Introduction

Uterine rupture in pregnancy is a rare complication. Most cases occur during labor in women with previous uterine surgery but it can also occur during pregnancy and in women with an unscarred uterus1), (2), (3.

Risk factors include previous uterine rupture, previous hysterotomy, high parity, fetal macrosomia and multiple gestation4), (5. Uterine rupture can be associated with severe hemorrhage, hysterectomy and death or morbidity to both mother and fetus6. We report a case of uterine rupture at a 26 weeks twins’ gestation that outlines the paramount necessity to correctly diagnose this condition.

Case report

A 32-year-old caucasian primigravid woman, pregnant of 25 weeks spontaneous dichorionic twins’ gestation was admitted to our emergency department with mild-to-moderate diffuse and intermittent abdominal pain and urinary frequency that started the previous day.

Two years before she was referred to our department due to pelvic pain and hypogastric distension. She was submitted to a laparoscopic myomectomy after the diagnosis of a subserous FIGO type 5 myoma six centimetres of diameter was made. During the procedure, the uterine cavity remained intact since the myoma excision did not reach the uterine mucosa and the uterine incision was closed using a multilayer suture technique. No post-operatory complications were reported. She had no other prior relevant medical or surgical history.

At admission in our emergency department, she showed normal vital signs (apyrexia, normotension) and the abdomen was only mildly tender in the hypogastrium. Gynecologic examination presented no signs of infection or blood loss and a non-dilated cervix. Ultrasonographic cervical-length was 40 mm. Transabdominal ultrasound revealed a pregnant uterus of normal size for gestational age and two intrauterine fetuses with good vitality and normal heartrates. Both placentas and amniotic fluids were normal. Analytic blood assessment was normal. Urine samples showed leukocytes, blood and nitrites, signs of infection. Since there was partial relief of pain after analgesics (paracetamol 1 g intravenously), the patient was discharged with antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin and clavulanic acid) for a urinary tract infection.

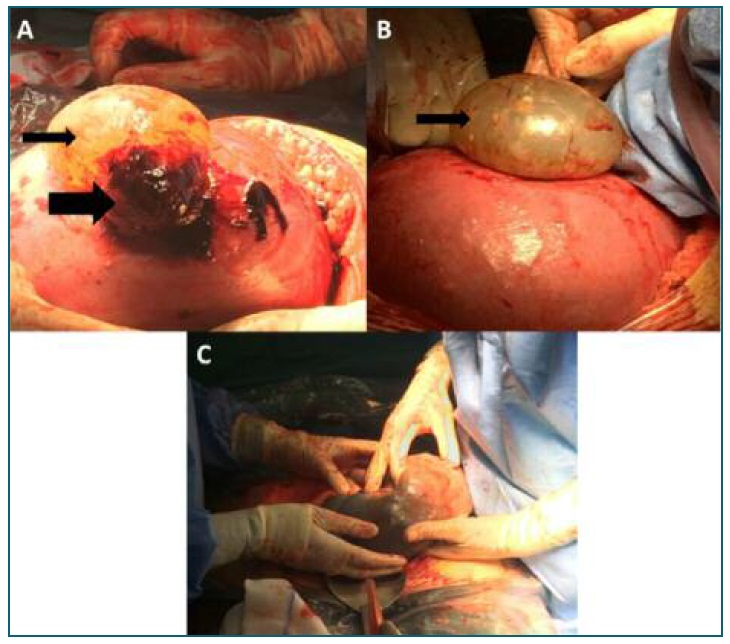

A week later, she was re-admitted due to worsening diffuse abdominal pain, diarrhea and biliary vomiting. Vital signs were normal - blood pressure (BP) 132/67 mmHg, heart rate (HR) 92 bpm, auricular temperature 36.2oC. The abdomen was soft, slightly tender in the right iliac fossa, with no guarding. Gynecologic examination was normal, cervix was non-dilated and tocogram registered no contractions. Ultrasound scan revealed a gravid uterus with a compatible size for a 26 weeks twin gestation. Both fetuses presented with good vitality and normal heart rates. The placentas had no signs of abruption and both amniotic sacs had adequate amniotic fluid. A moderate amount of fluid in the abdomen was identified that presented a slight echogenicity and disperse images suggestive of small clots, rising suspicion to an hemoperitoneum. Uterine wall appeared intact and the adnexa was not identifiable. Laboratory blood evaluation revealed a hemoglobin level of 10.7 g/dl, platelet count 158.000 x 109/L, no leukocytosis or neutrophilia, DHL was normal, as was renal and hepatic functions, PCR was within normal range. The condition was stable and the fetuses showed no signs of distress. However, since there was possibly presence blood in the abdominal cavity and a future necessity of a cesarean section, the patient was put under close observation and started on corticotherapy for fetal pulmonary maturation. For better evaluation, two large-bore venous catheters were placed as was a urinary catheter for urinary debit assessment. During this time, the patient developed tachycardia (HR 141 bpm), hypotension (BP 62/41 mmHg) and decreased urinary output. Repeated blood samples revealed a fall in hemoglobin level of 2.4 g/dl in eleven hours (Hg 8.3 g/dL). On suspicion of ongoing intra-abdominal bleeding of unknown origin, an emergency diagnostic laparotomy was performed. A large amount of blood with organized clots was found in the abdomen. A uterine rupture measuring five centimeters was identified at the fundus of the uterus (Figure 1) with protrusion of intact amniotic sac and placental border with active mild-to-moderate bleeding. A corporal cesarean section was performed. The first neonate (closer to the uterine rupture) was born with 840 g and an Apgar score of 4/6 and the second with 815 g and an Apgar score of 5/5. After the babies were delivered, the site of rupture was revised, and it was compatible with the probable location of the previous uterine suture (of the laparoscopic myomectomy). A double layer suture using Vicryl 1/0 was performed and the hemorrhage was controlled, with no need for a hysterectomy. Intraoperatively the blood loss was 2500 ml and four units of packed red blood cells were transfused perioperative.

