Introduction

Digital Platform Work (DPW) is characterised by a remote, digital, algorithmic-based mediation of the employer-worker relationship (Pesole et al., 2018). Digital Platforms (DPs) the enablers, operate as intermediaries, create their own markets, turn consumers into allies - which Culpepper and Thelen (2020) identify as a new form of socio-economic power - and establish networks, prioritising control over direct ownership while evading national regulations (Boyer, 2022). Rahman and Thelen (2019) refer to this as platform capitalism.

DPW varies. The definition encompasses jobs in diverse sectors (e.g., information technologies, finance, house cleaning, plumbing) and that require different skills. DPW is usually outsourced or independently contracted part-time work, tele-work, or zero-hour contracts (Huws, 2011). This management practice stems from a trend begun in the 1980s and 1990s (Huws, 2006) that blends deregulation, individualisation and flexibilisation, which accelerated after the Great Recession of 2008. In this paper, we will focus on the passenger transport service, in which Uber is the most well-known platform company that mediates the connection between workers and clients.

This sector has been chosen for study given how passenger transportation is an example of on-location DPW i.e., the worker (service provider) and the client meet in person, which in and of itself, is characterised by segmented tasks, irregular schedules, uncertain income, and no contracts (Berg et al., 2018). In Portugal and Spain, the share of DPW in the workforce is 9.1% and 14%, respectively, higher than the European Union average of 8.6% (Brancati et al., 2020), of which on-location DPW is the most relevant form in these two Iberian countries. Moreover, as the share of on-location DPW increases, the number of workers holding atypical contracts in the labour market grows and tensions rise between incumbents and DPW in the passenger transport sector. In our two case-studies, the surge of workers in individual transportation was greeted with both animosity and protests by taxi drivers, who have traditionally provided regulated passenger transportation service. In addition, workers in new market segments have little bargaining power (Brancati et al., 2019). Although governments have intervened in response to these issues, the new regulations have been diverse. Why?

The comparison of the nature of government regulations should not be underestimated as there may be many reasons behind a specific government’s action taken in a novel context. Thelen (2010) uses the institutional lens of the varieties of capitalism (Hall and Soskice, 2001) to explain the differences in regulation in Germany, Sweden and the United States, correlating regulation with the underlying market economy. Funke and Picot (2021) confirm this analysis for Germany, where platform work in the private transportation sector has not yet been regulated and may not be. However, while Portugal and Spain arguably have the same model of capitalism - the mixed-market or Mediterranean economies model (Molina and Rhodes, 2007), after the surge in passenger transportation DPW (named TVDE in Portugal and VTC in Spain) -, they regulated it differently: whereas Portugal regulated TVDEs and created a new market, Spain restricted VTC activity.

This paper analyses the content of reforms and the coalitions that supported the new legislation approved in Portugal and Spain in 2018, highlighting the role of the Portuguese and Spanish centre-left parties. In Portugal, the discussion process began in 2016. Although the centre-left (Partido Socialista - PS) Portuguese government was supported by a parliamentary agreement with the left (Partido Comunista Português - PCP and Bloco de Esquerda - BE) since the 2015 legislative election, the centre-left and centre-right (Partido Social Democrata - PSD) parties formed a coalition to approve the law that regulates the TVDE service in August 2018, and the left parties and the taxi associations opposed the legislative reform. In Spain, although the process of regulating VTCs was initiated in 2015 by the centre-right (Partido Popular - PP) government, it culminated in September 2018, when the centre-left (Partido Socialista Obrero Español - PSOE) minority government came to power in June 2018. Occurring after a motion of no confidence vote that ousted the PP government, the PSOE was supported in parliament by the left (the Unidas Podemos coalition - Podemos) and the legislation passed restricted the number of VTC licences and defined the geographic boundaries within which they could operate (much like taxis).

We argue that the two countries employed distinct strategies to address the rise in precariousness. In Portugal, the expansion of the sector was viewed as an opportunity to boost employment among those outside the core labour force. Furthermore, the law included some secondary measures to protect vulnerable workers, namely the need for a labour contract. In Spain, containing the DPW and safeguarding the traditional taxi sector was seen as the best option to tackle precariousness in the labour market. In Portugal, market expansion was seen as a positive strategy, and greater solidarity meant liberalising the sector and developing some minor mechanisms of labour protection. On the other hand, in Spain the strategy was not to expand the market but to fight against liberalisation.

As for the structure of the present paper, we begin by reviewing the key literature on the topic and explaining the main argument. The section that follows presents the methodology. The two case studies are then described and compared. The final section provides our conclusions.

1. Digital capitalism and the politics of labour market solidarity

Thelen (2018) argues that countries regulate DPW differently. In her view, the modus operandi of DPs is more compatible with Liberal Market Economies (LMEs), where firms coordinate their actions through the market, than with Coordinated Market Economies (CMEs), where firms coordinate strategically (Hall and Soskice, 2001). In CMEs, employers and workers have incentives to protect internal labour markets (Estevez-Abe et al., 2001) and create barriers to the emergence of non-institutionalised employment. Thelen (2010) argues that these incentives work best in industry, which provides stable and well remunerated jobs with a clear link between employment and social security contributions and where workers’ skills and experience are key to the production process. However, this does not hold for the service sector where temporary jobs and low pay are more frequent. Thus, DPW is likely to grow more rapidly in LMEs than in CMEs. A third variation of market economies has been studied more recently in the field of the Comparative Political Economy (CPE) literature: the Mixed-Market Economies (MMEs), where coordination is achieved through state mediation (Molina and Rhodes, 2007). Portugal and Spain are most often characterised as belonging to this ideal type, but the literature has not analysed the approach to DPW in MMEs.

