Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.15 no.3 Faro set. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2019.150304

MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Organizational resilience: proposition for an integrated model and research agenda

Resiliência organizacional: proposição de um modelo integrado e agenda de pesquisa

Cristina Chaves Goldschmidt1, Kely César Martins de Paiva2, Hélio Arthur Reis Irigaray3

1Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas (EBAPE), Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV), cristinacgoldschmidt@gmail.com

2Faculdade de Ciências Econômicas (FACE), Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), kelypaiva@face.ufmg.br

3Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas (EBAPE), Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV), helio.irigaray@fgv.br

ABSTRACT

This theoretical essay is aimed at shedding light on and synthesizing the concepts of resilience in relation to employees and organizations and proposing an integrated analysis model that gives rise to a research agenda embracing methodological aspects and thematic connections, which might contribute to a debate on the construct that involves differentiated levels of analysis. Accordingly, a historic review of the construct’s discussion and its specificities will be presented, including the following organizational resilience concepts: the procedural, dynamic, and ecosystemic capacity activated by people (individual resilience) and processes (systemic resilience) in the face of adversity, the generation of a response that allows the recovery of balance, and the performance of healthy adaptation through the activation of elements, in the subjective or internal and objective or external plans, which might be reinforced or renewed during the process, thus ensuring the sustainability of the resilient result and/or the expansion of resilience capacity.

Keywords: Resilience, organizational resilience, individual resilience, systemic resilience.

RESUMO

Este ensaio teórico visa esclarecer e sintetizar os conceitos de resiliência em relação a empregados e organizações, bem como propor um modelo de análise integrado que fundamente uma agenda de pesquisa e contemple aspectos metodológicos e conexões temáticas, podendo contribuir para um debate sobre o construto que envolva níveis diferenciados de análise. Dessa forma, será apresentada uma revisão histórica da discussão do construto e suas especificidades, incluindo os seguintes conceitos de resiliência organizacional: capacidade processual, dinâmica e ecossistêmica ativada por pessoas (resiliência individual) e processos (resiliência sistêmica) diante de adversidades, possibilitando a geração de uma resposta que permita a recuperação do equilíbrio e a realização de uma adaptação saudável por meio da ativação de elementos, nos planos subjetivos ou internos e objetivos ou externos, que poderão ser reforçados ou renovados durante o processo, garantindo a sustentabilidade do resultado resiliente e/ou a expansão da capacidade de resiliência.

Palavras-chave: Resiliência, resiliência organizacional, resiliência individual, resiliência sistêmica.

1. Introduction

Initially imported from engineering material and with meanings that overlap with other fields of knowledge, resilience is a construct that has been used systematically in administration (Burnard & Bhamra, 2011; Coutu, 2002; Denhardt & Denhardt, 2010; Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2003; Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003). In this field, resilience appears as the output of the interaction between the subject or the system and the environment in which it is situated, delineating two perspectives: people’s resilience in the organizational environment and organizations’ resilience.

Psychology exert a strong influence on the comprehension of resilience: Lengnick-Hall and Beck (2003) affirmed that, although academic works in the administration area have involved discussions on resilience, such as those by Collins and Porras (1994) and Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003), the major part of the production related to the construct belongs to the field of psychology. Yunes and Szymanski (2001) highlighted that the definition of resilience is not as clear and precise in this field as it is in physics or engineering. According to the authors, “It is not possible to compare ‘apples and oranges’, i.e. to compare the resilience of materials with resilience as long as it represents a psychological process” (Yunes & Szymanski, 2001, pp. 1-2).

Besides, the word resilience has been used more frequently in popular management articles and publication interviews, such as in the magazines HSM Management, Harvard Business Review, Você S.A., and Exame (Carneiro, 2015). On the other hand, this topic has recently attracted the attention of researchers in the fields of management and organizational studies, at the levels of both individual and organizational analysis (Correio, Correio,& Correio, 2018; Kahn et al., 2018; Kamlot, 2017; Raasch, Silveira-Martins, & Gomes, 2017; Shin, Taylor, & Seo, 2012; Sonaglio, 2018; Stuart & Moore, 2017; Vasconcelos, Cyrino, Carvalho, & D’Oliveira, 2017; Vasconcelos & Pesqueux, 2017; Vieira & Oliveira, 2017), but without putting forward a proposition for multi-level analysis.

Even though resilience has attracted the attention of the market and scholars for years, a common definition remains evasive. Whereas most authors have agreed that it means the capacity to grow and advance in the face of adversity, considerable ambiguity still exists around the subjacent processes that compose resilience. In this sense, some authors have defended the necessity of greater clarity in the use of such definitions (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker 2000), which has made the understanding of the construct of resilience, its evolution, and its significant aspects in the labour world even more evident as a condition for the elaboration of methodological, epistemological, and praxeological propositions, amplifying, in a pragmatic form, the possibilities of access by individuals and organizations to a repertoire of productive responses to the adversity experienced in the contemporary environment.

The proposal of the present theoretical essay is to shed light on and synthesize such conceptual questions considering the labour world, that is, labourers and organizations, and to propose an integrated analysis model that, on the other hand, gives rise to a research agenda that embraces the methodological aspects and thematic connections. Accordingly, a historic review of the construct’s discussion as well as its specificities in the labour world will be presented, including differentiated analysis levels and the proposition of an integrated model and a research agenda.

