1. Introduction

While tourism is considered one of the most important economic sectors, it is also the most vulnerable and affected by crises that occur in the destination. In recent years, tourism has been hit by a slew of disasters, including natural disasters, economic downturns, terrorism, and pandemics (Ritchie, 2004). The tourism industry is currently coping with the most serious pandemic crisis, known as COVID-19. Saudi Arabia is one of the COVID-19-affected countries. The crisis has had the greatest impact on religious tourism. Saudi Arabia halted air traffic with China as a precautionary measure to cope with the crisis before any COVID-19 cases surfaced in the country (Ali & Alharbi, 2020).

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has gained growing attention both in the professional world and in academic studies because of the socio-economic changes that many businesses have experienced in recent years (Aguinis & Glavas, 2013). In the past, CSR was extensively concerned with international establishments and has now been applied to small and medium-sized partners (Kucukusta et al., 2013). Most businesses recognize that CSR is a high-profile term that is viewed as strategic by the business community (Porter & Kramer, 2006). Internal CSR acts as fundamental Human Resource Management (HRM) operations somehow. In other words, the responsible elements of HRM may be called internal CSR (Nguyen et al., 2020).

However, the procurement of human capital remains a big problem and one of the key business concerns. More recently, growing attention is being paid specifically to internal stakeholders, especially workers, in the field of organisational behaviour and management of human resources (Aguinis & Glavas, 2013). This growth takes CSR and employees to the fore (Low & Ong, 2015).

Enterprises that make more significant investments in employees are more likely to recruit, engage, and retain human capital, thereby enhancing their efficiency (Aguinis & Glavas, 2013). Despite CSR studies spanning several decades and in numerous fields, only a handful of academic studies have explored the relationship between CSR and employees. Employees are an integral part of any company and are strongly impacted by the organisation's CSR initiatives (Low & Ong, 2015). CSR is a complex organisational mechanism in which workers play a key role (Bolton et al., 2011). Evidence obtained over recent decades has indicated that employee investments, such as sponsoring growth and training, can support more productive and efficient business operations and processes. So far, only a few longitudinal studies have been conducted to examine the impact of CSR on employees' attitudes toward work (Turker, 2009; Aguilera et al., 2007). Therefore, the retention of staff is seen as central to retaining company-specific benefits (Brammer et al., 2007). Employee perceptions of CSR and subsequent outcomes are naturally sensitive since they consider their employer to be a second home (Glavas & Godwin, 2013), and hence such perceptions may contribute to the success (Umer & Danish, 2019).

Developing socially responsible practices has become more critical than ever for companies to fulfil the aspirations of their stakeholders (Matten & Moon 2008). Dowling (2001) explained that the views of employees might have a significant effect on how outsiders view an organization. Therefore, the company should begin with an internal CSR program to develop its perceived image of the right employees that can leverage employees' organisational commitment.

The impact of internal CSR on normative organisational commitment in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia's tourism and hospitality hotel business is being investigated in this article. First, the tourism and hospitality industry has been selected as one of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia's most promising service sector industries. Lindgreen et al. (2009) listed previous research that explored the effect of CSR activities on the stakeholders' behaviours toward a firm, although it is still poorly established. We draw faulty assumptions about the effectiveness or effect of internal corporate social responsibility (ICSR) without knowing its impact on the attitude and actions of employees. For businesses, ICSR has become a vital component of social responsibility. Despite this, the internal dimension of CSR has been largely ignored in the research to date (Mory & Göttel, 2015). According to a review of previous literature, most researchers focus their studies on external stakeholders, resulting in less attention being paid to internal stakeholders, particularly employees (Cornelius et al., 2008), and how CSR operations create and maintain a relationship between the organisation and its employees (Fu et al., 2014). Workers are currently receiving more attention because of which ICSR operations have a good impact on employee behaviours and attitudes (Fu et al., 2014).

This study fills a gap in the academic literature by examining the impact of ICSR on normative organisational commitment among business professionals working in the tourism and hospitality industry in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In two ways, the paper contributes to the literature. First, this is the first study on organisational commitment in the tourist and hospitality industry in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to investigate the relationship between normative organisational commitment and employee views of internal CSR. It contributes to our understanding of the determinants of organisational commitment as well as the impact of ICSR on personnel by doing so. The current research has two goals. First, to look at how internal CSR practices have been adopted by the hospitality and tourism industry in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, hail region during the COVID-19 crisis. Second consistent with prior research, look into the impact of internal CSR practices between the hotels and tourism operating in the KSA and its implications for employees’ organisation commitment (Thang & Fassin, 2016). Therefore, the scope of this research is limited to five aspects of internal CSR: health and safety, human rights, training and education, work-life balance, and workplace diversity.

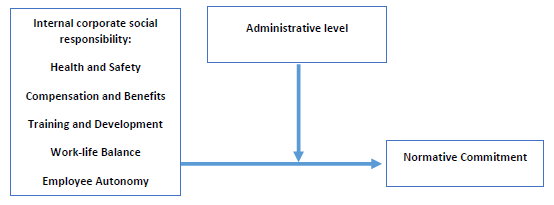

This study has one primary objective: to measure the impact of ICSR activities on employees’ normative commitment. Despite the growing importance of internal corporate social responsibility (CSR) and employee normative organizational commitment (NOC), little is known about the relationships between firms' socially responsible acts and their employees. There has also not been an assessment of the relationship between ICSR practices and NOC in Saudi Arabian Tourism establishments. We focus on the impact of ICSR on NOC, with specific reference to selected tourism and hospitality establishments at Hail, KSA, to close this gap. This research proposes that the administrative level may be a key factor in explaining how internal corporate social responsibility practices influence the normative commitment of employees.

This paper is organised as follows: the study's theoretical framework was provided first. After reviewing the literature about internal corporate social responsibility and normative commitment, the hypotheses were presented. The hypotheses were created based on the findings of previous research. Then, the research model was given. The results of the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the SPSS were presented in accordance with the study model. Finally, the findings were examined in terms of their theoretical and managerial implications, contributions, limits, and future research prospects.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Internal corporate social responsibility

CSR has activities that are internal and external. Internal CSR refers to behaviours that are directly related to employees' physical and psychological well-being (Turker, 2009). Job security, a positive working climate, development of abilities, diversity in the workplace, work-life equilibrium, perceptible engagement of workers, and empowerment are areas of its implementation (European Commission, 2001). On the other hand, external CSR focuses on local communities, corporate partners and providers, clients, public institutions and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and the environment, including charity, volunteerism, and environmental preservation (European Commission, 2001). Relatively neglected was the definition of internal CSR (Aguilera et al., 2007; Aguinis & Glavas, 2013), and less attention was given to internal CSR aspects (Cornelius et al., 2008).

