Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicação e Sociedade

Print version ISSN 1645-2089On-line version ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.39 Braga June 2021 Epub June 30, 2021

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.39(2021).2879

Thematic Articles

Media Strategies of Labor Platforms: Circulation of Meanings in Social Media of Companies in Brazil

iLaboratório de Pesquisa DigiLabour, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Comunicação, Universidade do Vale do Rio do Sinos, São Leopoldo, Brazil

iiCentro de Pesquisa em Comunicação e Trabalho, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Comunicação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Este artigo tem o objetivo de analisar como as plataformas de entrega e transporte no Brasil construíram seu ethos nas mídias sociais, no contexto da primeira greve dos trabalhadores dessas empresas, dentro do cenário da pandemia de coronavírus. Argumentamos, a partir da noção de circulação de sentidos, como a construção do ethos das plataformas é um elemento sígnico da luta de classes e uma dimensão do papel da comunicação na plataformização do trabalho. Conduzimos análise do conteúdo veiculado em mídias sociais (Instagram, Facebook, Twitter e YouTube) de duas plataformas de entrega (iFood e Rappi) e duas de transporte (Uber e 99), as principais do país. As categorias de análise são: “pandemia e saúde” (dimensão contextual em relação à crise sanitária); “cidadania e diversidade” (dimensão recorrente no discurso produzido pelas plataformas, em linha com a literatura da área), “relações com marcas e influenciadores” (trabalho de visibilidade das plataformas com públicos interessados específicos) e “representações dos trabalhadores” (como elemento central da dimensão sígnica da luta de classes). Em linhas gerais, as estratégias de comunicação das plataformas, focadas nos consumidores, apresentam sentidos de caridade, filantropia, cidadania e diversidade, dizendo-se abertas às demandas dos trabalhadores. As reivindicações dos trabalhadores são ressignificadas a partir de um olhar de cidadania sacrificial, autoajuda, empreendedorismo e superação. Os resultados mostram como a comunicação das plataformas nas mídias sociais jogam um papel central nas contradições de classes.

Palavras-chave: Brasil; circulação de sentidos; comunicação; trabalho em plataformas

This article aims to analyze how ride-hailing and delivery platforms in Brazil produce their ethos on social media in the context of the first national strike of workers in the pandemic. We argue, based on the notion of circulation of meanings, how the construction of the platform’s ethos is a sign element of class struggles, and a dimension of the role of communication in the platformization of labor. We conducted a content analysis on social media (Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube) from two delivery (iFood and Rappi) and two ride-hailing platforms (Uber and 99), the largest of the country. The categories are: “pandemic and health” (contextual dimension in relation to the pandemic); “citizenship and diversity” (recurrent dimension in the discourse of platforms, in line with the literature in the area), “relations with brands and influencers” (visibility labor of the platforms with specific stakeholders) and “workers’ representations” (as a central element of the sign dimension of the class struggles). In general, the platforms’ media strategies, focused on consumers, present meanings of charity, philanthropy, citizenship and diversity, stating they are open to the demands of workers. The workers’ demands are reframed from the perspective of sacrificial citizenship, self-help, entrepreneurship and resilience. The results show how the platforms’ media strategies on social media play a central role in class contradictions.

Keywords: Brazil; circulation of meanings; communication; platform labor

Introduction

Research on platform labor has emerged in recent years (Casilli, 2019; van Doorn, 2017). However, communication is still an underrepresented element in the area. On the one hand, there are studies, such as Mosco (2009) and Figaro (2018), which point out how work and communication are interconnected, but without referring exclusively to digital platforms. On the other hand, there is research on platform labor that highlights the role of social media in the organization of workers (Cant, 2019; Lazar et al., 2020) and the rhetoric behind the so-called “sharing economy” (Codagnone et al., 2016). However, there is no systematic examination about the centrality of communication for platform labor.

We argue that communication plays a central role in the platformization of labor (Casilli & Posada, 2019), as a way of organizing - in the sense of Sodré (2019) - both for the workers’ control, surveillance and management, and for the organization of workers and construction of worker-owned platforms. Communication works across the entire circuit of platform labor (Qiu et al., 2014) from their infrastructures and materialities to consumption practices.

Platforms, in addition to digital infrastructures supplied by data and automated by algorithms (Srnicek, 2016; van Dijck et al., 2018), act as means of production and communication (Williams, 2005), which engender ways of work and interaction. Their materialities provide the technical bases for the organization of work (Plantin et al., 2018; Woodcock & Graham, 2019) and are designed for some interactions to the detriment of others (Costanza-Chock, 2020; Wajcman 2019). Based on their affordances, there are politics around digital platforms to dismantle communication between workers and facilitate the worker-consumer relationship (Popescu et al., 2018; Wood & Monahan, 2019).

The mechanisms of workers’ surveillance, data collection and extraction (Couldry & Mejias, 2019), as well as algorithmic management, operate not only within the platforms but also through processes of consumption itself (as a communication process), either as “customer” - nomenclature commonly used by platforms - or “worker”. That is, data policies and algorithmic mediations operate from communication processes.

Communication is also central to the organization of platform workers, whether in unions and associations, in emerging collectivities and solidarities or in the construction of worker-owned platforms (Scholz, 2016; Soriano & Cabañes, 2020; Wood et al., 2018), as elements of the circulation of workers’ struggles (Dyer-Witheford et al., 2019; Englert et al., 2020). This shows that workers do not passively accept the production and communication contexts of the platforms but create strategies and tactics for their everyday work (Cant, 2019; Sun, 2019).

Thus, we can summarize the place of communication at platform labor from the following vantage points: (a) designs and materialities of the platforms; (b) work organization and management; (c) organization of workers, as formal and informal spaces; (d) data and algorithm policies; (e) consumption of platforms; and (f) platforms’ media strategies.

Based on these elements, this article focuses on the media strategies of platforms as one of the dimensions of the role of communication in platform labor. The background is that there is a dispute over control of the meanings about what the platforms mean - including work and workers. This struggle for meanings occurs within the scope of communication throughout the circuit of labor (Qiu at al., 2014), but finds, in the platforms’ discourses, a privileged place for analysis.

