INTRODUCTION

The term quality of life (QoL) has never been so popular in our country, precisely because of the current moment the world is going through. However, due to its complexity and use in different areas of study, its definitions are presented in varied ways, and several factors are taken as foundations for its definition, carrying with them a subjective, cultural, and historical essence, having as the primary source of information individuals themselves (Araújo & Bós, 2017).

The World Health Organization (WHO) conceptualized QoL as the individual’s perception of their position in life, related to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns (WHO, 1997).

Due to the conceptual dynamism of the term QoL, numerous factors influence its context. Health-related quality of life encompasses the impact of illnesses as well as the various forms of therapeutic interventions which, under the individual’s perception, promote change in their health, whether physical, psychological, social, and/or spiritual (Aguiar et al., 2021).

Pilates Method (PM) appears as a therapeutic intervention model that can contribute to the QoL improvement of its practitioners. Created by the German Joseph Pilates, the method aims to benefit through integration between body and mind, enabling individuals to overcome their limitations and relieve pain and stress (Roh, 2019).

This method principle relies on the execution of integrative movements between body and mind through synchronism between fluidity, concentration, breathing, and muscle contraction (Melo et al., 2020).

Composed of a wide range of exercises that cater to audiences of different age groups and functional profiles, PM aims to stimulate the body to benefit the physical and emotional aspects that impact the quality of life of its practitioners (Vilella, León-Zarceño, & Serrano-Rosa, 2017).

Pilates Method is characterized as a complete activity for working the body as a whole, associating physical and mental conditioning, body awareness, postural correction, strength, and flexibility, which, collectively, contribute to the improvement of muscle imbalances, as well as structural and emotional stability of the individual, favouring a healthier life (Bezerra, Araújo, Elizabeth, & Araújo, 2020).

In recent years, research on PM has intensified alongside the dissemination of the method and the increase in practitioners. The method has been increasingly used as a therapeutic and preventive method, with favourable results for improving the QoL of its adherents (Pereira, Flach, & Haas, 2018).

The benefits for QoL with the practice of PM were related to improvement in levels of depression, anxiety, and pain in a study with patients with fibromyalgia (Cordeiro et al., 2020). However, Kim et al. (2019) observed in their study with patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia that flexibility activities — such as those performed in PM — had lower results in terms of QoL when compared to aerobic activities.

The results achieved through PM can motivate its practitioners and be used as an alternative approach to traditional exercises, such as walking. Vancini, Rayes, Lira, Sarro, and Andrade (2017) found that eight weeks (three sessions/week) of Pilates and aerobic training, with monitored and progressively adjusted intensity, had a positive impact on improving general health, self-esteem, emotional and psychological state, mood, and motivation of practitioners.

In sedentary patients, Leopoldino et al. (2013) found that an increase in QoL through the practice of PM was linked to the improvement of sleep quality of the volunteers. In women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, PM contributed to improving QoL by promoting improvement in functional capacity (Küçükçakir, Altan & Korkmaz, 2013).

A similar result was evidenced in research with individuals diagnosed with chronic low back pain, where the practice of PM increased the practitioners’ QoL by improving their range of motion and pain (Natour, Cazotti, Ribeiro, Baptista, & Jones, 2015). The practice of PM has also contributed to reducing pain and enhancing the range of motion and functional capacity in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, improving patients’ QoL (Mendonça et al., 2013).

Therefore, the choice to carry out a literature systematic review on the influence of PM on the QoL of its practitioners is justified by providing scientific standards. Such standards minimize errors and favour reliable results to synthesize the information provided by different authors in different countries, thus elaborating an important instrument to base the method, health management, and clinical practice (Impellizzeri and Bizzini, 2012).

In this sense, despite varied evidence that indicates the effectiveness of PM for health, the novelty of this study lies in the compilation of information about aspects relating to the influence of PM on the QoL of its practitioners, therefore expanding and updating knowledge about the application of the method and allowing for an expansion of clinical indications.

METHODS

Protocol and registration

This review was developed following the PRISMA 2020 protocol — Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses and was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): number CRD42021273295.

Eligibility criteria

Observational and experimental studies may be included, as long as they investigate the relationship between the practice of the Pilates Method in people over 18 years of age and their QoL, without delimiting dates, in any language or location. Review studies, letters to the editors, qualitative analyses, case studies or book chapters, and studies that included people under 18 years of age will be excluded.

Information sources and research strategy

The search strategy was developed based on the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) list of recommendations (McGowan et al., 2016) and sent to two investigators for review.

The following databases were used (Appendix 1): MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar. The search strategy used for MEDLINE was: (“Pilates Practitioners”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“Young People”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“Old People”[Title/Abstract]) OR (Aged[Title/ Abstract]) OR (Elderly[Title/Abstract]) OR (Young[Title/Abstract]) OR Adult [Title/Abstract] AND (“Pilates”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pilates Training”[Title/Abstract] OR “ Pilates Based Exercises”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pilates based exercises”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pilates Based Exercises”[Title/Abstract] OR “training Pilates”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pilates Method”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Motor activity”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pilates Exercise” [Title/Abstract] OR “Pilates Activity” [Title/Abstract] AND (“Quality of life”[Title/Abstract] OR “Lifestyle”[Title /Abstract] OR “Life Quality”[Title/Abstract] OR “health related quality of life”[Title/Abstract] OR “Health Related Quality”[Title/Abstract] OR “HRQOL”[Title/Abstract]) AND (Observational OR “Observational Study” OR Survey OR “Cross - Sectional” OR “Cross sectional” OR Cohort OR Association OR Relationship OR Correlation).

Searches were initiated and finished in May 2021.

Selection of studies and data extraction

The studies were selected in two phases by two researchers independently (FSAS e LCSA). The studies were selected by title and abstract in the first phase, always following the eligibility criteria. In the second phase, the selected articles were fully read, and a selection was made again to see if they would meet the inclusion criteria.

Afterwards, the two investigators (FSAS e LCSA) met to resolve any disagreement about the selection. A search was also carried out in the bibliographic references of the selected articles to verify any possible studies that could be incorporated into this review. The participation of a third researcher was not necessary, as all differences between the two main ones were resolved.

The characteristics of the selected articles were distributed in three tables, with the following information: Author and year; country of study; sample (n sample, sex, and age); evaluated population, study design, and objective; quality of life assessment instruments and respective scores by domains; method of evaluation of the Pilates practice and its respective results; types of statistical tests used, adjustment variables, main results, and one final question: “What is the influence of PM in improving the QoL of its practitioners?”.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The instrument recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Moola, Munn, & Tufanaru, 2017) for experimental studies was used to assess the risk of bias.

