Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicação e Sociedade

Print version ISSN 1645-2089On-line version ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.40 Braga Dec. 2021 Epub Dec 20, 2021

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.40(2021).3520

Thematic Articles

Covid-19: A Pandemic Managed by Official Sources Through Political Communication

iCentro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

iiCentro de Investigação em Tecnologias e Serviços de Saúde, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal

A pandemia causada pelo vírus SARS-CoV-2 trouxe para o campo jornalístico um conjunto alargado de especialistas, principalmente da área da saúde. No entanto, as fontes oficiais, sobretudo políticas, não perderam espaço. A elas ficou reservado o papel de decisores, mas isso nem sempre foi comunicado da melhor forma, criando-se com regularidade entropias de vária ordem. Por exemplo, por vezes não se tornou claro por que é que alguns países adotaram confinamentos severos enquanto outros rejeitaram medidas restritivas. A resposta a esta pandemia foi sempre difícil. Acima de tudo, porque o conhecimento era escasso, mas muitas vezes porque não havia cooperação e coordenação entre vários agentes, entre eles os governos, autoridades de saúde ou especialistas. Neste trabalho, procuramos saber qual o lugar das fontes oficiais na imprensa portuguesa durante os estados de emergência. Para isso, analisámos dois jornais, um de referência (Público), outro de linha popular (Jornal de Notícias), de 18 de março a 2 de maio de 2020 e de 9 de novembro a 23 de dezembro de 2020. O nosso corpus de análise é composto por 2.307 textos noticiosos: 1.850 textos foram publicados durante a primeira fase de emergência nacional, citando 4.048 fontes; e 457 foram publicados na segunda fase, apresentando a citação de 857 fontes. Como conclusões, constatamos uma grande visibilidade das fontes oficiais, particularmente do governo, sobressaindo aí o primeiro-ministro e um conjunto restrito de outros ministros. Não há propriamente ninguém que assuma o papel de porta-voz oficial daquilo que vai acontecendo, ao contrário do que é recomendado na literatura, e isso foi provocando alguns deslizes na comunicação ao longo de 2020, verificando-se no final desse ano uma subida de casos, resultante também de algumas hesitações ao nível das decisões.

Palavras-chave: covid-19; jornalismo; fontes oficiais de informação; comunicação de saúde

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic attracted a wide range of expert sources into journalism, especially those from the health field. Nonetheless, official sources (mainly politicians) did not become less visible. They were mainly decision-makers, even though decisions were not always well-communicated, which promoted entropy. Worldwide, countries adopted different strategies, some undergoing severe lockdowns and others rejecting restrictive measures - and that was often difficult to understand. The management of this pandemic was hard, not only due to the lack of technical knowledge but also due to the lack of cooperation and coordination amongst several stakeholders, such as governments, health authorities, or experts. In this research, we seek to understand the role of official sources in the Portuguese press during the emergency states. In order to do so, we analyzed two national newspapers, a reference newspaper (Público) and a mainstream newspaper (Jornal de Notícias) from March 18 to May 2, 2020, and from November 9 to December 23, 2020. Our corpus comprises 2.307 news pieces: 1.850 were published during the first emergency state, quoting 4.048 news sources, and 457 were published during the second emergency state, with 857 sources. We realized that official news sources are highly visible in the news, especially those from the government, such as the prime minister and a few other ministers. Although evidence recommends the appointment of an official spokesperson, that did not happen in Portugal, and it may have contributed to some lapses throughout 2020. By the end of the year, the country had an increase in covid-19 cases, and the hesitancy that characterized political decisions was also behind that.

Keywords: covid-19; journalism; official news sources; health communication

1. Introduction

After some hesitation, on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared covid-19 a pandemic. By then, the new coronavirus had infected more than 118,000 people in 114 countries and caused 4291 deaths. The first death from SARS-CoV-2 occurred in China on January 10, 2020. On January 24, 2020, the coronavirus reached Europe. Portugal reported the first two people infected on March 2, 2020. On March 12, 2020, the Portuguese government announced that, in 4 days, it would suspend face-to-face activities from nurseries to higher education, limit access to shopping centers and public services, reduce the occupancy of restaurants, close bars and ban visits to nursing homes. Later that day, the prime minister stated in a press conference that this was a “struggle for survival and to protect the lives of the Portuguese” (Mendes, 2020, para. 4). On March 14, the weekly newspaper Sol chose for its headline a phrase that was beginning to circulate in the public space: “stay at home”. The headline quickly became a hashtag that the media would constantly replicate: in the top corner of television screens, on their websites, on newspaper pages, in radio line-ups. On March 18, the president of the republic decreed a state of emergency for 15 days, renewed on April 2 and 17. Until May 2, the country lived in confinement, always reported by the news media, which directed citizens to preventive behavior against the disease, seeking to act as a front to fight the pandemic. The state of emergency would resume on November 9, 2020. The speed of the virus intensified, the newsworthiness decreased. However, throughout the year, journalism was always giving great prominence to the pandemic, changing themes, sources, focus, work rhythms, access channels to information sources. However, a variable has remained constant: the importance of official sources, particularly the political ones and, within these, the government.