Thus, the article highlights the notion of “circulation of meanings” in Silverstone (1999) to investigate, in a specific way, how platforms build communication and media (therefore social and discursive) worlds about themselves. The ethos (Maingueneau, 2001) is an expression of this circulation of meanings. For example, platforms use strategies such as advertising and public relations campaigns to circulate brand meanings across different social fields. Moreover, they intend to control the meanings of the public debate regarding labor platforms. Their discourses circulate with some values and meanings to the detriment of others, as symbolic expressions of class struggles (Grohmann, 2018). This theoretical framework allows us to understand the ideological clashes and disputes around the meanings (Baccega, 1995; Voloshinov, 1973) built in the world of work (Figaro, 2018), as opposed to theoretical perspectives that start from the place of the company or the brand as neutral.

In addition, the circulation of meanings is the basis of economic support for these platforms. In other words, signs circulate as a form of capital (Goux, 1973; Marazzi, 2011; Rossi-Landi, 1973). Thus, the circulation of discourses is an indication of the role of communication in financialization (Sodré, 2019) and in the mechanisms of rentism (Sadowski, 2020).

So, media strategies of the platforms work as forms of justification, sedimentation and crystallization of positive meanings of the platforms, building imaginaries in line with a neoliberal and entrepreneurial rationality (Dardot & Laval, 2013) and with the Silicon Valley ideology (Liu, 2020; Schradie, 2015). Thus, they intend to persuade workers and consumers that they are innovative, disruptive and socially responsible companies. Expressions such as “gig economy” and “sharing economy” are also part of this circulation of meanings and are traces of a corporate platform capitalism (Frenken & Schor, 2017; Pasquale, 2016; Scholz, 2016; Srnicek, 2016). These dominant narratives also claim that platforms have no ties to workers and that they are only mediators who help workers - according to the literature on the issue (Dubal, 2019; Gibbings & Taylor, 2019; Karatzogianni & Matthews, 2020; Rosenblat, 2018). The literature on media strategies of platforms in the so-called “global south”, especially Latin America, is still underrepresented. This does not mean, however, that these strategies are unique, as they are connected to a geopolitics of platforms (Graham & Anwar, 2019) and subsumed in the Silicon Valley ideology, which presents colonial features (Atanasoski & Vora, 2019; Couldry & Mejias, 2019; Liu, 2020).

This article aims to analyze how delivery and ride-hailing platforms in Brazil have built their ethos on social media, as media strategies, in the context of the first Brazilian strike of the workers within the scenario of the pandemic. The construction of the platform’s ethos - and their ways of producing and circulating meanings - is a symbolic element of class struggle and, at the same time, a dimension of the role of communication in the platform labor (Grohmann, 2018; Silverstone, 1999).

We conducted a content analysis on social media (Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube) - as a privileged locus of circulation of meanings - from two delivery (iFood and Rappi) and two ride-hailing platforms (Uber and 99), the main ones in Brazil. Our hypothesis considered that the communication presented by these companies prioritizes broader sectors of society (especially consumers), whereas the dialogue between platforms and their workers is rarefied, except to posit the value of the platform itself.

The analytical categories are: “pandemic and health” (contextual dimension in relation to the health crisis); “citizenship and diversity” (recurrent dimension in the discourse produced by the platforms, in line with the literature review); “relations with brands and influencers” (visibility work of the platforms with specific interested audiences); and “workers’ representations” (as a central element of the sign dimension of class struggles). Platforms’ media strategies, focused on consumers, present meanings of charity, philanthropy, citizenship and diversity, saying they are open to the demands of workers. The results show how the communication of platforms on social media play a central role in class contradictions as their sign dimension in the context of the platformization of labor.

Context and Methodology

The working conditions of drivers and delivery workers have similar characteristics in various parts of the world, as evidenced in the research by “Fairwork” (2019). However, countries in the global north have specificities, as they have historically had the minimum consolidation of a welfare state and regular employment (Huws, 2020). The so-called “global south” is not a deviation from the standard, but is itself what constitutes a standard and norm in global economies (Alacovska & Gill, 2019; Chen & Qiu, 2019; Graham, 2019; Sun, 2019; Wood et al., 2018). This means historically locating and contextualizing both the countries of the north and those of the south - which also have many heterogeneities among them. What the platform labor has in common in the global south are the legacy of the informal economy and the contradictions surrounding their post-colonial condition, with its revolutionary potentials and regressive pitfalls (Grohmann & Qiu, 2020).

In these terms, platform labor presents: (a) a generalization of the typical work of the peripheries of the world to the global north, with a subordination to the platform oligopolies (Abílio et al., 2020); (b) for the global south, the new is not the gig or the precarity of work, as they have historically been the norm, as a permanent way of life for the working class. The novelty is precisely the dependence on digital platforms to ensure workers’ survival (Grohmann & Qiu, 2020).

Latin America also presents heterogeneities in relation to the most used platforms and regulatory issues (Cordero & Daza, 2020). Brazil is an example of this scenario of platformization of labor, presenting about 23% of the worldwide users of Uber, which arrived in the country in 2014 (Amorim & Moda, 2020). In 2019, approximately 4,000,000 Brazilians work for the main platforms in the country - Uber, 99, iFood, and Rappi (Amorim & Moda, 2020).

Delivery workers, in general, earn less than $200 a month and are typically Brazilians, blacks and young people (Aliança Bike, 2019), highlighting the intersections between class and race that are historical in the country. The pandemic has accelerated the platformization process, with increasing reliance on platforms for livelihood. In March 2020, the number of orders on food delivery platforms grew by 77% in the country, but riders are working harder and earning less, with more competition (Abílio et al., 2020). In some way, the pandemic contributed to the visibility of these workers, as they support people who are in social isolation.

In this scenario, riders and drivers are more exposed to the risks of being contaminated by covid-19. In an analysis of the policies of 123 platforms in 22 countries during the pandemic, a report from the “Fairwork” project (2020) points out a contradiction between the views of platforms and workers. Platforms say they are communicating all measures to workers, such as the distribution of personal protective equipment. However, from the viewpoint of workers, the promises did not come true. Many had to pay for personal protection products and were denied claims for sickness benefits (Howson et al., 2020). Researchers at “Fairwork” (2020) point out that, at best, platforms are slow to adopt emergency measures and, at worst, are more concerned with public relations strategies and consumers rather than workers.

