1. Introduction

Although tourism is recognized as a major industry worldwide, “an activity of global importance and significance” with great impact upon economies, the environment and societies (Cooper, Fletcher, Gilbert, Fyall & Wanhill, 2005, pp. 4-6) it is not yet accessible to all. Senior tourism is a type of tourism within social tourism, since seniors are considered as one of the groups who may be excluded from the tourism experience. Social programmes are integrated into social tourism and emerged as a way to democratize the tourism experience, making it accessible to individuals or groups with some limitation or difficulty of access (Cheibub, 2012 cited in Oliveira et al., 2019). In fact, this is the case of seniors, in addition to people with disabilities, young people and those with low income.

The United Nations (2017, cited in Lewis & D’Alessandro, 2019) has identified ageing as a significant social transformation of the twenty-first century, making the senior tourism segment lucrative due to its size and growth potential. According to Lopes (2018), today's society has a unique demographic phenomenon, reflected in the ageing of the global population. Various changes, mainly in developed countries, such as the decline in birth rates and the increase in life expectancy, as well as advances in medicine and improvement in the living conditions of the population, are the main factors behind this. Due to this demographic and social phenomenon, “the senior population is of interest to the tourism industry because of its growing size and increasing participation in travel activities” (Huber, Milne & Hyde, 2018, p. 55) and its influence on tourism markets is already becoming evident, with infrastructure and services feeling the need to adapt to this situation.

Senior age is accompanied by various changes - physical, psychological and social - which affect the ability to explore opportunities to participate in tourism activities (Huber et al. 2018). In addition, other constraints like lower income and poorer health conditions also affect seniors’ participation in tourism. Because of that, it is important that leisure activities (such as tourism) are made accessible in order to give opportunities to all. For that reason, specific social tourism programmes are offered in order to encourage the participation of senior citizens in tourism, since “by enhancing their knowledge of senior tourism, the tourism industry, destinations, and policymakers will be better prepared for the forthcoming demographic challenges” (Huber et al., 2018, p. 56).

The research behind this article is based on elderly people who are institutionalized in nursing homes. Considering the particular characteristics of this group, the VOLTO JÁ project was created to allow these citizens access to tourism experiences. This project carries out a set of actions which impact directly on seniors’ mobility and social exclusion. With the VOLTO JÁ project, this group of people, the elderly, have the opportunity to have an experience in a recreational context, and for some of them, this will be their first time doing so. Based on clear objectives covering the dimensions of social innovation and community development, this project has various activities, among which the design of tourism packages for elderly people within senior exchange programmes and also the evaluation of tourism experiences stand out.

The main purpose of this article is to better understand senior tourism experiences based on the VOLTO JÁ project as a case study and its general objectives are: (i) exploring the main concepts under study related to senior tourism; (ii) exploring a particular senior market segment that will lead to an accurate market segmentation (in this case, institutionalized seniors from the social institutions participating in this project), and (iii) the planning, design and proposal of social tourism packages. The specific objectives are the following: i) to describe a framework about basic concepts such as social tourism and senior tourism, social tourism, senior tourism motivations and tourism experiences; ii) to present the VOLTO JÁ project mission and activities as a case study; and iii) to present a proposal of a conceptual framework (model) for packaging and experience evaluation based on the VOLTO JÁ project, specifically the results from stage one and three of the model’s implementation. This article may contribute to reinforcing the conceptual framework to research the behaviour of the elderly, and from an applied perspective within a single case study. It may be useful to develop specific future experiences for a specific population within elderly institutionalized people.

2. Senior tourism and travel motivations of seniors: theoretical background

2.1. Senior tourism

Considering demographic changes in modern society, seniors are projected to be one of the most important segments for the tourism industry (Otoo & Kim, 2018). Over the past decade, leisure travel has become more popular in older segments as a consequence global factors such as rise in life expectancy, better health conditions, higher disposable income and more availability of discretionary time in retirement age (Patuelli & Nijkamp, 2016). In fact, senior tourism presents a market with significant potential.

So, there is an evident relationship between sociodemographic characteristics of senior tourists and travel motivation. Still, research about senior consumer behaviour intentions remains insufficient (Moniz, Medeiros, Silva, Ferreira, 2019), but it has gained increased attention from tourism researchers as well as from service providers and governments (Patterson & Balderas, 2018).

There is no exact definition of senior tourism in part because it is a heterogeneous market and older consumers are not all alike (Lehto et al. 2002, cited in Patterson & Balderas, 2018). Also, the concept does not end at the single dimension of age, but it is one of the most important criteria.

Regarding age stratification, based on Alén, Dominguéz & Losada (2012, pp. 142-143):

Seniors (aged 55 years or older) and non-seniors (under 55 and older than 15); segmentation of the elderly has to be made into two younger elderly subgroups, 55 to 64 years old and the elderly, 65 years old or more.

Elderly tourist - over 65 years old;

Elderly - individual over 50 years of age;

Senior tourist - over 55 years old;

Senior tourist - 60 years old or more;

Elderly tourist - between 65 and 74 years old.

Hossain, Bailey and Lubulwa, (2003, cited in Alén 2012) say that seniors are those 55 years of age or older, and non-seniors are those under 55 but over 15 years of age. They segment seniors into two subgroups: younger seniors, from 55 to 64 years old and older seniors, 65 and older. According to Tomka, Holodkov and Andjelković (2015, p. 63), the definition of a senior tourist could be: (i) retired persons aged 60 who have more money and time to travel or are nearing retirement, but are still employed due to local regulations; (ii) sociological golden age or a tourist with an “empty nest” (no family obligations or care for offspring), and (iii) those that are normally passive tourists and are, as such, psychocentric.

Moreover, Alcaide (2005 cited in Alén et al, 2012) states that some companies set the senior age break at 55 years. According to this perspective, this is the age at which the consumer begins to sense different needs and forecast and plan for ageing; they are considered as part of the segment of the elderly in the banking system, which begins to differentiate and specialize treatment for them. “Other companies set the boundary at 60, the age that marks the differentiation between older people and the mature, and begin to consider the possibilities of offerings that are appropriate to the interests and realities of this group” (Alén et al. 2012, p. 143).

