Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.10 no.Especial Lisboa jun. 2016

Digital resources in popular media practices in Brazil: strategies to reduce asymmetries in the public debate

Ana Cristina Suzina *

* PhD student in Political and Social Sciences at CriDIS (Centre de recherches interdisciplinaires Démocratie Institutions Subjectivités), Université Catholique de Louvain, Place de l'Université 1, 1348, Louvain la Neuve, Belgium, (anasuzina@hotmail.com).

ABSTRACT

This article discusses issues related to the development of popular media in the context of an asymmetric democracy, such as Brazil. It is mostly based in an empirical study which included 55 media experiences all over the country. The objective is to observe the use of digital resources in media practices developed by social movements and community associations, analyzing how it can contribute to the emergence of a plurality of voices in the public debate. The findings suggest a concrete improvement in the media production process and also in the capacity of reaching audiences, especially those outside their niches. But as long as this enlargement of diffusion range can be read as a progress, it also reveals paradoxes while grassroots communities stand far from a stable connected world. The answer could come from a stronger articulation between digital and analogical media strategies.

Keywords: community media, alternative media, digital culture, Internet, Brazil, asymmetries.

Introduction: Asymmetries as a challenge for democracy

Manuel Castells defends the idea of communication as a central power in modern societies and argues that the emergence of digital culture has made it greater than ever (CASTELLS, 2013). This article takes into consideration the use of digital resources in popular media1 practices in Brazil to propose a discussion about these assumptions in a context of what we call as asymmetries. The aim is to debate how popular media actors use online and offline resources in order to improve their presence and legitimacy in the public debate.

Brazil is a country recognized by economic, political and social inequalities, that already consist a great barrier to the development of popular media. The inequality in the media sphere in the country seems to be very close to the social and economic inequalities. Vilson Vieira Jr. establishes a relationship between poverty in different Brazilian regions and concentration of media. He takes as reference a study of the Instituto de Estudos e Pesquisas em Comunicação (EPCOM), in 2006, that pointed out that “the poorer is the region the highest is the level of media concentration, i.e., the lower is the number of actors owning media such as radio and television”. (Vieira Jr., 2007)

The problem that I am trying to address is that an unequal distribution of channels of communication, on the top of multiple lacks of resources, in association with social dynamics that make some voices more legitimate than others (Honneth, 1995) (Bourdieu, 1979), funds an asymmetric relationship between the actors. First, there is this straight reciprocity between issues of redistribution and recognition (FRASER, 2003), being both determinant factors of embrittlement. The lack of resources – such as licenses, infrastructure, equipment, people, financial sources etc. – produces both difficulties for communicating as well as for getting the information recognized as valuable. Secondly, as a consequence, these challenges touch the democratic ideals of equality among citizens, and of opportunities of participation and contestation (Dahl, 2005; Dahl R. , 2001).

For Fraser, the parity of participation depends on something more than redistribution and recognition. She talks about representation as a category to discuss political asymmetries and as a condition for reaching social justice (Fraser, Reframing justice in a globalizing world, 2010). In this debate, the author calls attention to the process of framing. According to her, the “who” and the “what” of social justice are defined through a frame and “how” this frame is designed is the very question for challenging the structures that produce injustice. Luis Felipe Miguel argues that representation and legitimacy should not be taken for granted in any democracy (Miguel, Autorização e accountability na representação democrática, 2012). For him, the legitimate presence of different discourses in the public debate should not put aside questions such as how long these discourses are representative, who they represent, and what is the availability of resources for each actor to take part in the struggle for discursive representativeness.

In this sense, this article positions media as a central intermediary in the political sphere (François & Neveu, 1999), as they produce the visibility required for turning things public – public in the sense of concretely visible but also of common, of shared (Barbero, 2001). In the Brazilian case, inequalities in the media sphere are identified as one of the faces of an asymmetric democracy, considering the difficulties of a large number of actors for communicating and intervening in the public debate. Social movements and community associations play, then, a central role by pushing these limits and challenging the process of frame designing.

It is supposed that the digital culture can introduce changes in contexts of asymmetries, considering that “the entry barriers in the Internet industry are much lower than in the traditional communication industry” (Castells, 2013, p. xx). The development of Internet, for instance, shakes the conception and the practice of democracy exactly because it touches the balance of power between representatives and represented (Cardon, 2010). In the particular case analyzed in this article, it seems to be actually contributing to the improvement of popular media practices in Brazil, but it is equally important to consider its limits for building up the ideal scenario of democratic participation.

The problem of getting visibility in a context of asymmetries

This reflection starts with the assumption that Brazil can be considered as a stratified society. According to Fraser’s definition, stratified societies are those “whose basic institutional framework generates unequal social groups in structural relations of domination and subordination” (Fraser, 1992, p. 122). Even if there is general recognition of improving social conditions in Brazil in the last decades, the country is still far from a situation of equality2, something that reflects in the media framework, as already mentioned.

Taking particularly the aspect of parity of participation highlighted by Fraser (1992; Fraser, 2010), issues of representativeness and legitimacy can be easily observed in the discussion about who is allowed to speak in the public debate. It is where asymmetric relationships can be observed.

Several scholars and social organizations have approached the lack of visibility of social issues and the lack of plurality of voices in Brazilian mainstream media (Miguel, Biroli, & Duailibe, 2013) (Santos L. J., Jan-Jul/2009) (Piscitelli, 1996). For one example, the Agência Nacional dos Direitos da Infância (ANDI) has conducted an analysis of 40 regional and national newspapers from 2007 to 2012, looking for articles approaching actions developed by civil society organizations. The result revealed that those dealing with basic public issues had almost none coverage: from more than 2,3 thousand articles analyzed, actions regarding people living in the streets were the topic of 0,4% of the articles, those dealing with racial discrimination were the topic of 0,9% of them, mobilizations around quilombolas, indigenous and other traditional communities were the topic of 2,9% of the sample, and actions focusing on human rights were the topic of 5% of the articles (ANDI, 2014). These invisibilities (Sousa Santos, 2007) consist of one of the faces of the asymmetries, considering the concept of journalism as a gate keeper (White, 1950), and is one of the reasons for the development of popular media initiatives.

In this article, however, I propose to observe another face, the one that refers to dynamics related exactly to those initiatives created by social movements and community associations. Particularly, my field researches revealed in one hand struggles for getting out of stereotypes that could weaken the legitimacy of some groups of having their own voice and their recognition as equals in the media sphere. In the other hand, they suggested a strategy of convenience concerning the recognition of the power of popular media. Their importance is recognized when the use of their networks can bring benefits to someone and, in the opposite, when it comes to apply any kind of censorship to limit their influence over the society.

In the Brazilian media sphere, even if there is a valorization coming from the research since the 1970’s, popular media can still be depicted as something fragile, done by non-professionals and without appropriate resources. “Is it journalism?”, for instance, was one of the central questions about Mídia Ninja during Roda Viva, one of the main debate programs in the Brazilian television, just after the protests of June 2013 (TV Cultura, 2013). It focused on Mídia Ninja3, but it actually concerned all kinds of media initiatives that got attention and audience during the mobilizations by broadcasting alternative views and narratives about what was happening in the streets.