In Brazil, even more precarious working conditions added to the exposure of risks and the visibility of these workers as essential workforce during the pandemic, which helped in the organization of delivery workers to mobilize two national strikes during July 2020 (1st and 25th of July). They were the biggest labor strikes in the country in the last decade, with self-organization of workers mainly by social media, in a country of continental dimensions. The main demands were increased pay, an end to unfair blockages and the scoring system, as well as adequate provision of personal protective equipment without workers having to pay for it. Riders also appealed to the solidarity of consumers, asking them not to order anything from the platforms in the days of strikes (Abílio et al., 2021).

This is the background for the analysis we conducted on media strategies of four ride-hailing and delivery platforms in Brazil. The context of a pandemic and workers’ strike has placed platforms under public scrutiny when they felt compelled to intensify their media strategies, as a symbolic dimension of class struggles. According to Abílio et al. (2021), there was a change in news coverage between the first and the second strike of delivery workers. Legacy media started to use data and views of the platforms to the detriment of the workers’ perspective. The context of platform labor in Brazil contradicts, on the one hand, the viewpoint of workers, according to the scenario described above, and, on the other hand, the viewpoint of platforms, which aims to control public discourse through the meanings that they circulate about themselves.

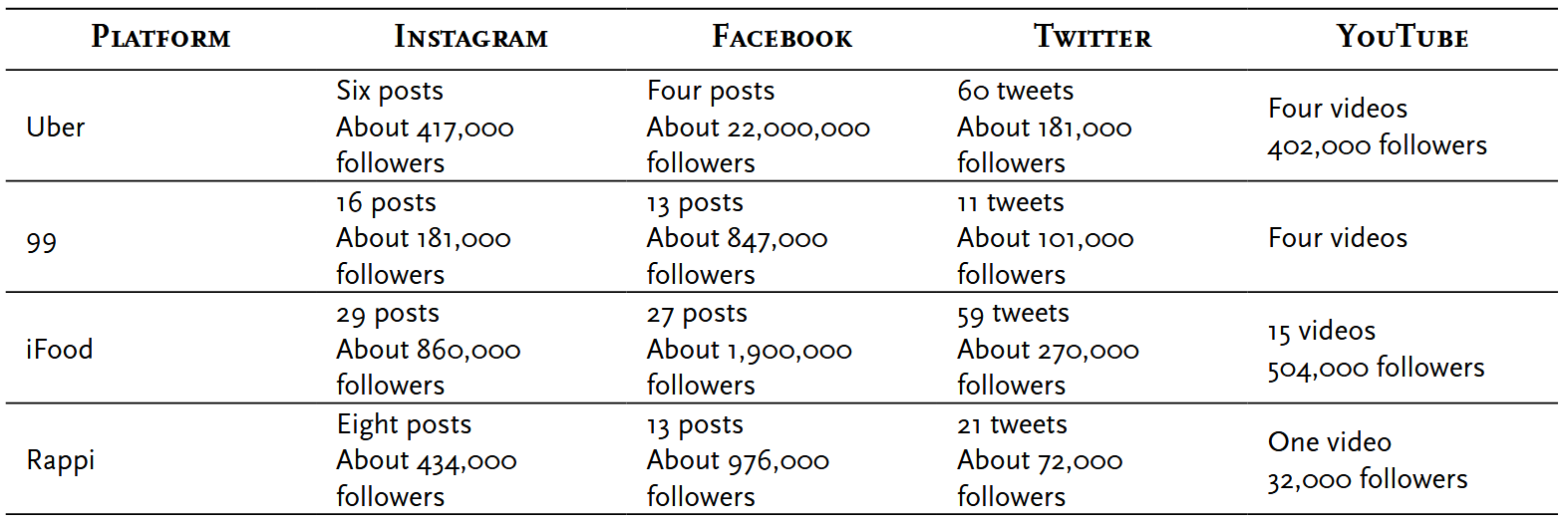

Based on this, we conducted a content analysis of communication from four platforms (Uber, 99, iFood, and Rappi) from Brazilian accounts2 on the following social media - Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube - between June 15 and August 15, 2020, a period justified by the context of strikes and pandemics. Social media accounts were chosen because they have become spaces par excellence for visibility and circulation of meanings in the context of platformization (Leaver et al., 2020; Poell et al., 2019). That is, social media are central to the platforms’ media strategies, in the sense of promoting and circulating their brands positively (Scolere et al., 2018), that is, their ethos. In addition to the specific materialities of each platform (Bucher & Helmond, 2018), we argue that ethos - and the platforms’ media strategies - circulate their meanings through different social media, which are a privileged locus for the circulation of meanings. We also emphasize that the media strategies of platforms are not limited to social media and that there are other possibilities not analyzed in this research, such as journalistic pieces and official pages, for example. The corpus is introduced in Table 1.

At first, we observed irregularities between the different platforms and their uses of social media. Of all platforms, iFood is the one that has used social media the most. While Uber, iFood and Rappi made more posts on Twitter, 99 mainly used Instagram. This irregularity also happens temporally on each platform. iFood, for example, the biggest target of delivery strikes, intensified its publications in July, but after the first week of August, it spent weeks without any post. Rappi has not posted on August on Instagram and Uber has not updated his Facebook page since June 2020.

Of the four platforms, only Uber can be considered, from the beginning, as a global platform. Headquartered in San Francisco, it is present in 69 countries and arrived in Brazil in 2014. 99 was created in 2012 by three Brazilian entrepreneurs and, initially, intended to only mediate contact between taxi drivers and passengers. Then it became an Uber competitor. In 2018, the company was sold to the Chinese DiDi (Chen & Qiu, 2019), the world leader in the segment. In the delivery sector, iFood is a leader in Brazil, where it was founded in 2011. Currently, it has a presence in other countries in Latin America, such as Mexico, Argentina, and Colombia. Rappi was founded in 2015 in Colombia and arrived in Brazil in 2017. It promises to deliver not only food, but anything that the consumer asks for, including documents. They are the main platforms in the delivery and ride-hailing sectors in Brazil, which reveals an origin mainly in the global south, specifically in Latin America. However, this does not mean that media strategies of these platforms are very different from those based in the north, as they are shaped by colonial ideologies and linked to platforms in the United States (Atanasoski & Vora, 2019; Davis & Xiao, 2021).

