1. Introduction

Contemporary society has been conceptualized, for the past three decades, as intertwined with the evolution and widespread adoption of digital media. These are always “at hand” (Levinson, 2004), and individuals are permanently connected (Katz & Aakhus, 2002), living phygital lives (Tolstikova et al., 2021). This permanent state of connectedness enables people to socialize, work, learn, and have fun anytime-anywhere, but it can also lead to anxiety, tiredness, and even addiction. As most individuals become users of digital media, a few are deliberately and consciously seeking non-use, undergoing “active, meaningful, motivated, considered, structured, specific, nuanced, directed, and productive” (Satchell & Dourish, 2009, p. 15) processes of disconnection, which may include media refusal (Portwood-Stacer, 2013), non-usage (Neves et al., 2015) and digital detox (Syvertsen & Enli, 2020). Wyatt (2003) argued that understanding non-users of digital media is as relevant and necessary to grasp the whole phenomenon as understanding users is.

The COVID-19 pandemic enhanced the use of digital media and changed users’ perspectives on their benefits and drawbacks. Screen fatigue was experienced more intensely, and more users became aware of the warning signs of addiction (Bao et al., 2020). These experiences, combined with a renewed urge to “live life” after facing many restrictions during lockdown periods, enhanced the digital disconnection trend (Nguyen et al., 2021).

As more users weigh their options concerning their digital diet and struggle to find balance in their relationship with digital media, our study sets out to understand the experiences of Portuguese teenagers who have voluntarily chosen to disconnect.

2. Motivations to Disconnect

There is considerable research about the motivations that lead to digital disconnection. Early on, Wyatt et al. (2002) suggested that a sense of delusion, disappointment, or deception when comparing expectations about the internet with actual experiences and acknowledging online risks may lead to voluntary disconnection. Later, Eynon and Geniets (2012) organized the motivations for disconnecting uncovered by different studies into five categories: psychological (e.g., attitudes), cognitive (e.g., skills, literacy), physical (e.g., access), sociocultural (e.g., family context, cultural context) and material (e.g., socioeconomic status). In their study about Facebook abandonment, Baumer et al. (2013) identified reasons such as privacy protection, the possibility of data misuse by the platform, banality and time waste, negative impact on productivity, addiction, and external pressures. A broader study about disconnection from social networking sites (SNS) by Neves et al. (2015) identified three main reasons for disconnecting: low perceived usefulness of SNS, low willingness to participate in social practices perceived as negative (e.g., gossiping, social voyeurism, self-promotion), and self-perception as diverse from “mainstream” represented on SNS.

More recently, Syvertsen and Enli (2020) argued that a general sense of overload leads individuals to personal introspection, resulting in processes of digital disconnection. The authors suggest the concepts of “temporal overload” - when digital media users lose track of time and engage in excessive use; and “space overload” - when digital media users struggle to separate physical experiences from online experiences. These states lead to physical consequences, such as weight gain, sedentarism, depression, anxiety, and stress, which, when acknowledged, may trigger the will to change. Nguyen et al. (2021) found that adult users feel overwhelmed with information, stimuli, and tasks and question the impact of digital media on their efficiency and productivity. Aharoni et al. (2021), studying news avoidance, also concluded that overconsumption of digital media leads to fear of addiction, translating into media use reduction. Thus, processes of introspection lead to negative perceptions or evaluations about the impact of digital media in daily life, which motivate decisions to cut back on digital media use or disconnect entirely, temporarily or permanently (Magee et al., 2017).

3. Strategies of Digital Disconnection

Depending on the motivations to disconnect and on specific individual features and social circumstances, digital disconnection experiences can differ significantly. In 1995, Bauer observed that not using digital technologies may be an unintentional choice (e.g., lack of access, lack of digital skills) or an intentional choice, which the author labeled “active resistance”.

Wyatt et al. (2002) suggested four profiles of non-users of digital media: resisters, “rejecters”, excluded, and expelled. These profiles result from a matrix in which the crossing axes are voluntary versus involuntary actions and never having used versus quitting. Thus, both the excluded (involuntary non-users, socially or technically excluded) and the expelled (involuntary former users, due to cost, lack of access, lack of skills) are what the authors labeled “have nots”, as their behavior is determined by external conditioning instead of deliberate choice. On the contrary, the other two profiles are the “want nots”, as resisters (voluntary non-users) deliberately decided never to use digital media (in general, but usually partially, specific devices or platforms), and rejecters (former users) have been users in the past but willingly decided to quit or reduce.