Such an evaluation shows the logic of the expert language (Bourdieu, 1979) that lies upon gaps established on distinctions between what is valuable and what is not. It limits the possibility of taking this kind of initiative as equal in the media sphere and, consequently, avoids considering the voices behind it as legitimate. Accordingly, some actors also reveal a constructed common sense about what these media are expected to seem and to transmit, as reported by Aécio Diniz, a program coordinator in Rádio Casa Grande FM4, an educative radio station in Nova Olinda (CE), Northeast region:

“Once, Alemberg5 was with visitants here and someone asked him, while he was talking about the radio, and he said that we have programs broadcasting jazz, blues, classical music. Then the person looked to him and asked: ‘Here, in Nova Olinda, how come? Do you have a jazz program? Instrumental music?’ And he said ‘Yes, we do have a program about jazz in Nova Olinda’. And the person insisted: ‘But in a small city like this, how come people will listen to jazz, to instrumental music?’ And he answered that we have it here. ‘And what is the audience share, the number of people who listen to this radio?’ And he answered 100%. And the person was astonished. ‘But how come 100%?’ ‘Yes, 100% more than in your city where there is not any jazz program’, Alemberg said (Diniz & Marope, 2013).

This statement suggests a perspective where society looks to popular media – and their audience – as something inferior. As they would be non-professional, the information transmitted by them could not be trusted. In the case of Mídia Ninja, the fact that they were not following patterns of journalism would make them illegitimate sources. But at the same time, they would not be expected to be professional, because they are marginal and should keep the stereotypes generally directed towards their audience. Reading the example of Casa Grande radio, they should not broadcast what is considered to be genres only consumed by people living in certain conditions different from a poor village in the countryside of the Brazilian arid region. Casa Grande might be one individual case, but the reference – and complain – towards stereotypes carried over different social groups was recurrent during the field research (Fuser & Ferreira, Limites e Perspectivas da Comunicação Cidadã em Chiador, MG, 2013) (Marinho Jr., 2013) (Ramalho, 2014) (Rodrigues & Gois, 2014) (Santos I. F., 2013) (Santos & Sena, 2013) (Santos J. , 2014). This perspective hurts both the perspective of legitimacy and representation of these media and their members.

On the other way around, these media are also very searched by political actors under purposes of enlarging the number of supporters, especially in the countryside. For instance, during the field visit to Ibiapina radio station, in Florânia (RN)6, Northeast region, a state governor candidate passed by without previous scheduling and wanted to speak on the radio. Evani Tercio, director of the radio station, accepted to take their participation in a program, and explained that, as a community radio, they open the microphone to any authority who wants to address a word to the population.

The candidate and a state deputy took the microphone for around 40 minutes and made strong critics to the government in office at that moment. A member of her team told that they were traveling all around the state and would stop in every community radio that they crossed by on their way. For them, these media have the power in the countryside. It is a very contradictory statement, considering all the difficulties that these media confront in the search for resources (see below). But, according to Orlando Berti, around 15% of the legalized community radios in Brazil are inactive, lacking of operational conditions, and only function during electoral periods to serve political interests (Berti, 2016).

Probably for the same recognition as a local power, the Ibiapina radio station works under the pressure of local administration. Jota Junior, a volunteer broadcaster who has a daily program in the morning, and Tercio told that there was a news broadcast in the schedule. Besides reading articles from the regional press, they used to diffuse information about the city and got a great audience. The approach to local issues was disapproved by the local mayor, who called the priest and promised to cut the financial support given both to the radio and to the Catholic Church – the Ibiapina radio station is owned by a local association, but was created with the support of the local parish and still counts on it to survive. The news’ diffusion was vanished from the whole schedule. Programs done by local associations suffer the same pressure. The chamber of representatives went to Justice against an association working on handicap because of complains diffused in their broadcast. (Jr & Tercio, 2013) The result is that, even if Ibiapina radio is the only medium of the city, it is not free for discussing political and social issues, which is one of the objectives of any community radio.

In the city of Chiador (MG), Southeast Region, the local administration also makes hard the development of the community newspaper Jornal de Chiador. The publication was a result of an academic work. Rodrigo Galdino studied Journalism and decided to create the first medium in his own city of around 2,8 thousand inhabitants. The financial support comes from a scholarship for a research project related to community media attached to the Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, but Galdino counted on local structures to run the process with the participation of local dwellers. As long as the newspaper discusses social issues of the city, it was taken as a publication of opposition and the local administration decided to forbidden the team of meeting in school rooms or other public places. (Fuser, 2013)

The dynamics affecting popular media, like those just described, illustrate the debate proposed around the idea of an asymmetric democracy. The unequal access to structures goes in pair with the lack of – or fragile – recognition of the legitimacy of these voices. These social actors are, therefore, included in the public debate but the parity of participation is not granted. In such a context, pretending that all interlocutors are equals, under the assumption of freedom of expression, masks structural deficiencies and political pressures that need to be solved if there is a clear intention of promoting a qualified public debate.

The sample and the methodology

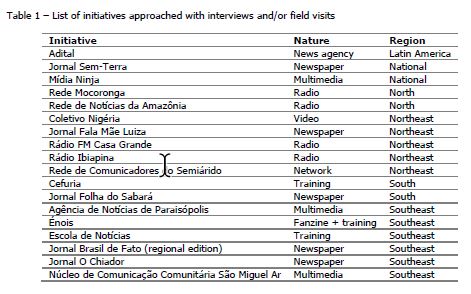

This analysis is based in two field researches conducted in October-December of 2013 and April-May of 2014 in the domain of popular media in Brazil. The studies enrolled two samples7. The first one was composed by 18 initiatives distributed all over the country, with ranges of diffusion varying from local to national audiences (Table 1). This group was approached with field visits for observation of practices and/or interviews with media actors, mainly the leading actors of each experience.

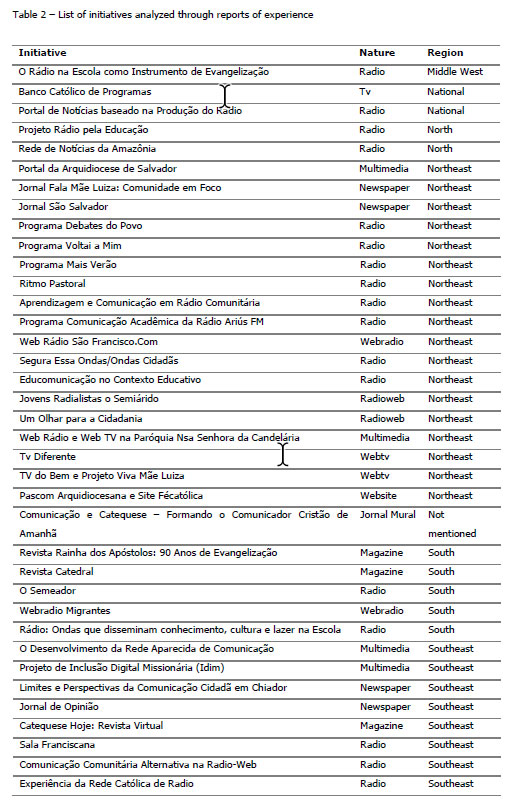

The second sample was composed by 37 reports written by popular media actors and presented on a national event promoted by the Catholic Church to support and motivate the debate around communication (Table 2). It is important to highlight that, despite the religious affiliation of the event, only half of this sample was composed by experiences directly related to the Catholic Church and they were still considered as relevant taking into account the historical support offered by some sectors of this church to social and popular movements, and particularly to the development of popular communication in the country (Dornelles, 2007).

