Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.13 no.4 Faro dez. 2017

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Place branding in tourism: a review of theoretical approaches and management practices

La marca-lugar en el turismo: una revisión de los enfoques teóricos y prácticas gerenciales

Marta Almeyda-Ibáñez*, Babu P. George**

*Universidad del Sagrado Corazón, Facultad Administración de Empresas, San Juan, Puerto Rico, marta.almeyda@sagrado.edu

**Fort Hays State University, Department of Management, USA, bpgeorge@fhsu.edu

ABSTRACT

This paper draws from the generic literature on branding to develop the idea of tourist based destination branding. Tourist based brand equity is proposed as an alternative to the more traditional destination resource centered idea of brand equity. In that process, it identifies various tourism related nuances that obfuscate brand building. Measurement approaches to quantify destination brand equity are compared, highlighting the pros and cons of each approach. Throughout the discussion, examples of successful destination branding practices are integrated.

Keywords: Place branding, brand equity, brand assessment, destination marketing, case studies.

RESUMEN

Este documento se basa en la literatura genérica sobre marcas para desarrollar la idea de la marca destino. La equidad de la marca basada en el turismo se propone como una alternativa a la idea más tradicional centrada en los recursos del destino de la equidad de la marca. En ese proceso, identifica diversos matices relacionados con el turismo que ofuscan la construcción de la marca. Se comparan los enfoques de medición para cuantificar el valor de la marca de destino, destacando los pros y los contras de cada enfoque. A lo largo de la discusión, se integran ejemplos de prácticas exitosas de marca de destinos.

Palabras clave: Marca destino, valor de marca, evaluación de marca, mercadeo de destinos turísticos, estudios de caso.

1. Introduction

Marketers have realized that the role of a brand goes beyond identifying the good or service to the consumers (Urde, Baumgarth, & Merrilees, 2013). The ability to create, maintain, enhance and protect brands is one of the most significant among marketer's responsibilities and is now considered as part of business strategy (Kapferer, 2012). Through the process of brand building, the firm develops the value of the brand or the brand equity. The American Marketing Association Dictionary (n.d.) defines a brand as “a name, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that identifies one seller's good or service as distinct from those of other sellers” (p. 115).

There has been an increase in the application of branding theories to the branding of tourism places. An increasing number of cities, countries, and regions have adopted marketing and branding practices during the past few decades (Gertner, 2011). There are numerous studies on the different brand elements such as brand images, brand loyalty, applied to various destinations (Jenkins, 1999; Konecnik, 2004; Lee, Lee & Lee, 2005; Matzler, Fuller & Faullant, 2007; Prayag, 2008; Scherrer & Sheridan, 2009; Tak & Wan, 2003; Watkins, Hassanien & Dale, 2006). The concept of customer-based brand equity was introduced for measuring the performance of destination branding in new studies done recently (Pike & Page, 2014).

In this paper, we will present a comprehensive literature review on tourism branding and reflect upon the historical development of branding practices in tourism. Subtopics like brand and its role (Aaker, 1991; Armstrong & Kotler, 2014;Mearns, 2007; Morgan, Pritchard & Pride, 2011; Keller & Kotler, 2012), destination branding (Cai, 2002; Eby, Molnar & Cai, 1999; Gartner, 2014; Gnoth, 1998; Khanna, 2011; Morgan, Pritchard & Pride, 2011; Olimpia, 2008; Ritchie & Ritchie, 1998; Warnaby, Bennison, Davis & Hughes, 2002), brand equity definitions (Jourdan, 2002; Keller, 1993; Kotler, 2003; Lassar, Mittal & Sharma, 1995; Leuthesser, 1988), brand equity research approaches (Aaker, 1991, 2014; Erdem & Swait, 1998; Keller, 2002, 1993, 1998, 2008), brand equity measurement (Keller, 1993, 2002; Park & Srinivasan, 1994; Koçak, Abimbola & Ozer, 2002), and customer-based brand equity for a tourism destination (Aaker, 1991, 2009Boo, 2006; Gnoth, 2002; Keller, 1993,1998, 2008, 2002; Konecnik, 2006, 2010; Konecnik & Gartner, 2007; Lassar et al., 1995; Milman & Pizam, 1995; Olimpia, Luminita & Simona, 2011; Pike & Page, 2014; Qu, Kim & Im, 2011; Zanfirdini, Tamagni & Gutauskas, 2011; Yuwo, Ford & Purwanegara, 2013) will be discussed.

2. Approaches to study brand equity

There have been many definitions of brand equity in the marketing literature. One of the earliest definitions is the one developed by a group of experts organized by the Marketing Science Institute in 1988. The experts defined brand equity as the combination of associations and behavior that led branded products to obtain increases in sales and profit margins compared to those that do not have a brand (Leuthesser, 1988). Aaker (1991) later defined it in a somewhat similar manner as, “a set of assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name, and symbol, which add or subtract from the value provided by a product or service to a firm and/or that firm's customers” (p. 15). Another frequently cited definition is the one developed by Keller (1993) who defines brand equity as “the differential effect of brand knowledge on consumer response to the marketing of the brand” (p. 2). Keller (1993) named the brand equity concept as ‘customer-based brand equity'. He explained that customer-based brand equity occurs when customers are familiar with the brand, and they have “favorable, strong and unique brand associations in memory” (Keller, 1993, p. 2).

Approaches to understand brand equity took on psychological, economic, and cultural studies perspectives. Researchers who utilize this method to study the branding effects from a cognitive psychology perspective frequently adopt associative network memory models to develop theories and hypotheses. In this approach, the brand is seen as a node in memory linked with different associations of varying strengths. One of the most cited brand equity models based on this category of cognitive psychology is the one proposed by Aaker (1991). In Keller's (2002) model, brand knowledge is a critical antecedent to brand equity, and it is theorized as a brand node in memory. An example of this is given by Keller (2008) utilizing the Apple Computers brand. He explained that if someone ask consumers about what comes to their minds when they think about Apple, there would be different associations such as creative, user friendly, among others. Other examples would be the association between Volvo brand and safety; Mercedes Benz and status (Keller, 2008).