The history of the word resilience can be found in several fields of knowledge; this review starts by focusing on physics and engineering and then enters the human sciences, specifically psychology, in view of the depth of its contributions to the present essay.

2. Resilience in the administration field: what the literature has reported

In engineering and physics, the conception of the term resilience arose in experiments during which metals were submitted to different pressures (temperature, strength, etc.) to determine the degree of elasticity that they can support without being destroyed. As a concept, the study of resilience dates back to 1807 and continues until the present day (Timoshenko, 1976). In the human science field, resilience presents polysemy, being conceived as a path, a continuum, a system, a trace, a process, a cycle, or even a qualitative category (Rutter, 1985; Tusaie & Dyer, 2004). According to Zautra, Hall, and Murray (2010), resilience can also be analysed on different levels: basic dimensions, such as the biological, cognitive, emotional, behavioural, and human life phase perspectives, the social and organizational dimension, or the community dimension, and under the lens of ethnic aspects and different cultural dimensions.

In the administration field, two analysis levels for resilience are observed: the resilience of people in the organizational environment and the resilience of organizations. The study of resilience in this field allows the exploration of the factors that have a direct impact on the performance of organizations in their (macro) environment and of persons in their (micro and meso) professional environments, influencing the organizations’ shortand long-term results.

As the literature on organizational resilience is still underdeveloped, Denhardt and Denhardt (2010) recommended considering the following:

1. The perspective that the authors follow, that is, the psychological (Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2003) or system perspective (Horne, 1997), and whether the approach focuses on the timely reaction to circumstances with a very large reach (Lengnick-Hall, Beck,& Lengnick-Hall, 2011) or on the long-term adaptation capacity (Hamel & Valikangas, 2003), which Denhardt and Denhardt called everyday resilience (Denhardt & Denhardt, 2010, p. 336); and

2. Whether the author focuses on survival, innovation, or qualification construction (Hamel & Valikangas, 2003; Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2003; Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003).

The presence of adversity in the organizational environment demands response actions from individuals, that is, dealing with adversity in a positive way, dealing internally/subjectively and externally/objectively with the stress caused by the adversity, noticing and evaluating the risk factors presented by the adversity, determining how to adapt better to an eventual new context presented by the adversity, and learning from the adverse experience.

In the organizational context, human resilience is defined as the capacity to rebound or bounce back from adversity, conflicts, and failures as well as representing progress and increased responsibility. Denhardt and Denhardt (2010) asserted that “Resilience involves the ability to adapt creatively and constructively to change, and change is one constant in organizational life today” (Denhardt &Denhardt, 2010, p. 333). These authors defined resilience as the ability to bounce back from adversity (which varies from disasters to power disputes, passing through turnover crises) so that the organization becomes more flexible and prepared to adapt itself to future adversity.

Thereby, resilience on the individual level is a quality and a capacity that people should look for as long as they are workers, leaders, and managers in organizations, and they should try to develop it continuously (not only during disasters or external and internal crises), implying that the understanding of a resilient individual might supply a basis on which to define resilient organizations, as the interactions between individuals, as well as their isolated actions, support the collective resilience capacity of an organization (Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2003).

It is important to clarify that a difference between individual resilience and company resilience can be observed in the same way as it has already been observed between individual and organizational learning. After all, as Rodrigues, Child, and Luz (2004) pointed out, individual learning might be “contested” from several angles within organizations - politically, ideologically, pragmatically, and so on. Paiva (2013) also observed this division between professional competences and organizational competences. In synthesis, the organizational analysis level comprises more than the sum of the individual parts’ contributions; thus, organizational resilience is not merely the joining of individuals’ resilience but actually comprises individual contributions aggregated by a system or process set that allows and promotes daily implementation. To sustain this argument, two pillars need to be developed further: human resilience and organizational resilience.

2.1 Individual resilience

Working towards a conception beyond the risk-protection dyad, Luthar et al. (2000), Masten (2001), and Waller (2001) approached the human resilience phenomenon as a dynamic, multidimensional, or ecosystemic process. In this sense, it should be emphasized that the conceptions of resilience have changed over the years from the perspective of an absolute and global attribute to the perspective of a relative and circumstantial capacity. Thus, two critical conditions are implicit in the notion of resilience: exposure to adversity (threat/risk or a positive event) and the achievement of positive adaptation. By definition, resilience is positioned in an interdependent way in relation to adversity; that is, to demonstrate resilience, the adversity or challenge should be met in the first place (Charney, 2004; Masten & Wright, 2010).

According to Zautra et al. (2010), there are two dominant themes that are central to the concept of resilience: (1) as an answer to stressful events or adversity, resilience focuses on the recovery, which is the ability to recover from stress and the capacity to recover the balance (physical and psychical) quickly, returning to the balanced, healthy, or productive state (Masten, 2001; Rutter, 1987); and (2) resilience as the result of successful adaptation to adversity implies the continuity of the recovery trajectory, generating the sustainability of the healthy balance, which allows the improvement of the functional capacities to deal with future stress and/or adversity and to continue to move forward in the face of adversity, as in a virtuous cycle.

Denhardt and Denhardt (2010) asserted that individuals do not survive adversity by merely returning to their previous state. In fact, the key to psychological resilience is the capacity to adapt, learn, change, and become more resilient. Thus, resilience extends much farther than resisting stress, recovering, “bouncing back”, or moving within the bouncing back: the adjustment question or coping is central and will be deepened in the following section.