The analysis of 37 reports was carried out with the support of NVivo software - version 10. The analytical model included three main categories that were transformed into coding labels and applied to the texts. These categories were based in the strengths and weakness of popular media, identified by Cicilia Peruzzo in the end of the 1990s (Peruzzo C. M., 1998) and searched for evolutions in this scenario, considering mainly the introduction of digital resources. The software allowed to identify the occurrence of certain characteristics and make associations between them to enrich the interpretation of the actors’ speeches about their practices.

The field visits and interviews followed the guidelines of the comprehensive sociology (Kaufmann, 1996), highlighting the time spent in discussion with actors. In all cases, the leaders of media practices were interviewed and, in some of them, when it was possible, some members of their team were also approached. The objective was to explore their models of doing media, and mainly the reasons for each choice, including the use of digital resources.

The influence of digital culture

During the research, it was possible to identify that the use of digital technologies is strongly affecting popular media practices. It has an impact on the framework of media ownership and on the access to resources. And it seems to equally interfere in the struggles for representation, while enlarging opportunities of visibility. This situation observed among popular media in Brazil follows an international pattern, as reported by UNESCO, recently. Its document “World trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development” states that the “disruption and change” produced by the use of digital technologies were the main global trend concerning the aspects of freedom, plurality and independence of media, as well as the safety of journalists (Unesco, World trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development, 2014).

On the other hand, it was also possible to observe potential limits of this interference. Digital connection does not seem to be an automatic synonym of exchange in the public sphere, suggesting that the recognition of popular voices would be better related to the articulation between all kinds of media outlets available. This section intends to expose the evidence found about potential contributions and limits of digital culture in popular media regarding the aspects above.

Impacts and challenges on structural conditions

The distribution of internet connection and the proportion of average numbers of internet users around the world follows the general patterns of inequalities, meaning the richer is a region, the most connected it is (Peruzzo C. M., 2005). Particularly, in Latin America, the access to digital platforms of communication has been increasing, especially influenced by the use of mobile broadband. This evolution is, however, very dependent on private corporations, which makes improvements more likely to follow the potential of markets than aspects such as social inclusion (Unesco, Tendencias mundiales en libertad de expresión y desarrollo de los medios: Situación regional en América Latina y el Caribe, 2014).

During the field visits, services of internet connection could be find all over the country, but with strong limitations. In Florânia (RN), Northeast region, the local public administration made free connection to internet available in the central square. At night, lots of people gather there to check their social network updates, most of them with mobile phones. It seemed very well, but some people explained that the quality of connection depends on how many people are using the service simultaneously and that, when there is a problem, the only internet provider in the city can take weeks to put it on again. Ibiapina Radio, the community radio station of the city, counts on a paid private contract in order to have a more stable connection.

In Nova Olinda (CE), Northeast region, the general service provided for regular clients offer 300k of bandwidth. Even the mailbox can take half an hour to exhibit new messages; opening one of them can take long. There is also only one provider in the city and the corporate contracts can arrive to two megabytes of bandwidth, which is used by Fundação Casa Grande and its educative radio station. Both initiatives count a lot on the internet for accessing content and improving the variety of production.

In this sense, the observations reveal the dependency on a very fragile – and private –technological structure but still a contribution to the production process, while internet provides an opportunity for accessing more sources of information, including shared contents. The Rede de Notícias da Amazônia8, North region, bases its work in the exchange of productions between local radio stations spread in the Amazon Region. According to its coordinators, the low connection avoided the installation of a system where all members could upload and download productions from a common server or website, but even if this connection is unstable, it is enough to send and receive pieces among them (Pereira Rodrigues, 2013).

There is also evidence that the access to internet may be easing the opportunity of reaching new audiences. For Castells, “the advent of digital communication, and the associated changes in organization and culture, have deeply modified the ways in which power relationships operate” (Castells, 2013, p. xix). This author enhances the potential of internet to increase the autonomy of the communicating process, opening opportunities for individuals to produce self-massive information, meaning that a message issued by only one person or group can reach massive audiences without or at least with less interference from owners and regulators of the communicative infrastructure.

The initiatives observed confirm this potential. Some talk about a “revolution of the filters” (Vilela, 2013) (Gurjão & Rocha, 2013), referring to the possibility of broadcasting a message by oneself, without passing by any gatekeeper, as newsrooms journalists are regularly described in the literature. Some mention the possibility of reaching people far away without needing to make important investments in broadcasting equipment (Gonçalves, 2013) (Lara & Gheller, 2013) (Rosembach & Zottis, 2013). For many, it represents an opportunity for passing along a message that otherwise would be confined into already engaged publics, as it was the case of the alternative media that flourished during the mobilizations of June 2013, like Mídia Ninja and Coletivo Nigéria9. For others, it is the chance of breaking down geographical barriers and connecting to the world, even if still striking against structural limitations.

The Fundação Casa Grande started to use social networks and blogs in 2005. Besides the institutional pages, the coordinators of the project motivate the children to have their own blogs and tell the world their news.

“We motivate each kid to have his/her blog, because it is a way for showing themselves off virtually to the world. How the Casa Grande is doing today, there will be people out there in São Paulo, in Japan, that will know the reality of Fundação Casa Grande.” (Diniz & Marope, 2013).

The Rede Mocoronga is a network maintained by an NGO called Saúde e Alegria which gathers popular media practitioners of more than 30 communities in the Amazon Forest. It develops some blogs and other virtual products from the activities realized in the communities, but many of them do not have internet connection – it must be said that in this region some of the communities still have problems for having electric power. It means that all this production is available mainly for people out of the communities themselves. And even in a huge city as São Paulo, where internet connection should not be a problem, media actors talk about the price of connectivity through private services and also about the limits of digital literacy (Ramalho, 2014).

The situation leads to a question regarding the notion of territory. Just like the coordinators of Rádio Casa Grande stated above, in the reports of experience from popular media, there were several descriptions of an “international audience”. There is a kind of de-localization or double-localization in place. While people in the local territory keep using mainly the traditional forms of access to popular media products, digital resources may be reaching audiences out of the communities and sometimes new audiences, such as young people with their smart phones. The evidence suggests that, despite of its instability, digital resources are providing more sources for the media making process as well as allowing access to grassroots productions. An immediate consequence is the increasing variety of contents, even if participatory dynamics are not very clear, as we will see in the following.

Challenges in the field of internal participation

Miguel talks about three dimensions of political representation, the third being the one that concerns the horizontal relationship among those who are represented in the construction of preferences. In this dimension, “the internal dialogue is a crucial moment of the representative process” (Miguel, Autorização e accountability na representação democrática, 2012, p. 11). In the field of popular media, this reflection could be applied to the way these practices include their audiences or communities, in the search of discursive representativeness. Making a reference to the work of Clarissa Rile Hayward, the author argues that an asymmetrical society needs the emergence of new public interests, but they must be built upon the participation of affected people if there is any objective of emancipation (Miguel, Autorização e accountability na representação democrática, 2012, pp. 17-18). All initiatives observed look forward to establishing a dialogue with their communities and audiences, but the ways of doing it vary considerably and could be classified in practices related to indirect and direct participation.

