Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Comunicação e Sociedade

versão impressa ISSN 1645-2089versão On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.40 Braga dez. 2021 Epub 20-Dez-2021

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.40(2021).3436

Thematic Articles

Prime Time Television News and Communication Strategies in Pandemic Times

iInstituto de Comunicação da NOVA, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

iiUniversidade Lusófona, Lisbon, Portugal

iiiInstituto de História Contemporânea, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

A pandemia de covid-19, declarada pela Organização Mundial de Saúde a 11 de março de 2020, teve um impacto imediato no quotidiano das sociedades globalizadas. No ocidente, a doença desafiou a democracia e as liberdades individuais e cívicas, ao mesmo tempo que demonstrou a centralidade do Estado e dos governos na gestão da crise. Para a concretização das orientações emanadas pelos responsáveis políticos, foram centrais as estratégias e dispositivos comunicacionais de executivos governamentais e autoridades sanitárias, assim como a sua capacidade para influenciar a agenda dos media dominantes. Este artigo objetiva refletir sobre as estratégias de comunicação utilizadas pelo governo português na gestão da crise e os seus reflexos na cobertura jornalística televisiva, analisada a partir de um estudo empírico que incide sobre os 3 primeiros meses da propagação do vírus em Portugal. Utiliza-se uma metodologia de análise de conteúdo, quantitativa e qualitativa, com base em categorias unívocas pré-determinadas sistematizadas no programa Excel. Inicia-se a exposição apresentando alguns elementos de enquadramento político, social e comunicacional que envolvem o desenrolar da pandemia ao longo do ano de 2020, no mundo e em Portugal. Em seguida, sintetizam-se tendências e estratégias de comunicação de organizações internacionais e nacionais. Por fim, os resultados da análise empírica são apresentados, discutidos e interpretados da perspetiva das estratégias de comunicação das instituições de saúde pública sobre a cobertura jornalística da pandemia.

Palavras-chave: cobertura televisiva da pandemia; comunicação de saúde pública; covid-19; Portugal; jornalismo

The covid-19 pandemic, declared by the World Health Organisation on 11 March 2020, had an immediate impact on the daily life of globalised societies. In the west, the virus has defied democracy and individual freedoms while demonstrating the centrality of the State and governments in managing the crisis. Communication strategies of governments and health authorities and their ability to influence mainstream media agendas were paramount in the deployment of public health restrictions and guidelines. This paper reflects on the communication strategies used by the Portuguese government during the covid-19 crisis and on their impacts on television coverage. This study was based on an empirical analysis of the first 3 months of the pandemic in Portugal by using a quantitative and qualitative assessment of news content and pre-determined systematised univocal categories. We start by presenting the global and national political, social and communicational frameworks in 2020, followed by a summary of trends and communication strategies of national and international organisations. The results are presented, discussed and interpreted from the point of view of the media coverage and communication strategies used by political and health authorities.

Keywords: television coverage of the pandemic; public health communication; covid-19; Portugal; journalism

1. The Pandemic as the Dominant Scenario in Daily Life

The pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus changed, in 1 year, the global society. It also prompted a host of analyses and reflections on its consequences in domains such as geopolitics, democracy, governance, economy and health. The spread of the pandemic, which began, at the end of 2019, in the Chinese city of Wuhan, reshaped the spatial reach of neoliberal globalisation, highlighting its fragilities and perversions: low-wage industry and services; precarious and low-skilled work of migrants and women; high value-added financial and technological services; inequality in the access to housing, education, mobility, health and social protection. The following characteristics were identified in the transmission pattern of covid-19, referred to as “3C”: (a) crowded places; (b) close-contact settings; (c) confined and enclosed spaces (Fujita & Hamaguchi, 2020).

The disease also exposed the risks inherent to the global value chains (Nimmo, 2020), namely the dependence of hundreds of countries on a single provider of medical supplies, such as masks and ventilators (EUA São Acusados de Reter Itens Médicos Destinados a Outros Países, 2020). At the same time, it highlighted the existence of a hierarchy of access to those essential goods based on the capacity to pay, or pressure, the suppliers. Among European Union (EU) countries, these strategies also became apparent (Caetano, 2020; França Confiscou Dois Milhões de Máscaras Destinadas a Espanha e Itália, 2020), although the European Commission subsequently adopted a coordinated response to the pandemic (Comissão Europeia, n.d.-a), ordering vaccines for the 27 countries in the block (Comissão Europeia, n.d.-b).

International organisations, such as the United Nations (UN), the World Health Organisation (WHO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the World Bank, and global organisations and associations in different areas, such as Freedom House, The Economist (democracy index) or Reporters Without Borders (world press freedom index), have pointed out phenomena that were aggravated by the health crisis: (a) inequalities among and within countries; (b) sovereign debt crisis and consequent State failure; (c) fading of democracies and rise of populism and authoritarian states; (d) collapse of the health systems; (e) inequality in the access to vaccines; (f) the role of technology companies and the media (mainstream and social networks) in managing these phenomena.

Given that the virus and its propagation were unknown, the preventive measures and countermeasures adopted by the WHO (World Health Organization, n.d.-a) were inspired by the information released by China, the first country to face the pandemic. With the help of the UN, the direction of that international organisation made global coordination possible, despite the criticism and reservations of some leaders and specialists.

The lockdowns activated in a large number of countries became another contributing factor to the deepening of inequalities (Stiglitz, 2020) since most countries are unable to support, through grants, the small enterprises forced to close down and the workers. Among them, significant differences exist: some can carry out their activity through telework, and others watch their jobs, generally precarious and low-skilled, be destroyed, particularly in countries where tourism makes up a significant portion of the national income (Amaral, 2020). Therefore, countries with a greater capacity to aid enterprises and workers, such as Germany, are more protected; those without a financial buffer or more dependent on tourism, such as Portugal, are more vulnerable. In this context, and as an expression of the epidemiological characteristics and of the guidelines necessary to fight the virus, inequalities deepen among countries and workers, gender relations become more extreme (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020; Soares, 2020), and the gap between age groups widens (Georgieva et al., 2020).

