1. Introduction

Globally, internet use is growing by more than 7% annually, resulting in over 875,000 new users per day, who are online for an average of 7 hours every day. Unsurprisingly, given that 5.20 billion people use mobile phones worldwide (Datareportal, 2020), almost 90% of these users use smart devices to surf the net. While two-thirds of the world has a mobile phone, of whom almost three-quarters use smartphones (3.5 billion users) (O’Dea, 2020). Hundreds of millions of users have switched to smartphones since 2020. According to current data, smartphone usage is increasing by 8% annually, with more than 1 million new smartphones being used every day (Datareportal, 2020). More than half of the world’s population, 4.14 billion people, uses at least one social media platform. In the last 12 months, 520 million new users joined social media between July 2020 and July 2021. There are 4.48 billion social media users in the world today. Social media users are growing by 13% annually. (Datareportal, 2021). Given the future development of new technologies, digital tools are predicted to increase even more.

Internet use has both positive and negative effects on human life (Keles et al., 2020; Sum et al., 2008) since technological tools are always connected to mobilization and the internet. For instance, phone use may become problematic if individuals constantly check their phones for no reason (Park, 2005). This behavior is considered a sign of a new psychological disorder of nomophobia, standing for NO MObile Phone, defined as a fear of being deprived of one’s smartphone and mobile internet (Bhattacharya et al., 2019). Overuse of ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies) have been associated with techno-stress, anxiety, low self-esteem, and depression (Bhattacharya et al., 2019; Elhai et al., 2016; Farooqui et al., 2018; Hayes et al., 2016; Hoge et al., 2017; Scott et al., 2017), addiction (Hoving, 2017; Paris et al., 2015; Pearce & Gretzel, 2012), overweight (Vandelanotte et al., 2009), digital eye strain (American Optometric Association, 2020), sleeping disorders (Kwon et al., 2013; Soni et al., 2017), and loneliness (Kwon et al., 2013; Odac & Kalkan, 2010).

If people experience these problems while on holiday, they will not rest, mentally or spiritually. To reduce or eliminate these ICT- related problems, the concept of digital detox has emerged. Digital detox is based on the idea of balance, similar to mindfulness, and is seen as a tool for taking short breaks to relieve stress and learn about self-regulation (Glomb et al., 2011).

Drawing on shorter experiences, such as disconnected restaurants and cafes, digital detox has been applied to longer- term tourism products called digital detox holidays (Cai et al., 2020) and digital detox camps (Karlsen, 2020). Digital detox has recently become a widely used term in tourism both in practical (Pawłowska-Legwand & Matoga, 2020; Pekyaman et al., 2015) and academic contexts (Amato et al., 2019; Egger et al., 2020; Emek, 2014; Hoving, 2017). For example, travel agencies are now offering digital detox holidays to enable customers to disconnect from their digital devices and participate in detoxification treatments. These products attract tourists wanting to stay away from technology to experience a healthier lifestyle, physically, mentally, or spiritually.

There is confusion in the literature since many different terms are used to refer to this concept apart from digital detox holidays, such as digital-free tourism, unplugged tourism, and disconnected tourism. The present study tries to clarify this confusion by focusing on the digital detox holiday as a tourism form. To do so, the study first proposes a model of the digital detox experience in tourism, based on a review of previous research. Second, bibliometric analysis is used to review publications focusing on the growing trend of digital detox holidays, based on primary and secondary sources in Google and Scopus databases.

2. Literature review

2.1 The concept of digital detox

Etymologically, the word ‘detox’ refers to a process to minimize the levels of hazardous substances. However, unlike abstinence, which is recommended to overcome substance abuse, digital detox is a short-term “cleansing” (Syvertsen & Enli, 2020). Although it is more than ten years old, digital detox was first included in the Oxford Dictionary in 2013 (Syvertsen & Enli, 2020), which defines it as “A period during which a person refrains from using electronic devices such as smartphones or computers, regarded as an opportunity to reduce stress or focus on social interaction in the physical world” (Oxford Dictionary, 2013). Similarly, the Technology Dictionary describes it as a situation when an individual stops or suspends using digital tools for social interactions and activities. This allows the individual to relieve the stress and anxiety caused by overuse of ICTs. More simply, digital detox refers to the time when a person avoids using any digital tools (Techopedia, n.d.a.). One common assumption of all these definitions is that the current use of ICT can be dangerous and unhealthy. Hence, the term appears in a long series of metaphors about health used by media critics (Syvertsen, 2017). According to both Oxford (2013) and the Technology Dictionary (Techopedia, n.d.a), a digital detox is primarily an opportunity to improve mental well-being by taking some time to reduce one’s dependence or obsession with ICTs and to enjoy the real world. Digital detox is realized by shutting down all mobile phones, smartphones, tablets, computers, etc. - in other words, all ICTs (Pathak, 2016). While digital detox means avoiding the use of online media and games, it also includes avoiding other media, such as televisions or business-related digital tools and programs.

Digital detox takes advantage of the promise of authenticity by offering ways to counter virtual experiences in conjunction with online interactions, faceless communication, and artificial intelligence (Syvertsen and Enli, 2020). This authenticity is based on individual responsibility (Madsen, 2015; Pathak, 2016). The argument for digital detox is expressed as resistance to the negative effects of ICTs. Digital detox describes efforts to take a longer or shorter break from online or digital media, as well as other efforts to restrict the use of smartphones and digital tools (Syvertsen & Enli, 2020). Digital detox breaks can range from spending an hour or two without a mobile phone detox holidays lasting several weeks (Zahariades, 2017). Digital detox, which has become a fashionable term, is frequently used in media channels. Temporary breaks in technology use are seen as a tool to awareness and learn self-regulation to reduce stress(Glomb et al., 2011). The awareness and balance approach focuses on controlling ICT use and raising awareness of the balance of time spent in the digital and physical environments. This ensures a healthy balance between normal life and time spent using digital tools. The need for digital detox can be directly proportional to rate of ICT usage since overuse can cause various health problems that lead people to need digital detox.

