Introduction

The territorial expansion of the Portuguese and Spanish monarchies gave rise to the first overseas cities in the primordial era of European globalization. Initially in North Atlantic Europe (the Azores and Madeira islands), then in Africa, and finally in the Americas and Asia, the Iberians had, by 1540, built or reconfigured cities in four continents. Over the subsequent centuries, cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Lima, and Goa underwent several social, urbanistic, and even political transformations, throughout which they continued to be a microcosm of the dynamics of the empires that controlled them, and therefore a rich and valuable source of information for historians.

These overseas cities attracted significant academic interest in the 1970s and 1980s. Seminal works by Anthony King, Catheryne Coquery-Vidrovitch, Woodraw Borah, and Robert Ross-to name just a few-laid theoretical foundations that still guide research into cities founded or developed outside of Europe during the early expansion of capitalism. These cities were at the heart of several imperial projects (Ross 1985; Coquery-Vidrovitch 1991) and had two essential characteristics: (1) power was almost entirely in the hands of a non-Indigenous minority; and (2) there were clear and marked ethnic, cultural, and, in some cases, religious differences between the colonizers and the local Indigenous populations (King 1985: 10).

The cities were hubs of colonial administration and major nerve-centers for communications and cross-cultural encounters. They were also places where inequalities between settlers and Indigenous populations were thrown into sharp relief. Naturally, the urban structure and functionalities varied significantly in line with each particular imperial project, as did the characteristics of the inhabitants. They had in common the fact that, unlike certain other imperial projects, colonial cities developed by the Iberians had important religious and cultural functions (King 1985: 26). However, certain differences emerged, so that Spanish colonial cities were clearly distinguishable from their Portuguese equivalent.

One characteristic of overseas Portuguese cities, both in Portuguese America and West Africa (and to a certain extent also in Asia) was the major presence and importance of non-European individuals. That contrasted with other imperial projects such as those of the British, French, and even the Spanish Monarchy, in which there was a clear pattern of keeping native populations separate from urbanization processes in colonial settler cities. Cities generally tended to be places where males outnumbered females, but there is as yet no clear and reliable interpreted data on the extent to which that was the case in the Portuguese Atlantic, and the possible reasons for this disparity. The study of Portuguese overseas cities also currently lacks reliable sources and methodologies that might lead to a quantitative perspective of the ethnic, religious, and legal status (slave, free, orphan, widow, etc.) of key social groups, their interactions (marriage, adoption, etc.), and the way they were categorized by the local authorities. This data and its interpretation will then enable us to better understand the dynamics of colonial populations in an urban context. The Portuguese Empire was essentially organized around port cities to a far greater extent than occurred in other imperial systems, such as that of the Hispanic Monarchy. These cities were established and developed very early on the colonization process. By the time Salvador was granted city status in 1549 (the first in Portuguese America) three port cities had already been founded in the European Atlantic, six in Africa, and a further six in in Asia. Study of these Portuguese urban areas is therefore highly relevant to the comprehension of modern and contemporary colonialism but has been somewhat overlooked in the main global syntheses.2 One of the main aspects of “colonial Portuguese cities” that merits further investigation is the demographic weight of certain segments (i.e., ethnic and religious groups as well as enslaved populations versus non-enslaved populations). This data can form the basis of comparison with other cities in the same geographical area and beyond and with cities in other empires. Specifically in the case of Latin America, it can provide a basis for a comparative analysis of, for example, the demographic weight of Indigenous populations in Spanish American urban centers compared to those of Portuguese America, differences in the statistical representativity of enslaved populations in the various cities, and the sex ratio and shortfall of females in Portuguese urban centers in Brazil and West Africa.

