1. Introduction

Throughout this article, we seek to use an ethnographic case to reflect on different ways of thinking about dwelling. We show how in ‘Minha Casa, Minha Vida’, the largest public housing policy in Brazil, the architecture is designed with generic spaces, mass-produced and which cannot be modified according to the residents’ needs. Located in one of the condominiums in this project, the Dja Guata Porã Garden1, created by indigenous leaders, demonstrates another form of relationship with the urban landscape. The garden represents a change in the urban fabric of that place and seeks to bring traditional modes of knowledge to the center of the project, which are reinvented in contact with new techniques. For this reason, we have proposed that this project of indigenous horticulture, with pedagogical purposes, is a gap in the urban fabric and creates a territory that organizes itself based on multispecies relationships.

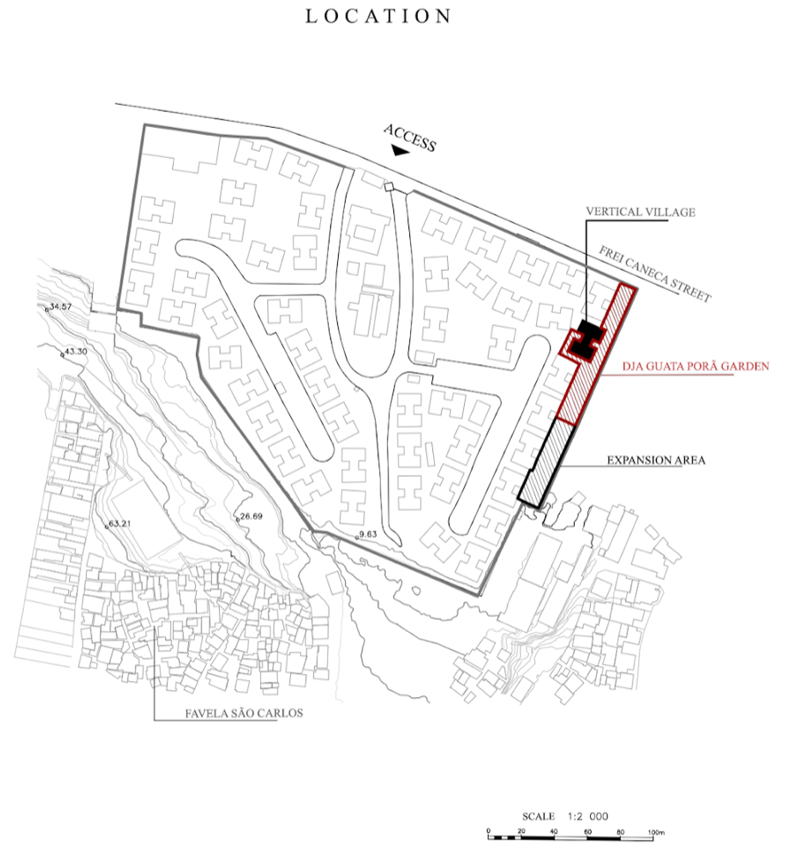

In the first part, we will present the popular housing program of the Brazilian federal government called ‘Minha Casa, Minha Vida’ (translated to ‘My House, My Life’, from now on referred to by its acronym ‘MCMV’) and the existing criticisms regarding the urban project. In the second part, we will introduce the Dja Guata Porã Garden and, according to one of its leaders, how they are “transforming the city into a forest”, as seen in Figure 1. Later, we will present another way of thinking about that space from a multispecies perspective, which takes into account the non-human agents of space. At the end, we point out theories that seek to think about housing, architecture and urbanism that take into consideration indigenous cosmologies.

The fieldwork on which this research is based first began in 2016, following a group of residents from the Vertical Village that participated in a municipal program building a garden in a slum behind the building. The project was led by Niara do Sol. The year after, we followed the emergence of another vegetable garden as part of a museum exhibition about indigenous cultures in one of Rio’s most famous museums, Museu de Arte do Rio (MAR). Later, in 2018, plants and seedlings from the previous gardens were taken to the Vertical Village and started the Dja Guatá Porã Garden, which is analyzed here. The fieldwork consisted of several weekly visits to the gardens and participation in its activities during two years, first in 2016 and later in 2019. In between, contact was kept with the participants of the gardens and more sporadic visits happened. In 2021 two in depth interviews were recorded in video with two participants.

This article addresses a case study of a unique situation. The exceptional character of the analyzed case is due to two main reasons: the location of the condominium, one of the few of a gigantic national project located in a central region of the city, and also the occupation of one of the buildings by indigenous residents and the space in the surroundings by the vegetable garden project examined here. In addition to presenting the case that has several interesting features, we also make more general notes about the MCMV and Brazilian urbanism, based on this exception to the rule. We mainly show how the Dja Guata Porã Garden’s perspective on dwelling is different from that of the MCMV. For the reasons that will be presented here, we argue that the Dja Guata Porã Garden represents a gap in formal urban space, from which a different way of inhabiting the space is revealed, coming from indigenous cultures.

This spatial contrast is analyzed with the concept of urban gap, deduced from the work of anthropologist Tim Ingold (2010). The author talks about the asphalted surface breached by roots that eventually cracks, allowing plants to grow: “Wherever we choose to look, the active materials of life are winning out over the dead hand of materiality that would snuff it out.” (Ingold, 2010). So, to think about the idea of an urban gap is to return to Ingold’s conception of how to bring things back to life through the gaps in the city’s formal space. Today, the garden is found in a cornered plot between buildings on one side and the wall on the other. It is grown in a gap in the pavement, a space between.