Erdem and Swait (1998) took a more rational-economic view to decipher brand equity: when consumers are uncertain about product attributes, firms may use brands to inform consumers about product positions and to signal that their product claims are credible. In this approach, the content, clarity, and credibility of a brand are seen as a sign of the product position. These three factors may increase the perceived quality of the brand and reduce the information costs and the risk perceived by consumers (Erdem & Swait, 1998). The increase in perceived quality and the reduction in perceived risk and information costs will increase consumers expected utility, which is indeed the added value brand gives a product.

The culturally rooted brand studies utilize cultural and at times anthropological perspectives. A place is the culture that makes it a place and there is no place branding devoid of an understanding of culture(s) that make a place (Evans, 2003). Some researchers focus their work on the broader cultural meaning of brands and products. Branding is evident in the artifacts that make cultures tangible. Since the ancient times, sword blades and wine containers were etched in ways to assert their authenticity. Brands are expressions of businesses responding to a culture's aspirations. Researchers like Keller (2002) have explored topics such as brand communities, brand relationships, consumer perceptions and consumer subconscious driven by their cultural underpinnings.

3. Tourist based brand equity

A decade later after the topic of destination branding got visibility, the concept of consumer-based brand equity appeared as the most promising approach for measuring destination-branding performance (Boo, 2006; Konecnik, 2006; Konecnik & Gartner, 2007; Yuwo, Ford & Purwanegara, 2013). Konecnik (2006) published the first journal article addressing the consumer-based brand equity for a tourism destination (Pike & Page, 2014). In that article, Konecnik discussed the four components based on the Keller's (1998) generic brand equity model.

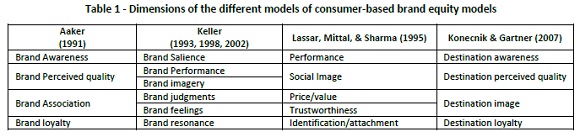

Table 1 shows the different dimensions of the different models of consumer-based brand equity (CBBE) identified in the literature and the last column indicates the assimilation of these dimensions into tourism by Konecnik & Gartner (2007).

In 2007, Konecnik published along with William Gartner another influential article, where they introduced the concept and applied it to a destination. Konecnik and Gartner (2007) proposed four brand dimensions or elements in their Consumer Based Brand Equity for Tourism Destination (CBBETD) model: awareness, image, quality and loyalty. They found that the four dimensions succeeded in the development of a brand equity measure for a tourist destination.

3.1 Destination awareness

Destination awareness or salience is at the foundation of the hierarchy. This dimension is investigated under the topic of destination selection or the travel decision process (Konecnik, 2010). Awareness represents the strength of the brand presence in the mind of the target market (Pike & Page, 2014). It is a major factor, but it is not an indicator of intent to visit (Milman & Pizam, 1995). Most models of consumer behavior state that awareness is the first step before going to trial and repeat purchase. The models agree that it is not the only step necessary before trial and repeat purchase; it is not sufficient to be aware. Consumers being aware do not guarantee that there will be interest or purchasing behavior (Konecnik, 2010). A limitation of the research done regarding this element is that it was limited to aided recall. The reason for this is the nature of the statistical technique been utilized to analyze the topic, which is mostly the structural equation modeling. Most measurements were done utilizing Likert-type scales in which a named destination is measured (Pike & Page, 2014).

3.2 Destination image

The destination image is the dimension that has attracted the most attention of researchers. Its importance led to believe that it could substitute other dimensions of the brand. Other investigators have not supported this opinion lately (Olimpia, Luminita & Simona, 2011). The overall image of a destination is influenced by the cognitive and affective evaluation of the brand. Cognitive assessment relates to beliefs and knowledge about the brand, and the affective evaluation refers to the feelings toward the brand. Unfortunately, most studies done regarding destination image focused only on the cognitive assessment. Konecnik (2010) found out that brand image is the most critical component concerning customer choice of a travel destination. Qu, Kim and Im (2011) tested a theoretical model of destination branding in which they proposed that destination image is a multi-dimensional construct influenced by the cognitive and affective images that jointly affect tourist behaviors. They included an additional construct: unique image. This additional construct is important since one of the purposes of branding is to differentiate its products from the competition (Aaker, 1991). Qu et al. (2011) results showed “destination image exerts a mediating role between the three image components as the brand associations and behavioral intentions” (p. 473). Consequently, to increase recurrent visitors and attract new tourists to the destination, tourists' destinations should establish a positive and strong brand image derived from the cognitive, unique and affective image associations (Qu et al., 2011). The researchers also found out that the overall image perceived by repeat visitors was more positive than that perceived by the first-time visitors.

This finding supports the importance attributed to this dimension by Konecnik (2010) research. That author argues that “tourism destination image plays the most important role in a destination's evaluation” (p. 38). And, the previous argument that the destination image influences in a direct manner the intentions to revisit and recommend it to others (as cited by Qu et al., 2011) is also supported. The importance of these findings is that they make clear how critical for tourism destinations is to provide favorable experiences for tourists to develop a positive image and influence their willingness to recommend the destination to others. The recommendations from tourists who have a favorable experience will help potential tourists' development of a positive image regarding the destination, and it will influence their destination choice (Qu et al., 2011). Otherwise, assessment done by Pike and Page (2014) to the research studies regarding brand image concluded that this dimension had been measured with only a few scale items. This limitation was also triggered by the utilization of the structural equation modeling. The concept of brand image is a complex one and specifically regarding destination image, there are a number of issues that complicate it further.

3.3 Destination quality

Destination quality was also found to be important because of its impact on consumer behavior (Konecnik & Gartner, 2007). In the CBBETD context, this dimension refers to how tourists perceive the quality of the environment surrounding the destination. Specifically, it relates to the quality of accommodations, food, atmosphere, and personal safety, among others. Keller (2008) identified seven dimensions of product quality: performance, features, conformation quality, reliability, durability, serviceability, style, and design. “Establishing and maintaining a quality level of a destination requires controlling all products and services ‘supplied' by the destination and this is something very difficult to realize” (Olimpia et al., 2011, p. 195). For tourists, the brand is a guarantee of quality, and they are willing to pay extra for the tranquility the brand provides them.