However, age alone cannot determine a whole segment, making it essential to attend to issues such as consumer behaviour, given their physical and mental condition. This idea is justified with the premise that tourism for the elderly is represented by people over 60, self-sufficient both physically and cognitively and with time and financial resources to travel, visit and enjoy a tourist destination (Alén et al., 2012).

Senior tourism in the new panorama of social and business management can undoubtedly be taken as a growing and constantly evolving sector and, as already mentioned, much research has been undertaken in order to unravel its specificities. Ridderstaat (2015) concluded that the senior tourist is not a standard tourist, since tourists have specific preferences and codetermined motivations where aspects such as favourable climatic conditions, accessibility, cultural facilities and even less popular places are valued, thus contributing to reducing seasonality in certain contexts.

The concept of senior tourism alongside other types of tourism has evolved throughout its history, influenced by social, political and cultural contexts and environments. It sustains its credibility as an important and proven agent of change, which still needs to be explored and consolidated at corporate and institutional levels.

This situation undoubtedly represents a business opportunity; one only needs to look around and realize that in different parts of the globe, populations are increasingly ageing, with much of the responsibility resting on advances in medicine. According to Le Serre (2008), the senior tourist segment represents a profitable source of revenue for companies linked to the tourism sector, not only because of its growing size, characterized by the continuous ageing of the world population, but also due to availability and time to travel. “As with any new tourism phenomenon, motivation is an integral first step in exploring the prospects of the senior tourism segment. Continual research on senior tourists’ motivations reveals varying types of motives for which the elderly pursue travel” (Otoo & Kim, 2018, p. 2).

2.2 Social and accessible tourism

Social tourism and accessible tourism have a relationship with senior tourism and with elderly people. First, social tourism presents a practice with great potential, but scarce research. What is sought with this typology is to make tourism a vehicle for access for all, regardless of their social condition or economic context. It is imperative to use tourism as a factor of social inclusion, and to allow travel to be accessible to the largest possible number of people, respecting the individual potential of each person and providing benefits of different orders from the economic, cultural and social.

In a broader sense, tourism is conceived as a means of promoting and sharing knowledge, where tourists acquire stimuli through contact with other situations. As argued by Ferreira and Tomé (2014, p. 209, cited in Piedade, 2017, p. 25), “tourism inevitably produces socio-spatial changes, insofar as it reorganizes the territory and establishes new uses (…) these transformations can be greater or lesser, creating social inclusion or exclusion depending on the way it is planned”. It is of utmost importance to teach and inform societies about this new paradigm, in which inclusion and access to leisure practices are not yet a reality for everyone, and only through this recognition can people be made aware of the differences and the need to combat these asymmetries.

According to Piedade (2017, p. 26) “… social tourism becomes an instrument for promoting socio-positive relationships between people of different cultures, of different levels of socialization, being a dynamic element in the sharing of valuable experiences for development political and socio-cultural dimensions”. For this practice to become sustainable, one cannot depend only on local power, but also on interpersonal relationships, where local communities can be the link between the tourist and the destination, allowing their integration.

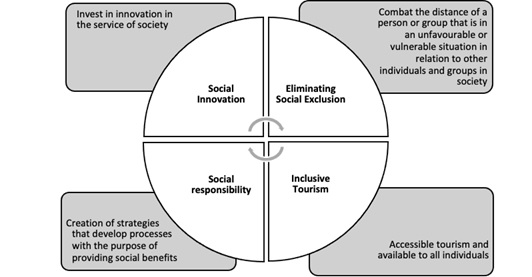

Silva (2018), also argues that it is mandatory to conceive social tourism as an opportunity to leverage and enhance the social sector; it is necessary to look at this practice based on a concept of inclusion, opportunity, solidarity and above all cohesion. The author also expresses social tourism as an opportunity to democratize access to that segment of the population with fewer financial resources and still contribute to combating seasonality in the activity, to foster networking and the creation of institutional partnerships. It can also make a great contribution to local economies, considering that social innovation today must be seen as a distinguishing factor of success (Silva, 2018). This raises new questions, namely the need that entities in the sector will have to face, that is, the necessity to reinvent themselves while creating value, generating wealth and reinforcing territorial cohesion. In line with this, Lima (2017) assumes that social tourism should be tourism for all and should be seen as an act of social responsibility and argues the concern to think and rethink inclusive strategies emerges in order to cover the most disadvantaged segments of the population in tourist activity. Figure 1 shows the dynamics of social tourism based on the literature review.

Senior tourism is also directly linked to accessible tourism because disability is often directly related to the elderly (Alén et al., 2012). Considering the perspective of tourism for all, integrated into social tourism and accessible tourism standpoints, all tourists can be active participants in the tourism sector, regardless of their characteristics, abilities and needs. In this case, social tourism was created with the objective of making leisure tourism available to a broad segment of the population promoting “leisure and conviviality among disadvantaged groups, in fact providing resources to those groups with limited resources - the elderly, young people or people with different abilities - in order to allow them to travel with the appropriate conditions of economy, accessibility, safety and comfort” (Alén et al., 2012, p. 145).

2.3 Travel motivations of seniors

According to Nella and Christou (2016), the continuous monitoring of market trends is one of the most important roles that marketing scientists and practitioners should fulfil. As is well known, tourism is significantly affected by major demographic cultural and economic trends, and this responsibility becomes crucial for destination marketers and other tourism marketers. Thus in this context (Sedgley, Pritchard & Morgan, 2011), it is not surprising that the tourism industry has recognized the market potential of older people and tourism research has tended to focus on developing competitive business and marketing strategies to target these consumers, mainly concerning their motivations.

The senior tourism market can have a positive impact on seasonality since it provides a solution to bridging the gap between lean and peak destination seasons. On the other hand, concerning the socio-personal perspective, travel contributes to the improvement of quality of life and promotes active ageing (Otoo & Kim, 2018). Also according to these authors, in an overview of the senior travel motivation literature, it is possible to sum up some perspectives:

Sie et al. (2016) focused on the educational travel experiences of older adults; six broad experiences of older adults were identified: refreshment, socialization, bonding time, intellectual experiences and self-fulfilment, nostalgia, and health and physical fitness;

Patuelli and Nijkamp (2016) identified the key senior motives of travel culture/nature, experience/ adventure, relaxation/well-being/escape, socialization, and self-esteem/ego-enhancement.