2.2 Digital detox holiday: as a new form of disconnected or unplugged tourism

Digital detox is a growing phenomenon that offers a response to information overload and the aforementioned effects that come with new media and digital devices. Tourism research on this topic suggests that focusing on the real world rather than the digital world helps overcome the negative impacts of ICTs on the travel experience (Bhattacharya et al., 2019; Egger et al., 2020; Hoving, 2017). Various studies define digital detox holidays as a form of unplugged tourism (Pawłowska-Legwand & Matoga, 2020, p. 17), a term which various travel agencies now use in their product listings (e.g., www.wellbeingescapes.com and www.bookyogaretreats.com). Travel websites often use digital detox holidays alongside terms like yoga, digital detox retreat, well-being, and tech-free tourism as they have a similar philosophy (e.g., www.tajhotels.com). Organizations now offer off-line events, such as nature-based holiday packages or boot camps in areas where people can avoid ICTs and the internet. These organizations target customers wishing to relax by escaping from digital living (Kuntsman & Miyake, 2016, p.10). Constant internet connectivity due to increasing ICT usage makes people tense, which then causes them to try to escape (Glomb et al., 2011). Given these developments, tourism research has focused on digital detox holidays in the last decade (Syvertsen & Enli, 2020), described in various ways, such as digital-free tourism (Egger et al., 2020a; Li et al., 2018), digital free travel (Cai et al., 2020), digital-free holidays (McKenna et al., 2020), unplugged tourism (Paris et al., 2015; Pawłowska-Legwand & Matoga, 2020), disconnected tourism (Dickinson et al., 2016), and deadzone in tourism (Pearce & Gretzel, 2012).

Pearce and Gretzel (2012) were among the first to research dead zones in disconnected tourism. They found that technology is likely to be used for non-holiday purposes if it is available during a holiday. They suggested that tourists could benefit from “technology dead zones”, which they defined as “places with limited or no internet technology access” (Pearce & Gretzel, 2012, p. 39). Similarly, Li et al. (2018) proposed “digital-free tourism (DFT)”, defined as “tourism spaces where internet and mobile signals are either absent or digital technology usage is controlled”. The increasing popularity of tourism and accommodation products like DFT, digital-free cafes and restaurants, digital dead zones, disconnected holidays, and digital detox camps has led to increased academic interest (Cai et al., 2020; Egger et al., 2020).

Important articles on disconnected tourism, particularly digital detox, include Cai et al. (2020), Li et al. (2018), Paris et al. (2015), Pawłowska-Legwand and Matoga (2020), and Pearce and Gretzel (2012). Li et al. (2018) described three stages of media discourse regarding digital-free tourism, which is very close to digital detox holidays: introduction (2009-2013), growth (2014-2015), and development (2016-2017). They defined that last stage as “taking a break from technology” and “the essence of life”. They defined DFT as “nature-based, remote, rural and consciously designed: retreat, wellness and mindfulness” and digital detox as “a period during which a person refrains from using electronic devices such as smartphones or computers, regarded as an opportunity to reduce stress or focus on social interaction in the physical world”. Neuhofer and Ladkin (2017) defined it as “switching-off for a specific period” while Fan et al. (2019) described the digital detox traveler as “a person who uses the internet to a limited extent to connect with their home while traveling”.

Based on these, digital detox holidays can be defined as follows: a tourism form in which individuals who want to get away from ICTs due to social, physical, or mental effects are voluntarily and consciously engaged in activities such as outdoor, experiential, well-being, and health activities in places (e.g., digital detox hotels, campsites, rural areas, small towns, or woodlands) that have none limited connectivity, and remain unconnected during their holiday except for calling home.

Hospitality businesses, food and beverage businesses, and even some belief groups have organized important digital detox campaigns. For example, since mid-2012, Eva Restaurant in Los Angeles has offered discounts to guests who hand over their smart devices to staff (Emek, 2014). Having begun as a movement, digital detox initiatives later turned into digital detox holidays. These first emerged on Saint Vincent and Grenadine in the Caribbean (Pekyaman et al., 2015, p. 574) before spreading to the USA in 2013 and Europe in 2015. Hospitality businesses offering digital detox are often surrounded by nature and historical sites. Historical and isolated buildings (e.g., monasteries) or camping sites are the preferred accommodation types for digital detox holidays to break from daily routines and reduce stress levels thanks to their green environment (Amato et al., 2019). Although most hospitality facilities offer advanced ICT, digital detox hospitality facilities are also increasing. The Four Seasons hotel group, for example, has not followed the trend towards technology intensity in tourism. Since 2018, it has offered digital detox to guests at its Seychelles hotel on Desroches Island, which lacks a mobile phone base station. Instead, wireless internet service is only available within the facility. To encourage its customers to avoid intense technology use for a few weeks, the hotel allocates a bicycle for each guest and organizes yoga, canoeing, snorkeling, and diving activities (Gençoğlu, 2019).

Digital detox holidays are associated with health tourism, chosen by people who seek physically, mentally, or spiritually healthy lifestyle experiences (Emek, 2014; Amato et al., 2019). Such holidays can also be integrated with nature tourism, youth tourism, sports tourism, highland tourism, thermal tourism, rural tourism, farm tourism, and adventure tourism (Pawłowska- Legwand & Matoga, 2020; Sunar et al., 2018). Digital detox- related tourism development has been seen in remote areas, coastal regions, islands, high mountains, wild areas, hot springs, and undiscovered places. For example, Swiss Tourism promotes private detox wellness packages and relaxation sports classes in mountain hotels with rooms lacking TV and Wi-Fi access. Hotels are deliberately located in areas with poor mobile phone reception (Pawłowska-Legwand & Matoga, 2020, p. 8). Travel agencies have created three types of digital detox holiday packages to disconnect from digital devices and participate in detoxification treatments (Hoving, 2017, p. 4):

Detox packages that make the tourist responsible for not bringing digital devices to the destination;

Digital detox packages for businesses and destinations that do not offer digital devices but provide ICT connectivity;

Packages for destinations that are either far from ICT connections or lack connection.

Despite the benefits, the inability to connect can lead to severe anxiety in tourists (Germann Molz & Paris, 2013), while those with high levels of technology addiction cannot be satisfied by a “disconnected” environment (Porter and Kakabadse, 2006). Thus, digital detox holidays must be chosen voluntarily by those willing to move away from technology. Such breaks reduce their stress by increasing their self-awareness. They also increase resilience at work and in daily life, and enables them to focus on their surroundings and relationships (Smith & Puczkó, 2015).