The first trend refers to the concern about the skills of media staff and their straight connection with people concerned by their media. The presence of professionals10 is relatively frequent in popular media environment currently, but training processes are still a permanent objective of the actors, including both technical competencies and the appropriation of realities. For this kind of initiative, knowing the context is so important as knowing how to make an article. The Rede de Notícias da Amazônia, in the Amazon region, take it as one of its main features.

“Another objective that guides the work of the network is the development of the communicators. Several of them are not journalists, they come from other fields of study, some does not have any university degree, but they have a communicative potential, they can collaborate and have a lot to say. So, the Rede de Notícias also works with this objective of training. (...) They also propose experiences inside traditional communities in order to stimulate the encounter with the communities, to make us know. (…) The ideas are not born from nothing, they must come from experiences, we need to see things in order to propose good coverage. This is the proposal of the Rede de Notícias, to meet, to know what happens, to make the Amazon communicators know the Amazon.” (Pereira Rodrigues, 2013)

In this field of training, the impact of digital resources applies in the development of online courses focusing in communities and alternative media actors. For instance, Énois is a media entrepreneurship that begun mobilizing young people to produce a fanzine about their neighborhood in the periphery of São Paulo, Southeast region. The result was so good that the group developed an online platform to teach journalism for youth in the peripheries. In May of 2014, there were 2.600 people from all over the country admitted in an online training program that aimed at “hacking the city”, as described by Nina Weingrill, journalist and one of the leaders of the project. This objective was explained both as a way for better knowing the communities as well as for taking part of the whole city as members of their own neighborhood. The online platform was chosen because of the profile of the participants: “we believe that youth are connected to internet (…) and if there are structural limitations, connection is still what they search for” (Weingrill, 2014).

It is important to observe that this kind of training allows citizens themselves to act as media actors, which is different from preparing communicators to deal with local issues. But in the context of popular media, both strategies have something in common, which is the bottom-up approach, meaning a clear interest on identifying and producing information from the very grassroots, revealing the experiences and challenges lived by the people.

The second aspect relates to the efforts for stimulating or improving direct participation in media productions. All initiatives observed demonstrated willingness to receive contributions from their communities and/or audiences. They are expressed mainly in the report of people asking music in the radios, of comments made by telephone or internet or even when people cross the communicators in the streets, of critics and comments about articles and pieces diffused. Some of the practices even take as a main objective to improve participation, declaring an intention of having more appropriation coming from the community. However, more information is required to analyze the efficacy of the processes concretely put in place to make it possible for people to set a subject in these media.

The communicators engaged in the Núcleo de Comunicação Comunitária São Miguel no Ar11, in the city of São Paulo (SP), Southeast region, take the Fórum dos Moradores as one of their sources for defining topics for coverage (Ramalho, 2014). This Fórum is a local meeting where dwellers come to discuss their needs and complains. The Jornal de Chiador fix posters in the city inviting the inhabitants to take part in the newspaper’s preparatory meetings (Fuser, 2013). All radio coordinators interviewed declared that any community dweller can propose a program, and actually many of these radio stations work with volunteers bringing their interests and passions to the microphone. But there are also rules that must be followed and it is important to know who defines these rules and how they are applied. On the other hand, it may be interesting to understand better how long these initiatives end up by gathering issues still proposed by a minority of the most active individuals in one community.

The reports of popular media actors show a predominance of the use of digital resources to broadcast content, without necessarily involving changes in media management processes. That means, often, to provide more channels to spread contents - for example, the same newspaper can circulate from hand to hand and also have an electronic version, and each story published as a post on a blog or Facebook page. Of the 37 reports analyzed, 25 do not associate the use of digital resources to any participatory process. Among those who mention their use, there is a predominance of social media, especially Facebook. Often, these social networks, as well as e-mail accounts, seem to function as another contact channel between the audience and the media, as a complement or replacement for the telephone. (Suzina, Mais conectados, mais comuns? Recursos digitais nas experiências midiáticas apresentadas no 8º Mutirão Brasileiro de Comunicação, 2015).

As proposed by Miguel, in the context of civil society associations and militant mobilizations, the representativeness depends upon the existence of mechanisms of exchange between leaders and grassroots levels. The recognition of discursive representativeness would be then related to the mechanisms put in place by media actors in order to include more citizens in the definition of the issues. It would determine how long these media are able to produce new public interests based on collective processes. As this study performed a large collection of data from many initiatives, it was not possible neither contemplated to go further in the observation of participatory practices in each medium observed. This information may be taken, then, as exploratory findings that must be better investigated in the future.

Impacts on the political order

The access to digital resources touches directly one of the main barriers for developing popular audiovisual media in Brazil. The regulations around radio and TV projects make it difficult for creating a media as well as for keeping it working, being one of the reasons for the concentration of media ownership.

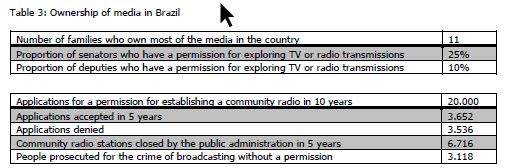

The Intervozes Coletivo Brasil de Comunicação Social is an NGO that defends the right to communication as a way to free people from the hostage of the media controlled by powerful actors. In a film called “Levante sua voz”, they affirm that media content shapes the way people see the world and advocate the democratization of media ownership in order to promote the plurality of views (Ekman, 2009). In this film, they illustrate the control of the media sphere in Brazil by the confrontation of the number of 11 families who own most of the media in the country12 with thousands of applications for getting authorization for the establishment of a community radio station13 (Table 3).

Data collected by Angelo Serpa illustrate the situation with the example of Salvador, in the state of Bahia, Northeast region. According to this researcher, between 1999 and 2005, the national authority has prevented 537 radio stations from starting to work in the city and only 31% of all requests made eventually got a permission (Serpa, 2013). In 2010 and 2011, around two radio stations operating without permission were closed every day all over the country (Paiva, Malerba, & Custódio, 2013, p. 253).

Reports of troubles for getting a permission were abundant during the research, confirming trends identified by Venício A. de Lima and Cristiano Aguiar Lopes, whose research revealed what they called as an “electronic domination”, considering the weight of political influence in the process (Lima & Lopes, O coronelismo eletrônico de novo tipo (1999-2004), 2007). The project for establishing a community radio station in the neighborhood of Brasilândia14, in the northern zone of the city of São Paulo, Southeast Region, started in 1995. Even if the local association begun to broadcast as soon as they got all the equipment required, the legal permission for the Rádio Cantareira FM was given only in 2010. In their report of experience, the coordinators describe a long way of bureaucratic procedures and tension under the pressure of the national authority (Rosembach & Zottis, 2013).