We consider ‘urban gaps’ spaces in which their uses and adaptations change the preconceived idea for that space. Often unofficial, they tend to be out of urban design manuals. Through people who - along with their collaborators - create new city realities, ‘other’ ways of living from the gaps. Even outside the mainstream thinking of urban planning, they exist in the daily lives of different populations, in the form of vegetable gardens in residual spaces of the land, common spaces organized for the gathering of residents, among other forms, which can only be conceived by those who create such gaps. These actions, for the most part, are carried out by non-architects and work under other logics of land occupation. It is not about a general crack in the design paradigm, it is about small gaps in the urban fabric that, when they meet, can form a new urban plot in which the main objective is to meet the differences in the city space.

How can we, based on gaps, reflect on a way of thinking about the city that derives from an “anthropological intrusion in the field of design” (Cançado, 2019)? We propose that it is possible to observe these places as opportunities for multispecies circulation and conviviality spaces.

2. The “Minha Casa, Minha Vida” housing program

The Dja Guata Porã Garden was created by indigenous leaders and is located in the city of Rio de Janeiro, inside a condominium that is part of the MCMV, the largest popular housing project in Brazil. As in most Brazilian cities, the landscape described in the previous scene is nearly paved in full. Urban life, in most cases, is paved life. On this topic, Ingold (2011) would say that the almost total coverage of land in urban areas is what gives citizens the illusion of a life without land. The earth beneath the pavement becomes an abstraction, seen only in small, controlled spaces. By alienating city dwellers from their relationship with the land, it also alienates their relationship with food production and other ways of living and relating to space.

The MCMV program was created by the Federal Government of Brazil in response to the international economic crisis of 2008, aiming to boost the economy based on the civil construction sector (Rolnik, 2015). This is the main public housing program in the country, and even after its implementation, Brazil has a housing deficit of more than five million people2. MCMV has three types of financing: houses, buildings and towers, and serves three different income brackets. According to official information, the MCMV is also the largest housing program in the history of Brazil, having built around five million homes. By 2019, approximately 20 million people were served, equivalent to 10% of the Brazilian population (Instituto Escolhas, 2019).

Despite the grandeur of the undertaking, several architects and urban planners point out problems in the project. According to architect and urban planner Raquel Rolnik (2015), the flaws are mainly due to the way the policy was developed - seeking to respond not only to a demand for popular housing, but also for economic reasons and interests in the construction and real estate sectors. As a result, the architectural projects were prepared in such a way as to privilege the replication of housing models and with very little - or often not any - adaptation to the urban design of the location. All these factors only reiterate the already existing socio-spatial inequality of the Brazilian urban space (Rolnik et al, 2015).

