Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tourism & Management Studies

Print version ISSN 2182-8458On-line version ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.14 no.Especial Faro 2018

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2018.14SI106

HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Satisfaction and loyalty in the all-inclusive system in Cape Verde

Satisfacción y lealtad en el sistema todo incluido en Cabo Verde

Juan Antonio Jimber Del Río1, Jesús Claudio Pérez-Gálvez2, Francisco Orgaz-Agüera3, Virginia Navajas-Romero4, Tomás López-Guzmán5

1University of Córdoba, Faculty of Labour Sciences, C/ Adarve, nº 30, 14071, Córdoba, Spain, jjimber@uco.es

2University of Córdoba, Faculty of law and Business, Plaza Nueva s/n, 14002, Córdoba, España, dt1pegaj@uco.es

3Technology University of Santiago, Av. Estrella Sadhalá, n. 75, Santiago, Dominican Republic., franorgaz@utesa.edu

4University of Córdoba, Faculty of Labour Sciences, C/ Adarve, nº 30, 14071, Córdoba, Spain, z42narov@uco.es

5University of Córdoba, Faculty of Labour Sciences, C/ Adarve, nº 30, 14071, Córdoba, Spain, tomas.lopez@uco.es

ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to analyse satisfaction and loyalty in the All- Inclusive system in Cape Verde, one of the main destinations of sun and beach in Africa. The methodology used was based on surveys conducted with tourists. The data from this research have been analysed with SPSS 23 and AMOS IBM SPSS 23. The results of this research have shown that in order to achieve the loyalty of tourists, the role of both the agents and those responsible for the destination is very important; therefore, they should attract tourists with the right socio- demographic profile, and second, improve the knowledge and the attitude of the visitors regarding the different attractions of the "all- inclusive” system. Thus, the value perceived by the tourists has a bearing on satisfaction, helping to reinforce loyalty to the destination.

Keywords: All-inclusive system, attitude, perceived value, satisfaction, loyalty, structural equations, Cape Verde.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este artículo es analizar la satisfacción y la lealtad en el sistema todo incluido en Cabo Verde, uno de los principales destinos de sol y playa en África. La metodología utilizada se ha basado en la realización de encuestas a turistas. Los datos de esta investigación han sido analizados con SPSS 23 y AMOS IBM SPSS 23. Los resultados de la investigación han mostrado que, para logar la lealtad de los turistas, el papel tanto de los agentes como su responsabilidad en el destino son muy importantes; asimismo, primero, se debería atraer a los visitantes con un determinado perfil sociodemográfico y, segundo, mejorando el conocimiento y la actitud de los visitantes hacia las diferentes atracciones con el sistema todo incluido. Por tanto, el valor percibido por los turistas está relacionado con la satisfacción y, por tanto, ayuda a reforzar la lealtad al destino.

Palavras-chave: Sistema todo incluido, actitud, valor percibido, satisfacción, lealtad, ecuaciones estructurales, Cabo Verde.

1. Introduction

The analysis of the profile of the tourist who visits the different islands is one of the most recurring themes within the scientific literature (Bryan, 2001; Craigwell, 2007; Roberts & Lewis- Cameron, 2010) since, following Correia and Pimpao (2008), the islands are the second most preferred destination for vacations, only behind the category of historic cities. Therefore, among the reasons for which the tourist chooses to spend his/her holidays on islands resides, in the first place in the climate and, in second place in an element of a subjective nature such as the existence of a physical separation from the continents which makes it a special and attractive place for travellers who, in this way, may disconnect from their daily routine (Cameron & Gatewood, 2008). There are different types of islands. Among them we find islands that are countries, and whose economic model has evolved from the exporting of products corresponding to the primary sector to the articulation of tourism development based mainly on mass tourism (McElroy, 2003). Within this latter type of insular States, we find small islands corresponding to Developing Countries which are called SIDS (Small Island Developing States), and which are characterized by a population of less than a million inhabitants and an extension not over 5,000 km2. The SIDS are very vulnerable economically, among other reasons, due to the inexistence of economies of scale, the scarcity of resources, the insularity, the low demographic proportion and the scant extension of their domestic markets (Scheyvens & Momsen, 2008a). However, in a positive sense, the tourism business in these islands is conceived as a multidisciplinary product that impacts the entire society and that permits easier coordination among the different social and economic agents. In the last decade Cape Verde has taken a qualitative and quantitative economic leap that has allowed it to pass to the status of Middle Income Country. This leap is due mainly to the great development of tourism that the country has had, accompanied, obviously, by the construction industry. The evolution of the tourism sector in Cape Verde is analysed through different studies of both a quantitative and qualitative character. Among the studies of a quantitative profile we can highlight those by Mitchell, Parkin, Kroh, Fritz, Wyman et al. (2008), McElroy and Hamma (2010), Twining-Ward (2010), the Government of the Canary Islands (2009), the Direcção Geral do Turismo of Cape Verde (2009) and the World Bank (2010). Furthermore, and from a qualitative perspective, we can highlight the work of Correia and Pimpao (2008) whose approach is on the perception that the tourists have about this tourist destination, and the study of Melián-González and García-Falcón (2003) where a comparative analysis is presented on the competitiveness of fishing tourism in four nearby geographic areas (Canary Islands, Madeira, Azores and Cape Verde).