The dualisation literature looks at the national level to explain the differences between insiders - employed individuals holding permanent contracts - and outsiders - unemployed individuals or workers holding non-permanent contracts. Rueda (2007) argues that social democratic governments align with unions to protect the jobs of insiders and do not promote active labour market policies to support outsiders. If this hypothesis were to be used in our analysis, centre-left parties would be expected to prioritise the interests of taxi drivers (insiders) in the two countries. This was not the case in Portugal as the centre-left legislated against their interests.

From our perspective, the CPE literature finds it difficult to explain why Portugal and Spain have regulated the passenger transport sector differently. As the divergence is not explained by the types of capitalism or dualisation literatures, it is necessary to innovate conceptually to address this puzzle.

We argue that different conceptions of solidarity, in the vein of what is proposed by Doellgast et al. (2018), were in place when political parties regulated the sector. On the one hand, Portuguese socialists saw the sector’s liberalisation as an opportunity for job creation, and some regulations concerning job contracts were introduced. This was considered positive for vulnerable workers because they were now not only able to access employment, but were legally required to receive contracts from employers. In Spain it was different. The centre-left, together with Podemos, saw the protection of the traditional taxi sector as the best solution to foster solidarity. The main objective was to limit the size of DPW and therefore impede this sector’s liberalisation. As explained in the empirical section of this paper, a centre-left (PS)/centre-right (PSD) coalition regulated the TVDE service in Portugal, which became a regulated service competing with the traditional taxi service and with fewer regulations, whereas in Spain, a centre-left (PSOE)/left (Podemos) coalition restricted the number of VTC licences and defined the boundaries within which they could operate to marginalise VTCs and preserve the traditional taxi service. Portugal and Spain thus embraced distinct logics of solidarity because the strategy developed to fight labour market inequalities was radically different. Market expansion versus market containment was at the core of this divergence.

2. Methodology

This paper compares the way Portugal and Spain regulated the activity of individual and remunerated transportation of passengers in uncharacterised vehicles connected to a DP. Despite similarities between the two cases (a centre-left government, many radical left members of parliament, and a growing DPW sector before legislative changes were implemented), this comparison proves interesting because Portugal and Spain regulated this type of activity differently.

The data is drawn from three sources: (i) official documents; (ii) parliamentary debates; and (iii) media news coverage. Official documents include the laws approved (one in Portugal, with other legal dependencies, and three in Spain, with other legal dependencies), legal decisions by courts of justice, legal documents from the European Union, and institutional statements issued by different actors during the process of legislative negotiation. Parliamentary debates include the main debates on the regulation of DPW in the transport sector, as well as voting sessions (two debates and one voting session in Portugal; two parliamentary debates in Spain, one for each Royal Decree approved in 2018). Media news coverage includes the news on this subject featured in three prominent newspapers of each country - Público, Expresso and Observador in Portugal, and El Mundo, El País and ABC in Spain - during the years of 2016, 2017, and 2018.

The analysis of legal documents gives information about the regulations in place. The analysis of parliamentary debates was crucial to characterising the positions taken by different political parties and governments, while the analysis of media news was important to shed light on the positions of other actors.

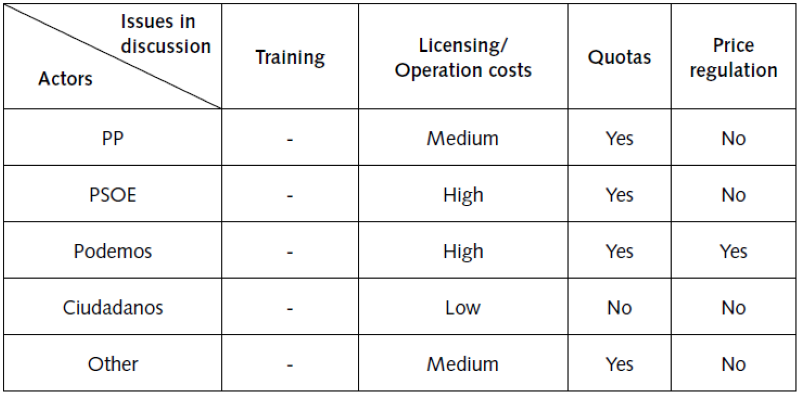

After the first analysis of the legal documents, we defined four core dimensions of contention - driver training, licensing and operation costs, quotas, and price regulation (see Table 1 in section 5) - plus the position of actors vis-à-vis other actors. We use this framework to analyse all the documents and identify and retrieve the most salient statements.

3. Portugal: Liberalising to Boost Employment and Regulating Job Contracts to Fight Precariousness

3.1. The Regulations in Place

Portuguese Law 45/2018 (Assembleia da República, 2018) regulates the activity of individual and remunerated transportation of passengers in uncharacterised vehicles by means of a DP. The law, approved in August 2018, specifies that there are three service providers: digital platforms, TVDE operators, and car drivers. Digital platforms must comply with regulations that determine the information made available and displayed to the service consumer (who is protected from service disruptions and below par provision) and they must pay a 5% tax on the intermediation margin.