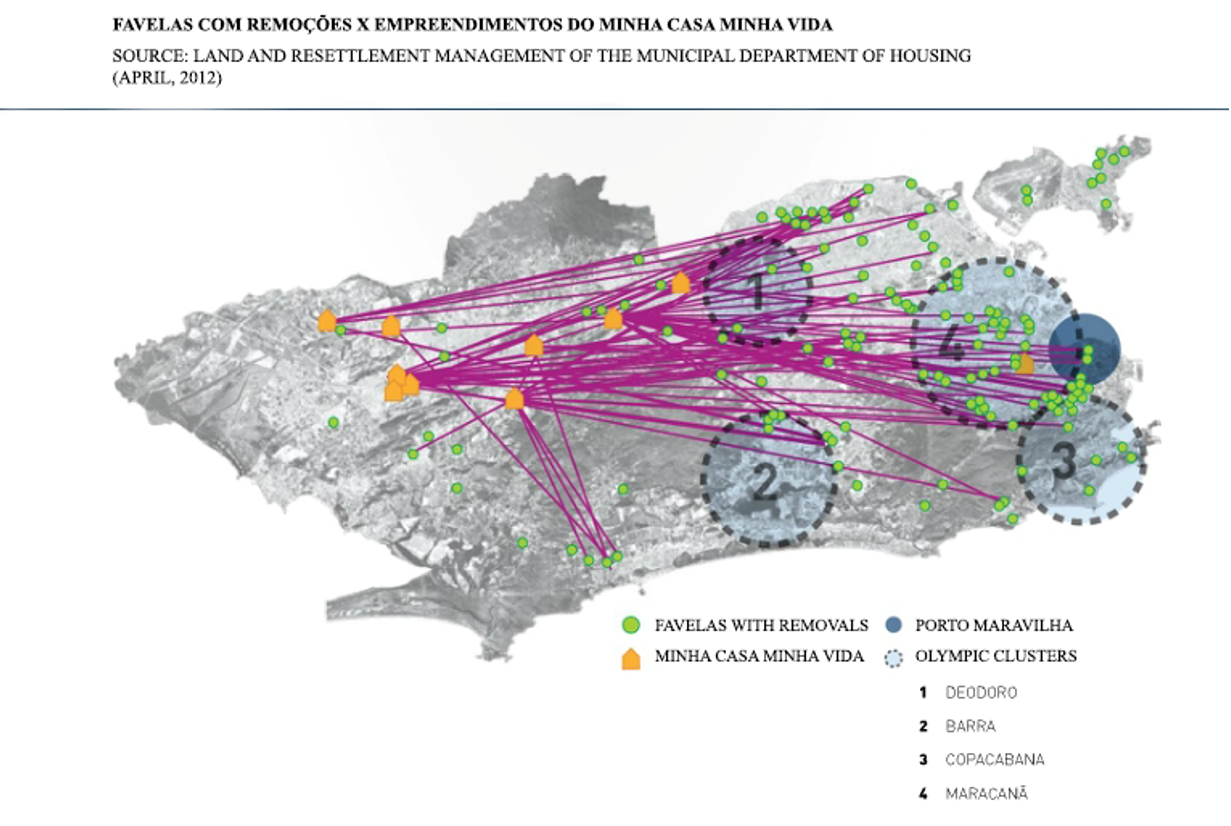

In the case analyzed here, we have the example of removals that were made in Rio de Janeiro, in the context of mega events (World Cup in 2014, and Olympics in 2016), as shown in Figure 2. During this period, a large number of people were removed from their homes for the construction of infrastructure for international events3, most of the time through urban projects that overlapped with the master plan already prepared for that region. In addition, when people were removed from their homes, compensation, which was insufficient, did not cover the costs of moving, leaving financing through the MCMV housing program as the only option.

Lucas Faulhaber, Lena Azevedo. Publisher, Mórula Editorial, 2015. Translated by the authors

Source Figure 2 Removal of communities’ x Minha Casa Minha Vida Developments. Source: Map from the book SMH 2016: remoções no Rio de Janeiro Olímpico

During the period of these international sporting events, the indigenous people, current residents of the “Vertical Village”, occupied since 2006 a building of historical value in the surroundings of the Mário Filho Stadium, the Maracanã, one of the main football stadiums in the country. The occupation was characterized by the almost total presence of indigenous people of different ethnic groups who lived in the former building of the Indian Protection Service and Museum of the Indian, a place that became known as Maracanã Village. However, the City Hall of Rio de Janeiro had drawn up an urban plan in which the occupied area was intended for the parking lot of the football stadium, to serve the Football World Cup. After resistance, the residents were violently removed by the military police on March 22, 2013.

Among the residents who were forcibly removed, only a part agreed to be relocated by the City Hall. In 2015, through social income4, some of the indigenous residents of “Aldeia Maracanã” received apartments in the condominium in the Estácio neighborhood, part of the MCMV housing program. The building, inhabited almost entirely by indigenous people, was called the Vertical Village by residents.

The location of Estácio’s MCMV is quite different from the other developments in the program, as the land is in the central area of the city, with access to the existing urban infrastructure. It is the only complex built within planning areas 1 and 25, with a wide range of transport options (ENTRE, 2019). The program was planned to serve three income groups, in this case it is Group 01, aimed at families with the lowest income in the program. Developments in Range 01 usually have little mobility in terms of living spaces, since the location and choice of land are made directly by local governments and follow a rigid standard of architectural design defined mainly by construction companies aiming at the lowest possible cost, resulting in low quality spaces (Rolnik, 2015).

The reason for the privileged location of this unit in relation to others in the MCMV is that it was built where the Frei Caneca Penitentiary Complex used to be, the first prison in Brazil, built in 1834. The demolition of the prison in 2010 opened a void in an extremely dense part of the city, making it possible to build such a large condominium.