It should also be mentioned that individual, social, cultural, and environmental factors influence the global capacity of an individual to recover himor herself. According to Masten and Wright (2010), although the study of human resilience focuses specifically on the understanding of individual differences in view of adverse experiences, resilience should not be conceptualized as a trait or static characteristic of an individual, as it emerges from several processes and interactions that reach beyond the human body and include interpersonal relationships and the social context to achieve positive adaptation. Still within the approach to resilience as a process that results in positive adaptation, Carver (1998) made a clear distinction between resilience as a return to the previous level of functioning, that is, recovery or bouncing back, and thriving as a movement towards a superior level of functioning after a stressful event.

Within the resilience conceptions that are representative of the thriving conception, which include those of Carver (1998), Grotberg (2006), and Waller (2001), among others, the term positive adaptation integrates a large part of the definitions of the construct. The definitions within the thriving sense clearly describe a process in which adversity is overcome and the strengthening character of such an experience. Thus, with regard to positive adaptation, the dichotomy (or continuity) deserves deepening, that is, conformity versus thriving. In the sense of thriving, resilience is a process in which the recovery of homeostasis (balance) exists, and this recovery might lead to an individual overcoming the adversity faced, whenever he or she learns from the adverse experience and strengthens himor herself.

Luthar et al. (2000, p.10) indicated that “positive adaptation (…) is considered in a demonstration of manifested behavior on social competence or success at meeting any particular tasks at a specific life stage”; that is, positive adaptation is generally defined in terms of competence to manifest a social adaptation or success in tasks that involve development from previous adverse experiences (Luthar et al., 2000). Positive adaptation might be identified as the moment in which an individual succeeds in meeting social expectations, overcoming adversity, and developing himor herself from it or when no signs of inadaptability exist in the individual (Infante, 2005).

However, Infante (2005) drew attention to questions that should be raised when working with a definition of resilience that bears such an adaptation idea (manifestation of a pursuant social behaviour), due to the ideological character that is connected to the adaptation idea associated with normal development and to some society expectations. According to the author, the following questions should be asked: What defines what is normal? Who defines it? What would the evaluation parameters be for normal development?

For Melillo (2004), associating resilience with positive adaptation seems to neglect the consideration that an individual is an active agent who acts on society and might transform it. According to this author, if resilience is thought of in terms of positive adaptation in the context of totalitarian regimes, which continue to prevail in South America, it might mean only subjugate survival.

Galende (2004), agreeing with Melillo’s (2004) approach, pointed out that adaptation, as a sign of submission to a certain reality, cannot be considered resilience. In complement to the thought of Galende (2004), according to Tavares (2001), in the emerging society, resilience should be constructed in the sense of making persons stronger and better equipped to intervene socially and not making them more insensible, passive, and resigned.

Yunes and Szymanski (2001, p. 35) referred to “performative resilience”, which is a concept that was constructed by Martineau (1999) and defined as the “conformity to social standards, academic success and empathy for others, but only manifested with the objective to please or to deceive” (Yunes & Szymanski, 2001, p. 35). Sometimes conformity manifestations occur in the exchange of a very high “price” for the mental health of an individual, who might appear to be very well in relation to something that he or she has to face or has already faced in life but for whom actually the demonstration of overcoming is merely apparent.

2.1.1 Coping, confrontation, or adjustment

From the dynamic process perspective, in which the result is adaptation, adjustment or coping is a concept that is interrelated with resilience, which might give rise to conceptual ambiguity, but these terms are not synonymous (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The literature has presented different coping models, but coping has normally been defined as the “set of strategies utilized by persons to adapt to adverse or stressing situations” (Antoniazzi, Bandeira,&Dell’Aglio, 1998, p. 273).

The work of Lazarus and Folkman (1984) is a mandatory reference for those who intend to study coping. They presented a definition of coping that allows its understanding as intentional action, as this definition is based on the “constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the persons” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 141).

According to these authors, coping is a strategy and not a personality style. This means to say that the strategies might change from moment to moment during the stages of a stressful situation as well as during the development stages of an individual or even of his or her career or personal life or in the ambit of one organization. Coping involves cognitive answers in as much as it refers to specific thoughts, behavioural answers, and emotional answers that a person utilizes to administrate the internal and external demands of situations evaluated as stressful to protect himor herself from psychological damage.

Both coping and resilience are related processes, conditioned to adverse situations and/or stress. Coping is a mechanism that generates an immediate or a short-deadline result, such as the answer to a stressor, whereas resilience needs time to be developed (Skodol, 2010). Whereas coping focuses on the form, which is the strategy utilized to deal with the situation, independently from the achieved result, resilience concentrates on the result of the utilized strategy. A resilient result would be positive adaptation, in the sense of succeeding, of the individual before adversity (Skodol, 2010).

Richardson et al. (1990, p. 34) defined resilience as “the process of coping with disruptive, stressful, or challenging life events in a way that provides the individual with additional protective and coping skills than prior to the disruption that results from the event” and proposed an access process to resilience qualities as a conscious or unconscious choice function. In their model, resilience is presented in a simple and linear structure that portrays an individual or a group passing through biopsychospiritual homeostasis stages, interactions with events of life, rupture, readiness for integration, and the choice between resilient reintegration, returning to homeostasis, reintegration with loss, or dysfunctional reintegration.