Another proposal to characterize “non-users” is presented by Satchell and Dourish (2009), who draws on Rogers’s (1983) work on technology adoption. Within this theory, laggards are those who have not yet adopted a certain technology. However, the authors argue that lagging behind in adoption differs greatly from deliberate and purposeful action. Seeking how such actions take form, Satchell and Dourish (2009) found five forms of non-adoption: disenchantment (evoking nostalgia to avoid change), displacement (users have substitute practices), disenfranchisement (lack of availability and accessibility of technologies), disinterest (users do now recognize worth in adopting a certain technology), and active resistance (users consider a certain technology negative or risky and fight its adoption).

Later, Neves et al. (2015) applied Wyatt et al.’s (2002) taxonomy to SNS and focused on resisters and rejecters. Their research led to suggesting two new categories: surrogate users (who do not have their own SNS accounts or profiles but occasionally use other people’s access for specific actions); and potential converts (non-users who are considering starting to use SNS or reactivating their SNS accounts).

Although these studies shed light on disconnection experiences, the definition of non-user profiles relies more on the motivations leading to such decisions than on the actual strategies that non-users apply to avoid, reject, quit, or reduce digital media. Aranda and Baig (2018) offer insight into such strategies by suggesting that they are shaped by two main factors: the level of control (which varies from forced to voluntary disconnection) and the duration (from short to long term). The crossing of these axes results in a new matrix whose quadrants are four different digital disconnection strategies. In the forced quadrants, the “unplanned outage” includes users who are forced to stop using digital media for a short period (e.g., no Wi-Fi available, no battery on devices), while the “infrastructure constraints” includes people who experience disconnection during extended periods without their deliberate consent or desire (e.g., being at a place without digital infrastructures, accessibility restrictions). These users are permanently seeking to reconnect since it was not their voluntary decision to be disconnected. In the voluntary quadrants, “a short break” includes users who deliberately plan to disconnect for a short period, to rest or to focus on a specific task or situation (e.g., vacation with family, not being interrupted while working on something important or to meet a deadline), and “lifestyle choice” corresponds to a more consistent change of digital usage habits, which can be a radical disconnect or simply a limitation of screen time. In these cases, nonusers are usually satisfied with their deliberate decisions and their impact on their lives. Self-regulation and self-management of digital activities are described in previous studies that do not focus specifically on digital disconnection. For example, Light and Cassidy (2014) found that Facebook users suspend and/or prevent connections to manage social relations and status, time spent online, and stress and anxiety.

Our research focuses precisely on deliberate non-usage and attempts to detail how this process occurs.

4. Digital Disconnection and Outcomes for Well-Being

Research about digital media’s impact on users’ lives is proliferous but inconclusive, as each study tends to focus more on the positive or the negative aspects of digital practices. These contradictory findings have made it challenging to determine the impact of digital media on the daily lives of their users, and a more holistic approach is needed to clarify this issue (Sewall et al., 2020). Another approach considers the impact of digital disconnection on the lives of voluntary non-users. Our research takes such an approach and focuses on well-being.

Seeking and achieving well-being is intrinsic to human life (Huta & Ryan, 2010). In general terms, two different approaches to well-being can be found since the Ancient Greek philosophy: to hedonism, well-being corresponds to brief moments when one experiences pleasure and/or happiness, whereas, in a eudaimonic perspective, well-being corresponds to the pursuit of fulfilling one’s true potential throughout life (Henderson & Knight, 2012). In hedonism, measuring well-being is subjective, as it depends on individual perceptions of positive affect, life satisfaction and happiness (McCullough et al., 2000). On the contrary, in the eudaimonic view, well-being corresponds to reaching personal goals and achievements, culminating in being a fully functioning person. Within this perspective, Ryff (1989) suggests six criteria to measure psychological well-being: self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. Keyes (1998) later argued that these dimensions concern solely the individual, but it is necessary to consider that individuals live integrated into social institutions and communities. Thus, the author adds five social dimensions of well-being: social integration (individuals feel that they are part of society), social acceptance (individuals feel accepted by other people), social contribution (individuals feel that they have value and are therefore able to contribute positively to society), social actualization (individuals believe that society has the potential to evolve and reach better states of well-being) and social coherence (individuals understand how society works).

