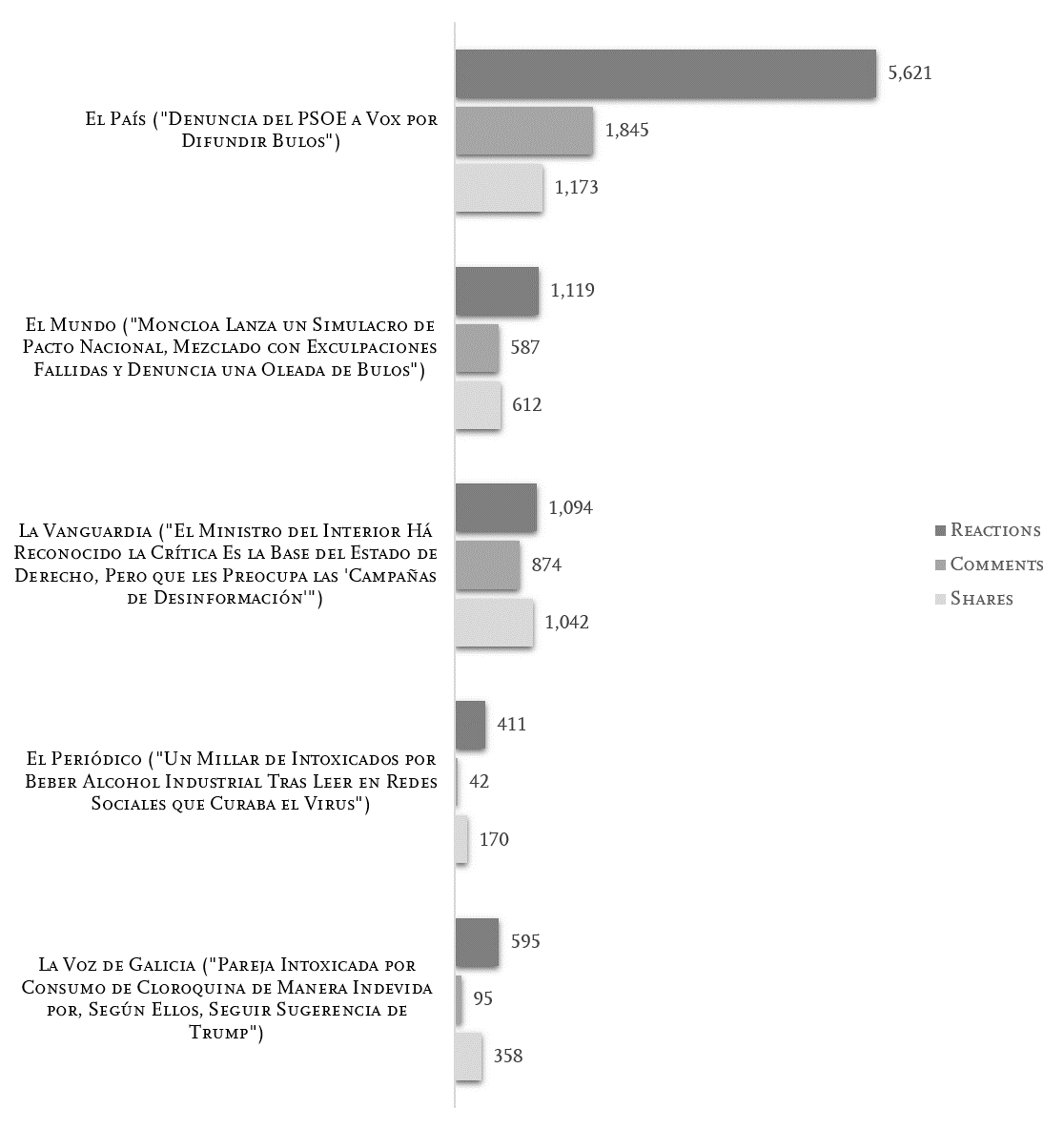

Regarding accuracy and impartiality, the posts that garnered the highest interaction rates from readers (reactions, comments, and shares) are primarily associated with content featuring a political or ideological bias across most of the newspapers analysed, except for El Periódico, which achieved significant reader engagement with a post discussing Iranians intoxicated by industrial alcohol after reading on social media that it cured the virus, as depicted in Figure 4.