Results

Media strategies of the platforms in a period are threads that present historicity, which is not a novel subject (Bakhtin, 1979). As an example, the platforms’ websites - which are not in our corpus - are evidence of how the meanings of the platforms circulate, presenting themselves as citizen brands, with social responsibility and purpose. Uber (n.d.) highlights “global citizenship”. 99 (n.d.), on the other hand, presents itself as a data-driven company that values diversity. Rappi claims that its “partners” work “with love” (https://www.rappi.com.br/). This attribute is also highlighted by iFood (n.d.): “passion for food and technology”. In addition to these elements, corporate communication is generally focused on the consumer, for example, Rappi states “an app that is revolutionizing the way that Brazilians do their purchases” (https://www.rappi.com.br/).

Specifically, the corpus of the research reveals that the meanings of the platforms circulate through the different media simultaneously. We chose four categories from the corpus, with the circulation of meanings of platforms on social media as a backdrop. The first category - “health and pandemic” - is contextual and refers to the context of the global health crisis. The second - “citizenship and diversity” - is at the center of corporate strategies: the values of citizenship and diversity, as discursive elements of platforms with social purpose and for the common good, in line with research that analyzes narratives and entrepreneurial rationality (Casaqui & Riegel, 2016).

The last two categories involve relationships and representations with specific stakeholders. On the one hand, influencers and other brands help to circulate the values of the platforms and to circulate meanings of credibility, as a visibility work (Abidin, 2016). On the other hand, workers’ representations on the platforms are part of the significant dimension of class struggles, with regimes of visibility and invisibility (Hall, 1997), in order to gain the adhesion of workers and public opinion.

Health and Pandemic

In the first category, Uber adopted the slogan “no mask, no ride”. This campaign can be found similarly in other countries, with the same text in English. In Brazil, specifically, the platform incorporated the maxim “Uber security standard” to encourage the association of an imaginary that assumes the “Uber standard” as a synonym for quality standard. It extends this understanding to the security and protection that the company offers in the context of a pandemic. In a video letter published on Twitter on July 8, 2020, the company claims to be “investing more than R$250,000,000 to supply masks, cleaning services, and cleaning products for the cars of partner drivers around the world”.

99 and iFood also said they were putting all their efforts together to protect workers from risks in relation to covid-19. This included disclosing that it distributed masks and alcohol gel, as well as donating races to healthcare professionals. 99 also announced car hygiene actions in media strategies focused on the consumer: “more than ever, protecting you is a priority for us. The result? 1.5 million safer races at no extra cost to you! Count on us whenever you need to feel even more secure”. Rappi, meanwhile, did not comment on the pandemic between June and August 2020 in its social media accounts.

In general, the worker has no voice in the communication on pandemic and health issues, in which companies prioritize numbers and measures taken. The “Fairwork” (2020) report on covid-19 shows that media strategies on the pandemic are very similar around the world, as well as workers’ claims regarding personal protective equipment, one of the central points of the strike among delivery workers in Brazil (Howson et al., 2020).

Citizenship and Diversity

During the period of analysis, platforms celebrated LGBTQIA+ pride day. Uber presented meanings against prejudice, rescuing precepts that had already been highlighted in the Brazilian carnival of the same year, when a campaign to reinforce respect was launched by Uber and, according to information from the platform’s official website (Uber, 2020), aimed to disclose its code of conduct. Rappi conducted an advertising campaign in partnership with a beer brand in which the orders went with a flag of the LGBTQIA+ cause as a gift. The amounts were donated to a non-governmental organization. The campaign’s slogan was: “celebrate diversity wherever you are. Decorate your window and show your pride”.

Donations were also present in media strategies of 99: “we donated R$4 million in races so that governments from all over Brazil can use in the transportation of those who cannot stop in the pandemic. Our partner drivers receive 100% of the value of these races”. In this case, the context of the pandemic is used to reaffirm the meanings of citizenship, in the context of austerity policies (Brown, 2016).

This scenario is also part of the ethos built by Uber, which sponsored the “Leisure Cycle Track” initiative in the city of São Paulo. In a post on Twitter on July 18, there is a photograph of a person riding a bicycle and wearing a mask. It presents the following message: “do you want to cycle again in São Paulo? Uber takes you”. According to a director of the platform in Brazil, “the so-called new normal is an opportunity for all of us, who live in São Paulo, to rethink our relationship with the automobile and how it affects our city”. In this way, the platform’s communication presents meanings of environmental sustainability and health. This is in line with a neoliberal city model in which platforms seek to intervene in urban spaces from a business perspective (Morozov & Bria, 2018).

Another example of this private reappropriation of citizenship and the public good is iFood, which spoke through its policy director days before the delivery strike in Brazil: “delivery platforms, public authorities and riders must be co-responsible and co-creators of the new order. IFood is available”. The platform promotes itself as a benefactor for society as a whole, producing meanings of social responsibility.

In relation to diversity, platform 99 has endeavored to include different racial, ethnic, gender and class profiles in the advertisements of its accounts on social media. A post, published on June 17 by the philosopher Djamila Ribeiro, caused controversy because of a sponsored post made for 99. She is known for her advocacy around the defense of black women, has 1,000,000 followers on Instagram, and was considered by BBC one of the 100 most influential women in the world. In the video, the philosopher narrates her experience in using the platform and highlights “the protection packages” that the company adopted during the pandemic and also the “social responsibility” by offering free disinfection of cars to drivers.

The sponsored post caused surprise and outrage among her followers and among activists of social and racial movements because it was done at a time when platform workers - the majority Black (Abílio et al., 2020) - were organizing themselves publicly and requesting better working conditions. In addition, it occurred in the context of racial protests in the United States over the death of George Floyd, brutally murdered by police officers.

During the video, the philosopher adopts the same expressions used by the platforms to address drivers, naming them “partner drivers” and “collaborators”, a strategy used by platforms in their communication processes as evidence of the significant dimension of class struggles (Grohmann, 2018). By naming drivers as “partners” and highlighting the “social role of the company”, there is an attempt at closeness that hides informal and precarious work on platforms, especially in a country like Brazil (Abílio et al., 2020). The presence of a publicly recognized figure for being on the side of minorities, such as Djamila Ribeiro, reinforces the reputation and credibility as values in circulation of the platforms. 99 wanted to strengthen the image of a socially responsible company, using in advertising a representative respected by the Black community. However, it does not recognize the working relationship with riders (Abílio et al., 2020).