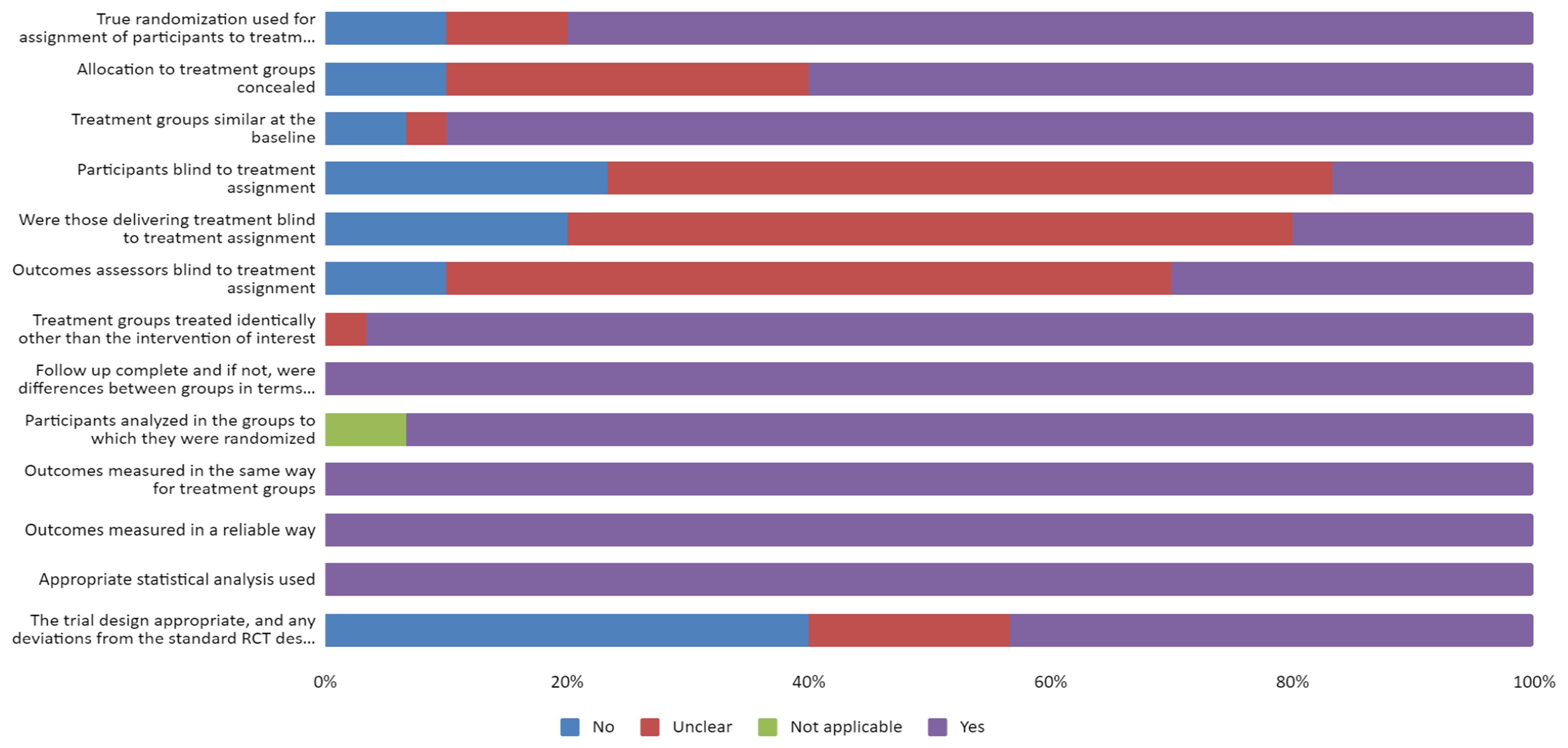

The instrument for experimental studies consists of thirteen questions: “Was true randomization used to assign participants to treatment groups”; “Was assignment to treatment groups hidden”; “Were treatment groups similar at baseline”; “Were participants blinded to treatment assignment”; “Were those delivering treatment blinded to treatment assignment”; “Were outcome assessors blinded to treatment assignment”; “Were treatment groups treated identically beyond the intervention of interest”; “Was it the full follow-up and, otherwise, were the differences between groups in terms of follow-up adequately described and analyzed”; “Were participants analyzed in the groups in which they were randomized”; “Were outcomes measured in the same way for the treatment groups”; “Were results reliably measured”; “Was appropriate statistical analysis used”; “Were the proper trial design, and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups), accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial.”

Questions were answered as “yes”, “no”, “not clear” or “not applicable”. If all answers are “yes” for all items, the risk of bias will be low, and if any item is rated “no,” a high risk of bias is expected. This assessment was not used as an eligibility criterion for the inclusion of articles.

RESULTS

Selection of studies

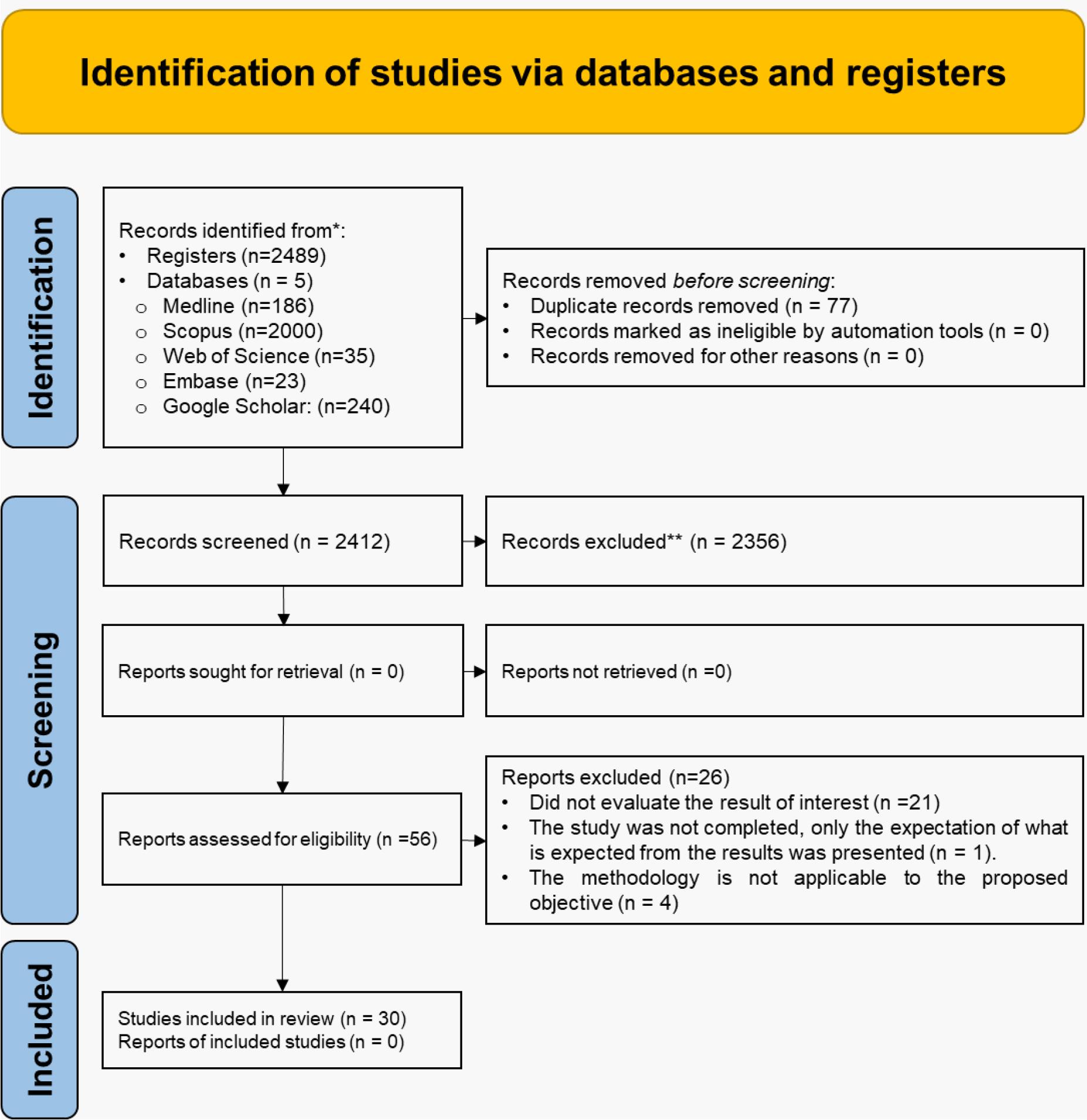

Figure 1 shows the selection steps and the number of final articles included in the review. Appendix 2 shows the excluded articles and the reason for the exclusion (supplementary material).

*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers); **If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

Source: Page et al. (2021).

Figure 1 Flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only. Adapted from PRISMA 2020.

Study characteristics

Table 1 presents the general objective of each study and other characteristics. After the selection steps, 30 articles were selected, which included a control group and a group with the intervention performing PM. The studies were published between 2009 and 2020. The studies were carried out in several countries, and the largest number were carried out in Brazil (n= 10; 33.33%) and Turkey (n= 10; 33.33%). The total sample consisted of 1,624 individuals.

Table 1 Description of included studies.

| Author/Year | Country | Sample (n. sex. age) | Evaluatedpopulation | Study design | Aim of the study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altan, Korkmaz, Bingol, and Gunay (2009) | Turkey | 55. Both Sexes. 28 to 69 years. Mean age: 45.23± 10.73. | People with ankylosing spondylitis | Randomized, prospective, controlled, and single-blind trial. | To investigate the effects of Pilates on pain, functional status, and QoL in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. |

| Angin et al. (2015) | Turkey | 41. Female. Age: 40 - 69 years | Women with postmenopausal osteoporosis | Randomized clinical trial. | To investigate the effects of Clinical Pilates Exercises on BMD, physical performance, and QoL in postmenopausal osteoporosis. |

| Borges et al. (2014) | Brazil | 22. Both sexes. 18 to 65 years | Patients with HTLV-1. | Randomized crossover clinical trial | To assess the effect of Pilates exercises on chronic low back pain in these patients and its impact on QoL. |

| Campos de Oliveira, Gonçalves de Oliveira, Pires-Oliveira (2015) | Brazil | 16. Both sexes. Mean age, 63.62± 1.02 years. | Older adults. | Randomized, controlled, clinical trial | To determine the effects of Pilates on lower leg strength,postural balance and the HRQoL of older adults. |

| Eyigor, Karapolat, Yesil, Uslu, & Durmaz (2010) | Turkey | 52. Female. 18 to 75 years. | Female breast cancer patients. | Randomized controlled trial. | To investigate the impact of Pilates exercises on physical performance, flexibility, fatigue, depression, and QoL in women who had been treated for breast cancer. |

| Gandolfi, Corrente, De Vitta, Gollino, and Mazeto(2012) | Brazil | 40. Female. 60 years and older. | Older Women | Longitudinal prospective study with intervention | To evaluate the effects of the Pilates method on QoL and bone remodelling markers in a group of older women. |

| García-Soidán et al. (2014) | Spain | 99. Both Sexes. Mean age: 47.6± 0.8 years. | Middle-Aged People. | Prospective Experimental Study | To evaluate the effects of a 12-week Pilates exercise program in sedentary, middle-aged individuals |

| Karaman, Yuksel, Kinikli, & Caglar (2017) | Turkey | 46. Both Sexes. 55 to 85 years. | Total knee arthroplasty | Prospective, randomized, controlled study with intervention | To investigate the effect of the addition of Pilates-based exercises to standard exercise programs performed after total knee arthroplasty on QoL and balance. |

| Kheirkhah, Mirsane, Ajorpaz, & Rezaei (2016) | Iran | 60. Both sexes. 18 to 70 years. PG: mean age 40.1± 1.8 years. | Patients onHemodialysis | Clinical trial | To define the effect of Pilates exercise on the QoL of patients on hemodialysis referred to selected hospitals in Kashan. |