The TVDE operator must be a licensed Portuguese company. The TVDE operator is responsible for managing the business - hiring the drivers, owning the vehicles, and providing the TVDE service - thus acting as an intermediary between the DPs and the drivers (Amado and Moreira, 2019).

The Portuguese law regarding the TVDE drivers specifies five aspects: drivers should be registered and certified: hold a valid driving licence, receive training, have an adequate personality, and drive a car certified by the Mobility and Transports Institute as suitable for TVDE service. Training remains valid for five years (taxi drivers are exempt from the TVDE training programme if they wish to drive a TVDE car). Drivers who are not working independently should have a written contract with the TVDE operator in compliance with Article 12 of Código do Trabalho [Portuguese Labour Code]. Working time is limited to ten hours per day, but this limit can be reduced if cumulative hours exceed the rules of the Código do Trabalho, which is also regulated by DL 237/2007 (for drivers under contract) and DL 117/2012 (for independent drivers). For drivers under contract, Article 12 of the Código do Trabalho states that a regular and just payment shall be made by the employer to the employee in compensation for the work activity.

The Portuguese TVDE law thus regulates and frames the TVDE service as a legitimate competitor to the traditional taxi service. TVDEs enjoy fewer restrictions than taxis, namely they are exempt from price controls and vehicle quotas, but public hailing and parking in taxi ranks are prohibited. As described above, TVDE drivers are also regulated and given statutory rights.

3.2. Positions of Key Actors

Government

The Portuguese government spent one year preparing the law before it was sent to parliament for discussion (Governo, 2017). The environment Minister, João Matos Fernandes, defended the government’s proposal by arguing that it regulated working conditions1 and was aligned with consumer needs.2 The minister also sought agreement with the PSD alluding to worker rights (a banner of the left);3 he defended the regulatory differences between TVDEs and taxis, despite the criticism from the left parties,4 which considered TVDEs and taxis as providers of identical services. The government explicitly excluded the implementation of TVDE quotas.5

Political Parties

Of the two left parties, the BE was more strongly opposed to the proposal; the party presented an alternative draft law for TVDEs (BE, 2017) and proposed revising taxi regulations so that the TVDE and taxi regulations were more in harmony.6 The BE also demanded a maximum quota of 25% of TVDEs in relation to the number of taxis by municipality,7 and that the municipality should have autonomy in the licensing of TVDEs. These proposals were rebutted by the PS and the government.

The PCP, like the BE, also considered that TVDEs provided the same services as taxis and invoked the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruling (CJEU, 2017). However, the party chose to propose changes to the government proposal rather than aligning with the BE draft law or presenting a proposal of their own (PCP, 2017, 2018). After criticising the operation of DPs,8 the PCP demanded that both platforms and TVDE vehicles be licensed (in line with the requirements for taxis).9 PCP also wanted TVDE and taxi drivers to have the same training and contractual safeguards.10 Finally, the party also demanded quotas for vehicles,11 price regulation for trips,12 and that DP operators should have open offices in Portugal.13

The PSD, the centre-right party, presented its own draft law (PSD, 2017) and subsequently proposed changes to the initial draft law (PSD, 2018). In the general discussion, the party declared its support for DPs and new business models14 and then focussed its discourse on work conditions and work precariousness;15 it criticised the government proposal as excessively deregulatory16 and noted the disarray of the left in the discussion on TVDE legislation.17

The other centre-right party (Centro Democrático e Social - Partido Popular, CDS-PP), also presented changes to the government proposal (CDS-PP, 2018). The CDS-PP supported regulating TVDEs in line with consumer preferences and enabling a competitive market in private transportation.18 The party disagreed with the government strategy of requiring the setting up of national TVDE operators and doubted this would impact the work conditions of TVDE drivers.19 The CDS-PP was also against the introduction of the TVDE quotas demanded by the left.20

The PS concurred that the promotion of innovation was key21 and underscored the importance of reviewing the government proposal to safeguard workers and users.22 However, it put forward three changes to the government proposal in an attempt to accommodate the positions of other parties - the most notable change was the inclusion of the work contract clause in the final draft (PS, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c).

Other Actors: Taxi Associations, Digital Platforms and TVDE Operators

The National Association for Road Transport of Passenger Cars (ANTRAL)23 and the Portuguese Taxi Federation (FPT) were the incumbent taxi associations. These taxi associations were against the government’s draft law24 and their interests were aligned with the demands of the parties on the left: they demanded either the prohibition of TVDEs or the same regulatory framework as the taxi sector.25 The taxi associations organised three major strikes between 2015 and 2017, protesting against both TVDEs and the law; this caused havoc in the larger cities - Lisboa, Porto, Faro - and included explicit violence against TVDE vehicles, TVDE workers and journalists.26 In 2018, the taxi associations protested again after the passage of the TVDE law.27