There is no agreement regarding the classification of senior travel desires. However, they can be categorized in four groups (Otoo & Kim, 2018, p. 17):

Indulgence motivations: this refers to motivation that requires an individual to commit to pleasure-seeking behaviour. It includes socialization, rest and comfort, hedonism, and escape motives;

Supra-personal motivations: presence of quality facilities or services, travel opportunities, or other destination attributes (which transcend intrapersonal or intrinsic desires);

Status motivations: desire to travel for achievement or egotistic reasons (e.g. ego or esteem, actualization and novelty);

Drive motivations: psychological needs which can be satisfied within a single or successive travel experience.

According to Tomka, Holodkov and Andjelković (2015, p. 64), based on international research with the “third age”, the authors identify eight factors of travel as beneficial for the elderly: excitement, family ties, self-development, physical activity, safety, social status, escape from everyday life and relaxation. Another referenced study points out two categories of motivations: i) external prerequisites, which include social advancement, adequate personal financial means, time, health condition, support of senior’s family to travel and responsibility, as well as the wish to travel; ii) internal wishes that include the improvement of well-being, constant removal displacement, socialization, knowledge resulting from visiting a new destination, pride, patriotism, personal gain and nostalgia in the broadest sense. It is possible to make a comparison between senior and other travel segments and the authors Otoo & Kim (2018, p.18) come to these conclusions:

Travel motivation sets, such as indulgence and status, are common for senior tourists, as well as for other travel segments;

Nostalgia motivation for seniors generates personal meaning which is only realized at an older age;

Seniors require tailored information services and convenient transportation.

2.4 Senior experience and consumer behaviour

A global demographic shift is leading to an increasing number of older citizens and senior tourism is becoming more important worldwide. The senior market has gained increasing interest from the tourism industry, mainly because of its considerable size and time flexibility (Carneiro, Eusébio, Kastenholz & Alvelos, 2013). For that, it is important to understand the profile of this type of segment, according to their travel behaviour. In segmenting the market, considering motivations, some of the literature considers older people in various marketing groups using demographic and psychographic data; lifestyle and attitudinal factors; educational and income levels; and even housing type and ownership (Sedgley et al., 2011).

There are different factors that influence the behaviour of this type of traveller. For instance, Huber, Milne and Hyde (2019) conclude that life events can have a strong impact on senior tourism behaviour, since they can interrupt existing travel patterns or prompt new ones. From a different perspective, Hwang and Lee (2018) designed a study to identify the important role of tour guides’ professional competencies in the senior tourism market, concluding that travel agencies should educate tour guides to understand the characteristics of senior tourists. Carneiro et al. (2013) also conclude in their study that promoting activities that encourage involvement with the local community and contact with nature is important when developing social tourism programmes for the senior market. These are some examples of different approaches that have been undertaken when studying this type of market: (i) studies that focus more on the pre-visit behaviour, trying to better understand the factors that influence the behaviour of this segment; (ii) studies that focus on factors after the visit has taken place, particularly in terms of satisfaction.

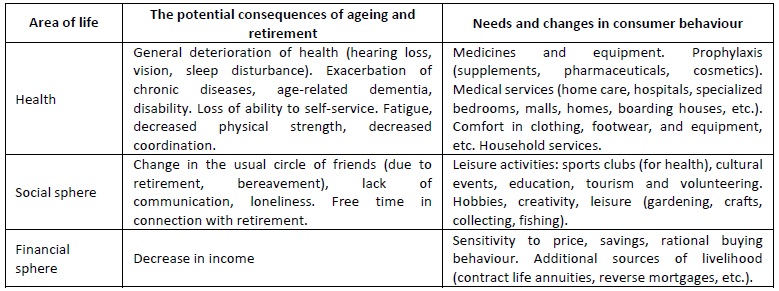

This type of market is highly characterized by people looking for unique experiences which are adapted to their rhythm and their time and which allow them a more direct and consistent contact with the local population and bring back many of their past experiences to them. Thus, this type of tourism is entirely conditioned by the expectations of the senior tourist, despite their motivations, and also by their physical and social conditions. The following table presents a general characterization of consumer behaviour in the senior tourism segment:

Table 1 General characterization of senior tourist consumer behaviour

Source: Nikitina & Vorontsova (2015, p. 851).

Undoubtedly, this tourism practice brings with it a certain rejuvenation in the values and lifestyles of this layer of the population. But in some contexts, older people are still a little apprehensive about more innovative tourism practices, favouring more conservative tourism activities that inspire greater confidence. This type of tourist is “also loyal to a travel formula, identified by a type of travel and accommodation, a thematic motivation, the involvement of fellow travellers and social identification, at bottom far more psychocentric than allocentric” (Cavaco, 2009, p. 44). However, one should never disregard their requirements and their demands; with an increasingly diversified and qualified offer of experiences, this market segment is also motivated to enjoy unique experiences that increase their quality of life and in some cases give them back their self-esteem and stimulate their active ageing.

There is some literature that attends to classifying different types of older tourist and it is not easy to establish one unique label. Kim, Woo and Uysal’s study (2015, p. 465) concludes that “the elderly tourist market is not one large homogenous group but rather that it can be segmented into smaller homogenous groups based on reasons for pleasure travel”. In this line of thought (You and O’Leary, cited in Sedgley et al., 2011, p. 3): i) there are three groups of older tourists, ‘passive visitors’, ‘enthusiastic go-getters’ and ‘cultural hounds’; ii) another classification includes (Kim, Wei & Ruys, 2003): ‘active learner,’ ‘relaxed family body,’ ‘careful participant’ and ‘elementary vacationer’, among others. In this context, it is important to consider that “the dominance of such approaches to understanding the lives of older people has meant that the nature and quality of their tourism experiences, particularly the meaning and value they attach to travel has been underserved” (Sedgley et al., 2011, p. 4). Therefore, this paper advocates that it is important to understand more deeply the opinions, perceptions and feelings of elderly tourists, not only before their experience, but also during and after (i.e. the whole process).