3.4 Destination loyalty

The last dimension of the CBBETD model is destination loyalty. This dimension deals with the intention to revisit the destination and the desire to recommend the destination to others. Konecnik and Gartner (2007) discovered that this dimension has a significant influence on the choice of a destination. It has been proven important in the consumer destination choice (Cai, 2002; Gnoth, 2002; Konecnik, 2010; Konecnik & Gartner, 2007). In their research, Qu et al., (2011) confirmed previous studies regarding the influence of the image dimension on loyalty. They demonstrated that the image had a direct influence on the intention to revisit and recommend the destination to others. Yuwo, Ford & Purwanegora (2013) stated that brand loyalty is the core of brand equity; if customers feel a bond with the brand, they will demonstrate loyalty towards that brand.

Konecnik (2010) differentiates between behavioral tourism destination loyalty and attitudinal tourism destination loyalty and how these determine brand loyalty differently. Behavioral tourism destination loyalty refers to the lifelong visitation behavior of travelers. Opperman (2000) argued that destination loyalty should be researched through a longitudinal methodology. This type of behavioral loyalty should be a much better predictor of future tourism destination choice (Konecnik, 2010). Attitudinal tourism destination loyalty refers to the tourists' attitude toward a destination. A positive attitude toward a destination influences the intention to visit and or their intention to recommend. Tourists with a positive attitude are more prone to provide a positive word of mouth. Since the importance of positive word of mouth is recognized, this is a main, influential factor when discussing tourism destination loyalty (Konecnik, 2010). Opperman (2000) stated that a composite measurement of destination loyalty would be more far-reaching, but it would not be the most practical due to the length of the study instrument. Konecnik (2010a) recognizes that her study has some limitations that must be addressed in future researches. She realizes that future studies should refine and develop the measures of the CBBETD, increase the number of variables in the awareness dimension; additional tourists' destinations investigated along with more heterogeneous tourist target groups. She also suggests that maybe there are more dimensions than the four ones already operationalized in the CBBETD model.

3.5 Brand Experience: the fifth dimension of a destination brand

Boo, Busser and Baloglu (2009) did a research study with the purpose of applying and extending the CBBETD concept to a brand measurement in an integrated model. They studied two destinations: Las Vegas and Atlantic City. Their baseline model that included the dimensions of awareness, image, quality, value, and loyalty had to be substituted for an alternative model. In the alternative model, the image and quality dimensions were combined in a new construct, brand experience. This revision was consistent with previous studies in the brand equity literature. Konecnik and Gartner (2009) had identified this problem since in previous research and had identified the possibility of brand experience unique emerging as a blend of quality and image attributes (Boo et al., 2009). Boo et al.'s (2009) main findings were: (a) brand experience (image + quality) had a positive effect on destination brand value but did not influence in a direct manner the dimension of brand loyalty (b) brand awareness affected the destination brand experience directly. Specifically, they found out that, the top of mind awareness can be a predictor of tourists' destination brand experience and that tourists who have a positive experience are not necessarily loyal.

3.6 Destination brand equity studies

Pike, Bianchi, Kerr, and Patti (2010) published a research where they measured the CBBE for Australia in an emergent market. An interesting fact is that they only test the model in one market, as opposed to the other research discussed earlier. The objectives of the study were to evaluate the CBBE model for a long-haul destination (Australia) in an emerging market (Chile) and to assess the relationship between the proposed dimensions of CBBE (brand salience or awareness, brand loyalty, brand perceived quality and brand image). To analyze the data, the researchers utilized confirmatory factor analysis, structural equation modeling, and regression. One of the main findings was that brand salience is the foundation of the model, and it is more than just awareness; it is also related to considerations for a given travel situation. Another main finding was that there were strong associations between brand salience and brand image and brand salience and perceived quality. Of the four dimensions, Australia obtained the best results in perceived quality. An interesting finding was that there were participants who had not traveled to Australia, but they had a strong positive perception of Australia's quality. The association between perceived quality and loyalty was weak. The authors suggested that CBBE should be analyzed at various points in time, to be able to track if the brand building strategies are enhancing the brand or weakening the market perceptions. Pike et al. (2010) recommend the development of a standard CBBE instrument that will facilitate the evaluation of the brand strategy effectiveness in the long run.

Zanfardini, Tamagni, and Gutauskas (2011) conducted research to assess the brand equity for two mountains tourism destination in Patagonia, a region of Argentina. The researchers utilize the Konecnik and Gartner's model. This study focused on domestic tourists; they measured consumer perceptions at the place of residence. Their findings revolved around the consumers' perceptions of both destinations since they were not assessing the relationship between the CBBETD dimensions. Despite the existence of destination specific nuances, findings indicate brand perceptions invariably impacted tourist favorability for both the destinations under study.

Yuwo, Ford, and Purwanegara (2013) applied the Konecnik and Gartner's model in their research of the CBBETD for Bandung City. The purpose of their study was to develop and test the CBBETD construct scale in the context of Bandung City, the third largest city in Indonesia and to investigate the impact of CBBETD on destination preference. They adapted the scale developed by Konecnik (2010) using qualitative and quantitative improvements. The adaptations made were regarding the image and perceived quality dimensions. The study concluded that the CBBETD model was adaptable for the Bandung City and appropriate to use in this new context.

4. Brandin practices in tourist places

While the previous discussion highlighted the benefits of developing and leveraging tourist based destination brand equity, not every destination finds value in that. Many destination management practices are informed by the resource perspective: destinations are the resources that they uniquely possess. This approach does not negate the value of tourists. It, however, starts with the supply side and it largely corresponds with what is largely called the product era in marketing (“If I have a good mousetrap, the world will beat a path to my door”). Remember that contemporary marketing theory demands that primary attention be given to customers.

Destination branding approaches started to gain visibility during the late 90's (Ritchie & Ritchie, 1998). Tourism destinations' large scale involvement in brand strategies originated in the early 90's. These strategies were foretold by cities such as New York and Glasgow, through image-building marketing activities in which they launched its slogans ‘I love New York' and ‘Glasgow's miles better' during the 1980's (Morgan et al., 2011). As anticipated by those strategies, destinations like Spain, Hong Kong, and Australia followed a strategic approach toward the development of the brand. Later, cities like Las Vegas, Seattle, and Pittsburgh also adopted the strategic approach. These responses were fueled by the need to compete more effectively, establish a decision-making framework and increase accountability to their stakeholders (Morgan et al., 2014).