From a health standpoint, as the year progressed, there was an increase in the knowledge on the transmission of the virus; the symptoms to which it is associated; the effects of the disease; the sequelae; case fatality; mutations; the variety of available tests; the adequate medication; the potential of the vaccines and immunity levels (Leiria & Albuquerque, 2020). In the health field, it became evident that there was a need to reorganise health systems, coordinate human and material resources, emphasise the specialisation and number of professionals, and strengthen preventive and public health measures. The attempts to introduce, in Western countries, virus tracing apps clashed with civil freedoms and fuelled the debate around the dilemma concerning two value systems that are difficult to harmonise: privacy and security of individuals (Figueiras, 2021). While in autocratic countries, these functionalities were immediately introduced in mobile devices, without the need for consent, in western democracies, the access to the citizens’ private data sparked discussions about surveillance and privacy. It required a more complex technology architecture and more time for these instruments to be made available (Figueiras, 2021).

The first statements issued by the Portuguese authorities on the new coronavirus date back to 15 January 2020, when the director-general of health, Graça Freitas, told journalists that “there is not a great probability of it reaching Portugal: even in China the outbreak has been contained; for the virus to reach us, someone would have had to travel from the affected city into Portugal” (Pereirinha, 2020, para. 2). A week after, due to the outbreak of cases in countries and regions outside Europe with direct flights into the country, three hospitals were placed under alert status. On 24 January, the first two cases were confirmed in France, and evidence started to appear suggesting that the virus may be circulating in many other countries. In the following weeks, there is a worsening of the global situation and the European one, namely Italy. In Portugal, the cases of infected citizens working abroad gain prominence in the media. On 27 January, the Directorate-General for Health (DGS) issued guidelines for enterprises to implement preventive and containment measures. On 2 March, the first two cases of people infected with covid-19 were confirmed in the country, with the chain of transmission being traced back to Italy. The Portuguese government sends an order to public services requiring them to draft contingency plans for the outbreak. On 11 March, the WHO declared the disease a pandemic and warned of “alarming levels of spread and severity” and “alarming levels of inaction” (World Health Organization, 2020, para. 6). In Portugal, the state of alert is decreed by the prime minister the following day, in line with the guidelines of the WHO, which identifies Europe as the new centre of the pandemic. On March 18, the president of the republic declared the first state of emergency, which would end on 2 May, despite some measures remaining in place until the end of that month and in the following months.

The DataReportal (Kemp, 2020) found that the world changed drastically in the first three months of 2020 due to the pandemic, a change that became more pronounced throughout the year, in digital behaviour and consumption, with billions of people were in lockdown at home. Anxiously following the evolution of the disease, audiences consumed more television and news while significantly increasing their use and consumption of all other devices and content.

The same trend is pointed out in the 2021 report (Kemp, 2021), with a very significant increase in the number of hours spent watching television/news and using other devices. This scenario generated by the covid-19 pandemic had consequences for mainstream media, with advertising being drastically reduced and migrating to the digital environment. In Portugal, State aids to the media (Bourbon, 2020) and the context of the pandemic led to an adjustment in audiences’ information needs and the conditions for a journalism guided by civic responsibility and responsible citizenship. Television, which many authors had deemed dead (Carlón & Fechine, 2014; Katz, 2009; Scannell, 2009), recovered much of its social and domestic centrality, opening up to the information in real-time and filling prime-time slots with the theme of the pandemic.

Against this international and national backdrop, it is important to consider the communication strategies that were institutionally adopted to deal with the pandemic. Our goal is to understand the impact and influence of these proposals and guidelines on the patterns and characteristics of the covid-19 pandemic news coverage in the generalist channels RTP1, SIC, TVI and CMTV. These channels were dominant in terms of prime time television news during the period corresponding to the first state of emergency and the subsequent lockdown easing plan of the government. We assume that this corresponds to a period of acknowledgement of the disease, not only among health professionals but also by the media. In that sense, the analysis of the television news coverage is also an indicator of the advancements and hesitations in that scientific and everyday learning process.

Through content analysis, we research the themes, protagonists and settings with greater visibility. Furthermore, we identify the signs of contamination of the news rhetoric by the discourse of the government and health authorities and review the areas of specialisation, institutional representations and independence levels of television commentators. Considering these elements as a whole, we reflect on the “seizing” of television channels by communication strategies and definition of the agenda by the executive power and health authorities, also reflecting on the “counterstrategies” with which television journalism seeks to affirm its autonomy and the singularity of its brand.

2. Communication and Media at the “Onset” of the Pandemic

Communication about the pandemic became a concern for the international and national institutions, in the sense of providing adequate information to political decision-makers with a view to the implementation of health measures of containment. The media (mainstream and social media) took on a relevant role as mediators between the various social actors. A variety of strategies involving different levels of actors and objectives can be identified: (a) collection, recording and processing of data about the pandemic; (b) communication strategies developed by health organisations (Vraga & Jacobsen, 2020); (c) government communication, to public health guidelines and information of public interest; (d) indoor and outdoor information from organisations; (e) information provided to the media and journalists; (f) information transmitted by the media; (g) interpersonal communication. In addition to these strategies, there are, across the board, campaigns to combat fake news, mainly on social media (Direcção-Geral da Saúde, 2020; Europol, n.d.).

The collection, recording and processing of data about the pandemic is a global endeavour undertaken by the WHO through a universally accessible website (World Health Organization, s.d.-a), analysing trends and elements by country. That same organisation provides information to citizens by publishing a newsletter and guidelines for journalists in the “Newsroom” section and offering specialised training to these professionals (World Health Organization, n.d.-b. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (n.d.) also created a section on its website to support the response of countries and governments to covid-19 and help control disinformation2.

The communication strategies of the WHO and Unesco around covid-19 are replicated by other institutions, such as the IMF. The IMF has been following the economic and social crisis caused by the pandemic, providing access to a newsletter and the IMFblog, where economists and specialists with different outlooks present analyses, assessments and proposals. Along the same lines, the EU has activated an online communication device to publicise completed and scheduled actions to combat the pandemic and to support the member states, such as the coordinated purchase of vaccines and the implementation of common crisis management strategies, support lines and recovery plans (Conselho Europeu, n.d.-b). It also shares with the institutions mentioned above the concern about disinformation (Conselho Europeu, n.d.-a). Therefore, the document Tackling Coronavirus Disinformation: Getting The Facts Right (European Union, 2020) sought to propose specific measures to increase the resilience of the EU, such as supporting fact-checking devices and institutions and the researchers working on this topic, intensifying the strategic communication capabilities of the EU and strengthening the cooperation with international partners, while ensuring freedom of expression and pluralism.