This paper analyzes how official sources were portrayed by the Portuguese press during the states of emergency decreed in 2020. To do so, we analyzed two newspapers, a reference newspaper (Público) and a mainstream newspaper (Jornal de Notícias) from March 18 to May 2, 2020, and from November 9 to December 23, 2020. The purpose is to know which sources spoke the most and what topics required this type of sources the most. Therefore, we have established a corpus of analysis of 2,307 news texts: 1,850 published during the first stage of national emergency, quoting 4,048 sources, and 457 published during the second stage, incorporating 857 sources.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Importance of Health Communication in Pandemic Contexts

In the context of a public health emergency, the emergence of new risks for populations generates high levels of uncertainty (Reynolds & Seeger, 2005, p. 44). In these circumstances, communication inevitably takes on an enormous centrality. Several authors acknowledge the importance of health communication as an indispensable weapon in fighting against the covid-19 pandemic (Fielding, 2020; Finset et al., 2020). Indeed, the pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus has seriously tested political leaders’ leadership and communication skills worldwide (McGuire et al., 2020, p. 361). Political and health authorities have often failed to communicate decisions effectively. The disparity of responses at the political level, as a whole, is one of the factors that, admittedly, can raise uncertainty among the population. In effect, “uncertainty in the face of health threats scares people, and novel threats such as covid-19 maximize the perception of uncertainty in several ways” (Dunwoody, 2020, p. 472). In this sense, it has not always been clear why certain countries have adopted very strict confinements while others have been reluctant to impose restrictive measures - and this lack of clarity has often been due to communication problems. Don Nutbeam (2020) even acknowledges that “these are challenging times to be in government” (para. 1). “Many governments stuttered at the start of the pandemic, and were slow to provide clarity and certainty. When clarity and consistency of message was missing, people turned to alternative sources of information in the mainstream and digital media” (Nutbeam, 2020, para. 2).

New Zealand is considered a global success story in covid-19 management, and communication skills are an essential aspect of New Zealand’s political leadership (McGuire et al., 2020). “Guiding an effective response to the global pandemic has required leaders to demonstrate not only effective planning and coordination skills, but the ability to communicate clear consistent messages in an empathetic manner as well” (McGuire et al., 2020, p. 361). In addition to communication skills, the response to the pandemic was also largely dependent on “public trust in government information and unprecedented compliance with advice” that dictated the need for personal distancing and hand hygiene (Nutbeam, 2020, para. 1). The effective promotion of covid-19 preventive behaviors relies heavily on communication with the public. It is necessary to communicate what to do and why - and messages should be based on fundamental principles such as clarity, honesty, consistency, and repetition (Finset et al., 2020; Noar & Austin, 2020; Vraga & Jacobsen, 2020), and delivered by credible, non-political sources (Noar & Austin, 2020). Communication to the public must be constantly updated. If there is no new information, the opportunity should be taken to recall what is already known (Ratzan, Gostin, et al., 2020), namely the importance of maintaining a safe distance, breathing etiquette, and mask use where appropriate. Health authorities must recognize the temporality of the messages they convey since, given the rapid evolution of the pandemic, what is true today may not be true tomorrow (Finset et al., 2020). Health authorities should acknowledge this uncertainty about the virus and provide information based on the most up-to-date scientific evidence. That is because hope-based rather than fact-based communication leads to “confusion” and “mistrust” in institutions (Fielding, 2020). In addition to safeguarding these aspects, the number of spokespersons should also be limited and consistent (Finset et al., 2020). “Having a clear voice within government helps avoid a ‘talking heads’ dynamic that undermines the development of a cohesive strategy” (Ratzan, Sommarivac, & Rauh, 2020, para. 10). When countries did not choose a spokesperson, the media and the public itself took care of that (Ratzan, Sommarivac, & Rauh, 2020). Indeed, “the way that officials, leaders, and experts talk with the public during this crisis matters because it could mean the difference between life and death”, as communicational differences between politicians and scientists often result in contradictory, confusing messages and dangerous behavior (Fielding, 2020, para. 1).

That said, political leaders and health experts are more responsible for providing accurate information and implementing measures promoting behavior change (Finset et al., 2020). The response to this pandemic requires cooperation and coordination among various actors, including governments, media, technology platforms, and the private sector (Ratzan, Gostin, et al., 2020).