| Kofotolis, Kellis, Vlachopoulos, Gouitas, & Theodorakis (2016) | Greece | 101. Female. Age 25–65 years, | Patients with Chronic low back pain | Randomized clinical trial. | To compare the effects of a Pilates program and a trunk strengthening exercise program on functional disability and HRQoL in women with non-specific chronic low back pain. |

| Vécseyné Kovách, Kopkáné Plachy, Bognár, Olvasztóné Balogh, & Barthalos (2013) | Hungary | 54. Both sexes. Mean age 66.4± 6.2 years. | Retired elderly. | Randomly assigned | To measure the effects of Pilates and aqua fitness training on functional fitness and QoL in older individuals. |

| Küçük, Kara, Poyraz, & İdiman (2016) | Turkey | 20. Both Sexes. | Multiple sclerosispatients. | Controlled randomized study. | To determine the effects of clinical Pilates in multiple sclerosis patients. |

| Küçükçakir et al. (2013) | Turkey | 70. Female. 45 to 65 years. | Women with postmenopausal osteoporosis | Randomized, prospective, controlled, and single-blind trial. | To evaluate the effects of the Pilates exercise program on pain, functional status, and QoL in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. |

| Lim and Park (2019) | South Korea. | 90. Both Sexes. 30 to 40 years. | Yoga Community and Korean Pilates Federation participants. | Randomized clinical trial. | To investigate the effect of Pilates and yoga participation on their functional movement and individual health level. |

| Liposcki, da Silva Nagata, Silvano, Zanella, & Schneider (2019) | Brazil | 24. Female. Pilates Group: Mean age: 63.7± 3.3 years. | Sedentary elderly people | Blind, controlled clinical trial | To verify the effects of a Pilates exercise program on the QoL of sedentary elderly people. |

| Medeiros et al. (2020) | Brazil | 42. Female. 18 to 60 years | Women withfibromyalgia. | Clinical, randomized, and blind trial. | To evaluate the effectiveness of the mat Pilates method for improving symptoms in women with fibromyalgia. |

| Natour, Cazotti, Ribeiro, Baptista, and Jones (2015) | Brazil | 60. Both Sexes. 18 to50 years. | Chronic low back pain | Randomized controlled trial | To assess the effectiveness of the Pilates method on patients with chronic non-specific low back pain (LBP). |

| Odynets, Briskin, and Todorova (2019) | Ukraine | 115. Female. 50 and 60 years. | Breast Cancer Surgery Rehabilitation | Randomized, prospective,controlled trial. | To evaluate the effects of different exercise interventions on QoL parameters in breast cancer patients during one year of outpatient rehabilitation. |

| Oliveira, Oliveira, and Pires-Oliveira (2018) | Brazil | 51. Female. 40 to 70 years. | Postmenopausalwomen. | Randomized controlled clinical trial | To compare the effects of Pilates vs whole-body vibration (WBV) on isokinetic muscle strength and QoL in postmenopausal women. |

| Oliveira et al. (2019) | Brazil | 51. Both Sexes. 18 years and older. | Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of Chikungunya fever. | Blind, controlled clinical trial | To evaluate the effects of the Pilates method on the reduction ofpain, improvement of joint function, and QoL of patients with chronic Chikungunya fever. |

| Özyemişci Taşkiran et al. (2014) | Turkey | 58. Both sexes. Mean age 78± 6.8 years. | Elderly living in a nursing home. | Randomized clinical trial. | To investigate whether Pilates and yoga affect QoL and physical performance of elderly subjects living in a nursing home. |

| Rahimimoghadam, Rahemi, Sadat, & Mirbagher Ajorpaz (2018) | Iran | 50. Both sexes. 18 to 65 years. | Patients with chronic kidney diseases | Randomized controlled clinical trial. | To determine the effect of Pilates exercises on the QoL of CKD patients. |

| Rodrigues, Ali Cader, Bento Torres, Oliveira, & Martin Dantas (2010) | Brazil | 52. Female. 60 to 78 years. | Elderly Female | Randomized controlled clinical trial. | To evaluate the effects of the Pilates method on personal autonomy, static balance, and QoL in healthy elderly females. |

| Saltan and Ankarali (2021) | Turkey | 92. Both sexes. 18 to 25 years. PG: Mean age: 18.82± 1.071. | University students. | Randomized controlled trial | To investigate the effects of the Pilates exercise program on HRQoL pain, functional level, and depression status in university students. |

| Surbala Devi et al. (2013) | India | 23. Both Sexes. Mean age: Pilates Group: 57± 5.2 Years; Control Group: 59± 5.5 years. | Sub-Acute Stroke Subjects. | Randomized Controlled | To evaluate the effects of Pilates training on functional balance and QoL in sub-acute Stroke subjects. |

| Surbala Devi, Ratan, Parth, Bhatt, & Vasveliya (2014) | India | 51. Both sexes. PG: mean age: 70.7± 2.7 years. | Elderly. | Blinded prospective randomized controlled. | To compare the effectiveness of PI and CBT in improving functional balance and QoL in elderly individuals. |

| Vancini, Rayes, Lira, Sarro, & Andrade (2017) | Brazil | 63. Both sexes. 18 to 66 years. | Overweight and obese individuals | Randomized blinded and controlled. | To compare the effects of Pilates and walking on QoL, depression, and anxiety levels |

| Yentür, Ataş, Öztürk, & Oskay (2021) | Turkey | 30. Both Sexes. 18 to 65 years. | Rheumatoid arthritis | Randomized clinical trial | To compare the effects of Pilates exercises, aerobic exercises, and combined training, including Pilates with aerobic exercises, on fatigue, depression, aerobic capacity, pain, sleep quality, and QoL. |

| Yucel and Omer (2018) | Turkey | 56. Female. Age: 18 - 65 years. | Women with type 2 diabetes | Randomized clinical trial | To investigate the effects of PBME on glycemic control, anxiety, depression, and QoL in women with type 2 diabetes. |

| Yun et al. (2017) | Korea | 40. Both Sexes. Mean age 63.5± 3.5 | Chronic stroke patients | Randomized clinical trial. | To observe the influence of Pilates training on the QoL in chronic stroke patients. |

ATR: Angle of trunk rotation; BMD: bone mineral density; CBT: Conventional Balance Training; CKD: chronic kidney diseases; HAM/TSP: HTLV-1–associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis; HLTV-1: Human T-cell Lymphotropic Virus 1; HRQoL: Health-related quality of life; JIA: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis; MP: Mat Pilates; PBME: Pilates-based mat exercise; PG: Pilates Group; PI: Pilates intervention; pwMS: persons with multiple sclerosis; QoL: Quality of Life; RT: Resistance Training; TC: Tai Chi Chuan; USA: United States of America.

Results of individual studies

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the relationship between PM and aspects connected to the improvement of the QoL of its practitioners, showing the various instruments used to assess the variables of interest, statistical tests, adjustment variables, and the main outcomes.

Table 2 Instruments used to assess the quality of life and the practice of Pilates and their respective results.

| Author/Year | Qol Instrument | Qol Result-Score | Evaluation method of pilates practice | Pilates practice results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altan et al. (2009) | ASQOL | PG before training: ASQoL: Week 1: 3.7± 4.6;PG after training: Week 12:4± 4.9; Week 24: 4± 4.8. | Three sessions/week. For 1 hour. 12 weeks. | In the Pilates group, ASQoL BASFI, BASMI, BASDAI, and chest expansion scores improved. |

| Angin et al. (2015) | QUALEFFO-41 | PG before training: Pain:77.09± 10.33; DA:89.28± 6.83; HW: 73.14± 11.72; Mobility:84.43± 8.20; SA: 62.01± 12.22; GH:52.05± 9.24; MF:60.20± 10.19. PG after training: Pain:63.18± 12.30; DA:81.60± 13.79; HW: 62.27± 15.47; Mobility: 73.12± 13.22; SA: 39.98± 14.81; GH: 35.07± 12.83; MF: 51.95± 10.09. | Three sessions/week, for 1 hour. 24 weeks | Pilates Exercise effectively increases BMD, QoL, walking distance, and is also beneficial to relieve pain. Physiotherapists can use Pilates Exercises for the subjects with osteoporosis in the clinics. |

| Borges et al. (2014) | SF-36 | PG before training: PI:7.18± 2.35; PF:23.18± 14.88; PRF: 18.18± 31.80; BP: 31.82± 14.75; GHP: 46.36± 24.13; VIT: 23.18± 18.20; SRF: 46.59± 30.15; ERF: 33.36± 42.19; MH: 56.73± 24.71. PG after training: PI: 3.45± 2.54; PF:41.82± 20.16; PRF:72.73± 32.51; BP:60.64± 20.11; GHP: 52.73± 25.73; VIT: 56.36± 22.70; SRF: 69.312± 20.43; ERF: 63.65± 40.71; MH: 69.82± 25.45. | Two sessions/week, for 1 hour. 15 weeks. | To sum up, Pilates proved to be a useful tool for reducing self-reported LBP, which is the most common complaint of patients infected by the HTLV-1 and has a significant impact on their QoL. |