In this context, evaluating seniors’ tourist experience and their travel behaviour constitutes a major topic (Kim, Woo & Uysal, 2015). In a demand-side approach, ideas such as “multi-sensory, fantasy, emotions and feelings”, “high levels of emotional intensity”, “constant flow of thoughts and feelings”, “consuming is engaging in tourism experiences”, “primarily seek and consume at destinations is engaging experiences”, “long-term memory” and “experience interrupts daily lives” have been used to define a tourism experience (for more information see Amaral & Rodrigues, 2019). Therefore, several dimensions of a senior tourism experience should be considered (e.g. involvement, perceived value, leisure life, satisfaction with trip experience, overall quality of life and revisit intention) (Kim, Woo & Uysal, 2015). This information will enrich the knowledge of the elderly tourism market through an understanding of their behaviours. Concurrently, travel preferences, perceptions and opinions vary between younger and older age groups and because of that it seems appropriate to evaluate the senior experiences and the dimensions that constitute this construct (e.g. health, personal safety, language, type of information, transport and accommodation, among others) (Batra, 2019). This is also argued by Quan and Wang (2004), who state that for a better understanding of the tourism experience concept, one should define and study the main dimensions. Finally, studies about tourist satisfaction (e.g. Kozak, 2001) demonstrate that all the attributes of a destination or a package (e.g. accommodation, transport, cleanliness, facilities & activities and relationships between tourists, among other examples) are important for an overall assessment of the satisfaction of the tourist experience. This should also be applied to the senior tourism market.

In order to better comprehend what the most appropriate marketing strategies for this type of segment are, this paper advocates taking a more integrated approach into consideration: the supply- and demand-side approach. Regarding the former, travel agents or other stakeholders involved should pay attention to the process of designing appropriate programmes or experiences for this type of segment. For instance, due to the particularities of this segment, inspection visits to the places where the programme will take place are of utmost importance in order to evaluate the tourism components to be included (quality and type of accommodation; location and accessibility of museums, churches, restaurants; type of transportation; and professionalism of tour guides). Observations in loco by the supply side is crucial, involving direct contact, visits and communication with the tourist services involved in the programme, since they know the circumstances of the place in question better than anyone. Regarding the latter (demand-side) it is not only important to understand the profile of senior tourists before the trip or experience takes place (their characteristics, motivations and sources of information); but also the after-experience: how they feel about it and what their opinion and perceptions are.

An understanding of the all stages of the experience should be tackled, since this approach is strongly related to senior tourism behaviours. It is believed that this type of marketing-integrated approach offers excellent opportunities for the tourism industry to design custom-tailored products and services.

3. Methodology

3.1 Senior tourism marketing projects: some examples

Comprehensively, elderly consumers have different requirements compared with other market segments, and “these differences are expected to have marketing implications since older consumers may differ in their product needs, media habits and even in the way they process information” (Nella & Christou, 2016, p. 3). In order to better understand these specific requirements and motivations, it is crucial to develop a framework based on the literature and try to identify some senior tourism projects in Portugal and Europe in general as good practices in the marketing of this form of tourism.There are several senior tourism programmes within social tourism, which means that for tourism to become accessible for all, the opportunity for underprivileged groups to travel must be opened, boosting local economies and employment opportunities at the same time. One well-known social tourism programme is CALYPSO, a European programme that was created in 2009. This programme targets four categories: seniors; youths aged 18-30; people with disabilities; and families on low incomes. Its budget was increased in 2011 from €1 million to €1.5 million in recognition of its potential to reach disadvantaged groups, also spreading the tourism season more evenly across the year. By encouraging low-season, cross-border tourism, CALYPSO increases the chances for travel for those who find it difficult to holiday abroad (see http://www.ecalypso.eu/steep/public/index.jsf). Still in Europe, it is important to consider that senior tourism is associated with accessible and inclusive tourism. It is important to highlight the ESCAPE project (see https://www.accessibletourism.org/?i=enat.en.enat_projects_and_good_practices.1883), a project that brings together eight partners who have joined forces with a view to working on enhancing the existing tourist infrastructure and staff in the low season, thus facilitating transnational exchanges off-season by concentrating on the senior citizen market. This project includes a total of five ESCAPE tourism packages targeting senior citizens during the low-season period.

Another European project is called SENIOR Train: European Senior Tourism Project. This project is about fostering senior travel throughout Europe by train, offering innovative dynamic tourism packages that include all transportation-related services as well as necessary information, accommodation and value-added services. This project aims to facilitate pan-European mobility for seniors by rail, developing innovative tourism packages that are tailor-made for the target group and its needs (https://www.accessibletourism.org/?i=enat.en.enat_projects_and_good_practices.1886).

The Seniors Go Rural - SenGoR - Senior Tourism Project is also worthy of mention; it defines a generic operative model to generate and market products based on individual arrangements that facilitate transnational tourism flows of seniors in the low season to rural micro-business and SMEs and their destinations. (see https://www.accessibletourism.org/?i=enat.en.enat_projects_and_good_practices.1885).

In Spain there is also an interesting project named Europe Senior Tourism, a programme of all-in holiday packages, which give an opportunity to discover Spain from October to May, including flights, transfers, three- or four-star hotel, half-board, spas, a destination experience and travel insurance (see http://www.europeseniortourism.eu/en/index.html). It consists of a travel programme sponsored by the Spanish government designed for European seniors aged over 55, who are resident in a European Union country (except Spain) and who wish to enjoy active holidays while sharing experiences.

In Portugal, the organization that provides the access to travel for elderly people is INATEL. The programme Inatel 55+ is an offer that is aimed at the senior market, aged 55 or over, and intends to offer all people who meet the requirements (age and expected income levels) the opportunity to travel, enabling them to occupy their free time through contact with the country's cultural, gastronomic and natural heritage.