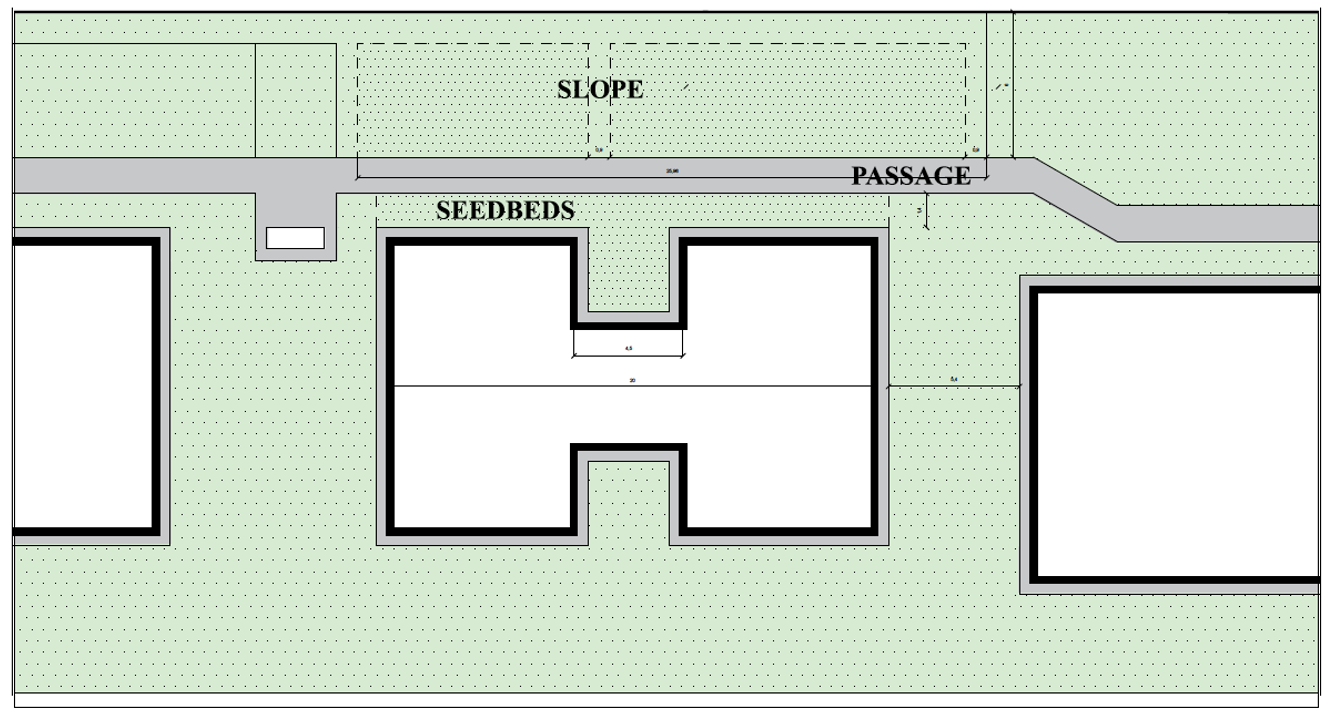

According to Amoedo (2019) the typologies of the former prison and the current residential condominium are similar, due to their implantation in standardized buildings and the spatial segregation in the clear division between private lot and public space, as seen in Figure 3 and 4.

“Compared to the old Frei Caneca Penitentiary Complex, the configuration of the MCMV housing complex presents similarities. Among them: the implantation of standardized blocks, the detachment of the urban territory, and the extreme demarcation between the public space and the private lot.” (Amoedo, 2019, p.56)

The following items were maintained from the penitentiary project: the old access portal to the prison, where the sign still indicates ‘Correctional Facility’ and is where, today, the residents’ association is located. Also still there is the stone wall that delimited the prison area. The wall dates back to the colonial period, when it was built by forced slave labor using whale oil to fix the stones (whale hunting has been prohibited in Brazil since the 1960s).

The architectural project is organized like all the others, by the logic of the condominium (as shown in the map in Figure 5), through the opposition between public space versus private space or city versus condominium and, consequently, the separation between housing and urban surroundings. The existing wall of the old prison was completed by new fences, isolating the entire perimeter, so the limits are an important part of the analysis of this space. In Rolnik (2001) we see the issue of physical barriers, walls, railings and watchtowers as a demonstration of a fragmented city, promoting controlled, protected areas of high or low income. The architect and urban planner describes this as a ‘broken space’ or ‘anticity’6, characterized by new forms of urbanity based on the denial of contact with the other.

The architectural project consists of buildings with five floors each, with a standardized floor plan in an “H” format (as visible in the floorplan in Figure 6). Apartments have an area of 47 m2, consisting of two bedrooms, living room, bathroom and kitchen. They feature simple volumes, five-story rectangles with small metal frames and are arranged on the ground in a contingent manner, seeking to fit in the best way to fit more. Altogether, there are fifty-three buildings, with twenty apartments each.

In gray we see the internal streets with sidewalk and in green the spaces between buildings

Faculty of Architecture at the University Santa Úrsula

Note Source Figure 6 Schematic base plate of the typology of the Minha Casa Minha Vida buildings

The free areas of the condominium have internal streets that are mostly used for parking. The free areas are characterized by the leftover spaces between buildings - like the location of the vegetable garden. These are quite standardized, since modifications in common spaces and any type of activity other than housing are not allowed. These characteristics preclude the alternation of land uses or the diversity of landscapes. It is a monotonous environment that keeps the architecture in place. And it does not act as a stimulus to local communities.

The Brazilian collective of architects ENTRE (2019) describes this type of standardized space from the action of ‘colonizing’ and also works with the concept of crack:

Colonizing a territory extensively and homogeneously. Colonization replicates an easily manufacturable form on a massive scale - one unit justifies proliferation: if we are going to build 1, why not build 31? The colonized landscape is an infinitely boring monoculture which eliminates local diversity. As it suppresses a lack by means of an excess, this reaction is an immediate and simplistic answer to changing social demands, which ignores the nuances of the various social fabrics it touches. To colonize is to condemn a space to stagnation, unless somehow, a crack allows for its subversion. (ENTRE, 2019, p.67)

3. The Dja Guata Porã Garden

It is in this context of the Vertical Village within Estácio’s MCMV that some of the residents got together, led by Niara do Sol, an indigenous daughter whose parents are from the Cariri and Fulni-ô ethnic groups, to make gardens. In the garden, Niara has the collaboration of two other residents of the Vertical Village: Dauá Puri7 and Elvira Sateré-Mawé. In the team, there are also apprentices in addition to several students and visitors who participate in activities and occasionally work as volunteers.

Today there are two gardens started by them: the first is located in one of the plots of land between the condominium and Morro do São Carlos. Niara initially received incentives from the Rio de Janeiro government’s Hortas Cariocas8 program. The second garden, called Dja Guata Porã and the subject of this article, is more recent and is being cultivated in the space between the building where they live and the wall that delimits the MCMV land.

The MCMV condominiums do not have a landscaping project, and the Dja Guata Porã garden is easily identified in the condominium due to the difference in relation to the surroundings. The area around the buildings and the construction sites has little to no vegetation other than grass, which is often tall and is only cut sporadically by the condominium administration.

In the middle of the arid landscape, the garden rises as a space taken by dense flowerbeds, tall trees and diverse vegetation that shades the path and climbs the wall. Flowers, insects and birds appear there (the contrast is shown in Figure 7 and 8). The stretch of path is cooler and more fragrant due to the shade provided by the trees and the planted herbs, unlike the rest of the slope which often has abandoned (and foul-smelling) garbage.