The permission for a community radio station in the neighborhood of Paraisópolis15, also in São Paulo, took 11 years, after an irregular radio station was closed. On top of bureaucracy and efforts for getting all the equipment required, the association of dwellers had to accept that the antenna was placed far away from the studio where the Rádio Nova Paraisópolis operated. Two requests for radio operation in the same region were running at the same time and to avoiding an even larger delay, the community accepted the deal of displacing the antenna, something that solved the immediate problem but costs a lot in terms of quality and maintenance of the operation (Sampaio, 2014).

Community television operations follow the same path. The Fundação Casa Grande maintains its radio station and it also tried to set up a community television channel. After getting all the equipment and training a group for the work, they started to produce some programs about life in the community. It did not last long till the national authority came to put an end in the activity, as reported by one of the current coordinators:

“We put the TV on and then, differently, as the TV was not legal, democratically, it went on. Astonishingly, we got more audience than Globo, because we started to show the people of the city and it was kind of a shock, even for the community, because we arrived with a camera and showed the popular market, we started to show the people, and they turned on their TVs and started to see themselves. Then it reached a huge repercussion in the city. And what happened so? Without all the legality, all this huge bureaucratic process that we must follow, according to the community TV law, we did not have it (the permission), the Anatel came and sealed our transmitter.” (Diniz & Marope, 2013)

Currently, Globo network is the only TV channel producing information in the region, with staff in bigger cities in the state of Ceará. The video production of Fundação Casa Grande is still in place however. They created a kind of video producer house named “Sem Canal”, which means without channel, and develop small pieces about traditions and icons of the region for a national educative channel, TV Futura, that is also owned by Globo.

According to Intervozes, the result of the monopoly of ownership is a homogeneity of issues, sources of information, actors and approaches represented in the public debate. There is a complain regarding the disconnection between the media and the situation of the Brazilian population. The concentration of ownership also means that a lot of the content is produced or selected from urban centers, like São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Brasília (Vieira Jr., 2007), or the capitals of the states, leaving a small space for local facts and perspectives and a lot of room for homogeneity, meaning establishing patterns that do not necessarily correspond to the diversity of Brazilian society.

The example of the community TV of Fundação Casa Grande is already a good one, but plenty of others could be added. For instance, the Rede de Notícias da Amazônia was created to confront this same problem. Tired of seeing themselves through the eyes of media operated from the South and the Southeast, a group of local radio stations decided to gather for producing news under their own perspective and enlarging the audience of this production. After around five years of training and preparatory meetings, the network started to work in 2008 and has currently two shared productions. One is a 30-minutes daily news program and the other is a weekly radio magazine. The first combines pieces collected among all 13 members and the latter turns each week under the responsibility of one of the radio stations.

“The communication in this large region that is the Amazon, where radio stations are isolated here and there, we thought that it was important to gather, to create a chain, a network, where, from its bases, the Amazon could talk to the Amazon. Where Roraima listens to what is happening in Acre, Acre listens to what is happening in Santarém, Santarém listens to what is happening in Belém etc16. In this way, we will give importance to the popular fighters that confront the issues of Amazon, the issues regarding human rights, environment, cultural values of our region. It is the Amazon people experiencing themselves speaking.” (Pereira Rodrigues, 2013)

But getting the permission is just the first hard step for a community radio or television project. According to the law that rules community radio stations in Brazil, this kind of initiative cannot have any commercial activity, which includes advertising. They must survive from donations and what most of them call as cultural support, that is a kind of sponsorship coming from private actors – i.e., not so far from advertising. Lima & Lopes argues that the public policy in the sector ends up in more exclusion, for making even harder the access to the right to communication (Lima & Lopes, O coronelismo eletrônico de novo tipo (1999-2004), 2007). For Sampaio, after a long wait, “the legalization is incomplete”, because it does not provide community radio stations with the same rights as other radio stations and the government, who is responsible for the policy, does not support the activity neither.

“If the government gave a tenth of what it gives for commercial radios (in advertising), the community radio stations could survive better and the information concerning public policies would reach easily the correct audience.” (Sampaio, 2014)

In Florânia (RN), having a radio station was an old dream of the population, but it only came true after a mobilization led by the Catholic Church in the beginning of the years 2000. A priest who was also a lawyer and a deputy helped to move on the process for getting a permission and the community worked hard in order to collect the money needed for buying the equipment. According to Tercio, director of Rádio Ibiapina, the legal procedures went relatively well, counting on the political position of the priest. The challenge of financial maintenance is nevertheless hard.

From the analysis of the cases, it can be said that it is true that the passage to digital platforms via web radio stations and web TVs, for instance, can take over the barrier of legal permissions and expensive equipment. This is something that was frequently mentioned as an advance in the reports of experiences, such as the one presented by coordinators of Rádio Cantareira FM, in the city of São Paulo (SP):

"Communication via radio-web extends the voice of the community since the community radio legislation limits coverage to a radius of 3 km, antenna up to 30 feet tall and 25 watts of power. Another complicating of the law is the limitation of only one frequency channel for community radio stations by county. In this context the web radio breaks certain barriers of community broadcasting legislation and reaches other cities, states and countries." (Rosembach & Zottis, 2013)

Media actors praised the multiple advantages of moving to web radios and web TVs, many of them looking at it as a trend for reaching young people with their smart phones. Again, it is clear that the digital resources can bring solutions for the production process, but there is still a paradox concerning the access, as discussed above. If it is true that popular media will be able to reach audiences out of their niches, structural limitations – mainly low or any internet connection – may still limit the access to their main public in the grassroots.

The hope of “lumières”

Even if when taking into account the existence and relevance of counterpublics, for François and Neveu, the notion of public sphere is related to a common point of reference, where opinions are publicly exposed, role that can be played by Parliaments or the media, for instance (François & Neveu, 1999, p. 48). For Muhlmann, the question about how media keep their role as a mediation between the individual and the community is the very question of democracy (Muhlmann, 2004, p. 22). However, according to several of the actors interviewed during the research, this mediation is compromised with a distance from the reality and a masked partiality. They justify their practice as a mechanism for confronting both stereotypes produced by mainstream media and for introducing new issues in the debate. Some of the actors declare an open interest in interfering in the dominant worldview. Igor Santos, former member of the national communication team of MST, explained the importance of taking part in the initiative of producing the newspaper Brasil de Fato17, speaking mainly about its new edition, distributed freely in metro stations of many Brazilian capital cities.