The principal objective of this paper is to contribute to the research of the tourism industry in Cape Verde through a study that, through methodology based on structural equation modelling, it constructs indicators of the quality perceived by the tourists as well as the loyalty that they present. This model allows estimating multiple dependency relationships and representing in them variable non-observable or latent relationships, taking into account the measuring error in the estimation process (Reisinger & Turner, 1999). In order to achieve this objective, this paper is structured, after this introduction, in a second section where a review of the literature is presented; in the third section the study area and the methodology applied are shown, and we can find the results of the research in the fourth section. This paper ends with the conclusions of the research and the references used.

2. Review of the literature

The origin of the All-Inclusive System (AIS) is found in the fieldwork of England during the 1930’s and afterwards in the Club Méditerranée in the 1950’s (Issa and Jayawardena, 2003). But its greatest development was produced in the Caribbean, beginning with Jamaica, in the 1970’s, uniting, in addition to this accommodation system, the image of sun and beach that identifies this geographic area (Chambers & Airey, 2001; Issa & Jayawardena, 2003; Ayik, Benetatos & Evagelou, 2013). Currently the AIS is largely implemented in the Caribbean. Nonetheless, it has also been implemented in different Mediterranean countries, both European and African, and in some geographic areas of Africa and Southeast Asia (mainly in Indonesia and Thailand) (González Herrera & Palafox Muñoz, 2007), with Europe and North America being the principal source countries for this type of tourists (Anderson, 2010), who are characterized by having a medium economic income (Ayik et al., 2013). Along with this, the concept of All-Inclusive, in addition to the coastal areas, in recent years is also being implemented in other types of tourism such as the cruises (Issa & Jayawardena, 2003) and its marketing associated to some type of tourism package (Wong and Kwong, 2004). The AIS is an important innovation in the tourism product directed, basically, at international markets and is based, above all, on the minimization of the monetary transactions carried out during the holidays. The fundamental characteristics of this system are based on including in the final price that the tourist pays, generally in his place of residence, elements such as the accommodations, food, drinks or, even, a series of complementary tourist services (Wong & Kwong, 2004; González Herrera & Palafox Muñoz, 2007) and it especially functions, as we indicated earlier, in certain coastal destinations of sun and beach (Anderson, 2010). Furthermore, it usually functions in destinations with low citizen safety and in those places in which there is no attractive complementary offer outside the hotel, especially of restaurants and recreation (González Herrera & Palafox Muñoz, 2007), although in recent years it has extended towards regions where there is a wide complementary offer as may be certain areas of European countries, such as the case of Spain and Portugal, in which an important debate has been generated among the tourism managers on the positive and negative effects of this system in these geographic areas. Among the positive effects of the AIS we find an increase in the income of the tour operators and the travel agencies, the creation of opportunities of trips for tourists with not very high costs, an increase in the ratios of occupancy of the resorts, the introduction of another type of tourism products and the simplification of the commercial relations between the hotel and the guests (Alegre & Pou, 2006; Özdemir, Ehtiyar, Çizel, Çizel & Içigen, 2012). And as negative effects we find the drop in the quality of the tourism product, the decrease in the motivation of the hotel personnel, the little interaction among the tourists, basically foreigners, and the local community (Çiftci, Düzakin & Önal, 2007; Ozdemir Aksu, Ehtiyar, Çizel, & İçigen, 2012) and that this system is not appropriate for small hotels since a minimum number of rooms is needed, calculated at around 150 rooms (Anderson, 2010). The AIS is a tourism producer and that implies, therefore, an important modification of the tourism services at the destination (Alegre & Pou, 2006), mainly due to the near disappearance of the restaurant sector, as a consequence of a modification in the flow of services that are offered in the destination, since the majority of them are supplied by the hotel establishment itself. In this regard, the quality of the facilities of the hotel itself, including in a significant manner the gastronomy that is offered to the tourists in the hotel and the quality of the drinks that are served in the hotel without additional cost, as they are already paid for in the place of origin, is fundamental for the tourist’s satisfaction (Çiftçi, Düzakin & Önal, 2007; Ayik et al., 2013), and with aspects such as the cultural, natural or historic elements of the destination not being as important in the degree of satisfaction of the tourist. Even these aspects are not considered as significant at the time of choosing the traveller’s place of rest (Ayik et al., 2013). The AIS is being consolidated in many destinations due to the prior knowledge that the consumer has of what the trip is going to cost him before starting it (Çizel, Çizel, Sarvan & Ozdemir, 2013), the important role that the intermediaries have in this system (Çizel et al., 2013) and that this type of product is directed at different types of clients such as couples, families, young people, retired persons and so on (Çiftçi et al., 2007). Furthermore, this system implies an opportunity for the development of Developing Countries (Çizel et al., 2013), although one of the basic aspects to analyse, and debate, as we have explained previously, is the relationship that exists between the resorts and the companies supplying the goods and services belonging to the local community (Anderson, 2010) in order to determine the economic flows that would finally be found in the local companies. The scientific literature documents AIS studies in Spain (Alegre &d Pou, 2006; Anderson, 2012), Romania (Condratov, 2014), Turkey (Ayik et al., 2013; Özdemir et al., 2012), Jamaica (Smith & Spencer, 2011), Dominican Republic (Moreno Gil, Celis Sosa & Aguiar Quintana, 2002), other countries of the Caribbean (Chamber & Airey, 2001), Malta (Chapman & Speake, 2011) and Mexico (González Herrera & Palafox Muñoz, 2007).