| Campos de Oliveira et al. (2015) | SF-36 - Brazilian version | PG after training: PF:93,4± 10,9; PRF: 93,4± 10,9; Pain: 90.3± 12.4; GHS: 87.2± 11.8; VIT: 90.9± 9.8; SRF: 91.6± 8.7; ERF: 95.8± 16.7; MH: 90.2± 12.7. | Two sessions/week, for 1 hour. 12 weeks. | PG participants showed improved posture and increased HRQL scores. |

| Eyigor et al. (2010) | EORTCQLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ BR23 | PG before training: EORTC QLQ-C30-Functional: 77.07± 14,96; EORTC QLQ-C30 - Symptom: 18.98± 12.18; EORTC QLQ-C30-Global: 70.16± 20.58; EORTC QLQ-C30 BR 23 functional: 77.81± 16.62 EORTC QLQ-C30 BR 23 Symptom: 21.11± 15.28 PG after training: EORTC QLQ-C30-Functional: 83,26± 14,70; EORTC QLQ-C30-Symptom: 20,89± 21,49; EORTC QLQ-C30-Global: 77,02± 21,81; EORTC QLQ-C30 BR 23 functional: 84,39± 10,47; EORTC QLQ-C30 BR 23 Symptom: 17,35± 18,20. | Three sessions/week, for 1 hour. Eight weeks. | After the Pilates sessions, QoL scores improved in group 1, and symptom scores decreased. |

| Gandolfi et al. (2012) | SF-36 | PG before training: PF: 67.50± 18.88; PR: 67.50± 39.82; SF: 46.88± 13.37; ER: 65.00± 45.21; GH:75.50± 9.45; VIT: 68± 21.55; MH: 70.60± 24.36; BP: 51± 6.41; PCS:65.00± 14.39; ECS: 60.83± 19.47; Total: 64± 13.41. PG after training: PF: 86.25± 0.58; PR: 100.00± 0.00; SF: 42.50± 13.69; ER: 100.00± 0.00; GH: 79.25± 6.34; VIT: 82.50± 14.28; MH: 79.80± 19.31; BP: 50.50± 5.10 PCS: 79.70± 3.83; ECS: 74.10± 8.37; Total: 77.60± 4.86 | One session/week, for 50 min. 20 weeks. | The group of women undergoing Pilates showed an improvement in the QoL domains compared to the CG. |

| García-Soidán et al. (2014) | SF-36 | PG before training (M1 - Mean± SE): FC: 77.4± 1.26; PHA: 78.9± 0.86; BP: 77.6± 0.85; GH: 63.3± 0.0,49; VIT: 52.2± 0.48; SA: 72.7± 0.15; EA: 44.2± 0.21; MH: 59.6± 0,10. PG before training (M1 - Mean±SE) FC: 87.6± 1.16; PHA: 86.6± 0.75; BP: 66.1± 0,90; GH: 81.0± 1.51; VIT: 71.0± 0.12; SA: 85.2± 1.30; EA: 75.3± 8,9; MH:73.4± 8.9. | Twelve weeks, two times a week, 1 hour per session. | Those in the Pilates group had an increase in QoL, general physical activity and sleep duration, and a decrease in sleep latency. |

| Karaman et al. (2017) | SF-36 | PG before training: PF: 28.8± 13.8; PRL: 11.8± 26.7; Pain: 16.6± 17.5; GH: 69.3± 17.8; VIT: 36.2± 23.0; SF: 56.6± 38.6; ERL: 17.6± 35.6; MH: 47.8± 23.0; MCS: 38.8± 12.0; PCS: 30.9± 3.8; BBS: 36.9± 4.5. PG after training: PF: 67.6± 18.9; PRL: 64.2± 39.5; Pain: 59.1± 25.2; GH: 81.0± 16.8; VIT: 67.1± 20.4; SF: 81.6± 27.6; ERL: 76.5± 40.4; MH: 76.2± 15.8; MCS: 53.6± 10.4; PCS: 44.2± 7.1; BBS: 50.6± 3.9. | Six weeks after the day of hospital discharge. | Pilates-based exercises performed along with standard exercise programs were more effective for improving balance and QoL than standard exercise programs alone. |

| Kheirkhah et al (2016) | KDQOL SF | PG before training: Health and functioning: Satisfaction:50.4± 15.1; Importance: 48.2± 11.2. Socioeconomic: Satisfaction: 40.2± 14.2; Importance: 50.5± 14.2. Psychospiritual: Satisfaction: 51.8± 12.4; Importance: 50.1± 12.3. Family: Satisfaction: 58.5± 12.2; Importance: 56.5± 13.2. Total QoL: Satisfaction: 48.5± 13.7; Importance: 50.5± 14.1. PG after training: Health and functioning: Satisfaction: 55.8± 13.1; Importance: 53.6± 13.6. Socioeconomic: Satisfaction: 48.9± 13.2; Importance: 58.4± 13.1. Psychospiritual: Satisfaction: 59.6± 13.2; Importance: 60.5± 13.7. Family: Satisfaction: 66.5± 13.2; Importance: 61.5± 13.8. Total QoL: Satisfaction: 60.5± 12.8; Importance: 64.3± 13.6. | Three sessions/weeks. Eight weeks. | Differences were significant between health and functioning, socioeconomic, psycho-spiritual, and family scores in the Pilates group before and after the intervention. |

| Kofotolis et al. (2016) | SF-36 | PG before training: PF: 51.08± 14.58; RP: BP: 38.51± 12.62; GH: VIT: 44.58± 15.03; RM: 11.32± 4.11. PG after training (post 1): PF: 51.08± 14.58; BP: 79.14± 7.93; GH: VIT: 70.32± 9.58; RM: 3.32± 1.78. | Three sessions/week; for 1 hour; 8 weeks. | An 8-week Pilates program improved HRQOL and reduced functional disability more than a trunk strengthening exercise program or controls among women with chronic low back pain. |

| Vécseyné Kovách et al. (2013) | WHOQOL | PG before training: Perception: 8.9± 1.4; Autonomy: 15.55± 2.5; Present, past and future: 14.2± 1.8; Sociability: 14.95± 2.15; Death: 10.7± 4.2; Intimacy: 12.55± 4.6. PG after training: Perception: 10.3± 1.7; Autonomy: 14.3± 2.2; Present, past and future: 13.7± 2.2; Sociability: 15.55± 1.9; Death:10.6± 3.9; Intimacy: 13.1± 3.7. | Three sessions/weeks, four 1 hour. 6 months. | A 6-month intervention program is an appropriate tool to improve the overall physical performance of healthy, inactive older adults, regardless of the type of exercise concerning Pilates or Aquafitness but might improve only some aspects of QOL. |

| Küçük et al. (2016) | MusiQol | PG before training: Total QoL: 28.22± 9.06 PG after training: Total QoL: 23.82± 7.53 | Two sessions/week for 45-60 min. Eight weeks. | In addition to QoL, clinical Pilates improved the participants’ cognitive functions compared with the traditional exercises. |

| Küçükçakir et al. (2013) | SF-36 | PG before training: PF: 58.3± 20.1; PRL:51.7± 35.9; BP: 42.3± 15.5; SF: 61.5± 18.4; MH:57.3± 16.7; ERL: 60± 34.4; VIT:46.8± 20.7; GH: 42.3± 17.6. PG after training (1 year): PF: 85.3± 14; PRL: 88.3± 26; BP: 70.7± 16.2; SF: 76.1± 15.7; MH: 73.9± 16; ERL: 87.8± 28.3; VIT: 68.3± 18.2; GH: 69.5± 11.8; | Two sessions/week. One year. | Our results showed that Pilates exercises might be a safe and effective treatment alternative relative to the QoL in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. |

| Lim and Park (2019) | SF-36 | PG before training adjusted: PF: 865.00± 135.28; RLP: 293.33± 114.27; RLE: 216.67± 98.55; Energy: 207.33± 63.35; EWB: 295.33± 77.31; SF: 125.83± 40.73; Pain: 134.67± 38.82; GH:2 61.67± 87.03; HC: 39.17± 20.43; Total: 2,439.00± 524.88. .PG after training adjusted: PF: 916.68± 18.81; RLP: 366.46± 10.57; RLE: 291.81± 8.20; Energy: 274.92± 6.79; EWB: 378.30± 7.40; SF: 164.74± 3.92; Pain: 169.96± 4.94; GH: 343.62± 11.37; HC: 71.40± 2.87; Total: 2,979.88± 44.67. | Three sessions/week, for 1 hour. Eight weeks. | The participants in the Pilates group had an improvement in the SF-36 domains, functional movement, and individual health. |

| Liposcki et al. (2019) | SF-36 | PG before training: FC: 82.2± 15.4; PHA: 61.1± 46.9; PAIN: 67.0± 22.2; GH: 67.8± 22.5; VIT: 63.3± 23.3; SAS: 81.8± 27.3; EA:74.0± 43.4; MH: 72.8± 18.5. General QoL: 70.8± 23.9. PG after training: FC: 91.6± 14.3; PHA: 92.7± 14.8; PAIN: 95.7± 6.9; GH:8 9.4± 11.2; VIT: 85.5± 13.5; SAS: 97.2± 8.3; EA: 92.6± 22.0; MH: 88.8± 10.5. General QoL: 92.1± 11.2. | Two sessions/week, for 30 min. Six months. | During the study period, there was a significant increase in the QoL of women in the PG (p= 0.00), while the QoL in the CG remained unchanged. |