Reintegration with loss (Richardson et al., 1990) reveals a very high “price” for the mental health of an individual, which is also dealt with by performative resilience (Martineau, 1999; Yunes & Szymanski, 2001), and its “social adjustment” sense that might produce “adapted” persons living in silent despair or even adapted as well as “non-adaptable” persons, as it implies conformity with certain conditions and values of the society but does not necessarily imply psychological health.

Regarding the dysfunctional reintegration state, Richardson et al. (1990) explained that it occurs when people resort to poor options (substance abuse, destructive behaviours, etc.) to deal with life’s demands. To cope with these, people can use a variety of therapies on the physical and psychological levels.

The model shows that individuals, in view of planned disruptions (marriage, pregnancy, a job change, etc.) or in reaction to life events, have the opportunity to choose, in a conscious or unconscious form, the results (outcomes) of the disruptions. In the model, the resilient reintegration stage refers to the reintegrative process (or coping process), which results in growth, greater knowledge, greater self-knowledge, and strengthening of resilience qualities. The resilient reintegration of Richardson et al. (1990) also implies thriving, as proposed by Carver (1998).

From the research analysis on resilience within the process perspective, Grotberg (2005) delineated eight new prerequisites that direct the present research, namely:

1. Resilience relates to development and human growth, including age and gender differences;

2. The strategies for the promotion of resilient behaviours are highly diversified;

3. There is no correlation between resilience and socioeconomic status;

4. Risk and protection factors are different resilience concepts;

5. It is possible to measure resilience;

6. Creativity in human development diminishes cultural differences;

7. Prevention and promotion are performance and implementation areas for the concept of resilience; and

8. Resilience is a process that includes resilience factors, resilient attitudes, and resilient results.

Considering such premises and resilience’s contextual character, in the present reflection, we call attention to the individual working peculiarities when exercising the managerial function, as, in a formal power position, the performance aims to attend to the different interests and results of the subordinate employees. From a manager, behaviours and results are expected that are often contradictory, a fact that characterizes the work as fragmented and ambiguous (Davel & Melo, 2005; Hill, 1993; Motta, 2007). Once it is understood that the manager’s task is to achieve effectiveness through his or her subordinates, the functional complexity rises, as the third-party dependence level is crucial to achieving the objectives, irrespectively of how the manager is perceived, that is, as the performance “mainspring” in the organization (technical perspective), as an element to mediate conflicts (political perspective), as a capital logic reproducer (critical perspective), or as the sum of all the previous perspectives (praxeological perspective) (Reed, 1997).

Thus, an employee, by exercising managerial functions, can facilitate or hamper the resilience of the third parties with whom he works, both informally in the daily work practices and formally through the processes that compose the organizational system. The compilation of these two elements, persons and processes, is the classic target of the study initiatives in the management field, as their combination might transmute into a higher macro analysis level, which in the present essay refers to what is known as organizational resilience.

2.2 Organizational resilience

Authors such as Horne (1997), Horne and Orr (1998), Mallak (1998), and Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003) attributed to organizational resilience a definition focused on the “bouncing back” capacity, emphasizing organizational coping mechanisms that cause the re-establishment of the previous situation so that the organization directs its efforts only “to reestablish a strong fit between the firm and a new reality while simultaneously avoiding or limiting dysfunctional or regressive behaviors” (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011, p.244).

From another perspective, organizational resilience is seen as thriving, as it extends beyond recovery and includes the development of new capacities and the expansion of abilities that allow the exploration of opportunities and the construction of competences to deal with future adversity (Coutu, 2002; Lengnick-Hall &Beck, 2003; Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007).In this sense, Lengnick-Hall et al. (2011, p.244) explained that: “organizational resilience is seen as thriving (…) [and] organizational resilience is tied to dynamic competition, and a firm’s ability to absorb complexity and emerge from a challenging situation stronger and with a greater repertoire of actions to draw from than were available before the disruptive event”.

Coutu (2002), Hamel and Valikangas (2003), and Lengnick-Hall and Beck (2003) contributed to the construction of an organizational resilience definition as the ability of an organization to develop situational answers to disruptions that represent potential threats to the organization’s survival and that actually make it possible for the organization to capitalize its development in such situations, engaging itself in transforming and restoring the activities of its responsive capacity.

The literature on socio-ecological systems indicates that, although resilience is an emerging property of complex adaptive systems and is linked to its capacity to respond to the environment, “the resilience of a system needs to be considered in terms of the attributes that govern the system’s dynamics” (Walker et al., 2004, p.1). With reference to socioecological systems (SESs), there are three attributes: resilience, adaptability, and transformability. “Resilience is the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks... Adaptability is the capacity of actors in the system to influence resilience (in a SES, essentially to manage it)... Transformability is the capacity to create a fundamentally new system when ecological, economic, or social structures make the existing system untenable” (Walker et al., 2004, p.1).