Both gardens were launched with the hope they become catalysts for change, giving others the opportunity to learn how to plant so they can start their own gardens. The participants intend to mobilize changes in the landscape of the condominium and, subsequently, of the city, as this is the mother garden that allows the expansion of other similar initiatives, spreading knowledge and seeds.

The project plans to be not just a garden, but a network of gardens, with the constant movement of seedlings, plants, people and knowledge. So far, these seedlings have given rise to two other gardens in different locations: one in the small garden at the health center that serves the region and another in the neighborhood of Marechal Hermes, which was started by one of the project’s apprentices.

There is an important question that arises when we talk about the operation of the garden, which is how to describe the garden and its different agents, seeking to pay due attention to the non-human participants - animals and various plants - in that environment. This concern does not derive from a methodological point alone but also seeks to contemplate the way in which the human creators themselves talk about non-humans participants - treated by them as central agents of this space. Thus, in the garden there is a reference to “collaborators”, the agents who contribute to the garden, whether they are human or not. In view of this, the organization of the garden space is based on the vegetable collaborators. As Niara explains, she is not the one who chooses where the plants are; the plants themselves choose where they will be, because they know which is the best place for them. She also says that she talks to the seeds, listens to what they say and plants them according to the guidelines she receives from them. And she adds: when she does not listen to the plants, the seeds do not sprout - or they struggle to do so. The choice is therefore not Niara’s, but the up to the plants, as she insists.

This posture in relation to the arrangement of the plants is not a question of the plants having taken root, because many of them were still in crates, and not in the ground, and could only be lifted and moved. It does refer to the place where the plant would grow best. Niara’s logic goes against the fixation and determination of spaces by any logic other than the vegetal one.

Challenging traditional logics of spatial organization, the garden space is also organized by purposely seeking to make circulation difficult in some stretches to hide certain species. Although the garden has the purpose of teaching and propagating seedlings, access to plants is not indiscriminate, being moderated to be done in the right way. There is a unique learning method, conducted by Niara do Sol. Niara tries to conduct the pedagogical space of the garden in a fashion consistent with the vision that emphasizes the specificity of each being and the importance that knowledge is practical, both in the acquisition of seedlings by the participants and in its subsequent application. To achieve this purpose, the garden purposely remains entangled and does not have discreet and divided beds as commonly found in other gardens.

In this sense, we present the speech of Dauá Puri, one of the indigenous producers of the garden, about the impact that the project had on the environment of the condominium:

And I’m now here in a facility... which is a facility that’s not so favorable to us, but that’s what the agreement we made with the state government, that’s what they got for us, bringing us here and putting us in an... apartment. So, everyone is tight, but we try to adjust as best we can. (...)

I’m looking and I see an environment, but my heart speaks louder. I can change this environment. I transform this environment into a welcoming environment for me. This is the indigenous soul. We are always looking to work from the perspective of good living. Good living is a good snuggle, a good hammock, a good, pleasant conversation with a nice person, a bonfire... Here (at MCMV), you can’t make a bonfire... but you can make music. We also need to be happy. Because we live in a society of extreme materialism. We need to be satisfied, we need to reframe, see meaning in everything: in the ant, in the bird, in the water, in the wind, in the air. It all makes sense. Even in these rooms of the shelter you have. The reality is that the concept of my people is shelter, not home. You shelter for a season you leave there. I arrive, I am, but I never stay. I’m always prepared to know that suddenly I have to leave. And we need very little to live. We need much more friendly words, the friendly arm, the family, the group, the group you belong to. What they took from the indigenous peoples, by destroying, they did not manage to destroy the fundamental thing, which is the spirit. You cannot do it. Wherever we are, you will always be changing or getting your way. And then how can we make things reach people? It is by taking on this art. Taking this music, showing that it is possible to create instruments, create arts, that it is possible for you to plant, that it is possible to breathe better. (...)

And how can the city become a forest? Like this! (Points around.) I think the experience that Niara brings is this: “No, we can’t, we have to plant!” It’s indigenous. Then we can live better. Because when I got here, the situation in this building was very bad. Sleeping was very bad. And not now: I lie down and look, look at the birds. It’s wonderful. But if there wasn’t the hand of an indigenous woman, our doctor, planting and doing this work, we wouldn’t have this well-being. So the forest is here. You can do it. As she says, plant a tree on your birthday! Or ten, or twenty, or fifty: as many as you like. (...)

So we were placed here. We agreed to come here. And from there we understand that we have a mission here. The example when we arrived here was raw earth, very bad clay. And now we have a passion fruit here (lifts the passion fruit that Niara had just picked and handed to him). It means that I can taste it, so I can sing. So when we arrived it was very difficult, I didn’t breathe well, I didn’t sleep well. Today we breathe, it has changed a lot. (...)

And many things have changed; people began to see and started planting in their homes, improving their entrance to their place, and having a little access to indigenous medicine. So it has changed a lot, and it will change. Because it’s inspiring. And it is to inspire. Indigenous culture is meant to inspire and dominate the planet. Let’s get everyone back to planting, taking care of the land and taking care of themselves. And it will always change. And I think we need to understand that we need to make a difference. And wherever you are, you can make a difference. And you can do it differently. Having determination and knowing that we can be better. Well alive, and fight for our good life. (...) (Puri, 2021)

Dauá presents the concept of shelter from the Puri perspective, which talks about the transitional quality of housing. Despite the denial regarding the permanence in the place and the recognition of the inadequacy of this shelter - where you cannot make a fire -, there is a practical engagement with the surroundings. The land is worked and improved not just for them, but for everyone who is there, and even if in the future they are no longer in this place, they will have left there a new land, a new landscape and new practices.