This is illustrated by a review of prior literature reviews, which indicated that most studies focused on exterior components of CSR, leaving internal CSR to receive less attention (Cornelius et al., 2008). As a result, it is not unexpected that the concept of internal CSR is quite imprecise (Thang & Fassin, 2016).

Internal CSR practices include social responsibility practices for workers, particularly in the areas of their protection, health and well-being, business training and engagement, equal opportunity, and the relationship between work and. ICSR relates to how businesses respond to their employee obligations, i.e., the field of work relations (Turker, 2009).

At the personal level, ICSR programs concentrate on workers more specifically and explore their specific needs. They range from activities that promote career growth, such as sponsoring training and professional education, to programs beyond the workplace that satisfy their needs, such as providing pension benefits and profit-sharing (Aguilera et al., 2007). It also entails reducing workplace dangers to their health and safety and creating tasks in ways that encourage involvement and participation (Turker, 2009). It is also becoming more crucial as new generations enter the market with inflated expectations about work-life balance, personal development programs, and career growth chances (Brammer et al., 2007).

When referencing internal CSR, scholars can include numerous definitions, but they share key issues relating to human rights, physical and psychological working conditions, job relationships, and human development (European Commission, 2001; Turker, 2009). This concept can be found in past research that attempted to build several scales to assess internal CSR (2005). This research focuses on four dimensions of internal CSR: job diversity, human rights, training and development, and work-life balance.

The assessment of all internal CSR dimensions and their measurements revealed overlaps between some of the dimensions in the selected studies in earlier research. Work-life balance is an example of overlap utilised in internal CSR research in multiple concepts: employee well-being and satisfaction, job quality, enjoyable work, and work-family relationship (Longo et al., 2005). Previous academic studies, for example, used ten dimensions (Spiller, 2000), while others used nine dimensions (Papasolomou-Doukakis et al., 2005); eight dimensions (Turker, 2009); six dimensions (Castka et al., 2004); four dimensions (Longo et al., 2005) and even two dimensions (Longo et al., 2005; Brammer et al., 2007). Kok et al. (2001) combined internal CSR activities with the following elements: ethical consciousness, working circumstances, minority/diversity, organisational structure and management style, workplace interactions, education and training, and physical climate. Several research studies have found that CSR has strategic value and positively impacts employee organisational bonding (Umer & Danish, 2019). Attracting and retaining human resources may be a competitive advantage for firms (Cavazotte & Chang, 2016). Internal CSR focuses on employees to promote a healthy working environment and expand opportunities (Nguyen et al., 2020).

ICSR standards will boost good employee attitudes and performance more directly by encouraging higher productivity levels through the acquisition and improvement of new skills (Aguilera et al., 2007) and enhancing the organizational efficiency (Mcwilliams et al., 2006).

Individual employee-focused l CSR programs are expected to boost human capital through three mechanisms: (a) more skilled workers are recruited; (b) employee skills are continuously improved; and (c) the workforce is maintained and engaged (Aguinis & Glavas, 2013).

As a result, the organisation's capacity to recruit the best available personnel on the labour market will improve (Kim & Park, 2011). ICSR programs can promote the integrity of the business and promote its positive image (Brammer & Pavelin, 2006).

Investment in ICSR can also enables qualified workers to remain with the enterprise allowing business-relevant expertise to be retained and reducing turnover costs (Cooper & Wagman, 2009; Cavazotte, Chang, 2016). I-CSR thus leads to reduce labour-related costs (Barnett, 2007).

ICSR is seen as an important tool to enhance employee satisfaction, emotional commitment, engagement of workers, and activities to share information (Chaudhary & Akhouri, 2018) and, in turn, improve organizational innovation (Nguyen et al., 2020). Based on the aforementioned debates, this study chose these five variables because these are the basic dimensions that have been employed in earlier studies. Therefore, this study focuses solely on five aspects of internal CSR: health and safety, human rights, training and education, work-life balance, and workplace diversity. Strategic HRM methods, like investments in selective recruiting, employee development, and career security, were connected to decreased turnover and higher employee productivity, according to Huselid (1995) in his seminal survey.

Longo et al., (2005) researched a group of Small and medium enterprises from numerous industrial sectors working in the Emilia Romagna region of Italy. The research aimed to better understand small and medium enterprises' current social commitment while also examining the features of Corporate Social Responsibility. A "grid of value," an instrument capable of assessing stakeholder perceptions of CSR activities in SMEs, was developed. The results show that worker preferences for CSR practices involve workplace health and safety, development of worker proficiency, worker well-being and satisfaction, work adequacy, and social justice. Droms, Hatch, & Stephen (2015) exposed that employees' perceptions of CSR are influenced by their gender. Findings showed that Females had a greater degree of Internalized Moral Identity than men do. Furthermore, females agree more than men that companies should be more useful to the community as a higher level of CSR. Thang and Fassin (2016) used the SET to examine the impact of five internal CSR elements on OC in the service sector: health and safety, human rights, training and education, work-life equilibrium, and place of work diversity. ICSR was found to have a favourable and substantial relationship with OC, according to the findings. Labour relations, health and safety, training, and education all had a significant impact on OC; however, work-life balance and social dialogue did not.

2.1.1 Health and safety

Muchemedzi and Charamba (2006) define Occupational health and safety (OHS) as a scientific method for addressing health issues in a specific workplace or working environment. Because one of the main goals of CSR is to improve connections with stakeholders, socially responsible businesses would strive to reduce the number of workplace injuries (Koo & Ki, 2020). Offering a safe working environment with safety equipment, safety standards, processes, and safety-related events within the organization and demonstrating a commitment to safety by management results in a committed staff (Neal et al., 2000). Any company that fails to invest in its employees' health and safety risks undesirable outcomes such as excessive absenteeism, low productivity, and poor performance (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2021). Although it does not increase the working environment, the deployment of an occupational health and safety system is a very successful strategy for allocating safety money because it stimulates the workforce's behaviours and promotes the development of a health and safety culture (Battani et al., 2009).