The DPs were generally favourable to the law.28 In 2016, both Uber and Cabify expressed their views on the first draft government proposal. Cabify complained that it had not been included in the consultation process and demanded that the new law should favour loyal market competition through some price regulation,29 the inclusion of existing taxis and taxi drivers in the DP market,30 limitations on fleets (a minimum of seven cars per TVDE operator and a maximum age of seven years for cars31), extended driver training (partially supported by DPs32), and driver exclusivity.33 For its part, Uber criticised some minor operational details, including the prohibition of TVDE traffic in taxi lanes34 and wanted the length of driver training to be specified as 30 hours.35

The TVDE operators are represented by employer associations. Two employer associations for this sector, the National Association of Transporters using Electronic Platforms (ANTUPE) and the National Association of Alternative Transport Partners (ANPPAT) were created in December 2016. The TVDE operators that hire the drivers and negotiate with the DPs are the members of ANTUPE and ANPPAT. The comments from these associations about the new law were mixed: both supported the idea of twelve-hour workdays for drivers36 but demanded TVDE quotas, a limit on the number of TVDEs and higher prices.37 ANTUPE considered that this law puts TVDEs at a disadvantage when compared with taxis as the former were required to have newer fleets, stringent sanctions on driver, and more transparent invoicing.38 ANPPAT expressed concern about the division of revenue: the DPs retain large commissions and leave TVDE operators and drivers with margins insufficient to cover costs.39

The President of Portugal

President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa focused on defusing the tensions between the coalition opposing the law and the coalition supporting it. In October 2017, he managed to convince the taxi unions to cancel a protest scheduled for 17 October and agreed to meet with them; this followed a protest on 10 October which had been marred by violence and confrontations with the police40. In April 2018, the president vetoed the first version of the law approved by the parliament. He cited the CJEU ruling to argue that TVDEs provide an identical service to that of taxis,41 and highlighted two main reasons for the veto: firstly, the legislation only addressed TVDEs and did not revise the status of taxis, which made the regulatory context unbalanced in favour of TVDEs;42 secondly, the absence of quotas and fixed prices for TVDEs were obvious advantages which were not offset by the provision prohibiting them from using bus lanes and taxi ranks. TVDEs should pay a tax to cover some of these benefits; however, the tax considered in the decree law was negligible.43 Finally, when the second version of the law was approved, the president agreed to meet with taxi unions again even though the unions recognised that he had no power to change the new law.44

3.3. Enactment Process

After the Lisbon District Court - first civil section issued a statement declaring that TVDEs were illegal in April 2015,45 the DPs contested this decision and continued to operate. In May 2016, the Secretary of State for the Ministry of the Environment formed a workgroup to discuss the contents of the new TVDE law. After a consultation process with key actors, the Portuguese government led by the PS sent a proposed bill to parliament in January 2017. Formal discussion of the law was initiated in March with the contributions presented from left parties: the BE offered their own draft law, while the PCP suggested changes to the government’s proposal.

The parliament responsible for the discussion and approval of the TVDE in 2017 and 2018 was constituted following the 2015 elections. The centre-right party, the PSD, had the most Members of Parliament (MPs) - 89 - and the centre-left, the PS, was the second party with 86 MPs. The left had 36 MPs (15 representing the PCP, 19 for the BE, and 2 for the Partido Ecologista “Os Verdes” - PEV). The other centre-right party (the CDS-PP) had 18.46 With a total of 230, there were two possible majorities for the approval of the TVDE law: an agreement between the centre-left and the left (which would be coherent with the existing parliamentary coalition that supported the government), or an agreement between the centre-right and the centre-left.

After the general discussion in March 2017, all parties agreed to delay the specialty discussion and the final vote, which were held only one year later in March 2018. During that period, all parties reviewed the government’s proposal and compiled a list of additions and modifications. Like the BE, the PSD prepared an alternative draft law, which was presented in June 2017. The three draft laws - the government’s proposal and the BE and PSD draft laws - were sent to public institutions (the Competition Authority - AdC, the Authority for Mobility and Transport - AMT and the National Association of Portuguese Municipalities - ANMP), the taxi associations ANTRAL and FPT, the DPs Cabify and Uber, and to the Consumer Defence Association (DECO Proteste) for consultation and feedback. By the end of January 2018, the parties presented their final list of modifications to the government proposal or their own draft law (the case of the PSD and CDS-PP), which were to be voted on in the specialty discussion in mid-March. The PSD and PS both submitted a new list of modifications less than two weeks before the specialty discussion.

In the specialty discussion, all the provisions of the law were voted on and the government’s law proposal was substantially modified; it was evident that the PS and PSD had agreed on what the final draft should be. During the discussion, the PSD and the PS voted together in all but five modifications (four of which had been proposed by the CDS-PP and one by the PCP); the PSD abstained on these and the PS voted against them (none were passed). The PS did not abstain in any vote and all modifications proposed by the party were approved. Several modifications proposed by the PSD were also approved. Only one proposal from the CDS-PP and another from the PCP were approved. None of the BE’s proposed modifications were approved. In the final vote, the PSD, the PS and the CDS-PP voted for the revised law proposal, while the PCP and BE voted against.

After the law was approved by parliament, it was sent to the president for ratification. However, the president vetoed the law, and it went back to parliament. The PS and PSD added some modifications (most notably, they raised the tax that DP must pay to operate) and approved the new proposal together, although the PCP and BE voted against and CDS-PP abstained. This second proposal thus became the decree law that is currently in place.