| Medeiros et al. (2020) | SF-36 | PG T0: RS: 54.2± 21.3; GH: 38.2± 19.2; VIT: 34.6± 17.5; FC: 34.0± 17.1; RP: 23.7± 28.8; EA: 44.4± 46.3; Pain: 33.3± 17.2; MH: 57.5± 21.9. PG T12: RS: 54.2± 21.3; GH: 39.0± 23.6; VIT:43.8± 19.5; FC:43.5± 22.0; RP: 36.2± 38.6; EA: 43.6± 43.6; Pain: 44.9± 18.4; MH: 65.9± 27.8. | Two sessions/week. 12 weeks. | The aspects related to QoL only showed improvement in the mat Pilates group (p< 0.05). |

| Natour et al. (2015) | SF-36 | PG before training: PF: 58.75± 23.69; RP: 42.70± 40.69; BP: 42.91± 21.40; GH: 63.66± 23.3; VIT: 56.04± 21.21; SF: 78.64± 28.18; ER: 78.86± 26.97; MH: 67.06± 21.85. PG after training (t45): PF:63.95± 25.62; RP: 47.37± 40.68; BP: 49.95± 26.79; GH: 62.79± 23.75; VIT: 61.87± 19.27; SF: 83.12± 25.26; ER: 82.20± 25.88; MH: 66.53± 22.97. PG after training (t90): PF: 65.83± 27.96; RP: 49.00± 37.27; BP: 54.45± 23.41; GH: 68.58± 21.92; VIT: 64.58± 21.15; SF: 83.75± 24.51; ER: 80.43± 29.72; MH: 69.30± 21.14. PG after training (t180): PF: 65.41± 28.01; RP: 56.37± 34.77; BP: 52.16± 24.57; GH:65.20± 22.15; VIT: 60.29± 23.41; SF: 86.04± 22.75; ER: 82.64± 24.18; MH: 67.90± 22.05. | Two sessions/week, for 50 minutes. 12 weeks | Patients with LBP can use the Pilates method to improve pain, function, and QoL (functional capacity, pain, and vitality). Moreover, this method has no harmful effects on such patients. |

| Odynets et al. (2019) | FACT | PG before training: PWB:15.33± 0.60; SFWB: 13.08± 0.48; EWB: 12.55± 0.51; FWB:15.04± 0.45; BCS:17.84± 0.51; AS: 8.93± 0.50; Total: 82.80± 2.14. PG after training (6 months): PWB: 19.22± 0.67; SFWB: 14.84± 0.53; EWB: 15.20± 0.51; FWB: 18.00± 0.54; BCS: 21.00± 0.48; AS:11.91± 0.50; Total:100.17± 2.11. PG after training (12 months): PWB: 23.75± 0.49; SFWB: 15.20± 0.48; EWB: 18.82± 0.29; FWB: 20.46± 0.45; BCS: 26.17± 0.40; AS: 16.48± 0.23; Total: 120.91± 1.26. | Three sessions/ week, for one hour. 12 months. | The participants in the Pilates group had an improvement in the FACT: PWB, SFWB; EWB; FWB. |

| Oliveira, Oliveira, nd Pires-Oliveira (2018) | SF-36 | PG before training (Median IQR 25th–75th percentiles):PF: 85 (75–95); RP: 100 (88–100); BP: 62 (51–92); GH: 82 (75–90); VIT: 75 (60–83); SF:7 5 (75–100); ER: 100 (33–100); MH: 76 (66–86). PG after training (Median IQR 25th–75th percentiles) PF: 95 (78–95); RP: 100 (100–100); BP:82 (62–100); GH:82 (77–92); VIT: 85 (75–90); SF: 100 (87–100); ER: 100 (100–100); MH: 84 (78–96). | Three sessions/week, for one hour. 6 months. 78 sessions. | 96.1% of participants completed the follow-up. The Pilates was superior (p< 0.05) to WBV for muscle strength ofthe knee flexors at 60°/s (% Change: 16.71± 20.68 vs. 6.18± 19.42; Cohen’s d= 0.70) and superior (p< 0.05) to the control group in all muscular strength variables and in four SF-36 domains. |

| Oliveira et al. (2019) | SF -12 | PG before training: SF-12 - PC: 29.7± 8.4; SF-12 MC: 41.7± 7.3. PG after training: SF-12 - PC: 39.9± 9.0; SF-12 MC: 47.7± 9.7. | Two sessions/week, for 50 min. 12-weeks. | In this study, patients undertaking the Pilates method for 12 weeks had less pain, better function and QoL, and increased range of joint movement. |

| Özyemişci Taşkiran et al. (2014) | Turkish version of NHP. | Significant differences were found in the total NHP score, mean difference (before and immediately after the intervention) in the PG (0.95± 14.10; p= 0.007). | Three sessions/week for 50 minutes. Eight weeks. | Sleep scores (-2.22± 21.57; -6.67± 18.15; 10.00± 22.04 for Pilates, yoga and control groups, respectively; p= 0.026) and emotional reaction subdomains (-2.08± 23.19; -6.94± 15.59; 6.82± 14.29 for Pilates, yoga and control groups, respectively; p= 0.037) on the NHP decreased immediately after exercise in both groups, and post hoc analyses revealed that the decrease in sleep and emotional reaction scores reached significance only in the yoga group. |

| Rahimimoghadam et al. (2018) | KDQOL-SF | PG before training: PHCS: 22.1± 12.1; MHCS: 15.3± 13.2; KDCS: 28.5± 12.0; Total QoL: 21.9± 12.4; PG after training: PHCS: 53.8± 11.2; MHCS: 51.5± 14.6; KDCS: 50.6± 13.3; Total QoL: 52± 13.07. | Three sessions/week, for one hour. 12 weeks. | Comparison of the mean differences at the beginning and two months after the study in the two groups showed that the scores related to QOL dimensions in the Pilates group were more significant than in the control group (p≤ 0.05). |

| Rodrigues et al. (2010) | WHOQOL-OLD, | PG before training: QVG: 88.23± 6.19; PG after training: QVG: 89.35± 9.38. | Two sessions/week. Eight weeks | The Pilates method can offer a significant improvement in personal autonomy, staticBalance, and QoL. |

| Saltan and Ankarali (2021) | NHP | PG before training: 114.21± 74.78. PG after training: 72.55± 65.01 (p= 0.000); PG difference After training after Tukey’s post hoc test: -41.65± 50.06. | Three sessions/weeks. 12 weeks. | A positive effect was found on the pain, physiological status, and QoL in the PG. |

| Surbala Devi et al. (2013) | SS-QOL | PG before training: 312.25± 11.8. PG after training: 326.42± 11.5. | Three sessions/week, for 45 minutes per session. Eight weeks. | FRT (p= 0.000 in both groups), TUG (p= 0.000: Pilates and p= 0.001: Control), DGI (p= 0.000 in both groups) showed highly significant differences before and after eight weeks of intervention. |

| Surbala Devi et al. (2014) | RAND-36 | PG before training: 63.9± 3.0. PG after training: 82.6± 2.1. | Three sessions/week, for 45 minutes 6 weeks. | The PG was shown to have more significant improvements in QoL compared to CBT and CG. |

| Vancini et al. (2017) | The SF-36, translated andvalidated for Brazilian Portuguese. | PG before training: FC: 70.2± 17.2; LBPA: 65.5± 33.0; Pain: 64.7± 20.4; GH:75.3± 14.0; VIT: 47.4± 22.7; SF: 57.7± 28.9; LBEP:46.0± 40.0; MH: 60.0± 19.3. PG after training: FC:75.5± 17.0; LBPA: 76.2± 34.9; Pain: 75.0± 23.7; GH: 80.5± 9.9; VIT:65.9± 18.7; SF: 81.5± 24.9; LBEP: 77.8± 33.9; MH: 74.1± 22.4. | Three sessions/week for 60 minutes. Eight weeks. | The HR during the physical training sessions was significantly lower in the Pilates group (P) when compared to the walking group (W) (p< 0.0001). |

| Yentür et al. (2021) | Turkish version ofthe RAQoL |

PG before training: 6.20± 4.58; Aerobic group before training: 6.80± 4.80; Combined before training: 8.70± 5.20. PG after training: 1.50± 0.30; Aerobic group before training: 1.60± 0.45; Combined group after training: 2.80± 0.71. |

Three sessions/week, for about 45 min per session. | The present study showed significant improvements for the Pilates group in fatigue, depression, aerobic capacity, QoL (p< 0.05). |

| Yucel and Omer (2018) | SF-36 | PG before training: Pain (3.00± 4.00), Fatigue (5.00± 2.00); SF-36 PH (40.0± 3.0); SF-36 MH: (29.00± 5.00). PG after training: Pain (2.00± 2.0), fatigue (4.00± 1.00); SF-36 PH: (41.00± 4.00); SF-36 MH: (35.00± 3.00). | Three sessions/week, for 45 minutes. 12 weeks. | Pilates affect the parameters of QoL in women with type 2 diabetes, and they might be recommended as a part of theirtreatment program. |

| Yun et al. (2017) | SS-QOL | PG before training: Physical:3.08± 0.54; Social: 2.70± 0.66; Psychological: 2.85± 0.42; Total QoL: 2.88± 0.47. PG after training: Physical:3.32± 0.64; Social:3.08± 0.66; Psychological: 3.23± 0.64; Total QoL: 3.23± 0.56. | Two sessions/week, for 1 hour .12 weeks. | Pilates sessions improved patients in the experimental group in all domains of QOL. |

