Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Medievalista

versão On-line ISSN 1646-740X

Medievalista no.29 Lisboa jan. 2021

https://doi.org/10.4000/medievalista.3902

DOSSIER

Medieval naturalia: identification, iconography, and iconology of natural objects in the late middle ages

Naturalia medieval: identificação, iconografia e iconologia de objetos naturais no final da idade media

Chantal Stein1

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1091-4039

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1091-4039

1The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Objects Conservation Department, 10028, New York, USA, chantal.stein@metmuseum.org

ABSTRACT

The nascent global age at the close of the Middle Ages introduced exotic objects from distant lands into Western Europe. Exotica from the natural world - naturalia - were frequently fashioned into ecclesiastical and seigniorial artifacts and housed in treasuries. The materials were sometimes re-identified in their new contexts, such as narwhal tusks understood as unicorn horns, which bestowed upon them additional meanings associated with those allegorical mythical creatures. This work investigates the movement, alteration, and use of such re-identified naturalia in late medieval society leading up to the Age of Discovery. It focuses on naturalia that retained their distinct morphological features after working, following the hypothesis that the identity of the animal, as indexed by a recognizable form or set of physical characteristics, was important. It additionally considers symbolic connotations and occult properties deriving from allegorization of matter to study the role played by the ornamentation of naturalia. This paper explores the discourse between extant tangible objects and contemporary texts such as bestiaries, lapidaries, and alchemical compendia to examine how the iconography of the artifact’s form and the iconology of the ornamentation contributed to the overall signification of the naturalia.

Keywords: Naturalia; Exotica; Animals, Unicorn; Treasuries.

RESUMO

A era global nascente no final da Idade Média introduziu objetos exóticos de terras distantes na Europa Ocidental. Os objectos exóticos do mundo natural - naturalia - foram frequentemente modelados em artefactos eclesiásticos e senhoriais e guardados em tesouros. Não raras vezes, esses materiais eram renomeados no novo contexto - como presas de narval, entendidas como chifres de unicórnio - recebendo significados adicionais associados a criaturas míticas alegóricas. Este artigo investiga o movimento, alteração e uso de naturalia renomeada, no contexto da sociedade do final da Idade Média. Foca-se em objectos que mantiveram as respectivas características morfológicas distintivas depois do seu funcionamento, a partir da hipótese de que a identidade do animal, indexada a partir de uma forma reconhecível ou conjunto de características físicas, era importante. Além disso, serão ainda consideradas as conotações simbólicas e propriedades ocultas decorrentes da alegorização da matéria para estudar o papel desempenhado pela ornamentação de naturalia. Este texto explora o discurso entre objetos tangíveis existentes e textos contemporâneos, como bestiários, lapidários e compêndios alquímicos, para examinar como a iconografia da forma do artecfato e a iconologia da ornamentação contribuíram para a significação geral de naturalia.

Palavras-chave: Naturalia; Exótica; Animais; Unicórnio; Tesouros.

Introduction

Though the European Age of Discovery is credited to the 15th century’s expanding trade, travel, and exploration, the global movement’s roots stretch back three centuries earlier to a time when many distant lands were still unfamiliar to each other. In this nascent global age, discovery and exploration of hitherto unknown worlds fostered a taste for exotic wonders and marvels and introduced exotica from distant lands to Western Europe. Exotica - all material coming from far away - were associated with regions at or beyond the edges of Christendom and carried with them the sense of contact with an unknown world. As a subset of exotica, naturalia consisted of natural objects (as opposed to man-made artificialia) that were often fashioned into ecclesiastical and seigniorial artifacts and kept in treasuries, forming a small but highly valued part of material culture[1]. Though originating from real animals, naturalia were often re-identified and considered as evidence of other mythical creatures found in medieval bestiaries; narwhal tusks, for example, were identified as unicorn horns.

Many scholars have previously discussed exotica in the context of the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery[2]. However, few have examined such artifacts in earlier medieval contexts, and even fewer have considered their materiality, significance, and embellishment. This work aims to answer questions about the movement, alteration, and use of such re-identified naturalia in late medieval society leading up to the Age of Discovery. It will focus on naturalia that retained their distinct morphological features after working, following the hypothesis that the identity of the animal, as indexed by a recognizable form or set of physical characteristics, was important. The study explores the discourse between extant tangible objects and contemporary texts such as bestiaries, lapidaries, and alchemical compendia to examine how the iconography of the artifact’s form and the iconology of the embellishment materials contributed to the signification of the naturalia[3].

Wonder and natural allegories

In the late Middle Ages, the steadily growing European economy allowed for more frequent and more far-reaching exploration, and Europeans traveled in greater numbers than before in search of wealth, trade, and opportunities for evangelicalism. Missionaries and other frequent travelers wrote for readers at home about the novel locales, strange peoples and creatures they encountered, and the wonders and marvels found abroad. As the world and all its marvels were considered revelations of God’s divine spirit, the emotion of wonder was seen as a precursor to divine contemplation. Expressed by Thomas of Cantimpré, the Christian’s duty was to “wonder at creation and, by extension, at its Creator”[4]. The natural world was considered a divine, external manifestation of God’s invisible nature and eternal realm, and contemporary philosophers interpreted the visible universe allegorically; the natural world became a signifier for hidden spiritual truths, and natural wonders were used as religious edifying metaphors in medieval encyclopedias. Like all else in the natural world, animals were rooted in God’s work, and so they existed in the medieval mindset largely as constructs for allegorical ends[5]. The emphasis on moral edification superseded interest in fact, making accuracy - or even the existence of an animal - of less concern than the animal’s usefulness for didactic purposes[6]. In medieval bestiaries, entries for each animal comprised two parts: the first provided natural history facts on habitat, physical characteristics, and the etymology of name, while the second interpreted the facts symbolically to provide the reader with moral lessons.

As depicted in bestiaries, fantastic creatures were always found in other lands at the far corners of the world. By the late Middle Ages a spherical understanding of the world had developed. The oikoumene - the habitable portion at the center that formed the setting for the fall and salvation of mankind - was seen as a landmass that occupied a discrete section of the globe, comprising Western Europe, the Mediterranean basin, and the Holy Land. The fines terrae - the extreme outlying yet settled edges of the known world - consisted of India in the east, Ethiopia in the South, the Pillars of Hercules in the west, and the Orkneys and Iceland in the north. Fantastic creatures and terrific monsters were believed to live in the fines terrae, guarding the borders against the terra incognita - the chaos beyond[7]. The margins of the known world were places of novelty and variety where wonders tended to cluster, and the native animals were rare and mysterious[8]. Such exotic creatures were introduced to medieval Europe through moralizing bestiaries, natural history compendia, travelers’ tales, noble menageries, and tangible naturalia. Without regular trade, these margins occupied a space almost entirely disconnected from Europe, which lent credence to the existence of creatures outside of daily life.

Re-identification and iconography of form

When naturalia reached Western Europe, the real animal parts substituted for and acted as evidence of the mythical creatures believed to exist in distant lands. For example, narwhal tusks were reconceived as unicorn horns. Narwhals are rare arctic whales whose largest population, and likely the primary source for medieval western markets, is located in the waters around Greenland such as Baffin Bay and Kane Basin. Though the extent of medieval whaling is difficult to gauge, it was likely infrequent and dangerous. Advances in shipbuilding led to increased Scandinavian trade, travel, and exploration, with Europe’s earliest expansion reaching into the North Atlantic. It is therefore possible that narwhal tusks were provided by Vikings, though Plukowski suggests they were more likely acquired from native Inuit[9].