2.3 A model of the digital detox experience in tourism

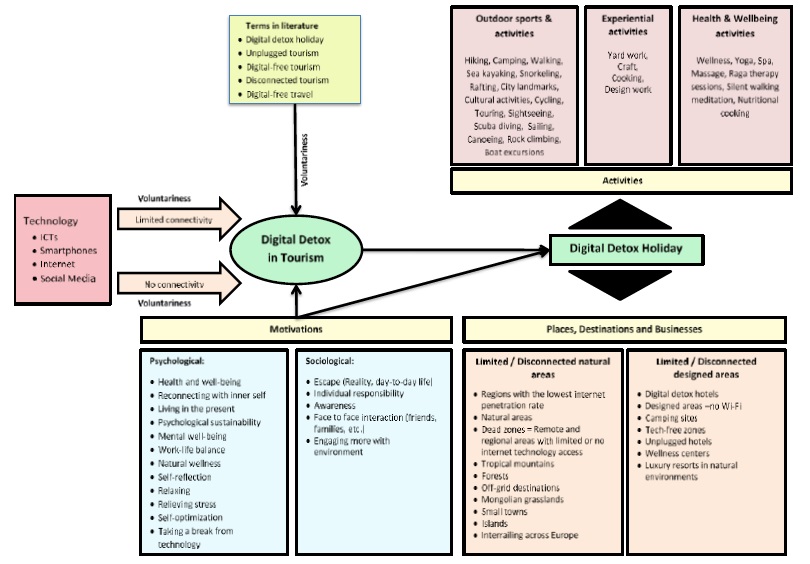

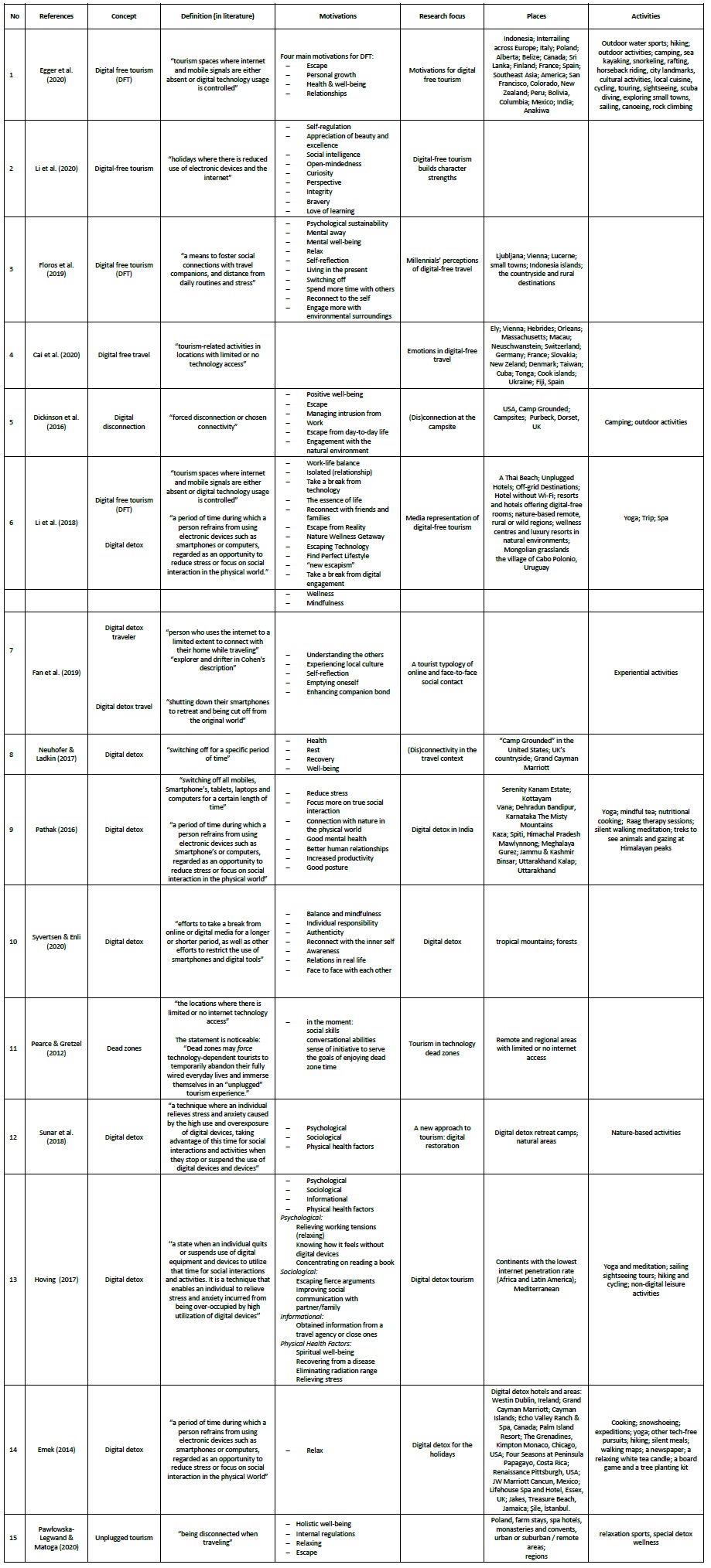

Besides bibliometric research, this study reviews tourism publications associated with the digital detox keyword to address the following questions: What is the concept of the digital detox holiday? What motivates tourists to participate in digital detox holidays? Where can tourists take digital detox holidays? What activities can they engage in? The aim is to increase understanding of digital detox in tourism and indicate directions for future research. The digital detox holiday model presented in Fig. 1 responds to these questions by identifying four essential factors from a review of 15 publications (Appendix-2): similar terms, motivations, places, and activities- to understand digital detox holidays.

Pawłowska-Legwand (2020) treats unplugged tourism and digital detox holidays as similar concepts while emphasizing that unplugged tourism is a niche market. Likewise, unplugged tourism (Pawłowska-Legwand & Matoga, 2020) and digital free tourism (Egger et al., 2020; Floros et al., 2019; Li et al., 2018) are very similar despite being defined as separate tourism types in the literature. Both refer to holidays that emphasize mental well- being and escape daily life by restricting technology use in disconnected areas. Since digital detox holiday is associated with various tourism types, the keywords in the research model are accordingly defined, and motivations are given. Whether it is defined as unplugged, digital-free, or disconnected tourism, the digital detox holiday should be voluntary and feasible by partially or entirely stopping ICT use. Any ICT use should be limited to communicating with home (Fan et al., 2019). If tourists are not aware before they arrive that their destination is disconnected or cannot use ICTs, this is not voluntary, and they may experience stress and anxiety in such dead zones (Pearce and Gretzel, 2012).