The relationship between satisfaction and loyalty has been widely discussed in the literature. Oliver (1999) suggests that loyalty is developed in different steps. In the first place, cognitive loyalty is developed. Over time, the emotional and intentional forms of loyalty become factors. For retailers, intentional loyalty is a very desirable result (Keiningham, Aksoy, Williams & Buoye, 2012). Intentional loyalty is based on stable beliefs regarding the quality and value of the service. In addition, it creates strong emotional ties with the service. Satisfaction with the service is considered a necessary condition, although insufficient, for the development of intentional loyalty. Satisfaction is the result of a positive evaluation of the quality and of the value of different elements of the service. The clients compare their actual experiences with the distributor’s service to their expectations and desired results. Therefore, satisfaction will depend on the competitive structure of the market, the degree of differentiation, the participation of the client and the buying experience (Anderson, Fornell & Lehmann, 1994).

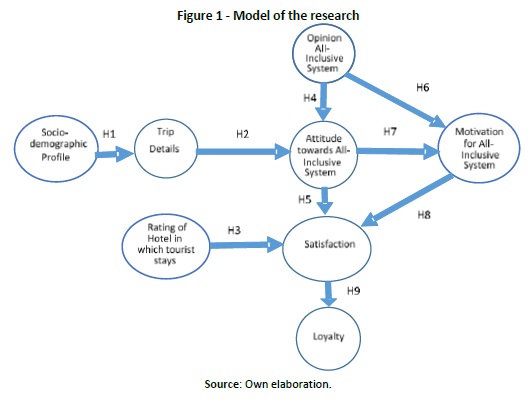

From the above review, the following hypotheses were formed:

H1. There is a significant relationship between the sociodemographic profile of the tourist who prefers the all- inclusive system and his preparation for the trip.

H2. The knowledge of the trip details is significantly related to the attitude of the visiting tourist in the all-inclusive system.

H3. The rating of the hotel in which the tourist stays in the all- inclusive system is significantly related to the visitor’s satisfaction. H4. The opinion of the tourist in an all-inclusive system is

significantly related to his attitude towards it.

H5. There is a significant relationship between the attitude of the tourist who chooses the all-inclusive system and his satisfaction.

H6. The opinion of the tourist who chooses an all-inclusive system is significantly related to the motivation perceived in this system.

H7. The attitude of the tourist who chooses the all-inclusive system is significantly related to the motivation perceived in this system.

H8. There is a significant relationship between the motivation perceived by the tourist who chooses the all-inclusive system and his satisfaction.

H9. There is a significant relationship between the satisfaction of the visitor who chooses the all-inclusive system and his loyalty.

3. Area of study and methodology

Cape Verde is a country located in the Atlantic Ocean and is formed by ten islands (nine inhabited and one uninhabited) which, all together, comprise a total surface area of 4,033 km². In 2007 a Preferential Agreement was signed with the European Union which has allowed it to strengthen its commercial relations with the different countries of this supranational organization and it has also led to its being the receiver of European capital. Consequently, the majority of the investments, both in hotels and in the construction sector, on the most touristic islands of Sal and Boa Vista, come from European capital, mainly Portuguese, Spanish, British and Italian. The total population of the country is around 500,000 persons.

The tourism of Cape Verde is being developed through two completely different paths: first, through the creation of large resorts, generally financed with foreign capital and constructed principally on two islands (Sal and Boa Vista), and based on the AIS; second, through the creation of small tourism companies, managed by the local community and mostly financed by capital sent by the diaspora. This paper is focussed on the island of Sal, traditionally the most touristic island of Cape Verde. Sal Island has an extension of 216 km2, with a population somewhat over 25,000 persons. This island, and more specifically, a geographic area, the city of Santa María, is characterised by the development of tourism based on the resort concept, although it is also having strong real estate development based on residential tourism.