Corporate organisations also deployed specific communication strategies as the pandemic set in. For example, the global advisory firm FTI Consulting issued the document Covid-19: Communication Strategies For Your Organization, in which it proposes the adoption of measures to provide targeted information about security and changes to the services and operations of companies (Capodanno, 2020).

With regard to health communication strategies, guides have been published, such as those from the WHO and the centres for disease control and prevention (e.g., the ones from the United States, containing work about other epidemics, like ebola and zika). Associations such as the World Medical and Health Policy (Vraga & Jacobsen, 2020) and others in the field of medical and hospital care (Ontario Hospital Association, n.d.) consider new strategies in the field of health communication for covid-19 and draw attention to the need to distinguish information aimed at professionals and information aimed at the average citizen. For the former, a set of mechanisms for quick access to the available scientific information must be created. For the latter, communication should be reliable and credible, show empathy, call for responsibility, individual autonomy and public involvement, avoid the politicisation of the measures, and create a non-governmental control unit. The threat of disinformation, mainly on social media (Cinelli et al., 2020), is identified by all institutions and systematised into three challenges: information overload, the uncertain nature of the information and disinformation. These challenges, associated with the rapid evolution of the pandemic and the gaps in scientific knowledge on the new virus, must be countered through a precise communication of the core messages for specific audiences, as well as by monitoring the information of mainstream and social media, to combat myths and conspiracy theories.

In Portugal, the Plano Nacional de Preparação e Resposta à Doença por Novo Coronavírus (Covid-19) (National Plan for Preparedness and Response to the Diseased Caused by the New Coronavirus) was drawn up by the DGS (Correia et al., 2020), in line with the WHO and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, n.d.). The chain of command and control, which is responsible for the leadership and coordination regarding the epidemic at the national level, is composed of the Ministry of Health and the DGS. This central core is joined by other areas, such as education, internal affairs, justice, labour, social affairs and economy. The DGS collaborates with the National Institute of Health Ricardo Jorge to collect and refine data and the Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (Portugal). The communication strategies involve a website (https://covid19.min-saude.pt/), daily press conferences broadcasted live on Facebook (Ramos & Jerónimo, 2020), a daily epidemiological bulletin published on the website of the DGS, the distribution of supplies to health organisations and professionals and directives, norms and other guidance geared towards different types of public and private agents and the citizens. This directorate-general also promoted an agreement with television stations, under which these stations comply with standards of information that are compatible with the accuracy and quality of information about the pandemic (“Pivots da RTP, SIC, TVI e CMTV Juntos a uma Só Voz Contra o Covid-19”, 2020).

Though the journalistic coverage has kept abreast of pandemics, it never obtained the level of visibility reached with covid-19. The memory of the so-called Spanish influenza, pneumonia (1918/1919), still lingers in some of the survivors and is a topic covered in some newspapers at the time, including Portuguese ones (Esteves, 2020). The titles reported on the characteristics of the disease, its national and international spread, the death toll, the preventive health actions, and the guidelines to be followed. Other pandemics, such as HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, SARS (China, 2002) or ebola (Western Africa, 2014), have received media attention.

The acknowledgement of covid-19 as having news value and an object of research for media studies was almost immediate in a media system dominated by the digital environment. Recently published studies (Ogbodo et al., 2020) show that the global media conglomerates promptly made a systematic news coverage of the pandemic. However, the way it was framed might not have been sufficiently effective in communicating the main measures of containment of the disease (Yves, 2020). At the origin of this insufficiency is the lack of a concerted strategy, on the part of the health agents and the media, to favour transparency regarding the epidemic scenarios and the clarity of the prevention messages (Organização Mundial da Saúde, 2018). On the other hand, the proliferation of digital devices and the circulation of content between institutional broadcasters, such as mainstream media, and network broadcasters/users, tend to increase information chaos, misinformation and fake news. To minimise these situations, fact-checking mechanisms are being created, such as the programme Polígrafo in SIC.

In Portugal, in the assessment of Lopes et al. (2020), during the state of emergency, the news media took on a clear role of guiding citizens towards disease-preventing behaviours, “seeking to become another front on the fight against the pandemic, which could have been important in helping the country stay at home” (p. 207). In the survey to journalists carried out by those authors on the topic of the journalism conducted during this period, 92.2% assumed that editorial choice, “a choice never before seen in democratic Portugal post 25 April 1974”, and which they distinguish from the practice of directing the public towards supporting certain political choices (Lopes et al., 2020, p. 211). However, the authors also stress that official communication did not suffer changes as profound as those needed by the journalistic field; it was noted that the political entities and health authorities did not always respond to questions and information requests, nor did they provide additional explanations requested by editorial offices (Lopes et al., 2020, pp. 226-227).

From a different angle, although the social responsibility of journalism is undeniable, this activity has been subject to great constraints, not only internal ones but also those stemming from the epidemiological crisis. Beyond these circumstances, there are also pressures from authoritarian governments and democratic ones that seize this opportunity to restrict freedom of expression and pluralism. Thus, Freedom House (2020) finds that:

the COVID-19 pandemic has fueled a crisis for democracy around the world. Since the coronavirus outbreak began, the condition of democracy and human rights has grown worse in 80 countries. Governments have responded by engaging in abuses of power, silencing their critics, and weakening or shuttering important institutions, often undermining the very systems of accountability needed to protect public health. (para. 1)

In analysing the role of the internet in the pandemic, that same institution states, on the one hand, that there is a “dramatic decline in global internet freedom” (Freedom House, 2020, para. 3) and, on the other hand, that big technology companies, though generally reluctant, have implemented devices to prevent disinformation.

A similar trend is noted by the organisation Reporters Without Borders (2020), which, in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index, considered “the coming decade ( … ) decisive for the future of journalism, with the Covid-19 pandemic highlighting and amplifying the many crises that threaten the right to freely reported, independent, diverse and reliable information” (para. 1).