The struggle against racism, verbalized by 99 with the presence of Djamila Ribeiro, was also used by Rappi. After a case of racism by a customer with a delivery worker, which took place on August 7, the platform cited its competitors, such as iFood, on Twitter:

I believe that you must have followed the case of rider Matheus, who suffered a crime of racism. We checked and he is not registered on our platform. Can you help us find it so we can support and take action on the user?

With this, the platform reinforces the meanings of platform directed to the common good.

The meanings of citizenship and diversity are related to that of union, as stated by iFood’s marketing director:

this movement of diversity is very punctuated by the context we are in now. As a brand, we have an obligation to bring this message of unity and not of polarization. When we look more at the consumer it would end up being natural.

This statement reinforces that media strategies are directed to the consumer and with meanings of diversity. The “union”, linked to social responsibility, is placed as an opposition to the “polarization”, in the sense of the Brazilian political context. Thus, the platform naturalizes class struggles and sees itself as the leader of unity in society.

Relationships With Brands and Influencers

Platform partnerships with brands and influencers reinforce the place of enunciation directed at consumers. All Rappi statements, for example, about diversity are in partnerships with other brands. 99 has already invested in posts by influencers with young profiles, from different Brazilian capitals, and of various genres, which maintains between 50 and 150,000 followers on its pages, to publicize new products, such as 99 Delivery and campaigns, such as #99Mobilize. The posts are usually repeated on various social media, but the preference is on Instagram. The most constant phrase on the platform’s pages is: “the starting point of 99 is people”. And that motto translates into the posts, which are usually directed to consumers, treated directly by “you”.

The 99 statements reinforce meanings of entrepreneurship as the best way out of the financial crisis or unemployment, in line with neoliberal rationality (Dardot & Laval, 2013) and with research on rhetoric in the platform economy (Codagnone et al., 2016). An example is the post about driver Mary Stela published simultaneously on Instagram and Twitter:

when Mary Stela realized it was time to start over. She rented a car and went on to better days as a partner driver 99. And isn’t it that it worked so well that she became a highlight in the national ranking of drivers?!

The discourse reinforces the intersection of the discourse of entrepreneurship with the meanings of overcoming and self-help, something that was already common in communication strategies of companies outside the work platform, as evidenced by Illouz (2007) and Castellano (2018).

What 99 presents as different is that autonomy and flexibility can only happen with “help” from the platform, as a relationship of trust: “it has achieved more than that: financial independence, flexibility to enjoy the family and more confidence to work with the supports that 99 has been offering in recent months”. In other words, the incentive to entrepreneurship is related to social change based on working on platforms, as in the phrase “being a partner 99 is the opportunity that can change your life”.

If, in the previous categories, on “health”, “diversity and citizenship”, the platforms’ media strategies reinforce the sense of social responsibility, the posts with brands and influencers reveal the tonic in the discourse of entrepreneurship as an individual way out and towards flexibility and autonomy. There is a cross between the categories, as the entrepreneurial discourse is related to social change and confidence in the platforms.

Among the platforms analyzed, Rappi is the one with the least posts on citizenship, health and safety of workers. The platform did not make any posts about the pandemic or mention of the delivery workers’ strike. Its focus is strictly on the consumer market and it is the platform with the most posts in partnerships with brands: “now you buy in one click and receive it in minutes. You find several brands of clothing, electronics, beauty, toys, and much more”. One of the highlights is the videos with make-up with the following statements: “running out of mascara at the time of make-up doesn’t work, right?”. The platform’s Twitter still features several memes circulating in Brazilian digital culture.

Workers’ Representation

Rappi’s media strategies in relation to workers are primarily on the YouTube channel, Rappi Entregador. The channel represents the worker either as someone in debt or as the target of citizenship and social responsibility actions, with no place for claims. Work issues remain invisible and the dominant meanings are close to what Wendy Brown (2016) calls “sacrificial citizenship”. Some statements are: “how to pay your debts and how to open a claim if you do not recognize the debt”, “hello delivery partner! Do you already know how to settle your debts with Rappi?”. In this way, the worker is trapped in a circuit of long working hours and debts as a worker-consumer of the platform (Huws, 2014). These mechanisms have occurred in Brazil since before the platformization of labor, as shown by Abílio (2015) in the cosmetics sector.

At Uber, worker representations are complex and contradictory. First, the worker is positioned as a user of the platform’s services, in a relationship between platform and consumer, just like the logic of the consumer’s work stated above. In this rhetoric, on the one hand, drivers, as worker-consumers, benefit from one of the platform’s products, meaning the possibility of generating income. On the other hand, the consumer of the platform benefits from the service of facilitating mobility in urban spaces. On the YouTube channel, a video to present the “Uber safety standard”, lists the new rules and recommendations that both drivers and passengers must follow, dialoguing with both audiences indistinctly, as mere users of the offered digital services.

A second image positions the driver as a service provider, which reveals more clearly the ambiguity of the working relationship established in the relationship with the platform. In a post on Twitter on July 24, the page celebrates Driver’s Day and presents the #EstrelaExtra campaign that elects outstanding drivers and presents their personal reports accompanied by name and photo: “tomorrow is Driver’s Day [red heart emoji] Partner drivers, in addition to taking passengers to their destinations, are also protagonists of attitudes that improve other people’s lives. These stories deserve to be shared: #ExtraStar #DriversDay”.

Neoliberal rationality is embodied in stars as a way of ranking and classifying workers (Dardot & Laval, 2013). Workers’ surveillance is translated as a meaning of improvement for the platform. The driver, victim of the impacts of the health and economic crisis, is represented as a beneficiary of charitable initiatives. In addition, the platform starts to encourage tipping as a way for consumers to achieve their individual social improvement. Thus, platforms circulate meanings of sacrificial citizenship (Brown, 2016).

iFood, in turn, represents itself as an open brand for workers and their demands, being the most active platform during the delivery workers’ strike. The director of public policies at the platform said that workers earn more and feel happier at work than academic research says. He also said that “manifesting is a right for everyone, including partners”, and that, therefore, there was no deactivation of delivery workers participating in the strike. The text was published in a national newspaper in Brazil and on the platform’s Twitter.

Another initiative by iFood was the video “place your order on the iFood App” published on YouTube. Based on the text “you already noticed with one delivery leads to another”, the platform sought to share the responsibility with consumers in relation to the demands of the delivery workers. In the ad, the platform treats the numbers centrally and highlights the 25,000,000 it has earmarked for prevention measures and which doubled each amount paid by the customer in tips. As in other statements, tipping is an indication of sacrificial citizenship, as a substitute for the best working conditions for delivery workers.