Maintaining the fragile consensus between governments, their scientific advisers, and their citizens is critical to the successful control of the epidemic. This consensus will be sustained by mutual trust built on effective communication - between scientists and policy makers, and between governments and their populations. (Nutbeam, 2020, para. 6)

2.2. When Official Sources Do Political Communication and Not Health Communication

The covid-19 pandemic has shaken the reliability of the modus operandi of communication management from official sources. Health communication must address many particular traits to be effective (Finset et al., 2020; Noar & Austin, 2020; Vraga & Jacobsen, 2020). This reality becomes more acute when we face a scenario of risk and uncertainty, like the one we have been experiencing since the beginning of 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020). In other words, governments and health authorities should have used the most modern state of the art in health communication and even risk communication in the current framework (Araújo, 2020). However, in this regard, official sources may have failed. Not because they failed to provide the public with the information needed to modulate their behavior to prevent the disease, but because they did not abandon the communicative dynamics typical of political communication, which undermined some of the communication efforts undertaken by creating unnecessary entropies (Martins, 2020).

Official sources tend to dominate the public space through their influence on newsrooms (Araújo, 2017; Fernández-Sande et al., 2020; Gans, 1979/2004; F. Lopes et al., 2011; Magalhães, 2012; Ribeiro, 2006; R. Santos, 1997). Because of its communicative proactivity and the circumstances that shape - and often restrain - journalistic work (Fernández-Sande et al., 2020; Reich, 2011; Van Hout et al., 2011). The value of that hegemony is incalculable. Whoever speaks in the news space defines what reaches society and influences how public opinion interprets information (Fernández-Sande et al., 2020). Hence, it is easy to infer the strategic value arising from the occupation of the media space by political agents, who have been monetizing this reality for decades, creating a “closed circle” between themselves and journalists that silences broad sectors of society (Pérez Curiel et al., 2015).

However, the pandemic challenged the status quo. The reality that has hit the world in 2020 does not match the usual political rhetoric, often empty of content. Journalists have exerted enormous pressure in a relentless search for answers, and official sources have not always been able to respond in the best way to successive requests. This is because the temptation to maintain a political communication logic was strong. Official sources did not know how to share the stage with the experts, naming one as the spokesperson. The daily two-headed press conferences, attended by the director-general of health and the minister of health, were political moments. And even the frequent meetings with the experts (known in the media as “Infarmed meetings”) have relegated scientists to the role of technical information presenters, without a more active - or at least closer - participation in political decision-making, with an exception only in the second confinement plan, initiated in stages from March 15, 2021 (Anjos, 2021; Monteiro, 2021). At the end of the meetings, the political forces were listened to by the media, which lined up in front of the microphones, following their traditional practices carried over from parliament, and replicated pre-packaged political speeches.

Against this background, and in light of the political objectives that traditionally dictate the government-related official sources’ communication strategies, one can see that the pandemic represented an outstanding risk at the beginning of 2020. However, it was also an excellent opportunity to strengthen the reputation of a minority government, whose stability in power depends on the prime minister’s political skill, the position of the left-wing parties in parliament, and friendly relations with the president of the republic. In addition, the “micro agendas” of different official sources were still evident, which tried to gain the most advantageous possible media positioning at each moment of the pandemic. The problem is that, in trying to capitalize politically on gains in the war against covid-19, official sources have contaminated the public debate around the pandemic. If they have managed to reap political dividends (SIC Notícias, 2020), at times, they have been easy targets at other times (P. Santos, 2020). Moreover, in the process, communication has lost quality.

3. Empirical Study

3.1. Methodological Paths

“In this pandemic time, which summons specialized knowledge, what place did official sources hold in the Portuguese press?” That initial concern motivated this research, which is part of a broader project that seeks to determine how the generalist news media in Portugal covered the covid-19 pandemic. To address this objective, we conducted a quantitative analysis of the news about covid-19 published in two national daily newspapers, a reference newspaper (Público) and a popular line newspaper (Jornal de Notícias). We chose two specific periods: March 18 to May 2, 2020, and November 9 to December 23, 2020. Those dates are related to periods when Portugal has declared a state of emergency during the year 2020. The digital print versions of the newspapers were used to collect the data. When selecting cases, we considered all the news texts published in the newspaper sections entitled “Primeiro Plano” (Forefront; Jornal de Notícias) and “Destaque Covid-19” (Covid-19 highlight; Público). According to a previously developed and tested analysis grid, the collected data were processed, coded, and categorized using the statistical analysis program SPSS Statistics.

Focusing our work on information sources, we tried to analyze which type of source journalists use the most; their status and the institution they work for; where they speak from; and their medical specialty, if any. Our analysis corpus consists of 2,307 news texts: 1,850 texts published during the first phase of the national emergency, citing 4,048 sources, and 457 published during the second phase, quoting 857 sources.