Conversely, tourists who want to take a holiday in dead zones for digital detox voluntarily travel to these regions to get away from stress and ICTs. This holiday form has been variously called unplugged tourism, digital-free tourism, disconnected tourism, and digital-free travel in the literature. However, they are not different from the digital detox holiday. Previous studies have identified psychological and sociological factors motivating digital detox holidaymakers (Appendix 2). The psychological motivational factors including improving health and well-being, reconnecting with the inner self, living in the present, psychological sustainability, mental well-being, work-life balance, and natural wellness. Sociological factors include escape from reality or day-to-day life, taking individual responsibility, increasing self-awareness, face-to-face interaction with friends, family, etc., and more engagement with the environment. Research indicates that two types of places are suited to digital detox holidays: natural areas and areas designed to have limited or no connection. Natural areas with limited or no connection are dead zones in remote areas, such as islands, small towns, Greenland, forests, far from cities, or underdeveloped countries lacking ICT connectivity. The designed areas are constructed by tourism businesses to have limited or no connection, such as digital detox hotels, camping sites, tech-free zones, unplugged hotels, wellness centers, and luxury resorts in natural environments. Tech-free places can also be designed within hotels, spas, and eco-rooms (Gretzel, 2013). Camping tourism, rural tourism, agricultural tourism, ecotourism, and adventure sports tourism allow digital disconnection (Dickinson et al., 2016), while monasteries enable isolation from daily life (Heitzman, 2013). Instead, tourists can experience the daily life of local people in workshops and participate in spiritual practices (O’Gorman & Lynch, 2008). The activities draw on concepts of balance and awareness (Syvertsen & Enli, 2020, p. 1271). There are three main types of digital detox holiday activities: outdoor sports and activities; experiential activities; and health and well- being activities. Outdoor sports and activities include hiking, camping, walking, sea kayaking, snorkeling, rafting, visiting city landmarks. Experiential activities include creative experiences, such as yard work, crafts, cooking, and design work. Finally, health and well-being activities focuson spirituality, such as wellness, yoga, spa, massage, raga therapy, silent walking meditation, and nutritional cooking.

3. Methodology

3.1 Data Source and Bibliometric Methods

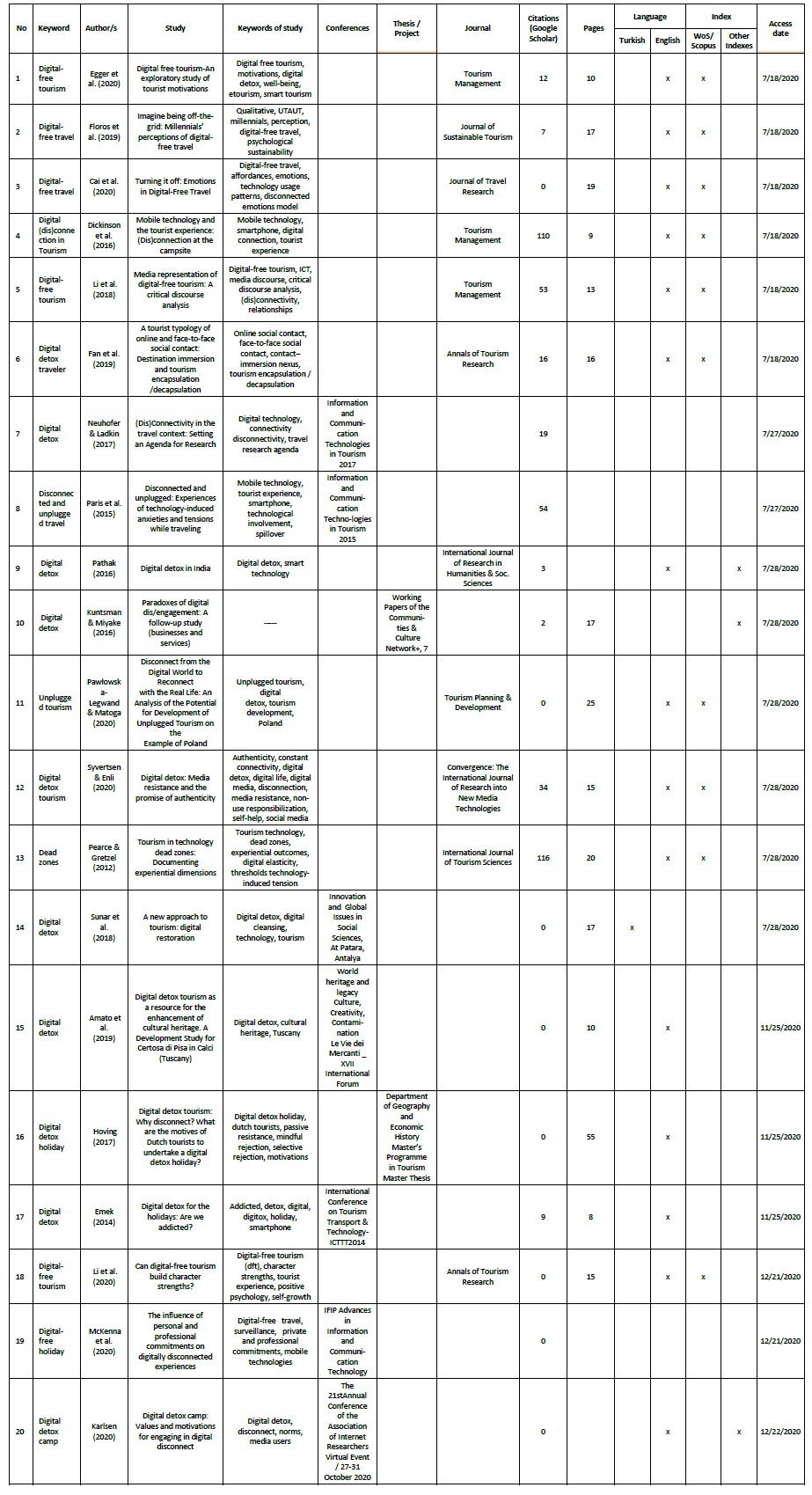

The research was conducted as follows. First, Scopus and Google Scholar databases were searched using the keywords “digital detox holiday”, “digital detox tourism”, “digital-free tourism”, “(dis)connection in tourism”, “digital detox traveler”, and “unplugged tourism”. For the Scopus database, the search used the logical operator “AND” (e.g., digital AND detox AND tourism). The publications were obtained under “TITLE-ABS- KEY”. This search included data from documents published in English or Turkish from 2012 to 2020 in social sciences, which were accessed between 18 July and 25 December 2020. As the largest databases, Scopus and Google Scholar were searched to find the limited number of publications. The search yielded only 20 publications for further analysis: 17 in Scopus and 3 in Google Scholar. Thus, this topic is not common in tourism research but offers potential for future research.