Another iFood project is “Opening the Kitchen”. This expression is used as a synonym for transparency and is part of the vocabulary of restaurants that show the entire process of food preparation. This project was used by the platform as a defense of the company amid strikes by couriers in Brazil. There is even a section with frequently asked questions about the strike. Some topics are part of the agreement between the platform and the workers, for example, “how delivery workers operate via iFood” or “how the delivery value is calculated”. In a post on Instagram, the platform states: “we do not block delivery workers for participating in strikes. We understand it as a right of our partners. Unfair blocking, no!”. This statement presents interdiscursivity with the workers’ claims against unfair blocks. The media strategy of platforms is presented as if it were on the same side as the worker sharing similarities with discourses of protests and social movements, thus the platform presents itself as sensitive to the demands of workers.

After the strikes, the platform published a new campaign called #LivingIsADelivery. The use of the hashtag indicates that the advertising campaign was produced to circulate on social media and the word “delivery” is the element of continuity in other campaigns of the platform, such as #OurDelivery. The meanings of the word “delivery” detach themselves from the figure of the worker for life, in line with the narratives about purpose and self-help (Castellano, 2018).

The campaign consists of six audiovisual pieces with different themes. They are love, sweetness, family, friendship, courage and responsibility. In the video with the theme “friendship”, unlike previous campaigns, there is no image of consumers receiving food with agility and convenience. The advertising piece features two men, one Black, who plays the role of delivery worker and restaurant owner. In the sentimental conversation, they describe a food delivery scene in which one recognizes the other. They were friends from school who met at that moment. The Black man was the owner of the restaurant. The other was the delivery worker.

In addition to humanizing the company, representing it as a community of friends, the play addresses the racial issue precisely at the time when demonstrations against the genocide of the Black population were taking place in several countries. This is in line with the campaign previously analyzed from 99 with the philosopher Djamila Ribeiro. Thus, there is the reappropriation of racial and workers’ meanings in favor of platforms, which represent themselves as citizens.

With the same sentimental tone, another advertising piece portrays a delivery worker who is a mother and her son is proud to see her going out to work everyday “not only to guarantee everyday bread, but to deliver food to other families”. The video ends by praising the qualities of the woman: “a woman’s life is never giving up and a mother’s life is always surrendering”. The meanings are of thanks to the platform because the character was unemployed and started working as a delivery worker to be able to pay for the financing of a motorcycle. Thus, the dominant meanings are those of thanking the platform for promoting social good and that of individual satisfaction that the delivery workers have a noble mission in relation to society as a whole and should be grateful for that. Thus, there is the re-semantization of a worker in search of the rights for a citizen who must sacrifice himself for the common good - which, in this case, means the discursive perspective of the platforms.

Therefore, workers’ representations vary between someone invisible, indebted, grateful for the opportunity and who must sacrifice himself for the benefit of society. Even when the worker is the center of media strategies, his voice appears only to maintain the viewpoint of the platforms and their commercial strategies. The demands for better working conditions are represented as “polarization” and the platforms symbolize “union”, shifting the word “delivery” from the worker to something abstract.

Conclusions

Media strategies of platforms in their accounts on social media are only one aspect of the communication of these companies - among other possibilities of circulation of meanings. And this discursive dimension is just a role of communication in platform labor, from design to consumption, in a circuit of labor. The platforms’ discourses present historicizations and go beyond the period chosen for this corpus. Social media accounts represent a synthesis of how meanings circulate on platforms, in order to reassemble and crystallize meanings about the digital economy, consumers and workers.

The results show that, on the one hand, platforms present specificities in their designs, worker profiles and working conditions, according to Schor et al. (2020), their media strategies across different sectors, with similar narratives and discourses. The choice of two areas (ride-hailing and delivery) resulted in more similarities than differences between the discursive positions of the platforms. This is also due to the ideological circulation of platforms in various countries around the world, in line with colonial values and linked to Silicon Valley ideology. Thus, the article argues that media strategies of the platforms can meet local specificities, but their meanings tend to circulate internationally.

The analytical categories - “health and pandemic”, “citizenship and diversity”, “relations with brands and influencers”, and “workers’ representations” - proved to be less exclusive than complementary to each other. The core of the platforms’ media strategies is to position themselves as citizen companies, linked to diversity, the common good, the purpose of the social good, in favor of unity and not of polarization, with social responsibility. This happens in different dimensions. Imaginaries promoted by their discourses - of citizenship, diversity, and social responsibility - place platforms as central agents for the whole well-being of society. The idea that working is an opportunity is in line with many workers’ discourses in the global south (Wood et al., 2019). These meanings can be an indication, for future research, in the discourses of other platforms in the global south, with potential for generalization, given the strength of its circulation.

The discourses on health and pandemic are the context of the circulation of the meanings of the platforms - showing that platforms’ initiatives are being made to mitigate the effects of covid-19 in society. The relations with brands and influencers, in turn, point to the ways in which platforms direct their discourses to consumers. From the partnerships, they show themselves as versatile companies and concerned with the practicality of consumers. It is in this context in which social and protest agendas begin to be re-signified and re-semanticized by the platforms, in order to neutralize social struggles and show themselves as leaders of a discursive universality.

In the category of “workers’ representation”, collective claims are reframed from the perspective of sacrificial citizenship, self-help, entrepreneurship and overcoming. At a certain moment, they can even pretend to be at the workers’ side, as in the statement “unjust blocking, no”. Discourses like those of a public policy director - a position aligned with neoliberal rationality and its application in urban spaces - about the platform being open to workers’ demands are common in order to show themselves as reliable companies to consumers.

Workers are made invisible, represented as indebted, people with dreams, but not as workers and, mainly, as a working class. Thus, from the class composition framework (Cant, 2019), platforms aim to neutralize the political composition of the working class based on their media strategies, constructing imaginaries of what ideal workers and consumers would look like, in a circuit of platform labor. This reinforces our argument that the platforms’ media strategies are a significant dimension of class struggles. If platform labor is a laboratory for class struggles, communication is at the core of these struggles.