Narwhal tusks were brought to northern Europe, specifically Denmark and Holland, via shipping routes connecting Greenland and Iceland with the British Isles, Scandinavia, and the Baltic[10]. Though it didn’t amount to a regular commerce until the 16th century, trade was established as early as the 12th century and possibly earlier. However, the extent of trade is unclear, as comparatively few records were kept during this time period. Additionally, since narwhal tusks belonged to a business founded on mistaken identities, those concerned may not have wanted the true source of unicorn horns - often referred to as alicorns in scholarly literature - revealed. By the 17th century sellers were intentionally deceitful, but Shepard suggests that in earlier centuries that the whalers may not have known how the tusks were being marketed and those conducting the final sales may not have been aware of the tusks’ origins[11]. The rarity of narwhals explains why so few tusks reached Western Europe despite the high demand and why their true sources were shrouded in mystery.

In another example, supposed griffin claws - Greifenklauen in German - were fashioned from the horns of Bovidae species such as ibex, buffalo, ox, auroch, and bison[12]. Most of these species could be found in central and eastern Europe at the time[13]. In addition to griffin claws, contemporary inventories also list drinking horns that, though fashioned from horns of comparable species, do not seem to have been mistaken as griffin claws. It remains unclear why some horns were recognized as horns and others were re-identified as griffin claws; perhaps they were distinguished based on their status as either local or exotic items, as some of these animal species are also found across parts of Asia.

Ostrich eggs held their own value, but they were occasionally re-identified as griffin eggs and fashioned into drinking cups known as gripesey. Though ostriches had been known since Antiquity, in the Middle Ages their eggs were still very rare and most knowledge of them came from bestiaries and other depictions rather than observation of real birds[14]. The routes by which these birds and their eggs came to Europe are not well known; eggs could have been produced by captive ostriches in noble menageries or may have been traded from Africa or the Arabian Peninsula. Wild Asian ostriches survived in the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula until they were hunted to extinction in the early 20th century. Though African eggs may also have reached Europe via Arab trading posts in East Africa, Green and Guérin both argue for alternate trade routes from Africa directly north to the Mediterranean[15].

Removing an object from its original context allows it to be reinvented. Re-identification of an animal, whether intentional relabeling or unintentional misidentification, allowed it to take on the properties, values, and meanings of the allegorical mythical creature with which it was associated. This type of misidentification was possible because medieval thinking, as expressed by Albertus Magnus, divided animals into discrete parts of physical forms, and comparisons of animals focused on the presence and configuration of such parts[16]. In medieval art in particular, figures and animals had recognizable physical features or diagnostic characteristics that allowed for their identification. As much medieval art was intended to teach and inspire, narrative clarity was paramount and so repetition of forms in art, like a type of visual shorthand, helped viewers identify subjects and concepts more easily[17]. When diagnostic characteristics in art were similar to physical parts found on other animals, such as the long spiraled form of the unicorn horn and the long spiraled tusk of the narwhal, it was easy to associate one with the other.

Diagnostic features of mythical creatures were usually known from bestiary illustrations. The unicorn was considered a fierce creature that could only be caught when first lulled into a false sense of security by a maiden and then taken by hunters. This virgin-capture story was syncretized into Christian metaphor and almost all bestiaries depict it. The story overall represents the birth, life, and death of Christ in one compact, compressed narrative, where the unicorn is emblematic of Christ’s invincibility and humility, the virgin represents the Virgin Mary, and the huntsman symbolizes the Holy Spirit acting through the Angel Gabriel[18].

The horn is the unicorn’s most diagnostic feature, associated with divine force and likened to the unity of Father and Son[19]. The alicorn is always depicted as long, tapering, and often with a diagnostic spiral twist. One of the most interesting aspects of the history of the unicorn is the persistent belief in the natural spiral twist of its horn, first mentioned by Aeliean in the 3rd century: “Between its brows there stands a single black horn, not smooth but with certain natural rings, and tapering to a very sharp point”[20]. Early descriptions and depictions of unicorn horns varied, ranging from black to white, to white with black bark, to polychrome. The characteristic white ivory color and spiral twist began to appear in medieval art in the 12th century was subsequently delineated in almost every medieval bestiary until it became an established iconographic motif by the 14th century. Certain scholars suggest that Christians may have remodeled the form of the unicorn horn in response to the trade of narwhal tusks[21]. Spiral contours were linked to a wider pictorial lexicon of religious structures and objects and may have functioned as signifiers of sanctity[22].

An equally complex allegorical interpretation belongs to the griffin, a quadruped with the body of a lion and the wings and head of an eagle. Griffins were believed to guard the Hyperborea, the legendary land around the distant North Pole that was considered the center point around which the heavenly spheres rotate. The land was supposedly plentiful with gold, marking it as the gateway to the spiritual world. As a two-natured, double animal, the griffin embodied the dual nature of man[23]. Griffin claws held their own legend: a medieval tale records how Saint Cornelius once cured a griffin of epilepsy and was given a claw in return, leading to a medieval belief that only men with powerful and holy qualities could possess such an object[24]. Ostrich eggs were also occasionally identified as griffin eggs. The diagnostic features of griffin claws or eggs are not discussed in texts; when seen as extant objects, however, the animal horns that stand in for griffin claws are always large, slightly curved and tapering to a sharp point, and are naturally colored a shade of red, brown, or grey-black, visually similar to the claws seen in bestiary illustrations of griffins. Significantly larger than eggs from Western European birds or reptiles, griffin eggs would have been immediately noteworthy for their size.

Embellishment and iconology of materials

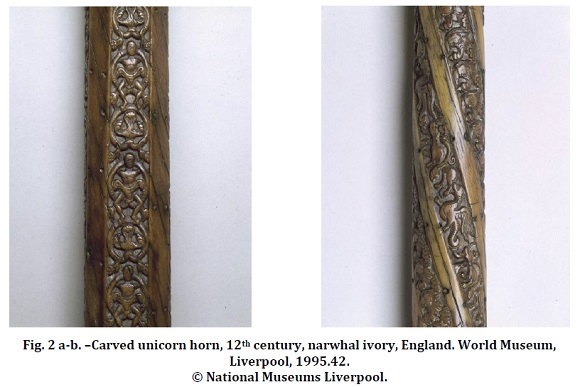

Even when modified by artisans, naturalia often maintained the diagnostic morphological characteristics required for their identification. For example, alicorns maintained their defining spiral twist even when carved, such as those referenced in the inventories of the Lincoln Cathedral in England and the San Marco Basilica in Venice, among others. Rather than just maintaining, carving could also emphasize the naturalia’s defining characteristics. Consider the carved tusks from the Lincoln Cathedral, one now at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London (Fig. 1a-c) and one at the World Museum in Liverpool (Fig. 2a-b), which are both elaborately and variably carved in sections. The Victoria & Albert Museum alicorn contains two alternating designs on the lower section: one portrays repeating naked human figures reaching up to grasp the tails of beasts (Fig. 1b), while the other depicts repeating dragons and animals (Fig. 1c). The World Museum alicorn contains similar alternating designs on its lower section: one illustrates naked human figures in foliage (Fig. 2a), while the other portrays figures with profile heads. For the upper sections, the Victoria & Albert Museum alicorn alternates bands of plain leaf scrolls and bands of birds and animals in foliage (Fig. 1d), while the World Museum alicorn intersperses bands of similar plain leaf scrolls and bands of dragons chasing animals (Fig. 2b). Both alicorns contain pinholes on the plain un-carved surfaces that suggest these areas were originally covered with metal strips. The undecorated strips between the lower and upper sections were probably covered with metal bands to facilitate handling[25]. Though not identical, the similarities in decoration between the two horns have led scholars to believe they were produced in the same workshop.