Demographic study of Portuguese Atlantic cities in the North Atlantic, Africa, and Brazil enables researchers to ascertain the terminology used by civil, ecclesiastical, and military authorities to classify and represent the local populations. Demographic data known as numeramentos (surveys) and subsequent recenseamentos (censuses) provide an insight into the prevalent attitudes towards social classification held by the central authorities in Portugal and the local colonial officers. The marked ethnic, linguistic, and religious heterogeneity and differences in legal status (i.e., between free citizens, slaves, and former slaves) are reflected in the categories used to classify individuals. The population records of cities usually contained broader ranges of classification than the records of non-urban areas. Conceptual study of the nomenclature used-“brancos” (white), “brancos da terra” (local white), “pardos” (mixed race), “pretos” (black), “índios” (Indian), etc.-allied with an analysis of the demographic representation of these groups enables the perception of various characteristics of modern colonialism and ways in which the Portuguese related to native populations.

This paper deals with the Atlantic cities (“cidades”) of the Portuguese Empire in the transition from the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries and is essentially a study of demographics. Portuguese colonial presence during the period in question continued to be largely concentrated in the coastal Atlantic cities. The strong economic growth of Brazil, together with the need to protect territory from incursion by rival European powers (especially Spain) led to a drive to populate the hinterland. The Portuguese Crown pursued a policy of establishing towns (“vilas”) in inland areas (the sertão), most notably in the Amazon region. Notwithstanding that, only three towns located away from the coast were granted city status in the eighteenth century-São Paulo (1711), Mariana (1745), and Oeiras (1761). Therefore, these were the only (non-port) cities to have been established in the whole of the Portuguese Empire since the fifteenth century.

Several academic articles have considered the demographic profile of various cities in Brazil and Africa. However, the present study provides a novel perspective. There is no lack of bibliography on overseas cities in the Portuguese Empire, particularly analyses of slavery, social groups, missionary activity, governance, and urban morphology. However, there are very few studies that relate colonial-era economic, social, and urban history to macro-level population dynamics and trends. That is true not only of the Portuguese port-cities but also of towns and cities that were under the dominion of other European empires, such as the British or the Dutch, and for which comprehensive comparative works on demography are a rarity.

In the 1970s, the groundbreaking work of authors such as Shelburne Cook, Woodrow Borah, Mary Karasch, John Russell-Wood, and Maria Luiza Marcílio paved the way for further research into urban populations in Latin America from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. Based on these investigations, academic researchers have highlighted the social diversity and multiplicity of the demographic trends that existed in these locations, even in the so-called “settler” towns and cities. It has already been established that colonial cities (not only those occupied by the Portuguese) tended to mirror the demographic patterns of their counterparts in the colonizing country. That was particularly the case for gender ratios (female predominance) and population age, which was higher in the cities than in rural areas (Klein 1996; Fauve-Chamoux 1998).

One distinguishing fact was that colonial cities, particularly those located in the tropics, had large contingents of slaves or former-slaves and other social groups that were categorized and distinguishable based on a range of characteristics, including, in particular, the color of their skin (Metcalf 2013). Researchers have also ascertained that indigent populations (beggars and other individuals of no fixed abode) were significantly higher in colonial cities than in the cities of the colonizing country. That would appear to be the case particularly in South America (Lara 2007).

Several Atlantic cities, especially the larger towns and cities in Brazil, have been the object of demographic analysis (Alden 1963; Marcílio 1984). Notable examples include research on the cities of São Paulo (Marcílio 1968), Rio de Janeiro (Bicalho 2003; Florentino 2002; Venancio 2013), Bahia (Salvador) (Mattoso 1992), Vila Rica (Costa 1981; Fonseca and Venancio 2008), and in Angola, the work of Curto and Gervais on Luanda (2001) and Mariana Candido on Benguela (2013). Several monographs provide important information, in varying degrees of detail, as to certain populational characteristics of Atlantic archipelago cities such as Ponta Delgada and Angra (Matos and Sousa 2015a), Funchal (Santos, Matos, and Sousa 2013), and São Tomé and Santo António (Neves 1989). As yet, however, there are few collaborative studies applying common analysis methodology to comparable data for similar timeframes.