AS: Arm subscale; ASQOL: ankylosing spondylitis quality of life questionnaire; BASFI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BBS: Berg Balance Score; BCS: Breast cancer subscale; BP: Bodily pain; BSA: Body self-analysis; CBT: Conventional Balance Training; CG: Control Group ; CKDS: Chronic Kidney Diseases Summar; DGI - Dynamic gait index; DS: Diet Satisfaction; DA: Daily Activities; EA: Emotional Aspects; ECS: Emotional component summary; EMH: Emotional/ Mental Health; EORTC QLQ-C30 (EORTC QLQ BR23): The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Questionnaire; ER: Emotional Role; ERF: emotional role functioning; ERL: emotional role limitation; ESSA: Emotional situation self-analysis; EWB: Emotional well-being ; FACT: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; FACT-B: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast; FC: Functional Capacity ; FG: Factor-G (PWB + SFWB + EWB + FWB); FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; FRT - Functional reach test; FW: Financial Worries; FWB: Functional well-being; ; GH: General Health; GHP: General Health Perception; GHS: general health state; HC: Health change; HSA: Health self-analysis; HT: health changing over time or the reported health transition; HW: House Work; KDQOL-SF: The Quality of Life Short Form; LBEP: imitations because emotional problems; LBOEM: limitations because of emotional problems; LBPA: limitations because of physical aspects; MCS: Mental component summary; MF: Mental Functions; MH: Mental Health; MHCS: Mental Health Components Summary ; MHD: Mental Health Domain; MP: Mat Pilates; MusiQol: The Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life Questionnaire; NHP: Nottingham health profile; OMSA: Overall motility self-analysis; PCS: Physical component summary; PE: Physical Endurance; PedsQL 4.0: .Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0; PF: Physical functioning; PG: Pilates Group; PH: Physical Health; PHA: Physical Aspects; PHCS: Physical Health Components Summary; PI: Pain intensity; PPFA: past-present-future activities; PR: Physical Role; PSCS: psychosocial; PRF: physical role functioning ; PWB: Physical well-being; QoL: Quality of Life; QOLID: Questionnaire for Quality of Life; QVG: quality of life index; RAND-36: The RAND 36-Item Health Survey ; RAQoL: Rheumatoid Arthritis Quality of Life Questionnaire; RLE: Role limitation due to emotional problems ; RLP: Role limitation due to physical health; RM: Roland Morris ; RP: Role-physical ; RS: Role Social; RT: Resistance Training; SA: Social Aspects; SAS: Social Aspects; SB: Symptom irritability; SF: Sensory functioning ; SF-12-MC: 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey—Mental Component; SF-12-PC: 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey—Physical Component ; SF- 36: Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey; SFWB: Social or family well-being; SI: Self Image; SLSA: Stress levels self-analysis; SP: Social Participation; SRF: social role functioning; SRS-22r: Scoliosis Research Society Questionnaire; SS- QOL: Stroke specific quality of life; TOIS: Trial Outcome Index score (PWB + FWB + BCS); TS: Total score (Factor-G + BCS); TUG - Timed up and go test; VIT: Vitality; WHOQOL: The World Health Organization quality of Life questionnaire; WHOQOL-OLD: The World Health Organization quality of Life questionnaire – Old.

Table 3 Outcomes of the included studies.

| Author/Year | Statistical tests used | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main results | Is pilates practice related to better Qol? | ||

| Altan et al. (2009) | Shapiro–Wilk test. Wilcoxon test. T-test and Mann–Whitney U test. χ2 test and Fischer’s exact test. | In PG, BASFI showed significant improvement at week 12 (P= 0.031) and week 24 (P= 0.007) (post-treatment), BASMI, BASDAI, and chest expansion showed significant improvement (P= 0.005, P= 0.036, P= 0.002), while there was no significant change for ASQoL at week 12. According to the results, Pilates is an effective and safe method to improve physical capacity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. | YES. ASQoL. |

| Angin et al. (2015) | Mann-Whitney-U test | BMD values increased in the Pilates group (p< 0.05), while BMD decreased in the control group (p< 0.05). Physical performance test results showed significant increases in the Pilates group (p< 0.05), whereas there were no changes in the control group (p> 0.05). The pain intensity level in the Pilates group was significantly decreased after the exercise (p< 0.05), while it was unchanged in the control group. There were significant increases in all parameters of QOL in the Pilates group. |

YES. All parameters of QoL in the Pilates group. |

| Borges et al. (2014) | T-test. | The results provide evidence of positive effects on pain intensity and almost all domains of QoL when patients followed the Pilates exercise program described. | YES. PF; PRF; BP; VIT; GH; SRF; MH. |

| Campos De Oliveira et al. (2015) | Mean and standard deviation. Mann-Whitney U test. Shapiro-Wilk test. Two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s post hoc test. Kruskal-Wallis test and the Student-Newman-Keuls | EG showed significant improvements in all subscales after the intervention. However, CG showed improvement only in social role functioning. Pilates exercises improved isokinetic torque of the knee extensors and flexors, postural balance, and HRQoL. | YES. PF; PRF; Pain; GHS; VIT; SRF; ERF; MH. |

| Eyigor et al. (2010) | Descriptive statistics. The Mann-Whitney U Test. Fisher’s Exact or χ2. Wilcoxon test. | After the exercise program, improvements were seen in Group 1 in the 6-minute walk test, BDI, EORTC QLQ-C30 functional, and EORTC QLQC30 BR23 functional scores (P< 0.05). In contrast, no improvement was observed in Group 2 after exercise. Pilates exercises are effective and safe for female breast cancer patients. | YES: EORTC QLQ-C30-Functional; EORTC QLQ-C30-Symptom; EORTC QLQ-C30-Global; EORTC QLQ-C30 BR 23 functional; EORTC QLQ-C30 BR 23 Symptom. |

| Gandolfi et al. (2012) | Mean and standard deviation calculations for quantitative variables and frequency and percentages for qualitative variables. Shapiro–Wilk test. T-Student test. χ2 test. ANOVA time-repeated measurements. Tukey test.. | The PG presented improvement in the QoL evaluation scores: PF, and PCS; PF; PR; ER, VIT, PCS and ECS, but without changes in bone remodelling. | YES. PF; PCS; PR; ER; VIT; ECS. |

| García-Soidán et al. (2014) | Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Fisher’s distribution. | NR | The results showed that the Pilates Method generated important changes in middle-aged individuals, bringing benefits to the domains of QoL |

| Karaman et al. (2017) | Descriptive statistics as a mean± standard deviation; Shapiro-Wilk test; t-test | We found a significant difference in balance and QoL with a 6-week postoperative Pilates-based exercise program combined with standard exercise compared to standard exercise alone following TKA surgery. | YES. GH; SFD, and mental component. |

| Kheirkhah et al. (2016) | χ2 test, independent t-test, and paired t-test. | According to the results of the study, Pilates exercise can be considered an effective alternative to improve the quality of life, health, socioeconomic, psycho-spiritual, and family functioning of hemodialysis patients. In the control group, no difference was observed between the QoL scores at the beginning and at the end of the study. | YES. HEALTH AND SOCIOECONOMIC. PSYCHO-SPIRITUAL. FAMILY. TOTAL QoL. |

| Kofotolis et al. (2016) | Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; MANOVA; Mauchly’s test; F test. | An 8-week Pilates program improved HRQoL and reduced functional disability more than a trunk strengthening exercise program or controls among women with chronic low back pain. | YES. Autonomy and perception. |

| Vécseyné Kovách et al. (2013) | T-test; ANOVA. | WHOQOL showed improvement in perception and autonomy in the Pilates group. | YES. Perception and autonomy. |

| Küçük et al. (2016) | Descriptive statistics. Wilcoxon test. Mann-Whitney U test. | The present study results showed that individuals in the Pilates group had significantly positive effects on QoL and cognitive functions compared to the control group. Showing that the use of Pilates for patients with multiple sclerosis can be beneficial. | YES. Total QoL. |

| Lim and Park (2019) | Analysis of variance (ANOVA). Scheffé test. Adjusted for: Health condition, role limitation due to physical health, role limitation due to emotional problems and energy. | When comparing pre-and post-exercise, we found a statistically significant difference between the three groups in FMS (F [2.89]= 15.56, P< 0.001), and there was an improvement in the SF-36 domains in the Pilates Group (F [2.89]= 52.36, P< 0.001). The Pilates group presented better results in functional movement and individual health levels when compared to the Yoga and control groups. | YES. PF; RLP; RLE; ENERGY; EWB; SF; PAIN; GH; HC; SF-36 Total. |

| Liposcki et al. (2019) | Attendance and percentage for qualitative variables, and means, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values for quantitative variables. Shapiro-Wilk test. The Student’s T-test, Mann-Whitney U test. | After the exercise program, 89% of the women in the PG had an excellent QoL, while in the CG, 46% of the women in the CG considered their QoL to be bad or poor. The results of this study showed that Pilates could improve the QoL of sedentary elderly women | YES. General QoL. FC; PHA; PAIN; GH; VIT; SAS; EA; MH. |