Referências

Abidin, C. (2016). Visibility labour: Engaging with influencers’ fashion brands and #OOTD advertorial campaigns on Instagram. Media International Australia, 161(1), 86-100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X16665177 [ Links ]

Abílio, L. (2015). Sem maquiagem: O trabalho de um milhão de revendedoras de cosméticos. Boitempo. [ Links ]

Abílio, L., Almeida, P., Amorim, H., Cardoso, A. C., Fonseca, V., Kalil, R., & Machado, S. (2020). Condições de trabalho de entregadores via plataforma digital durante a covid-19. Revista Jurídica Trabalho e Desenvolvimento Humano, 3, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.33239/rjtdh.v.74 [ Links ]

Abílio, L., Grohmann, R., & Weiss, H. (2021). Struggles of delivery workers in Brazil: Working conditions and collective organization during the pandemic. Journal of Labor and Society. Publicação eletrónica antecipada. https://doi.org/10.1163/24714607-bja10012 [ Links ]

Alacovska, A., & Gill, R. (2019). De-westernizing creative labour studies: The informality of creative work from an ex-centric perspective. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(2), 195-212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877918821231 [ Links ]

Aliança Bike. (2019). Pesquisa de perfil de entregadores ciclistas de aplicativo. https://aliancabike.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/relatorio_s2.pdf [ Links ]

Amorim, H., & Moda, F. (2020). Work by app: Algorithmic management and working conditions of Uber drivers in Brazil. Work Organisation, Labour & Globalisation, 14(1), 101-118. https://doi.org/10.13169/workorgalaboglob.14.1.0101 [ Links ]

Atanasoski, N., & Vora, K. (2019). Surrogate humanity: Race, robots, and the politics of technological futures. Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Baccega, M. (1995). Palavra e discurso: História e literatura. Ática. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. (1979). The aesthetics of verbal art. Iskusstvo. [ Links ]

Brown, W. (2016). Sacrificial citizenship: Neoliberalism, human capital, and austerity politics. Constellations, 23(1), 3-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12166 [ Links ]

Bucher, T., & Helmond, A. (2018). The affordances of social media platforms. Sage handbook of social media. Sage. [ Links ]

Cant, C. (2019). Riding for deliveroo: Resistance in the new economy. John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Casaqui, V., & Riegel, V. (2016). Management of happiness, production of affects and the spirit of capitalism: International narratives of transformation from Coca-Cola brand. The Journal of International Communication, 22(2), 293-314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13216597.2016.1194304 [ Links ]

Casilli, A. (2019). En attendant les robots: Enquête sur le travail du clic. Seuil. [ Links ]

Casilli, A., & Posada, J. (2019). The platformization of labor and society. In. M. Graham & W. Dutton (Eds.), Society and the internet: How networks of information and communication are changing our lives (pp. 293-306). Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Castellano, M. (2018). Vencedores e fracassados: O imperativo do sucesso na cultura da autoajuda. Appris. [ Links ]

Chen, J. Y., & Qiu, J. L. (2019). Digital utility: Datafication, regulation, labor, and Didi’s platformization of urban transport in China. Chinese Journal of Communication, 12(3), 274-289. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2019.1614964 [ Links ]

Codagnone, C., Karatzogianni, A., & Matthews, J. (2016). Platform economics: Rhetoric and reality in the ‘sharing economy’. Emerald Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781787438095 [ Links ]

Cordero, K., & Daza, C. (2020). Precarización laboral em plataformas digitales: Una lectura desde América Latina. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Ecuador FES-ILDIS. [ Links ]

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice. MIT Press. [ Links ]

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. A. (2019). Data colonialism: Rethinking big data’s relation to the contemporary subject. Television & New Media, 20(4), 336-349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476418796632 [ Links ]

Dardot, P., & Laval, C. (2013). The new way of the world: On neoliberal society. Verso. [ Links ]

Davis, M., & Xiao, J. (2021). De-westernizing platform studies: History and logics of Chinese and U.S. platforms. International Journal of Communication, 15, 103-122. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/13961 [ Links ]

Dubal, V. (2019). An Uber ambivalence: Employee status, worker perspectives, & regulation in the gig economy. Political Science. Publicação eletrónica antecipada. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3488009 [ Links ]

Dyer-Witheford, N., Kjosen, A., & Steinhoff, J. (2019). Inhuman power: Artificial intelligence and the future of capitalism. Pluto Press. [ Links ]

Englert, S., Woodcock, J., & Cant, C. (2020). Digital workerism: Technology, platforms, and the circulation of workers’ struggles’. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 18(1), 132-145. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v18i1.1133 [ Links ]

Fairwork. (2019). The five pillars of Fairwork: Labour standards in the platform economy. https://fair.work/wp-content/uploads/sites/97/2019/10/Fairwork-Y1-Report.pdf [ Links ]

Fairwork. (2020). The gig economy and covid-19: Fairwork report on platform policies. http://fair.work/wp-content/uploads/sites/97/2020/09/COVID-19-Report-September-2020.pdf [ Links ]

Figaro, R. (2018). Comunicação e trabalho: Implicações teórico-metodológicas. Galáxia, (39), 177-189. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-255435905 [ Links ]

Frenken, K., & Schor, J. (2017). Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 3-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.01.003 [ Links ]

Gibbings, S., & Taylor, J. (2019). A desirable future: Uber as image-making in winnipeg. Communication, Culture and Critique, 12(4), 570-589. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz026 [ Links ]

Goux, J. (1973). Économie et symbolique: Freud, Marx. Éditions de Seuil. [ Links ]

Graham, M. (Ed.). (2019). Digital economies at global margins. MIT Press. [ Links ]

Graham, M., & Anwar, M. (2019). The global gig economy: Towards a planetary labour market? First Monday, 24(4). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v24i4.9913 [ Links ]

Grohmann, R. (2018). Signos de classe: Sobre a circulação das classes sociais nos processos comunicacionais. Rumores, 12(24), 293-312. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1982-677X.rum.2018.142047 [ Links ]

Grohmann, R., & Qiu, J. (2020). Contextualizing platform labor. Contracampo, 22(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.22409/contracampo.v39i1.42260 [ Links ]

Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Sage. [ Links ]