This work is part of a broader project that addresses the media coverage of the covid-19 pandemic in the Portuguese press, continuously analyzing the daily newspapers during the states of emergency and trying to find out, through surveys, the perceptions of Portuguese journalists regarding the work developed (F. Lopes et al., 2020).

3.2. Outcomes and Discussion

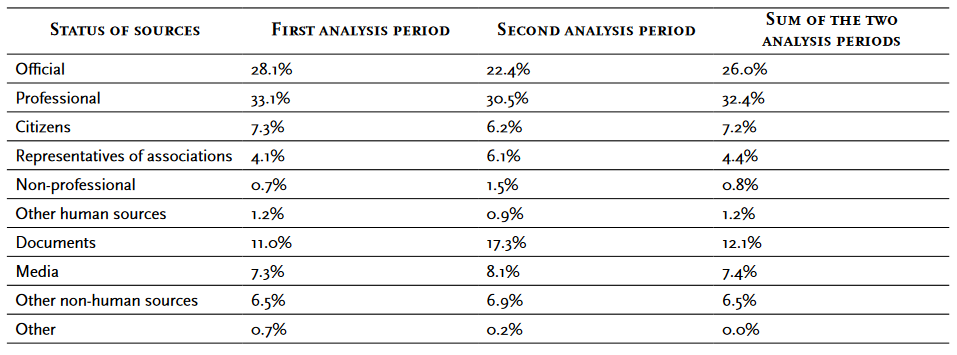

Although professional sources, particularly experts, gained high visibility in the media coverage of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (accounting for more than 30% during the two analyzed periods), official sources were also privileged (26% in both periods). They were more connected to decision processes that proved to be structural in managing the SARS-CoV-2 evolution. When we add official documents (decree-laws, health authority reports, etc.) to the official human sources, the frequency increases to 33.1% in the first wave and 31.3% in the second wave, thus surpassing the influence of specialists in the news texts through this period (33.1% during the first wave and 30.5% in the second wave). We are talking essentially about interlocutors linked to political decision-making centers and power elites, with the government standing out in this group, especially the prime minister, who has taken it upon himself to communicate the most critical measures in managing this pandemic. As shown in Table 1, there is a fair diversity of information sources, although this conjuncture called for more expert knowledge, official interlocutors never ceased to be important in the media arena, namely in the Portuguese press.

Table 1: Status of information sources in the articles published during the two pandemic waves in the Portuguese daily press

Looking at the themes where official sources are quoted the most, one can see that national politics stand out (500 citations), particularly in decision-making (269 citations). Due to its thematic dispersion, society also has a high frequency (305 citations).However, issues related to nursing homes (73 citations), education (66 citations), and justice (25 citations) are more prone to quoting this type of source, namely the ministers responsible for these areas: social solidarity, education, and justice. In third place, we highlight the reports (212 citations), a somewhat broad category, which includes a variety of interlocutors, with the counting of infected and dead people (82 citations) and epidemiological analyses (63 citations) being the topics where official voices are particularly prominent. Ranked fourth is international politics (148 citations), where almost half of the official citations are focused on meetings/decisions (65 citations). The economic themes are also conveyed by quoting a significant number of official sources (130), namely the issues related to the economic crisis (53 citations) where the minister of economy took the lead, often even in the place of the minister of finance. The fields of research and development and service organizations were not approached by official interlocutors, adding 30 and 20 citations, respectively.