| Medeiros et al. (2020) | Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Levene test. ANOVA mixed model. Bonferroni post-hoc test. | There was an improvement in both groups concerning pain and function (p< 0.05). The QoL domains and the FABQ questionnaire showed improvements in PG. PSQI and PRCTS showed improvements only in the aquatic aerobic exercise group (p< 0.05). Significant improvements were observed in the two groups in relation to the disease symptoms, and no differences were observed between mat Pilates and aquatic aerobic exercise in any of the measured variables. | YES. RS; GH; VIT; FC; RP; EA; Pain; MH. |

| Natour et al. (2015) | Student’s t-test (parametric variables) and Mann-Whitney (non-parametric variables); ANOVA; comparisons test (Post Hoc). | Statistical differences favoring the Pilates Group were found with regard to pain (P< 0.001), function (P< 0.001) and the QoL domains of FC (P< 0.046), pain (P< 0.010) and VIT (P< 0.029). Statistical differences were also found between groups regarding the use of pain medication at T45, T90, and T180 (P< 0.010), with the EG taking fewer NSAIDs than the CG. | YES. FC, PAIN, and VIT. |

| Odynets et al. (2019) | Shapiro-Wilk test; t-test. | The Pilates group showed better functional (20.65± 0.61) when compared to yoga and water activities. | YES. PWB; SFWB; EWB; FWB |

| Oliveira et al. (2019) | Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test was performed for quantitative variables; Shapiro–Wilk normality test for quantitative variables; Student’s t-test for paired samples. | The Pilates group presented lower VAS (P< 0.001), lower HAQscores (P< 0.001), and higher QoL scores (P< 0.001) compared with the control group. We found statistically significant results for the Pilates group in the range of movement for the shoulder, knee, ankle, and lumbar spine (P< 0.001). In the intragroup analysis, there was a significant improvement in all outcomes evaluated. | YES. QoL Scores. |

| Oliveira et al. (2018) | Initially, intention-to-treat analysis (ITT). Mean and standard deviation (SD), respective interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles). Shapiro-Wilk test. The Student t-test. Levene test. One-way ANOVA. Kruskal-Wallis test. Covariance analysis (ANCOVA). As a post hoc, the Bonferroni test. | Pilates is an alternative intervention superior to WBV when the goal is linked to the strength of the knee flexor muscles. | YES. RP; BP; SF; ER. |

| Rahimimoghadam et al. (2018) | Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Mann-Whitney U, and Wilcoxon tests | The Pilates exercises effectively improved the participants’ QOL and its dimensions. Due to the cost-effectiveness and safety of this intervention, we propose the inclusion of this exercise in CKD patients’ treatment protocols | YES. PCS, MCS, and KDCS |

| Rodrigues et al. (2010) | Shapiro Wilk test; t-test. | Based on this study, it is possible to conclude that the practice of the Pilates method can improve the functional autonomy and static balance of elderly individuals. However, concerning QoL, we suggest that further studies be carried out using a more representative sample and a more extended period of intervention to more precisely evaluate the results of the method with respect to this variable. | YES. Sensorial abilities; social participation; privacy. |

| Saltan and Ankarali (2021) | Mean± standard deviation, and as frequencies (counts and percentages). Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. One-way analysis of variance. Post hoc Tukey test. Pearson’s χ2 test. Paired-samples t-test. | After the intervention, there was a significant reduction in the training groups for VAS, NHP, WHr, and BDI values (P< 0.05). Also, there were no significant decreases in the control group’s VAS, NHP, WHr, and BDI values. When the three groups of BMI, VAS, ODI, NHP, and BDI values changed after training were compared, they were found significantly different. A post hoc Tukey test showed that the control group was significantly different from the other two groups (P < 0.05) | YES. NHP. |

| Surbala Devi et al. (2013) | Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Mean and standard deviation; student t-test; | There was significant improvement (p< 0.05) in functional balance and QoL of sub-acute Stroke subjects in the Pilates group compared to the Control group after eight weeks of training. | YES. General QoL. |

| Surbala Devi et al. (2014) | Mean and standard deviation. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Repeated measure ANOVA. Student’s t-test. | The 6-week PG and CBT program resulted in significant improvements in functional balance (FRT, TUG & DGI: P= 0.000) and QOL (RAND-36: P= 0.000). Both PG and CBT can improve functional balance and decrease the propensity for falls in the elderly, thus improving QoL. However, the PG was considered superior in elderly outpatients. | YES. RAND-36 |

| Özyemişci Taşkiran et al. (2014) | Shapiro-Wilk test. ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis. Post hoc analyses (Tukey or Mann Whitney U test, respectively), Wilcoxon or paired-T tests. | No improvement was seen in balance scores immediately after the intervention in either group. Improvements were seen in chair stand and 8-foot up, and test scores did not reach statistical significance after the interventions (p= 0.074 and p= 0.083, respectively). These effects also did not persist after six months. Reduction in pain, depression or disability and improvements in balance or body composition were not observed. | NO. |

| Vancini et al. (2017) | Levene’s test, mean± standard; Unilateral analysis of variance; Newman-Keuls post hoc test. | QoL, depression, and trait anxiety scores improved in the Pilates group. However, there was no better result in anxiety-state scores in this group. | YES. VIT; SFD; LBOEM; MH. |

| Yentür et al. (2021) | Shapiro-Wilk test, histograms, probability plots. One-way ANOVA; Kruskal-Wallis test; paired sample t-test; Wilcoxon signed ranks test. | Pilates Method can lead to beneficial effects similar to those of aerobic exercise in patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. | YES. GENERAL QUALITY OF LIFE. |

| Yucel and Omer (2018) | Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. t-test. | Pilates affect the parameters of QoL in women with type 2 diabetes, and they might be recommended as a part of theirtreatment program. | YES. Pain, fatigue, MH; anxiety, depression, FBG; and GHV. |

| Yun et al. (2017) | Shapiro-Wilk test. T-test. | The practice of Pilates by stroke patients positively affected the QoL of this population. It was found through the results a statistically significant improvement in the physical, social and psychological areas and total QoL. | YES. Physical, social, psychological, and total QoL |

10mW:10-meter walk ; ASQoL: ankylosing spondylitis quality of life questionnaire ; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index ; BASFI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index ; BASMI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index ; BCS: Breast cancer subscale; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory ; BMI: Body Mass Index; BP: Bodily Pain ; CG: Control Group ; DS: Diet Satisfaction ; EA: Emotional Aspects; ECS: Emotional component summary; EMH: Emotional/Mental Health; EORTC QLQ-C30 (EORTC QLQ BR23): The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Questionnaire ; ER: Emotional Role; ERF: emotional role functioning ; EWB: Emotional well-being; FBG: fasting blood glucose; FC: Functional Capacity; FG: Factor-G (PWB + SFWB + EWB + FWB); FMS: Functional Movement Screen ; FW: Financial Worries; FWB: Functional well-being; GE: Experimental Group; GH: General Health; GHS: general health state; GHV: glycosylated hemoglobin values; GPA: General physical activity; HC: Health change; HT: Health Changes over time or the reported health transition; KDCS: Kidney Diseases Components; LBOEM: limitations because of emotional problems; MCS: Mental Component Summary; MH: Mental Health; NHP: Nottingham health profile; NR: Not Related; ODI: Oswestry Disability Index; PCS: Physical Health Components; PE: Physical Endurance; PF: Physical Function; PFC: physical functional capacity; PG: Pilates Group; PH: Physical Health; PHA: Physical Aspects; PPFA: past-present-future activities; PRF: physical role functioning; PR: Physical Role; PTTs: Putting on and taking off a t-shirt; PWB: Physical well-being; QoL: Quality of Life; RE: Role Emotional; RLE: Role limitation due to emotional problems; RLP: Role limitation due to physical health; RP: Role Physical; RSP: Rising from a sitting position; RVDP: Rising from a ventral decubitus position; SA: Social Apects; SB: Symptom irritability; SF: Social Function; SF – 36: Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey; SFD: Social Functioning Domain; SFWB: Social or family well-being; SRF: social role functioning; TKA: Total knee arthroplasty; TOIS: Trial Outcome Index score (PWB + FWB + BCS); TS: Total score (Factor-G + BCS); VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; VIT: Vitality; WHr: Waist/hip ratio.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Two leading investigators independently (FSAS e LCSA) performed the risk of bias assessment. There were no differences between the two evaluators. Of the 30 articles evaluated, 10.3% (n= 3) had a low risk of bias (Appendix 3), with only “yes” answers for all parameters evaluated (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to identify, through a systematic literature review, the influence of PM on the QoL of its practitioners. From the evaluation of the selected articles, it became evident that the practice of PM improved QoL in individuals of both sexes with different clinical conditions and established diagnoses.

Pilates Method is already recognized for its effectiveness in physical health. Thus, evaluating its importance in the QoL of its practitioners widens the horizon of application of the technique regarding clinical indications for which Pilates can be recommended. Among the selected studies, it was possible to verify scientific productions on the subject in different parts of the world, with a predominance of publications by Brazilian and Turkish authors. Despite numerous PM practitioners in Brazil, publications on the subject are still considered incipient, with great potential for development and new records on the benefits of the technique (Macedo, Haas, & Goellner, 2015).