“In instruments such as Brasil de Fato, what we want to discuss is what we call a popular project for Brazil. (…) We want to vocalize a project of structural transformation of our country, where one of the elements is the agrarian reform. (…) Before, in the MST, the enemy of MST and of the agrarian reform was the farmer, with his hat, his boots dirty with mud, his belt and his employees, who protected his land, that he used as an equity reserve and for real estate speculation. (…) This farmer was frequently associated to the ‘coronelismo’, to the worst political methods, to authoritarianism. In the last period, what have we got? A process in which transnational companies, Monsanto, Bunge, Cargill, Syngenta, come to Brazil and get associated to capitalist farmers, establishing a new model of production in the agriculture, which is the agribusiness. (…) Then, the society, because of the power of agribusiness over media, with advertisings that created a perspective that the agribusiness is modern, that it produces, it exports, it supports the Brazilian economy; the society looks to agribusiness and say ‘it is good’. Now those who are old-fashioned are the ones fighting for redistributing the land, those who do not produce anything, because the media do not give any space for diffusing our production experiences. (…) So, today, we have in the MST a role that is exactly that of stimulating this process of struggle and organization of the whole Brazilian society. That is why the newspaper Brasil de Fato is so important, because it is fundamental in this process of upgrading the level of understanding of society about the need of making huge structural reforms. And, inside this structural reforms, we will fight for the agrarian reform. (Santos I. F., 2013)

Some of the initiatives visited included a media relations strategy in their practices, in order to offer to mainstream media different angles about their subject of struggle or their communities. Francisca Rodrigues and Keli Gois, journalists working in the Agência de Notícias de Paraisópolis, in the city of São Paulo (SP), Southeast region, declared that they feel responsible for every good new that appears in the mainstream media about the neighborhood of Paraisópolis. They guide journalists searching for information and they also propose topics for them (Rodrigues & Gois, 2014). The MST also has an intense media relations work since de beginning of the years 2000. But, as other social groups, they believe in the importance of creating their own media and enlarging the possibilities of direct dialogue with society. They are challenging what Bernard Cassen considers as an illusion, that is the belief that mainstream media will open space for plurality and diversity (Lima V. A., 2006).

Mídia Ninja and Coletivo Nigéria are two initiatives that could be called as born digital. During the demonstrations of June 2013, they turned up as alternative sources of information, diffusing contents directly from the streets. Both groups claim to have among their objectives increasing the level of debate in the society and recovering the voice of social movements (Vilela, 2013) (Gurjão & Rocha, 2013). Their emergence in such an iconic event contributed to bring light to a debate around the communication and the media in the country as a democratic issue (Suzina, 2014).

These actors also trust in the plurality of information in order to develop more critical audiences. They argue that people can build a better opinion if confronted to several perspectives about the same issue.

“We have a side, but we want to show all the sides and, from showing both sides, I think you end up by making that people who watch it end up by seeing the incoherencies. The person herself (identifies) which (side) is less incoherent, which one is more coherent.” (Gurjão & Rocha, 2013)

In his recent writings, Jürgen Habermas talks about the inclusion of mass audiences in the public sphere as a mechanism for regulating the power structure in the latter. And although the author keeps his confidence in the “truth-tracking potential of political deliberation” as a resource to “generate legitimacy through a procedure of opinion and will formation” (Habermas, 2006, p. 413), he does points out to its fragilities. For him, contemporary western countries display an increasing volume of political communication but it does not refer directly to features of deliberation, such as interaction between participants, collective decision or egalitarian exchange of claims and opinions.

Popular media actors propose a progress of general awareness through the increase in the number of worldviews offered to the audiences. The digital world provides opportunities for so many as possible actors to put their perspectives forward online. There is a question for further analysis about the capacity of processes triggered by groups such as Mídia Ninja and Nigéria, or media outlets such as Brasil de Fato, because of their connections to social movements, to represent collective images in the dominant public sphere. Some of the actors interviewed already celebrate an influence in the mainstream media agenda (Rodrigues & Gois, 2014), considering the force of massive diffusion allowed by digital platforms (Vilela, 2013). Even if the character of collective deliberation may still configure a desired horizon, the sole ability of getting represented in the public sphere seems to constitute a step forward for social movements and communities.

Final considerations

Two main general conclusions may be taken from this empirical study. From one side, the cases pose an important question concerning the capability of including publics, specially marginalized ones, in the communication process. From the other side, they also confirm that the use of digital resources pushes the enlargement of access to information.

The first question is, therefore, if there is a real impact of the use of digital resources in the relationships inside the communities. Even if the quality of production can be improved, it is not clear if digital technologies concretely affect the way members of communities and movements take part in this process. Cardon talks about “porous borders” between the two sides of Internet, one regarding interpersonal conversations and the other concerning large diffusion of information (Cardon, 2010, p. 9). The cases analyzed reveal a strong path built around the informational face and a long way to run towards the communicational one (Barranquero & Sáez Baeza, 2010). Considering the context of inequalities in Brazil, digital and analogic media outlets must be deployed in order to mobilize and reach local and national publics.

Regarding the enlargement of access to information, it has two faces, considering popular media practices. One face highlights the possibility of improving media productions by the access to contents and the possibility of sharing productions. It is relevant, because it allows popular media actors to get information they would not access before or would need to pay a lot to do so. The other face shows the possibility of upgrading popular sources of information, meaning that popular media becomes a relevant actor in the media sphere as a producer of information – even if in still unequal conditions. As proposed by Cardon, “the emergence of amateurs in the public space enlarge considerably the perimeter of the democratic debate” (Cardon, 2010, p. 10). This may be seen as a progress while it democratizes at least the struggle for discursive representativeness.

On the other side, believing that connecting does not necessarily mean exchange or deliberation, it is important to consider how the enlargement of opportunities of speaking (Habermas, 2012) is translated into or contributes to collective and political action. At the same time, as the idea of media society associates participation with the capacity of elaborating and diffusing discourses, it is important to raise a question concerning what Dominique Wolton considers as the normative ideal of communication, which is connectivity. This author argues that in contemporary societies, “being able to get in contact, to be informed, to learn, to interact are in fact forms of action” (Wolton, 2005, p. 28), that the possibility of getting connected presupposes that everything can be discussed. But as Habermas, he recalls that even if communication can raise public speaking, reaching connectivity does not mean necessarily promoting exchange.

Venício A. de Lima says that, in Brazil, despite the development of information and communication technologies and the growing use of digital media, the “old media”, as he names the traditional mass media, still keep the “monopoly of visibility”, of “turning things public” (Lima V. A., 2013). Social movements and activists have been trying to change this situation for years. The enlargement of audiences can increase the general visibility of these social groups and their issues. Here again, there is a link to the power of arguing and to the aspiration of influencing the media setting and the debate in the society. But the main evidence coming from the research suggests that it is in the articulation between traditional forms of popular media and new approaches using the digital culture that new opportunities can be built. Just as proposed by Pleyers,

“it is necessary to go beyond the binary opposition between the "virtual" world of cyber activism and the "real" world of mobilizations in the streets and in the squares. Online activism and local roots, global connections and national frameworks, alternative media practices and references to the mass media are articulated rather than opposed”. (Pleyers, 2013/5, p. 10)

In one hand, the use of digital resources has the potential to take over some barriers historically confronted by popular media, such as the cost of production, the access to sources of information and the conditions for media ownership. There is also evidence that the access to internet may be easing the opportunity of reaching new audiences. On the other hand, digital resources can also pose another dimension for the gaps already present in the field, such as inequalities related to the access to resources, discursive competencies and participatory processes.

This empirical study suggests that overcoming inequalities is not enough to take over asymmetries. The full parity of participation demands strong changes which involves structural improvements, but also developments concerning the inclusion and the recognition of alternative voices in the public debate.

Bibliographical References

ANDI, A. N. (2014). Análise de cobertura: A imprensa brasileira e as organizações da sociedade civil. ANDI. [ Links ]

Barbero, J. M. (2001). Reconfiguraciones comunicativas de lo público. Anàlisi(26), 71-88.