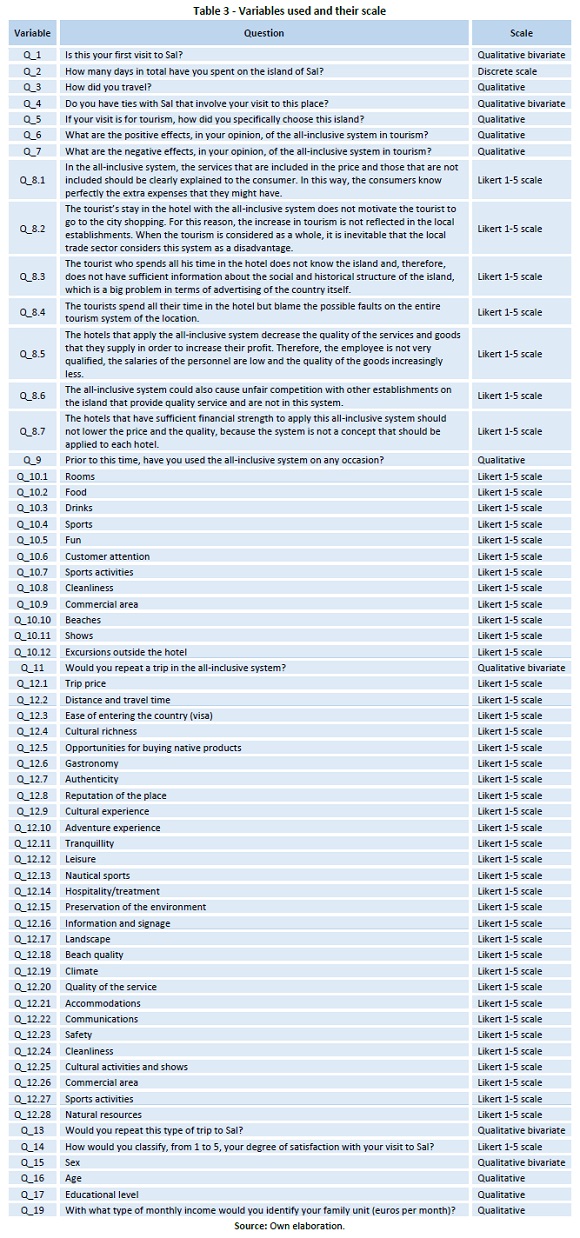

The method chosen for data collection has been personal interviews supported by a structured questionnaire. In this phase, a useful instrument was drawn up with the aim of collecting the information necessary to achieve the objectives of this research. Among the options for the data collection, a closed questionnaire to be self-administered was chosen. With the aim of guaranteeing the validity of the questionnaire, the formulation of the items was based on items selected from previous research (Turner, 2008; Gelbman & Timothy 2010; Yoon, Lee & Lee, 2010; Sullivan, Bonn, Bhardwaj & DuPont, 2012; Zhang & Lei, 2012; Cong, 2016). From this initial set of items, a filtering process was done in two phases. First, a researcher specialized in tourism analysed the proposed items; second, the resulting questionnaire was reviewed by a person responsible for the tourist business in the region. In this way, the validity of the items making up the constructs of the model posed for this research was verified.

Special attention was then given to the translation process of the proposed items from the original English to Portuguese, Spanish, German and French, pursuing their adaptation to the context and their equivalence in the language with regard to their meaning, nuances and connotations. The questionnaire most applied was the one in English. The surveys were done personally with the tourists who visited some of the tourism resources of Sal Island. Prior to the application of the survey, the interviewer informed the tourist of the objective of the research and asked for his collaboration. The tourist completed the questionnaire with complete autonomy and anonymously.

The questionnaire is designed in four clearly differentiated parts. The first deals with the details of the visiting tourist’s trip; the second, the evaluation and the opinions of the visitor regarding the all-inclusive system and the hotel in which he is lodged; the third, the evaluation and opinions of the visitor on the destination in the island of Sal; and fourth, the sociodemographic profile of the tourists.

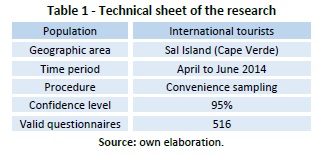

In this way, there were a total number of 19 items, after the filtering process of items through the calculation of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each construct. The fieldwork was done during the months of April to June 2014, by means of convenience sampling. A pretest of 20 surveys was conducted. In total, the number of valid questionnaires was 516, obtaining a confidence level of 95%. Table 1 shows the technical sheet of the research.

The questions of the first part of the questionnaire (trip details) and most of the items related to the sociodemographic profile of the tourist, included in the fourth part of the survey, are closed. The second and third parts of the questionnaire were answered through a Likert five-point scale. The questions were formulated in a positive and negative sense for the items asked in order to avoid acquiescence, which is defined as “the tendency of some subjects to answer (agreeing) regardless of the content of the item”. Cronbach’s alpha index of all the items is 0.941 and, therefore, it is acceptable, since Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) consider a scale acceptable if its Cronbach’s alpha is over 0.7. The data of this research have been tabulated and analysed using the IBM SPSS 23 statistical system, and the estimators and the structural equations with IBM SPSS AMOS 23.