2.1.2 Work-life balance

Work-life balance is a broad word that refers to organisational initiatives aimed at improving employees' work and non-work experiences (O'Conell & Russell, 2005). WLB practices are defined as “those that enhance workers' autonomy in the process of coordinating and integrating work and non-work aspects of their lives” (Felstead et al., 2002). Flexible working conditions and features, such as flexible work schedules, job sharing, company-sponsored family gatherings, and paid-time-off rules such as personal days, vacation days, sick days, and so on, can help colleges better manage work-life balance (Heathfield, 2020). Work-life balance is an important aspect of a healthy workplace (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2021).

WLB techniques for employees can help to improve employees' quality of life by reducing work-life conflict, resulting in happier, more motivated, and devoted employees. As a result, the literature emphasises the importance of WLB techniques in helping firms improve productivity, performance, and turnover (Hughes& Bozionelos, 2007). When job and family are incompatible, it has a detrimental physical and psychological impact on individuals, lowering their work performance (Boyar et al., 2005).

2.1.3 Human rights

Human rights are founded on the principles of equality, mutual respect, and dignity, which are shared by all religions and cultures. It ultimately boils down to making real decisions, treating others fairly, and being treated fairly (Canon, 2000). Ethics is concerned with what is right, fair, just, and good, according to Cooper and Schindler (2006). As a result, firms that participate in moral or ethical behaviour produce a source of desire for internal stakeholders, which improves their job performance, commitment, and satisfaction, all of which benefit the organisation. It is expected that their faith in the institution will grow whenever they feel their human rights are protected, cherished, and treated fairly by the institution (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2021).

2.1.4 Training and development:

Training and development are investments made by a company to establish a learning environment that allows employees to improve their knowledge and share their ideas by encouraging the creation of new information and modernisation (Lau & Ngo, 2004). Analytically, in the case of ICSR, training becomes required at each stage of expansion and diversification. To perform better and boost production, employees must gain the necessary knowledge and improve their skills and abilities (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2021).

To maximise job performance, it is critical to equip these unique talents through appropriate training. According to Hogarh (2012), the value of training can only be assessed with a thorough understanding of its direct impact on employee performance. An increase in employee performance leads to an increase in the performance of the organisation. Almost everyone now recognizes the importance of training in a company's success and growth. (Appiah, 2010). According to another study, employee training and education have a considerable impact on employee work commitment and job satisfaction (Foose et al., 2002).

2.1.5 Autonomy

Job autonomy is defined as the degree to which a job provides a significant amount of freedom to the individual in scheduling work and determining how to complete tasks (Marchese & Ryan, 2001). Business autonomy refers to an employee's level of control over how he or she plans and executes his or her work (Morgeson et al., 2005). Because employees believe and consider themselves skilled and innovative in completing their jobs, job autonomy leads to greater job performance (Saragih, 2011; Unguren & Arslan, 2021). The principle is simple when employees believe they have discretionary power in fulfilling their organisational duties, they are more likely to stay with their existing employers due to improved job ownership (Parker & Wall, 1998) and higher willingness to learn new skills (Morgeson & Campion, 2003). More organisational studies have found a significant and positive relationship between job autonomy and organizational commitment (Dude, 2012) than studies that found a weak relationship between the two variables (Gergersen & Black, 1996; Lin & Ping, 2016).

2.1.6 Compensation

Compensation refers to the remuneration that employees receive for their labour. A different pay structure is supplied to each organisation, which is tailored to the vision, mission, and goals (Vizano et al., 2020). Employee compensation is a type of recognition provided to employees for their contribution to the company's success (Silaban& Syah, T2018). Compensation is a strategic human resource function that impacts other human resource activities (Dessler, 2008).

There are many compensation objectives to consider, including 1. Taking pride in one's work; 2. ensuring that justice is served. 3. Keep staff employed. 4. Obtaining high-quality employees 5. Cost-benefit analysis 6. The law on compliance Workers' compensation is a legal obligation that enterprises must meet in a timely, equitable, and work-productive manner. (Vizano et al., 2020). According to Dessler (2008), there are many types of compensation. First, direct monetary payment in the form of a salary, wage incentives, commission, and bonus: second, indirect payment in the form of benefits like insurance and entertainment at the expense of the company: third, non-monetary rewards such as a demanding work environment, flexible working hours, and a prestigious office that are difficult to quantify. Wage or salary, incentives, and allowances are all examples of direct remuneration. Several studies revealed the significant relationship between compensation and organisational commitment (Riana & Wirasedana, 2016; Soon et al., 2008; Nawab & Bhatti, 2011).

2.2 Normative commitment

Organisational commitment has been studied for four decades and continues to spark the interest of researchers and practitioners alike. Initially, the commitment was defined and investigated as a one-dimensional term related to an individual’s emotional attachment to either an organisation or the costs of quitting (Porter et al., 1974). Committed employees are known for being supportive and adhering to the company's goals. They are more loyal to the corporation and feel as if they are a part of it. Employees who are happy with their company's internal social practices are more likely to want to be a part of it. They also exhibit a lower desire to leave work, which helps to reduce employee turnover (Mensah et al., 2017).

In TCM, NC is best known as one of the elements of organisational commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1991; Meyer et al., 2002).

On the other hand, the obligation-based involvement concept has a considerably longer history, reaching back to sociological theory and research in the 1960s and 1970s (Meyer et al., 2010). Normative commitment, which is described as a sense of obligation to support and remain a member of an organisation, is a recent addition to the commitment typology (Allen & Meyer, 1990).

Meyer and Allen's (1997) three-component model (TCM) includes normative commitment as one of three types of commitment, along with emotional and continuation commitment (Meyer et al., 2010). In the 1980s, Wiener and his co-authors conducted a series of studies on what they called a "normative view" of organizational participation (Wiener, 1982; Meyer et al., 2010).

Normative commitment is sometimes rejected as a redundant notion that shares some traits with affective commitment but fails to represent job behaviours adequately. NC has two dimensions that contain both ethical duty and indebted obligations from employees to reciprocate and be loyal to their institution for the advantages received. NC is growing when a “psychological contract” between staff and establishment is founded. Employees who believe they should stay with the company have a high normative commitment (Wasti et al., 2008).

Etzioni (1999) characterised moral involvement as a positive attitude that links employees to the institution with a feeling of duty and has a greater impact on employees' actions than cost-based commitment. Furthermore, workers who follow the lifelong commitment standard agree that remaining in the business is ethical, regardless of how much support or satisfaction the corporation provides its employees during their working years (Meyer et al., 2010).