This statement is confirmed by the various studies that stress the media and journalism’s responsibility and show the pandemic’s impact on consumption, such as television news. In the first case, in a study developed in Australia (Thomas et al., 2020), based on an analysis of online articles from national newspapers, research was conducted to determine who was responsible for combating the pandemic. Regarding the increase in consumption of television news, an exploratory study of Casero-Ripollés (2020), based on secondary data from the American Trends Panel of the Pew Research Center in the United States, compared periods prior to and after the outbreak and concluded that the pandemic had reactivated the viewing of news, via online press but particularly on television, providing citizens with valid knowledge about the spread of the virus.

3. Empirical Study: An Approach to the “Dawn” of the Pandemic

3.1. Material and Methods

The corpora of this article comprise two data sets relating to news blocks of four generalist television channels in Portugal.

The first refers to the newscasts of RTP1, SIC and TVI, between 2 March 2020, when the first cases of infection in Portugal were confirmed, and 18 March 2020, when the first state of emergency was declared. It is composed of a total of 306 news reports, broadcasted in the lunchtime (153 reports) and prime time (153 reports) information blocks;

The second involves the evening news blocks of the generalist channels RTP1 (Telejornal), SIC (Jornal da Noite), TVI (Jornal das 8) and CMTV (CM Jornal 20H), during the period in which the first phase of the state of emergency was in effect, between 18 March and 2 March 2020, and the subsequent lockdown was easing cycle, from 3 March to 31 May 2021. In this set, among the four television channels, 900 news reports about the pandemic were codified, corresponding to 75 days, 75 news services and 225 reports per channel.

Given the volume of information, the methodological choice fell on collecting the reports relating to the first three news about covid-19, irrespective of their position in the line-up and their journalistic genre. Even though the two sets of reports are not comparable - the first covers three television channels while the second covers four, in addition to the fact that the analysis covered different news blocks - they constitute valuable material for assessing the changes in communication processes and trends of the journalistic coverage of the pandemic.

Previously cited studies on journalistic attention to epidemics constitute the grounds for the empirical work. The quantitative methodology involved setting up a database in Excel and extracting outputs concerning predefined categories. This procedure enabled the recording, numerical processing of manifest content and extraction of indicators capable of supporting replicable and objective inferences of the substance of the message(s) to understand the observed phenomena. On this basis, a content analysis was performed; this research technique applies to all media and aims at the systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content (Cunha & Peixinho, 2020). The analysis aims at data objectivity and systematisation to point out indicators that allow for its generalisation in similar contexts (Bauer & Gaskell, 2002). The sequence involved a pre-analysis stage and the subsequent consolidation of categories, grounded in the pre-analysis and a literature review, which were parametrised in Excel. The results will enable a reflection on the television coverage of an exceptional event, such as the pandemic.

Thus, based on the literature and a comparative perspective between the two sets of news reports - with a caveat concerning the channels that were analysed and the time period -, the aim was to find a reply to the following questions: (a) which themes concerning the pandemic had greater visibility; (b) which protagonists in the political and health areas were more salient; (c) which settings were allocated to the pandemic. For this study, a subcorpus composed of the news reports focusing on the most frequent covid-19 themes was also set up, looking for signs of contamination of the journalistic coverage by the discourse of the government and health authorities. A second subcorpus was drawn, in which the protagonists are the medical commentators. This made it possible to identify in greater detail the areas of specialisation, the institutional representation and the level of independence in their contributions.

By replying to these questions, it was possible to observe the trends of the journalistic television coverage and track the communication strategies for the media adopted by the governmental institutions, namely the DGS, and their influence on the journalistic agenda.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. The Period from 2 to 18 March 2020

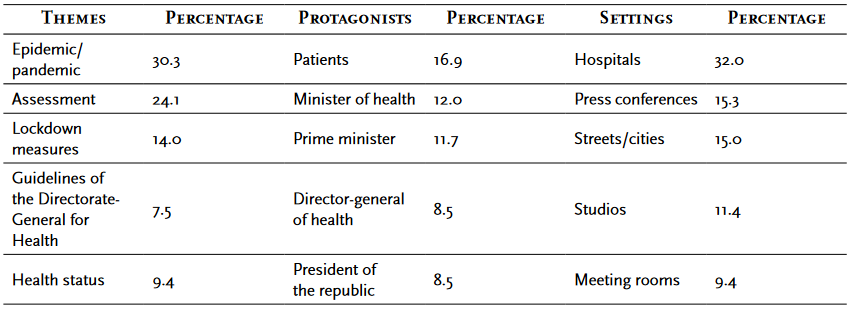

The first three news reports of the line-up about the coronavirus outbreak on the RTP1, SIC and TVI channels tended to favour the themes of “epidemic/pandemic”, “lockdown measures”, “guidelines of the Directorate-General for Health”, and “health status”. Looking deeper into the symbolic associations of the theme “assessment”, it can be seen that those reports were mostly connected with the subtheme “infected”, and specific semantics was used there to describe the various clinical situations and their daily evolution, drawing inspiration from the terminology used by the health authorities in their bulletins: “infected”, “recovered”, “suspected” - a term later abandoned - or “under monitoring” and “deaths”.

The protagonists that stood out were, first and foremost, the patients. These anonymous, faceless figures were the centre of attention, as they represent both the embodiment of the virus and its progression within the community. The minister of health (Marta Temido), the prime minister (António Costa), the director-general of health (Graça Freitas), and the republic president (Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa) also stood out. Thus, in this broader assessment, it was possible to note the protagonism of the political sources of or connected to the government in managing the crisis. The president of the republic was another political protagonist that stood out in terms of the response of the sovereignty bodies to the outbreak and as a subject of self-isolation. In contrast, in the news reports that compose this sample, the parliament and the political parties had barely any expression. Hospitals, press conferences, streets or cities, studios and meeting rooms were the images that most frequently provided a visual frame for the news reports under analysis, constituting “the settings” on the three television channels (Table 1).