Medieval ornamentation, such as these carved designs, functioned as a mechanism for guiding the viewer’s encounter with an object; it acted as a mediator and a point of orientation from which the viewer could engage with and form a connection with an object[26]. The carving and the metallic enhancement of the bands both followed the natural spiral of the tusk to visually enhance the spiral twist itself and render the twist more apparent. This type of tautological alteration doubled what was already there, enhancing the alicorn’s visual impact and reinforcing its identity as unicorn and association with related unicorn symbolism[27]. Traditionally, especially from the 12th century onwards, foliate decoration has been interpreted as a reference to revival and renewal in the context of the church reform. Weinryb and Zink both argue for an alternate interpretation, linking foliage with primordial matter and Creation, where all plant motifs - trees, foliage, branches, and so on -represent a “hymn to Creation”[28]. The symbolism of these carved designs was added to the symbolism of the alicorn’s form, resulting in an accumulation of meaning: once carved, these alicorns no longer referenced just the unicorn but also all of Creation.

Naturalia were often further embellished with additional materials such as metals and gems. This type of adornment added a support, similar to the function of frames for paintings or reliquaries for relics, that followed a principle of analogy wherein valuable relics or religious objects were decorated with similarly precious materials. The elaborate mounts also created glittering surfaces that captured the viewer’s gaze, demanded attention, and granted the objects maximum visual importance, bestowing honor upon them and conditioning their reception by viewers[29].

Both natural and artificial materials had strong symbolic connotations. Aristotle’s doctrine of hylomorphism, which was highly influential in the development of medieval philosophy, contends that every physical object is a compound of matter and form, which are intimately intertwined[30]. In addition to the iconography of form, material itself held meaning in what Weinryb refers to as the “allegorization of matter:” an object’s meaning could be enhanced by the signification of its material, which was understood through a network of texts. Materials did not have to represent something pictorial; they could convey in tangible form through their presence alone a metaphoric and intangible concept such as divinity[31]. Materials were also attributed occult properties: as declared by Marbodus, materials held powers, vitalism, and agency that came from the physical matter itself, independent of form and appearance[32]. To that end, the materials used to embellish naturalia could be as metaphorically significant as the naturalia itself.

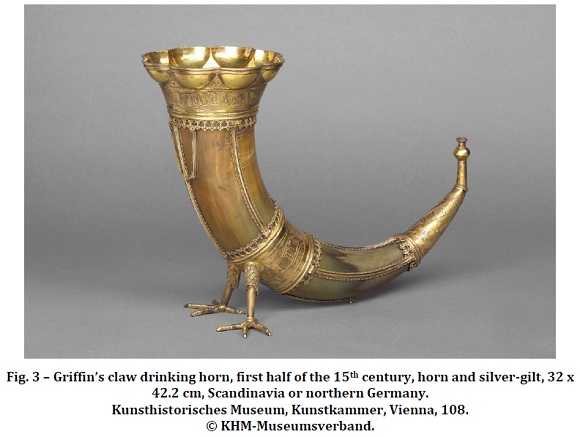

Griffin claws and eggs, as described in inventories of noblemen, were often decorated with silver or gold, such as an egg from the Residenz München in Munich that contains a mount, a spiral cap, and hanging chains in silver-gilt. A griffin claw goblet at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna consists of a curved, tapering horn that is decorated with strips of gilded silver, a large gilded rim encircling the opening, and a smaller ring encircling the tip. In between are two gilded bands, out of which emerge floral and foliate gilded feet on which the claw can rest. Another griffin claw from the Kunsthistorisches Museum emphasizes its griffin origins: though similar in appearance with silver gilded bands and strips, the mouth is lobed and the feet are shaped like those of a clawed eagle (Fig. 3).

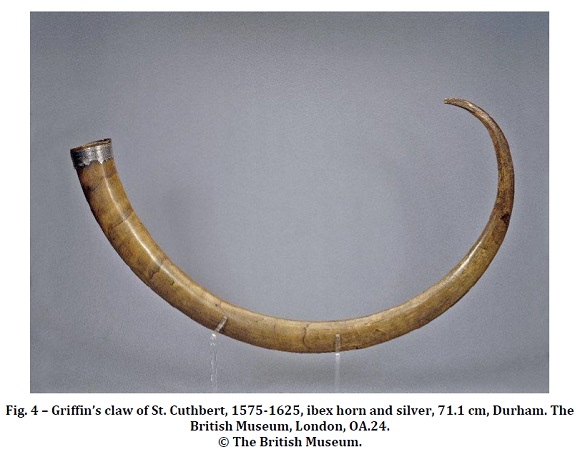

Since animal parts cannot easily be dated, naturalia are often dated instead by the style of their mounts. However, almost all extant mounts and fittings are later than the natural objects and usually replace previous fittings. For naturalia with strong provenance information, evidence of previous fittings can sometimes be gleaned from inventory descriptions; for example, the alicorn from Saint-Denis, now at the Musée de Cluny in Paris, is currently undecorated but has a history of various embellishments, including a medieval mount of silver[33]. Mounts and fittings were also used to ensure authenticity by providing fields for inscriptions, like the silver rim on the griffin’s claw of St. Cuthbert (Fig. 4). Though this decoration is dated to the sixteenth century, for the purposes of this discussion it can act as a representative for earlier silver ornamentation referenced in medieval inventories. The silver rim around the opening contains an inscription that reads GRYPHI UNGUIS DIVO CUTHBERTO DUNELMENSI SACER (“The claw of a griffin sacred to the blessed Cuthbert of Durham”), associating the claw with the popular Anglo-Saxon Saint Cuthbert and suggesting he was the holy man that received this claw after curing a griffin[34].

Gold was considered a perfect substance that nature always strived towards, as it doesn’t rust. A material analogy was made between gold refined in a furnace and souls purified by suffering: only those as noble, pure, and wise as gold could pass through the world - the furnace - to enter heaven unchanged[35]. Gold’s earthly immutability suggested a heavenly permanence and its essence was believed to transcend its terrestrial nature. Correspondingly, medieval artists reserved gold for the divine and used it as a metaphor for heaven. Though few medieval examples are extant, gold was used to decorate alicorns. When used to adorn griffin claws, gold perhaps referenced and reinforced the griffin’s status as a guardian of gold and the gateway to the spiritual world.

Silver was considered only slightly less pure than gold and represented Christ’s human nature rather than divinity. Under Gregory the Great’s assertion that God was able to communicate via physical objects, silver acted as an eloquent transmitter and mediator between God and man[36]. In addition to the materiality, Thomas of Cantimpré allegorizes the refinement of silver as symbolic of the purging of sin, and the forming into shape as representative of the search for meaning through Scripture. Silver’s instability and tendency to corrode was also put to metaphoric use, so that polishing black tarnished silver back to a white metal was considered analogous to the original votive act of purifying silver[37]. Therefore, while not representative of the divine, silver ornamentation still provided a means through which humans could show their devotion to and interact with the spiritual world. As in Scripture, silver was often paired with gold and this pairing, according to Kessler, represented “divine radiance”[38]. The combination of the divinity of gold and humanity of silver may have represented a fuller picture of human interaction with and veneration of divinity.

Symbolic efficacy: ecclesiastical and seigniorial treasuries

Great collections that housed such items were the monopoly of wealthy religious foundations and monarchs. Most were created by generations of accumulation; Pomian refers to them as “collections without collectors” because they were the works of dynasties and institutions rather than individuals[39]. These medieval treasuries functioned as repositories of both spiritual and economic wealth, and contained objects that could be displayed or even sold as needed for income. The church and state maintained a constant exchange of signs and insignia of power through the medieval practice of gifting materials and relics[40]. Lugli’s concept of “reciprocal permeability” allowed for an object invested with symbolic meaning to migrate between contexts, so sacred objects could be secularized and secular objects could be rendered sacred. This type of dual exchange identified religion with power and vice versa: possession of powerful sacred objects granted credence to the manifestation of divinity within the ruler and granted power to the church[41].