Even though the destination branding concepts appeared to be a new development (Gnoth, 1998), the topic had been developed previously by researchers under the subject of destination image studies (Ritchie & Ritchie, 1998). Ritchie & Ritchie (1998) defined destination branding as “a name, symbol, logo, word mark or other graphic that both identifies and differentiates the destination: furthermore, it conveys the promise of a memorable travel experience that is uniquely associated with the destination: it also serves to consolidate and reinforce the recollection of pleasurable memories of the destination experience” (p.18). This definition incorporated some additional elements related to the concept of ‘experience' due to its importance in tourism theory and management. The first part of the definition deals with the traditional role of identification and differentiation of a brand. The second part stresses the importance of the destination brand conveying explicitly or implicitly, the promise of a memorable experience and if it is possible to a unique experience not available at any other destination (Ritchie & Ritchie, 1998).

Blain, Levy, and Ritchie (2005) revised the definition of destination branding based on a survey done by destination marketing organizations (DMO's). They enhanced the branding definition given by Ritchie and Ritchie (1998) and presented DMO's executives with the new definition. The revised definition had a more holistic approach including themes like identification, differentiation, experience, expectations, image, consolidation, and reinforcement. DMO's executives added some additional themes they understood were important to be included in the definition: recognition, consistency, brand messages and emotional responses. Based on this finding, Blain et al. (2005) proposed the following definition:

Destination branding is the set of marketing activities that (1) support the creation of a name, symbol, logo, word mark or other graphic that readily identifies and differentiates a destination: that (2) consistently convey the expectation of a memorable travel experience that is uniquely associated with the destination: that (3) serve to consolidate and reinforce the emotional connection between the visitor and the destination; and that (4) reduce consumer search costs and perceived risk. Collectively, these activities serve to create a destination image that positively influences consumer destination choice. (p.337)

It is important to understand the peculiarities that differentiate a destination brand from the branding of traditional products or services for it to fulfill all the themes presented in the definition. “The place product is a unique combination of building, facilities, and venues which represent a multiplicity of autonomous service businesses, both public and private” (Hankinson, 2009, p.98). This complex product offering must be marketed through partnerships. These partnerships include public and private sector organizations (Warnaby, Bennison, Davies & Hughes, 2002).

Gartner (2014) states that “destinations are places of life and change” (p. 1). For this reason, destination brands lack the brand stability that most product brands have. Several market segments consume it simultaneously; each consumer is compiling their unique product from the services on offer. Thus, destination marketers have less control over the brand experience (Hankinson, 2009). They provide different experiences to different tourists (Gartner, 2014). Destinations are not tangible products that can be returned if the consumer is not satisfied. “Destination brands, therefore, are higher risk as much of what constitutes the brand can easily be sometimes modified purposively and sometimes by natural or human-induced influences” (Gartner, 2014, p. 2). An additional differentiating factor in destinations is that they are not sold in the marketplace, and they are unique. No other destination can be used as a generic base to evaluate brand equity (Gartner, 2014).

Another differentiating factor of branding destinations is the complexity of the tourists' decisional process. Tourists are buying a bundle of goods and services that usually comes with an intrinsic uncertainty and a high price tag (Cai, 2002). Also, tourists are not able to test the destination before buying their travel package (Cai, 2002; Eby, Molnar & Cai, 1999; Gartner, 1989). The buying process requires from the buyers an extensive information search, where buyers' will develop a mental construct of how the potential destination fulfills their needs to reduce the perceived risk. This need for an extensive information search has an impact in the destination image element making it a critical stimulus in the destination choice process (Cai, 2002). In the marketing literature, most researchers focused on case studies of particular destination branding programs, however as Hankinson (2009) argued the approach to destination branding have lacked appropriate managerial solutions. He advocates the development of a destination branding theory that would help determine and evaluate the managerial practices and would serve as the basis for future research.

Many experts tried to apply the core branding theory developed by David Aaker and Kevin Keller to tourism destinations (Boo et al., 2009; Konecnik & Gartner, 2007; Pike et al., 2010). Others authors like Ritchie & Ritchie (1998) were conscious that destinations have some distinct attributes that traditional products and services did not own. At the functional level, many destination management organizations had the misconception that the development of logos and taglines was the basis for building a destination brand. The complexities of developing a destination brand are related to the development of the experiential element and the understanding of the tourists' decisional process. Managers must understand the macro-environment, precisely the economic, political and social issues of the destination along with the stakeholders' perception of the destination brand. Otherwise, managers and organization could be instead involved in a merely promotional exercise developing logos and taglines (Khanna, 2011).

5. Success stories: national, state, and city branding

Recent research points out that today it is harder to differentiate places according to what marketers categorized as ‘hard' factors such as infrastructure, the economy, accessibility, and availability of financial incentives. Many countries are obtaining excellent rating in these elements (Morgan et al., 2011). Factors categorized as ‘soft factors' such as the environment, friendliness of local people, art and culture traditions and leisure activities are the ones that are gaining importance with tourists and investors (Morgan et al., 2011).

Today most countries try to develop a destination brand. Examples of countries with their destination brands are: ‘Pure New Zealand', ‘South Africa it's possible', “Your Singapore' or ‘Incredible India'. The top four destination brands, as voted by their peers, are New Zealand, India, Spain and Australia (Morgan et al., 2011). In many cases, States/Provinces/Territories inside countries and cities inside them have also developed their unique brands. These developments further complicate the ramifications of tourism place branding.