Howson, K., Ustek-Spilda, F., Grohmann, R., Salem, N., Carelli, R., Abs, D., Salvagni, J., Graham, M., Balbornoz, M., Chavez, H., Arriagada, A., & Bonhomme, M. (2020). ‘Just because you don’t see your boss, doesn’t mean you don’t have a boss’: Covid-19 and gig worker strikes across Latin America. International Union Rights, 20(3), 20-28. https://doi.org/10.14213/inteuniorigh.27.3.0020 [ Links ]

Huws, U. (2014). Labor in the global digital economy: The cybertariat comes of age. Monthly Review Press. [ Links ]

Huws, U. (2020). Reinventing the welfare state: Digital platforms and public policies. Pluto Press. [ Links ]

iFood. (s.d.). Sobre iFood. https://institucional.ifood.com.br/ifood [ Links ]

Illouz, E. (2007). Cold intimacies: The making of emotional capitalism. Polity Press. [ Links ]

Karatzogianni, A., & Matthews, J. (2020). Platform ideologies: Ideological production in digital intermediation platforms and structural effectivity in the “sharing economy”. Television & New Media, 21(1), 95-114. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476418808029 [ Links ]

Lazar, T., Ribak, R., & Davidson, R. (2020). Mobile social media as platforms in workers’ unionization. Information, Communication & Society, 23(3), 437-453. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1510536 [ Links ]

Leaver, T., Highfield, T., & Abidin, C. (2020). Instagram: Visual social media cultures. Polity. [ Links ]

Liu, W. (2020). Abolish Silicon Valley. Penguin. [ Links ]

Maingueneau, D. (2001). Análise de textos de comunicação. Cortez. [ Links ]

Marazzi, C. (2011). Capital and affects: The politics of the language economy. Semiotext(e). [ Links ]

Morozov, E., & Bria, F. (2018). Rethinking smart cities: Democratizing urban technology. Rosa Luxemberg Stifung. [ Links ]

Mosco, V. (2009). The political economy of communication (2.ª ed.). Sage. [ Links ]

99. (s.d.). Sobre a 99. https://carreiras.99app.com/sobre-a-99/ [ Links ]

Pasquale, F. (2016). Two narratives of platform capitalism. Yale Law and Policy Review, 35(1), 309-319. https://ylpr.yale.edu/two-narratives-platform-capitalism [ Links ]

Plantin, J. C., Lagoze, C., Edwards, P. N., & Sandvig. C. (2018). Infrastructure studies meet platform studies in the age of Google and Facebook. New Media & Society, 20(1), 293-310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816661553 [ Links ]

Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1425 [ Links ]

Popescu, G. H., Petrescu, E., & Sabie, O. (2018). Algorithmic labor in the platform economy: Digital infrastructures, job quality, and workplace surveillance. Economics Management and Financial Markets, 13(3), 74-79. https://doi.org/10.22381/EMFM13320184 [ Links ]

Qiu, J. L., Gregg, M., & Crawford, K. (2014). Circuits of labour: A labour theory of the iPhone era. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 12(2), 564-581. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v12i2.540 [ Links ]

Rosenblat, A. (2018). Uberland: How algorithms are rewriting the rules of work. University of California Press [ Links ]

Rossi-Landi, F. (1973). Il linguaggio come lavoro e come mercato. Bompiani. [ Links ]

Sadowski, J. (2020). The internet of landlords: Digital platforms and new mechanisms of rentier capitalism. Antipode, 52(2), 337-338. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12595 [ Links ]

Scholz, T. (2016). Uberworked and underpaid: How workers are disrupting the digital economy. Polity Press. [ Links ]

Schor, J. B., Attwood-Charles, W., Cansoy, M., Ladegaard, I., & Wengronowitz, R. (2020). Dependence and precarity in the platform economy.Theory and Society, 49, 833-861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-020-09408-y [ Links ]

Schradie, J. (2015). Political ideology, social media, and labor unions: Using the internet to reach the powerful, not mobilize the powerless. International Journal of Communication, 9, 1985-2006. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3384/1413 [ Links ]

Scolere, L., Pruchniewska, U., & Duffy B. E. (2018). Constructing the platform-specific self-brand: The labor of social media promotion. Social Media + Society,4(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118784768 [ Links ]

Silverstone, R. (1999). Why study media? Sage. [ Links ]

Sodré, M. (2019). The science of the commons: Note on communication methodology. Palgrave. [ Links ]

Soriano, C., & Cabañes, J. (2020). Entrepreneurial solidarities: Social media collectives and Filipino digital platform workers. Social Media + Society, 6(2) 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120926484 [ Links ]

Srnicek, N. (2016). Platform capitalism. John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Sun, P. (2019). Your order, their labor: An exploration of algorithms and laboring on food delivery platforms in China. Chinese Journal of Communication, 12(3), 308-323. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2019.1583676 [ Links ]

Uber. (s.d.). Cidadania global. https://www.uber.com/br/pt-br/community/ [ Links ]

Uber. (2020). Carnaval 2020: Uber lança campanha para reforçar respeito. https://www.uber.com/pt-BR/newsroom/carnaval-2020-uber-lanca-campanha-para-reforcar-respeito/ [ Links ]

van Dijck, J, Poell, T., & De Waal, M. (2018). The platform society: Public values in a connective world. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

van Doorn, N. (2017). Platform labor: On the gendered and racialized exploitation of low-income service work in the ‘on-demand’ economy. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 898-914. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1294194 [ Links ]

Voloshinov, V. N. (1973). Marxism and the philosophy of language. Seminar Press. [ Links ]

Wajcman, J. (2019). How Silicon Valley sets time. New Media & Society, 21(6), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818820073 [ Links ]

Williams, R. (2005). Culture and materialism. Verso Books. [ Links ]

Wood, A., Graham, M., Lehdonvirta, V., & Hjorth, I. (2019). Good gig, bad gig: Autonomy and algorithmic control in the global gig economy. Work, Employment & Society, 33(1), 56-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018785616 [ Links ]

Wood, A., Lehdonvirta, V., & Graham, M. (2018). Workers of the internet unite? Online freelancer organisation among remote gig economy workers in six Asian and African countries. New Technology, Work & Employment, 33(2), 95-112. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3211803 [ Links ]

Wood, D. M., & Monahan, T. (2019). Platform surveillance. Surveillance & Society, 17(1/2), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.13237 [ Links ]

Woodcock, J. & Graham, M. (2019). The gig economy: A critical introduction. Polity. [ Links ]

Received: September 19, 2020; Accepted: January 14, 2021

text in

text in