In late September and early October, less than two months after the law had been approved, the PCP and BE tried to change it: the PCP (through the Green Party PEV) proposed draft laws on TVDE driver training, TVDE price regulation and municipal regulation; the BE presented a parliamentary proposal to revoke the law that had just been approved. The left (the PCP and BE) voted in favour of all these draft laws, while the PS, PSD and CDS-PP voted against.

To conclude this section, we would like to stress that even though the centre-left government had been made possible thanks to a parliamentary agreement between the centre-left (PS) and the left (PCP and BE), it was the centre-left and the centre-right (PSD) that voted together to approve the TVDE law, and explicitly against the demands of the left.

4. Spain: Fighting Precariousness by Limiting Liberalisation

4.1. The Regulations in Place

In Spain, the Royal Decree-Law 13/2018 is the latest regulation of the VTC market. It was preceded by two Royal Decrees (RDs): firstly RD 1057/2015, and then RD 3/2018, which was similar in content to RD 1057/2015 and approved only a few months before RD 13/2018.

These three RDs agree that VTCs should be limited to a quota proportional to the number of taxis. RD 1057/2015, which changes two articles of the Reglamento de la Ley de Ordenación de los Transportes Terrestres (the regulation of land transportation), defines a minimum of seven vehicles per TVC company (thus excluding small companies from operation), limits VTCs to one for every 30 taxis - although the comunidades autónomas [autonomous communities] could opt for fewer restrictive limits - and circumscribes VTCs to local transportation (80% or more should be local transportation, i.e. within the comunidade that licensed the VTC).

This regulatory change was contested by the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC, the competition regulator), Unauto VTC (one of the major VTC operators), Uber, and Maxi Mobility Spain (another VTC operator), and was partially upheld by the Tribunal Supremo (the Supreme Court). This led the government to annul the changes made to the Reglamento, and instead change the Ley de Ordenación de los Transportes Terrestres in RD 3/2018.

That RD lasted five months. In September 2018, the minority government led by Pedro Sánchez (that had replaced the Rajoy government in June following a no confidence vote) issued RD 13/2018, which increased VTC restrictions. While the quotas for VTCs were maintained, VTCs were only allowed to operate locally; this meant that journeys should start in the comunidad where the licence of operation was issued. The comunidades autónomas not only issued licences but could also change service regulations that might impact VTC operation in the respective comunidade. VTC companies were given a transitory period of four years to adapt to these new regulations.

4.2. Positions of Key Actors

Government

The regulation of VTCs coincided with different political contexts: in 2015, RD 1057/2015 was issued by the first Rajoy government that had an absolute majority in the congress and the senate; in 2018, RD 3/2018 was issued by the second Rajoy government in April, when the PP no longer had a majority in parliament; finally, RD 13/2018 was issued in September by Pedro Sánchez’s first minority government (after PP had been ousted by a no confidence motion approved by parliamentary vote in June and replaced by PSOE).

Nonetheless, there has been continuity in the decrees: VTC quotas (relative to the number of taxis) and limits on VTCs’ geographical operation, thus making VTC operations similar to that of taxis. Ley 9/2013 had already changed the transportation regulation law and included a new framework for the hiring of vehicles with a driver. Despite affecting a small market at the time - the hiring of vehicles with drivers was mostly limited to premium limousine services, weddings, and funerals - the regulations in this law were the point of departure for the new VTC regulations. This allowed the PP government to claim that RD 1057/2015 was reducing the existing regulations on VTCs and liberalising the sector.47

The DPs and the competition regulator contested RD 1057/2015 and the constitutional court partly upheld their complaints. The government then issued RD 3/2018, which elevated the regulation to the status of law. The Minister of Development announced that the law had a national scope and vowed to guarantee an equilibrium between VTCs and taxis,48 stressing that the effort to regulate this balance had relied on quotas since the 1990s49 (although abandoned by the 2009 Omnibus Law when there were still very few VTCs). The minister claimed that the government had to rein in on the discretional regulations of the comunidades autónomas (namely, Cataluña and Valencia) that limited VTC operation, after conflicts between taxis and VTCs had occurred.50 The government recognised that the current regulations had failed as the national average of one VTC per nine taxis was above the 1/30 target - one comunidad autónoma having a ratio of 1/3. The new RD, which had achieved a negotiated consensus from taxi associations and VTC associations, aimed at maintaining a healthy competition between taxis and VTCs51 at the national level, and preserving market unity across the country.52 It followed up on the 2017 regulation that forbade the transmission of VTC licences.53

With the change of government in the summer of 2018, when a PSOE minority government took office, the government’s position on the VTC issue changed and a new RD was approved. Ábalos Meco, the new Minister of Development, declared that the service provided by taxis and VTCs was similar54 and that the VTC legislation should be revised to foster even more competition.55 In a few months, the national ratio of VTCs per taxis had risen from one-to-nine to one-to-six (with new licences expected to be approved by a court ruling) and the new government was inclined to protect the incumbents.56 Contrary to the position of the PP government, which had defended that VTC regulation should be national, the new government proposed that VTCs should be regulated by the comunidades autónomas and their operations limited to within the comunidade autónoma that issued the respective VTC licence;57 it argued that VTC should be regulated locally like almost all other transportation services.58 The recommendations of the EU were not used to justify the government’s regulation.59 Nonetheless, the government argued that the government’s proposal was aligned with these recommendations.60