The programme includes accommodation and diversified leisure activities, particularly cultural, innovative training in the fields of citizenship, healthy eating and health prevention, promoting social inclusion of citizens with a view to providing socio-cultural integration for the programme’s beneficiaries (see https://www.inatel.pt/getmedia/75ef1090-15ea-45d3-b12b-c98372cc9a52/PDF_Informativo-3.aspx). It lasts 6 days and 5 nights, on a full-board basis, including transportation, entertainment at the hotel and various activities of a recreational and cultural nature, as well as sightseeing tours accompanied by a tour animator.

One of the recent projects in Portugal is the Tu-Sénior 55+ - Senior Tourism and Well -Being in the Azores (see https://www.portugal2020.pt/content/projeto-nos-acores-vai-criar-produtos-turisticos-para-seniores). This project focuses on the design, structuring and development of a promotional product of sequenced actions and initiatives that integrate cultural and environmental activities in an coordinated framework and sets up an occupational itinerary that meets the health and well-being needs of people aged over 55.

These are just some examples that attempt to highlight the marketing perspective of targeting the senior market. Despite the differences among them, there are points in common such as: more in-depth market research about the main motivations; specificities and requirements of this type of market; the process of conceiving tourism experiences particularly directed at the senior market; and the message that these programmes do not have territorial boundaries, with a truly partnership-based model.

3.2 The “VOLTO JÁ” project: an overview as a case study

This article is based on a senior exchange project - VOLTO JÁ (“I’ll be right back”) - with the mission of providing tourism experiences to institutionalized elderly people in social economic organizations. The general aim is the operationalization of a social senior’ exchange programme between social economy organizations (SEO) that promote cultural, touristic and artistic experiences. This study is based on a single case study as one of the most frequently used qualitative research methodologies. Nevertheless, as argued by Yin (2002), one of the foundational methodologists in this field, it still is not yet sufficiently legitimized as a social science research strategy since it does not have a clear-cut protocol (Yin, 2002). This study is more in line with Merrian’s epistemological stance on the case study, since according to her, “the key philosophical assumption upon which all types of qualitative research are based is the view that reality is constructed by individuals interacting with their social worlds” (Merriam, 1998, p. 6). In this sense, the case-study approach that guides the OEC model has as its primary interest understanding the meaning or knowledge constructed by people in a more integrated approach, in this case by institutions and seniors. In this sense, the project VOLTO JÁ has its foundation in the current scenario of population ageing. In our country, ageing rates are gaining momentum and it is important and even urgent to invest in initiatives that can fill some gaps, is not only an ageing country, but a scenario in which the elderly live in isolation and in unprotected economic as well as social contexts.

Tourism is a sector that has in fact evolved and expanded its intervention to the most diverse areas and to the most diverse target audience, regardless of their condition. In this sense, the VOLTO JÁ project is innovative and is based on the sharing of resources between SEO in order to enhance a value-added proposal. It is a programme that has a direct and immediate impact on the lives of the participants in the mobility through social inclusion and equal access to opportunities, and is a project structured by a multidisciplinary team from two higher education institutions (Polytechnic Institute of Santarém and Polytechnic Institute of Beja) and which also has Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Santarém as a partner institution.

The VOLTO JÁ project devises a set of actions with direct impact on seniors’ mobility and social exclusion. The elderly taking part in VOLTO JÁ will experience a recreational context, some of them for the first time (Oliveira et al., 2017).The intention is to develop and implement a business model with a special focus on a senior institutionalized segment (in homes or day centres), based on a network of social economy institutions that guarantee exchange services in the Alentejo region. Through a mobility service between participating institutions, the model offers seniors the possibility of experiencing experiences similar to those of leisure and vacations and, at the same time, enjoying cultural moments and sharing experiences at low cost (Oliveira et al., 2017).

Implementation involves the design of a platform based on information and communications technologies (ICT) to manage: the registration of participating institutions (willing to promote exchanges for institutionalized senior individuals); the registration of seniors’ exchange services (demand and supply); and institutions' access to social tourism packages (accommodation, leisure experiences and tourist experiences, among others) (Amaral et al., 2019; Rodrigues, Amaral & Diniz, 2020).

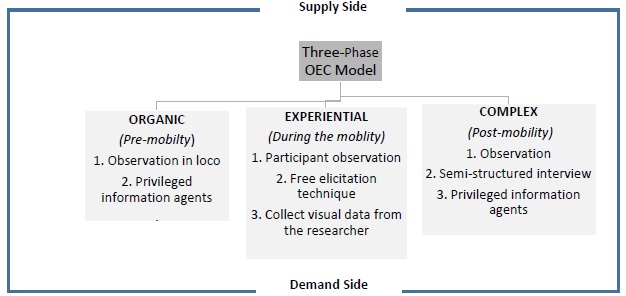

3.3 Evaluating tourism senior experiences: OEC model proposal

The whole process of designing and evaluating tourism experiences in senior mobility is framed by the OEC model (Organic, Experiential and Complex model), established on the basis of a set of data collection instruments which were carefully and appropriately chosen, according to the goals of each stage of the process. The OEC model is intended to be a framework for developing marketing strategies related to this segment, since it covers all stages of a senior experience (before, during and after). The rationale of the model is influenced by the destination image formation process (induced, organic and complex) as proposed by Rodrigues, Correia & Kozak’s work (2012) in their theoretical categories of the destination image construct. The organic image is the result of a reader's assimilation of material from newspapers, periodicals, and books previous to the experience of visiting a place (Gunn, 1972; Hankinson, 2004). This leads to the importance of a pre-stage that takes place before a visit. The experiential image that is formed when the tourist is experiencing a destination (Vaughan & Edwards, 1999); and the complex image obtained upon visiting selected destinations resulting from actual contact with the area (Fakeye & Crompton, 1991). In sum, the OEC model is conceived as a catch-all model that aims to cover all the stages of a senior tourism experience.

Framed by this model, the study developed was based on the following research questions extracted from the literature review and is grounded on three main topics: senior tourism experience; experience dimensions and tourist satisfaction.

RQ1: How was the experience considered by the elderly participants who participated in the exchange programme?