3.2 Data Analysis

Bibliometric analysis was used with selected criteria. Firstly, the characteristics of each publication were identified using the bibliometric criteria of Wang et al. (2020). The criteria were total number of publications (TP), total number of citations (TC), number of non-international cooperation (NNIC), number of international cooperation (NIC), number of single institutions (NSI), number of multiple institution cooperations (NMIC), number of single authors (NSA), number of multiple authors (NMA). The characteristics and content of all 20 publications were described in detail in bibliometric tables. The analysis also identified the most cited publications, the countries and authors with the most citations, and the most productive institutes and journals. Secondly, VOSviewer, a mapping visualization tool to create network and density charts, was applied to the 17 publications from Scopus. VOSviewer enables analysis of co-authorship network and co-occurrence of keywords, considering the following limitations: co-occurrence, author keywords, and the minimal number of keyword occurrences in the names, keywords, and abstracts of the publications. The visualization analysis produced a co- authorship network map and co-occurrence map of keywords. The co-occurrence map of keyword terms represents how often two terms co-occur in a series of publications.

4. Results

The results of the bibliometric analysis of the 20 publications collected from the Scopus and Google Scholar databases (Appendix 1) are presented below in terms of the characteristics of publications and science mapping analysis.

4.1 Characteristics of publications

The publications were examined in four aspects: an annual analysis of publications, the most cited publications, the most productive institutions, and the most productive journals.

4.1.1 Annual analysis of publications

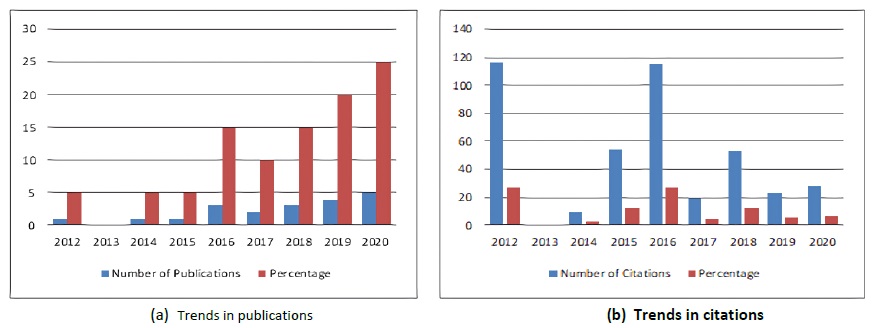

Figure 2 shows changes in the number and percentages of publications and citations from 2012 to 2020. As Figure 2a shows, the number of publications per year generally increased from less than two for the first five years after 2012, with more than three publications per year from 2016 to 2020. The increase in 2019 indicates that more researchers were becoming interested in digital detox holiday research. Although the number of studies decreased between 2012 and 2016, it increased after 2016. Especially since 2018, the number increased and is likely to continue growing. Figure 2b shows the distribution of citations. The most citations (116) appeared in 2012, followed by 115 citations in 2016.

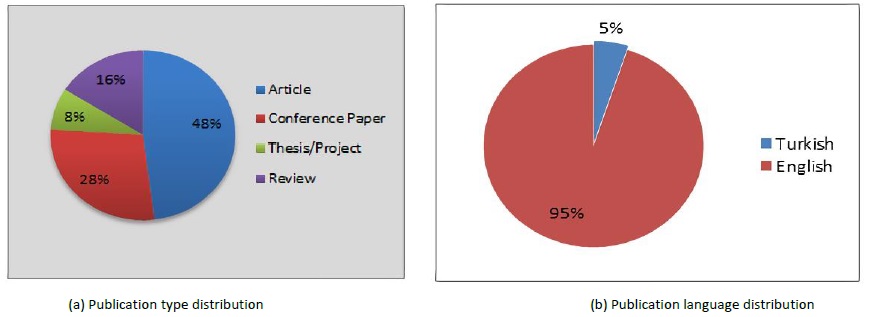

Considering type of publications, nearly half of the publications were articles (48%), followed by conference papers (28%), reviews (16%), and theses and projects (8%) (Figure 3a). Most publications were in English (Figure 3b).

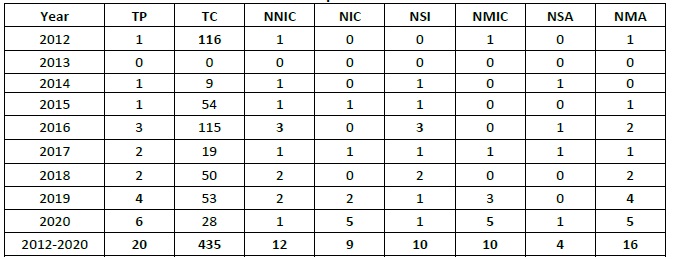

Table 1 presents annual changes in the characteristics of publications between 2012 and 2020. The maximum value of each indicator is highlighted in bold. There were more publications with multiple authors than single authors, especially after 2018. There were 438 citations between 2012 and 2020, with the most (116) in 2020 following increasing numbers after 2016. The year with the most publications (5) was 2012. These findings indicate growing research interested in digital detox since 2016.

Table 1 Annual characteristics of publications between 2012 and 2020

TP: Total number of publications; TC: Total number of citations; NNIC: The number of non-international cooperation; NIC: The number of international cooperation; NSI: The number of a single institution; NMIC: The number of multiple institution cooperation; NSA: The number of single-author; NMA: The number of multiple authors.

Regarding cooperation, international cooperation (NIC) was more common than local (NNIC). The most local cooperations (3) were in 2016, while the most international collaborations (4) were in 2020. While there were more local than international cooperations in 2016, there were far fewer by 2020, which indicates a growth in international collaboration in publications, which is likely to increase in the future.