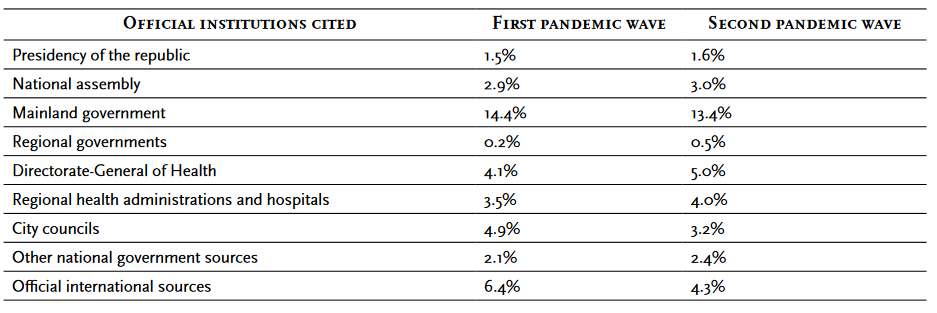

The most relevant official institutions in the journalistic discourse during the pandemic period (Table 2) are the government (central power, representing 14.4% in the first pandemic wave and 13.4% in the second) and local authorities (local power, representing 4.9% in the first wave and 3.2% in the second). The presidency of the republic, despite playing a relevant role in managing the pandemic, did not stand out in 2020 (with a visibility of around 1.5% in the two waves), a period that coincides with the last months of Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa’s first mandate. Nor did the members of parliament have a continuous presence in the daily press, representing around 3% in both periods analyzed. Contrary to what the literature recommends (Finset et al., 2020; Ratzan, Sommarivac, & Rauh, 2020), no one took on the role of official spokesperson for what was happening. Neither did the country have an expert who could be the spokesperson for a team that would advise the government from a scientific background, as happened, for example, in the United Kingdom. In fact, and referring to the two periods of analysis, sometimes this role was played by the director-general of health (2.1%), sometimes by the assistant secretary of state for health, sometimes by the minister of health (1.3%) and sometimes by the prime minister himself (3.1%). This dispersion echoed in the daily press.

Table 2: Official institutions cited in the articles published during the two pandemic waves in the Portuguese daily press

In 2020, Portugal lived in a state of emergency between March 18 and May 2 and between November 9 and December 23. In constitutional terms, this decision presents a shared competence: the president of the republic declares a state of emergency after the government has expressed this will. Parliament must approve the presidential decree allowing for the suspension of rights, liberties, and guarantees. As can be seen, this is a decision that structurally alters the lives of all citizens. However, although throughout 2020 the president of the republic chose to make a formal communication to the country on the day he signed those decrees, the prime minister always took it upon himself to provide a more detailed explanation of that decision, also in spaces organized for that purpose and designed for media coverage.

When the state of emergency was first declared, the media reported that the government had some reservations about the presidency’s willingness to move quickly to exercise a constitutional power that had never been used before. On March 17, 2020, the newspaper Público reported that “Costa and Marcelo disagree on the declaration of a state of emergency” (Almeida & Botelho, 2020), with the executive leaning towards the option of the state of public calamity provided for in the Basic Law on Civil Protection. That gave the prime minister and the minister of home affairs full responsibility for adopting the measures. Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa presided over a Council of State on March 18 at the Palácio de Belém, after prophylactic isolation due to a presidential initiative he attended on March 8, 2020 with a class which had a young student hospitalized for being infected. On that same day, he declared the first state of emergency in Portuguese democracy. The government complied, and parliament approved the decision with no dissenting votes.

In the second wave of the pandemic, from November onwards (and during the pre-campaign and electoral campaign for the presidential elections), Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa recalled several times that he was the one who took that first step towards the state of emergency. However, this advance did not translate into greater visibility for him. Until the end of this first phase of the state of emergency, the president of the republic and the prime minister articulated in a political and regulatory harmony that was more behind-the-scenes than public and, consequently, media-oriented. In this regard, the government has always had a great advantage. From May 3, 2020, the country entered a state of calamity, with the executive assuming the political leadership of the pandemic management in an extensive interpretation of the Basic Law of Civil Protection. The summer saw a slowdown in the containment measures, and by autumn, Portugal began to register an increase in the number of infections and deaths that would lead from November 8 to the second phase of the state of emergency lasted until December 23. Again, there are some hesitations between Belém and São Bento, whose news media’s contours have never quite been explained. On November 2, 2020, Público wrote, “Costa proposes Marcelo a minimal but prolonged state of emergency” (M. Lopes & Botelho, 2020, para. 1). The president of the republic meets again with the parties and social partners to discuss the country’s situation. In an evening interview on RTP1, he assumed supreme responsibility and criticized specific points in the pandemic management. This time, in parliament, the approval of the decision was less consensual. However, the two largest parties, PS and PSD, ensured a large majority for successive renewals of the state of emergency, which soon ceased to be minimal and was even in conjunction with general confinement, from January 15, 2021 (during the campaign for the election of the president of the republic).

In the government, the prime minister always took it upon himself to communicate at delicate moments in the pandemic management, often even making mea culpa of how he conveyed decisions. On November 12 2020, in the second phase of the emergency regime, António Costa, in a press conference, acknowledged that he was not effective in conveying the containment measures adopted for the weekend: “it is all my fault because it was indeed the messenger who got the message wrong. We have to convey a strict rule, and the rule is at 1 p.m. everything is closed” (Gomes & Garcia, 2020, para. 7). On January 13, 2021, announcing the country’s second strict confinement, he said: “here I am showing my face, with no fuss or shame, going back to where we were last April” (Governo da República Portuguesa, 2021, 08:47). Besides the prime minister, who accounts for 3.8% of the sources of information cited during the second pandemic wave, other ministers stood out. In contrast, others were tossed into a spiral of silence. Among the former were the ministers of home affairs, labor, and social security, education, economy, presidency, and health, the latter gaining high visibility (2.4% of the total sources cited). However, this has not always been the case.