RQ2: What were the main dimensions of the tourist experience in this exchange programme?

RQ3: What was the overall assessment of satisfaction with the experience by the elderly participants?

Because of that, the data provided by this model is crucial for the design of appealing tourism products and the corresponding communication, pricing and distribution strategies (i.e. marketing strategies).

The OEC model is divided into three stages (Rodrigues, Amaral & Diniz, 2020):

1 st stage/Organic/Pre-mobility: named organic since the data collection is undertaken before the mobility takes place in order to assess the profile, motivations and perceptions of seniors. The data collection techniques are observation in loco by the researcher (inspection visit) in order to evaluate the tourism package components to be included in the mobility programme (quality and type of accommodation; location and accessibility of museums, churches and other components for seniors) and privileged information agents through contacts and conversations with the staff from the social economy institutions that participate in the mobilities, since they know the circumstances of the territory in question better than anyone;

2 nd stage/Experiential/During-mobility: the second stage is named experiential, where the data is collected during the precise period of the mobility programme. The data collection techniques are participant-observation where the primary data is extracted through field notes, based on direct observations, which become the core data and the basis of the analysis and report. Usually, observation is also combined with informal, conversational interviews and personal experience and a free elicitation technique; in addition, to complement the data collection, visual data was also used, through photos taken by the researcher during the mobility;

3 rd stage/Complex/Post-mobility: in this stage, data is collected after the mobility programme takes place in order to give some time for the seniors to reflect upon the experience. The data collection techniques are observation in loco through a visit after the mobility to interview the seniors who participated in the experience and with the privileged information agents, by conducting also a semi-structured interview. Crucial information is obtained here that addresses three dimensions: (a) evaluating the mobility experience by the seniors that are part of the mobility programme; (b) assessing the senior experience through models of dimensions of the experience; (c) assessing the levels of satisfaction with the tourism experience (mobility programme).

Triangulation of methods and data is the goal in order to enrich the analysis by crossing multiple perspectives, insights and techniques. The OEC model follows all phases of the process of conceiving and evaluating tourist experiences in senior mobility in order to provide an evolutionary, holistic and dynamic view of the whole process to inject feedback into the system. They are all made up of distinct but complementary data collection tools.

The OEC model (see Figure 2) is grounded on the assumption that supply should be adapted to demand and each mobility programme has different specificities and contexts. All stages are fundamental and complement each other; each of them contributes so that the mobility programme is considered as offering unique and authentic experiences, fostering above all the essence and motivation of all stakeholders involved.

Figure 2 Model for Design and Evaluation of Tourism Experiences in Senior Mobility (OEC Model-Organic, Experiential, Complex Model). Source: Rodrigues, Amaral & Diniz (2020).

Based on the goals of the present study, only the 1st stage/Organic/Pre-mobility and 3rd stage/Complex/Post-mobility will be considered for the methodology and results analysis. Further research will focus on the 2nd stage/Experiential/Post-mobility.

3.4 Data collection, procedure, participants and analysis strategy

1 st stage (Organic)

This important stage took place during pre-mobility with the first contacts being made with the receiving institution. This is where the first approach took place between the project team (responsible for conceiving the tourism packages) and the technical assistance team for the participation of the institution in the exchange. In this stage, the team carried out several actions, which bring together core elements for the process of conceiving the tourism packages:

Definition of the SEO partners (project presentation and all its assumptions);

Participant selection (profile identification, motivations and interests, mobility limitations, expectations, pre-mobility questionnaire application);

Tour package planning (listening to the SEO in order to identify and select the most interesting and most suitable places to visit for this market (elaboration of pre-programme);

Tourism package design (identifying and establishing formal protocols with potential partners which guarantee all the necessary elements for the implementation of the first planned programme (the final programme is already assured at this point);

Inspection visit (on-site evaluation regarding the places to visit and ensuring that all components are guaranteed, i.e. accommodation, meals, accessibility, transport, tickets and comfort, among others).

In order to accomplish these actions, several contacts with institutions potentially interested in doing exchange programmes were made, based on meetings, informal interviews and focus groups. To accomplish the inspection visit, an in loco, non-participant observation technique was used.

3 rd stage/Complex

This important stage took place after mobility took place (post-mobility). Considering the OEC model, the team used several techniques to obtain a clear level of responses based on:

24 semi-structured interviews with elderly people that participated in the exchange programmes and observation (each interview took about 15 minutes on average; age of the participants between 65- 85)

Complementary information with privileged information agents after the exchange programme.

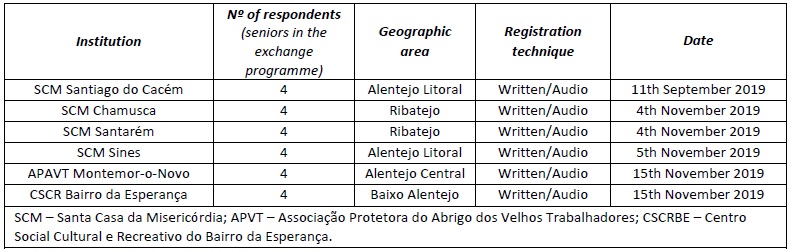

A complete list with detailed information of the respondents can be seen in Table 2.