4. Results of the research

In the area of tourism, frequently the variables subject of the study, such as the tourism quality, cannot be measured directly and it is necessary to quantify them from other observable or manifest variables. The objective of this section consists of constructing quality indicators perceived in tourist destinations and loyalty of the tourists through methodology based on structural equation models. These models allow estimating multiple dependency relationships and representing in these relationships non-observable or latent variables, taking into account the measuring error in the estimation process (Reisinger & Turner, 1999).

In the prepared questionnaire, a set of quality indicators perceived from the descriptive viewpoint was developed, based on the knowledge on tourism of sun and beach, and the attitudes towards tourism in the islands, the value that is assigned by the tourist in this type of destination, the loyalty of the visitor towards the destination of sun and beach and the satisfaction and importance declared by the tourists as an approximation of the perceived quality of a destination. The use of the methodology of structural equations, which incorporates latent variables to the analysis and whose values can be used as indicators related to the destination is what make this study different.

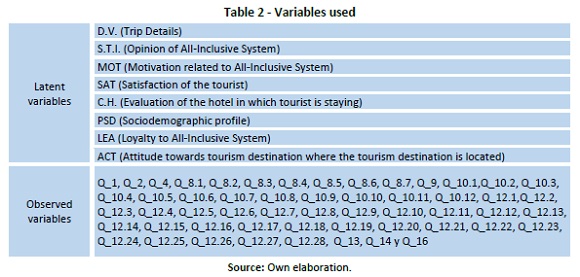

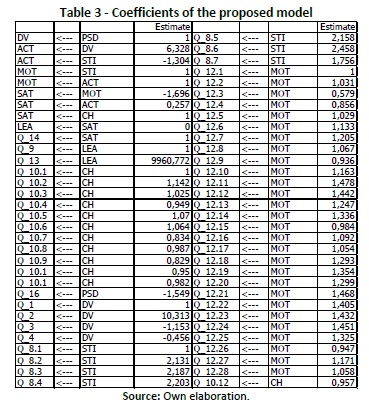

In this respect, an initial model (Model 1) was designed which considers the following observed and latent variables, both exogenous and endogenous (Tables 2 and 3):

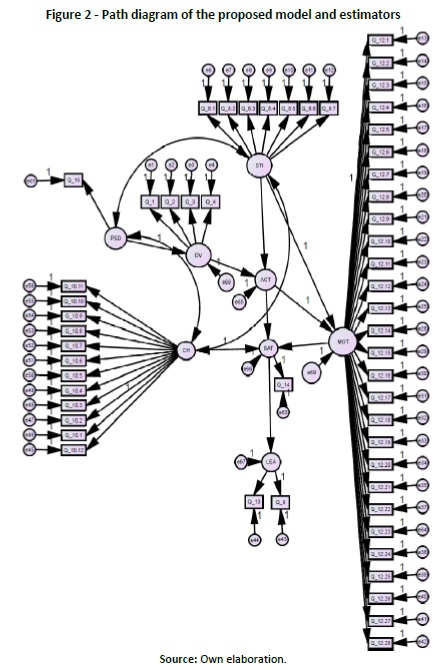

The perturbation terms include the effects of the omitted variables, the measuring errors and the randomness of the specified process. The variation in the perturbation term is denoted by the covariation between the perturbation terms. On the other hand, the regression coefficients represent the relationship that exists between a latent exogenous variable and an endogenous one, those that relate the latent endogenous variables to each other and those that represent the covariation between the latent exogenous variables. In Figure 2 and in Tables 3 and 4, the estimated structural coefficients of the proposed model are shown. The model was estimated by the ULS (Unweighted Least Squares) method. The ULS method is an estimation method of parameters for which it is not established that the observed variables should follow a certain distribution and, therefore, it is recommended for categorical variables and it is based on the matrix of polychoric correlations (Batista Foguet & Coenders Gallart, 2000; Bollen, 1989; Schumacker & Lomax, 1996). In addition to the ULS method, when ordinal variable is handled, other alternative methods are also taken into account. Among them, the RULS method can be highlighted which, according to Yang-Wallentin, Jöreskog and Luo (2010), is a robust variant of the ULS method. Like the latter, RULS also works with a matrix of polychoric correlations, although these correlations are the starting point for subsequently obtaining the matrix of asymptotic covariances (AC) that intervene in its free distribution W matrix.

Model 1 (Figure 2) presents the Path diagram that follows the structure of the initial theoretical model (Figure 1), with the hypotheses to contrast and the structural coefficients estimated by the ULS model once the non-significant variables are eliminated. These variables are the following: Q_5, Q_6, Q_7, Q_11, Q_15, Q_18 y Q_19. Table 3 shows the structural coefficients estimated by the ULS method.