A distinction between resilience and adaptability on one side and transformability on the other side puts resilience and adaptability within the dynamics of a certain system and transformability within the capacity to alter the nature of the mentioned system (Walker et al., 2004). Lengnick-Hall et al. (2011), considering flexibility as the ability to change in a relatively short period and with low costs, agility as the ability to develop and apply fast competitive manoeuvres, and adaptability as the ability to re-establish the fit with the external environment, stated that, between the organizational resilience construct and these three attributes, although convergence points exist, there are important distinctions to be made: “First, a need for resilience is triggered by an unexpected event. Flexibility and agility are often part of a firm’s on-going repertoire of strategic capabilities leading to increased maneuverability. Second, resilience incorporates renewal, transformation, and dynamic creativity from the inside-out. Adaptability, in contrast, emphasizes the need for environmental fit from an outside-in perspective and often presumes a new, externally determined equilibrium is the desired state. Third, while characteristics such as flexibility, adaptation, improvisation, and agility may contribute to an organization’s capacity for resilience, none of these capabilities is sufficient on its own to achieve it”(Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011, p. 244).

Analysed collectively, the literature on organizational resilience suggests that resilient organizations present a series of important characteristics, as follows (Denhardt &Denhardt, 2010, p.338):

i) Redundancy or capacity excess: allowing an organization to survive, even if one component fails, and tolerating honest mistakes;

ii) Robustness: active and vigorous organizations that promote the physical and mental health of their employees;

iii) Flexibility: organizations that wish and expect to experiment with new approaches instead of counting on standard operational procedures only;

iv) Reliability: a healthy and functional infrastructure that provides access to reliable and precise data as well as to the management of resources;

v) Trust and respect: aspects of the organizational culture and management style that have an impact on the method of dealing with honest mistakes (not punishing them).

For Denhardt and Denhardt (2010), leaders and managers in all organizations should continually seek the development of resilience, not only when they are facing crises or internal and external disasters. After all, in the performance of these functions, they are responsible for leading the organization, for the implementation of changes, and for providing the necessary support through the symbolic apparatus (Motta, 2007), considering the organizational culture as an intangible resource and as the element responsible for mediating the relation between the formally conceived management model and the tangible resources, including the organizational system elements (persons and processes) (Aktouf, 2004).

3. Organizational resilience and the proposition of an analysis model

The conception of resilience as a relative and circumstantial capacity envisages attempts to answer the question of how resilience qualities are acquired, placing resilience under the lenses of a process perspective. According to Denhardt and Denhardt (2010), organizational resilience encompasses both the resilience of individuals and the resilience of a system, a conceptual approach utilized in ecology, which refers to the capacity of natural systems to recover from environmental pressures in such a way that the system’s sustainability is not compromised (Horne, 1997; Walker et al., 2004). Referring to the organization, the system conception is similar to a social system that is being constructed; that is, organizations are socially constructed, based on elements such as power, resources, authority, rules, and procedures (Denhardt & Denhardt, 2010, p.335). The ability to construct meaning allows organizations (of persons) to change the configuration (of the system) and move between organizations. Thus, enhancing the system perspective, organizations are comprised of human actors whose behaviours, individually and collectively, contribute to fostering or hindering organizational resilience.

Thus, if organizational resilience is defined as the capacity to recover (bounce back) from adversity, which varies from disasters to power disputes, passing through turnover crises, so that the organization becomes more flexible and prepared to adapt itself in the face of future adversity, organizational resilience encompasses both the resilience of individuals and the resilience of the system, which counts on the adaptive answer of the individuals and the organization when confronted with systematic discontinuities and major disruptions (Denhardt & Denhardt, 2010). In this way, both the individual capacities used collectively and the aspects related to the system are covered by the organizational resilience concept.

Recovery, positive adaptation to adversity, and balanced sustainability (physical, emotional, and systemic) are elements of the concept of resilience, according to many authors, such as Denhardt and Denhardt (2010), Lengnick-Hall and Beck (2003), Masten and Wright (2010), Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003), and Zautra et al. (2010). When the question was asked about how an individual acquires the characteristics or qualities that make both the process and the result (resilience) feasible (Luthar et al., 2000), it was stated that these elements allow resilience to be studied simultaneously from the perspective of a dynamic process and a final state (or result) - of positive adaptation and overcoming - observed after the exposure to adversity (Waller, 2001).

The definition by Waller (2001, p.290) expresses such an approach in a significant manner. She defined human resilience as “a product - multidetermined and always mutable - of strengths that interact within a determinate ecosystemic context”. Thus, resilience as a cause - exposure to adversity - and result - positive adaptation - cycle can be supported in a comprehensive and multifaceted concept.

Thus, we suggest the following organizational resilience concept: it is the procedural, dynamic, and ecosystemic capacity activated by persons (individual resilience) and processes (systemic resilience) in the face of adversity for the generation of a response, which allows the recovery of balance and the performance of healthy adaptation, through the activation of elements or assets in the subjective or internal and objective or external plans, which might be reinforced or renewed during the process, guaranteeing the sustainability of the resilient result and/or the expansion of the resilience capacity.

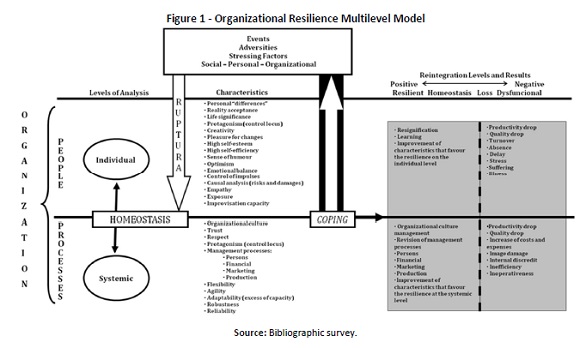

With this concept and considering the individual and systemic resilience elements, as well as the contextual aspects that permeate the relations that occur on the micro and macro levels of the analysis, an analysis model of organizational resilience is suggested in Figure 1.