5.1 National tourism brands: New Zealand and Spain

When referring specifically to branding a nation, the objective is to create a clear, simple idea built around emotional attributes. These emotional attributes can be symbolized verbally and visually and should be understood by different target audiences under different situations (Olimpia, 2008). Gilmore (2002) describes these emotional attributes as the spirit of the people and their shared purpose: “Part of this spirit consists of values-these are values that endure no matter what the times because they represent what the nation's citizens believe in and believe about themselves” (p. 286). Factors of the external environment such as culture, resources, economy have an influence on that spirit (Gilmore, 2002). Branding a nation should comprise the political, cultural, business and sports environments (Olimpia, 2008). Kotler and Gertner (2002) stated that countries should embarked in strategic place marketing in order to position the country in the global market. The authors argued that as in any strategic plan, it requires an understanding of the environmental forces that affect the country's positioning as well as the country's strength and weaknesses.

One success story is the New Zealand brand building strategy. The brand of 100% Pure New Zealand is calculated to be worth 13.6 billion (US dollars); it obtained the 21st brand position in the world (Morgan et al., 2011). Crucial in the re-development of the TNZ (The New Zealand brand) was the implementation of their first global marketing campaign in July 1999. The message of 100% Pure New Zealand was unique, simple and persuasive. Their objective was to develop and communicate a single, concise brand appealing to all markets; the message needed to be consistent, clear and particular as to what is unique to New Zealand. Also, it should convey the emotional benefits associated with the destination (Morgan, Pritchard & Piggott, 2002).

To be able to develop a successful brand positioning, New Zealand embarked on a series of marketing research studying one of its principal markets, United Kingdom. In their study, the authors found various interesting facts regarding how UK market segments perceived New Zealand. Specifically, they found that New Zealand was appealing to several unique market segments; backpackers/young people, well-traveled, well-off professionals, families with older children, empty nesters among others. These segments perceived New Zealand as a warmer destination, more vibrant and colorful than the UK. For them, New Zealand was friendly and welcoming; they described it as a down to earth destination, natural and unpretentious. Based on these findings, the positioning strategy was created (Morgan et al., 2002). They developed its principal campaign line ‘100% Pure New Zealand' with some derivatives and extensions such as ‘100% Pure Romance', ‘100% Pure Spirit', ‘In five days you will feel 100 %', among others. The key to the success of New Zealand new branding strategy was that the brand is the personification of the destination values, intellect, and culture (Morgan et al., 2002). The National Tourism Organization (NTO) known as TNZ achieved to communicate the real brand essence of New Zealand; that is its landscape, which is what brings the majority of their visitors.

Spain is another example of a successful destination branding, specifically of a repositioning strategy that involved a national promotional program utilizing Joan Miro's sun as a symbol of their modernization after the Franco era. This program included national and regional advertising as well as other initiatives from the private sector. At the same time, particular activities were occurring that strengthened Spain new positioning; hosting the Barcelona Olympics, rebuilding of Bilbao with the opening of the Guggenheim Museums, among others.

According to Gilmore (2002) the explanation for its success is: “Its branding efforts incorporate, absorb and embrace a wide variety of activities under one graphic identity to form and project a multi-faceted yet coherent interlocking and mutually supportive whole, Joan Miro's sun is used to unify graphically a myriad of activities, publicity events, and ads even though the different programmes are driven by both public and private sectors” (p. 282). This branding effort had, as a result, a brand that is efficient and impactful. Still today, more than a decade later Spain is still using Joan Miro's sun as their distinctive logo.

In 2014, the tourism and travel sector of Spain represented EUR161.0bn, which is equivalent to 15.2% of the gross national product and created 870,000 direct jobs (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2015). That year, Spain established a new record receiving 65 million tourists; the number of international visitors grew 7%, which represented the highest increase in 14 years (The Local, 2015). These numbers show the impact of the implemented marketing strategy on the sector.

5.2 State tourism branding: the case of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico, located in the northeastern Caribbean Sea, is a territory of the United States. Based on the Caribbean Tourism Organization statistics, Puerto Rico has experienced an increase in tourist arrivals during the first four months of 2014 of 4.9% (Caribbean Tourism Organization, 2014). However, at the same time, the market share of the first quarter of 2014 of 9.06%, gives Puerto Rico the fourth position, being the leaders the Dominican Republic with 26.36%, Cuba with 18.80% and Jamaica with 10.78%. Puerto Rico is being followed by Aruba with 4.62% and U.S. Virgin Islands with 4.12% (Caribbean Tourism Organization, 2014). With the objective of achieving an increase in Puerto Rico's market share, the government has targeted three different tourism segments: the ecotourism segment, luxury segment and sports tourism segment (Acevedo, 2012).

In the Caribbean tourism industry, the specialized segment of eco-tourism has been developed during the past decades (Henthorne, George & Miller, 2016). In Puerto Rico, significant efforts are being made by the Puerto Rico Tourism Company to develop this particular segment. Puerto Rico is the first country in the Caribbean to develop its own Green Certification Program. This certification endorses touristic facilities and activities that meet sustainable principles, natural and cultural conservation, education, community integration and local socioeconomic development (“Green Corner,” n.d.).

Another segment targeted by the government is the sports tourism, which is defined as sports used as an instrument for tourism activities (Kurtzman, 2005). The sports tourist can participate itself in the sports or can be a sports spectator. The different sports tourism activities are classified as sports events, sports attractions, sports tours, sports resort and sports cruises. The Puerto Rico Tourism Company (PRTC) has been involved in developing and sponsoring sports events such as the World Baseball Classic, and golf tournaments, along with some regional sports games such as Centrobasket, a Central America, Mexico and Caribbean basketball competition. During the past years, new resorts that are emphasizing their golf courses as their main attraction have opened, such as Royal Isabela Resort and Trump International Golf Club and Residencies. In the sports tourism tours category, scuba/diving tours have been part of the Puerto Rico's offering for a long time. New tours have been developed using the Puerto Rico cave system as their main attraction. Tourists can experience trekking, climbing and caving tours (“Adventure,”n.d.).

The last segment that the government is targeting is the luxury segment, a significant segment of the travel and tourism industry. The number of tourists who travel with the purpose of buying luxury goods and services is one of the fastest-growing segments of the tourism sector (Park, Reisinger & Noh, 2010). There are an increasing number of people who want to experience luxury, but not only on products and services; they are looking for experiences (Park et al., 2010). Luxury experiences include services like personal chefs, spas, leasing of private yachts, and private clubs among others. In the past five years, luxury travel had a growth of 48%, double the growth of other foreign travel. In 2014, there were 46 million international luxury trips, which represent a share of 4.6% (ITB Berlin, 2015). Puerto Rico has been developing luxury attractions defined as “truly world-class Luxury”.

