Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies no.7 Faro dez. 2011

Soft Skills as Key Competencies in Hospitality Higher Education: Matching Demand and Supply

As soft skills como competências chave no ensino superior de gestão hoteleira: alinhar a oferta e a procura

Daniela Wilks1 and Kevin Hemsworth2

1Associate Professor at University Portucalense, Department of Management Sciences damflask@upt.pt

2Coordinator of the Hospitality Management Course at Universidade Portucalense, Department of Management Sciences kh@upt.pt

ABSTRACT

This study seeks to identify the competencies perceived as essential for hospitality industry leaders. Additionally, it offers some reflections upon hospitality management higher education and examines the structure of Portuguese undergraduate degrees in order to discuss whether the current educational offer matches specific industry demand.

Both the literature review and the results of a survey with a sample of hoteliers indicate that soft skills are consistently rated as being the most important to effective performance in the field. On the other hand, an assessment of the undergraduate hospitality management programmes currently on offer in Portugal show a deficit in this area. Some recommendations are presented to redress the evident discrepancies between educational programme content and perceived industry needs. In particular the study proposes the adoption and tutelage of student by industry managers, here referred to as ";adopting a student".

KEYWORDS: Competencies, Hospitality Industry, Hospitality Management Higher Education, Soft Skills.

RESUMO

Este estudo busca identificar as competências consideradas como essências para os gestores da indústria hoteleira. Além disto, oferece algumas reflexões sobre o ensino superior de gestão hoteleira e examina a estrutura dos cursos de primeiro ciclo do ensino superior em Portugal com o propósito de analisar se a oferta educativa corresponde às necessidades específicas do sector.

Tanto a revisão de literatura como os resultados de um inquérito a uma amostra de gestores hoteleiros indicam que as soft skills são apontadas como sendo essenciais para um desempenho adequado no sector da hotelaria. Por outro lado, um exame do conteúdo dos cursos revela um défice nesta área. Algumas recomendações são apresentadas para melhor adequar o conteúdo dos programas educativos às necessidades da indústria hoteleira. Em particular o estudo propõe a adopção e tutela de alunos por gestores hoteleiros, o que é designado como "adoptar um aluno".

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Competências, Hospitalidade, Ensino Superior de Gestão Hoteleira, Soft Skills.

1. INTRODUCTION

Europe is one of the major tourism destinations and it is expected to keep that position over at least the next decade (UNWTO, 2008). In Portugal, tourism and hospitality constitute a leading economic sector and there is an increasing need for professionals equipped with the necessary competencies to guarantee quality of services. Hospitality covers a diverse range of organizations and is a highly competitive sector. Broadly speaking, the term "hospitality" refers to a large group of industries, and comprises a wide and diverse range of service operations. The expansion of the sector and increasing levels of complexity has led to a demand for highly skilled human resources across all categories, and particularly at management level. This in turn has led to a growth in number of higher educational programmes worldwide that attempt to respond to this need (Weber & Ladkin, 2008). Portugal is no exception. As Christon (2002) points out, education has a duty to provide the industry with graduates equipped with the relevant management competencies. In order to respond adequately to industry needs it is crucial that hospitality education is attuned to these needs. This is now duly recognised and there is general agreement that hospitality course curricula should be based on a clear understanding of the industry and meet employer expectations concerning the competencies that graduates ought to have acquired on completion of a degree programme (see e.g., Sigala & Baum, 2003). To this end, research has been carried out on the subject in several countries. However, to our knowledge, this subject has as yet received insufficient attention in Portugal. This article aims at filling this gap. Thus, the purpose of this study is to identify the core competencies perceived as essential for hospitality managers to adequately equip them for performance in the sector. Additionally, it offers some reflections upon hospitality management higher education and examines the course content and structure of Portuguese undergraduate degrees in order to discuss whether the current educational offer matches the demand. It begins by a review of the literature in order to identify core competencies necessary to adequate performance in the hospitality sector. This is followed by some reflections upon hospitality management higher education and an overview of the undergraduate hospitality management programmes currently on offer in Portugal. Results of a survey completed by Portuguese hoteliers on the competencies deemed essential to operate in the field will then be analysed, which is followed by a discussion of the match between educational programmes and industry needs. Finally, some recommendations are presented.