More recent views on this issue have sustained that the hedonic and the eudaimonic views are not contradictory but complementary (Henderson & Knight, 2012; Huta & Ryan, 2010), a view we will adopt in our research.

There is emergent research on how digital disconnection experiences reflect on (physical and psychological) well-being. Vanden Abeele (2021) observes that digital connectivity is usually associated with the promise of improving daily life - more productivity, speed, efficiency, and personal time - while, in fact, many users struggle to balance the overwhelming feeling and pressure resulting from a permanent connection. The author refers to this ambivalence as “the mobile connectivity paradox” (Vanden Abeele, 2021, p. 934) and argues that acknowledging this paradox has led many users to change their digital practices, seeking a healthier and more balanced relationship with digital media. These changed behaviors take many forms, from total abstinence to reduction and self-regulation (Nguyen et al., 2021).

Baym et al. (2021) have found that short periods of digital abstinence, voluntary or not, raise awareness about the pros and cons of digital practices, which is beneficial to one’s well-being. Nguyen et al. (2021) showed that disconnecting from SNS eases the burden of constantly being confronted with new information and the pressure to be permanently connected and respond. When digitally disconnected, the participants in their study experienced feelings of relief, peace, and quietness. These findings are consistent with a previous study by Brown and Kuss (2020) about a seven-day digital detox experience, which resulted in withdrawing from social comparison on social media, thus increasing psychological well-being. Anrijs et al. (2018) found that stress levels decrease during periods of digital detox from smartphones, thus finding evidence of a positive impact of digital disconnection on physical well-being as well. Turel et al. (2018) reached similar results regarding short periods of abstinence from SNS, thus revealing that this positive effect can be reached by good management of social media time and not only through radical disconnection. In fact, Hinsch and Sheldon (2013) had already found that taking short breaks from digital media decreased procrastination, which, in turn, increased life satisfaction - and, thus, well-being. Monge Roffarello and De Russis (2019) later reached similar conclusions, arguing that a good digital media management has better outcomes than radical disconnection. In their study, limiting the time spent online and taking short breaks increased attention span and the ability to focus. The authors stress that digital well-being apps can play an important role in self-regulating digital media use, helping users monitor their digital behavior and affording some self-regulatory tools such as blocking notifications. However, their research showed that these apps are efficient in reducing distractions for short periods, thus having a positive impact on study or work, but they fail to support the development of healthier digital practices in the long run. Nguyen et al. (2021) stress another positive outcome of digital disconnection: it frees time for exploring new interests and for self-care, thus leading to increased quality of life. In addition, the authors also found evidence of a positive impact on physical well-being, namely on sleep quality.

As there is evidence that excessive use of digital media can lead to addiction, Eide et al. (2018) explored the effects of abstinence and withdrawal from digital media, finding that in digital detox situations, withdrawal symptoms were stronger for individuals that used digital media more. Stieger and Lewetz (2018) also found that social media abstinence causes withdrawal symptoms, mainly craving and boredom. Wilcockson et al. (2019) showed that smartphone abstinence causes craving but stressed that other typical withdrawal symptoms, such as mood modification and increased anxiety, were not experienced, thus considering that digital detox experiences only cause slight withdrawal. Stieger and Lewetz (2018) claim that it is relevant to consider the effect of digital disconnection on the social dimension of well-being. Previous research has established that SNS have not significantly increased the size of social circles but have changed their landscape by facilitating the maintenance of weaker social ties (Dunbar, 2016). Despite social connections being generally weaker ties, they are important as they may be a source of social comparisons, a sense of belonging, and social recognition (Dunbar et al., 2015). Thus, being absent from the digital world or unavailable for a while may lead to strong social pressure to return, particularly to social media. Participants in Stieger and Lewetz’s (2018) study reveal a sense of restlessness due to being left wondering about what is happening in the online world while they are offline, a sense of worry about other people possibly trying to reach them and being left without an answer, which fuels anxiety and leads to a reduction in psychological well-being. An increase in anxiety as a result of fear of missing out is also reported by Eide et al. (2018) and Vally and D’Souza (2019).