Dauá points to the ability to transform the surroundings through action, planting, construction, teaching. This is what Dauá presents as the perspective of indigenous good living9, which can inspire the whole world and transform the city into a forest. Throughout his speech, we detect a specific perspective of the landscape as an environment that modifies and is modified by its inhabitants, an environment constructed by both natural and human elements, which are presented in an undifferentiated way. The land, the building, the birds, the neighbors… All are elements of a landscape that is constantly reflected and acted upon.

These planting spaces represent gaps in a housing project that, according to its conception, obstructed adaptation of the housing unit and its surroundings to the needs or wishes of the residents. Moreover, it is based on a design that does not take the land beneath all the concrete into consideration, land as a fruitful element of income and community integration. In this specific case, spaces for creation and cultivation also bring to light the survival of the memory of traditional communities, both related to planting techniques and the affective relationship with the land.

This experience of re-adapting traditional ways of doing things to the urban space is an example of an increasingly accentuated demographic transition in Brazil. We can observe the evolution of indigenous urban territorialities from the census numbers carried out by the IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatisticas (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) in the years 1991 and 2010. In 2010 the survey indicated the existence of 896,9 thousand indigenous people belonging to 305 ethnic groups, among which 324,834 thousand (36%) inhabit urban areas. This is a major contrast to the 1991 IBGE census, in which the total indigenous population was 294,148 thousand, with 71,026 (24%) residing in urban areas. Hence, there was a 304% increase in the total number of self-declared indigenous people and a 457% increase in the number of indigenous people in urban areas10.

4. Between architecture and anthropology

4.1 Dwelling perspective

We propose that the MCMV and the Dja Guata Porã Garden represent different perspectives of dwelling. In order to reflect on these different perspectives that were presented here we call upon authors who seek to think about urban design critically and from the perspective of other cosmologies.

Ingold proposes two different and contrasting concepts: what he calls a building perspective and a dwelling perspective (Ingold, 2000). The perspective of construction - which can be associated with the profession of architects - is characterized by the idea of applying projected shapes to inert matter. From this perspective, there is an exteriority - the world, nature - on which self-contained individuals act based on mental projects.

From a building perspective, human beings are primarily producers; beings who design and carry out projects, transferring mental design to the world, which is seen as a passive and inert externality. From this point of view, humans differentiate themselves from animals because of their intentionality, given that they produce societies and history - thus distinguishing themselves by their transcendence, domestication and capacity to intentionally transform nature.

In the author’s words:

Suffice it to note that the essence of the kind of thought we call ‘Western’ is that it is founded in a claim to the subordination of nature by human powers of reason. Entailed in this claim is a notion of making things as an imprinting of prior conceptual design upon a raw material substrate. Human reason is supposed to provide the form, nature the substance in which it is realized. (Ingold, 2000, p.80)

The dwelling perspective - which we propose is closer to that of the collaborators at Dja Guata Porã Garden - stems from the notion of dwelling and ideas arising from the coexistence of people in that landscape. In this case, projects emerge from the experience of being in the world, and not as isolated forms to be applied to an inert nature. This way, humans are participants in processes of growth and transformation. Taking the cultivation of plants and the raising of animals as an example, it is shown how humans not only produce but also promote suitable conditions for the growth of these species (for example: a farmer does not produce carrots, but creates the necessary conditions for them to grow).

In this perspective, environment is the key space for coexistence, thought and action of those who work there. And it is important to point out that in the garden there is no unilateral human action on nature, but a mutual coexistence, in which both humans and animals are born and grow in environments previously shaped by their predecessors. Based on this idea, Ingold proposes that learning occurs much more in an environmental way.

Shifting to this perspective allows us to think of coevolution in the terms of philosopher Donna Haraway (2015), which takes place in a multispecies landscape. This is because history is the evolution of people and the environment growing together, not the inscription of human history on the materiality of nature.

I have presented, by contrast, human beings do not so much transform the material world as play their part, along with other creatures, in the world’s transformation of itself (…) In this view, nature is not a surface of materiality upon which human history is inscribed; rather history is the process wherein both people and their environments are continually bringing each other into being. (Ingold, 2000, p.87)

The MCMV project views housing as a mere space that can be standardized, produced in scale, disregarding any concern for local contexts, residents’ needs or the urban fabric. In this way, it acts through the building perspective, designing projects regardless of the landscape and applying it nationwide. In its midst, the Dja Guata Porã Garden represents a gap in this logic, re-occupying the space in a way it was never intended and using it for a vegetable garden. Furthermore, thinking about it taking into account other species needs and developing the project gradually, according to the needs of the local landscape. In turn, we argue, this would be the dwelling perspective.

From Ingold’s dwelling perspective, there are no finished objects, but materials and people that continually go through joint processes of transformation. From this point of view, a building will never be finished: it will, instead, be continuously modified, and built by the use of its inhabitants and by the continuous process of transformation of materials over time. Therefore, houses would be like living organisms, and not like fixed and passive objects, being more appropriate to use terms close to ecology to talk about them.

The writer and researcher Stewart Brand (1995) says that this process of transformation through time is “how buildings learn”. This is because, after being built, they are modified, a process in which the infrastructure and space are adapted to the use of its residents. In this way - and just like people - buildings learn and change over time.