General characteristics of the sample and overview of the methodological aspects of the selected studies

The 30 studies selected for this systematic review demonstrated the practice of PM in individuals of both sexes, different age groups, distributed in different countries, and with different clinical conditions. It is noteworthy that it was not possible to stratify the selective age group categories since most of the selected articles worked with a wide range of ages, from the age of eighteen (García-Soidán, Arufe Giraldez, Cachón Zagalaz, & Lara-Sánchez, 2014).

The heterogeneity regarding the aetiology of the clinical conditions found in the researched studies, which involved people with neurological, endocrine, orthopedic, and oncological pathologies, may be related to PM being considered an eclectic activity with minimal contraindications related to its practice. Many individuals prevented from participating in other regular exercise programs due to certain physical and functional limitations find an open way to practice such a method that is gaining new adherents every passing day (Mallery et al., 2003; Amorim, Sousa, & Santos, 2011; Macedo et al., 2015).

Assessing QoL is always challenging for the researcher, as it comprises a series of factors with individual, subjective, and non-transferable characteristics. In this sense, the methodologies employed seek to incorporate, in the best possible way, instruments that can assess people’s opinions, thus improving health-related clinical practices. In this review, SF - 36 was the most used questionnaire (43.3%) among the selected studies, possibly due to its versatility, dynamism, validation, and ease of application, in addition to having been translated to over forty languages.

Aspects related to improving the QoL of PM practitioners among the selected studies

Among the studies selected in this review, the main aspects related to QoL improvement with the practice of PM were pain relief and mental health and functional capacity improvement.

To recall the concepts, functional capacity (FC) can be defined as the ability to perform basic activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), linked to the individual’s quality of life once it determines their independence, self-care, and their social participation, and is considered an essential marker of the individual’s clinical situation (Yentür, Ataş, Öztürk, & Oskay, 2021).

On the other hand, mental health was defined by the WHO as the feeling of well-being in which the individual develops their personal skills, manages to deal with the stress of life, works productively, and can contribute to their community (WHO, 1997).

According to Lopes et al. (2019), the practice of PM because it involves exercises that combine physical well-being with mental health through stretching and muscle strengthening, improves body functionality, and becomes an essential tool for reducing drug use and other analgesic therapies, contributing to mental health improvement.

The PM provides its practitioners with global benefits, evidencing increased flexibility, range of motion, body awareness, decreased pain, improved posture, and aid in treating depression, anxiety, and stress. To achieve the intended objectives, it is necessary to correctly apply the technique keeping its main pillars intact: fluidity, concentration, coordination, centralization, breathing, and precision during the execution of movements (Bezerra et al., 2020).

Improved QoL in PM practitioners compared to non-practitioners

Pilates Method has been classified as a safe and effective method to improve the functional capacity of people diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis. It is known that functional capacity gradually affects patients affected by ankylosing spondylitis since this pathology affects peripheral joints and the spine, causing pain and movement limitation. Altan, Korkmaz, Bingol, and Gunay (2009) conducted a study with 55 participants with ankylosing spondylitis, aged between 28 and 69 years, 30 males and 25 females. By dividing the participants into an experimental group (submitted to PM practice) and a control group (not submitted to PM practice), they found a significant improvement (P= 0.003) in the functional capacity of the individuals who practiced Pilates, with pain relief and greater independence to perform ADL’s.

Corroborating Altan et al. (2009), Natour et al. (2015), when carrying out a randomized clinical trial with sixty patients of both sexes, aged between 18 and 50 years, with a diagnosis of non-specific chronic low back pain for at least twelve months, found a significant improvement in pain levels (p< 0.01) in the experimental group (performing PM) compared to the control group (no intervention). The groups were formed by thirty participants each; in both, the volunteers were making use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. After 180 days, the study concluded that PM is an important ally in chronic low back pain of non-specific origin, contributing to reducing medication use in patients. Improvement was assessed using the visual analogue pain scale (VAS). Pilates Method utilizes exercises aiming at strengthening the spinal stabilizing muscles, a region called by Joseph Pilates as the centre of force or powerhouse, promoting pain relief at rest and during gait.

Pilates Method is effective for several factors related to mobility and flexibility of the spine, correction of postural alignment, improvement of balance, reduction of pain in chronic low back pain, and improvement in health in general (Macedo et al., 2015).

It is noteworthy that regular PM practice potentializes previous directions given by doctors according to the patients’ needs, limited by their necessities, with a special focus on aerobic exercises, nutritional assessment, and lung expansion activities (Ince, Sarpel, Durgun, & Erdogan, 2016).

Joseph Pilates, the creator of the method, advocated that the body should always be worked in its entirety, using exercises that promote stretching and strengthening of the musculature, centring the production of force in the abdominal region, which he called the centre of force. This factor contributes to a better functional autonomy of its practitioners, regardless of age or clinical condition (Yentür et al.,, 2021).

The recovery of bone mineral density in patients diagnosed with osteoporosis is of paramount importance, given that this pathology is associated with numerous cases of hip fractures, considered a public health problem and an economic impact associated with hospitalizations and deaths. In another study of this review, following a group of 42 postmenopausal women aged between 40 and 69 years diagnosed with osteoporosis, Angin, Erden, and Can (2015) divided them into two groups, one with the intervention of PM and a control group, which did not perform any activity. As a result, after 24 weeks, they found a significant improvement in the functional capacity associated with recovery in bone mineral density in the hip region and pain reduction in the group that practised PM (p< 0, 05) with a weekly frequency of three days.

Pilates Method stimulates the body’s superficial and deep musculature through concentric, eccentric, and isometric exercises, thus transmitting a stimulus to the skeletal system, favouring the remodelling of bone mineral tissue (Angin et al., 2015).

As for cerebrovascular accident (CVA), in studies carried out in India by Surbala Devi, Ratan, Gopal, and Satani (2013) and another one carried out in Korea by Yun, Park, and Lim (2017), with 20 and 40 patients of both genders, respectively, the importance of PM in the quality of life of these individuals was demonstrated. The first, consisting of an 8-week-long intervention with three weekly sessions, showed a significant improvement in functional balance, leading to an improvement in general health compared to the control group (without activities) in the domains of the SS-QOL questionnaire. The second mentioned study adopted a 12-week-long intervention schedule with two weekly sessions and showed significant improvements in the physiological, psychosocial, physical, and quality of life parameters of the previously mentioned questionnaire.

Exercises performed with PM can help individuals with CVA to improve tone and muscle deficits, as well as postural control through individualized activities to meet each patient’s profile and their respective sequelae (Surbala Devi et al., 2013).

Balance impairment is an important dysfunction factor to consider after having a stroke, as the risk of falls is high during the first year post-injury. In turn, falls can favour injuries of different severity, highlighting that femoral fracture is considered a public health problem (Yun et al., 2017).

Influence of PM on QoL compared to other activities

Aiming to evaluate PM and yoga’s influence on QoL and practitioners’ functionality, Lim and Park (2015) selected 90 individuals aged between 30 and 40 years in South Korea. The selection involved 30 individuals who were beginners in PM, 30 beginners in yoga, and another 30 individuals for the control group (who did not practice any physical activities). The sample consisted of individuals of both sexes. The result showed that, among the evaluated techniques, PM is more effective in improving general health, emotional well-being, and pain, showing a significant difference compared to yoga and the control group. In the authors’ view, the results may be related to the fact that PM integrates dynamic and varied body movements that require balance, stability, and mobility, allied to the methodology applied in its execution, while yoga focuses more on static exercises.

Pilates Method was also more effective than the vibrating platform in improving the QoL and torque curve of the knee flexor muscles in postmenopausal women. This evidence was obtained during a randomized controlled study carried out by Oliveira et al. (2019), in which 51 women participated, divided into a control group (n= 17), vibrating platform activity group n= 17, and PM group (n= 17). With these results, the authors believe combining the two methods can bring even better benefits than both used separately.

In a study carried out in Turkey with individuals of both sexes diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, Kuçuk, Kara, Poyraz, and İdiman (2016) showed, after 8 weeks of intervention with PM, significant improvements attributed to aspects related to ambulation, respiratory capacity, cognitive ability, and in all the domains attributed to QoL when compared to individuals belonging to the control group who performed conventional patterns of rehabilitation aimed at patients with multiple sclerosis.

Pilates Method practice in the selected studies varied between once, twice, and three times a week, with the last alternative being the most observed frequency. In addition, the average session duration was 50 minutes, and the number of sessions estimated as a research protocol in the studies ranged between eight and twelve weeks, predominantly.

Among the limitations found in this study, the lack of information in the results of some evaluated articles regarding the specificity of the domains that were successful with the practice of PM is noteworthy. However, despite these limiting factors, it is possible to consider that the compilation of information on aspects related to QoL in a systematic review study can be a first step for improving the methodological quality of studies on this topic and also another instrument for the professionals involved in the prescription of this exercise modality to base their professional practices.

CONCLUSION

From the articles observed in the present systematic review, it was possible to conclude that PM positively influences the QoL of practitioners in both sexes, different age groups, and with different clinical conditions. The main domains related to QoL improvement were functional capacity, pain relief, and mental health improvement.