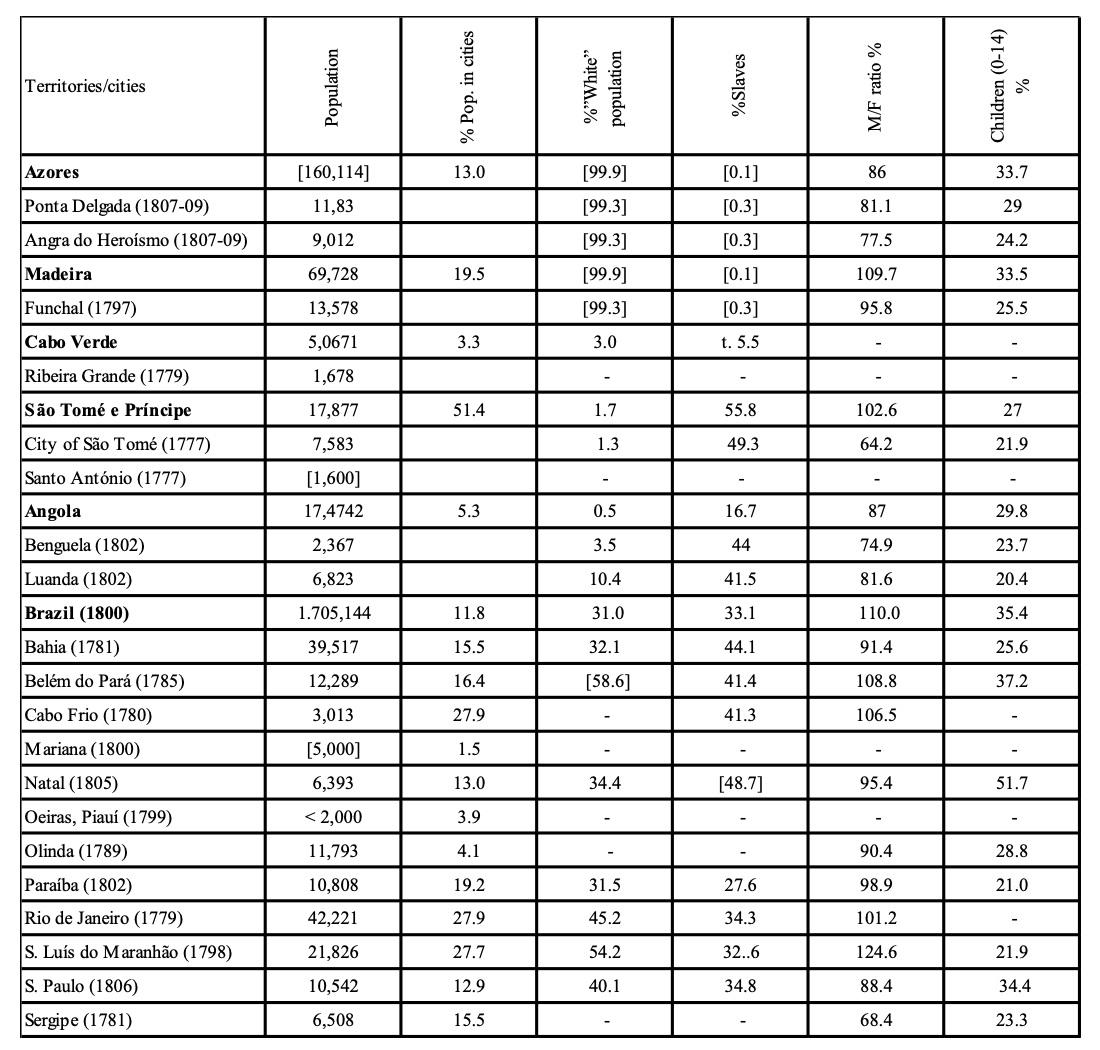

This study is the first comparative systematic analysis of demographic data on the twenty cities of the Portuguese Atlantic during the transition to the nineteenth century. Its first contribution is methodological, as the concept of city is far from being consensual, which leads us to question what defined city status in the eighteenth century. On the other hand, it is necessary to understand geographical and administrative limits of the urban areas in question, the formulation of a standardized procedure for identifying data on key categories (legal status [slave/free] marital status, filiation, and age group) obtained from diverse sources, and the decoding of the historical processes of the production and transmission of the data. This paper provides a reliable overview of urban demographics of the relevant areas to then carry out a comparative analysis with non-urban areas in the same region and other cities in the Portuguese Atlantic, as well as with other empires for which data is available. As such, this study will provide much needed evidence as to the specificity of colonial cities, although it does not dwell directly on the academic debate surrounding that. I argue that the 20 cities did not deviate significantly from the known demographic profile of other urban areas in the Portuguese colonies, or indeed in Portugal itself. In line with the general pattern for towns and cities, females outnumbered males, and the population was somewhat older than the surrounding non-urban areas, with comparatively few young people (0-14 years old). Perhaps unsurprisingly, some striking regional differences emerged, including the high percentage of the population of tropical cities that was enslaved (almost 50%) and the relatively diminutive presence of “white” population groups in certain cities, especially those of West Africa. The data systemized in this article enables confirmation of what were hitherto merely suppositions as to the demographics of certain areas.

This article is divided into two main sections. In the first, I examine the sources and the main methodological challenges, beginning with the definition or conceptualization of a city. In the second part, I begin by analyzing the data and calculating the number of inhabitants. In some cases those calculations correct earlier population estimates by other researchers in previous studies. I examine the ratio of the population of a given territory that lived in cities, as well as the social composition (including ethnicity) and legal status (i.e., slaves, freed slaves, or free citizens) of the city’s inhabitants, the sex ratio and the proportion of children (0-14 years old). Finally, I analyze the data for each city and compare it to the overall data for the respective territory to identify possible specificities of these cities.

Cities and Demography: Methodological Challenges

What is a city?