Bringing natural artifacts into ecclesiastical and seigniorial collections conserved the sacredness and power of the naturalia and brought them into the known and familiar contexts of the cathedral and court[42]. In tandem, possession of wonders represented and partly constituted wealth and power; in a literal sense natural objects were believed to hold occult properties and powers that could be wielded by their owners and, on a more abstract level, the rarity and uniqueness of the exotica reflected that of the owner’s nobility. European rulers began using symbolic marvels to reinforce social, political, and religious hierarchies. Wonders were put on courtly display in symbolic spectacles of reign and political propaganda to delight, impress, and visually manifest power[43]. Naturalia affirmed the ruler’s right to rule and were manipulated as part of this pageantry of power, for example griffin claws used as luxurious drinking vessels at banquets.

In ecclesiastical collections, precious objects were frequently housed with relics in chapels and shrines and would have been visible only to princes, nobles, and benefactors of the abbeys. They would have been temporarily made visible to laypeople when they were brought out and displayed for ceremonial occasions. Limiting exposure protected the objects from theft and magical depletion, and restricting access emphasized their rarity and guaranteed continued feelings of wonder. Less precious natural wonders, with fewer divine associations, magical properties, and monetary value, remained on permanent display. More readily available and less expensive than alicorns, griffin claws and eggs were staples and persistent favorites for medieval collections and were frequently displayed in highly elevated locations[44].

Designed to display the wealth, power, and devotion of their owners, most items in medieval collections were ostentatiously decorated. Theophilus emphasized embellishment as a way to revere God: “God delights in embellishment of this kind [with gold, silver, brass, precious stones, and wood] and in universal craftsmanship”[45]. He describes rich and marvelous adornments as appropriate and even required in sacred places of worship, arguing that it would be inappropriate not to use the most precious and beautiful materials for worshipping God. Such ornamenta ecclesiae - beautification of the church - was a means for seeking spiritual credit[46]. Suger also regarded beautiful art as a means of inspiring devotion through fine craftsmanship and luxurious materials, where brilliant ornamentation could lead the viewer to contemplating the “heavenly light of God.”[47] Precious mounts were accordingly made of highly reflective and glittering material that referenced eternal light, engendered wonder, and allowed recognition of divine presence in these objects[48]. To that end, churches were accustomed to setting the naturalia with appropriate opulence in gold, silver, and gems. Even while the mounts partially obscured the actual natural objects, they reinforced the power and sanctity of the naturalia.

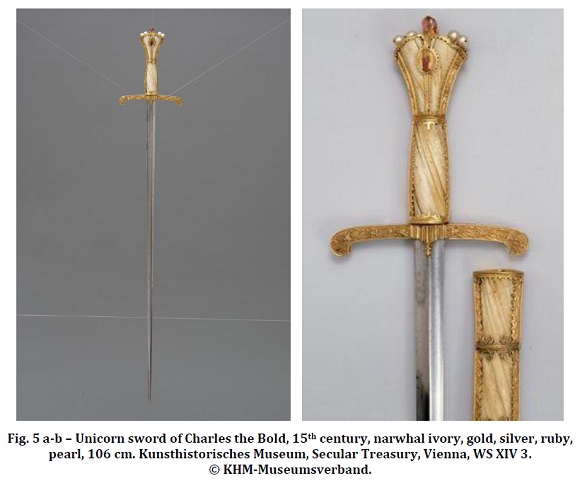

Unicorns were associated with royalty and the right to rule, a belief that dates back to Antiquity. In the virgin-capture allegory, the hunters hand the unicorn’s body over to the king, representing God, for the collective good of the people. To that end, alicorns were highly desired as symbols of a sovereign’s right to rule, and were therefore incorporated into royal regalia such as the unicorn sword of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (Fig. 5a). The long steel sword has a hilt, pommel, and scabbard that incorporate plates of narwhal tusk (Fig. 5b). Though the tusk is only incorporated in small fragments and the overall long, tapering form of the alicorn has been lost, these small fragments still visibly maintain the characteristic spiral ridges that identify them as “unicorn.” The sword’s hilt is decorated with discrete areas of gold overall and with rubies and pearls on the pommel.

Important commodities in trade, gems were often used in combination with precious metals to decorate exotic artifacts. By the late 12th century, bestiaries were frequently bound with lapidaries and herbals as related genres that altogether existed as part of a larger cosmological system representing God’s creation[49]. Like precious metals, gems were valued for their rarity and beauty along with their metaphorical significance and occult properties. Their most conspicuous properties were healing powers, as stones could supposedly correct imbalances in bodily humors and act prophylactically by protecting the wearer from specific diseases. Like many things in the medieval concept of nature, stones were moralized so that each gem contained Scriptural associations corresponding to Christian virtues, which allowed gems to serve as mediating objects linking the earthly and heavenly realms[50].

While overall ornamentation would have served to display the wealth of the owner, specific gems may have been chosen for their attributed properties. According to contemporary lapidaries, all shaped and engraved stones were associated with Mercury and intelligence. All dark red stones were associated with Mars and power, along with the sun and royalty. Rubies were said to contain the main principal virtues of all stones and were accordingly considered the “kings” of gems[51]. Combining all possible meanings, rubies therefore visually reinforced the intelligence, power, and royalty of their owners. Also found on this sword are pearls, which were primarily valued for their ornamental qualities. More than just ornamental, however, pearls were supposedly conceived virginally from the marriage of heaven and earth and were associated with Venus and fertility[52]. In addition to aesthetics reasons, pearls may have been used to link the owner with the desired quality of fertility/virility. Overall, the glittering effect of the crystalline rubies and iridescent pearls would have added to the reflective quality of the metallic gold, enhancing the impression of light and luster.

Materials’ specific virtues could augment or couple to other materials’ virtues. For example, the purity of pearls and purity of gold could mutually reinforce each other; or, as indicated in lapidaries, a ruby’s precious nature could only be truly honored when mounted in precious gold. However, while gems had particular meanings, these were not always clear, precisely definable, or even static, as ambivalent and polyvalent meanings varied with context and could fluctuate between an array of potential meanings. In the medieval context, a thing (res) referred to the sum of all possible insights established at the thing’s creation (significatio). Only differentiated between this polyvalent potential of a thing to signify and specific allegories that were selected for emphasis in certain contexts[53]. With regards to this sword, then, certain allegories of matter could be drawn out (the royalty of rubies, the fertility of pearls) that might be irrelevant elsewhere, such as in liturgical objects. Materials had the ability to oscillate between multiple possible meanings. Combining numerous materials with various metaphors could result in an accumulation of meanings, a type of “symbolic thickening” that broadened the interpretation of the object and increased its symbolic efficacy[54].

Functional efficacy: poison and épreuves

Materials with supposed medicinal or alexipharmic properties were likely intended to be actually functional rather than purely symbolic. The 14th-16th centuries saw the rise of poison as a tool of social and political ambition, engendering rampant fear in the courts, and épreuves - testing agents - were commonly used to detect the presence of and/or neutralize poisons.