In general, research on the impact of digital disconnection on well-being shows how paradoxical it is, revealing evidence of being both detrimental and beneficial to wellbeing. Detrimental effects seem, however, to be mainly connected to the social dimension of well-being. Further research is needed to clarify this issue, and our research sets out to contribute to its understanding.

5. Methodology

5.1. Research questions

Our project aims to answer the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: what motivates Portuguese teenagers to disconnect from digital media?

RQ2: how does this process of digital disconnection occur?

RQ3: how does digital disconnection impact their well-being?

5.2. Research Design

Our study is exploratory, using a qualitative method, with in-depth interviews as a data collection technique and thematic analysis as a data analysis technique. Regarding ethics, our study was approved by the University of Oslo’s Ethics Committee, which developed the original study to which ours compared; informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians. Each participant chose the alias with which they wanted to be identified.

5.3. Sample

We intended to study digital disconnection among individuals between 15 and 18 years old who had already engaged in some sort of digital disconnection experience. Our sampling method consisted of announcing, through digital media channels of the main author’s university (website and Instagram), that we were looking for volunteers of this age range who could describe their digital disconnection experiences. In addition, we contacted relevant partners such as youth associations, youth sports clubs, youth activities, and study centers by email and telephone, asking them to disseminate our request on their website and/or social media. Volunteers contacted us by email, and after ensuring they corresponded to our eliminatory criteria, we selected three initial participants. Then, we used the snowballing technique to find more young people who fit into the profiles we were seeking. We wanted to have some diversity, so we selected participants that would afford gender balance and participants of all ages within the considered age range. As we got more responses from boys and 17-18 year-olds, we specifically looked online for female participants between 15 and 16, offering a € 20 Amazon voucher as compensation. Informed consent was obtained from the participants, as they were considered autonomous to decide above 15. Our sample includes 20 participants, and this sample size was determined by the fact that digital disconnection experiences are not that common among youth, by the saturation found in our data at this point (Guest et al., 2006; Morse, 2015), and to abide by the same protocol used by other partners of this comparative project.

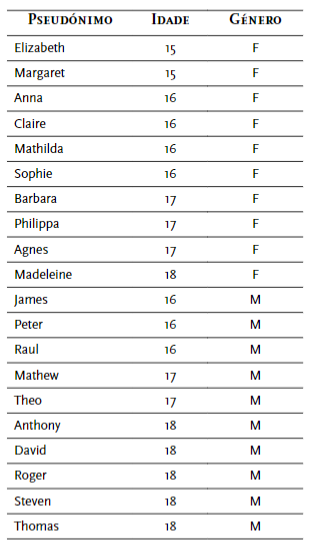

Table 1 gives us a few details about our sample of 20 participants, identified by alias chosen by themselves, here translated into English.

5.4. Data Collection Protocol

Our data collection technique was in-depth interviews, following a semi-structured script which addressed the following main topics: (a) background and socioeconomic status; (b) digital media use in everyday life; (c) perceptions and opinions on specific digital activities (e.g., social media, online gaming); and (d) digital disconnection experiences. The basis for this script was a translation of the data collection instrument used in a study conducted in the Digitox project, in Norway, with a few adaptations to the Portuguese context and additional questions. The interviews were conducted in the Spring and Summer of 2021. Because of the COVID-19 restrictions, interviews were conducted over video calls (Zoom). These conversations lasted, on average, one hour.

5.5. Data Analysis

All interviews were transcribed, and a summary of each interview was produced. We used thematic analysis (Boyatzis, 1998) as a data analysis technique, starting with a preliminary reading of the summaries. Next, a codebook was built, considering the literature review and the research questions - thus focusing on three main topics: motivations to disconnect, disconnection process, and disconnection outcomes. Table 2 displays the thematic categories and subcategories used in our coding. Then, coding was performed using MaxQDA software by one of the researchers. After the first round of coding, which was circulated and discussed among researchers, a second reading was performed to spot emerging relevant topics that were not included in the initial codebook. New themes were added, and the corresponding coding was conducted in a second round. This data analysis protocol enabled us to focus on our research questions while, at the same time, not missing relevant new topics.

6. Findings

6.1. Motivations to Disconnect

In our sample, five participants had experienced digital disconnection only because it was mandatory in and inherent to specific situations, such as sports competitions, scouts’ camping, and summer camps. The other 15 had decided, consciously and voluntarily, to disconnect from digital media and were able to shed light on the motivations that led to this decision.