From this perspective, Stewart Brand argues that, when designing spaces, architects should take into account the flexibility allowing them to be transformed by their users. That’s because, in most cases, architects’ biggest concern is designing visionary projects that don’t take into account how that space will be used. The result would thus be one in which architecture, as a discipline, would focus more on transformation than on the idea of permanence.

Buildings have lives in time, and those lives are intimately connected with the lives of the people who use them. Buildings come into being at particular moments and in particular circumstances. They change and perhaps grow as the lives of their users change. Eventually - when, for whatever reason, people no longer find them useful - they die. (Brand, 1995, p. 427)

According to the architect cited by Ingold, it is after the end of the work that the real construction process begins - with regard to housing, adjustments and maintenance.

Only then, according to the distinguished Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza, does the serious work of building actually begin, as residents embark on their daily struggle to limit the damage inflicted by invasions of insects and rodents, the rot brought with fungal infestation and the corrosive effects of the elements. Rainwater drips through the roof where the wind has blown off a tile, feeding a mould that threatens to decompose the timbers, the gutters are full of rotten leaves, and if that were not enough, moans Siza, ‘legions of ants invade the thresholds of doors, there are always the dead bodies of birds and mice and cats’ (Siza, 1997, p.47).” (Ingold, 2013, p.48)

Therefore, housing and construction occur as continuous processes, since houses and buildings are never finished because they are always changing due to their uses. This happens even when one tries to avoid this vitality of the buildings as much as possible, as is the case with the MCMV, due to the various rules put in place to try to prevent residents from customizing the buildings and apartments; and thus imposing a general standardization that tends to be circumvented in some way by residents through their everyday uses.

It is argued here that the way of making the Dja Guata Porã Garden developed from Ingold’s dwelling perspective much more than from the building perspective. This contrast is shown in the photographs on Figure 9. The garden develops from Niara’s familiar wisdom, but new plants and uses are being added based on a basic logic: that of the respect for plants, viewed as active builders of that space, rather than a mere passive product.

This way, the use of the MCMV space is in constant transformation, despite attempts at stabilization by the administrative institutions. Demonstrating how buildings often have uses other than those initially designed - we have the garden, which was developed in a residual space, and the windows, used to transport gardening material. With all this, the apartments of the project collaborators become a continuation of the garden and the windows function as a mediation between these spaces.

Dauá and Niara’s apartments, on the ground floor, face the vegetable garden. In practice, the main portal that connects these spaces are the windows, often used - during maintenance activities - for communication and passage of plants and objects between garden participants. In Niara’s apartment there is dirt on the floor, seedlings and equipment everywhere, vegetables germinating, hoes leaning against the walls and piles of cotton to be threshed. Close to the windows are frequently used tools, such as pruning shears, shovels and gloves, which, when passed from the inside out, easily reach the garden.

Still reversing the everyday uses of circulation in the building, the doors - generally made to separate indoor, domestic, private spaces from outdoor, public and collective spaces - in the Vertical Village are normally kept open by a stone on the floor, and a plate which reads: “Do not close the door”.

4.2 Forest and citizenship perspective

As we approach the urban project in which the MCMV program is inserted, and in terms of the difference that Dja Guata Porã Garden brings to this space, it becomes clear that this is not an isolated case but a type of common urban planning in the context of Brazilian cities.

First of all, it is necessary to understand that changes in the territory are not neutral and that the modernizing process in the Latin American context is fundamentally related to a process of territorial coloniality (Tavares, 2019). From this perspective, the occupation of the territory is understood as a civilizing gesture and considers the forest areas as ‘demographic voids’11 and the trees and rivers as ‘natural resources’ of economic interest. Ailton Krenak (2019), an important Brazilian indigenous leader, tells us that, if we are in these conditions today, it is because these were designed and executed over at least five centuries.

If this continent has such a profound history, as attested by the signs left in its ecosystems (the forests, the cerrado, the Atlantic forest, mountains and rivers), it is very likely that profound search - following the steps of the wonderful work presented in the luminous words of Paulo Tavares - could identify the origin of the idea of occupying space so arrogantly, a posture that finds in architecture and urbanism a war tool. (Krenak apud ENTRE, 2019, p.21)

In this context, Krenak points to the discipline of architecture - and, thus, urban planning - as an instrument of this war against nature and, consequently, against the peoples of the forest. According to the Brazilian architect Wellington Cançado (2019), the formation of the Brazilian territory takes place from the logic of the “city opposing the forest, like civilization to barbarism” (Cançado, 2019, p. 21t) or even, as an effect of a “civilizing matrix based fundamentally on devastation of the forest, be it Atlantic, Amazonian or Cerrado”12 (Krenak, 2019 apud Cançado, 2019, p.13).

Reaffirming this perspective, architect Paulo Tavares (2016) points out that the initiative to deforest gigantic areas instead of “building-with”(Lagrou, 2019) is a relationship of dominance between “domesticated versus wild, cultivated versus non-cultivated and artificial versus natural” (Tavares, 2016) in which a relationship of dialectical opposition is contained. This relationship is associated with how we think about what we call design (Tavares, 2016) and resonates directly in the practice of architecture, consequently in urban typologies.