In addition to this new approach toward targeting the new segments discussed above, there is a growing interest in developing Puerto Rico as a destination brand. A new law approved in 2013 creates a special committee in charge of developing a branding strategy for Puerto Rico. The primary task of the committee will be to build a permanent brand for the island. The reasoning behind this law is to protect the branding strategy from political changes. Variations in the political scenario have led to different branding strategies, which include new logos, new positioning, and new slogans. Kantrow (2013) argued that besides the “island of enchantment” image, none of the slogans helped in the development of a distinctive brand. If this statement is true, then the millions of dollars invested in developing the Puerto Rico destination brand have been a waste. It is important to find out how Puerto Rico is doing on the brand equity dimensions, to establish how effective have been the marketing strategies utilized by PRTC. It is crucial for the effective management of the marketing system to develop a valid performance measure (Feinberg, Kinnear & Taylor, 2013). This study will give the administrators valuable information regarding with which dimensions of the brand equity they should be more aggressive.

5.3 The city of San Antonio: an example of successful city branding

Another case study that included the components of an effective branding campaign is the city of San Antonio, Texas, USA (Day, 2011). The development of the campaign was in charge of the San Antonio Convention and Visitors Bureau (SACVB). When developing the brand campaign, SACVB tied the brand goals to the strategic destination goals and engaged the stakeholders in the process. They took into consideration not only the target market; they included businesses, government, and residents. SAVCB identified sources of local pride and identity to develop the communication strategy. The creative execution of the campaign appealed to residents and visitors (Day, 2011).

The brand identity developed permitted San Antonio to position itself in different market segments such as domestic, leisure, meetings and conventions, and international markets. The brand identity was developed based on four brand values: people, pride, passion, and promise. Each element of the marketing communication was integrated with the brand to ensure maximum impact (Day, 2011). One of the critical success factors was that SACVB was aware that destination branding was more than just a marketing communications campaign; consequently, they worked to assure that the destination aligns with the brand. To confirm the impact of the campaign, they developed a set of measures that helped them track the effectiveness of the campaign.

6. Challenges in destination branding

A diverse range of agencies and companies are partners of the destination marketers in the process of developing the brand identity. This range of organizations could include local and national government agencies, environmental groups, chambers of commerce, trade associations, among others. These agencies and organizations bring with them political pressures in their quest of reconciling their local and national interests. Consequently, this brings the challenge of achieving a balance between the development of creative advertising and public relations and managing local, regional and national politics (Morgan et al., 2002). According to Olins and Hildreth (2011) another challenge could be the constant misunderstanding of nation branding among experts and government officials due to the lack of knowledge of the former. Government officials are interested in nation branding because of the benefit of internal cohesion and economic and political developments externally but they ignore how the “nation branding takes place” (p. 57).

Paucity of funds brings another challenge, which is to work with minuscule budgets to create global brands and compete not only with other destination brands. To be able to compete in this situation, destination brands should be very smart in their budget spending (Morgan et al., 2002). These two challenges are more visible in the DMO's than in private tourism businesses. During the past years, there has been a reduction in the contribution of public funding to DMO's, hastened by the financial crisis experienced throughout the world (Fyall, 2011). This reduction will force destinations to do a reflection on their experiences, face their lack of resources and be more thorough in their mechanisms and management processes adopted to develop destinations to their maximum potential. Destinations should also try to maximize their resources to develop a “sustainable reputation in the minds of all stakeholders and their respective markets” (Fyall, 2011, p.101).

Along with the lack of resources and the influence of politics, destination branding faces the challenge of authenticity (Hornskov, 2014). Since the development of the branding theory in the late 1990's, branding has been concerned with authenticity. It has established that what sells and makes success is the brand honest, and its value for money (Hornskov, 2014). Accordingly, Gilmore (2002) stated that branding a country should be an amplification of what is already there, not a fabrication. When positioning a country, the destination marketer should never create an artificial position; its positioning should root in reality and the destination's central truth.

Destination marketers also face the measurement challenge. Measuring the effectiveness of brand-building is critical to the process (Blain et al., 2005; Ritchie & Ritchie, 1998). Blain et al. (2005) understood that reason behind the lack of measurement of the DMO's could be that they do not know what exactly to measure or how to measure it. They stated that further research needs to be done to investigate the reasons for DMO's not measuring visitors' perceptions or the success of their marketing efforts.

Hudson and Ritchie (2009) understood that there was a need for continuous monitoring and evaluation of the communication strategy. Brand managers should be open-minded and should be willing to change strategy depending on the effectiveness measures. Srivastava (2009) stated that the task of measuring the effectiveness of the brand strategy is a difficult one. One construct able to be utilized to measure its effectiveness is the brand equity. He states that brand equity has come forth as a significant strategic asset. If the company wants to maximize its performance in the long term, this asset needs monitoring and support.

7. Conclusion

Brand building is one of the most important of marketer's responsibilities; it is through the brand building process that the firm develops the value of the brand or the brand equity. Brand names represent a promise that sellers give to the buyers (Armstrong & Kotler, 2014). Honoring the implicit aspects of that promise is critical element in the company's relationship with consumers (Schallehn, Burmann, & Riley, 2014).

Throughout this paper, we have presented theoretical perspectives on branding, combined with examples of destinations developing branding strategies. The central objective of branding is to improve brand equity, which would give destinations competitive advantage over the others. Approaches based on psychology, economy, and cultural anthropology have been incorporated in the understanding of tourism destination brands, with a varied degree of success. However, despite noteworthy advancements, destination branding is still challenging. The complexity of this concept has brought a multiplicity of conceptualizations.

Building a destination brand brings many challenges to the destination marketing organizations. Branding is a complex process that involves many stakeholders and is difficult to manage and control, and pertains during many occasions with under-developed identities (Morgan et al., 2002). Destination managers not only have to deal with the peculiarities of the product itself, but they must also deal with two additional P's, named Politics and Paucity (Pride, 2001).