Normative commitment develops because of a moral obligation to reimburse the organisation for benefits received (e.g., tuition payments or skills training) or socialisation contacts that emphasise the importance of remaining loyal to one's workplace (Scholl, 1981; Wiener, 1982).

This sense of responsibility derived from socialisation interactions may begin with role model observation and/or the conditional application of rewards and punishment (Yucel et al., 2014). According to Meyer & Allen (1991), Normative commitment demonstrates "a believed obligation to remain in the organization."

NC is marked by a feeling of responsibility (e.g., obligation to remain with the organisation or support a change initiative). Despite its technical differences from AC (desire mentality) and CC (cost-avoidance mindset), NC has been proven to have a strong relationship with AC and to share many of the same antecedents and outcomes (Meyer et al., 2002).

Herscovitch and Meyer (2002) characterised NC as “a sense of obligation to assist the transformation” (p. 475). Normative commitment arises when an employee and an institution form a "psychological contract" (Meyer & Allen, 1997). Top management team members regard commitments as a spiritual either necessity or obligated responsibility based on their appraisal of relative individual and company investments (Meyer et al., 2006).

According to Wiener (1982), normative commitment develops because of cultural/familial and organisational socialization processes (Meyer et al., 2010). NC arises when an individual internalises a collection of expectations concerning proper behaviour because of socialisation or when he or she feels compelled to repay the organisation for the benefits obtained (Meyer & Allen, 1991). Individuals might perceive duties as something they should do or something they want to do, according to Berg et al (2001), and obligations perceived as wants were related to more fulfilment and goal achievement than obligations perceived as should. Obligations, like NC, may be experienced differently and so have distinct implications for task satisfaction and performance, according to Bontempo et al. (1990). NC has been measured in many ways over time and has changed. This condition is believed to have contributed to the difficulty in interpreting research findings and general dissatisfaction with the concept.

Among the first measures of a normative-type commitment to an organisation were Marsh and Mannari’s (1977) four-item measure of lifetime commitment and Wiener and Vardi's (1980) three-item measure of normative commitment. Marsh and Mannari's (1977) four-item measure of lifelong commitment and Wiener and Vardi's (1980) three-item measure of normative commitment were among the first assessments of a normative-type commitment to an organisation. Both measures exhibited low reliabilities, and there was little other evidence of their psychometric qualities presented (Meyer & Allen, 1991). Allen and Meyer (1990) created an eight-item NC scale to reflect the internalization of normative influences described by Wiener (1982). Meyer et al. (1993) produced a new six-item measure of NC and a six-item measure of occupational commitment. The changes were considerable, and two considerations spurred them. The first step was to eliminate everything that may be considered NC antecedents. For example, the statement "I was educated to believe in the need of keeping loyal to one organization" arguably illustrates the cultural/family conditioning that Wiener (1982) linked to the emergence of NC. The second issue was quantifying felt responsibility in a broader sense, including duty motivated by a desire to repay the organization for benefits received (Scholl, 1981).

2.3 The relationship between ICSR and NOC

In recent years, research exploring the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and employees' organisational commitment has increased (Glavas & Kelley, 2014). This link is significant because CSR's impact on employee dedication can be translated into increased organisational efficiency (Glavas & Kelley, 2014).

Mory et al. (2015) studied internal CSR and its relationship to employees’ affective and normative organisational commitment empirically). Seven variables are theoretically derived based on social exchange theory for conceptualizing internal CSR. Mory et al. (2015) investigated the correlation between internal CSR and employees' emotional and normative OC. Internal CSR is conceptualised using seven variables derived theoretically from SET. The findings indicate that the related factors that make up internal CSR are present and that the latter has a major impact on employees' AOC while having a slight impact on normative organisational commitment. Affective engagement is often found to play a mediating function NOC. Longo et al. (2005) found that employee priorities for CSR activities include workplace health and safety, the growth of employee skills, worker well-being and satisfaction, job efficiency, and social equity.

Brammer et al. (2007) investigated the association between commitment and worker perceptions of CSR using a model based on SIT. The impact of three aspects of social responsibility on OC was investigated: external CSR (worker perceptions of CSR in society), internal CSR (internal CSR), and external CSR (internal CSR) (procedural justice in the organization and providing worker training). The findings revealed that staff perceptions of CSR significantly affect OC. Moreover, CSR is significant in forming OC as well as job satisfaction and manager goodness. Finally, the ethical treatment of staff was rated as the most important element of an organization's CSR, especially by female staff.

Ali et al. (2010) studied the link between many internal CSR activities and OC based on the SET. The proposed methodology was tested on a group of 336 Jordanian banking frontline staff. According to the findings, all internal CSR dimensions are highly and positively related to affective and normative commitment. However, no internal CSR dimensions have a significant relationship with continual commitment. Thang and Fassin (2016) used the CSR model to investigate the relationship between internal and organizational commitment in the service sector (SET). According to the data, labour relations, health and safety, training and education, and social discourse all had a substantial impact on OC, whereas work-life balance and social conversation had no significant impact.

Through organizational commitment, Ekawati and Prasetyo (2017) evaluated the impact of internal CSR on employee performance in the hospitality industry (in Jakarta, there are 4 and 5 stars hotels). Work-life balance appeared to be a link between OC and employee achievement. According to the findings of this research, managers should concentrate on the factors that have a major impact on OC and determine their impact on employee performance. Only one variable (work-life balance) serves as a moderating factor in the link between OC and employee performance. Based on the studies outlined above, this study posits the following hypotheses.

Hypotheses:

H1: Perceptions of internal corporate responsibility actions contribute to predict positively the organisational normative commitment

- Ha: Perceptions of health and safety measures contribute to predict positively the organisational normative commitment

- Ha: Perceptions of human Rights measures contribute to predict positively the organisational normative commitment

- Hb: Perceptions of training and development measures contribute to predict positively the organisational normative commitment

-Hc: Perceptions of work-Life balance measures contribute to predict positively the organisational normative commitment

-Hd: Perceptions of workplace diversity measures contribute to predict positively the organisational normative commitment

H2: Administrative level moderates significantly the effect of internal corporate responsibility activities on the normative commitment.