Thus, this model allows the observation and analysis of organizational resilience as a consequence of the integration of two components, persons and processes, which signalizes two analysis levels, individual and systemic, and which might be observed both in its totality and in its parts; this can be investigated in greater depth in future research, as suggested in the following section.

4. Research perspectives and final considerations

From the suggested model, research possibilities can be perceived both from the methodological point of view and from the thematic connection perspective.

4.1 Methodological research perspectives on organizational resilience

Aimed at the amplification and deepening of the topic under study and the possible cuttings in terms of focuses and emphases, we suggest the performance of descriptive and comparative research, on both the individual and the organizational resilience level, to analyse the elements presented in the model further, aiming to expand its robustness. Besides, the inclusion of organizations in the same activity sector might promote the identification, comprehension, and comparison of the aspects involved in the micro, meso and macro levels, which are delineated in the proposed model. On the other hand, a greater diversity of studies, with organizations in several productive sectors, including the public and the third sector, might also promote such amplitude and the revealing of facets and peculiarities that are directly related to the elements and to the new resilience results under the mentioned levels.

Due to the development stage of the research on the construct in Brazil, we suggest conducting research following qualitative approaches, as they seek the comprehension of meanings and relations subjacent to situations - in this case, events, adversity, and pressures - that might be described by the approached labourers as well as by observations of data from a survey of documents, protocols, and so on in the organizations (Cozby, 2003). With the development of research following these patterns, perspectives for scale validation are made possible, thus allowing the collection of differentiated data, that is, in a quantitative approach, and from this point on the ability to expand the generalization capacity of the findings, as such an approach usually favours measurement and comparison (Collis & Hussey, 2005). In this sense, methodological triangulation might be extremely helpful in the study of resilience, considering the observed analysis levels and the mixture of amplitude (quantitative approach) and depth (qualitative approach) that the combination of complementary methods might promote, as emphasized by Demo (2002).The objective of qualitative research is to reveal the less formal aspects of the phenomenon in question, although without considering its quantitative facet, as such a dichotomy, according to the author, is not real. For him, each quantitative historical phenomenon that involves human beings contains a qualitative dimension; the qualitative dimension, on the other hand, is historical and maintains, in this way, the material, temporal, and spatial contexts. The author concluded that the absolute dichotomization among such facets is a conceptual fiction.

Considering such approaches, we move on to the data collection. In qualitative research, the most common approaches are documental surveys, interviews (with several different scripts, i.e. non-structured, semi-structured, or structured), and direct observation, according to the standardization of Bruyne et al. (1977). The studies in Brazil have shown that complementary research techniques can also be useful, as well as projective techniques, in the sense of acquiring data that are not detailed in interviews or in surveys.

Considering the subject in question, organizational resilience, a documental survey can be undertaken via labourers’ data, which are made available in the human resource area or from other institutions with which the mentioned area holds dialogues (associations or professional councils, trade unions, the Ministry of Labour, etc.), and via data from the organization, such as projects, strategic planning, determination of results, accounting data, and so on. Interviews, on the other hand, can be performed with labourers on different hierarchical levels, considering the peculiarities of the managerial function, besides considering other differences that have been a target of concern within the organizations, such as gender differences, sexual orientation, age groups, skin colour, and so on, as they already involve ample debates in the Brazilian society.

The reasons for and manners of entering and leaving the research field are also important aspects to be observed in a study on resilience, considering the sensibilities that it involves: persons and lives are in the target scope, and they might not be simply ignored. Formally, data saturation (qualitative methods) and sampling (quantitative methods) criteria are considered to be “minimum” arguments to ensure coherence and consistency in academic research. Besides, the orientations and requirements prescribed under Resolution 466 of the National Health Council (Brazil), which deals with human research in the country and orientates the activities of the research ethical committees dispersed throughout the country, are being observed increasingly each day, even considering the minimal or non-existent risks, of any nature, of approaching such purposes in scientific research, even in the applied social sciences, as is the case of the administration.

The treatment of the data, on the other hand, is performed according to their nature. Thus, data derived from secondary sources, in the case of a documental survey, are usually submitted to documental analysis; concerning primary data, those arising from qualitative methods are normally treated through content analysis and/or discourse; and those with a quantitative character are submitted to statistical treatment, the refinement level of which might vary from the objectives defined within the research scope (Collis &Hussey, 2005).