The main motivation was the realization that they could do something more useful or productive with their time instead of scrolling down social media or engaging in multiplayer games online. In the words of Madeleine (18 years old), “I was feeling really bad. Instagram was controlling my life. My time was not being well used”; and in the words of Anthony (18 years old), “I realized I was wasting my time”. This realization was usually associated with something lost, such as a decline in academic performance, relationships that drifted apart, abandoning extra-curricular activities, or spending lesser time with their family.

In some cases, the perception of excessive use of digital media and its negative impact on their lives is so strong that they perceive and describe themselves as addicts. For example, Sophie (16 years old) says: “Instagram’s algorithm is so well designed that it showed me exactly what I like to see, so I stayed online for very long periods without even realizing time was going by”.

For most participants, this was a progressive and cumulative process, but many describe defining moments in which they realized they needed to change. For Anthony, it was a day he missed school because he was feeling sick and spent the whole day in bed using his smartphone without even eating. That was the first time he saw himself as an addict. For Margaret (15 years old), it was when her mother sent her a message through WhatsApp asking her to come and have dinner with her family because that was the best way to get her attention.

Another important motivation is identifying social media as the cause of anxiety. If they are not connected, many participants describe feeling fear of missing out, as they cannot follow what is happening in their circle of friends, with the influencers and brands they like, and the world in general. Theo (17 years old) gives us an example:

sometimes I’m home, and my friends post an Instastory of someone falling off their bike or fighting at a club, and they are laughing; they seem to be having so much fun. I feel bad for missing it. And they message me inviting me to meet them because they are having so much fun, so I feel social pressure.

However, being constantly connected also generates anxiety stemming from social comparison. They feel excluded if others are engaging in some activity they were not invited to, feel depressed if they cannot uphold the lifestyle of friends and influencers, and feel ashamed about their body and image if it doesn’t meet the standards of Instagram or TikTok. Mathilda (16 years old) gives us her testimony:

mentally, being on Instagram was torture because I was always comparing myself to others. If some of my friends went out and seemed to be having fun, I would feel bad because I was not having fun, or I would feel sad because I was not invited. I compared myself to others, and I always felt worse. I would see influencers leading dream lives, and I was just at school. And then I felt miserable all day.

Creating content is another source of anxiety as, if you don’t post, you become irrelevant, and if you post, waiting for others’ reactions and validation can be very stressful, as well as dealing with indifference or negative comments. Agnes (17 years old) says: “before, I was always seeking the attention and approval of others on Instagram. And I felt really bad when I didn’t get it”. While falling into the traps of social comparison on social media, they also develop a critical view of it. They are aware of the lack of authenticity and the superficiality of the carefully curated and constructed content that is particularly characteristic of Instagram. For example, Theo states:

Instagram is an illusion. People only post their best photos; they build a perfect image of themselves, so different from what is beneath them. Most people don’t realize this. Girls feel so bad about their bodies, and boys do as well. It’s awful. Friends have asked me for help because they were afraid they would become anorectic or bulimic trying to be like other girls on Instagram.

They struggle to acknowledge many of the downsides of the digital world and the social pressure - particularly peer pressure - to continue to be a part of it. Anthony shares how he coped with this:

There was a stage in which I uninstalled Instagram and was completely cut out of my circle of friends. They met, and I was left out. I also uninstalled WhatsApp, and I was totally isolated. As I cared about my friends, I decided to use a condensed version of Instagram, Threads. And I turned off WhatsApp notifications and only check it in the morning, at lunch, and night, for five minutes each time.

For some participants, experiencing mandatory digital disconnection experiences such as the cases we described above, or vacations at places without internet connection, was so positive that they decided to make some changes in their digital practices. In these cases, the main motivation for disconnecting was not the realization that excessive use of digital media was negative for them but, instead, the realization that digital disconnection periods were positive for them.

6.2. The Process of Digital Disconnection

From our participants’ experiences, we were able to identify two main trends: disconnecting radically or self-regulating their digital practices. Those who disconnect radically abandon digital practices that they consider negative for them, while self-regulators focus more on cutting back on the time they spend online. Both groups find sticking to their decisions challenging, face setbacks, and struggle with contradictions and impulses. In our sample, there were four radical disconnectors - all boys; four progressive disconnectors - two boys and two girls; and seven self-regulators - two boys and five girls. The average age of the (radical and progressive) disconnectors tends to be slightly higher than that of self-regulators.