2. CORE COMPETENCIES FOR HOTEL MANAGEMENT: AN OVERVIEW

We begin by briefly examining the terms in use and then go on to review the literature on competencies perceived as relevant for the hospitality industry. The current European educational paradigm emphasises the competency–based approach to education. Weight is increasingly being placed on the acquisition of employment competencies and accordingly takes into account professional profiles and competencies, which should in turn guide the pedagogical selection of appropriate knowledge (Tuning Educational Structures in Europe, 2002). There are different definitions of competency depending on focus. Broadly speaking, they are acquired by using knowledge in practice, such as competency in problem-solving or in interpersonal communication, and are increasingly defined in terms of attitudes. As Roberts (quoted by Redman & Wilkinson, 2006: 67) puts it, competencies are "all-work-related personal attributes, knowledge, experience, skills and values that a person draws on to perform their work well". They can be further defined as hard or soft, according to whether they cover knowledge and technical skills or interpersonal aspects. No consensus has been reached in defining the concept of hospitality (see e.g. Ottenbacher, Harrington & Parsa, 2009). As previously noticed, a variety of interdependent activities have thus been included under the umbrella of hospitality that combine F&B, lodging and entertainment. Moreover, the industry covers diverse types of organisation (small, large, private, public) including hotels, casinos, resorts, restaurants, pubs, and the welfare sector among others. As industry segments, each type is unique in its nature yet shares common features and a common mission in serving the guest (see e.g.,Wood & Brotherton, 2008). This implies a variety of managerial competencies considered requisite. The precise mix is in itself difficult to determine since it necessarily covers a wide range of areas, and is generic in nature. There is an extensive literature analysing the hospitality industry and education, and studies in general highlight the fact that hospitality graduates need a range of competencies for adequate performance. Nevertheless, not much is known about the competencies actually required in hospitality work and that are unique to the sector (Baum, 2006).

Traditionally, work in hospitality has been characterised as "low skilled" in both the academic literature and the popular press (Baum, 2006), and competencies deployed in the hospitality industry thought of as purely vocational. However, this idea has now been challenged, and competencies in hospitality services are no longer seen only in terms of the technical attributes of work. Other dimensions, such as emotional, aesthetic and "experience skills" have been added, forming what Baum calls "the bundling of hospitality skills". Literature on the industry has suggested that the emphasis has changed. Concern with the core competencies deemed essential go back to the beginning of 1990s. Tas (in Roy, 2009) identified thirty-six competencies which were narrowed to five core competencies, namely self-management, communication, interpersonal relations, leadership and critical thinking. Since then many other studies have been conducted. Rudolph (1999) investigated the most desirable outcomes for hospitality education, and concluded that the highest rated competencies were in the areas of communication. According to his findings, education should include excellent reading skills, sensitivity to and appreciation for other cultures (considered core), good coaching skills, economics and stress management, team building and coping with change. As for quantitative analysis, the key abilities were to plan and prioritise, followed by financial analysis (thinking and reasoning aptitudes). Computer literacy and proficiency with software were considered the most important competencies, while "hands-on’ proficiencies such as foodservice (cooking) were rated as less important. Students should also demonstrate ethical standards and strong values. Research in the UK and US has found generic interpersonal and human relations competencies to be very important, while technical competencies were seen as less important (Raybould & Wilkins, 2006). On the same lines, Australian hospitality managers identified the generic domains of interpersonal relations, problem-solving and self-management as the most important while the ten most important descriptors included dealing effectively with customer problems and maintaining professional and ethical standards (Raybould & Wilkins, 2006). Staton – Reynolds (2009) reviewed the competencies considered important for success in entry level managers by hospitality recruiters and university educators and found that both groups recognised emotional intelligence as being essential. In a world increasingly based on Information Technology capabilities, these, coupled with communication competencies, are for some researchers (e.g., Cho, Schmeizer, & McMahon, 2002), the most important competencies to be acquired by hospitality students. However, Fournier & Ineson (2009) found that IT competency was the least regarded. The competencies identified as essential by Kay & Russette (2000) include recognizing customer problems, showing enthusiasm, maintaining professional and ethical standards, cultivating a climate of trust, and adapting creatively to change. Other researchers emphasise the ability to cope with emotional demands (e.g., Johanson & Woods, 2008), to empathise with customers, possess emotional intelligence (Baum, 2006), show leadership, and develop competencies associated with interpersonal, problem-solving, and self-management skills (Raybould & Wilkins, 2006). Since hospitality is almost by definition an international industry, cross-cultural competencies have been identified as fundamental. Beer (2009) conducted research into the concept of global competency within the curriculum of hospitality management programmes and concluded that effective communication in another language, cross-cultural sensitivity and adaptability are some of the most important competencies. It is worthwhile to refer to Chung-Herrera, & Lankau (2003), who developed a competency model based on two dimensions: self-management (comprising ethics, time management, flexibility, adaptability and the like) and strategic positioning (comprising awareness of customer needs, commitment to quality, concern for the community). Finally, it is of some significance that in a keynote address to a recent conference, Pizam (2011) stressed the crucial importance of soft skills in the hospitality industry. For him, hospitality students should be educated in good manners, civility, and proper speech, in addition to technical and conceptual skills and hospitality competence.