As previously explored in this study, certain fundamental criteria contribute to the quality of information, including comprehensive coverage of relevant news and general information concerning local and international events; objective, factual, accurate, and reliable information consistent with reality; and the presentation of balanced and fair perspectives. Despite the paramount importance of “impartiality” in journalistic quality, news concerning the pandemic’s political or ideological dimensions garnered the highest levels of audience engagement across all five newspapers analysed, except for El Periódico, which achieved its peak interaction through a video debunking coronavirusrelated myths. Moreover, we observed varying approaches to the same news topic across newspapers with different ideological orientations. For instance, the coverage of the Attorney General’s Office investigation into the propagation of coronavirus rumours was portrayed differently by El País and El Mundo.

Concerning the textual content, it was observed that there is no consistent writing pattern among the newspapers examined. Typically, national newspapers feature more comprehensive and explanatory texts. Conversely, regional media tend to be more concise in their publications, particularly the Catalan newspaper El Periódico.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our study reveals that newspapers aligned with the Government tend to emphasise the opposition’s potential errors in disseminating rumours. In contrast, outlets more aligned with the opposition tend to highlight the Government’s potential missteps in crisis management. These tendencies hinder an objective analysis of content quality from a production standpoint, as proposed in this research. Additionally, we observed that the writing style of news related to fake news about COVID-19 lacks a consistent pattern that would facilitate immediate identification of such publications by the audience.

Following the demand approach, which establishes the quality of journalism based on audience interaction, our findings suggest that despite the public interest in the topic, the publications often failed to capture sufficient attention to generate significant interaction. However, it would be inaccurate to conclude that citizens lack interest in the news altogether; rather, our study indicates a lack of engagement with the specific publications analysed here.

The empirical reflections facilitated by this work underscore the ongoing challenge of establishing measurable criteria for analysing journalistic quality. Similarly, media organisations have yet to find a way to rebuild audience trust and improve interaction with the public. The theoretical significance of journalistic quality for maintaining democratic stability during a crisis has been corroborated in practice during the coronavirus pandemic, underscoring the need for leading newspapers to strike a balance between economic sustainability and their social responsibility to foster critical thinking among citizens.

Newspapers have played a crucial role in informing the population about fake news, thereby helping to mitigate the effects of rumours on the public. However, content displaying ideological biases runs counter to one of the principles advocated by The Trust Project, which emphasises impartiality as essential for journalism to contribute to civic education effectively. In this sense, coverage of significant topics such as a health emergency could benefit from dissociation from political affiliations expressed in editorials, fostering greater diversity and plurality of viewpoints.

Indeed, incorporating methodologies that assess quality through journalistic added value, emphasising journalism significance and contribution to analyse the reliability of sources and the hierarchy and relevance of the facts reported, could offer a more comprehensive assessment of the coverage during the specified period in terms of journalistic quality. Additionally, it underscores the importance of promoting journalistic quality to foster critical thinking in the digital age, where audience trust in traditional newspapers wanes, and the filter bubble prompts the pursuit of ideologically-driven content.

Referências

Alberola, M. (2018, 9 de abril). La corrupción erosiona la confianza de los ciudadanos en las instituciones. El País. https://elpais.com/politica/2018/04/09/actualidad/1523275253_036368.html [ Links ]

Amoedo, A., Moreno, E., Negredo, S., Kaufmann-Argueta, J., & Vara-Miguel, A. (2023). Digital News report España 2023. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra. https://doi.org/10.15581/019.2023 [ Links ]

Arellano, E. O. (2013). Epistemología de la investigación cuantitativa y cualitativa: Paradigmas y objetivos. Revista de Claseshistoria, (12), 1-20. [ Links ]

Arendt, H. (1989). As origens do totalitarismo (R. Raposo, Trad.). Companhia das Letras. (Trabalho original publicado em 1951) [ Links ]

Arendt, H. (1967, 25 de fevereiro). Truth and politics. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1967/02/25/truth-and-politics [ Links ]