The radical disconnectors usually identify a specific practice as the source of their addiction and/or anxiety and decide to abandon it. The most common are social media - particularly Instagram - but also online multiplayer gaming and pornography. Some “went cold turkey” and uninstalled the social media apps on their phones; some even deleted their profiles so there was no point in installing the apps again, and others sold their consoles. Others preferred to cut down progressively, particularly on social media, and set progressive goals such as dedicating one hour a day, 45 minutes the next week, half an hour, and so on, until they feel capable of uninstalling. The progressive process is a daily battle, and more vulnerable to peer pressure, as Roger (18 years old) shares:

my friends from school would say “Hey, I DMed [sent a direct message] you on Instagram, and you didn’t answer? Why aren’t you answering?” and I tried to explain to them what I was trying to do and what I was going through. Not all of them understood.

A common challenge is replacing a digital activity with another. For example, Madeleine abandoned Instagram and started using YouTube more. Anthony was able to quit watching online pornography but now uses an app to meditate. To face this challenge, other participants, such as Barbara, James and David started engaging more in offline activities such as sports, learning how to play an instrument, or simply hanging out with friends face to face. The progressive disconnectors experience more ups and downs in their process and are more prone to relapsing into their previous habits.

The self-regulators share more positive views on the digital world than the radical disconnectors. The first acknowledge risks and opportunities, while the latter tend to focus on the “dark side” of the internet. Thus, self-regulators believe it is possible to reach a point of balance in which they can harvest the advantages of the online world - for learning, studying, and connecting -, while at the same time coping with the risks. They tend to focus more on managing their time online, while the radical disconnectors are more worried about what they do online. Self-regulators also tend to engage in progressive disconnection processes, but their goal is not to completely disconnect but rather to reach an amount of time that they find acceptable or appropriate to dedicate to online activities.

If peer pressure is the main cause of setbacks and relapses - as David (18 years old) tells us: “sometimes I am talking to someone on Instagram, and my daily 15 minutes are over, and I stay for a bit longer, and then I feel so guilty, I should have used my online time better” -, it can also be a source of motivation and help. Our participants agree that undergoing this disconnection journey had an impact on their circle of friends. Some relationships drifted apart because the easy online connection was no longer available, while others were reinforced by the commitment and effort it took to meet face to face. Our participants became closer to friends who were also struggling with excessive digital media use. They formed informal support groups that became safe spaces for discussing concerns, guilt, difficulties, and possible solutions. Anthony shared his experience:

this process became easier because I sought friends to whom I could talk about what I was going through. If we are struggling with difficulties in sticking to our goals, it’s much easier to overcome them as a group than if we are alone. Sometimes I don’t know if what I am feeling is normal or not, and it helps to discuss it with others and learn from their experiences.

In our participants’ discourse, their choice of vocabulary was very vivid. They talk about “addiction”, “triggers”, “dopamine rush”, “withdrawal”, “relapses”, “failure”, and “guilt”. Many see themselves as addicts but are trying to cope with the problem on their own and relying on the help of friends struggling with the same problem. They haven’t sought the help of parents, teachers, or professionals because they see the adults around them struggling with the same addiction, even less aware of it than they are. For example, Theo describes his household in the following way:

my parents are also addicted to digital media. They spend so much time on their smartphones! Sometimes I watch a soccer game with my dad on TV, and he is on Facebook instead of paying attention to the game. My mum texts while she is watching her favorite soap opera. And my sister is the worst! She is always on TikTok.

Regardless of being more or less successful in reaching their disconnection goals, our data revealed that young people are struggling while trying to cope with the change they want to make in their lives.

6.3. Outcomes of Digital Disconnection

In general, our participants state that their lives improved because they decided to disconnect from the digital world. However, these improvements are also felt after a while of compliance because the immediate effect is negative.

At the beginning of their disconnection journey, they feel anxious, particularly those who disconnect from group activities such as social media and online multiplayer gaming. They lose track of what is going on in their circle of friends, and some of them even feel guilty when their friends don’t understand their decision and complain because they are not available anymore. Also, they start to be excluded from invitations and arrangements made exclusively online. Mathilda describes her experience:

sometimes, I miss knowing what my friends are up to, what they do outside school. Are they interesting? What do they like? What do they do in their free time? Now I have no idea. I used social media to find common ground, to have topics to start conversations, and I had to learn how to connect with people in other ways.