In the early days, it was not the holders of the ministry of health who took over communication with the country. It was the director-general of health, Graça Freitas. Daily press conferences were initially only to report suspicious cases, later proved to be unfounded. Under the state of emergency, health officials joined these meetings, adding a political dimension to them. In January 2021, Portugal was considered one of the countries with the highest numbers of infections and deaths. By then, these formats disappeared and were not replaced by any other. In an initiative on the occasion of world cancer day, in Alcochete, on February 4, 2021, the director-general of health said that she does not “need to show up” (Lusa, 2021, para. 2). She needs “to work”, adding that “other communication options were taken” without, however, specifying them (Lusa, 2021, para. 2). Before that, there were other contradictions. On January 15, 2020, with the virus already spreading, Graça Freitas stated that at that time, “this does not represent a recognized threat to public health, i.e., a new virus was identified, but it does not appear to be infectious to humans” (Daniel, 2021, 02:42). A few days later, on January 21, World Health Organization spokesman Tarik Jasarevic said the human-to-human transmission was occurring, and more cases should be expected in other parts of China and possibly in other countries. In a press conference on March 22, 2020, regarding the use of masks, Graça Freitas advocated, “there is no point in using masks (...), they serve almost no purpose. They only give a false sense of security. Don’t wear masks. Be cautious and keep a social distance. That is our appeal” (SNS | Portal do SNS, 2020, 07:56). On April 30, 2020, in a meeting with journalists to explain containment measures adopted in days to come, she said that we must wear masks to go to the shops and use more public transport.

4. Final Remarks

Although the pandemic brought the experts to the center of the journalistic scene, official sources, particularly political ones, never lost prominence. Indeed, the circle of those who should be listened to has been widened. Beyond the always valued role of facts, the relevant information is added, especially with a kind of “wise knowledge” guiding a daily life that has radically changed with this pandemic. To some extent, this has forced official sources to adjust their discourse, making it more of substance and less of rhetoric. At numerous press conferences, governments used scientific reports, visual presentations, and statistics to provide their communications with a scientifically based argumentative narrative that would convince people to adhere to their communicated measures. There was a substantial reduction in the parties’ presence in the public media space in this period. Throughout 2020, party political contention has dramatically diminished, visible in the reduced numbers of party-related sources. Even the parliament has considerably slowed down the newsworthiness it usually provokes. In times of pandemic, the politicians who stood out the most were always the rulers: the prime minister more than his ministers, the ministers more than the secretaries of state, and those from specific areas of governance (health, presidency of the council of ministers, economy, education and labor, and social security).

The prime minister played a leading role in the news texts on covid-19, consistently outranking the president of the republic and the president of the assembly of the republic in media visibility. Also, within the executive, his command was notorious. For the day-to-day management of the disease, the minister of health and the director-general of health were very active players on the media stage. However, when it came to communicating decisions that involved structural changes in the functioning of society (such as confinement or more restrictive measures), the prime minister called upon himself to communicate, never sharing the stage with his minister of health. Thus it symbolized what has always been a social and news media trend: men decide, women execute.

If we focus on the news themes where official sources were quoted the most, we conclude that they converged on the most relevant moments of the pandemic. The 10 topics where official sources appeared most frequently were: political decisions; assessments of the number of deaths and infections; problems affecting nursing homes; medical action in health services; education; international meetings; epidemiological analyses; problems related to the economic crisis; the most salient portraits of the country; and what was happening in the field of justice. Moreover, this also reflected what stood out from the news point of view. This trend gradually replaced specialized sources with official ones. Both took on a much of prominence. Nevertheless, the official sources were deciding; the specialized ones explained, making the former more important.

The political communication of these interlocutors was not always the most concerted and articulate. Having never appointed a team of scientists throughout 2020 to assist it in decisions and without an official spokesperson permanently, the government has been communicating decisions through a variety of interlocutors: prime minister, minister of health, director-general of health, secretaries of state of health, and a few officials. Throughout 2020, the director-general of health held press conferences, always flanked by government officials, and it was not clear whether the meetings with journalists were technical or political. Also, the frequency oscillated, from daily to only a few days a week, eventually disappearing from January 2021, paradoxically just when the pandemic reached the most severe rates worldwide. That suggests that there was never really a well-designed communication strategy to communicate with citizens. Rather than official sources, it was journalists who were most consistent in promoting the news of this pandemic. Furthermore, if official sources managed to quickly control the numbers of infections and deaths in the first wave, deciding quickly and communicating this clearly, throughout 2020, hesitations on these two levels increased. So did the severity of the disease. That was no coincidence.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under project UIDB/00736/2020 (base funding) and UIDP/00736/2020 (programmatic funding) and within the scope of the contract signed under the transitional provision laid down in article 23 of Decree-Law no. 57/2016, of August 29, as amended by Law no. 57/2017, of July 19.