Branding has become a business discipline by itself due to the complex processes and theories associated to it, observes Mearns (2007). The complexities of developing a destination brand are concerned with the development of the experiential element and understanding of the tourist decisional process. Tourism branding needs specialized attention, given the nuances associated to this activity. The understanding of such characteristics permit destination marketers to develop a point of differentiation that would give their products sustainable competitive advantage. We hope that our analysis will be helpful for destination brand managers and researchers involved in the investigation of branding methods in tourism.

REFERENCES

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Aaker, D. A. (1996). Building strong brands. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Aaker, D. A. (2014). Aaker on branding. New York, NY: Morgan James Publishing Co.

Aaker, D.A. (2013). Strategic market management. (10th Ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Aaker, D.A. (2016). Brand equity vs. brand value [Blog post]. Retrieved 22 September 2016 from https://www.prophet.com/thinking/2016/09/brand-equity-vs-brand-value/ [ Links ]

Acevedo, E. Gobierno apuesta al turismo para salvar la economía. [Government bets on the tourism to save the economy]. Noticel. Retrieved 6 February 2016 from http://www.noticel.com/noticia/12848/gobierno apuesta al turismo para salvar la economía [ Links ]

Adventure [Website]. (n.d.). Retrieved 14 February 2016 from http://seepuertorico.com/en/experiences/adventure [ Links ]

Armstrong, G., & Kotler, P. (2014). Principles of marketing. (15 Ed.). New York, NY: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Blain, C., Levy, S. E., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2005). Destination branding: insights and practices from destination management organizations. Journal of Travel Research, 43, 328-338. [ Links ]

Boo, S. (2006). Multi-dimensional model of destination brands: an application of customer based brand equity. (Doctoral dissertation), Available from UMI. (UMI No 3243992). [ Links ]

Boo, S., Busser, J., & Baloglu, S. (2009). A model of customer-based brand equity and its application to multiple destinations. Tourism Management, 30, 219-231. [ Links ]

Brand. (n.d.) In American Marketing Association dictionary. Retrieved 16 February 2016 from https://www.ama.org/resources/Pages/Dictionary.aspx [ Links ]

Cai, L. A. (2002). Cooperative branding for rural destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(3), 720-742. [ Links ]

Caribbean Tourism Organization. Caribbean tourism organization latest statistics 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2016 from http://www.onecaribbean.org/statistics/latest-tourism-statistics-tables/ [ Links ]

Day, J. (2011). Branding, destination image, and positioning: San Antonio. In N. Morgan, A. Pritchard, & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination brands: Managing place reputation (3rd ed., pp. 269-288). New York, NY: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group.

Eby, D. W., Molnar, L. J., & Cai, L. A. (1999). Content preferences for in-vehicle tourist information systems: an emerging travel information source. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 6(3), 41-58. [ Links ]

Economywatch. Eco tourism industry. Retrieved 10 June 2010 from http://www.economywatch.com/world-industries/tourism/eco.html [ Links ]

Erdem, T., & Swait, J. (1998). Brand equity as a signaling phenomenon. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 7(2), 131-157. [ Links ]

Fyall, A. (2011). The partnership challenge. In N. Morgan, A. Pritchard, & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination brands: Managing place reputation (3rd ed., pp. 91-101). New York, NY: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group.

Gartner, W. C. (1989). Tourism image: attribute measurement of state tourism products using multidimensional scaling techniques. Journal of Travel Research, 28(2), 16-20. [ Links ]

Gartner, W. C. (2014). Brand equity in a tourism destination. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 10(2), 108-116. [ Links ]

Gertner, D. (2011). Unfolding and configuring two decades of research and publications on place marketing and place branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 7(2), 91-106. [ Links ]

Gilmore, F. (2002). A country--can it be repositioned? Spain--the success story of country branding. Journal of Brand Management, 9(4/5), 281-293. [ Links ]

Gnoth, J. R. B. (2002). Leveraging export brands through a tourism destination brand. Brand Management, 9(4), 262-280. [ Links ]

Gnoth, J.R. B. (1998). Branding tourism destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 25, 758-759. [ Links ]

Hankinson, G. (2009). Managing destination brands: establishing a theoretical foundation. Journal of Marketing Management, 25(1-2), 97-115. [ Links ]

Henthorne, T. L., George, B. P., & Miller, M. M. (2016). Unique selling propositions and destination branding: A longitudinal perspective on the Caribbean tourism in transition. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 64(3), 261-275. [ Links ]

Hornskov, S.B. (2014). The authenticity challenge. In N. Morgan, A. Pritchard & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination brands: Managing place reputation (3rd ed., pp. 105-116). New York, NY: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group.

Hudson, S., & Ritchie, J. B. (2009). Branding a memorable destination experience. The case of "Brand Canada". International Journal of Tourism Research 11, 217-228. [ Links ]

ITB Berlin. Strong growth for luxury travel. [Press Release]. Retrieved 13 September 2016 from http://www.itb berlin.com/en/Press/PressReleases/News_10245.html [ Links ]

Jenkins, O. H. (1999). Understanding and measuring tourist destination images. International Journal of Tourism Research, 1(1), 1-15. [ Links ]

Jourdan, P. (2002). Measuring brand equity: Proposal for conceptual and methodological improvements. Advances in Consumer Research, 29, 290-297. [ Links ]

Kantrow, M. R. ‘Marca pais' law creates team to conceive id for Puerto Rico. News is my Business. Retrieved 15 June 2016 from http://www.newsismybusiness.com/ [ Links ]

Kapferer, J. N. (2012). The new strategic brand management: Advanced insights and strategic thinking. Kogan page publishers. [ Links ]

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1-22. [ Links ]

Keller, K. L. (2002). Branding and brand equity. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute. [ Links ]

Keller, K. L. (2008). Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing brand equity. (3rd Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Keller, K. L., & Kotler, P. (2012). Marketing management. New York, NY: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Khanna, M. (2011). Destination branding: Tracking brand India. Synergy, IX(1), 40-49. [ Links ]

Koçak, A., Abimbola, T., & Özer, A. (2007). Consumer brand equity in a cross-cultural replication: An evaluation of a scale. Journal of Marketing Management, 23(1-2), 157-173. [ Links ]

Konecnik, M. (2004). Evaluating Slovenia's image as a tourism destination: A self-analysis process towards building a destination brand. Journal of Brand Management, 11(4), 307-316. [ Links ]

Konecnik, M. (2010). Extending the tourism destination image concept into customer- based brand equity for a tourism destination. Ekonomska istrazivanja, 23(3), 24-42. [ Links ]

Konecnik, M., & Gartner, W. C. (2007). Customer-based brand equity for a destination. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(2), 400-421. [ Links ]

Kotler, P. & Gertner, D. (2011). A place marketing and place branding perspective revisited. In N. Morgan, A. Pritchard & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination brands: Managing place reputation (3rd ed., pp. 33-53). New York, NY: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group.