Regarding institutional cooperation, there were ten instances of both single-institution and multiple-institution publications. Since 2018, the latter has been more common, particularly in 2020, indicating strong research cooperation between institutions for digital detox holiday publications. Similar to NIC, NMIC has increased since 2019. NSI was more than NMIC until 2019, but NMIC then increased. This indicates that more researchers from different institutions will research digital detox holidays. More publications were written by multiple authors than single authors, indicating that researchers prefer to work with multiple collaborators in this area.

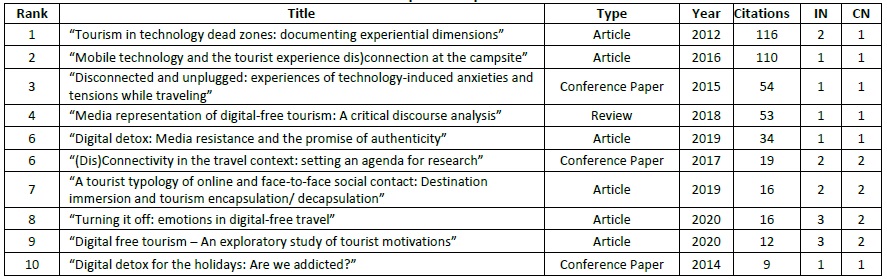

4.1.2 The most cited publications

Most of the publications did not deal solely with digital detox holidays but included the concept, among others. Table 2 lists the top 10 publications in terms of type, year, and number of institutions (IN) and countries/regions (CN) involved. Of these, 6 are articles, 3 are conference papers, and 1 is a review. The two most cited are articles (Dickinson et al., 2016; Pearce & Gretzel, 2012), which both investigated the experience of ICT disconnection and emotional resistance to it, which were widely studied topics between 2012 and 2018. After 2018, however, the research focus changed towards motivations and categorizing digital-free tourism and digital detox. Half of the publications in Table 2 are by multiple institutions, three have two institutions, and two have three institutions. Notably, the publications in 2020 were produced by three institutions from two countries. Wang et al. (2019) argue that institutions and countries or regions need to collaborate to produce highly cited publications, although the citation rates found in our study may also be influenced by the low number of studies on this subject.

Table 2 Top 10 cited publications

IN: Number; of institutions CN: Number of countries/Number of regions.

The countries that got the most publications related to digital detox in Scopus are the UK and Australia, while the countries that got the most cited publications are Australia and the UK. The two authors with the most publications on digital detox holidays were Li J. (3) and Pearce P. L. (2). They also had the most citations, with 26 and 25, respectively. While Low, Berger, Casson, Paris, and Rubin all had just one publication each, Low’s publication received 25 citations compared to 23 for all the others combined.

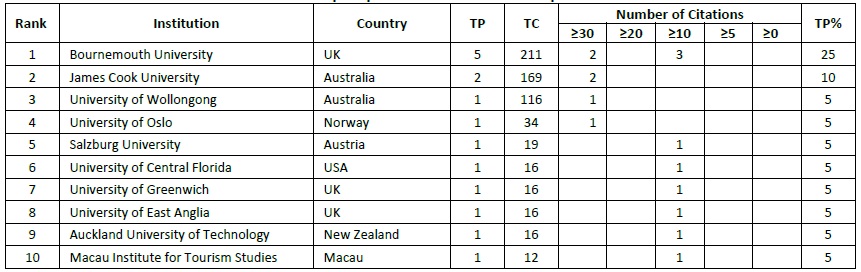

4.1.3 The most productive institutions

Table 3 lists the ten most productive institutions out of a total of 293. The most productive was Bournemouth University (UK) with 25%, followed by James Cook University (Australia) with 10%. The top 10 most productive institutions are all from island or coastal countries, except for Austria. This suggests that institutions from these types of countries have a stronger interest in digital detox holidays. Regarding citations, the top four institutions all had more than 30, with Bournemouth University being the most influential institution with 211.

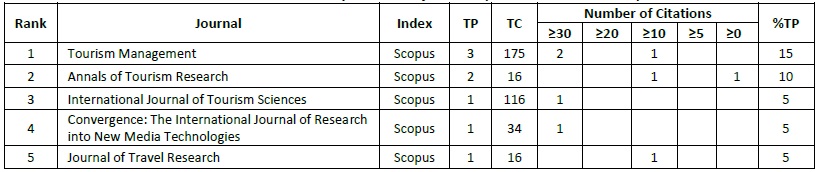

4.1.4 The most productive journals

Table 4 shows the top five productive journals regarding the number of articles (TP) and citations (TC). Tourism Management (15%) and Annals of Tourism Research (10%) published the most articles, while the most cited journals were Tourism Management (175) and “International Journal of Tourism Sciences (116). The top five journals indexed by Scopus were Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, Annals of Tourism Research, and Journal of Travel Research, which had 34, 16, and 16 citations, respectively. Thus, they have more citation potential than other journals. Given the growing attention of researchers since 2018, more studies on digital detox holidays are likely in the future.

4.2 Science mapping analysis

VOSviewer was used to conduct scientific mapping analysis (co- occurrence analysis, co-authorship analysis, and network map of abstracts) for 17 publications from eight countries in Scopus.