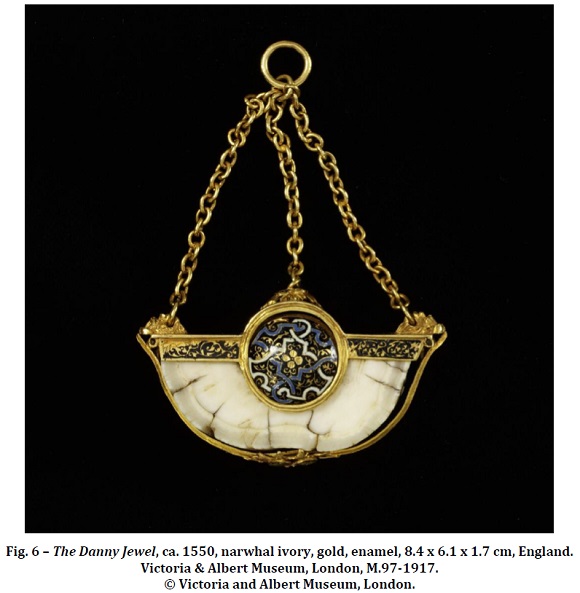

One of the most well-known examples of épreuves is the alicorn. A widespread belief in the alexipharmic and prophylactic qualities of the alicorn, already well established in Europe by the 14th century, was tied to the second most famous unicorn tale from bestiaries, that of the water-conning. In this story, animals refuse to drink from a body of water that has been poisoned by a serpent until the unicorn arrives and makes a sign of the cross with its horn before dipping it into the water, thus rendering the poison harmless[55]. Alicorns supposedly functioned as poisoned detectors by sweating in the presence of poison, and were sometimes thought to neutralize and/or cure poison and other ills. They were used as part of courtly table culture, either set near the food and watched for changes in appearance or, more commonly, touched to the food and drink before a meal began, and they became so popular that they eventually superseded the official taster at aristocratic tables[56]. Often an entire alicorn was kept on the table, though sometimes fragments were fitted into tableware, carved and assembled into beakers, or worn as amulets. So-called healing pots consisted of a bowl, usually made of gold, to which a fragment of alicorn, in the form of a pendant on a chain, was dipped. Bowls are known from numerous inventories though none appear to be extant. One extant Elizabethan pendant, however, may have functioned either as part of a healing pot or as a protective amulet[57]. The Danny Jewel (Fig. 6) consists of a cross-section of a narwhal tusk, cut in half to form a semicircular pendant shape that suggests it was possibly dipped into liquids. Set in an enameled gold mount and suspended from a ring by three gold chains, the cross-sectional tusk fragment maintains a scalloped outer edge, indicating the ridges of a spiral twist and identifying the fragment as alicorn. The back is marked by scratches, most likely made for the production of medicinal unicorn powder[58].

Other épreuves included griffin claws, used as drinking vessels, and serpents’ tongues. Many varieties of serpents found in bestiaries were believed to bite with their tongues to spread the venom that ran through their veins. Serpents’ tongues, known as glossopetrae or tongue-stones, were actually fossilized sharks’ teeth. The fossilized teeth were distinguished for their shiny enameled surfaces, which were often stained by minerals to give a variety of hues from white, yellow, blue, gray, to green. Though shaped like the teeth of contemporary sharks, these fossilized teeth were much larger. It is unclear whether these shark teeth were considered to hold the same properties as snake tongues or were actually misidentified as tongues from snakes. The identification of sharks’ teeth with serpents’ tongues could be explained by visual association alone, but most likely also had a basis in biblical lore: these fossilized sharks’ teeth came primarily from Malta, the location where Saint Paul was bitten on the hand by an adder without coming to any harm[59].

Serpents’ tongues were often suspended in numerous quantities from elaborate dining-table ornaments in the form of golden trees, known as languiers, Natterzungenbaume, or tongue-stands. The earliest references to tongue-stands are found in inventories from 1266 and they reached their height of popularity in the 14th and 15th centuries. Today they are extremely rare and only three extant ones are known, although there are a few individually mounted teeth that may have hung on similar tongue-stands or may have been worn as amulets. A tongue-stand in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna is constructed from gilded silver with a knob of foliage near the top from which tongues spring outwards like a bouquet topped with a large quartz stone (Fig. 7). Part of the crowning bouquet can be removed by lifting the stone, which allowed the tongues to be dipped into wine or food[60]. For naturalia intended to be functional, their ornamentation materials were often believed to hold related occult properties. For example, épreuves were frequently mounted with other supposed healing stones. As described in lapidaries, all crystalline white-ish stones - such as the quartz on this tongue-stand - were associated with Jupiter and safety from fatal illnesses[61]. Here, both the naturalia and the ornamentation were considered alexipharmic, doubling the object’s power.

Though the occult powers of épreuves were seldom questioned, opinions varied over how they worked. Medieval medicine and magic were founded on notions of “sympathy” and “antipathy” and there were proponents of both theories. Theories in favor of sympathy posit that detectors and cures are similar to poisons and so could overpower those poisons. Theories in favor of antipathy suggest that detectors and cures were holy and pure enough to neutralize poisons[62]. Ornamenting poison detectors and cures with similarly alexipharmic or healing materials was perhaps a type of sympathy, reinforcing the power of one material through contact and association with another sympathetic material.

Naturalia and artificialia

Overall, ornamentation augmented the reception of exotica, where artifice worked to support nature by enhancing and highlighting the naturalia. The status of these objects as marvels ultimately derived not only from their presence but also how they were presented. The artisanship of the ornamentation became increasingly valued into the Renaissance, progressively intertwining the wonders of art and nature until eventually the most wondrous objects were those that fused the two together and blurred their boundaries. The naturalia in medieval ecclesiastical and seigniorial treasuries formed part of the earliest curiosity cabinets, situated between the end of the Gothic period and the beginning of the Age of Discovery, as antecedents to the immediately following Wunderkammern. Over time, many of these collections changed ownership, scope, and character, shifting from an ostentatious display to an encyclopedic desire to possess and understand those things that are beautiful in art and nature. By the Age of Discovery, artificialia and the achievements of artists were as highly valued as naturalia and the understanding of nature[63].

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sources

MAGNUS, Albertus - On Animals: A Medieval Summa Zoologica. Translated and annotated by Kenneth F. Kitchell Jr. and Irven Michael Resnick. Volume 1. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. [ Links ]

THEOPHILUS - On Divers Arts. Translated by John Hawthorne and Cyril Stanley Smith. New York: Dover Publications, 1979. [ Links ]

Studies

AINSWORTH, Thomas - “Form vs. Matter”. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [Online]. Spring 2016. ZELTA, Edward N. (Ed.) [Accessed 7 February 2018]. Available at https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/form-matter/. [ Links ]

BENTON, Janetta Rebold - The Medieval Menagerie: Animals in the Art of the Middle Ages. New York: Abbeville Press, 1992. [ Links ]

BOEHM, Barbara Drake; HOLCOMB, Melanie - “Animals in Medieval Art”. in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. [Online]. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000-, last edited January 2012. [Accessed 14 March 2018]. Available at http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/best/hd_best.htm. [ Links ]

BONNE, Jean-Claude - “De l’ornement dans l’art médiéval: VIIe-XIIe siècle; le modèle insulaire”. in BASCHET, Jérôme; SCHMITT, Jean-Claude (Eds.) - L’image: fonctions et usages des images dans l’Occident médiéval; actes du 6e International Workshop on Medieval Societies, Centro Ettore Majorana (Erice, Sicile, 17-23 octobre 1992). Paris: Léopard d’Or, 1996, pp. 207-249. [ Links ]

BONNE, Jean-Claude - “Entre l’image et la matière: la choséité du sacré en Occident”. in SANSTERRE, Jean-Marie; SCHMITT, Jean-Claude (Eds.) - Les images dans les sociétés médiévales: pour une histoire comparée. Bulletin de l’Institut Historique belge de Rome 69 (1999), pp. 77-111. [ Links ]

BRITISH MUSEUM - “Animal Remains.” [Online]. [Accessed 14 February 2018]. Available at http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=44328&partId=1&people=46119&peoA=46119-1-8&page=1. [ Links ]

BUCKLOW, Spike - The Alchemy of Paint: Art, Science, and Secrets from the Middle Ages. London: Marion Boyars, 2009. [ Links ]

BUQUET, Thierry - “Animali Extranea et Stupenda ad Videndum: Describing and Naming Exotics Beasts in Cairo Sultan’s Menagerie”. In GARCÍA, Francisco de Asís García; VADILLO, Mónica Ann Walker; PICAZA, María Victoria Chico (Eds.) - Animals and Otherness in the Middle Ages: Perspectives across disciplines. BAR International Series 2500. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2013, pp. 25-34. [ Links ]