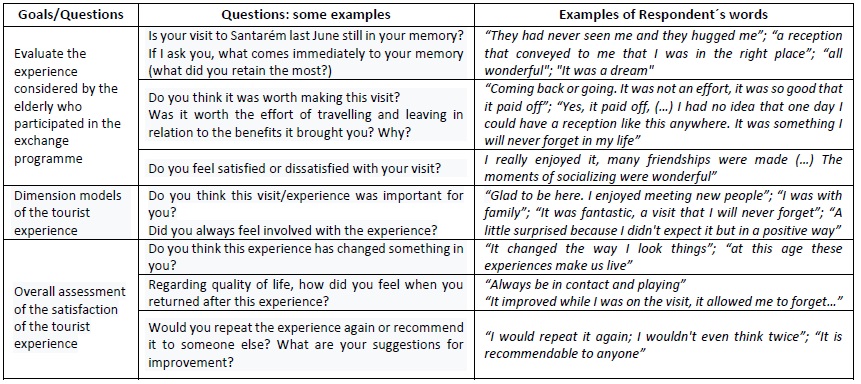

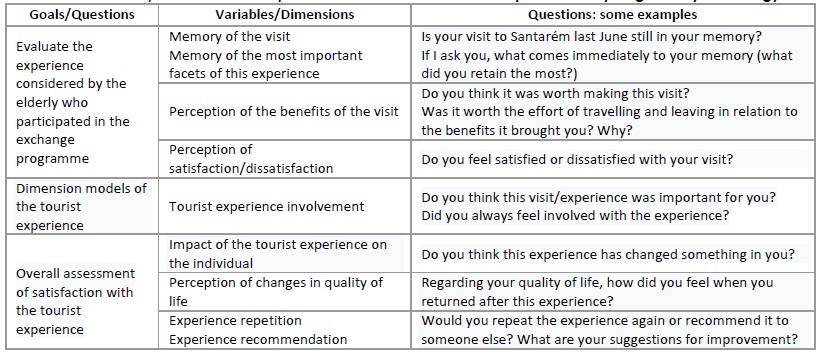

Interviews were based on semi-open-ended questions related to the post-experience phase in order to collect information. Due to the characteristics of the respondents, more open and free interviews were the most suitable. As stated by Turner (2010:756) “this open-endedness allows the participants to contribute as much detailed information as they desire and it also allows the researcher to ask probing questions as a means of follow-up”. For the interview structure, the team had to consider the characteristics of institutionalized elderly people and mainly their capacities mostly related to memory (or lack of it) and motivation to answer. In fact, some limitations arose from the period between pre- and post-mobility, since the elderly have memory limitations and registration in some cases had to be delayed because the exchange was only concluded several months later. Authorization for data collection was reinforced through detailed information shared with the respondents on the objectives of the study; the justification and the framework were presented to the respondents, as well as the guarantee of confidentiality in the responses. The interviews took place during the period of the exchange programmes (between September and November 2019). The final structure of the interviews is presented in Table 3:

Table 3 Goals, dimensions and questions of the interviews in the post-mobility stage: analysis strategy

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Considering a qualitative perspective methodology, the interviews were analysed using a content analysis procedure. According to Bardin (2009), this technique is characterized by the search for explanation and understanding, allowing inferences to be made, which, in a systematic and objective way, identify singular and implicit characteristics of the discourse. The content analysis itself is done through a coding table of the interviews and includes (Bardin, 2009): i) category (here the main themes of the interview are added); ii) subcategory (most important subthemes within a given major topic of the interview); iii) registration unit (text fragments that are taken as indicative of a characteristic - category and subcategory); and iv) context unit (fragments of the text that encompass the registration unit, contextualizing the registration unit in the course of the interview).

Regarding the analysis strategy, this study is essentially explorative and a more “deductive procedure” was undertaken since a prior formulated theoretical schema was used (Mayring, 2000), based on two main topics of: (a) senior travel experience evaluation and (b) tourist satisfaction. In fact, the goal was to depict sensations, emotions, perceptions and opinions about the experience itself and their final satisfaction in an open and free way. For that reason, in terms of coding procedure, a direct approach was adopted where “the researcher uses existing theory or prior research to develop the initial coding scheme prior to beginning to analyse the data” (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005, p. 1286). The qualitative step of these categorizations and analysis consists of a methodological controlled assignment of the category to a passage of text. A descriptive method that “summarizes in a word or short phrase - most often as a noun - the basic topic of a passage …” (Saldaña, 2009, p. 70) was adopted.

4. Results

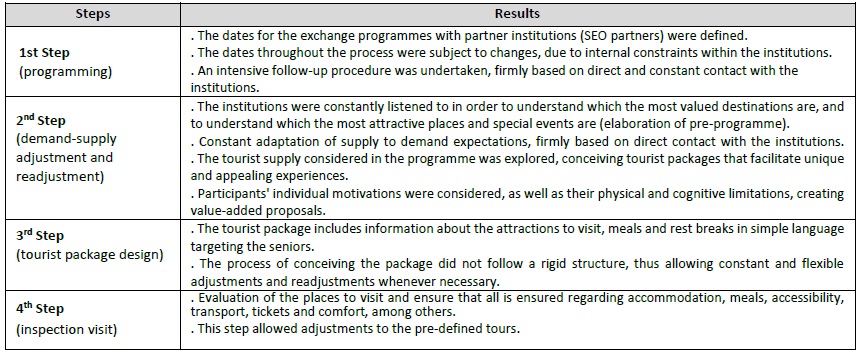

The results are presented in this section under the framework of the OEC model that should be taken into consideration for the design and evaluation of senior tourism experiences. Therefore, this study assumed that the results generated by the OEC model might contribute to the development of marketing strategies, in this case for the institutionalized seniors from social economy organizations (SEO), the partners of the VOLTO JÁ project. These results, as previously mentioned, describe the outcomes extracted from the procedures that took place during the two stages of the OEC model (organic and post-mobility). A total of six senior exchanges were carried out, with a total of twelve travel exchanges, since these were not carried out simultaneously, allowing participants to join two exchange programmes.

1 st stage (Organic)

The organic phase is composed of steps that occur at different moments in the process (see Table 4). In the first approach, Step 1 - programming - where indicators are collected in relation to the temporal moments in which the exchange took place, the most appropriate dates were defined according to the institution's annual schedule of activities. In Step 2, demand-supply adjustment and readjustment to the expectations of the participants were considered. These indications are provided by privileged information agents internal to the institution; the premise of the project team was to value the participant and provide him with unique experiences which provide well-being and happiness.

In Step 3 - tourist package design - all the objectives of the previous actions are considered. Here the expectations of demand-side (seniors) take shape through the process of conceiving a tourist package tailored to each group of participants in each. These were subject to readjustment for reasons outside the team's domain, for example, weather issues and physical limitations of the participants.