REFERENCES

Almeida, S. J., & Botelho, L. (2020, 17 de março). Costa e Marcelo discordam sobre declaração de estado de emergência. Público. https://www.publico.pt/2020/03/17/politica/noticia/costa-prefere-estado-emergencia-tarde-1907984 [ Links ]

Anjos, M. (2021, 25 de fevereiro). Ainda não deu para perceber que as reuniões do Infarmed não funcionam? Visão. https://visao.sapo.pt/opiniao/ponto-de-vista/em-sincronizacao/2021-02-25-ainda-nao-deu-para-perceber-que-as-reunioes-do-infarmed-nao-funcionam/ [ Links ]

Araújo, R. (2017). Dinâmicas de construção do noticiário de saúde: Uma análise da imprensa generalista portuguesa [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade do Minho]. RepositóriUM. http://hdl.handle.net/1822/45761 [ Links ]

Araújo, R. (2020, 3 de julho). Correr atrás do prejuízo. Público. https://www.publico.pt/2020/07/03/opiniao/opiniao/correr-atras-prejuizo-1922850 [ Links ]

Daniel, C. (Anfitrião). (2021, 2 de fevereiro). Comunicar em pandemia (Temporada 2, Episódio 2) [Programa de televisão]. In É ou não é? - O grande debate. https://www.rtp.pt/play/p8396/e522038/e-ou-nao-e-o-grande-debate [ Links ]

Dunwoody, S. (2020). Science journalism and pandemic uncertainty. Media and Communication, 8(2), 471-474. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i2.3224 [ Links ]

Fernández-Sande, M., Chagas, L., & Kischinhevsky, M. (2020). Dependence and passivity in the selection of information sources in radio journalism in Spain. Revista Espanola de Documentacion Cientifica, 43(3), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.3989/redc.2020.3.1712 [ Links ]

Fielding, J. (2020, 31 de março). Good communication will help beat covid-19. The Hill. https://thehill.com/opinion/healthcare/490410-good-communications-will-help-beat-covid-19 [ Links ]

Finset, A., Bosworth H., Butow P., Gulbrandsen, P., Hulsman, R. L., Pieterse, A. H., Street, R., Tschoetschel, R., & Van Weert, J. (2020). Effective health communication - A key factor in fighting the covid-19 pandemic. Patient Education and Counseling, 103(5), 873-876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.03.027 [ Links ]

Gans, H. J. (2004). Deciding what’s news: A study of CBS evening news, NBC nightly news, Newsweek, and Time. Northwestern University Press. (Trabalho original publicado em 1979) [ Links ]

Gomes, H., & Garcia, F. (2020, 12 de novembro). Covid-19. Costa reconhece falhas na comunicação: “A culpa é toda minha”. Concelhos de alto risco passam a ser 191. Expresso. https://expresso.pt/politica/2020-11-12-Covid-19.-Costa-reconhece-falhas-na-comunicacao-A-culpa-e-toda-minha.-Concelhos-de-alto-risco-passam-a-ser-191 [ Links ]

Governo da República Portuguesa. (2021, 13 de janeiro). Conferência de imprensa do Conselho de Ministros, 13 de janeiro de 2021. República Portuguesa, XXII Governo. https://www.portugal.gov.pt/pt/gc22/comunicacao/multimedia?m=v&i=conferencia-de-imprensa-do-conselho-de-ministros-13-de-janeiro-de-2021 [ Links ]

Lopes, F., Ruão, T., Marinho, S., & Araújo, R. (2011). Jornalismo de saúde e fontes de informação, uma análise dos jornais portugueses entre 2008 e 2010. Derecho a Comunicar - Revista Científica de La Associación de Derecho a La Información, (2), 101-120. http://132.248.9.34/hevila/Derechoacomunicar/2011/no2/6.pdf [ Links ]

Lopes, F., Araújo, R., Magalhães, O., & Sá, A. (2020). Covid-19: Quando o jornalismo se assume como uma frente de combate à pandemia. In M. Martins & E. Rodrigues (Eds.), A Universidade do Minho em tempos de pandemia: Tomo III: Projeções (pp. 205-233). UMinho Editora. https://doi.org/10.21814/uminho.ed.25.11 [ Links ]

Lopes, M., & Botelho, L. (2020, 2 de novembro). Costa propõe a Marcelo estado de emergência mínimo e prolongado. Público. https://www.publico.pt/2020/11/02/politica/noticia/costa-propoe-marcelo-estado-emergencia-minimo-prolongado-1937626 [ Links ]

Lusa. (2021, 4 de fevereiro). Covid-19. Graça Freitas justifica “desaparecimento” com nova estratégia de comunicação. Expresso. https://expresso.pt/coronavirus/2021-02-04-Covid-19.-Graca-Freitas-justifica-desaparecimento-com-nova-estrategia-de-comunicacao [ Links ]