Arendt, H. (2003). Responsabilidade e julgamento - Escritos morais e éticos (R. Eichenberg, Trad.). Caminho das Letras. [ Links ]

Arendt, H. (2008). Compreender - Formação, exílio e totalitarismo (D. Bottmann, Trad.). Companhia das Letras. (Trabalho original publicado em 2005) [ Links ]

Ballestrin, L. M. (2017, 23-27 de outubro). Rumo à teoria pós-democrática [Apresentação de comunicação]. 41º Encontro Anual da ANPOCS, Minas Gerais, Brasil. [ Links ]

Barroso Fernández, Ó. (2020, 6 de julho). El totalitarismo como amenaza de la democracia. Público. https://blogs.publico.es/otrasmiradas/34079/el-totalitarismo-como-amenaza-de-la-democracia/ [ Links ]

Bartlett, J. (2018). The people Vs tech: How the internet is killing democracy (and how we save it). Ebury Press. [ Links ]

Bengoa, B. Z., Urrutia, S., Camacho-Markina, I., & González, J. M. (2020). Clics y comentarios como expresiones del dilema de intereses de los usuarios ante las noticias: El caso del agregador de noticias de lengua hispana Menéame. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (75), 327-339. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1429 [ Links ]

Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122-139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317 [ Links ]

Blanco, P. R. (2020, 22 de março). ¿A quién beneficia la avalancha de bulos sobre el coronavirus? El País. https://elpais.com/elpais/2020/03/21/hechos/1584803141_948265.html [ Links ]

Carlson, M. (2017). Journalistic authority: Legitimating news in the digital era. Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on the media system. Communicative and democratic consequences of news consumption during the outbreak. El Profesional de la Información, 29(2), e290223. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.mar.23 [ Links ]

Costa-Sánchez, C., & López-García, X. (2020). Comunicación y crisis del coronavirus en España. Primeras lecciones. El Profesional de la Información, 29(3), e290304. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.04 [ Links ]

Dahl, R. (2006). On political equality. Yale University Press. [ Links ]

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2019). Democracy index 2019 - A year of democratic setbacks and popular protest. The Economist. https://www.in.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Democracy-Index-2019.pdf [ Links ]

Feenstra, R. A., Tormey, S., & Keane, A. C.-R. (2016). La reconfiguración de la democracia: El laboratorio político español. Comares. [ Links ]

Fontecoba, N., Fernández-Souto, A. B., & Puentes-Rivera, I. (2020). Los programas de infoentretenimiento como sustituto de los debates electorales: El caso de Miguel Ángel Revilla. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (76), 59-80. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1437 [ Links ]

García, V. (2020, 20 de março). Facebook pasa a la acción: Enviará alertas de bulos “dañinos” sobre el Covid-19. El Confidencial. https://www.elconfidencial.com/tecnologia/2020-04-16/facebook-alertas-bulos-salud-coronavirus-covid-19_2551984/ [ Links ]

González-Fernández-Villavicencio, N. (2014). Métricas de la web social para bibliotecas. El Profesional de la Información. [ Links ]

Habermas, J. (2006). Political communication in media society: Does democracy still enjoy an epistemic dimension? The impact of normative theory on empirical research. Communication Theory, 16(4), 411-426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00280.x [ Links ]

Kleis-Nielsen, R., Fletcher, R., Newman, N., & Howard, P. N. (2020). Navigating the ‘infodemic’: How people in six countries access and rate news and information about coronavirus. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://doi.org/10.60625/risj-b838-pw85 [ Links ]

Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2007). The elements of journalism: What newspeople should know and the public should expect. Three Rivers Press. [ Links ]

Lacy, S., & Rosenstiel, T. (2015). Defining and measuring quality journalism. Rutgers. [ Links ]

Lapuente, V., Fernández-Albertos, J., Ahumada, M., Alonso, A. G., Llobet, G., Parrado, S., Villoria, M., & Gortázar, L. (2018). La calidad de las instituciones en España. Círculo de Empresarios. [ Links ]

Lázaro-Rodríguez, P., & Herrera-Viedma, E. (2020). Noticias sobre Covid-19 y 2019-nCoV en medios de comunicación de España: el papel de los medios digitales en tiempos de confinamiento. El Profesional de la Información, 29(3), e290302. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.02 [ Links ]