Table 1: Top 5 themes, protagonists and settings of the first three news reports about the pandemic broadcasted in the afternoon and evening news blocks of RTP1, SIC and TVI - 2 to 18 March 2020 (%)

Note. N = 306 (total number of news reports analysed in the afternoon and evening information blocks of RTP1, SIC and TVI, between 2 and 18 March 2020)

In this exploratory study, findings were also made as to the growing relevance of anchors, who tended to open their newscasts with emotional and compelling texts while also adopting an educational tone, supporting the guidelines of the DGS about the behaviours that should be adopted in view of the pandemic. Medical and biomedical elements were introduced in the coverage of this theme, aiming at the adoption of preventive and prophylactic behaviours. The story of covid-19 became a social construction on the Portuguese television channels, with several protagonists - authorities, specialists and heroes - and settings, such as press conferences, meeting rooms, studios and hospitals. The collected elements have concluded that the challenge posed by the virus and the pandemic brought the health authorities and mainstream media of Portugal together around the goal of informing, educating and providing guidance to citizens. The creation of the news resorted to a dual routine: the routines specific to television journalism, involving lives, reports, vox pops and archive footage; and those related to the pandemic, from the Ministry of Health and the DGS.

Given the gentleman’s agreement between the DGS and the mainstream media, the health authorities gained a relevant role as gatekeepers, determining the information and the angle of the news, as shown in the themes with greater visibility that were identified. This exploratory study provides evidence suggesting the adherence to the primary definers of information, that is, to how they defined the agenda and framed the problem. The growing limitations to the circulation of journalists, for security and public health reasons, increased their dependence on the events organised by those protagonists from the government or from the sphere of the executive, who controlled the resolution of the crisis, such as meetings and press conferences (Cabrera et al., 2020).

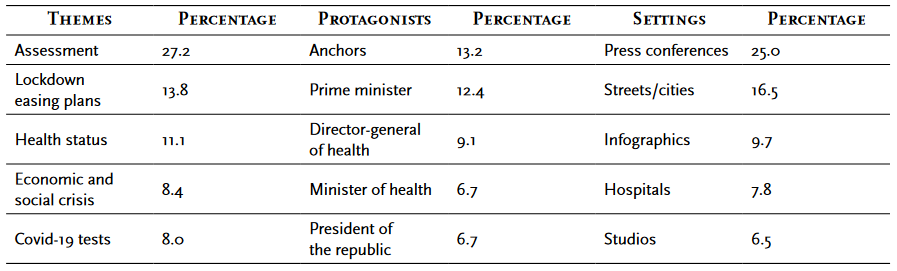

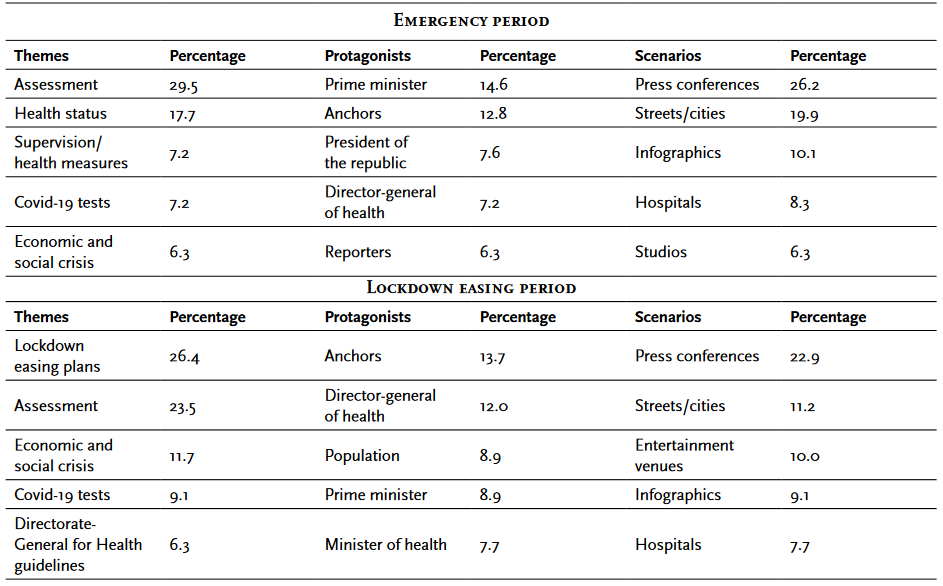

3.2.2. The Period From 18 March to 31 May 2020

In this period, as previously mentioned, the analysis covered the first three reports relating to covid-19 in the prime time news blocks of the channels RTP1, SIC, TVI and CMTV, in a total of 900 news. The aggregated results in themes, protagonists, and settings constitute the specificities of the state of emergency (18 March to 2 May) and the lockdown easing (3 to 31 May). The big picture (Table 2) concerning this data is drawn based on the top 5 themes, protagonists and settings.

Table 2: Top 5 themes, protagonists and settings of the first three news reports about the pandemic in the evening news blocks of RTP1, SIC, TVI and CMTV - 18 March to 31 May 2020 (%)

Note. N = 900 (total number of news reports analysed in the evening information blocks of RTP1, SIC, TVI and CMTV between 18 March and 31 May 2020)

The most relevant themes are the assessments, lockdown easing plans, health status, economic and social crisis and covid-19 tests. The category of the “protagonist” includes, in hierarchical order, the anchors, the prime minister, the director-general of health, the minister of health and the president of the republic. Among the settings, the images of press conferences, streets or cities, infographics, hospitals and studios are dominant.

In an attempt to track the specificities of the journalistic coverage during the emergency and lockdown easing periods, disaggregated data are presented below (Table 3). The emergency period (18 March to 2 May), which accounts for 552 news, shows that there are fewer references to lockdown easing plans and the economic and social crisis, while the five most relevant protagonists are the prime minister, the anchors, the president of the republic, the director-general of health and the reporters.