3. Methodology

3.1 Research methods

The study used a descriptive and exploratory research design to find out the impact of internal corporate social responsibility measures on employees' normative commitment in T.H. establishments in Hail, KSA. Quantitative analysis was used to analyze the data for this research using SPSS. An exploratory factor analysis was carried out to determine which CSR dimensions were important for the analysis. We also utilized linear regression analyses to find out how independent variables affected dependent variables and how administrative level as a mediator affects the relationship between (health and safety, compensation and benefits, training and development, work-life balance and employee autonomy) and normative commitment.

3.2 Data collection

A pilot test was undertaken before administering the questionnaires to ensure face reliability, validity, consistency, and correctness of the items in the questionnaire. This was done to avoid replies that would have a negative impact on the study's findings. A pilot study was done on 30 employees prior to the data collection process. The elements stayed untouched because the preliminary study concluded that there was no problem. Quantitative data was gathered via a survey using a suitable sampling method. All employees in tourism and hospitality enterprises in the Hail region of Saudi Arabia were included in the study's total population. The staff comprised all administrative levels (executive, middle, and top management) to investigate the mediating role of this variable on the effect of ICSR on NC. The study used structured questionnaires to obtain data from the respondents during the data collecting procedure. The primary data was collected in January and February of 2021. In a conventional method, a sample was chosen. The researchers tracked down people who had been polled in various locations (hotel establishments, travel agencies, restaurants, airlines, car rental agencies). During working hours, the survey was distributed in each firm. Respondents were given questionnaires forms and writing instruments after they agreed. A total of 250 responses were received out of 280 questionnaires sent out, but only 213 were viable, representing an 89.2 per cent response rate.

3.3 Measures

SPSS 26.0 was used to evaluate the acquired data. 250 questionnaires were returned, providing 213 complete and usable packets. The research instrument consists of four parts, of which all contained close-ended questions. The study instrument is broken down into four pieces, each with closed-ended questions. There are seven questions in the first section of the questionnaire related to the demographic characteristics of the respondents in terms of sex, age, social status, nationality, educational level, position, and job experience. The second section of the questionnaire has (21) statements that focus on respondents' perceptions of hospitality and tourist firms' internal corporate social responsibility. The questionnaire's third section has five items that focus on employees' NOC. The researchers employed a four-point Likert scale. 1= Disagree; 2= neutral; 3= agree to some extent; and 4= agree were the four response options. This section explains the research approach used to investigate the predicted model shown in Figure 1. As a result, the current study's model suggests that the ICSR can help predict normative commitment.

There are 21 items for internal corporate social responsibility and 5 items for the normative commitment that were utilized to operationalize the categories. The suggested model is based on past research on commitment measurement (Cavazotte & Chang, 2016; Ehnert et al., 2014; Brammer et al., 2007; Longo et al., 2005; Spiller, 2000; Castka et al., 2004; Kok et al., 2001; Meyer et al., 1993).

3.4 Research Model

The method of explanatory research was used. The goal of explanatory study is to determine the causal relationships between variables. As a result, this research focuses on the administrative level's mediating effect on the impact of internal corporate social responsibility activities on normative organizational commitment. Health and safety, compensation and benefits, training and development, work-life balance, and employee autonomy are all independent factors in the research model, whereas job NC is a dependent variable and administrative level is a mediating variable.

3.5 Analysis

To test research hypotheses in the proposed model (see Figure 1), structural equation modelling using SPSS, version 26.0, was run. Statistical techniques such as descriptive statistics and linear regression analysis were used to achieve the objectives of this study.

4. Results and discussion

4.1 Respondents` profile

The respondents’ profile is presented in Table 2. 250 complete responses were collected from the onsite survey, but 213 questionnaires were only valid for analysis. Furthermore, a majority of respondents were 20 - 30 years old (57.3 %), followed by respondents who were between 31 - 40 (35.4 %) and 36 -45 years old (24.6%). The majority reported a university certificate (55.8%). The majority are single, with more than two-thirds of respondents of Saudi employees. More than half of employees occupy executive positions, followed by positions in middle management. Regarding work experience, less than half of them have less than 4 years, followed by 4-7 years.

4.2 Reliability test

Cronbach Alpha values were used to assess the consistency and internal stability of the variables. It is the most extensively employed in tourism management studies. A usual rule of thumb is that an alpha of 0.60 to 0.70 indicates adequate reliability, and an alpha of 0.8 or higher indicates very good dependability. Reliability and validity are tested for all dimensions (health and safety, compensation and benefits, training and development, work-life balance, employee Autonomy, normative Commitment. Hair et al. (2016) suggested that the value of Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.60; it can be an acceptable lower limit of reliability. According to table 2, the results showed CSR’s Cronbach’s alpha values range from 772 to.889. While organizational commitment, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.661. The Cronbach’s alpha value for the total scale is 925.

3.3 Descriptive statistics

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics. The health and safety mean value is 3.66, the mean value of compensation and benefits is 3.36035, and training and development is. The mean value of work-life balance is 3.422525. Further, the mean value of employee autonomy is 3.44978. It is also important to mention that Normative Commitment is 3.12302.

Table 3 Mean and standard deviation of the study variables

| Variables | N | Mean | STD. Deviation |

| Health and safety | |||

| My establishment provides safe and healthy work conditions in the work environment during COVID-19. | 213 | 3.8263 | .46870 |

| My establishment provides a periodic medical examination for employees during COVID-19. | 213 | 3.4742 | .82733 |

| My establishment controls employees' commitment to health and safety rules during COVID-19. | 213 | 3.6948 | .63381 |

| My establishment provides medical insurance to infected employees with COVID-19. | 213 | 3.6808 | .74064 |

| Total mean | 3.669025 | 0.66762 | |

| Compensation and benefits | |||

| My establishment provides financial supports for coping with COVID-19. | 213 | 3.4742 | .89313 |

| My establishment provides employees with financial assistances to fulfil their life needs during COVID-19. | 213 | 3.3146 | .91612 |

| My establishment did not decrease the pay rate during COVID-19. | 213 | 3.4272 | .84709 |

| Despite COVID-19 crisis, my establishment provides annual increments to employees. | 213 | 3.2254 | .96930 |

| Total mean | 3.36035 | 0.90641 | |

| Training and development | |||

| My establishment provides financial support for training in coping with COVID-19. | 213 | 3.3709 | .95586 |

| My establishment organizes health and safety programs training employees to face COVID-19. | 213 | 3.4085 | .95033 |

| My establishment updates the training programs according to COVID-19 developments. | 213 | 3.3239 | 1.00623 |