Political Parties

Ciudadanos, the most liberal of the main parties in the VTC discussion, argued when voting on RD 3/2018 that the new regulation limited the development of VTCs and market competition in the sector.61 Ciudadanos defended less intervention - reduced licensed costs, flexible tariffs, and user freedom of choice62 - opposed VTC quotas and geographical limitations63 and demanded the integration of the VTC sector with the traditional taxi sector through competition.64 Ciudadanos was also against RD 13/2018. In the parliamentary discussion in October, Ciudadanos argued that the bill destroyed the VTC sector: firstly, the new RD would fragment the VTC sector as each comunidade autónoma could regulate it locally (which contradicts EU recommendations);65 secondly, the RD legalised an expropriation of licences, as those issued as being valid across the nation would now be converted to local licences;66 and thirdly, while the central government passed responsibility to the comunidades, decentralisation would mean the end of the VTC sector in some of the comunidades autónomas that opposed VTCs.67 Ciudadanos underscored the importance of the VTC sector and called for a new regulation to protect VTC workers,68 arguing that the government had adopted an unreasonable stance against VTCs.69

In the discussion on both RDs, Podemos maintained a simple and straightforward discourse against precarisation, vulture capitalism and offshore companies. When RD 3/2018 was under discussion, Mayoral Perales heralded the taxi sector for being the single force in opposition to TVCs,70 the safeguard of both the sector’s interests and those of public service,71 and the protector of the Spanish economy against its “uberisation”.72 The party’s greatest concern was the “uberisation” of the economy73 and its threat to public regulations and conditions for workers.74 It considered that the TVC quotas imposed by the RD limited VTC development, and thus supported it,75 despite arguing that more far-reaching legislation could be approved. Podemos maintained this line of argument in the discussion of RD 13/2018,76 underscoring the precariousness of the jobs created by the DPs77 and criticising the role of the competition regulator in its defence of VTCs.78 Although recognising that the new RD had shortcomings, Podemos defended it because it further limited TVCs and thus defended worker conditions;79 the party again complimented the efforts of the workers of the taxi sector.80

PSOE, the centre-left party, supported RD 3/2018 arguing that the bill should be temporary and hinting at further discussion with other actors81 - namely, the comunidades autónomas - but did not support the approval of a draft law (proyecto de ley) in parliament.82 Estebán Ramos argued for similar TVC and taxi regulations,83 defended the benefits that new technologies brought to the users84 and urged the politicians to find the best regulations85 that protected workers and public interest. Despite agreeing with Podemos on the latter86 PSOE criticised it for not presenting any reform proposals for the taxi sector and for the hostility against Ciudadanos, thus derailing further parliamentary agreements.87 In the debate on RD 13/2018, the PSOE again stressed that VTC and taxi regulations should be similar;88 it was therefore necessary to grant regulatory power to the comunidades autónomas89 and to have VTC regulation to protect workers90 because this protection should accompany (and not hamper) technological progress.91 The PSOE also argued against the draft law, claiming that further discussion would result in regulatory uncertainty;92 the party claimed the government decision was based on the concerns of all relevant actors, despite conceding that not everyone was pleased with the new RD.93

The PP, the centre-right party, argued that RD 3/2018 protected the taxi drivers94 - criticising the rhetoric of Ciudadanos against the incumbents95 - and underlined the role of the government in increasing the number of VTC inspections.96 Herrero Bono presented all the laws approved by the PP since 2013 as protective of the taxi sector,97 and blamed the Zapatero government for changing a law in 2009 that deregulated individual transportation licences98 and which VTC operators exploited.99 On the other hand, the PP opposed the approval of RD 13/2018 and supported a new draft law.100 Arguing that the previous RD approved by the PP had allowed taxis and VTC to operate peacefully,101 Herrero Bono criticised the new RD as an attempt to transfer government responsibility to the comunidades autónomas,102 while not including them in the decision-making process and not pleasing any relevant actor103 other than Podemos.104 The PP accused the government of legislating excessively (and ineffectively) despite (because of) its weakness,105 and presented recommendations to reform the taxi sector.106

Other Actors: Taxi Associations, Digital Platforms and VTC Employer Associations

Taxi associations in Spain opposed the implementation of the DP business model. Taxi drivers and taxi associations from Barcelona107 and Madrid108 were the most vocal (and the most affected by the arrival of Uber in 2014). In Cataluña,109 in particular, they managed to find regional allies.110 In general, taxi drivers agreed with the regulations of the VTC business - particularly, with the imposition of VTC quotas in relation to taxis - and tried to push these regulations further, with the goal of eliminating VTC operation.111

Digital platforms, on the other hand, fended off the opposition from the incumbent taxi sector by exploring a legal loophole in the regulation of public transportation and established in the Spanish market by purchasing VTC licences.112 This represented a significant investment that was threatened by the Spanish legislation of limiting licences in relation to the number of taxis, and of restricting licences’ validity to the comunidade autónoma that issued it.113 As such, DPs and VTC employer associations were consistently against the regulations adopted by the Spanish government,114 and appealed to the courts to keep the licences they had invested in.115

4.3. Enactment Process

The approval process of RD 1057/2015 was distinct from that of the RDs of 2018. As RD 1057/2015 modified the Reglamento de la Ley de Ordenación de los Transportes Terrestres, approval was not required from the Spanish congress. The government consulted with entities of the public administration116 and with the comunidades autónomas117 for the draft version and received feedback from additional entities118 before the RD was published. However, the CNMC was against the new regulation and in early 2016 initiated an administrative litigation against it. In 2018 (June 4), the court decided that the first two paragraphs of Article 181.2 (which referred to the ownership of at least seven vehicles by the operating companies) should be annulled.