Defining a city is not always a straightforward task for historians, and there has been considerable academic debate as to the quantitative and qualitative criteria that should be applied. These criteria include the economic and administrative importance of the urban area in question (Lopes and Marques 2003: 23), which is consistent with Walter Christaller’s “central place theory” (1931), based on functionality. Other researchers favor purely objective data such as population size (Bairoch 1998: 218).

Given the vast array of urban areas in the Portuguese overseas territories and the quantitative and qualitative disparities between them, I focused the research on locations that were formally classified as cities (“cidades”) by the crown authorities. In other words, urban areas that were granted city status by means of a charter (carta foral) or royal letter (carta régia), as described by Serrão (1973). That then begs the question of how the Portuguese Crown exercised its discretion to confer city status.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, in most cases the crown’s decision was eminently political. Urban areas in Ancien Regime Portugal were either vilas (towns) or cidades (cities). Holding city status brought considerable economic and political benefits as well as social prestige, and local authorities (essentially members of the nobility and the Church) went to considerable lengths to obtain it. Requests for city status made by fidalgos (members of the nobility who were loyal to the Crown) or by ecclesiastical authorities of an urban area that was the site of an important religious edifice, were very likely to succeed. On the other hand, urban areas that lacked close ties to the King or particular religious significance were rarely granted a charter (Fonseca 2003: 44).

This system was perpetuated in the Portuguese overseas territories, with certain adapted criteria. The king was particularly inclined towards granting city status when the request came from urban areas that had a high density of European settlers (homens brancos) and even more so when the applicants were nobles (fidalgos) with close ties of kinship or friendship with the crown. If the fidalgos had somehow demonstrated their loyalty to the crown in the colonies, the request for city status had an even greater likelihood of success (Fonseca 2003: 48). When the governor of Mozambique requested a grant of city status in 1800, he cited as supporting reasons that many of the inhabitants were of European descent, “there are many sons and daughters of people who hail from Europe and its coastal areas, and they are so fair-skinned and blond as to resemble inhabitants of Northern European countries” (Wagner 2018: 308). The ecclesiastical authorities in Mozambique lent their voice to the governor’s application, asking the king to establish a bishopric in the region, which would only be possible following the granting of city status (Wagner 2018: 315). In 1822, the senate of the municipal council of Santo António (Príncipe Island in the Gulf of Guinea) asked the Portuguese authorities for capital city status, citing as grounds for the application the number of fair-skinned people on the island (94 in total), “almost all of whom are Europeans,” this number being far greater than that of neighboring São Tomé (a political rival) where the number of European descendants did not exceed 18.3