| My establishment provides career consultants and experts in dealing with epidemic crises to assist the employees. | 213 | 3.2019 | 1.01943 |

| Total mean | 3.3263 | 0.9829625 | |

| Work-life balance | |||

| My establishment allows employees to choose part-time work during COVID-19. | 213 | 3.4178 | .88970 |

| My establishment will allow me to schedule my desired days off during COVID-19. | 213 | 3.4601 | .86032 |

| My establishment takes initiatives to manage the work-life of its employees during COVID-19. | 213 | 3.3615 | .86101 |

| My establishment allows no conflict between the employees' own life and work during COVID-19. | 213 | 3.4507 | .88150 |

| Total mean | 3.422525 | 0.8731325 | |

| Employee autonomy | |||

| My establishment allows employees' participation in making decisions related to COVID-19 regardless of positions. | 213 | 3.5728 | .77131 |

| My establishment is effectively utilizing the employees' suggestions in coping with COVID-19. | 213 | 3.5399 | .85482 |

| My establishment allows employees to make some decisions regarding COVID-19 without report to the top level. | 213 | 3.0892 | 1.06245 |

| My establishment provides necessary facilities to correct the errors in coping with COVID-19. | 213 | 3.4789 | .84996 |

| My establishment provides communication channels between employees and managers to exchange information about COVID-19. | 213 | 3.5681 | .79581 |

| Total mean | 3.44978 | 0.86687 | |

| Normative commitment | |||

| I do not believe that the employee must always be loyal to his/her establishment, especially in times of crisis such as COVID-19. | 213 | 3.3052 | 1.10566 |

| Jumping from one establishment to another does not seem unethical to me, especially in times of crisis such as COVID-19. | 213 | 2.8592 | 1.23963 |

| Because I feel that loyalty to my establishment is crucial, especially in times of crisis like COVID-19, I must maintain my moral commitment. | 213 | 3.3239 | 1.02019 |

| If I got a better offer for a job elsewhere, I would not leave my establishment, especially in a crisis such as COVID-19. | 213 | 2.9014 | 1.30480 |

| I would not leave my establishment because I have a sense of obligation to it, especially in times of crisis such as COVID-19. | 213 | 3.2254 | 1.11842 |

| Total mean | 3.12302 | 1.15774 | |

3.4 Exploratory factor analysis of the constructs of ICSR and NOC

Exploratory factor analysis is a multivariate statistical approach that is commonly used to reduce and summarize data. Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson (2010) used exploratory factor analysis to condense the information contained in the original variables into a smaller set of variates (factors) with the least amount of information loss to arrive at a more prudent conceptual understanding of the set of measured variables. To assess the type of extraction, both principal component analysis and factor analysis were utilized. EFA aids in determining the structure of the link between variables and respondents' perceptions. The EFA approach was used as a measurement instrument in this study to discover various dimensions of quantifying the influence of ICSR on NOC. After a thorough assessment of the literature, twenty-six items were chosen for this purpose. On a 4-point Likert Scale ranging from 1- disagree to 4- agree, 213 respondents provided information for further analysis of the sample.

3.5 Sample adequacy

To make an exploratory factor analysis of the pre-survey data, SPSS 26.0 was used to obtain the KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) value and the Bartlett Test of Sphericity results. As indicated by Comrey, pre-analysis testing for the appropriateness of the complete sample for factor analysis was performed (1978). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test was used to determine sample adequacy (Field, 2005; Kaiser & Rice, 1974). A result of (.900) showed that the sample was suitable for factor analysis.

Additionally, in the present study, Bartlett’s test is used to test whether the correlation between all the variables is zero. The test value (2735.438), the salience value of the Bartlett test of Sphericity was .000, which was quite significant. These results showed that the pre-survey sample was suitable for factor analysis. As a result, exploratory factor analysis might be employed for future research.

Table 4 KMO and Bartlett's Test

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | .900 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 2735.438 |

| df | 300 | |

| Sig. | .000 | |

Although well-established tools were employed to measure the constructs, the dimensionalities of all variables were examined using exploratory factor analysis (EFA). After that, the items with low communality figures (0.4) are deleted, and the common component is grouped in the same dimension. Only one variable (AUT3=.393) was removed from the EFA analysis in this study.

3.6 Loading factors

The contribution range of the items defined by the scale and the related dimensions was between.417 and.786, meeting the questionnaire's specified critical level, according to the data in Table no.5. After entering variables into SPSS, EFA revealed that all 26 items sufficiently represent their respective constructs, except for one item, AUT3 =.393. The factor loadings of each variable onto each factor are listed in Table 5. SPSS by default displays all loadings; however, a request was made to suppress all loadings less than 0.4 in the report.

Table 5 Communalities

| Initial | Extraction | |

| SH1 | 1.000 | .742 |

| Sh2 | 1.000 | .765 |

| Sh3 | 1.000 | .671 |

| Sh4 | 1.000 | .415 |

| Com1 | 1.000 | .587 |

| Com2 | 1.000 | .643 |

| Com3 | 1.000 | .417 |

| Com4 | 1.000 | .627 |

| Tr1 | 1.000 | .754 |

| Tr2 | 1.000 | .687 |

| Tr3 | 1.000 | .645 |

| Tr4 | 1.000 | .792 |

| WLB1 | 1.000 | .761 |

| WLB2 | 1.000 | .716 |

| WLB3 | 1.000 | .651 |

| WLB4 | 1.000 | .623 |

| AUT1 | 1.000 | .479 |

| AUT2 | 1.000 | .649 |

| AUT4 | 1.000 | .545 |

| AUT5 | 1.000 | .553 |

| NC1 | 1.000 | .786 |

| NC2 | 1.000 | .691 |

| NC3 | 1.000 | .681 |

| NC4 | 1.000 | .755 |

| NC5 | 1.000 | .697 |

Note: Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis.

3.7 Factor extraction

To support the strength of the components, factor analysis was performed with 1 as the Eigenvalue. When the rotation converged in its iterations, five factors were retrieved. The total number of factors in the study was determined by using Eigenvalues greater than one. On this ground, five factors (components) have been identified with Initial Eigen Values above 1. The second column of the table identifies the percentage of variance, and the third column provides information about the cumulative percentage of variance. Since only five components have been allocated as factors, a cumulative percentage of the five components gives an idea about the total coverage of the study. In this study, the cumulative percentage of five components is 67.749, of the area of study, which is quite good. From table 6, it is also observed that the first component itself covers 43.978% of the variance, which is also very appropriate for the study.