Table 3: Top 5 themes, protagonists and settings of the first three news reports about the pandemic in the prime time news blocks of RTP1, SIC, TVI and CMTV from 18 March to 2 May 2020 (N = 552) and from 3 to 31 May 2020 (N = 348; %)

Note. N = 900 (total number of reports analysed in the evening information blocks of RTP1, SIC, TVI and CMTV between 18 March and 31 May 2020)

In the lockdown easing period (3 to 31 May), which accounts for 248 reports, we would point out in the top 5 an increase in the news reports about the theme of economic and social crisis and guidelines of the DGS, as well as the appearance of new protagonists, such as the population and the minister of health. Also to be noted is the fact that the anchors gained even more visibility in comparison with the previous period, while the director-general of health and the prime minister became less relevant. Regarding the settings, there are similarities and differences. Among the similarities is the relevance given to images of press conferences, streets or cities and infographics through which the data on the pandemic are presented. The differences appear in the greater use of studios as the setting in the first period analysed and in the use of images of entertainment venues in the second period.

3.3. Discussion and Final Considerations

The strategies adopted by the public health staff and the political authorities involved television as a crucial communication tool. Furthermore, the virus and the pandemic information became highly strategic for the health and political authorities and the television channels. For the health agents and political actors, the use of generalist channels with a bigger audience in Portugal allowed them to publicise and justify their measures, increase public health literacy and mobilise citizens towards compliance with restrictive rules in daily life. At the same time, those same actors ensured that the information transmitted was transparent and correctly explained to influence behaviours, minimize risks, and avoid panic, alarm, and social disruption during the pandemic. By supporting this strategy and becoming the media with more information and greater national demand regarding the pandemic, television channels broke audience records (Cardoso, 2020) and consolidated their brands.

The findings that were made reflect this dynamic, which is attested by the visibility of the themes relating to the assessments, decisions and guidelines about preventive and lockdown measures. While the information on covid-19 became a priority, it is also noticeable that the channels invested in the differentiation of the information offered. That presentation followed the official information from the DGS and included data on geographic distribution, clinical characterisation of the cases (infected, hospitalised, intensive care, recovered, deaths), affected age groups, timeline, the intensity of the transmission and impact of the disease on the National Health Service. Also to be highlighted is the gradual appropriation by anchors, journalists and reporters of the scientific terminology applied to the pandemic to ensure the accuracy of the messages they convey. This effort to incorporate the technical and scientific demands is reflected in the presentation of the data by means of infographics. At the same time, the television stations invested in differentiating their offer through the graphic work in their studios, the originality of the diagrams used in the infographics, the mobilisation of commentators/specialists and the emphasis placed on the role played by the anchors. The goal is to strengthen the brand and specificity of each channel.

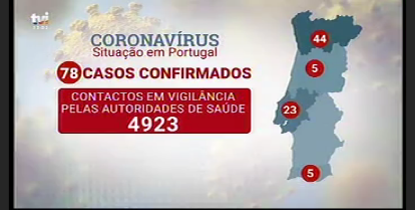

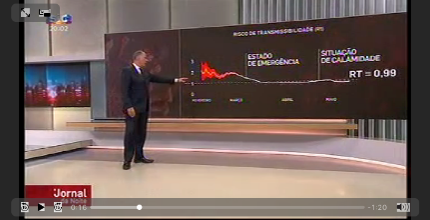

For example, early on, at the beginning of March, as the first cases were recorded in Portugal, RTP1’s infographic (2 March, 2020, 13:02:54; Figure 1) displayed the virus and a test tube. Ten days later, already at 78 confirmed cases in the country, TVI (12 March 2020, 13:01:53; Figure 2) displayed an infographic with the geographical distribution of the infection. In mid-May, a few days before the end of the state of emergency, CMTV (10 May 2020, 20:34:19; Figure 3) presented the total number of infections, deaths, recoveries, cases under examination and admitted to intensive care. Then, at the end of May, already during lockdown easing (28 May 2020, 20:02:08; Figure 4), SIC highlighted the risk of transmission of the disease over time to explain the concept of TR (transmissibility index).

In addition to this branding, health specialists were scheduled to appear as commentators. This is a strategy aimed at adding value to the official information used by all the channels. From a perspective of competing for audiences, the purpose is to have the assistance of a renowned expert who can present his or her knowledge based on good communication with the general public. There are commentators/specialists in all the channels, such as infectious disease specialists, immunologists, public health specialists, epidemiologists, pulmonologists, intensive care physicians, hospital directors in the relevant areas, and health statisticians. The purpose of this strategy was to add more elements and seek alternative sources of information to avoid having news that was limited to the official information and dependent on the primary sources from the government and the commitments with DGS. In this context, the medical specialists became soaring media figures and opinion leaders (Figures 5, 6, 7 and 8).

Source. RTP 1 (13 May 2020, 20:21)

Figure 5: Specialists and physicians become media figures (António Silva Graça, infectious disease specialists)

Source. CMTV (13 May 2020, 21:05)

Figure 6: Specialists and physicians become media figures (Ricardo Batista Leite, infectious disease specialists)

Source. TVI (14 May 2020, 21:04)

Figure 7: Specialists and physicians become media figures (Pedro Simas, virologist)

Source. SIC (20 May 2020, 21:15)

Figure 8: Specialists and physicians become media figures (Ricardo Mexia, public health specialist)

From another point of view, this tendency is also a corollary of the growing importance of health-related communication and journalism, a context in which the literature assesses the value of specialised sources for a news discourse that is more accurate in what it reports and more educational for citizens (Lopes et al., 2020, p. 207).

Along the same line of the brand, strengthening is the choice of the settings that accompany the news, which favours certain images or editing strategies relating to press conferences, streets, cities and hospitals, as well as makes use of aerial footage of hospitals, streets, cities and other places captured by drones. The search for originality and singularity is also present in the use of images from inside the hospitals (hallways, infirmaries, specialised services or health professionals) or of patients in intensive care services, using health professionals to that effect.

A similar process occurred concerning the protagonists of the news. Even though, as previously mentioned, the political actors (prime minister and president of the republic) and health actors (minister of health and director-general of health) gained significant visibility, it is evident that the anchors are the great protagonists. On the one hand, if they take on a dimension inherent to public service - to inform, educate and prevent -, on the other hand, they also strengthen the quality of their branding within the television station in which they work. Anchors become important because they introduce and present the data, the clarity and emotion they bring to their speeches about the pandemic, giving rise to a star system of journalist influencers who draw audiences and guide viewers (Mexia, 2020).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by National Funds through the FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., within the scope of project Ref. UIDB/05021/2020.