Given the geopolitical and economic reality of the colonies, other factors were often cited in support of an application for city status-favorable climate, an accessible port, commercial importance, and strategic value-and these aspects assumed far greater importance as the eighteenth century progressed into the nineteenth. The decision to grant city status was increasingly influenced by commercial and strategic factors. In terms of demographic criteria however, there were significant disparities. At the close of the eighteenth century, the population of the Portuguese cities in West Africa rarely exceeded 6,000, whereas the Brazilian vilas of Fortaleza and Vila Rica had 20,000 and 10,000 inhabitants respectively. Conversely, the city of Oeiras (Piauí) in Brazil had a population of just 2,000.

In this study, comparisons are drawn between the cities examined and the geopolitical and administrative space in which they were located (e.g., comparing sex ratio in Rio de Janeiro with Brazilian territory). It is not possible to make direct comparisons between cities located in different continents due to the vast demographic, administrative, political, economic, and social differences between them, and I have therefore not attempted to do so.

The Sources

The first large-scale headcounts of inhabitants in the Portuguese Empire were carried out in coastal urban centers in the seventeenth century. The findings were recorded in official population lists or parish records. These surveys were primarily designed to identify individuals for religious, tax, and military purposes. There was a marked increase in record keeping in several urban centers from the seventeenth century onwards, but territory-wide population censuses were rare in the overseas territories before the eighteenth century (Matos 2016). Consequently, it is only from the mid-eighteenth century onwards that it is possible to draw comparisons between the demographic characteristics of the cities.

In the 1760s, the Portuguese Crown, under the increasing influence of the Marquis of Pombal,4 tentatively began the systematic and periodic gathering of certain demographic information. The first large-scale population surveys were undertaken in Brazil and in the Azores (Matos and Sousa 2015b). This system was consolidated in 1776, when the crown issued orders to all overseas governors requiring them to draw up population tables of the areas under their jurisdiction (Alden 1963; Marcílio 2000; Matos 2016).5 These population tables are the principal empirical basis for this study. Most of them are stored at the Portuguese national archives of colonial history-the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino in Lisbon.6 In my view, they are the most reliable source of data currently available. I ruled out most other potential sources, particularly the demonstrably inaccurate recollections of explorers and other visitors to the territories.7

The population tables were drawn up in accordance with a predetermined model, issued by the Portuguese Crown for the purpose of identifying the age range of the inhabitants8 and for the registration of births and deaths (Alden 1963; Matos 2016). The royal orders, particularly those of 1776, rarely required the inhabitants to be classified by skin-color, religion, or legal status (i.e., free, slaves, or “Indians”). These classifications were nevertheless included by the local authorities, drawing on social distinctions that were commonly used in each territory. The terms usually applied were “branco” (white), “pardo” (mixed-race), “mulato” (also mixed-race),9 and “preto” (black), as well as “livres” (free) and “escravos” (slaves). The characteristics of these ‘population maps’ raise certain methodological issues such as: to what extent is it possible to standardize (i.e., render compatible) data from distinct geographical units? What is the best way of delimiting urban areas that are not clearly defined? How can we best comprehend the agents and institutions responsible for the collection of data and then draw meaningful comparisons between the urban spaces (cities) and the territorial or political units in which they were located? The following are the main challenges.

The Territorial Units

More specifically, the challenge lies in the way overseas territorial units were partitioned for the purpose of the census varied from region to region, usually in line with extent of Portuguese dominion over the area and the administrative capacity of the local authorities. In each of the Atlantic archipelagos, one general table (mapa) was drawn up and then subdivided into smaller units, referred to as freguesias or paróquias.10 In the kingdoms of Angola and Benguela, on the other hand, there were no general tables for the entire area. The regional military commanders (known as captains [capitães]) were responsible for drawing up a population table for each military zone (presídio) in collaboration with the ecclesiastical authorities and local potentates. Although the presídio table coincided (at least in theory) with the area of the respective ecclesiastical parish (paróquia), the geographical area was so wide that the parish authorities were unable to consistently collect accurate data (Matos and Jelmer 2013). Fortunately for demographic researchers, the military authorities also produced specific tables for the cities of Luanda and Benguela, which apparently coincided with the boundaries of the ecclesiastical parishes of São Paulo and São Filipe, respectively.