Table 6 Total Variance Explained

| Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadingsa | |||||

| Component | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total |

| 1 | 8.796 | 43.978 | 43.978 | 8.796 | 43.978 | 43.978 | 6.756 |

| 2 | 1.631 | 8.155 | 52.133 | 1.631 | 8.155 | 52.133 | 6.684 |

| 3 | 1.164 | 5.822 | 57.955 | 1.164 | 5.822 | 57.955 | 5.785 |

| 4 | 1.047 | 5.233 | 63.188 | 1.047 | 5.233 | 63.188 | 5.566 |

| 5 | .912 | 4.561 | 67.749 | .912 | 4.561 | 67.749 | 2.629 |

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. / a. When components are correlated, sums of squared loadings cannot be added to obtain a total variance.

3.8 Rotated component matrix

The factor model is then rotated to convert the factors and make them more understandable. The rotation phase transforms a factor matrix in which most factors are associated with many variables into one in which each factor has zero loadings for only a few variables. For rotating a matrix, there are numerous options. The approach utilized in this research is Orthogonal (Varimax) rotation, a widely used method for reducing the number of variables with large loadings on a factor. This should improve the factors' interpretability. Table no.7 shows the rotated factor matrix using Varimax rotation, with each factor identifying itself with a few sets of variables.

The variables that identify with each of the elements were sorted. Table no.7 shows the factor loadings after rotation. The items that cluster on the same factor suggest that factor 1 represents training & development, compensation, and benefits, factor 2 represents work-life balance, factor 3 represents health, and safety, factor 4 represents employee autonomy, and factor 5 represents a normative commitment. Items, which are less than five, were deleted. SO, Sh4 in factor 3 and Aut1 in factor 4 were suppressed in the output.

Table 7 Rotated matrix

| Component | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Tr1 | .947 | ||||

| Tr4 | .876 | ||||

| Tr2 | .852 | ||||

| Tr3 | .763 | ||||

| Com2 | .675 | ||||

| Com4 | .606 | ||||

| Com1 | .581 | ||||

| Com3 | .564 | ||||

| WLB1 | .922 | ||||

| WLB2 | .880 | ||||

| WLB4 | .786 | ||||

| WLB3 | .613 | ||||

| SH1 | .970 | ||||

| Sh3 | .793 | ||||

| Sh2 | .744 | ||||

| AUT2 | .806 | ||||

| AUT4 | .694 | ||||

| NC1 | .851 | ||||

| NC4 | .844 | ||||

| NC3 | .768 | ||||

| NC2 | .765 | ||||

| NC5 | .668 | ||||

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. a. Rotation converged in 6 iterations.

1.Hypotheses Test

H1: Perceptions of internal corporate responsibility actions contribute to predict positively the organizational normative. Commitment

To find the relationship between the internal CSR and NOC, a simple linear regression model was used. Internal social responsibility was considered an explanatory variable and normative commitment as a dependent variable. The regression model's findings revealed that the ICSR and NC variables had a significant correlation. The F value and its accompanying P-value (F=91.203, P=.000b) indicate this.

The ICSR explains 30% of variations in NC showing the strength of the relationship between ICSR and NC its P-value, it may be decided that the model is valid and there is a positive correlation between ICSR and NC. There was a significant correlation between Factor 1 (training & development and compensation and benefits) and NC variables. This can be inferred from the F value and its associated P-value (F=56.411, P=.000b).

Factor 1 explains 21% of variations in NC, showing the positive relationship between the two variables. There was a significant relationship between factor 2(work-life balance) and NC variables. This can be inferred from the F value and its associated P-value (F=69.427, P=.000b). The work-life balance explains 24 % of variations in NC showing a positive relationship between the work-life balance and NC. There was a significant relationship between Factor 3 (health and safety) and NC variables. This can be inferred from the F value and its associated P-value (F=51.339, P=.000b). The health and safety item explains 19% of variations in NC showing a positive relationship between health and safety and NC. There was a significant relationship between Factor 4 (employee autonomy) and NC variables. This can be inferred from the F value and its associated P-value (F=51.530, P=.000b). The employee autonomy explains 20% of variations in NC showing the positive relationship between the two variables.

Table 8 The impact of internal corporate responsibility activities on the organisational normative commitment

| Dependent variable | Predictors | R | R Square | F value | F signifiance | Beta | T value | T signifiance |

| F5 (Normative commitment) | Internal CSR in general | .549a | .302 | 91.203 | .000b | .175 | 9.550 | .000 |

| F 1 | .459a | .211 | 56.411 | .000b | .299 | 7.511 | .000 | |

| F2 | .498a | .248 | 69.427 | .000b | .571 | 8.332 | .000 | |

| F 3 | .442a | .196 | 51.339 | .000b | 1.026 | 7.165 | .000 | |

| F 4 | .443a | .192 | 51.530 | .000b | 1.159 | 7.178 | .000 |

H2: Position moderates significantly the effect of internal corporate responsibility activities on the normative commitment.

A moderator variable can change the direction of a predictor variable's connection with a dependent variable (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). According to this study, the effect of internal CSR on normative commitment is conditional on (or strongly regulated by) the administrative level. We used linear regressions to analyze the data. Table 9 displays the results. These findings suggest that the connection between ICSR and the administrative level, in general, impacts normative commitment.

To find the moderating role of the position on the effect of ICSR on the NC, a linear regression model was used in which ICSR*administrative were considered as explanatory variables and Normative commitment as dependent variables. The results confirmed that position moderates the relationship between ICSR and the NC. This can be inferred from the F value and its associated P-value (F=11.466, P=.001b). The results are shown in Table 9.

It was also found that interaction between administrative levels which each set of ICSR affects the normative commitment. The interaction term between position and factor1 explained a variance in predicting normative commitment (F= 12.901, p= .000b).

The interaction term between position and factor 2 explains a variance in predicting normative commitment (F=10.685, p =.001b). The interaction term between administrative level and factor3 explains variance in predicting normative commitment (F=5.550, p =.019b). The interaction term between administrative level and factor 4 explains variance in predicting normative commitment (F=12.672, p =.002b).