FIGURE 1 (A) and (B) A 5 cm uterine fundus rupture with protrusion of intact amniotic sac (thin arrow). Active mild-to-moderate bleeding from the placental border (thick arrow). (C) Extraction of the fetus closer to the uterine rupture (first fetus), fetus inside amniotic sac.

There were no other puerperal complications and the patient was discharged on the fifth day postpartum. The neonates died during the first day of life, secondary to complications associated with extreme premature birth.

Discussion

Abdominal pain in pregnancy is a common symptom and it can have several causes, related or non-related with the gestation7. Pregnancy related causes include physiologic changes, pre-term labor, placental abruption, corioamnionitis, pre-eclampsia, HELLP syndrome, acute fatty liver and uterine rupture8), (9. It can also arise from gynecological pathology as is the case of ovarian torsion, inflammatory pelvic disease, or ovarian cyst rupture8), (9. However, a variety of non-pregnancy-related causes are still possible and must be in mind, like biliary disease, appendicitis, pyelonephritis or nephrolithiasis and gastroenteritis7. The goal in the evaluation of these patients is to quickly identify those who have a critical etiology for their pain.

Life-threatening conditions, such as uterine rupture, may have insidious or catastrophic presentations, depending on the uterine site and size of the rupture5), (10. Uterine rupture has unspecific clinical manifestations and, in most cases, the only sign is fetal distress. Other signs and symptoms that might be present include constant and acute abdominal pain, signs of peritoneal irritation, uterine hypersensitivity, vaginal bleeding, decreased or absence of uterine contractions, changes in the shape of the uterus or in the fetal presentation and maternal tachycardia and hypotension11.

In this clinical case, the patient presented two identifiable risk factors for uterine rupture: previous uterine surgery and a multiple gestation. However, the uterine rupture did not present the “typical” characteristics since there was no sign of fetal distress until vary late in the development of the condition where the mother was already tachycardic and hypotensive. Also, even though the pain was constant it did not have an acute onset and there was no vaginal bleeding or signs of peritoneal irritation. Conceivably, the early abdominal pain, a week before, could have already been an initial sign of uterine rupture, although it is not possible to affirm when the rupture occurred. Probably the amniotic sac prolapsed through the rupture site created a tamponade effect, controlling the haemorrhage and causing more insidious symptoms.

In 2008 three cases of uterine rupture were described where the patients had been assessed a few days earlier for appendicitis, urinary tract infection and gastroenteritis, similarly to this case report12. This emphasizes the difficulty in establishing the correct diagnosis when the symptoms are nonspecific.

When choosing a treatment for myomas, future childbearing plans are an important factor to consider. Myomectomy is an option and laparoscopic myomectomy seems to be associated with remarkable benefits. Intraoperative strategies to reduce uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies include avoiding the endometrial cavity, proper suturing of the uterine defect, limited use of electrosurgery to reduce devascularization, and prevention of hematoma formation, which may interfere with myometrial wound healing13. There is some controversy whether closure of the myometrium with laparoscopic sutures gives the uterine wall the same strength as laparotomic suturing14. In the present case, one large myoma was excised without opening the uterine mucosa, the uterine wall was closed using a multilayer suture technique, no complications were reported and pregnancy occurred two years after surgery, complying with the current recommendations15.

This case report shows that even with proper selection of patients for myomectomy surgical treatment and appropriate surgical technique, individual characteristics may predispose to uterine rupture. This emphasizes the importance of explaining this risk to women of childbearing age before submitting them to surgery.

Furthermore, as shown in this case report, uterine rupture can be associated with nonspecific symptoms and an insidious presentation, which makes the diagnosis more difficult. Thus, a high index of suspicion is needed to avoid poor outcomes, especially in women with identifiable risk factors.