From the above, it may be concluded that a paradigm shift has occurred in terms of the competencies required for hospitality management, and the emphasis now is on personal qualities and soft competencies, whereas vocational/technical competencies are viewed as comparatively less important. We shall turn now to hospitality education.

3. HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT HIGHER EDUCATION

Hospitality management is just one segment of the hospitality industry but occupies its own niche (Barrows, 1999). Although hospitality is one of the oldest professions, it has a comparatively short life in higher education. Hospitality higher education in general is a specialised area of study that aims at preparing students for careers in the hospitality industry. As such, it seeks to bring together vocational training and academic education, developing from early European apprenticeship programmes and beginning to take root in universities in the early 1900s in the USA and rather later in Europe (see e.g., Barrows & Johan, 2008). Hospitality management higher education has faced some difficulties in establishing itself as an academic field within academia. It has been pointed out (e.g., Borrows & Johan, 2008) that one of these difficulties is due to the tendency for hospitality management educators to argue that the field should be kept distinct due to its "uniqueness" as opposed to other fields of management. Consequently, it occupies an uncomfortable position in academia. Furthermore, has failed to deliver research which has now become a compulsory criterion for success in academic terms. Hospitality management has many of the features common to other forms of management, but also unique attributes that require technical-vocational instruction. It should also be noted that students attracted to the subject actually expect to get this vocational training (Raybould & Wilkins, 2006). Knowledge about hospitality has been drawn from the industry and this was reflected in the curriculum; only in the late 1990s was it liberated from its vocational base and extended to a broader scope (Morrison & O´Mahony, 2003). Courses on other subjects related to management, economics and other social sciences were incorporated. As noted earlier, there has lately been a paradigm shift in terms of the competencies required for hospitality management and the emphasis now is on leadership, emotional intelligence and the like.

Nevertheless, the view that hospitality education is vocational remains influential and universities have often been reluctant to grant hospitality management programmes the same status as other subjects (Rudolph, 1999). There is an ongoing debate , some calling for a need for the discipline to liberate itself from the vocational domain and establish itself as a sound social science (Lashley, 2004) and to become ,"vocational[ly] reflective"(Airey & Tribe, 2000). It may be said that hospitality management higher education is still immature when compared with more traditional fields, and has yet to establish its identity as an academic subject. In spite of being a relatively recent academic pursuit, hospitality degree programmes have proliferated rapidly due to the growth of the industry. For Breakey & Craig-Smith (2007), the trend has been to move away from subjects such as cooking and hotel operation to quality management and technological applications. According to the same source, patterns in different countries have developed in similar ways, from a limited choice of subjects to multiple options. Moreover, the universal trend is for hospitality management to be incorporated within Business Schools, while tourism tends to be taught in different departments. Courses may include management subjects and hotel and food service operations. Some programmes offer a selection of more specialised subjects such as private club or casino operation. Indeed, a growing trend is to offer a greater number of optional specializations. As noted above, in order to respond to changing industry needs, it is crucial that hospitality degree programmes have a clear understanding of the industry and employer expectations of the competencies that graduates should possess. Integrating education and practical training (and in this way increasing employability) has been a preoccupation in higher education as mentioned earlier and in the case of hospitality this is crucial. Educational institutions have a responsibility to ensure that the required competencies are mastered by students (Moncarz & Kay, 2005) though previous studies have shown that there are differences between educators and industry professionals in what constitute the important competencies (e.g., Sigala & Baum 2003). Ultimately, the goal is to match program outcomes with industry needs and simultaneously to provide a higher education without falling into the trap of "the tyranny of relevance" (Lashley, 2004). In short, higher education institutions are called on to provide vocational training, management knowledge as well as general academic education and they may be unprepared for this combination. In what follows, we will assess the current state of hospitality education in Portugal. First, we will look briefly at the vocational programmes on offer and then concentrate on degree programmes.

4. HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT HIGHER EDUCATION IN PORTUGAL

The national tourism and hospitality educational provision includes a variety of programmes. There are several vocational courses for students in possession of a basic education who aspire to work in the sector. The Portuguese Tourist Board has schools in the main cities and the Ministry of Education also offers courses for school leavers, which tend to be concentrated on vocational subjects such as cooking and waiting at table. There are also similar courses for adults and some private initiatives. Education in tourism goes back to 1957, but as noted above, while there is a long tradition of vocational training for the hospitality industry, higher education programmes in the country are quite recent. In the eighties degrees in tourism were first to appear and, one decade later, hospitality management degrees (Salgado, 2007). For the year 2011 (Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education), and within the field economics, management and accountancy, there are 18 courses under the name hospitality management or tourism management offered across the entire country. There are many more on tourism. In terms of infra-structure (faculty and facilities), the public technical schools tend to have good facilities for practical functions such as cooking and accommodation. These vocational subjects are taught in general by technically qualified staff. Following new legislation, the trend in future will be towards recruiting at PhD level, but this requirement might be difficult to fulfill for vocational subjects. It should be noted that there are to date few faculty members with professional experience and with doctoral degrees teaching in the hospitality sector, and then usually specialized in other fields such as nutrition, education among others (see Salgado, 2007). This article focuses on undergraduate programmes in hospitality management offered at Portuguese higher educational institutions. For research purposes, we defined such programmes according to whether the formal degree designation included either of the following terms: hospitality and hotel management (see Salgado, 2007). Programme comparables were based on information provided by the relevant institutional web sites. Both private and public higher education institutions were included.

Programme curricula do not vary much by institution. There are common goals and components across the curriculum, a combination of management, other general subjects, and vocational subjects. The following were core subjects in all degrees: IT, accountancy (general and financial), human resources management, marketing, law, and foreign languages. The overall number of subjects in each area depends on the school. Some institutions stress the practical/technical aspects, others include five semesters of English plus three or four of a second foreign language. In general there are no special requirements for admission. Vocationally-biased subjects comprise F&B and accommodation, hygiene and food security, gastronomy and wines. The programmes tend to include a period of internship or work placement varying from institution to institution (from two months twice during the course to one semester). Only one offers options in the field of leadership and communication.

5. EMPIRICAL STUDY 5.1. SURVEY INSTRUMENT AND DATA COLLECTION

In order to identify the competencies perceived as essential for Portuguese hotel managers, a survey instrument was constructed. A list of competencies was built based on Fournier & Ineson (2009) and Redman & Wilkinson (2006), to which an open-ended question was added inviting participants to include any other competency and skill not included in the list. This list was first presented as a pre-test to 16 hotel managers who were attending an in-service training course for hotel directors, and after analysing the findings, 55 competencies were then randomly mixed. The following year, a final list of competencies was passed to another group attending the same course (71% of the sample), the remainder being approached by personal contact on the part of one of the authors. The total sample comprised 50 participants. It was a convenient sample and all were volunteers. They were asked to rate each competency and skill according to its relevance to effective performance in the field. The areas included traits such as adaptability, ability to work in a team, interpersonal competencies, communication, leadership and the like; technical/vocational competencies such as knowledge of F&B, accommodation management, knowledge of HACCP, cooking competencies, property development; scientific and other knowledge such as law, IT, marketing, human resources management, quality management, statistics, etc. Respondents were asked to rate the importance of the competencies on a 5 point Likert scale ranging from critically important (=5) to not very important (=1). To the list of competencies deemed to be key competencies in the field of hospitality industry were added questions on demographic data and information concerning the employing hotel.

5.2. FINDINGS

Characteristics of the participants indicated that 63% were males, the mean age was 40 years old (SD=9.34) and 90% were hotel directors. As for work experience, 69% of them had about 7 years' tenure (M=6.77, SD=6.56), 64% worked for chain operators, 88% of them in 4-star units. The large majority were working in the north of the country (80%).