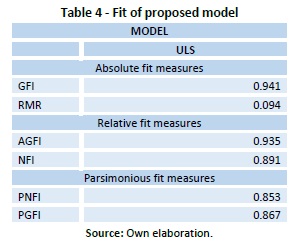

In order to confirm the degree of fit of the proposed model (Table 4), absolute fit measures, relative fit measures and parsimonious fit measures were calculated. The evaluation of the model was done using the following indices: first, Normed Fit Index (NFI) as a measurement of discrepancy between the adjusted model and the base model; second, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), similar to the previous one, and which compares the discrepancies between the adjusted model and the model prior to adjustment; third, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), an indicator prior to the previous one but weighted by a ratio of the degrees of freedom of the base model and adjusted; fourth, Parsimonious Normed Fit Index (PNFI), obtained from the NFI index and weighted by the quotient of the degrees of freedom of the adjusted model and the base model; fifth, Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA) which is obtained as the square root of the ratio of the noncentrality parameter adjusted by the degrees of freedom; and sixth, Square Root of the Root Mean Square Residual (RMR).

As for the absolute fit measures, the GFI measure exceeded 0.9, indicating a good fit and RMR presented a value of 0.095, which is considered an acceptable fit for the model. Some relative fit measures such as the AGFI are sensitive to the number of indicators; however, in this case it exceeded the 0.9 value and was close to the GFI, indicative of a good fit. As for the parsimonious fit measures, PNFI and PGFI are significant from values of 0.06. Therefore, both indices were also significant for the calculated method. Based on the above, it is considered that the model present adequate fit indices.

The results of this research underscore the relationship, the influence and the positive and direct impact on the knowledge, the attitude of the visitor, the perceived value, the satisfaction and the loyalty of the visitor towards the tourism destination of the island of Sal in the all-inclusive system.

The structural coefficients estimated in the model allow us to contrast the starting hypotheses:

H1. There is no significant relationship between the sociodemographic profile and the details of the tourist’s trip in the all-inclusive system since, with an insignificant structural coefficient, the hypothesis is not confirmed due to the fact that the sociodemographic profile does not have significant effects on the details of the trip.

H2. There is a significant relationship between the knowledge of the trip details and the tourist’s attitude towards the all-inclusive system because, with a predetermined structural coefficient in the unit, the significant and positive effect of knowledge of the trip details on the visitor’s attitude towards the all-inclusive system has been presupposed as a premise.

H3. There is a significant relationship between the rating of the hotel in which the tourist stays and the visitor’s satisfaction because, with a predetermined structural coefficient in the unit, the significant and positive effect of the rating of the hotel on the satisfaction perceived by the tourist in the all-inclusive system has been presupposed as a premise.

H4. There is a significant relationship between the tourist’s opinion and the all-inclusive system because, with a significant structural coefficient, the hypothesis is confirmed due to the fact that the tourist’s opinion on the all-inclusive system has a significant negative effect on his attitude towards the all- inclusive system.

H5. There is a significant relationship between the attitude of the tourist towards the all-inclusive system and the visiting tourist’s satisfaction because, with a significant structural coefficient, the hypothesis is confirmed due to higher value of the tourist’s attitude towards the all-inclusive system since it has significant positive effects on the visitor’s satisfaction in the all-inclusive system.

H6. There is a significant relationship between the tourist’s opinion regarding the all-inclusive system and the perceived motivation of the all-inclusive system because, with a predetermined structural coefficient in the unit, the significant and positive effect of the tourist’s opinion with respect to the all-inclusive system on the motivation perceived by the visitor on the all-inclusive system has been presupposed as a premise.

H7. There is a significant relationship between the tourist’s attitude towards the all-inclusive system and the perceived motivation of the tourist of the all-inclusive system because, with a significant structural coefficient, the hypothesis is confirmed due to higher value of the tourist’s attitude towards the all-inclusive system since it has significant positive effects on the visitor’s perceived motivation with respect to the all- inclusive system.

H8. There is a significant relationship between the tourist’s perceived motivation in the all-inclusive system and the visitor’s satisfaction because, with a significant structural coefficient, the hypothesis is confirmed due to the fact that the tourist’s opinion in the all-inclusive system has a significant negative effect on the tourist’s perceived motivation in the all-inclusive system.

H9. There is a significant relationship between the tourist’s satisfaction and the loyalty of the visitor towards the destination in an all-inclusive system because, with a significant structural coefficient, the hypothesis is confirmed due to the fact that the tourist’s opinion in the all-inclusive system has a significant negative effect on the tourist’s perceived motivation in the all-inclusive system.

Conclusions

The results obtained in this paper highlight that the opinion of the tourist lodged in an all-inclusive system has exercised a direct and positive influence on the tourist’s attitude towards the all-inclusive system. A direct and positive relationship is also

shown among the tourist’s attitude towards the all-inclusive system, the motivation and the satisfaction perceived by the client in these services. Despite the fact that in previous research the direct relationship between satisfaction and the intention to return to the destination has not been confirmed sufficiently, given that the tourists prefer new places in their trips, in this paper this relationship is verified, since an important percentage of the persons interviewed (nearly 79%) have affirmed using the all-inclusive system on more than one occasion, despite only 24% having family ties in the tourism destination area.