However, some participants consider that, in the long run, they now have a more authentic and solidary group of friends. They believe that the connections they lost were superficial, and those who made an effort to stay in touch and hang out offline are their true friends. Anthony gives us his perspective:

I have lost touch with a lot of people, but I realized that only happened with people that were not important in my life. I occasionally liked their stories. Does that matter? If someone is important to me, I will call that person. And if I am important to someone, that person will call me. And when we meet, we have deeper conversations; it’s almost magical. I have realized who my true friends are, and that has made an incredible difference in my life.

Boredom was another problem they reported dealing with at the beginning of their disconnection journey. They were so accustomed to dedicating their free time - and even beyond that - to online activities - particularly social media, that they didn’t know what to do with the free time they gained or how to entertain themselves. Roger told us about this:

Before, whenever I was bored, I would turn immediately to my smartphone and scroll down social media. In response to boredom, my brain immediately sought a dopamine rush; I clicked and got it automatically. I had to learn how to deal with boredom.

This challenge was overcome by dedicating the newly released time to activities they had neglected, such as studying, romantic relationships, and even family. In other cases, they finally ran out of the “I don’t have time” excuse and gained motivation to pursue forsaken projects and goals, such as starting a new sport, learning to play an instrument, and reading.

Once the time previously dedicated to online activities was replaced with others, and their circle of friends stabilized, the positive outcomes became more evident. David improved his grades and is now on the right track to fulfilling his dream of becoming a doctor, and considers that “before, I had ‘brain fog’, I couldn’t concentrate on anything. I was just there, and my thoughts controlled me. Now I can focus on classes, without any problems”. He also emphasizes a sense of accomplishment: “now I use my time much better. I don’t procrastinate doing nothing on my smartphone anymore”. Barbara (17 years old) learned how to play the guitar. Anthony improved his relationship with his girlfriend and motivated her to start her own digital disconnection journey. Agnes now values spending some evenings watching television with her family instead of alone in her room.

Particularly the girls experienced improvements in their self-esteem and self-image acceptance. Philippa (17 years old) gives us her testimony:

I saw other girls on Instagram, and I thought, “I wish I were as pretty as her”, and I felt unhappy about my physical appearance. Now I realized I was focusing just on the positive aspects of others and on the negative aspects of myself. Now I try to enjoy my life offline and feel happier.

By distancing themselves from the constant social comparison that social media triggers and questioning the beauty standards that emerge in those platforms, they now feel better about themselves, their bodies, and their lifestyles.

Our participants emphasize that their digital disconnection processes were important self-knowledge and self-improvement journeys. Being successful in reaching the goals they have set for themselves also affords a sense of accomplishment and self-fulfillment, as David describes:

I feel proud; I feel that I am holding my commitment if I use digital media less. That’s how I feel when I don’t use the smartphone. And if I use it for too long, I feel guilty because I wasted time that I could have used better, and I didn’t study as much as I should have. Not using the smartphone helps me make the best of my time and feel good about myself.

Philippa believes she is now more authentic and lives a more real life. Madeleine finds fulfillment in her disconnection progressive achievements and believes she is now more autonomous, critical, and prepared to become an adult. Margaret is very committed to setting a good example for her younger siblings. Anthony is thinking about how so many young people could benefit from digital disconnection and is trying to find a way of sharing his experience and positively impacting the world without resorting to digital media.

7. Discussion

Among the various motivations to disconnect from social media discussed in the literature, our study highlights, on the one hand, the importance of the usefulness of time and productivity for teenagers. This issue has already been identified by Nguyen et al. (2021) in adults and framed within the contemporary neoliberal and capitalist ideology associated with labor, user-generated content, and the use of social media (Fuchs, 2018). On the other hand, issues such as privacy protection and the possibility of data misuse by digital platforms, as mentioned by Baumer et al. (2013), are absent from our data, indicative of teenagers’ lack of media literacy (Pereira & Brites, 2019).

Our research further reveals that negative perceptions about one’s use of social media are not only a common root to diverse motivations for digital disconnection (Magee et al., 2017) but also, for our sample of teenagers, associated with a sense of lack of self-control, as Aranda and Baig (2018) had already pointed out, as all of them describe themselves as social addicts, at some point of their lives.