Magalhães, O. E. (2012). Comunicação de saúde e fontes - O caso da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade do Porto]. Repositório Aberto. https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/66407 [ Links ]

Martins, R. (2020, 10 de novembro). O que falhou na comunicação da pandemia? Público. https://www.publico.pt/2020/11/10/sociedade/noticia/falhou-comunicacao-pandemia-1938580 [ Links ]

McGuire, D., Cunningham, J. E. A., Reynolds, K., & Matthews-Smith, G. (2020). Beating the virus: An examination of the crisis communication approach taken by New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern during the covid-19 pandemic. Human Resource Development International, 23(4), 361-379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2020.1779543 [ Links ]

Mendes, F. A. (2020, 12 de março). “Manda a prudência que determinemos a suspensão de todas as actividades lectivas presenciais”. Público. https://www.publico.pt/2020/03/12/politica/noticia/manda-prudencia-determinemos-suspensao-actividades-lectivas-presenciais-1907549 [ Links ]

Monteiro, L. (2021, 23 de fevereiro). “Reuniões do Infarmed são um faz de conta que se ouve a ciência”. Renascença. https://rr.sapo.pt/2021/02/23/pais/reunioes-do-infarmed-sao-um-faz-de-conta-que-se-ouve-a-ciencia/noticia/227760/ [ Links ]

Noar, S. M., & Austin, L. (2020). (Mis)communicating about covid-19: Insights from health and crisis communication. Health Communication, 35(14), 1735-1739,https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1838093 [ Links ]

Nutbeam, D. (2020). Covid-19: Lessons in risk communication and public trust. Public Health Research & Practice, 30(2), Artigo e3022006. https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp3022006 [ Links ]

Pérez Curiel, C., Gutiérrez Rubio, D., Sánchez González, T., & Zurbano Berenguer, B. (2015). El uso de fuentes periodísticas en las secciones de política, economía y cultura en el periodismo de proximidad español. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico, 21(0), 101-117. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_esmp.2015.v21.50661 [ Links ]

Ratzan, S. C., Gostin, L.O., Meshkati, N., Rabin, K., & Parker, R. (2020). Covid-19: An urgent call for coordinated, trusted sources to tell everyone what they need to know and do.NAM Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.31478/202003a [ Links ]

Ratzan, S. C., Sommarivac, S., & Rauh, L. (2020). Enhancing global health communication during a crisis: Lessons from the covid-19 pandemic. Public Health Research & Practice, 30(2), Artigo e3022010. https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp3022010 [ Links ]

Reich, Z. (2011). Source credibility and journalism. Journalism Practice, 5(1), 51-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512781003760519 [ Links ]

Reynolds, B., & Seeger, M. W. (2005). Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. Journal of Health Communication, 10(1), 43-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730590904571 [ Links ]

Ribeiro, V. (2006). Fontes sofisticadas de informação: Análise do produto jornalístico político da imprensa nacional diária de 1995 a 2005 [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade do Porto]. Repositório Aberto. http://hdl.handle.net/10216/13047 [ Links ]

Santos, P. C. dos. (2020, 23 de novembro). A comunicação em saúde no contexto da pandemia: Quando tudo serve para arma de arremesso político. Expresso. https://expresso.pt/opiniao/2020-11-23-A-Comunicacao-em-Saude-no-contexto-da-pandemia-quando-tudo-serve-para-arma-de-arremesso-politico [ Links ]

Santos, R. (1997). A negociação entre jornalistas e fontes. Minerva. [ Links ]

SIC Notícias. (2020, 9 de abril). Portugal é considerado um exemplo de boas práticas no combate à pandemia de covid-19. SIC Notícias. https://sicnoticias.pt/especiais/coronavirus/2020-04-09-Portugal-e-considerado-um-exemplo-de-boas-praticas-no-combate-a-pandemia-de-Covid-19 [ Links ]

SNS | Portal do SNS. (2020, 22 de março). 22/03/2020 | Conferência de imprensa covid-19 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HaTa97ccZKc [ Links ]

Van Hout, T., Pander Maat, H., & De Preter, W. (2011). Writing from news sources: The case of Apple TV. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(7), 1876-1889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.09.024 [ Links ]

Vraga, E. K., & Jacobsen, K. H. (2020). Strategies for effective health communication during the coronavirus pandemic and future emerging infectious disease events. World Medical & Health Policy, 12(3), 233-241. https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.359 [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2020). Covid-19: Global risk communication and community engagement strategy. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/covid-19-global-risk-communication-and-community-engagement-strategy [ Links ]

Received: July 29, 2021; Accepted: August 12, 2021

text in

text in