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY - “Griffin’s Claw of St. Cuthbert”. [Online]. [Accessed 14 February 2018]. Available at http://www.learn.columbia.edu/treasuresofheaven/relics/Griffins-Claw-of-St-Cuthbert.php. [ Links ]

DASTON, Lorraine J.; PARK, Katharine - Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750. New York: Zone Books, 2001. [ Links ]

DUFFIN, Christopher J. - “Fish, Fossil, and Fake: Medicinal Unicorn Horn”. in DUFFIN, Christopher J.; GARDNER-THORPE, C.; MOODY, R.T.J. (Eds.) - Geology and Medicine: Historical Connections. Geological Society of London Special Publications 452. London: The Geological Society of London, 2017, pp. 211-259. [ Links ]

EAMON, W. - Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994. [ Links ]

ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA - “Aurochs”. [Online]. [Accessed 4 April 2018]. Available at https://www.britannica.com/animal/aurochs. [ Links ]

ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA - “Bison”. [Online]. [Accessed 4 April 2018]. Available at https://www.britannica.com/animal/bison. [ Links ]

ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA - “Ox”. [Online]. [Accessed 4 April 2018]. Available at https://www.britannica.com/animal/ox-mammal-Bos-taurus. [ Links ]

FRICKE, Beate - “Matter and Meaning of Mother-of-Pearl: The Origins of Allegory in the Spheres of Things”. GESTA 51/1 (2012), pp. 35-53. [ Links ]

FRIEDMAN, John Block; FIGG, Kristen Mossler (Eds.) - Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middles Ages: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland, 2000. [ Links ]

GONTERO-LAUZE, Valérie - Les Pierres du Moyen Age: Anthologie des lapidaires médiévaux. Paris: Société d’édition Les Belles Lettres, 2016. [ Links ]

GOTFREDSEN, Lise - The Unicorn. Translated by Anne Born. New York: Abbeville Press, 1999. [ Links ]

GREEN, Nile - “Ostrich Eggs and Peacock Feathers: Sacred Objects as Cultural Exchange between Christianity and Islam”. Al-Masāq 18/1 (2006), pp. 27-78. DOI: 10.1080/09503110500222328. [ Links ]

GUÉRIN, Sarah M - “Forgotten Routes? Italy, Ifrīqiya and the TransSaharan Ivory Trade”. Al-Masaq 25/1 (2013), pp. 70-91. DOI: 10.1080/09503110.2013.767012. [ Links ]

HAHN, Cynthia - Strange Beauty: Issues in the Making and Meaning of Reliquaries, 400-circa 1204. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012. [ Links ]

HASSIG, Debra - Medieval Bestiaries: Text, Image, Ideology. RES Monographs on Anthropology and Aesthetics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. [ Links ]

KENSETH, Joy (Ed.) - The Age of the Marvelous. Hanover: Hood Museum of Art/Darmouth College, 1991. [ Links ]

KESSLER, Herbert L. - “The Eloquence of Silver: More on the Allegorization of Matter”. in HECK, Christian (Ed.) - L'alegorie dans l'art du Moyen Age: formes et fonctions; heritages, creations, mutations. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011, pp. 49-64. [ Links ]

KINOSHITA, Sharon - “Animals and the Medieval Culture of Empire”. in COHEN, Jeffrey Jerome (Ed.) - Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: Ethics and Objects. Washington DC: Oliphaunt Books, 2012, pp. 35-64. [ Links ]

KLINGENDER, Francis D. - Animals in Art and Thought to the End of the Middle Ages. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1971. [ Links ]

LAVERS, Chris - The Natural History of Unicorns. London: Granta Books, 2009. [ Links ]

LEVENSON, Jay A. (Ed.) - Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. Washington, New Haven, and London: National Gallery of Art and Yale University Press, 1991. [ Links ]

LUGLI, Adalgisa - Naturalia et Mirabilia: Les cabinets de curiosités en Europe. Translated by Marie-Louise Lentengre. Paris: Adam Biro, 1998. [ Links ]

MARRACHE-GOURAUD, Myriam - “Les Secrets de la Licorne”. in MONCOND’HUY, Dominique (Ed.) - La Licorne et le Bézoard. Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2013, pp. 396-397. [ Links ]

MAXWELL-STUART, P.G. - The Occult in Medieval Europe, 500-1500: A Documentary History. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. [ Links ]

MONCOND’HUY, Dominique (Ed.) - La Licorne et le Bézoard. Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2013. [ Links ]

MUSÉE DU LOUVRE - Le trésor de Saint-Denis. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1991. [ Links ]

PLUSKOWSKI, Aleksander - “Narwhals or Unicorns? Exotic Animals as Material Culture in Medieval Europe”. European Journal of Archaeology 7.3 (2004), pp. 291-313. [ Links ]

POMIAN, Krzysztof - “La Wunderkammer entre trésor et collection particuliere”. in MONCOND’HUY, Dominique (Ed.) - La Licorne et le Bézoard. Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2013, pp. 17-27. [ Links ]

RECHT, Roland - “Introduction”. in LUGLI, Adalgisa - Naturalia et Mirabilia: Les cabinets de curiosités en Europe. Translated by Marie-Louise Lentengre. Paris: Adam Biro, 1998, pp. 23-29. [ Links ]

ROBERTSON, Kellie - “Exemplary Rocks”. in COHEN, Jeffrey Jerome (Ed.) - Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: Ethics and Objects. Washington DC: Oliphaunt Books, 2012, pp. 91-122. [ Links ]

ROSS, Leslie - Artists of the Middle Ages. Westport and London: Greenwood Press, 2003. [ Links ]

RUDWICK, Martin J.S. - The Meaning of Fossils: Episodes in the History of Paleontology. Second Edition. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1985. [ Links ]

SCHRADER, J. L - “A Medieval Bestiary”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 44/1 (Summer 1986), pp. 1-56. [ Links ]

SHEPARD, Odell - The Lore of the Unicorn. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1967. [ Links ]

STRATFORD, Jenny - Richard II and the English Royal Treasure. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2012. [ Links ]

WEINRYB, Ittai - “Beyond Representation: Things - Human and Nonhuman”. in MILLER, Peter N. (Ed.) - Cultural Histories of the Material World. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013, pp. 172-186. [ Links ]

WEINRYB, Ittai - “Living Matter: Materiality, Maker, and Ornament in the Middle Ages”. Gesta 52 (Fall 2013), pp. 113-132. [ Links ]

ZINK, Michael - “Nature in the Medieval World”. in MYERS, Nicole R. (Ed.) - Art and Nature in the Middle Ages. New Haven and London: Dallas Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2016, pp. 15-26. [ Links ]

Como citar este artigo | How to quote this article:

STEIN, Chantal - “Medieval Naturalia: Identification, Iconography, and Iconology of Natural Objects in the Late Middle Ages”. Medievalista 29 (Janeiro - Junho 2021), pp. 211-241. Disponível em https://medievalista.iem.fcsh.unl.pt.

Data recepção do artigo / Received for publication: 26 de Novembro de 2019

Data aceitação do artigo / Accepted in revised form: 5 de Junho de 2020

[1] FRIEDMAN, John Block; FIGG, Kristen Mossler (Eds.) - Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middles Ages: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland, 2000; KENSETH, Joy, (Ed.) - The Age of the Marvelous. Hanover: Hood Museum of Art/Darmouth College, 1991; LEVENSON, Jay A. (Ed.) - Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. Washington, New Haven, and London: National Gallery of Art and Yale University Press, 1991; PLUSKOWSKI, Aleksander - “Narwhals or Unicorns? Exotic Animals as Material Culture in Medieval Europe”. European Journal of Archaeology 7/3 (2004), pp. 291-313; DASTON, Lorraine J.; PARK, Katharine - Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750. New York: Zone Books, 2001.