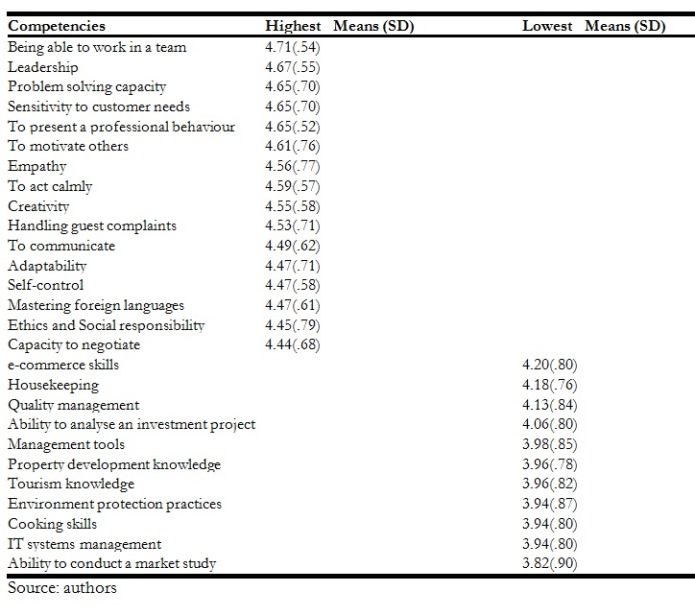

Following previous research (Fournier & Ineson, 2009), mean values of 4.50 or above were considered "critical competencies", those between 3.50 and 4.49 denoted "of considerable importance", while values between 2.50 and 3.49 signified "moderately important". Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations for the highest and lowest rated competencies. The highest mean value was for "being able to work in a team" followed by "leadership", and the lowest values were for "to know how to conduct a market study". The ten competencies rated as critical were either traits or interpersonal competencies ("soft competencies") and related to customer handling. All the others were of considerable importance and also in this group the highest mean value is for competencies related either to personality traits or interpersonal competencies with the exception of mastering

Table 1: The highest and lowest rated competencies

6. DISCUSSION, RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSION

As in previous research in other countries, the findings suggest that hospitality employers tend to see personal qualities and interpersonal competencies as very relevant for the field, while technical competencies are seen generally as somehow less important. It should be noted that in surveys of employers in general, personal qualities and competencies such as customer handling, communication, discipline, punctuality work ethic have been considered as most highly valued (Redman & Wilkinson, 2006). Both the literature review and the findings of results of a survey show that hospitality practitioners tend consistently to rate interpersonal competencies as being most important. On the other hand, an assessment of the undergraduate hospitality management programmes currently on offer in Portugal show a deficit in this area. These findings suggest some discrepancies between educational programme content and perceived industry needs. Admittedly, courses on offer in Portugal seem to provide a period of internship as part of the course that, while giving occasion to develop practical competencies, lack opportunity to train "soft competencies".

Overall, the implication of the above findings is that hospitality management educators should attend to those competencies perceived as essential for the field by practising professionals, and provide programmes to develop them. Since what is perceived as most important has greatly to do with personality disposition, ultimately it is important to select students who have an adequate profile. Flexibility and adaptability, for instance, are difficult to develop unless students possess certain personality traits. This is a controversial point because there is competition for students and the sector may not feel able to afford precise discrimination. It nevertheless remains an important point to be addressed. Moreover, as Redman & Wilkinson (2006) points out, focusing on some competencies can legitimise prejudice, since what is perceived as most desirable may often correspond to a demeanour associated with a white middle-class profile. In addition, these competencies tend not to be highly rewarded when unaccompanied by technical competencies. There are also risks in developing interpersonal competencies, for instance, and neglecting the acquisition of technical competencies and the knowledge essential to managing an organisation. Furthermore, higher education is not only a means of getting a job. It is about "getting an education". As Lashley (2004) points out, it is necessary to escape the tyranny of relevance and develop analytical and critical thinking essential to creating "reflective practitioners". Soft skills are best taught though role modeling rather than formal academic instruction. According to Bandura"s(1986) Social Learning Theory, people learn from one another through observation and imitation (modeling), reproducing given behaviours. The process involves close contact, imitation of seniors, understanding the concepts and role model behavior. Following this line of thought, we propose the adoption and tutelage of students by industry managers with the aim of cultivating the soft skills required to perform well in the field. "To adopt a student" would imply the shadowing of an experienced manager in his/her day to day interactions with guests and other people, in other words, a generalized induction into "people skills". While a conventional internship usually entails performing specific tasks such as front office, the latter would imply observation and imitation of soft skills such as professional manner, communication and leadership skills.