Barranquero, A., & Sáez Baeza, C. (2010). Comunicación alternativa y comunicación para el cambio social democrático: sujetos y objetos invisibles en la enseñanza de las teorías de la comunicación. Congreso Internacional AE-IC Málaga 2010 - Comunicación y desarrollo en la era digital, (pp. 1-25).

Berti, O. (2016). Debate. Encontro Anual do COMUNI. São Bernardo do Campo, SP: Umesp.

Bourdieu, P. (1979). La distinction. Critique social du jugement. Les Éditions de Minuit: France. [ Links ]

Cardon, D. (2010). La démocratie Internet. Paris: Seuil. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2013). Communication Power (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Dahl, R. (2001). Sobre a democracia. Brasília: Editora da Universidade de Brasília. [ Links ]

Dahl, R. A. (2005). Poliarquia: participação e oposição (1ª edição, 1ª reimpressão ed.). São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo. [ Links ]

Diniz, A., & Marope, J. P. (2013, October 23). Rádio Fundação Casagrande. (A. C. SUZINA, Interviewer)

Dornelles, B. (2007). Divergências conceituais em torno da comunicação popular e comunitária na América Latina. e-compos: Revista da Associação Nacional dos Programas de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação, 1-18. [ Links ]

Ekman, P. (Director). (2009). Levante sua voz (Motion Picture).

Festa, R. (1984). Comunicação popular e alternativa: a realidade e as utopias. Dissertação (Mestrado em Comunicação Social), 290. São Bernardo do Campo: Instituto Metodista de Ensino Superior.

François, B., & Neveu, É. (1999). Introduction: Pour une sociologie politique des espaces publics contemporains. Em B. FRANÇOIS, & É. NEVEU, Espaces publics mosaïques. Acteurs, arènes et rhétoriques des débats publics contemporains. (pp. 13-58). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Fraser, N. (1992). Rethinking the Public Sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. In C. CALHOUN, Habermas and the Public Sphere (pp. 109-142). Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: The MIT Press.

Fraser, N. (2010). Reframing justice in a globalizing world. In N. FRASER, Scales of justice. Reimagining political space in a globalizing world (pp. 12-29). New York: Columbia University Press.

Fuser, B. (2013, October 28). Jornal de Chiador. (A. C. SUZINA, Interviewer)

Fuser, B., & Ferreira, R. G. (2013). Limites e Perspectivas da Comunicação Cidadã em Chiador, MG. 8º Mutirão Brasileiro de Comunicação. Natal (RN).

Gimenez, G. (1984). Notas para uma teoría de la comunicación popular. Em Que es la comunicación popular y alternativa?: Dos documentos para discusión (2nd ed., Vol. 1). ECO Servicio de documentación: comunicación y solidariedad.

Gonçalves, C. V. (2013). Em Itapipoca "Web Rádio São Francisco.com" comunica, forma e divulga. 8º Mutirão Brasileiro de Comunicação. Natal (RN).

González, J. A. (1990). Sociología de las culturas subalternas. Mexico: UABC. [ Links ]

Gurjão, Y., & Rocha, P. (2013, November 04). Coletivo Nigéria. (A. C. Suzina, Interviewer)

Habermas, J. (2006). Political Communication in Media Society: Does Democracy Still Enjoy an Epistemic Dimension? The Impact of Normative Theory on Empirical Research. Communication Theory, 16, 411-426. [ Links ]

Habermas, J. (2012). Teoria do Agir Comunicativo - Tomo 1: Racionalidade da ação e racionalização social. São Paulo: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Honneth, A. (1995). The struggle for recognition. The moral grammar of social conflicts. Oxford, UK: Polity Press. [ Links ]

IBGE, I. B. (2013). Síntese de Indicadores Sociais. Uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão. [ Links ]

Jr, J., & Tercio, E. (2013, October 25). Rádio Ibiapina. (A. C. SUZINA, Interviewer)

Kaufmann, J.-C. (1996). L'entretien compréhensif. Paris: Nathan. [ Links ]

Lara, R. S., & Gheller, S. (2013). Webradio Migrantes: Canais em português e espanhol dão visibilidade para os coletivos de imigrantes latino-americanos. 8º Mutirão Brasileiro de Comunicação. Natal (RN).

Lima, V. A. (2006). Uma iniciativa fundamental. In I. C. Social, Vozes da Democracia: histórias da comunicação na redemocratização do Brasil (pp. 12-15). São Paulo: Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo; INTERVOZES: Coletivo Brasil de Comunicação Social. [ Links ]

Lima, V. A. (2013). Mídia, rebeldia urbana e crise de representação. Em E. Maricato (et al), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as manifestações que tomaram as ruas do Brasil (pp. 89-94). São Paulo: Boitempo : Carta Maior.

Lima, V. A., & Lopes, C. A. (26 de June de 2007). O coronelismo eletrônico de novo tipo (1999-2004). Fonte: Observatório da Imprensa: http://observatoriodaimprensa.com.br/interesse-publico/o-coronelismo-eletronico-de-novo-tipo-19992004/

Marinho Jr., L. (2013, October 28). Jornal Fala, Mãe Luiza. (A. C. SUZINA, Interviewer)

Miguel, L. F. (2012, December 06-07). Autorização e accountability na representação democrática. Paper apresentado no II Colóqui Internacional de Teoria Política. São Paulo.

Miguel, L. F., Biroli, F., & Duailibe, K. (2013). O lugar do pobre no jornalismo brasileiro. 5º Congresso da Associação Brasileira de Pesquisadores em Comunicação Política. Curitiba, PR.

Muhlmann, G. (2004). Du journalisme en démocratie. Paris: Éditions Payot & Rivages. [ Links ]

Otre, M. A. (2015). A pesquisa acadêmica sobre comunicação popular, alternativa e comunitária no Brasil: análise de dissertações e teses produzidas em programas de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação entre 1972-2012. Tese (Doutorado em Comunicação Social). São Bernardo do Campo: Instituto Metodista de Ensino Superior.

Paiva, R., Malerba, J. P., & Custódio, L. (2013). "Comunidade gerativa" e "comunidade de afeto": Propostas conceituais para estudos comparativos de comunicação comunitária. Revista Interamericana de Comunicação Midiática, 12(24), 244-261. [ Links ]

Pastoral da Comunicação da Arquidiocese de Cascavel – Paraná. (2013). Revista Catedral. 8º Mutirão Brasileiro de Comunicação. Natal (RN).

Pastoral de Comunicação da Arquidiocese de Salvador. (2013). Portal da Arquidiocese de Salvador. 8º Mutirão Brasileiro de Comunicação. Natal (RN).

Pereira Rodrigues, R. L. (2013, October 30). Rede de Notícias da Amazônia. (A. C. Suzina, Interviewer)

Peruzzo, C. M. (1998). Comunicação nos Movimentos Populares. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Peruzzo, C. M. (2005). Internet e democracia comunicacional: entre os entraves, utopias e o direito à comunicação. In J. Marques de Melo, & L. Sathler, Direitos à Comunicação na Sociedade da Informação (pp. 267-288). São Bernardo do Campo, SP: UMESP.