In Brazil, as in Angola, there was no overall population table for the entire territory. One table (mapa) was to be drawn up for each of administrative regions known as captaincies (capitanias). Within these areas, the ecclesiastical parishes (paróquias) were usually the smallest territorial unit for which data was gathered, but in many instances larger areas such (judicial districts) (comarcas) or military districts (companhias de ordenanças) prevailed as the basic unit for the purposes of population counts. The colonial authorities in the regions of Minas Gerais or São Paulo, used “municipalities” as the sole unit for some censuses. That gave rise to certain errors in the calculation of urban populations. The historians Cláudia Fonseca and Renato Venancio (2014: 165-166) have demonstrated that the figure of 20,000 inhabitants recorded for the town (vila) of Vila Rica (Minas Gerais) in 1797 was clearly overstated. In fact, this figure represented the population of the entire municipality, which was much larger than the town. A similar misconstrual seems to have occurred with the population of the city of São Paulo, which some historians claim had a population of 24,000 in the late eighteenth century, whereas in fact examination of the records indicates that in 1799 and 1803 a more accurate figure for the city, not the municipality, was around 10,000).11

The local authorities in the smaller territorial units would gather the local data and then submit it to higher authorities, who would then draw up the population list for the captaincy. The fact that the capitanias in Brazil did not use standard territorial units in drawing up their population tables complicates the task of both delimiting certain cities on a given date and comparing their demographic indicators with those of the surrounding areas in the captaincies. In some cases, I have been fortunate to have access to the “primary tables” (i.e., the original records), usually drawn up by priests (in the freguesias or paróquias) and submitted to diocesan authorities and which the colonial officers later used to compile the population tables for the captaincy as a whole. Some of these primary-level tables have been preserved at official state archives in Brazil or at the Overseas Historical Archives (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino) in Lisbon.12

The Data Producers

Notwithstanding all the inconsistencies between the territorial units used in the population tables in Angola and Brazil, there is no doubt as to the fact that the ecclesiastical parishes were the most common source of data, with the church being the institution that was best placed to gather information on the local population. The ecclesiastical nature of the information calls for some attention, in particular, to the possible underrepresentation on the registers of children under seven years old (seven being the so-called “age of discretion” for confession) and the omission of certain population groups that were not within the jurisdiction of the lay clergy, such as military personnel and members of religious orders. In some cities, such as Rio de Janeiro, Luanda, or Angra do Heroísmo, these population groups were recorded in separate ledgers.

Urban Perimeters

One of the main challenges in studying the demographics of the Portuguese Atlantic cities is defining the urban perimeters. The civil parishes (freguesias), particularly those that covered a large area, often extended beyond the limits of urban occupation and into the surrounding countryside, leading to significant distortions. Conversely, the largest urban areas, which registered the greatest rates of population growth, tended to extend over several freguesias. For example, the city of Angra de Heroísmo in the Azores included the freguesias of Sé, Conceição, Santa Luzia, and São Pedro, and in fact also extended to São Bento, which was usually classified in the sources as “extra-muros” (beyond the walls) of Angra. The city of São Paulo, Brazil, included the freguesias of Sé, Santana, Nossa Senhora do Ó, Penha de França, and Santo Amaro.

On the other hand, certain cities were smaller than the parishes of which they were a part. The city of São Luís do Maranhão in Brazil was part of the parish (paróquia) of Nossa Senhora da Vitória, which had a population of 22,000 in 1798. That figure probably included rural areas, but it is not possible to categorically confirm that at this stage. The city of Santo António (established in 1753) on Principe Island highlights the difficulty in identifying urban perimeters, in that the respective freguesia of Nossa Senhora da Conceição covered the entire island. The number of inhabitants in the freguesia was around 7,000, of which I estimate 1,600 lived in the city. This problem was not limited to the Portuguese Empire. Woodraw Borah documented identical difficulties in Spanish America, specifically late eighteenth-century Caracas, said at the time to have a population of 40,000. Subsequent research, however, demonstrated that the correct figure was 24,000 when the inhabitants of rural parishes in the surrounding areas were excluded (Borah 1980: 8).