One overarching feature of the digital disconnection phenomenon is, therefore, struggle. Our sample struggles with forming a perception about their own use of social media, as they acknowledge both benefits and downsides to their social media practices. For example, considering social media scrolling a waste of time contradicts fear of missing out. The motivation to disconnect emerges from a tipping of this scale that balances contradictory perceptions about the impact of digital media on one’s life to the negative side.

Our sample of “rejecters” (Wyatt et al., 2002) struggles with finding a digital disconnection strategy that works, ranging from radical disconnection to self-regulation, with digital breaks. Self-regulation is the predominant strategy, aligned with Monge Roffarello and De Russis’ (2019) argument that self-regulation and management have better outcomes than radical disconnection. Regardless of each option, they take steps forward and backward, noticing achievements and relapses, habits and changes. These teenagers feel that asking adults - parents or teachers - for help is useless, as adults are also perceived as digital addicts. Instead, they rely on peers with whom they share a digital disconnection journey for support.

Finally, they struggle with evaluating the impact of their decisions on their lives. Most of our participants report improvements in their lives as a result of their digital disconnection - focus and learning (Vanden Abeele, 2021), health and well-being (Baym et al., 2021), self-image and self-esteem (Brown & Kuss, 2020), genuine and meaningful friendships with peers. However, they also report problems - anxiety and social exclusion (Nguyen et al., 2021) and boredom (Stieger & Lewetz, 2018). Overall, our in-depth interviews revealed that digital disconnection is a process that negatively impacts the well-being of those who choose to undergo it during an initial adaptation period but has a significant positive impact on those who are able to overcome the hardest earliest times. However, some participants also stress that it is an ongoing process with successive challenges.

We acknowledge the limited size of our sample and the fact that our method was based on self-reported data and thus vulnerable, on the side of researchers, to interviewer bias (the influence that the interviewer’s personal characteristics and way of interacting, including words used and information disclosed about the study, can have on the interviewees) and confirmation bias (tendency, in data analysis, to interpret data in a way that confirms preexisting beliefs or hypotheses); and to social desirability bias (participants’ tendency to answer in a way they believe is socially accepted and/or valued, or that they believe will please the researcher), on the side of participants (Morse, 2015). Nevertheless, our study was the first approach to a topic that had not been studied in the Portuguese context yet and was able to point out directions for further research, as is the purpose of exploratory research (Creswell, 2009).

8. Conclusion

Our study with 20 young people between 15 and 18 years old who had already engaged in digital disconnection experiences revealed a variety of motivations, strategies, and well-being outcomes. Among those who consciously chose to disconnect from digital media, motivations arose from realizing that digital media was not bringing enough benefits for the amount of time they took from users. Specific forms of digital media stood out as particularly problematic for young people, especially social media. This realization seems to be strongly influenced by media discourses on the issue and is evident in the vocabulary and associations used by our respondents related to “addiction”.

Radical disconnection is rare, especially during the pandemic, and can appear as a solution to a dramatic problem in young people’s lives, but it can also be reverted. More often, participants attempted to self-regulate their use of digital when they acknowledged the advantages of those platforms, as well as their drawbacks. This is not a linear process but rather filled with attempts and reversals as unexpected feelings such as boredom arise. When young people grow different leisure and social habits, they experience positive outcomes of disconnecting from the digital.

The study’s contribution stems from the focus on young people, particularly teenagers mastering their self-regulation mechanisms and learning how to balance their relationship with family and peers, but also social institutions like school and the media. The fact that issues concerning how algorithmic digital platforms work, datafication, and commercial exploitation were not brought about by our participants points out the need to develop the media literacy of Portuguese teenagers so that they can understand better how contemporary social media work and how they can cope with them in an informed, critical, responsible, and safe manner. Additionally, the realization that teenagers struggle in their digital disconnection journeys and not turning to adults for help is also a concern. It entices adults to reflect on their own digital media use critically and challenges the academia, policymakers, and caretakers of children and teenagers to find new ways to support them in this dimension of their development.

The social diversity of the sample was not as high as we intended it to be. This can be listed as a limitation of the study, as experiences from teenagers from lower socioeconomic status might indicate more of the struggles young people go through in using and interrupting their use of digital media. Future research can look more deeply socioeconomic differences among young people.

texto em

texto em