4.2.1 Co-occurrence analysis

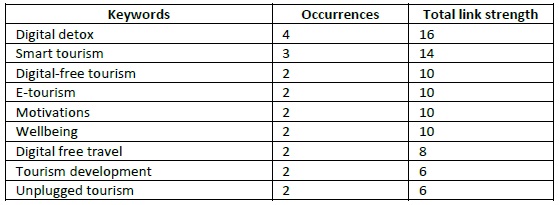

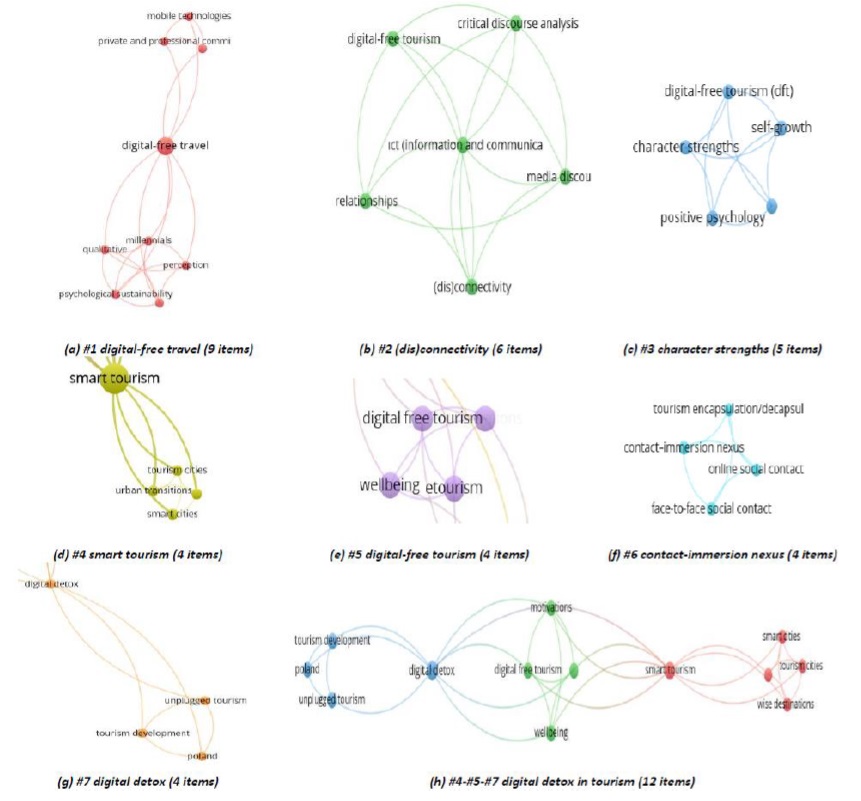

The co-occurrence analysis of keywords is an effective tool for understanding knowledge structures and research trends to understand primary and secondary publications. The node size represents the number of publications, while the line between two nodes represents a link between the two clusters. The shorter the line is, the stronger the link is. A link means a co- occurrence between the two keywords (Guo et al., 2019, p. 14). The following keywords were used in this study: “digital detox holiday”, “digital-free tourism”, and “unplugged tourism”.

Using VOSviewer, the 17 publications between 2012 and 2020 were evaluated using 37 keywords that met the minimum keyword occurrence number of 1, with no search time limit. Some of the 37 items were not connected, while the largest set of connected items had 13 items. Seven clusters of co-occurring keywords were identified (Figure 4a-g). Each cluster represents a keyword and shows the most linked and repeated keywords in the publications. All clusters have a different color for the visualization analysis with each color emphasizing one keyword: red = digital free travel; green = (dis)connectivity; blue = character strengths; yellow = smart cities; purple = digital-free tourism; turquoise = contact-immersion nexus; orange = digital detox. Because there were few studies, the number of co- occurrence links between keywords was not high. As Figure 4h shows, three clusters had a stronger relationship: digital-free tourism, digital detox, and smart tourism.

Figure 4 Network map of co-occurrences of digital detox holiday, digital-free tourism, and unplugged tourism in publication titles, keywords, and abstracts

#1- digital-free travel includes nine items: mobile technologies, private and professional communication, millennials, perception, qualitative, psychological, and sustainability. #2-(dis)connectivity contains six items: digital-free tourism, critical discourse analysis, ICT, disconnectivity, relationship and media discourse. #3- character strengths includes 5 items: Digital-Free Tourism (dft), self-growth, character strengths, positive psychology, and tourist experience. #4- smart tourism includes four items: wise destinations, smart cities, tourism cities, and urban transitions. #5- digital-free tourism includes 4 items: DFT, well-being, etourism, and motivations. #6- contact-immersion nexus includes 4 items: online social contact, contact- immersion nexus, face-to-face social contact, and tourism encapsulation/decapsulation. #7- digital detox includes 4 items: unplugged tourism, tourism development, Poland, and digital detox.

Figure 4h shows a network of co-occurrences of the three main clusters (12 items): “digital-free tourism”, “digital detox”, and “smart tourism”. Digital detox, which has the most links, is most closely related to digital-free tourism, motivations, well-being and etourism. Digital free tourism acts as a bridge between digital detox and smart tourism. The analysis shows that the digital detox holiday is a new concept associated with digital- free tourism and linked to “unplugged tourism”. That is, the keywords for digital detox holidays are mostly mentioned in publications about digital-free tourism.

Table 5 summarizes the occurrences and link strengths of the nine clusters among all publication keywords. That is, these are the top nine most repeating and occurring keywords which had six and more links examined by VOSviewer visualization analysis.

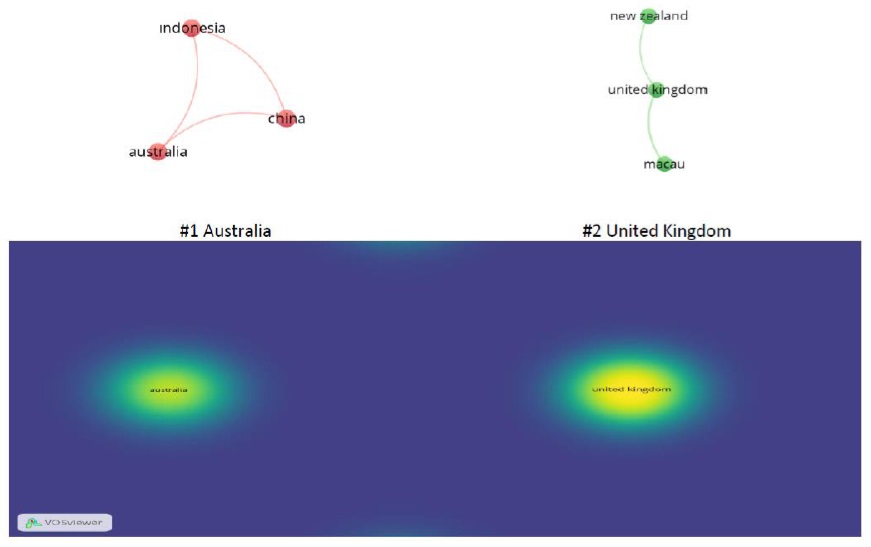

4.2.2 Co-authorship analysis

The visualization analysis revealed eight countries based on the criteria of one publication for each country while 29 authors and 6 thresholds were obtained from the co-authorship analysis. Two clusters were formed for publications between 2019 and 2020 showing the collaboration of six authors (Figure 5). The six countries in the two clusters were distinguished by color: red (#1 Australia) represented the co-authorship networks of Australia, China, and Indonesia; green (#2 United Kingdom) represented the co-authorship networks of Macau, United Kingdom, and New Zealand. Thus, each cluster indicates which authors from which countries collaborate. The UK has the strongest links, with 3 links and 5 publications.