The Relative Statistical Weight of Cities

The process of determining the relative statistical weight of the urban population is complicated by inaccuracies in the available figures for the overall population of the respective territory. This problem does not arise in the case of the Atlantic archipelagos, given their limited geographical scale, which meant that it was relatively easy for local administrators to identify and register the population. In Angola, on the other hand, and in almost all the Brazilian captaincies, important population groups (such as indigenous peoples in Brazil) were possibly underrepresented. Vast areas of the territory were beyond the control of the authorities, which meant that it was virtually impossible for them to accurately calculate the total numbers (Matos and Sousa 2015b; Matos and Jelmer 2013). Consequently, the relative statistical weight of the population of the cities in Brazil and Angola compared to the respective captaincies or presídios depends on the criteria used to quantify total populations, i.e., whether a conservative approach is taken, calculating population numbers on the basis of the number of people effectively under the control of the authorities, or alternatively, including in the calculations estimates for the so-called vassal populations (e.g., the sobas in Angola). In this article I adopt a conservative approach. That is, I calculate the total population of the territories based on data provided by Tarcísio Botelho (2015) and Paulo Teodoro de Matos (2016), drawing on official numbers recorded by the colonial authorities.

Census Periodicity and the Structure of the Information

Ideally, a comparison of the demographic structures of 20 cities would require that similarly structured censuses be performed in similar timeframes. However, in the Portuguese Empire, much of data was recorded at irregular intervals.13 The absence of systematic and convergent data means that it is not possible to define an exact cross-section. It was therefore necessary to extend the time period of the analysis to 1809 (see table 2).

In the case of Cape Verde and São Tomé and Principe islands, the urban perimeters of Ribeira Grande, Cidade de Santo António, and Cidade de São Tomé are only identifiable for the 1770s in that subsequent tables make no reference to freguesias: for Bahia, in Brazil, there are population surveys for the 1775-1785 period but very little information after that. For São Luis do Maranhão, also in Brazil, I was only able to obtain data on the number of inhabitants towards the end of the eighteenth century, because earlier tables did not itemize the figures into individual freguesias.

The differences in the structure of the census also makes it difficult to align various indicators (such as total population, number of slaves, and the number of children). We know the age structure of the city of São Tomé in 1777, but information as to its ethnic composition is only available for 1758 and 1771. Thus, I was able to calculate the total number of inhabitants in Luanda in 1802, but not the population under 14 years of age (table 2) which was only recorded in the 1781 census. All these limitations are obstacles to comparative demographic analysis.