[2] See DASTON, Lorraine J.; PARK, Katharine - Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750…; KENSETH, Joy - Age of the Marvelous…; LUGLI, Adalgisa - Naturalia et Mirabilia: Les cabinets de curiosités en Europe. Translated by Marie-Louise Lentengre. Paris: Adam Biro, 1998; MONCOND’HUY, Dominique (Ed.) - La Licorne et le Bézoard. Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2013.

[3] The iconology of materials refers to the study of materials and their metaphoric significance. It assumes that physical matter has certain symbolic values, established by texts, which can be independent from and even unrelated to the object itself. There is a growing field of research focusing on this mode of analysis. See WEINRYB, Ittai - “Living Matter: Materiality, Maker, and Ornament in the Middle Ages”. Gesta 52 (Fall 2013), pp. 113-114.

[4] Quoted in DASTON, Lorraine J.; PARK, Katharine - Wonders and the Order of Nature…, pp. 44. See also pp. 14-23; and KLINGENDER, Francis D. - Animals in Art and Thought to the End of the Middle Ages. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1971, p. 339.

[5] Animals were used to illustrate truths about human behavior, providing a means of gaining perspective on the human condition and the individual’s place within the universe. See BENTON, Janetta Rebold - The Medieval Menagerie: Animals in the Art of the Middle Ages. New York: Abbeville Press, 1992; and SCHRADER, J. L - “A Medieval Bestiary”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 44/1 (Summer 1986), p. 5.

[6] BENTON, Janetta Rebold - The Medieval Menagerie…, p. 66.

[7] See FRIEDMAN, John Block; FIGG, Kristen Mossler - Trade, Travel, and Exploration…, p. 172; and LUGLI, Adalgisa - Naturalia et Mirabilia…, p. 51.

[8] Today we call animals “exotic” but that adjective was rarely used in medieval times and never applied to animals before the sixteenth century. In medieval Latin texts, foreign animals are called extranea (foreign), peregrinus (alien, roving), ultramarinae (overseas), mirabilia (marvelous, wonderful), and stupenda (astonishing, amazing, surprising). See BUQUET, Thierry. “Animali Extranea et Stupenda ad Videndum: Describing and Naming Exotics Beasts in Cairo Sultan’s Menagerie”. in GARCÍA, Francisco de Asís García; VADILLO, Mónica Ann Walker; PICAZA, María Victoria Chico (Eds.) - Animals and Otherness in the Middle Ages: Perspectives across disciplines. BAR International Series 2500. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2013, p. 27.

[9] PLUSKOWSKI, Aleksander - “Narwhals or Unicorns?”…, p. 298. See also FRIEDMAN, John Block; FIGG, Kristen Mossler - Trade, Travel, and Exploration…, p. 181 and pp. 629-631.

[10] MARRACHE-GOURAUD, Myriam - “Les Secrets de la Licorne”. in MONCOND’HUY, Dominique (Ed.) - La Licorne et le Bézoard. Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2013, pp. 396-397; PLUSKOWSKI, Aleksander - “Narwhals or Unicorns?”…

[11] SHEPARD, Odell - The Lore of the Unicorn. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1967, pp. 254-270. See also DUFFIN, Christopher J. - “Fish, Fossil, and Fake: Medicinal Unicorn Horn”. in DUFFIN, Christopher J.; GARDNER-THORPE, C.; MOODY, R.T.J. (Eds.) - Geology and Medicine: Historical Connections. Geological Society of London Special Publications 452. London: The Geological Society of London, 2017, p. 215.

[12] LEVENSON, Jay. A. (Ed.) - Circa 1492…, pp. 126-127; SHEPARD, Odell - Lore of the Unicorn…, pp. 130-131.

[13] ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA - “Aurochs”. [Online]. [Accessed 4 April 2018]. Available at https://www.britannica.com/animal/aurochs; ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA - “Ox”. [Online]. [Accessed 4 April 2018]. Available at https://www.britannica.com/animal/ox-mammal-Bos-taurus; ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA - “Bison”. [Online]. [Accessed 4 April 2018]. Available at https://www.britannica.com/animal/bison.

[14] STRATFORD, Jenny - Richard II and the English Royal Treasure. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2012, p. 314; FRIEDMAN, John Block; FIGG, Kristen Mossler - Trade, Travel, and Exploration…, pp. 63-66; LUGLI, Adalgisa - Naturalia et Mirabilia…, pp. 46-48.

[15] Guérin argues that ivory was traded into Europe via trans-Saharan caravan routes. Conceivably, other goods such as ostriches could have been traded along such routes as well. See GUÉRIN, Sarah M. - “Forgotten Routes? Italy, Ifrīqiya and the TransSaharan Ivory Trade”. Al-Masaq 25/1 (2013), pp. 70-91; and GREEN, Nile - “Ostrich Eggs and Peacock Feathers: Sacred Objects as Cultural Exchange between Christianity and Islam”. Al-Masāq 18/1 (2006), pp. 27-78.

[16] MAGNUS, Albertus - On Animals: A Medieval Summa Zoologica. Translated and annotated by Kenneth F. Kitchell Jr. and Irven Michael Resnick. Volume 1. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999, pp. 45-53.

[17] ROSS, Leslie - Artists of the Middle Ages. Westport and London: Greenwood Press, 2003, p. 18.

[18] Boehm and Holcomb find this metaphor problematic, and Shepard suggests Christians may have forced it onto the original tale. See BOEHM, Barbara Drake; HOLCOMB, Melanie - “Animals in Medieval Art”…; and SHEPARD, Odell - Lore of the Unicorn…, pp. 49-51.

[19] SHEPARD, Odell - Lore of the Unicorn…, p. 48.

[20] Aelian was actually describing his monoceros, which was often later confused with and thought to be the unicorn. It is important to note that, according to Shepard, the word for “rings” can also be translated as “spirals”. See SHEPARD, Odell - Lore of the Unicorn…, pp. 36, 103, and 265.

[21] Arctic whales very rarely appear in bestiaries, though they are mentioned in Albertus Magnus’ De animalibus and the Old Norse Speculum Regale. Neither text mentions a spiraling tusk; the spiral twist seems to have only been associated with unicorns. See GOTFREDSEN, Lise - The Unicorn. Translated by Anne Born. New York: Abbeville Press, 1999, p. 152; LAVERS, Chris - The Natural History of Unicorns. London: Granta Books, 2009, pp. 96-97; and PLUSKOWSKI, Aleksander - “Narwhals or Unicorns?”…, pp. 304-308.

[22] See PLUSKOWSKI, Aleksander - “Narwhals or Unicorns?”…, p. 306; and GOTFREDSEN, Lise - The Unicorn…, p. 154.

[23] BUCKLOW, Spike - The Alchemy of Paint: Art, Science, and Secrets from the Middle Ages. London: Marion Boyars, 2009, pp. 254, 266.

[24] LEVENSON, Jay A. (Ed.) - Circa 1492…, pp. 126-127. See also SHEPARD, Odell - Lore of the Unicorn…, pp. 130-131.

[25] The green color visible around the pinholes indicates copper corrosion and suggests the metal strips were originally copper. They likely would have been gilded. See PLUSKOWSKI, Aleksander - “Narwhals or Unicorns?”…, p. 302; and LEVENSON, Jay A. (Ed.) - Circa 1492…, p. 126.

[26] See Jean-Claude Bonne -“De l’ornement dans l’art médiéval: VIIe-XIIe siècle; le modèle insulaire”. in BASCHET, Jérôme ; SCHMITT, Jean-Claude (Éds.) - L’image: fonctions et usages des images dans l’Occident médiéval; actes du 6e International Workshop on Medieval Societies, Centro Ettore Majorana (Erice, Sicile, 17-23 octobre 1992). Paris: Léopard d’Or, 1996, pp. 207-249; and BONNE, Jean-Claude - “Entre l’image et la matière: la choséité du sacré en Occident”. in SANSTERRE, Jean-Marie; SCHMITT, Jean-Claude (Eds.) - Les images dans les sociétés médiévales : pour une histoire comparée. Bulletin de l’Institut Historique belge de Rome 69 (1999), pp. 77-111.