Two sets of researchers had the strongest co-authorship links regarding publications on digital detox holidays: Cai, Mckenna and Waizenegger (2020) and Floros et al., (2019).

5. Conclusion

This study explored digital detox holidays as a new tourism form by reviewing and bibliometrically analyzing publications related to this topic. It provided new knowledge about research into this concept, particularly the characteristics of publications, and answered several questions regarding where, how, and why digital detox holidays take place. Fifteen publications (Appendix 2) were reviewed to identify motivations, places and activities related to digital detox holiday were further reviewed to reveal digital detox holiday model; second, 20 publications about digital detox holidays, identified from keyword searches of Google and Scopus, were examined using bibliometric analysis while the 17 publications retrieved from Scopus were also analyzed using VOSviewer.

The study makes several theoretical contributions. First, it offers a digital detox holiday model (Fig. 1) that identifies and defines concepts related to motivations, places, activities, and uses. By describing digital detox, the model draws together closely similar terms in the literature, such as unplugged tourism, digital free tourism, disconnected tourism, and digital free travel. In particular, digital free tourism (Egger et al., 2020; Floros et al., 2019; Li et al. 2018, 2020), digital disconnection (Dickinson et al., 2016), digital free travel (Cai et al., 2020), unplugged tourism (Pawłowska-Legwand and Matoga, 2020), and digital detox travel (Fan et al., 2019) have mainly similar features. Of these, digital free tourism and unplugged tourism include the concept of digital detox holiday, which follows earlier conceptualization (Cai et al., 2020; Egger et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2019; Floros et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Pawłowska- Legwand & Matoga, 2020), defining digital-free tourism and unplugged tourism as “voluntarily sought experience, rather than as an inconvenience of travel”, and the definition of Syvertsen (2020) of digital detox as an effort to take a break from online or digital media for a temporary period. More specifically, our study shows that digital detox holiday is a new tourism form. That is, it is a tourism form with limited or no ICT connection that depends on individual preference and willingness. We can consider digital detox holiday as a form of digitally free tourism, or unplugged tourism (Pawłowska- Legwand & Matoga, 2020), who argue that the severe disadvantages of using ICTs has stimulated the growth in digital detox holidays and unplugged tourism. The psychological and sociological factors are similar to those mentioned by Egger et al. (2020), motivating individuals to participate in disconnected or limitedly connected tourism, such as digital detox holidays. Such temporary escapes from daily lifestyle help tourists detoxify. They may go to ICT limited or disconnected areas, whether natural or designed, to participate in outdoor activities, experiential activities, or health activities. In short, a digital detox holiday is a form of temporary tourism spent in the natural or designed areas with limited or no ICT connectivity that individuals choose voluntarily to escape from the stress of daily life and excessive ICT use. Second, the study brings a perspective to tourism research on being disconnected. These publications examine the new topic of digital detox holidays. Accordingly, the number of publications has increased since 2016, especially since 2018, and seems likely to grow further in the future. The most cited publications were written in 2012 and 2016. The publications are mostly articles in English, written by multiple authors with non-international cooperation. However, international cooperation may increase in the future. The number of publications with multiple authors has increased since 2018, while multiple institution cooperation was highest in 2020. There is increasing cooperation between institutions in research on digital detox holiday, indicating that more institutions will research this topic in the future than before.

The two most cited publications were Dickinson et al. (2016) and Pearce and Gretzel (2012), while the UK and Australia produced the most publications. Of these two, Australia had the most citations. The two most published authors were Li and Pearce, who were also the two most cited. The two most productive institutions were Bournemouth University (UK) and James Cook University (Australia). The top ten productive institutions all came from island or coastal countries, except for Austria, indicating their strong interest in digital detox holidays. The two most cited journals were Tourism Management and International Journal of Tourism Sciences. The relationship of digital detox holidays to disconnection in tourism has recently gained increasing research interest, particularly since 2018, suggesting that research on this topic will increase further in the future.

Third, this study explored publications on Scopus using VOSviewer. The keywords of 17 publications were examined between 2012 and 2020, although there was no time limit in the search. The search included 37 keywords that met the threshold of one occurrence. While some keywords in the network were not connected, three main clusters were identified: digital-free tourism, digital detox, and smart tourism. The digital detox keyword, which had the most links, was most closely related to digital-free tourism, while digital-free tourism acted as a bridge between digital detox and smart tourism. Digital detox holidays, as a new concept was associated with digital-free tourism, and in combination with unplugged tourism. That is, the keywords for digital detox holidays mostly appeared in publications on digital-free tourism. There were two country clusters of publications between 2019 and 2020 with the collaboration of six authors. Australia (Australia, China, and Indonesia) and the UK (Macau, the UK, and New Zealand) had the most co-authorship networks in their clusters. The publications by Cai, Mckenna, and Waizenegger (2020) and Floros, Cai, McKenna, and Ajeeb (2019) had the most co- authorship links related to digital detox holidays.

This study also has several practical implications. First, tour operators and accommodation businesses have become interested in digital detox holidays recently and offer various products for disconnected and limitedly connected areas. As Pawłowska-Legwand and Matoga (2020) note, tourism in disconnected areas can become a niche market. Second, the research model developed for this study can help tourism providers identify motivations, places, and activities regarding digital detox holidays. This model can help tourism service providers better supply tourists’ needs. Third, as Egger et al. (2020) point out, mental health and wellness experts see a need for disconnection and can suggest digital detox holidays as a tool. Finally, our results and previous studies indicate that it is more realistic for tourism destinations to restrict the use of ICT rather than eliminate it entirely.

5.1 Limitations and Future Research

This study has three limitations. First, a review and bibliometric research analyzed the available publications accessed between certain dates from just the Google and Scopus databases. This is the main limitation of this study, intended only to provide a framework for future studies. Second, the study used only a limited set of keywords to identify scientific publications on digital detox holidays. Finally, since the research was bibliometric, its practicality is limited. Future studies can investigate digital detox holidays in terms of practicality, especially in the design of accommodation businesses and their marketing in tour operators’ holiday packages. In addition, more research is needed regarding tourists’ experiences of visiting disconnected areas voluntarily.