Peruzzo, C. M. (2008). Conceitos de comunicação popular, alternativa e comunitária revisitados. Reelaborações no setor. Palabra Clave, 11(2), 367-379. [ Links ]

Piscitelli, A. (1996). "Sexo tropical": Comentários sobre gênero e "raça" em alguns textos da mídia brasileira. Cadernos Pagu, 6-7, 9-34. [ Links ]

Pleyers, G. (2013/5). Présentation. Réseaux(181), 9-21. [ Links ]

Ramalho, K. (2014, May 09). Núcleo de Comunicação Comunitária São Miguel no Ar. (A. C. SUZINA, Interviewer)

Rodrigues, F., & Gois, K. (2014, May 07). Espaço do Povo. (A. C. SUZINA, Interviewer)

Rosembach, C. J., & Zottis, J. (2013). Comunicação Comunitária Alternativa. 8º Mutirão Brasileiro de Comunicação. Natal (RN).

Sampaio, K. (2014, May 06-07). Rádio Nova Paraisópolis. (A. C. Suzina, Interviewer)

Santos, I. F. (2013, October 18). Jornal do MST. (A. C. SUZINA, Interviewer)

Santos, J. (2014, May 07). Coordinator, Agência de Notícias Paraisópolis. (A. C. SUZINA, Interviewer)

Santos, J. V., & Sena, E. F. (2013). Rede de notícias da Amazônia: O rádio ligando a Amazônia e aproximando seus habitantes. 8º Mutirão Brasileiro de Comunicação. Natal (RN).

Santos, L. J. (Jan-Jul/2009). A construção do feminino negro no jornalismo de revista brasileiro. Caderno Espaço Feminino, 21(1), 167-179. [ Links ]

Serpa, A. (2013). L'univers des radios communautaires à Salvador de Bahia. Brésil(s) - Sciences Humaines et Sociales. Dossier: Hétérotopies urbaines, 3, 89-108. [ Links ]

Sousa Santos, B. d. (2007). Beyond abyssal thinking: from global lines to ecologies of knowledges. Review.

Suzina, A. C. (2014). Which media for improving democracy? 2014 ECPR Graduate Student Conference. Innsbruck, Austria.

Suzina, A. C. (2015). Mais conectados, mais comuns? Recursos digitais nas experiências midiáticas apresentadas no 8º Mutirão Brasileiro de Comunicação. In C. M. Peruzzo, & M. A. Otre, Comunicação Popular, Comunitária e Alternativa no Brasil. Sinais de resistência e de construção da cidadania (pp. 222-245). São Bernardo do Campo: UMESP. [ Links ]

TV Cultura, F. P. (2013, August 05). Programa Roda Viva. São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil.

Unesco. (2014). Tendencias mundiales en libertad de expresión y desarrollo de los medios: Situación regional en América Latina y el Caribe. Montevideo, Uruguay: Oficina Regional de Ciencias de la UNESCO para América Latina y el Caribe, Sector Comunicación e Información.

Unesco. (2014). World trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development. pARIS: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Vilela, R. (2013, October 18). Mídia Ninja. (A. C. Suzina, Interviewer)

Weingrill, N. (2014, May 10). Énois Inteligência Jovem. (A. C. Suzina, Interviewer)

White, D. M. (1950). The "Gate Keeper": A case study in the selection of news. Journalism Quarterly, 383-390.

Wolton, D. (2005). Le siècle de la communication. In D. Wolton, Il faut sauver la communication. Paris: Éditions Flammarion. [ Links ]

NOTES

1 We are using the term popular according to its Latin-American approach. Popular in comunicación popular, in Spanish, and comunicação popular, in Portuguese, refer to the culture of the so-called popular classes in Latin America – which includes indigenous people, those living in peripheries and suburbs, campesinos and all groups that are excluded from the dominant elite culture – who use media outlets to produce or highlight a narrative opposed to a dominant one (González, 1990; Peruzzo, 2008). It also and mainly refers to practices searching for the emancipation and the improvement of life conditions of these groups (Gimenez, 1984) (Festa, 1984) (Otre, 2015).

2 According to the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), in 2012, the 10% of the Brazilian population with the lowest incomes got 1,1% of the total income, while the 10% with the highest incomes got 41,9% of it. The study affirms that even if the participation of the individuals in the national income has improved, this change was not enough to substantially modify the framework of inequalities in the country. (IBGE, 2013)

3 The name NINJA stands for Narrativas Independentes, Jornalismo e Ação and the initiative consists of a network of mainly young people spread all over the country, who produce and broadcast information through a webpage on Facebook. During the demonstrations in 2013, they went to the streets with cameras and smartphones recording and broadcasting everything that crossed their path – they frequently used live and long transmissions.

4 The Fundação Casa Grande, in the city of Nova Olinda (Ceará), Northeast Region, is an NGO that promotes access to culture, working mainly with children and young people. The city has around 15.000 inhabitants and is placed in a very dry and poor region of the country. The NGO maintains an educative radio station, operated by the children.

5 Alemberg Quindins is the founder and current president of the Fundação Casa Grande, in Nova Olinda, Ceará

6 The Ibiapina community radio station is the only medium of the city of Florânia, Rio Grande do Norte, which has around 9.000 inhabitants and is situated in one of the driest regions of the Brazilian Northeast region.

7 Although all initiatives enrolled in the first group were still active in May 2016, the observations made in this article refer to the situation of these cases in 2013-2014. Concerning the second group, the analysis is based on descriptions made by the actors in 2013 and there was no follow-up to confirm if they are still active.

8 The Rede de Notícias da Amazônia is a network of 15 community and catholic radio stations that share contents and produces regional programs about the reality in the Amazon Region.

9 Coletivo Nigéria is an entrepreneurship of four young journalists, located in Fortaleza, Ceará, in the Northeast region. The initiative has two faces. One is a video production house focused on the needs of social movements and NGOs. The other, that is sustained by the first one, is an alternative medium, described by its leaders as a mix between journalism and activism. They also went out to the streets to follow up the demonstrations in 2013 and get alternative information in relation to what mainstream media were showing.

10 Professionals meaning, in this case, people having followed and concluded an academic program in the area of communication studies.

11 This initiative is situated in the neighborhood of São Miguel Paulista, in the east of the city of São Paulo. Its three districts occupy a surface of 24Km2 and shelter around 400.000 people. The Núcleo de Comunicação was created in 2007 under the sponsorship of a corporate foundation. It mobilizes youth and local leaders in the production of a set of community media, including newspapers, street radio and video, and blogs.

12 Depending on the source, this number can fall down to six families (Vieira Jr., 2007).

13 In Brazil, the permission for radio and TV broadcasting is regulated by the Ministério das Comunicações. Everyone interested must pass through a process with legal and technical requirements in order to be allowed for developing the services. The Agência Nacional de Telecomunicações (ANATEL) is responsible for controlling and renewing the use of permissions.

14 Around 250.000 people live in this community of 21km2.

15 The neighborhood of Paraisópolis is considered as the second largest slum of the city of São Paulo, with a population of 56.000-100.000 people (the number varies according to different sources).

16 Roraima, Acre, Santarém and Belém are names of places in the Amazon region.

17 The MST is the social movement of the workers without land, who fights for a better distribution of agricultural lands in Brazil since the 1980s. It develops a large number of media. Brasil de Fato is a newspaper build up with other social actors. Its new version, starting in 2013, is a regional tabloid freely distributed in several capital cities of the country.