The importance of measuring the satisfaction variable is derived from its relationship with the client’s loyalty (Galloway, 1998). The variables of satisfaction and loyalty are found to be closely related and the satisfaction is a variable that precedes loyalty (Dick & Basu, 1994). In our paper, the direct and positive relationship between the satisfaction perceived by the client that is lodged using an all-inclusive system and the loyalty of again using this accommodation system, as well as recommending the tourism destination is confirmed.

The academic literature also shows the existence of a positive relationship between the consumer’s satisfaction and loyalty, with the first preceding the second, which is usually measured by the intention of post-purchase behaviour (Henard & Szymanski, 2001). Given that the image a tourist has of a destination is going to influence significantly his intention to return and/or recommend it and even how he evaluates the experience in itself, its management becomes a subject of vital importance for the success of the destination. Furthermore, this importance is reinforced by the fact that the destinations compete basically by means of their image given that, before being visited, the tourists form an image of them which will be the one they bring to the site. On the other hand, their experience in the destination could lead to a modification of the initial perceived image, which only in the case of being positive will manage to strengthen their loyalty. Consequently, the construction of an appropriate image for a destination will determine its capacity to attract and retain tourists.

In view of this situation, the role carried out by the agents and persons responsible for the destination in achieving the loyalty of the tourist is truly important, for which reason they should improve, through different actions, the knowledge and the image of the different tourist attractions of the destination. Only through an adequate coordination and cooperation among these agents can the tourist’s satisfaction be achieved, satisfaction which will help to reinforce the loyalty towards the destination.

As for the limitations of this research, it is centred on the need for obtaining information on the tourism destination, as well as the all-inclusive services, information from the viewpoint of the hotel offer, since this paper only refers to the demand for these services.

As future research lines, the crossing of information between the offer and the demand is proposed, since it would provide information on the equilibrium point in this market, as well as the form of optimizing the resources of the hotel industry that offers all-inclusive services and the product demanded by the

clients, which would lead them to repeat their visit, demonstrating the very sought-after loyalty of the client.

REFERENCES

Alegre, J., & Pou, L. (2006). The length of stay in the demand for tourism. Tourism management, 27(6), 1343-1355. [ Links ]

Anderson, C. (2012). New Zealand’s green tourism push clashes with realities. New York Times, 16, 11-12.

Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C., & Lehmann, D. R. (1994). Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. The Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 53-66. [ Links ]

Anderson, W. (2010). Determinants of all-inclusive travel expenditure. Tourism Review, 65(3), 4-15. [ Links ]

Ayik, T., Benetatos, T., & Evagelou, I. (2013). Tourist consumer behaviour insights in relation to all-inclusive hotel resorts. The case of Anatalya, Turkey. Journal of Tourism Research, 7, 123-142. [ Links ]

Batista Foguet, J. M., & Coenders Gallart, G. (2000). Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales: modelos para el análisis de relaciones causales. [ Links ]

Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 17(3), 303-316. [ Links ]

Bryan, A. (2001). Caribbean tourism: igniting the engines of sustainable growth. Florida: University of Miami. [ Links ]

Cameron, C. M., & Gatewood, J. B. (2008). Beyond sun, sand and sea: The emergent tourism programme in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 3(1), 55-73. [ Links ]

Chambers, D., & Airey, D. (2001). Tourism policy in Jamaica: A tale of two governments. Current Issues in Tourism, 4(2-4), 94-120. [ Links ]

Chapman, A., & Speake, J. (2011). Regeneration in a mass-tourism resort: The changing fortunes of Bugibba, Malta. Tourism Management, 32(3), 482-491. [ Links ]

Çiftçi, H., Düzakin, E., & Önal, Y. B. (2007). All-inclusive system and its effects on the Turkish tourism sector. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 5(3), 269-285. [ Links ]

Çızel, R. B., Çızel, B., Sarvan, F., & Özdemır, B. (2013). Emergence and Spread of an All-Inclusive System in the Turkish Tourism Sector and Strategic Responses of Accommodation Firms. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 14(4), 305-340.