Loader, B., & Mercea, D. (2012). Social media and democracy: Innovations in participatory politics. Routledge. [ Links ]

McQuail, D. (2012). Atuação da mídia: Comunicação de massa e interesse público (K. Reis, Trad.). Penso. (Trabalho original publicado em 2011) [ Links ]

McQuail, D. (2013). Journalism and society. SAGE. [ Links ]

Negredo, S. (2020). Los españoles conectados se informaron por igual en medios y redes sociales sobre coronavirus y Covid-19. In S. Negredo-Bruna, A. Amoedo-Casais, A. Vara-Miguel, E. Moreno-Moreno, & J. Kaufmann-Argueta (Eds.), Digital News report España 2020 (pp. 42-59). Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra. [ Links ]

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2019). Reuters Institute digital news report 2019. Reuters Institute; University of Oxford. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-06/DNR_2019_FINAL_0.pdf [ Links ]

Palomo, M. B., & Sedano, J. A. (2018). WhatsApp como herramienta de verificación de fake news. El caso de B de Bulo. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (73), 1384-1397. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2018-1312 [ Links ]

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Pérez-Dasilva, J.-Á., Meso-Ayerdi, K., & Mendiguren-Galdospín, T. (2020). Fake news y coronavirus: Detección de los principales actores y tendencias a través del análisis de las conversaciones en Twitter. El Profesional de la Información, 29(3), e290308. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.08 [ Links ]

Picard, R. G. (2004). Commercialism and newspaper quality. Newspaper Research Journal, 25(1), 54-65. https://doi.org/10.1177/073953290402500105 [ Links ]

Przeworski, A. (2019). Crises of democracy. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Romero-Rodríguez, L. M., de-Casas-Moreno, P., & Torres-Toukoumidis, Á. (2016). Dimensiones e indicadores de la calidad informativa en los medios digitales. Comunicar, XXIV(49), 91-100. https://doi.org/10.3916/C49-2016-09 [ Links ]

Santos, É., & Guazina, L. (2019). Problemas de qualidade na cobertura jornalística do impeachment de Dilma Rousseff: Uma análise de seis jornais brasileiros. Brazilian Journalism Research, 16(2), 342-367. https://doi.org/10.25200/BJR.v16n2.2020.1265 [ Links ]

Schulz, W. (2000). Preconditions of journalistic quality in an open society. Hungarian Europe Society. https://europatarsasag.hu/en/blog/preconditions-journalistic-quality-open-society [ Links ]

Shapiro, I., Albanese, P., & Doyle, L. (2006). What makes journalism “excellent”? Criteria identified by judges in two leading awards programs. Canadian Journal of Communication, 31, 425-445. https://doi.org/10.22230/CJC.2006V31N2A1743 [ Links ]

Van Aelst, P., Strömbäck, J., Aalberg, T., Esser, F., Vreese, C. d., Matthes, J., Hopmann, D., Salgado, S., Hubé, N., Stępińska, A., Papathanassopoulos, S., Berganza, S., Legnante, G., Reinemann, C., Sheafer, T., & Stanyer, J. (2017). Political communication in a high-choice media environment: A challenge for democracy? Annals of the International Communication Association, 41, 3-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2017.1288551 [ Links ]

Vehkoo, J. (2010). What is quality journalism and how it can be saved. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [ Links ]

Waisbord, S. (2018). Truth is what happens to news: On journalism, fake news, and post-truth. Journalism Studies, 19(13), 1866-1878. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1492881 [ Links ]

Wood, M. J. (2018). Propagating and debunking conspiracy theories on Twitter during the 2015-2016 zika virus outbreak. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21(8), 485-490. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0669 [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2022). Novel coronavirus(2019-nCoV): Situation report - 13. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/330778/nCoVsitrep02Feb2020-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

Zúñiga, H. G., Weeks, B., & Ardèvol-Abreu, A. (2017). Effects of the news-finds-me perception in communication: Social media use implications for news seeking and learning about politics. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 22(3), 105-123. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12185 [ Links ]

Received: April 15, 2023; Accepted: February 13, 2024

texto em

texto em