Kotler, P. (2003). Marketing management. (11th Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kurtzman, J. (2005). Sports tourism categories. Journal of Sports Tourism, 10(1), 15-20. [ Links ]

Lassar, W. C., Mittal, B., & Sharma, A. (1995). Measuring customer-based brand equity. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(4), 11-19. [ Links ]

Lee, C., Lee, Y., & Lee, B. (2005). Korea's destination image formed by 2002 World Cup. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 839-858. [ Links ]

Leuthesser, L. A. (1988). Defining, measuring and managing brand equity: A conference summary. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute, Report No 88-104.

Matzler, K., Füller, J., & Faullant, R. (2007). Customer satisfaction and loyalty to alpine ski resorts: The moderating effect of lifestyle, spending, and customers' skiing skills. International Journal of Tourism Research, 9(6), 409-421. [ Links ]

Mearns, W. C. (2007). The importance of being branded. University of Auckland Business Review, 56-60. [ Links ]

Milman, A., & Pizam, A. (1995). The role of awareness and familiarity with a destination: The Central Florida case. Journal of travel research, 33(3), 21-27. [ Links ]

Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Piggott, R. (2002). New Zealand, 100% pure. The creation of a powerful niche destination brand. Brand Management, 9(4-5), 335-354. [ Links ]

Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Pride, R. (2011). Tourism places, brands, and reputation management. In N. Morgan, A. Pritchard & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination brands: Managing place reputation (3rd ed., pp. 3-19). New York, NY: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group.

Olimpia, B. (2008). Variables of the image of tourist destination. Annals of the University of Oradea, 17(2), 559-564. [ Links ]

Olimpia, B., Luminita, P., & Simona, S. (2011). The brand equity of touristic destinations-the meaning of value. Annals of the University of Oradea, 193-199. [ Links ]

Olins, W. & Hildreth, J. (2011). Nation branding: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. In N. Morgan, A. Pritchard & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination brands: Managing place reputation (3rd ed., pp. 55-68). New York, NY: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group.

Park, K., Reisinger, I., & Noh, E. (2010). Luxury shopping in tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12, 164-178. [ Links ]

Pike, S., & Page, S. J. (2014). Destination marketing organizations and destination marketing: A narrative of the literature. Tourism Management, 41, 202-227. [ Links ]

Pike, S., Bianchi, C., Kerr, G., & Patti, C. (2010). Consumer-based brand equity for Australia as a long haul destination in an emerging market. International Marketing Review. 27(4), 434- 449. [ Links ]

Prayag, G. (2008). Image, satisfaction and loyalty - the case of Cape Town. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Research, 19(2), 205-222 [ Links ]

Puerto Rico Planning Board, (2013). Selected tourism statistics. Retrieved 22 June 2016 from http://www.jp.gobierno.pr/ [ Links ]

Qu, H., Kim, L. H., & Im, H. H. (2011). A model of destination branding: integrating the concepts of branding and destination image. Tourism Management, 32, 465-476. [ Links ]

Ritchie, J. R. B., & Ritchie, R. J. B. (1998, September). The branding of tourism destination: Past achievements and future challenges. Presentation delivered at Annual Congress of the International Association of Scientific experts in tourism. [ Links ]

Scherrer, P., Alonso, A., & Sheridan, L. (2009). Expanding the destination image: Wine tourism in the Canary Islands. International Journal of Tourism Research, 11(5), 451-463. [ Links ]

Srivastava, R. K. (2009). Measuring brand strategy: can brand equity and brand score be a tool to measure the effectiveness of strategy? Journal of Strategic Marketing, 17(6), 487-497. [ Links ]

Tak, K. H., & Wan, T. W. D. (2003). Singapore's image as a tourist destination. International Journal of Tourism Research, 5(4), 305-313. [ Links ] Doi:10.1002/jtr.437

The Local. (2015). Spain greets 64.9 million tourists in 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2016 from http://www.thelocal.es/20150122/tourism-record-visitors-to-spain-top-65-million [ Links ]

Urde, M., Baumgarth, C., & Merrilees, B. (2013). Brand orientation and market orientation—From alternatives to synergy. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 13-20. [ Links ]

Warnaby, G., Bennison, D., Davies, B. J., & Hughes, H. (2002). Marketing uk towns and cities as shopping destinations. Journal of Marketing Management, 18(9-10), 877-904. [ Links ]

Watkins, S., Hassanien, A., & Dale, C. (2006). Exploring the image of the black country as a tourist destination. Place Branding, 2(4), 321-333. [ Links ] doi:10.1057/palgrave.pb.6000041

World Travel and Tourism Council (2015). Travel & tourism economic impact 2015 Spain. Retrieved 16 June 2016 from https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic%20impact%20research/countries%202015/spain2015.pdf [ Links ]

Yuwo, H., Ford, J. B., & Purwanegara, M. S. (2013). Customer-based brand equity for a tourism destination (CBBETD): The specific case of Bandung City, Indonesia. Organizations and markets in Emerging Economies, 4(1), 8-22. [ Links ]

Zanfardini, M., Tamagni, L. and Gutauskas, A. (2011). Costumer-based brand equity for Tourism destinations in Patagonia. Catalan Journal of Communication and Cultural Studies, 3(2), 253-271. [ Links ]

Received: 21 January 2017

Revisions required: 22 February 2017

Accepted: 03 April 2017