Table 9 the moderating role of the effect of internal corporate responsibility actions on the normative commitment

| Dependent variable | Predictors | R | R Square | F value | F significance | Beta | T value | T significance |

| ICSRLEVEL | .227a | .052 | 11.466 | .001b | .016 | 3.386 | .001 | |

| Normative commitment | inter1 | .240a | .058 | 12.901 | .000b | .240 | 3.592 | .000 |

| Normative commitment | inter2 | .220a | .048 | 10.685 | .001b | .061 | 3.269 | .001 |

| Normative commitment | inter3 | .160a | .026 | 5.550 | .019b | .072 | 2.356 | .019 |

| Normative commitment | Inter4 | .238a | .057 | 12.672 | .002b | .167 | 3.560 | .002 |

5. Discussion of results

Previous research has tended to focus on exterior components of CSR, resulting in less attention to internal CSR. In our study, to fill the knowledge gaps, we paid attention to CSR’s internal mechanisms from the perspective of tourism and hospitality establishments' employees. This research aimed to investigate the impact of internal CSR on NOC and explore how the administrative level moderates the relationship between internal CSR and NOC.

This study's findings are intriguing, and they contribute to the empirical data of tourism and hospitality establishments in Saudi Arabia, particularly in Hail. Our findings indicate that ICSR is linked to NC. More specifically, when employees believe that the company cares about them by providing health and safety, compensation and benefits, training and development, work-life equilibrium, and member of staff autonomy, they are more likely to work enthusiastically and express a higher level of NOC to the company.

The probable reason for this significant relationship between internal CSR and NOC could be attributed to the staff`s perception that actions of health and safety, compensation and benefits, training and development, work-life equilibrium, and employee autonomy are better than in other establishments. Thus, these employees might feel to be obligated to remain with their tourism and hospitality establishments. In this context, these types of internal corporate social responsibility practiced by the concerned establishments have to be supported by the top management to keep their experienced and talented staff.

We can see that these activities are seen as one of the most important instruments for combating staff turnover and gaining a competitive advantage. Our findings are similar to those of prior research (Turker, 2009; Mory & Göttel, 2015; Ekawati & Prasetyo, 2017; Nguyen et al., 2020; Edgar & Geare, 2005).

In fact, according to Vuontisjärvi (2006), the most common employee-focused policies and practices in these companies are training and staff development, compensation and benefits, engagement and staff participation, values and principles, employee health and well-being, measurement of policies, work policy, employment protection, equal opportunity (diversity), and work-list.

According to a study, three factors of CSR have a beneficial impact on employees' OC expectations in the CSR to community dimension (Maung and Chotiyaputta, 2018). Furthermore, while work duration was relevant, there was no evidence that workers' CSR perceptions and commitment levels were influenced by their job title, education, or income level. According to this study, the effect of internal corporate social responsibility on normative commitment is dependent on (or severely restricted by) the administrative level.

This research has implications and relevance for management theory and practice. The findings of this study contribute to the fast-growing CSR and human resource management literature because it is the first study in the field of tourism and hospitality in Saudi Arabia to investigate the relationship between internal CSR and NC. We discovered that internal CSR has a positive and significant effect on normative commitment when we calculated the impact of internal CSR on that dimension. The implications and relevance of this study for management theory and practice are significant. Because it is the first study in the field of tourism and hospitality in Saudi Arabia to analyze the relationship between internal CSR and NC, the findings of this study contribute to the rapidly developing CSR and HRM literature.

Internal CSR may result in employee commitment as a result. Hail City's tourism and hospitality businesses must endeavour to enhance internal working conditions to develop sustainably. The outcomes of this study will aid in the promotion of internal CSR initiatives and the encouragement of socially responsible activities for internal tourist market players. This empirical result has also confirmed the SET.

In addition, our research discovered that the administrative level moderates the positive relationship between internal corporate social responsibility measures (health and safety, compensation and benefits, training and development, and employee autonomy), as its interactions with the previous sets are positively correlated with normative commitment. It was not quite as strong.

6. Conclusions

This study increases our understanding of the effect of the ICSR on employees’ NOC. The factor Analysis retains all employee normative organizational commitment components and ICSR, indicating that the two variables are significantly connected. Furthermore, the factors created by the two notions are highly connected. The findings of this study support the assertion that CSR has a significant impact on an employee's normative commitment to his or her company. The linear regression analysis shows that ICSR and NOC have a favourable connection.

ICSR is favourably associated with normative commitment, according to our findings. Furthermore, the findings reveal that the administrative level moderates the link between the two variables in general, explaining variance in normative commitment prediction. This study aims to add to the scholarly debate on employee CSR and its impact on NOC. This research also examines and supports the value of CSR for workers.

6.1 Implications

The findings of this study present several involvement opportunities for the tourism and hospitality establishments and planning and policymakers of the tourism industry in Saudi Arabia. Tourism and hospitality businesses in Saudi Arabia, in particular, should integrate CSR strategies into their human resource policies, realizing that expressing concern for employees' well-being goes a long way toward enhancing employee loyalty, efficiency, and, eventually, the company's growth. Managers must enhance and maximize their engagement in CSR for employees to promote organisational normative involvement. Top executives can use this study as a reference to assess the most anticipated characteristics of ICSR and strategically integrate it into the organization's structure to motivate people to engage. As a result, in order to deliver an extraordinary and memorable working life, management must address key ICSR characteristics such as work-life balance and training and development. By including these elements, both parties will become aware of the mutual benefits, and, as a result, the relationship will improve. According to Santoso (2014), companies may be required to offer workers adequate working conditions, a fair organizational structure, and a family-friendly work environment.

6.2 Limitations

This study has several limitations. Furthermore, we can also find future research based on these limitations. Firstly, the sample size applied was relatively small. Because the sample size was less than 500, the results obtained did not represent the best potential outcome. As a result, future researchers should think about employing a bigger sample size. However, the current study is limited to the hospitality and tourism industry in the KSA. Therefore, results cannot be generalised to other countries since the business environment is also different in other countries.

6.3 Future Research

Only the impact of internal corporate social responsibility on normative commitment is examined in this study. First, we will look into the moderating effect of nationality on the relationship between ICSR and organizational commitment in future research.

Second, we will test how ICSR affects other aspects of organizational commitment (affective and continuance commitment). The current study was limited to quantitative research approaches; qualitative research involving interviews with managers and owners in the hospitality and tourism industries could improve the findings.

Acknowledgement

This research (RG-20135 ) was supported by the deanship of scientific research, Hail, University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Therefore I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to all staff of the deanship of scientific research for their great efforts and for their continuous assistance.