Condratov, I. (2014). All-inclusive system adoption within Romanian tourist sector. Ecoforum Journal, 3(1), 13-32. [ Links ]

Cong, L. C. (2016). A formative model of the relationship between destination quality, tourist satisfaction and intentional loyalty: An empirical test in Vietnam. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 26, 50-62. [ Links ]

Correia, A., & Pimpao, A. (2008). Decision-making processes of Portuguese tourist travelling to South America and Africa. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 2(4), 330-373. [ Links ]

Craigwell, R. (2007). Tourism competitiveness in small island developing states. New York: United Nations University, World Institute for Development Economics Research. [ Links ]

Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 22(2), 99-113. [ Links ]

Direcção Geral do Turismo de Cabo Verde (2009). Plano Estratégico para o desenvolvimento turístico de Cabo Verde. Praia: Servicio de publicaciones del Ministério de Economia, Crescimiento e competitividade. [ Links ]

Galloway, L. (1998). Quality perceptions of internal and external customers: a case study in educational administration. The TQM Magazine, 10(1), 20-26. [ Links ]

Gelbman, A., & Timothy, D. J. (2010). From hostile boundaries to tourist attractions. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(3), 239-259. [ Links ]

González Herrera, M., & Palafox Muñoz, A. (2007). Hoteles todo incluído en Cozumel: aproximación hacia la sustentabilidad como elemento competitivo del destino. Revista Turismo em Análise, 18(2), 220-244. [ Links ]

Henard, D. H., & Szymanski, D. M. (2001). Why some new products are more successful than others? Journal of marketing Research, 38(3), 362-375. [ Links ]

Issa, J. J., & Jayawardena, C. (2003). The “all-inclusive” concept in the Caribbean. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 15(3), 167-171.

Keiningham, T. L., Aksoy, L., Williams, L., & Buoye, A. (2012). Why loyalty matters in retailing. In Service Management (pp. 67-82). Springer New York.

McElroy, J. L., & Hamma, P. E. (2010). SITEs revisited: Socioeconomic and demographic contours of small island tourist economies. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 51(1), 36-46. [ Links ]

McElroy, M. W. (2003). The new knowledge management: Complexity, learning, and sustainable innovation. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Melian-Gonzalez, A., & Garcia-Falcon, J. M. (2003). Competitive potential of tourism in destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 720-740. [ Links ]

Mitchell, P. S., Parkin, R. K., Kroh, E. M., Fritz, B. R., Wyman, S. K., Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E. L., & Lin, D. W. (2008). Circulating micrornas as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(30), 10513-10518. [ Links ]

Moreno Gil, S.; Celis Sosa D. F. & Aguilar Quintana, T. (2002). Análisis de la satisfacción del turista de paquetes turísticos respecto a las actividades de ocio en el destino: El caso de República Dominicana. Cuadernos de Turismo, 9, 67 -84.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). The assessment of reliability. Psychometric theory, 3(1), 248-292. [ Links ]

Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63, 33-44. [ Links ]

Ozdemir, B., Aksu, A., Ehtiyar, R., Çizel, B., Çizel, R. B., & İçigen, E. T. (2012). Relationships among tourist profile, satisfaction and destination loyalty: Examining empirical evidences in Antalya region of Turkey. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 21(5), 506- 540.

Reisinger, Y., & Turner, L. (1999). Structural equation modelling with Lisrel: application in tourism. Tourism Management, 20(1), 71-88. [ Links ]

Roberts, s. y Lewis-Cameron, A. (2010). Small island developing status: Signs and prospects. In Lewis-Camaron, A. (Ed.). Marketing island destinations: concepts and cases. Oxford: Elsevier, p. 1-10

Scheyvens, R., & Momsen, J. H. (2008). Tourism and poverty reduction: issues for small island states. Tourism Geographies, 10(1), 22-41. [ Links ]

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (1996). A guide to structural equations modelling. Erl-Baum: Hillsdale. [ Links ]

Smith, T., & Spencer, A. J. (2011). Predictors of value for money in Jamaican all-inclusive hotels. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(4), 93-102. [ Links ]

Sullivan, P., Bonn, M. A., Bhardwaj, V., & DuPont, A. (2012). Mexican national cross-border shopping: Exploration of retail tourism. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19(6), 596-604. [ Links ]

Turner, F. J. (2008). The significance of the frontier in American history. London: Penguin UK. [ Links ]

Twining-Ward, L. (2010). Cape Verde transformation: tourism as a driver of growth. Washington: The World Bank. [ Links ]

Twining-Ward, L. (2010). Sub Saharan Africa Tourism Industry Research, Phase II Tour Operator Study. Unpublished Report for the AFTFP, World Bank, Washington, DC, study conducted for AFTFP’s Competitiveness Flagship Report.

Wong, C. K. S., & Kwong, W. Y. Y. (2004). Outbound tourists’ selection criteria for choosing all-inclusive package tours. Tourism Management, 25(5), 581-592.

Yang-Wallentin, F., Jöreskog, K. G., & Luo, H. (2010). Confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables with miss specified models. Structural Equation Modelling, 17(3), 392-423. [ Links ]

Yoon, Y. S., Lee, J. S., & Lee, C. K. (2010). Measuring festival quality and value affecting visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty using a structural approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(2), 335- 342.

Zhang, H., & Lei, S. L. (2012). A structural model of residents’ intention to participate in ecotourism: The case of a wetland community. Tourism Management, 33(4), 916-925.

Received: 28 November 2016

Revisions required: 30 May 2017

Accepted: 12 July 2017