4.2. Perspectives and Thematic Connections in the Research on Organizational Resilience

The organizational resilience construct might appear on the levels presented in the model, in an integrated manner, or, depending on the research pruning, on the parts that compose it. Besides, some possibilities might be demarcated, considering the research initiatives on the subject in the country, as follows:

a) on the individual level, it would be interesting to research resilience elements in professionals:

□ of the same organization, in similar organizations, and in organizations of several sectors (private, public, mixed, nonprofit organizations, cooperatives, associations, etc.), for immediate comparison purposes;

□ of the same organization but in different sectors or on different hierarchical levels, calling the attention to the questions relating to the exercise of the managerial function;

□ with different employment relationships, considering the advance of outsourcing processes, including those in the legal ambit, as well as in self-employment and informal work;

□ in several organizations, stereotyped as “different”, considering the previously mentioned differences, such as gender, sexual orientation, age group, skin colour, and so on, envisaging possible improvements in policies and practices for personnel administration;

□ submitted to undeniable power relations that permeate all types of organization and their coping forms, including those considered to be non-satisfactory, which might end in sickness or actions at law entered in view of psychological harassment;

□ in differentiated professions, reflected in their market valorization, both in symbolic and in remuneration terms;

□ and their relations with identity configurations on several observable levels;

b) on the systemic level: processes relating to human resource management, including policies and practices, the differences between individuals, and improvement perspectives, as well as team management and leadership styles; financial management; marketing management; and production management;

c) on the organizational level: relating the resilience macro vision to sustainability and innovation practices, their essential competencies, dynamic capabilities, management models, organizational learning, social responsibility, image management, and so on.

The purpose of proposing the present research agenda was to contribute in the following ways: first, academically and conceptually, envisaging the sustaining of the delimitation, albeit partial and temporary, of the construct and contributing to its debate; and, second, pragmatically, envisaging supporting labourers and organizations with elements that can be useful in the processes that are involved directly and indirectly with organizational resilience, both on the individual and on the systemic levels, as presented in the proposed model.

Far from any presumption of completing any discussions about this matter, the intention of the present essay was to contribute to the debate regarding a construct that comprises highly complex processes, involving differentiated analysis methods, which is subject to logics that are not always clear and precise, both for the individual and for the organization, and the ample methods considered.

REFERENCES

Aktouf, O. (2004). Pós-globalização, administração e racionalidade econômica. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Antoniazzi, A. S., Bandeira, D.R. & Dell’Aglio, D.D. (1998). O conceito de coping: uma revisão teórica. Estudos de Psicologia, 3(2), 273-294. [ Links ]

Bruyne, P., Herman, J., Schoutheete, M. (1977). Dinâmica da pesquisa em ciências sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Francisco Alves. [ Links ]

Burnard, K. & Bhamra, R. (2011). Organisational resilience: Development of a conceptual framework for organisational responses. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18), 5581-5599. [ Links ]

Carneiro, R. C. C. (2015). A representação do perfil profissional demandado pelas organizações contemporâneas na perspectiva do pop-management. Rio de Janeiro: FGV. [ Links ]

Carver, C. S. (1998). Resilience and thriving: Issues, models, and linkages. Journal of Social Issues, 54(2), 245-266. [ Links ]

Charney, D. S. (2004). Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability Implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. FOCUS: The Journal of Lifelong Learning in Psychiatry, 2(3), 368-391. [ Links ]

Collins, J. C., & Porras, J. I. (1994). Built to last: Successful habits of visionary companies. New York, NY: Harper Business.

Collis, J. & Hussey, R. (2005). Pesquisa em administração. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Correio, F. M. P., Correio, L. C. B., & Correio, A. P. (2018). Identidade, Planejamento e Resiliência: Um estudo sobre comprometimento de carreira em estudantes de graduação em administração. Revista de Carreiras e Pessoas, 8(1), 61-73. [ Links ]

Coutu, D. L. (2002). How resilience works. Harvard Business Review, 80(5), 46-56. [ Links ]

Cozby, P. C. (2003). Métodos de pesquisa em ciências do comportamento. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Davel, E. & Melo, M. C. O. L. (2005). Singularidades e transformações no trabalho dos gerentes. In E. Davel, & M. C. O. L. Melo (Eds),Gerência em ação (pp. 29-65). Rio de Janeiro: FGV. [ Links ]

Demo, P. (2002). Complexidade e aprendizagem. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Denhardt, J. & Denhardt, R. (2010). Building organizational resilience and adaptive management. In J.W. Reich, A.J. Zautra, & J.S. Hall (Eds), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 333-349). New York/London: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Galende, E. H. (2004). Subjetividad y resiliencia: del azar y la complejidad. In A. Melillo, E. N. S. Ojeda,& D. Rodríguez (Eds),Resiliencia y subjetividad (pp. 23-61). Buenos Aires: Paidós. [ Links ]

Grotberg, E. H. (2005). Introdução: Novas tendências em resiliência. In A. Melillo, E. N. S. Ojeda (Eds), Resiliência: descobrindo as próprias fortalezas (pp. 11-22). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Grotberg, E. H. (2006). La resiliencia en el mundo de hoy. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Hamel, G. & Valikangas, L. (2003). The quest for resilience. Harvard Business Review, 81 (9), 52-65. [ Links ]

Hill, L. A. (1993). Novos gerentes: assumindo uma nova identidade. São Paulo: Makron Books. [ Links ]

Horne, J. F. I. (1997). The coming age of organizational resilience.Business Forum, 22(2/3/4), 24-28. [ Links ]

Horne, J. F. I. & Orr, J.E. (1997). Assessing behaviors that create resilient organizations. Employment Relations Today, 24(4), 29-39. [ Links ]

Infante, F. (2005). A resiliência como processo: uma revisão da literatura recente. In A. Melillo, &E. N. S. Ojeda (Eds), Resiliência: descobrindo as próprias fortalezas (pp. 23-38). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Kahn, W. A., Barton, M. A., Fisher, C. M., Heaphy, E. D., Reid, E. M. & Rouse, E.D. (2018). The geography of strain: Organizational resilience as a function of intergroup relations. Academy of Management Review, 43(3), 509-529. [ Links ]