A balance must be struck between applied and theoretical approaches, between technical competencies and an academic curriculum in addition to developing a complex of competencies relevant for service work. In this resides a potential point of tension involving the question of proportionate mix. Arriving at an optimal programme requires a coalescence of expertise entailing contributions from non-academics with relevant industrial experience on the one hand, and on the other, from academics having the theoretical specialties requisite to a higher education. As the field of hospitality industry continues to expand and change, so also does the role of its managers. The speed at which changes take place and the unpredictable direction of such changes suggests that, rather than concentrating on a narrowly conceived specific approach, it would be better to focus on generic competencies and broad learning outcomes that are both transferable and more easily updated, as has been proposed (e.g., Raybould & Wilkins, 2006). In other words, the discipline has to go beyond practice and become more "reflective" (Airey & Tribe, 2000). Furthermore, education programmes ought to be continuously checked and adjusted to meet the demand.

This study contributes to the existing literature on hospitality management higher education in three ways. By identifying the competencies deemed to be important for the industry, it will assist educators; by analysing what schools deliver, it will help promote a curricula more attuned to professional needs; by investigating a sample of Portuguese hotel managers and comparing findings with other samples, it extends previous research. Although it was intended to have a representative sample of hotel managers, this was not achieved, and future studies should include a more representative sample. Future research should also examine the views of educators and students, perhaps making use of qualitative research to obtain different insights. Rapid changes in the hospitality industry will demand constant research updating.

Three main conclusions stand out from this study. Firstly, that priority should be given to "soft competencies"; secondly, that educating students to manage hospitality units represents a formidable challenge. On one hand, they need to acquire knowledge of economics, management and of other sciences in addition to vocational subjects; on the other hand, they need a set of competencies to perform well, all of which must be achieved in a span of three years in close cooperation with the industry. Thirdly, it may be concluded that hospitality management, although in the past a vocational subject, is increasingly becoming an academic subject on its own right. As such, it is multidisciplinary in nature, covering several fields each with its own vernacular. To build a common language will require time, but will assuredly represent an intellectually exciting endeavour.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

AIREY, D., & TRIBE, J. (2000), "Education for Hospitality", in Lashley, C., & Morrison, A., (Ed.) In Search of Hospitality: Theoretical Perspectives and Debates, Butterworth, Oxford, 276-292. [ Links ]

BANDURA, A. (1986), Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Learning Theory, General Learning Press, New York. [ Links ]

BARROWS, C. W. (1999), "Introduction to Hospitality Education", in Barrows, C. W., & Bosselman, R. H., (Eds) Hospitality Management Education, Binghamton, Haworth Hospitality Press, New York, 1-17. [ Links ]

BARROWS, C. W., & JOHAN, N. (2008), "Hospitality Management Education", in: Wood, R. C., & Brotherton, B., (Ed.) The Sage Handbook of Hospitality Management, Sage Publications Ltd., London, 146-162. [ Links ]

BAUM, T. (2006), "Reflections on the Nature of Skills in the Experience Economy: Challenging Traditional Skills Models in Hospitality", Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 13(2), 124-135. [ Links ]

BEER, D. J. (2009), "Global Competency in Hospitality Management Programs: A Perfect Recipe for Community Colleges", unpublished doctoral dissertation, Louis University, Illinois, Chicago. [ Links ]

BREAKEY, M. N., & CRAIG-SMITH, S. J. (2007), "Hospitality Degree Programs in Australia: A Continuing Evolution", Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 14 (2), 102-118. [ Links ]

CHRISTOU, E. (2002), "Revisiting Competencies for Hospitality Management: Contemporary Views of Stakeholders", Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Education, 14 (1), 25-32. [ Links ] CHO, W., SCHMEIZER, C. D., & MCMAHON, P. S. (2002), "Preparing Hospitality Managers for the 21st Century: The Merging of Just-in-time Education, Critical Thinking, and Collaborative Learning", Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 26 (1), 23-37. [ Links ] CHUNG-HERRERA, B. G., ENZ, C. A., & LANKAU, M. (2003), "Grooming Future Hospitality Leaders: A Competency Model", Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 44 (3), 17-25. [ Links ]