[27] See RECHT, Roland - “Introduction”. in LUGLI, Adalgisa - Naturalia et Mirabilia: Les cabinets de curiosités en Europe. Translated by Marie-Louise Lentengre. Paris: Adam Biro, 1998, p. 25.

[28] ZINK, Michael - “Nature in the Medieval World”. in MYERS, Nicole R. (Ed.) - Art and Nature in the Middle Ages. New Haven and London: Dallas Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2016, p. 18. See also WEINRYB, Ittai - “Living Matter”…

[29] HAHN, Cynthia - Strange Beauty: Issues in the Making and Meaning of Reliquaries, 400-circa 1204. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012, pp. 8-26.

[30] AINSWORTH, Thomas - "Form vs. Matter". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [Online]. Spring 2016 ed. ZALTA, Edward N. (Ed.) [Accessed 7 February 2018]. Available at https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/form-matter/.

[31] Scholars like to believe that material signification existed throughout the Middle Ages and was applied to all types of materials, and that selection of materials was based on their significance. How true this actually was is less clear. See WEINRYB, Ittai - “Living Matter”…

[32] MAXWELL-STUART, P.G. - The Occult in Medieval Europe, 500-1500: A Documentary History. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005, pp. 2-4; ROBERTSON, Kellie - “Exemplary Rocks”. in COHEN, Jeffrey Jerome (Ed.) - Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: Ethics and Objects. Washington DC: Oliphaunt Books, 2012, pp. 98-100.

[33] MUSÉE DU LOUVRE - Le trésor de Saint-Denis. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1991, pp. 310-311.

[34] COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY - “Griffin’s Claw of St. Cuthbert”. [Online]. [Accessed 14 February 2018]. Available at http://www.learn.columbia.edu/treasuresofheaven/relics/Griffins-Claw-of-St-Cuthbert.php; BRITISH MUSEUM - “Animal Remains”. [Online]. [Accessed 14 February 2018]. Available at http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=44328&partId=1&people=46119&peoA=46119-1-8&page=1.

[35] BUCKLOW, Spike - Alchemy of Paint…, pp. 248-251. See also PSEUDO-ROGER BACON - Speculum alchemiae, translated in MAXWELL-STUART, P.G. - Occult in Medieval Europe…, p. 197.

[36] KESSLER, Herbert L. - “The Eloquence of Silver: More on the Allegorization of Matter". in HECK, Christian (Ed.) - L'alegorie dans l'art du Moyen Age: formes et fonctions; heritages, creations, mutations. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011, pp. 54-55. See also PSEUDO-ROGER BACON - Speculum alchemiae, translated in MAXWELL-STUART, P.G. - Occult in Medieval Europe…, p. 197.

[37] KESSLER, Herbert L. - “Eloquence of Silver”…, pp. 50-56.

[38] KESSLER, Herbert L. - “Eloquence of Silver”…, p. 52.

[39] POMIAN, Krzysztof - "La Wunderkammer entre trésor et collection particuliere”. in MONCOND’HUY, Dominique (Ed.) - La Licorne et le Bézoard. Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2013, pp. 17-27.

[40] KINOSHITA, Sharon - “Animals and the Medieval Culture of Empire”. in COHEN, Jeffrey Jerome (Ed.) - Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: Ethics and Objects. Washington DC: Oliphaunt Books, 2012, pp. 35-64.

[41] LUGLI, Adalgisa - Naturalia et Mirabilia…, pp. 54-67.

[42] DASTON, Lorraine; PARK, Katharine - Wonders…, pp. 68-103; LUGLI, Adalgisa - Naturalia et Mirabilia…, pp. 39-40.

[43] EAMON, W. - Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994, pp. 223-224; DASTON, Lorraine; PARK, Katharine - Wonders…, p. 68.

[44] GREEN, Nile - “Ostrich Eggs”…, p. 35; DASTON, Lorraine; PARK, Katharine - Wonders…, pp. 67-88.

[45] THEOPHILUS - On Divers Arts. Translated by John Hawthorne and Cyril Stanley Smith. New York: Dover Publications, 1979, p. 78.

[46] HAHN, Cynthia - Strange Beauty…, p. 28.

[47] Suger, translated in ROSS, Leslie - Artists of the Middle Ages…, p. 89.

[48] See HAHN, Cynthia - Strange Beauty…, pp. 8-26. Though Hahn is discussing reliquaries, the same concepts can be applied to mounts for naturalia.

[49] HASSIG, Debra - Medieval Bestiaries: Text, Image, Ideology. RES Monographs on Anthropology and Aesthetics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 172.

[50] ROBERTSON, Kellie - “Exemplary Rocks”… See also FRIEDMAN, John Block; FIGG, Kristen Mossler - Trade, Travel, and Exploration…, pp. 208-209; and WEINRYB, Ittai - "Beyond Representation: Things - Human and Nonhuman". in MILLER, Peter N. (Ed.) - Cultural Histories of the Material World. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013, p. 175.

[51] GONTERO-LAUZE, Valérie - Les Pierres du Moyen Age: Anthologie des lapidaires médiévaux. Paris: Société d’édition Les Belles Lettres, 2016, pp. 50-54.

[52] See discussion in FRICKE, Beate - “Matter and Meaning of Mother-of-Pearl: The Origins of Allegory in the Spheres of Things”. GESTA 51/1 (2012), p. 45.

[53] FFRICKE, Beate - “Matter and Meaning”…

[54] LUGLI, Adalgisa - Naturalia et Mirabilia…, p. 43.

[55] This story derives from a Greek version of the Physiologus. It is not represented in earlier bestiaries and is very seldom brought together with the virgin-capture story. It doesn’t appear in Western literature or art until the fifteenth century, after the belief in the alexipharmic qualities of the alicorn were already well established. See DUFFIN, Christopher J. - “Fish, Fossil, and Fake”…, p. 214; and SHEPARD, Odell - Lore of the Unicorn…, pp. 60-61.

[56] BENTON, Janetta Rebold - Medieval Menagerie…, p. 77.

[57] The Danny Jewel is Elizabethan and therefore outside the scope of the medieval iconology of materials so its adornment will not be analyzed here. However, its existence and overall shape can be used as a reference for what earlier, non-extant pieces may have looked like.

[58] In later centuries, alicorn was also considered effective against “poisonous diseases” and sold as medicine in various forms, powdered and otherwise. See DUFFIN, Christopher J. - “Fish, Fossil, and Fake”…; and SHEPARD, Odell - Lore of the Unicorn…

[59] LEVENSON, Jay. A (Ed.) - Circa 1492…, pp. 129-131; RUDWICK, Martin J.S. - The Meaning of Fossils: Episodes in the History of Paleontology. Second Edition. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1985, pp. 30-32.

[60] The two other extant tongue-stands are in the Schatz des Deutschen Ordens in Vienna and the Grünes Gewölbe in Dresden. See LEVENSON, Jay A. (Ed.) - Circa 1492…, pp. 129-131.

[61] Pseudo-al Majriti, Ghayat al-hakim [Picatrix], translated in MAXWELL-STUART, P.G. - Occult in Medieval Europe…, pp. 171-172.

[62] See SHEPARD, Odell - Lore of the Unicorn…, pp. 147-149.

[63] See LEVENSON, Jay A. (Ed.) - Circa 1492…, p. 19; LUGLI, Adalgisa - Naturalia et Mirabilia; POMIAN, Krzysztof - “La Wunderkammer”…, pp. 21-23; and RECHT, Roland - “Introduction”…, pp. 23-24.