In April 2018, RD 3/2018 (which had the same content as RD 1057/2015 but was issued as a law and not a regulation) was approved after a vote in congress. The PP, PSOE, Podemos and other minority parties voted in favour of the law, while one MP from the PSOE, and one from Podemos and Ciudadanos abstained. However, Podemos, Ciudadanos and one PSOE MP then voted for the modification of the government law through congress (a draft law), but the PP and PSOE voted against this initiative.

The vote for RD 13/2018 was different. Again, the congress of deputies was called to approve the RD from government, this time led by the PSOE. RD 13/2018 was approved by the PSOE and Podemos with votes against from PP and Ciudadanos (the minority parties were crucial for the approval of the law). Regarding the modification of the law, the PP and Ciudadanos voted to modify the law through adraft law, while PSOE and Podemos voted against. Again, the minority parties were crucial for the approval of the modification to the law. However, this draft law expired when the congress of deputies was dissolved in March 2019.

5. Comparing Portugal and Spain

Having presented the empirical research in the previous section, we now compare the two cases. Table 1 summarises the debate in the Portuguese parliament, showing the alignment between the PS and PSD in the discussion on the main issues in the law, and the division between the centre-left (PS) and the left (BE and PCP). Despite this division, TVDE workers’ conditions was a matter of concern for all parties involved in the discussion.

This division shows a parliamentary coalition that supported the new law - the centre-left and the centre-right - which was joined by the representatives of the digital platforms (as presented in the previous section). On the other hand, the left - the BE and PCP - formed the parliamentary coalition against the law, which was supported by the incumbent taxi associations, and later joined by the president, who vetoed the first law and demanded a revision from parliament.

Table 1 Portuguese Case: Analysis of the Discussion in Parliament.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

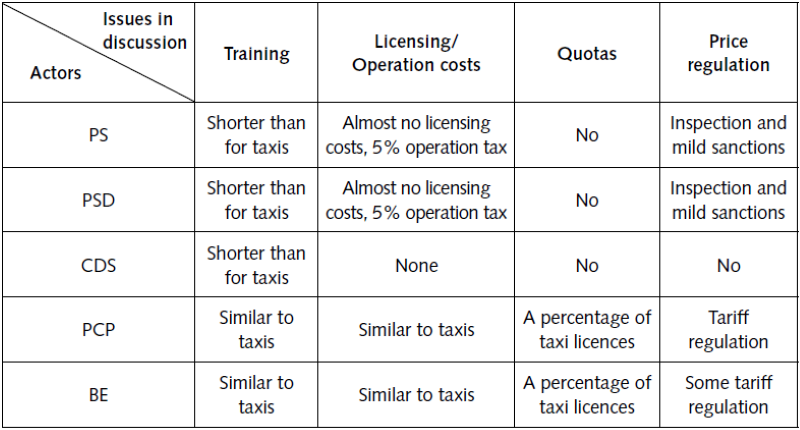

The Spanish case is summarised in Table 2. It shows that whereas the PSOE aligned first with the PP and then with Podemos to enable VTC legislation that restricted VTCs, Ciudadanos was against both RD 3/2018 and RD 13/2018. The reason for this is that the introduction of VTC quotas was consensual among all parties except Ciudadanos. In fact, the parliamentary discussion about VTCs in Spain was focused on VTC quotas and VTC licences - how many could be issued, and who or which institution should issue it. This last point was a source of disagreement between the centre-right and the centre-left; the latter was joined by the left in the approval of RD 13/2018 that mandated the comunidades autónomas to regulate and issue VTC licences.

Therefore, the coalition in Spain that favoured RD 13/2018 was composed of the centre-left, the left and the taxi associations. Against this winning coalition, the platforms and the right formed the coalition opposing the new law, joined by the centre-right when PSOE was in government.

We now compare the two cases. The winning coalition in the two countries was led by the centre-left (PS in Portugal, PSOE in Spain), which headed a minority government in both cases, supported by parliamentary agreements with the left (BE and PCP, in the Portuguese case, and Podemos, in the Spanish case) when the laws were approved. However, the centre-left behaved differently in the two countries: whereas in Portugal it joined the centre-right, in Spain it joined the left. This shows that centre-left parties’ positions and preferences are not rigid, as some dualisation literature suggests.

The laws were also radically different. In Portugal, the aim of the legislators was to regulate the new service - seen as differentiated from the traditional taxi service - by creating new frameworks for operation that included the platform, the TVDE operator, and the drivers (who were a main concern). The Portuguese law thus regulates the TVDE service as a competitor to the traditional taxi service (Tomassoni and Pirina, 2022). Outsiders’ work conditions were a key point of discussion, and greater regulation of the TVDE service meant protecting outsiders and simultaneously accepting greater competition in the sector, which led to a deterioration of the insiders’ labour market conditions (taxi drivers).