FOURNIER, H., & INESON, E. (2009), "Closing the Gap Between Education and Industry: Skills and Competencies for Food Service Internships in Switzerland Hospitality & Industry Management", Paper presented at the International CHRIE- Conference, referee Track at http://scholarworks.umass.edu/sessions/wednesday/11retrieved in 2010). [ Links ]

GREEN, J. L. (2007), "The Essential Competencies in Hospitality and Tourism Management: Perceptions of Industry Leaders and University Faculty", unpublished doctoral dissertation, New Mexico State University, ProQuest dissertations and thesis (UMI No 3296128). [ Links ]

JOHANSON, M. M., & WOODS, R. H. (2008), "Recognizing the Emotional Element in Service Excellence", Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 49 (3), 310-316. [ Links ]

KAY, C., & RUSSETTE, J. (2000), "Hospitality -Management Competencies -Identifying Managers´ Essential Skills", Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 41(2), 52-63. [ Links ]

LASHLEY, C. (2004), "Escaping the Tyranny of Relevance: Some Reflections on Hospitality Management Education", in Tribe. J., & Wickens, E., (Ed.) Critical Issues in Tourism Education, APTHE publication No14 (Proceedings of the 2004 conference of the association in higher education, Missenden), 59-70. [ Links ]

MONCARZ, E., & KAY, C. (2005), "The Formal Education and Lodging Management Success Relationship", Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Education, 17 (2), 36-45. [ Links ]

MORRISON, A. & O"MAHONY, G. B (2003), "The Liberation of Hospitality Management Education", International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 15 (1), 38 –44. [ Links ]

OTTENBACHER, M., HARRINGTON, R., & PASA, H. G. (2009), "Defining the Hospitality Discipline: A Discussion of Pedagogical and Research Implications", Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 33 (3), 663-683. [ Links ]

PIZAM, A. (2011), "The Domains of Tourism & Hospitality Management", Paper presented in the Plenary Section at the First International Conference on Tourism & Management Studies, Faro [ Links ]

PORTUGUESE MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (2011), Guia de Acesso ao Ensino Superior, http://www.acessoensinosuperior.pt/indarea.asp?area=VII&frame=1 (retrieved in February 2011). [ Links ]

RAYBOULD, M., & WILKINS, H. (2006), "Generic Skills for Hospitality Management: A Comparative Study of Management Expectations and Student Perceptions", Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 13(2), 177-188. [ Links ]

REDMAN, T., & WILKINSON, A. (2006), Contemporary Human Resource Management, FT/Prentice Hall, London. [ Links ]

ROY, J. S. (2009), "An Analysis of Business Competencies Important for Entry-level Managers in Destination Marketing Organization", unpublished doctoral dissertation, School of Business & Technology Capella University, ProQuest dissertations and thesis (UMI 3341871). [ Links ]

RUDOLPH, R. D. (1999), "Desirable Competencies of Hospitality Graduates in Year 2007", unpublished doctoral dissertation, Cornell University, ProQuest dissertations and thesis (UMO 9927393). [ Links ]

SALGADO, M. A. B. (2007), "Educação e Organização Curricular em Turismo no Ensino Superior Português", unpublished doctoral dissertation, Universidade de Aveiro. [ Links ]

SIGALA, M. & BAUM, T. (2003), "Trends and Issues in Tourism and Hospitality education: Visioning the future", Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(4), 367-376. [ Links ]

STATON-REYNOLDS, J. (2009), "A Comparison of Skills Considered Important for Success as an Entry Level Manager in the Hospitality Industry According to Industry Recruiters and University Educators", unpublished doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University, Proquest dissertations and thesis (UMI1465109). [ Links ]

TUNNING, EDUCATIONAL STRUCTURES IN EUROPE (2002), Report of the Engineering Synergy Group, http://www.tuning.unideusto.org/tuningeu/index.php?option=content&task=view&id=173 , (retrieved in January 2011). [ Links ]

UNWTO (2008), Tourism 2020 Vision, Tourism Highlights. [ Links ] WEBER, K., & LADKIN, A. (2008), "Career Advancement for Tourism and Hospitality Academics: Publish, Network,

Study, and Plan", Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 32 (4), 448-466. WOOD, R. C., & BROTHERTON, B. Eds. (2008), "The Nature and Meanings of "Hospitality", The Sage Handbook of Hospitality Management, Sage Publications Ltd., London, 37-61. [ Links ]

Submitted: 15.10.2011

Accepted: 20.11.2011