Kamlot, D. (2017). Resiliência organizacional e marketing social: uma avaliação de fundamentos e afinidades. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, 15, 482495. [ Links ]

Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Lengnick-Hall, C. A. & Beck, T.E. (2003). Beyond bouncing back: The concept of organizational resilience. Paper presented at National Academy of Management meetings. [ Links ]

Lengnick-Hall, C. A., Beck, T. E. & Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2011). Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 21(3), 243-255. [ Links ]

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D. & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71, 543-562. [ Links ]

Mallak, L. (1998). Putting organizational resilience to work. Industrial Management, 40(6), 8-13. [ Links ]

Martineau, S. (1999). Rewriting resilience: A critical discourse analysis of childhood resilience and the politics of teaching resilience to “kids at risk”. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. [ Links ]

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227. [ Links ]

Masten, A. S. & Wright, M.O.D. (2010). Resilience over the lifespan: Developmental perspectives on resistance, recovery, and transformation. In J.W. Reich, A.J. Zautra, & J.S. Hall (Eds), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 213-237). New York, London: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Melillo, A. (2004). Sobre la necesidad de especificar un nuevo pilar de la resiliencia. In A. Melillo, E.N.S. Ojeda,& D. Rodríguez (Eds), Resiliencia y subjetividad (pp. 77-90). Buenos Aires: Paidós. [ Links ]

Motta, P. R. (2007). Gestão Contemporânea. Rio de Janeiro: Record. [ Links ]

Paiva, K. C. M. (2013). Das “competências profissionais” às “competências laborais”. Tourism & Management Studies, 2, 502-510. [ Links ]

Raasch, M., Silveira-Martins, E. & Gomes, C. C. (2017). Resiliência: Uma revisão bibliométrica. Revista de Negócios, 22(4), 40-55. [ Links ]

Reed, M. (1997). Sociologia da gestão. Oeiras: Celta. [ Links ]

Richardson, G. E. Neiger, B. L., Jensen, S. & Kumpfer, K. L. (1990). The resiliency model. Health Education, 21(6), 33-39. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, S. B., Child, J. & Luz, T. R. (2004). Aprendizagem contestada em ambiente de mudança radical. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 44(1), 27-43. [ Links ]

Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity: protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 147, 598-611. [ Links ]

Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms.American journal of orthopsychiatry, 57 (3), 316. [ Links ]

Rutter, M. (2007). Resilience, competence, and coping. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(3), 205-209. [ Links ]

Shin, J., Taylor, M. S. & Seo, M. (2012). Resources for change: The relationships of organizational inducements and psychological resilience to employees’ attitudes and behaviors toward organizational change. Academy of Management Journal, 55(3), 727-748. [ Links ]

Skodol, A. E. (2010). A resilient personality. In J. W. Reich, A. J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 112-125). New York/London: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Sonaglio, K. E. (2018). Aproximações entre o turismo e a resiliência: Um caminho para a sustentabilidade. Turismo: Visão e Ação, 20(1), 80-104. [ Links ]

Stuart, H. C. & Moore, C. (2017). Shady characters: The implications of illicit organizational roles for resilient team performance. Academy of Management Journal, 60(5), 1963-1985. [ Links ]

Sutcliffe, K. M. & Vogus, T .J. (2003). Organizing for resilience. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton & R. E. Quinn (Eds), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 94-110). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. [ Links ]

Tavares, J. (2001). A resiliência na sociedade emergente. In J. Tavares, Resiliência e educação (pp. 43-76). São Paulo: Cortez. [ Links ]

Timoshenko, S. P. (1976). Resistência dos materiais. Rio de Janeiro: LTC. [ Links ]

Tusaie, K. & Dyer, J. (2004). Resilience: A historical review of the construct. Continuing Education, 18(1), 3-8. [ Links ]

Vasconcelos, I. F. F. G., Cyrino, A. B., Carvalho, L. A. & D’Oliveira, L. M. (2017). Organizações pós-burocráticas e resiliência organizacional: a institucionalização de formas de comunicação mais substantivas nas relações de trabalho. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, 15, 377-389. [ Links ]

Vasconcelos, I. F. F. G. & Pesqueux, Y. (2017). Resiliência organizacional e teoria da ação comunicativa: Uma proposta de uma agenda de pesquisa. Revista de Administração da Unimep, 15(4), 163-178. [ Links ]

Vieira, A. A. & Oliveira, C. T. F. (2017). Resiliência no trabalho: uma análise comparativa entre as teorias funcionalista e crítica. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, 15, 409-427. [ Links ]

Walker, B., Holling, C., Carpenter, S. R. & Kinzig, A. P. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2), 5. [ Links ]

Waller, M. (2001). Resilience in ecosystemic context: Evolution of the concept. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(3), 290-297. [ Links ]

Weick, E. & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007) Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty. San Francisco/CA: Jossey-Bass.

Yunes, M. A. M. & Szymanski, H. (2001). Resiliência. In J. Tavares, Resiliência e educação (pp. 13-42). São Paulo: Cortez. [ Links ]

Zautra, A. J., Hall, J. S. & Murray, K. E. (2010). Resilience. In J. W. Reich, A. J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 3-33). New York/London: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Received: 12.11.2018

Revisions required: 21.02.2019

Accepted: 14.05.2019