REFERENCES

Amaral, V. (2020, 8 de julho). Os 10 países europeus que mais dependem do turismo. Jornal de Notícias. https://www.must.jornaldenegocios.pt/prazeres/lugares/detalhe/os-10-paises-europeus-que-mais-dependem-do-turismo [ Links ]

Bauer, M., & Gaskell., G. (Eds.). (2002). Pesquisa qualitativa com texto, imagem e som. Vozes. [ Links ]

Bourbon, M. J. (2020, 28 de maio). Governo acerta distribuição do apoio pelos grupos de media. Mas mantém Observador e Eco na lista. Expresso. https://expresso.pt/economia/2020-05-28-Governo-acerta-distribuicao-do-apoio-pelos-grupos-de-media.-Mas-mantem-Observador-e-Eco-na-lista [ Links ]

Cabrera, A., Martins, C., & Cunha, I. (2020). A cobertura televisiva da pandemia de covid-19 em Portugal: Um estudo exploratório. Revista Media & Jornalismo, 20(37), 194-201. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_37_10 [ Links ]

Caetano, E. (2020, 6 de abril). França devolve os 4 milhões de máscaras de empresa sueca que tinha confiscado (e que iam para Espanha). Observador. https://observador.pt/2020/04/06/franca-devolve-as-4-milhoes-de-mascaras-de-empresa-sueca-que-tinha-confiscado-e-que-iam-para-espanha/ [ Links ]

Capodanno, J. (2020). Covid-19: Communication strategies for your organization. FTI Consulting. https://www.fticonsulting.com/~/media/Files/us-files/insights/articles/2020/apr/covid-19-communication-strategies-your-organization.pdf [ Links ]

Cardoso, J. A. (2020, 17 de março). Com parte do país em casa, as audiências da televisão são históricas. Público. https://www.publico.pt/2020/03/17/culturaipsilon/noticia/parte-pais-casa-audiencias-televisao-portuguesa-sao-historicas-190820957 [ Links ]

Carlón, M., & Fechine, Y. (Eds.). (2014). O fim da televisão. Confraria do Vento. [ Links ]

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2020). Impact of covid-19 on the media system. Communicative and democratic consequences of news consumption during the outbreak. El profesional de la información, 29(2), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.mar.23 [ Links ]

Cinelli, M., Quattrociocchi, W., Galeazzi, A., Valensise, C. M., Brugnoli, E., Schmidt, A. L., Zola, P., Zollo, F., & Scala, A. (2020). The covid-19 social media infodemic. Sci Rep,10, artigo 16598. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5 [ Links ]

Comissão Europeia. (s.d.-a). Gestão de crises e solidariedade. União Europeia. https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/coronavirus-response/crisis-management-and-solidarity_pt [ Links ]

Comissão Europeia. (s.d.-b). Vacinas seguras contra a covid-19 para os europeus. União Europeia. https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/coronavirus-response/safe-covid-19-vaccines-europeans_pt [ Links ]

Conselho Europeu. (s.d.-a). Combate à desinformação. União Europeia. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/pt/policies/coronavirus/fighting-disinformation/ [ Links ]

Conselho Europeu. (s.d.-b). Pandemia de coronavírus (COVID-19): A resposta da UE. União Europeia. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/pt/policies/coronavirus/ [ Links ]

Correia, A. M., Rodrigues, A. P., Dias, C., Antunes, D., Simões, D. G., Maltez, F., Froes, F., Saldanha, G., Leiras, J., Duarte, G., Magalhães, J. P., Soares, L. M., Tavares, M., Albuquerque, M. J., Brito, M. J., Duque, M. P., Arriaga, M., Pereira, N., Guiomar, R., … Veríssimo, V. C. (2020). Plano nacional de preparação e resposta à doença por novo coronavírus (covid-19). Direção-Geral da Saúde. https://www.dgs.pt/documentos-e-publicacoes/plano-nacional-de-preparacao-e-resposta-para-a-doenca-por-novo-coronavirus-covid-19-pdf.aspx [ Links ]

Cunha, I., & Peixinho, A. T. (2019). Análíse dos media. Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-1988-0 [ Links ]

Direcção-Geral da Saúde. (2020). Coronavírus: Polígrafo e Direção-Geral da Saúde estabelecem parceria contra as “fake news”. República Portuguesa. https://www.dgs.pt/em-destaque/coronavirus-poligrafo-e-direcao-geral-da-saude-estabelecem-parceria-contra-as-fake-news.aspx [ Links ]

Esteves, A. (2020, 26 de junho). “Ainda a gripe espanhola” - Os culpados, as vítimas e a construção da memória. Jornal de Notícias História, 42-51. [ Links ]

EUA são acusados de reter itens médicos destinados a outros países. (2020, 4 de abril). Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/pt-br/eua-s%C3%A3o-acusados-de-reter-itens-m%C3%A9dicos-destinados-a-outros-pa%C3%ADses/a-53014838 [ Links ]

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (s.d.). Covid-19 situation update for the EU/EEA. European Union. Retirado a 1 de maio, 2021, de https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/cases-2019-ncov-eueea [ Links ]

European Institute for Gender Equality. (2020). The covid-19 pandemic and intimate partner violence against women in the EU. https://eige.europa.eu/publications/covid-19-pandemic-and-intimate-partner-violence-against-women-eu [ Links ]

European Union. (2020, 10 de junho). Tackling coronavirus disinformation: getting the facts right. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/corona_fighting_disinformation_0.pdf [ Links ]

Europol. (s.d.). Covid-19: Fake news. European Union. https://www.europol.europa.eu/covid-19/covid-19-fake-news [ Links ]

Figueiras, R. (2021). O que rastreiam as corona-apps? Paradoxos da cultura da vigilância na modernidade digital. In R. Cádima & I. Ferreira (Eds), Perspectivas multidisciplinares da comunicação em contexto de pandemia (pp. 109-125). ICNOVA. [ Links ]

França confiscou dois milhões de máscaras destinadas a Espanha e Itália. (2020, 3 de abril). Zap-aeiou. https://zap.aeiou.pt/franca-milhao-mascaras-espanha-italia-317359 [ Links ]