In Step 4 - inspection visit - all the assumptions defined and presented in the tour package were monitored. Here, the project team visited the place, checking if all facilities and services were ensured and all questions related to safety and well-being of the seniors were catered for. These steps, although independent, are interconnected and if one of them is not carried out it will compromise all the requirements of the process. This step is decisive for the project, since it is here that the first contact is established with the institution and with the seniors when planning all the activities.

Table 4 Results from the organic stage of the OEC model: the process of conceiving senior tourism packages for the VOLTO JÁ project

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

3 rd stage/Complex

Via analysis of the 24 interviews carried out face-to-face at the institution of origin of the elderly and after the mobility was carried out, the first aim was to perceive their perceptions regarding the experience of the visit they had undertaken. It is important to highlight that this is an exchange programme, which means that the visit is evaluated both from the perspective of the destination they are visiting and from the perspective of the programme designed to receive visitors from the other institution (see Table 5).

In most of the responses, it appears that what was best recorded in their memory were the relationships of friendship that emerged during the programmes; the social moments provided; the affection generated; the good reception of the host community; the good condition of the receiving facilities; and the place visited and the tours associated with the visit.

Most of the interviewees considered that carrying out these visits was positive, namely for the benefits they derive from it in terms of knowledge of the destination and its attractions and the reception of the community that received them, leaving them with a great desire to do more exchange programmes. All respondents showed great satisfaction with the exchange programme, stating some reasons for this opinion, namely: i) accommodation (cleanliness and quality conditions); ii) transportation; iii) programme of the tour taken; iv) use of merchandising and its symbolic value (caps and T-shirts created with the logo of the VOLTO JÁ project); v) social moments provided; and vi) the friendliness of the entire team. These results are in line with Otoo & Kim (2018) when they mention that in terms of socio-personal perspective, travel contributes to the improvement of quality of life and promotes active ageing.

Another category of interview analysis was to understand the dimensions of the senior tourists’ experience. From analysis of the interviews, we concluded that the seniors value this experience that was provided highly, essentially because it was an opportunity for them to get to know a new place, to travel or to roam. In addition, they consider that they had no doubts about their willingness to participate. The feeling generated is that the experience was important for them, particularly because of the family environment created and also due to the people and colleagues from peer institutions that they had the opportunity to meet. Once again, the idea is reinforced here that the experience is also perceived as being linked to affections and the establishment of friendships, almost in a “family environment”. Some of the responses reinforce this idea: i) “I saw that I was with family”; ii) “it was very important”; iii) “it was fantastic, a visit that I will never forget”.

Concerning the purpose of these interviews to give an overall assessment of the satisfaction with the tourist experience, the results show that seniors mainly highlight aspects related to how the experience changed them as a person, by giving good thoughts about the way they see life; knowledge acquired from the destination and its resources; the opportunity to grow by seeing other situations; feelings of joy and happiness and tranquillity; and the opportunity to meet new people. Most interviewees would like to repeat the experience by doing more exchange programmes. Some of the responses reinforce this idea: i) “it changed the way I started to look at things”; or ii) “At this age, these experiences make us live”. The responses also reinforce the perceived relationship between the exchange, the lived experience and the improvement of their quality of life, with the same answers once again providing the idea that feelings of happiness and joy and a better mood are generated; a perceived increase in strength; a willingness to learn new things and interact with people and a desire for exchanges to last longer. These results are aligned with the literature review (Sie et al., 2016) in that senior travel experiences are related to refreshment, socialization, bonding time, self-fulfilment and nostalgia, among others.

Reinforcing the observation that elderly people were satisfied with exchange programmes and this touristic experience, most of those interviewed said that they would recommend these activities and if there was another opportunity, they would do it again. As one of the interviewees said: "I would repeat it again; I wouldn't even think twice”.

5. Conclusion

An important element is the affective bonds that participants create with each other. There is a constant refusal on their part to be “mobility colleagues”, as in their understanding they are not colleagues but friends, friends with different stories, lives and opportunities, but all in all, they are nothing more than vivid memories of what they once were. This allows for a very genuine environment where these people are willing to give anything, and where their only interest is a smile from their new friend, or an outstretched hand to support them while on the move. In fact, they know each other's limitations and aspirations better than anyone else; the encounters are exciting, but goodbyes are marked by tears and promises of a reunion. This is the essence of the VOLTO JÁ project.

Throughout this process, very revealing and curious data were collected, from the existence of people who had never travelled to people who had never seen the sea. It is important to note that both economic and social or even cultural indicators are present in the basis of these revelations. Many of them had an economically unprotected life which only allowed them to work to guarantee their family's livelihood and many of these cases are reflected in those who were not given the opportunity to study or have contact with other situations other than the rural environment where they lived. On the other hand, and curiously more present in the female gender, social and cultural indicators are associated; these were very “closed” means, where the education of women wsa mostly carried out through the home and the family, with no great opportunity to learn about other situations or have other experiences.

These are some examples of information that made it possible to plan tourist packages and given all these limitations it makes sense to provide these users with exclusive experiences that really mark their lives. This also allowed the existence of very different tourist packages that crossed past aspirations with the present dynamics of the tourist supply.

It is of utmost importance to consider the promotion of well-being by engaging active ageing. For all these reasons, it is crucial to create strategies that respond to this new paradigm that is imposed on today's societies, characterized by people who above all seek exclusive experiences, favouring activities that allow them to get in touch with local communities and that portray past experiences. Moreover, investment in the re-growth of this market segment is much required. It is not sufficient to present innovative tourism practices, but it must be ensured that they are, in fact, meeting their needs. It is also important to take the cultural and social aspects of this population segment into account, as they often resist new tourism practices. Undoubtedly, it is a process that requires time and insight, as senior tourists are very faithful to their convictions, not only looking for excellence in a destination, but also moments of relaxation and conviviality. In this age group it is essential that the tourist feels accompanied, safe and above all valued as a person (Patuelli & Nijkamp, 2016). These are requirements that needed to be taken into consideration for managerial and marketing decisions.

The results provide valuable insights into how to define the most suitable marketing strategies for senior tourism, particularly for institutionalized seniors, since an evaluation of all their experience was taken into consideration. Further research will continue to explore marketing strategies based on these exploratory studies.