In Spain, the aim of the legislators was to limit the development of VTCs; it was decided to do this using quotas of VTCs in relation to traditional taxis (consensual among all parties except Ciudadanos in Spain, but highly contested in Portugal, where only the left supported it). The discussion revolved around how this business operates, namely in relation to the number of licences issued; the law does not include any reference to VTC worker conditions. By restricting the number of VTCs, the Spanish law relegates VTC to a limited service both geographically and in terms of licences, and preserves the traditional taxi service.

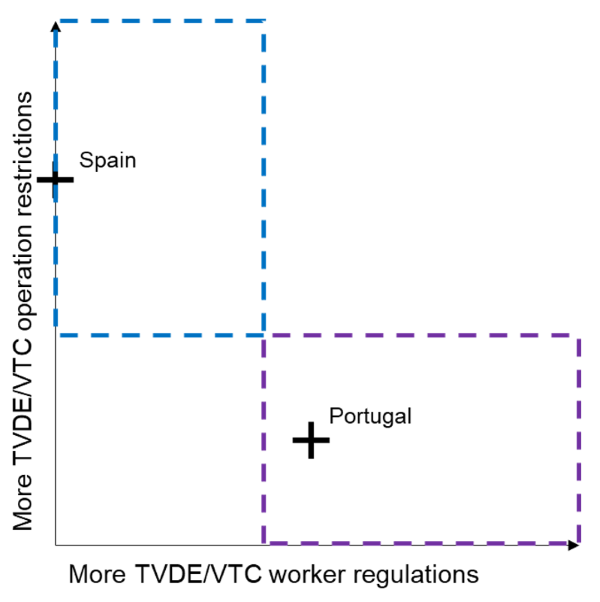

Figure 1 shows the difference in the impacts of the new pieces of legislation of greatest concern. By regulating the service, the Portuguese legislation of TVDE acknowledges a new group of workers in the sphere of regulated (or to be regulated) labour. However, by lowering the standards of work regulation in this field, it may contribute to further deregulating the traditional taxi service. In Portugal, there is therefore a lowering of standards that allows the inclusion of one new segment of labour.

In contrast, the Spanish regulation of the VTCs focused on the service level and pushed the VTCs to the traditional taxi operation standard. The taxi worker standards were not affected, but the VTC workers were not recognised as a new segment of workers.

The legislation approved in the two neighbouring countries thus led to two different outcomes, which may suggest that the MME category advanced by the CPE literature may not be sufficient to explain new regulations of the labour market, particularly after the Great Recession of 2008 in Southern Europe.

Concluding Remarks

The political context in Portugal and Spain was similar during the discussion of the TVDE and VTC laws: there was a minority centre-left government (the PS in Portugal; the PSOE in Spain) supported by a parliamentary agreement with the left (the BE and PCP in Portugal; Podemos in Spain). However, as we have shown throughout this paper, the laws approved were very different in content and point to distinct solutions to the problems posed by the emergence of TVDEs and VTCs in the Iberian countries. The Portuguese law regulates the TVDE service as a new private transportation service and integrates a new set of workers, while contributing to the liberalisation of the private transportation service. On the other hand, Spanish law restricts VTC operation, both in numbers and geographically, thus approximating VTC regulations to those of the incumbent taxis. The Spanish law preserves the status quo at the expense of limiting the expansion of the sector. This points to a different positioning of the centre-left in the two countries under analysis.

To explain this divergence, we have argued that different conceptions of solidarity were found in the two countries. In Portugal, market expansion was seen as positive for vulnerable workers as this gave them access to the labour market. Moreover, the centre-left not only liberalised the sector but also included some minor norms on labour contracts. The opposite happened in Spain, where the strategy used to fight precariousness was to constrain the growth of this sector. Solidarity with vulnerable workers meant containing markets.

From our perspective, this study has some implications for the field of comparative political economy. The literature on dualisation has focused on describing the mechanisms that led to growing labour market segmentation in contemporary capitalism. Recent debates have recently moved forward to discuss how to revert this process and thus foster greater solidarity. The way to address labour market segmentation is, however, controversial. As our study has shown, there are two different ways to achieve this. The first sees market expansion as a feasible strategy, namely when matched with minor reforms in terms of labour contracts. Job creation and the establishment of minimum regulations is understood to be the best way to protect vulnerable workers. It is also thought to foster economic growth. The second approach follows the opposite rationale: market containment is seen as crucial to avoid the spread of precariousness. Safeguarding traditional sectors, like the taxi sector, is considered as necessary to foster solidarity among workers. More solidarity therefore means bringing more workers to regulated sectors (Riesgo Gómez, 2023).

It is essential that future research assesses the impacts of the laws, which have yet to be evaluated and analysed. Following their approval, some of the intended effects materialised but others did not; moreover, revisions of the current law focusing on the drivers’ contracts are under way or expected soon in both countries,119 which can change the regulatory framework that was analysed in this paper. In addition, TVDE/VTC drivers have formed unions and TVDE/VTC employer associations have coalesced and grown, which has changed the context for future discussions. This clearly demonstrates that TVDEs and VTCs are now an enduring reality in both Portugal and Spain.