Freedom House. (2020, 14 de outubro). Report: global internet freedom declines in shadow of pandemic [Press release]. https://freedomhouse.org/article/report-global-internet-freedom-declines-shadow-pandemic [ Links ]

Fujita, M., & Hamaguchi, N. (2020, 16 de agosto). Globalisation and the covid19 pandemic: A spatial economics perspective. Vox. https://voxeu.org/article/globalisation-and-covid-19-pandemic [ Links ]

Georgieva, K., Fabrizio, S., Lim, C. H., & Tavares, M. M. (2020, 21 de julho). The covid-19 gender gap. IMFBlog. https://blogs.imf.org/2020/07/21/the-covid-19-gender-gap/ [ Links ]

Katz, E. (2009). The end of the television? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 625(1), 6-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716209337796 [ Links ]

Kemp, S. (2020, 23 de abril). Digital 2020: April global statshot. DataReportal. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-april-global-statshot [ Links ]

Kemp, S. (2021, 27 de janeiro). Digital 2021: Global overview report. DataReportal. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-global-overview-report [ Links ]

Leiria, I., & Albuquerque, R. (2020, 13 de novembro). A mais longa corrida do século. Expresso, 20-21. [ Links ]

Lopes, F., Araújo, R., Magalhães, O., & Sá, A. (2020). Covid-19: Quando o jornalismo se assume como uma frente de combate à pandemia. In M. Martins & E. Rodrigues (Eds.), A Universidade do Minho em tempos de pandemia: Tomo III: Projeções (pp. 205-233). UMinho Editora. https://doi.org/10.21814/uminho.ed.25.11 [ Links ]

Mexia, D. (2020, 14 de maio). Pivôs de televisão acometidos por um estranho vírus. Dinheiro Vivo. https://www.dinheirovivo.pt/opiniao/pivots-de-telejornais-acometidos-por-um-estranho-virus-12693029.html [ Links ]

Nimmo, B. (2020, 19 de março). Covid-19 and global supply chains: Businesses need to respond to covid-19 supply chains disruption. KPMGBlog. https://home.kpmg/xx/en/blogs/home/posts/2020/03/covid-19-and-global-supply-chains.html [ Links ]

Ogbodo, J. N., Onwe, E. C., Chukwu, J., Nwasum, C. N., Nwakpu, E. S., Nwankwo, S. U., Nwamini, S., Elem, S., & Ogbaeja, N. I. (2020). Communicating health crisis: A content analysis of global media framing of covid-19. Health Promotion Perspectives, 10(3), 257-269. https://doi.org/10.34172/hpp.2020.40 [ Links ]

Ontario Hospital Association. (s.d.). Effective communication strategies for covid-19. https://www.oha.com/news/effective-communication-strategies-for-covid-19 [ Links ]

Organização Mundial da Saúde. (2018). Comunicação de riscos em emergências de saúde pública: Um guia da OMS para políticas e práticas em comunicação de risco de emergência. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259807/9789248550201-por.pdf?ua=1 [ Links ]

Pereirinha, T. (2020, 15 de janeiro). “Não há motivo para alarme”, diz DGS sobre vírus que já fez um morto na China e levou OMS a lançar um alerta global. Observador. https://observador.pt/2020/01/15/nao-ha-motivo-para-alarme-diz-dgs-sobre-virus-que-ja-fez-um-morto-na-china-e-levou-oms-a-lancar-alerta-global/ [ Links ]

Pivots da RTP, SIC, TVI e CMTV juntos a uma só voz contra o covid-19. (2020, 14 de abril). Marketeer. https://marketeer.sapo.pt/pivots-da-rtp-sic-tvi-e-cmtv-junto-a-uma-so-voz-contra-o-covid-19 [ Links ]

Ramos, C., & Jerónimo, P. (2020). Conferências de imprensa da Direção Geral de Saúde no Facebook: Uma análise à interatividade durante a pandemia. In R. Cádima &I. Ferreira (Eds.), Perspectivas multidisciplinares da comunicação em contexto de pandemia (pp. 126-143) ICNOVA. https://doi.org/10.34619/ss2b-cr04 [ Links ]

Reporters Without Borders. (2020). World press freedom index: “Entering a decisive decade for journalism, exacerbated by coronavirus”. https://rsf.org/en/2020-world-press-freedom-index-entering-decisive-decade-journalism-exacerbated-coronavirus [ Links ]

Scannell, P. (2009). The dialect of time and television. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 625(1), 219-235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716209339153 [ Links ]

Soares, M. R. (2020, 2 de outubro). Pandemia amplia desigualdade de género e ameaça “frágeis avanços”. RTP. https://www.rtp.pt/noticias/mundo/pandemia-amplia-desigualdade-de-genero-e-ameaca-frageis-avancos_n1263692 [ Links ]

Stiglitz, J. (2020). Conquering the great divide. The pandemic has laid bare deep divisions, but it’s not too late to change course. FMI: Finance and Development. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/09/COVID19-and-global-inequality-joseph-stiglitz.htm [ Links ]

Thomas, T., Wilson, A., Tonkin, E., Miler, E. R., & Ward, P. R. (2020). How the media places responsibility for the covid19 pandemic - An Australian media analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, Artigo 483. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00483 [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (s.d.). Covid-19 response. https://en.unesco.org/covid19 [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2020). Journalism, press freedom and covid-19. https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/unesco_covid_brief_en.pdf [ Links ]

Vraga, E. K., & Jacobsen, K. H. (2020). Strategies for effective health communication during the coronavirus pandemic and future emerging infectious disease events. World Medical & Health Policy, 12(3), 233-241. https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.359 [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (s.d.-a). Coronavirus disease (covid-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (s.d.-b). Coronavirus disease (covid-19) training: Online training. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/training/online-training#journalist [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2020, 11 de março). WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on covid-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [ Links ]

Yves, J. (2020, 24 de agosto). Study highlights media’s pivotal role in coverage of pandemic health crisis. News Medical Life Sciences. https://www.news-medical.net/news/20200824/Study-highlights-medias-pivotal-role-in-coverage-of-pandemic-health-crisis.aspx [ Links ]

Received: May 17, 2021; Accepted: July 09, 2021

texto em

texto em