In the Brazilian context, the city of Brasília, the city with the main modern urban project in the country, is an example of this design that Tavares (2016) refers to, projected from the alienation in relation to the land. The concrete city invented in the middle of the cerrado is a model of the narrative of technical progress as dominion over nature. In the words of Lúcio Costa, a Brazilian architect who created the project, the two axes that give rise to the urban design of the city “were born from a primary gesture by someone who marks a place or takes possession of it: two axes crossing each other at right angles, that is, the very sign of the cross.” (Costa apud Berenstein & Junior, 2017, p. 2)

Associated with ideas of technical progress and the purity of the form of its urban design, the construction of this ‘dream’, with all the colonial remnants, silenced everything that was considered backward so that the ‘miracle’ of modernity could happen (Berenstein, 2017). Brasília is, even today, one of the main symbols of urban planning in Brazil.

The way in which urban design relates to nature demonstrates the distance between humans and the natural world. This is because proximity only comes from control and, as already mentioned, from the fundamental opposition between built and free area. Understanding architecture as language, we quote the indigenous leader Davi Kopenawa (2015) when he says that: “the conception of the city is, in this sense, less a particular space and more an ontology” (Kopenawa, 2015 apud Cançado, 2019, p. 37).

Therefore, thinking about spaces from a multispecies perspective presupposes starting from an ontology other than that of modern space: an ontology associated with ideas of collaboration between species. Tavares (2016) speaks of a ‘multispecies urbanism’, in which, if the city is a right, architecture is a kind of ‘advocacy’ for this right, which must take into account non-human forms of life as citizens. In this line, Krenak (2019) draws attention to the way of thinking about the differentiated space that exists between indigenous and non-indigenous people. He shows that indigenous cosmovisions are also linked to their own way of designing villages and dwellings based on observations of celestial bodies and human bodies:

In some cases, this unity matches, reproducing the layout of our physical body. These configurations, which are numerous and very different from each other, imply that an arrangement isn’t just about shelter. They are constellations of habitats co-related with other events having to do with the sun, rain, wind, birds, everything. (Krenak, 2019, p.44)

The rhizomatic landscape that Krenak refers to has the following structure: there is a space that the human collaborator is a part of, but it does not have them as a center, existing before and beyond them. Nature is seen as a ‘singular multiplicity’ (Viveiros de Castro, 2017) that presupposes collaborators of many natures and, with specificities, manifest themselves in different ways. The landscape, as an object of culture, is therefore a mutable entity, not subsidized by types or typologies, but by cultural modifications (Name & Moassab, 2014).

In the Dja Guata Porã Garden, the plant world is central to the culture and, consequently, to the space. In this sense, we can draw parallels between the gap that Dja Guata opens and the fragments of landscape proposed by Clément (2004). According to Clément, there are landscape fragments that are located at the edge of the territory, without defined functions and attributions, operating as refuges for diversity. About these spaces, the author proposes the term Third Landscape. The main difference is that Dja Guata was not born organically, as the fragments that compose the Third Landscape, and was rather the result of a project vision coming from indigenous design. The residual space of the condominium used for the garden could also be seen as a terrain vague, in Solà-Morales’ (1995) term, in the sense of unoccupied, unused urban spaces, that at the same time are full of unlimited possibilities.

In these landscape rhizomes, vegetation is not a homogeneous and static exterior, but a “being” juxtaposed with daily life. This implies changing the idea of environment as an economic resource and placing it as part of a set of collaborators that determine the shape of the space. This is because the forest we see today is often an inheritance of indigenous design, since they interfere in the landscape not in an extractive way but in a collaborative way. There is an exchange relationship. Indigenous botanical technology multiplies the forest’s biodiversity (Clement et al, 2015; Balée, 2013), just as the forest sustains it, both in terms of food and in its spatial, political and metaphysical organization.

The productive and relational dimension that the Dja Guata Porã Garden has with space helps to remove nature from the margins of architectural projects and to bring it into daily life, inserted in an exchange relationship. In the indigenous world, the landscape is not at the margins, it is at the center of the “project” of spaces. It acts as a connector for activities, regenerating the soil, producing food and training the individual as a participant in the processes. Florestania, the right to life of the forest and its peoples, in this case, appears from a fracture in a monotonous, rationalized architectural project that treats the non-sealed soil as areas of leftovers between units.

5. Conclusion

This article sought to present Dja Guata Porã Garden, an urban horticulture project carried out by indigenous residents of the Vertical Village, in Rio de Janeiro. As shown, the garden is located inside an MCMV condominium. We present the MCMV and the existing criticisms to the execution of this project so far, regarding the lack of planning and connection with the urban environment. After that, we presented Dja Guata Porã Garden and introduced the way of doing of its indigenous coordinators.

From this ethnographic case and its contrast with the MCMV, we then turned to authors who discuss the decolonization of architecture and urbanism. Also about different forms of dwelling. A unique urban horticulture project can thus be seen as a gap between the urban fabric that is designed from a generic perspective of space. This is because it creates new urban realities in a once colonized soil, recovering traditional and indigenous logics and practices. In this case, we argue that the exception can clarify the rule being produced in social housing design. The action of creating new urban realities from gaps not only opens breaches in the condominium soil but also takes over a territory that was originally indigenous.

The Brazilian territory has indigenous roots that, during the colonial period, were erased. And these gaps expose two opportunities: the resumption of indigenous memory through the territory as an ancestral space and better environmental management of the city, with the ideas of preservation and environmental management of traditional peoples playing the role of interlocutors. That is, the perspective on a type of multispecies urban planning, which begins with a territorial policy that does not hierarchize man and his plant collaborators. These territories formed from other ontologies tell us about other possible worlds. Futures that, through original ontologies, become present, even if they are hidden from architectural design manuals.