Discussion of the Data

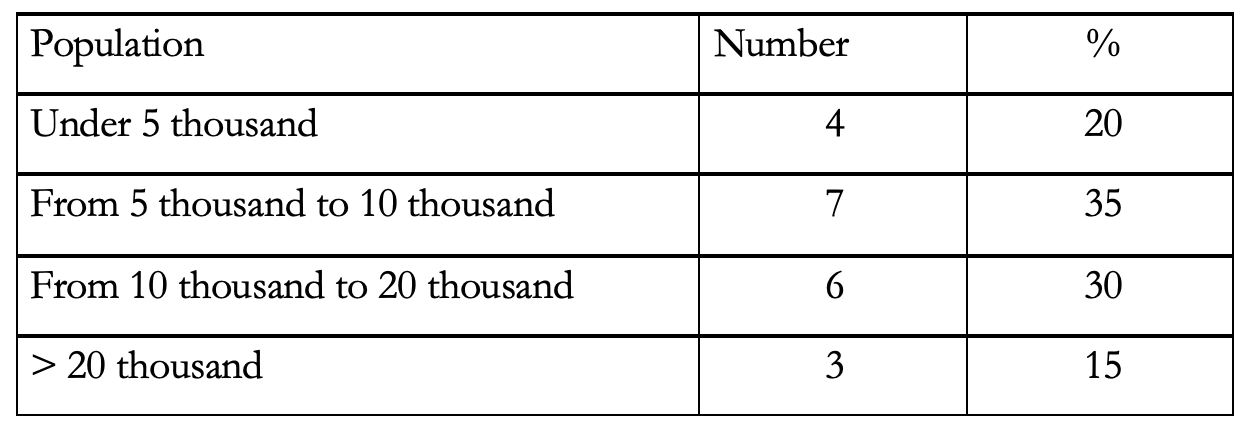

At the turn of the nineteenth century there were 20 officially designated cities in the Portuguese Atlantic dominions, three of which were in Europe, five in Africa, and 12 in Brazil. There was a very broad demographic variation between them: ranging from 1,600 inhabitants in Santo António (São Tomé and Principe) to 42,000 in Rio de Janeiro at the end of the 1770s. In Portugal itself, only two cities had over 20,000 people: Lisbon, which had 160,000 inhabitants in 1801 and Oporto, which had 44,000, in the same year (Sousa 1979: 181). Only five cities in mainland Portugal had between 10,000 and 20,000 people. The principal cities in the empire were Rio de Janeiro and Bahia (Salvador) with around 40,000 inhabitants each.

The demographic weight of the Atlantic cities was highly variable, even within the individual territories. Medium-sized cities (5-10 thousand) predominated. There were seven such cities: four in Brazil, two in Africa, and one in the Azores and Madeira archipelago. All the cities that had over 20,000 people were in Brazil (Rio de Janeiro, Bahia [Salvador] and São Luís do Maranhão), as were four of those with between 10,000 to 20,000 inhabitants. Brazil was also home to small cities of under 5,000 people, such as Oeiras or Cabo Frio, whereas two out of the three cities in the Azores and Madeira (Funchal and Ponta Delgada) had over 10,000 inhabitants each.

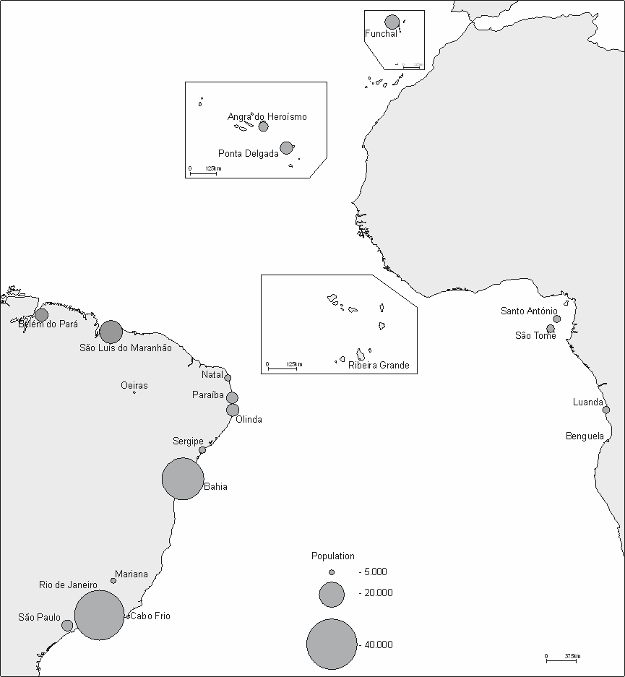

Map 1: Cities in the Portuguese Atlantic coasts, 1776-1809. (Paulo Teodoro de Matos. Authorized by author)

The Portuguese authorities systematically recorded the ethnic makeup of the overseas territories. The Royal Order of 1776 did not expressly state which social categories were to be included in the maps. But it is clear that the local authorities divided the population in categories according to their juridical status, which was based on race. Broadly speaking, people who were classified as white were invariably free (i.e., not slaves) and eligible for all manner of employment, including public office, civil, military, or religious functions. Mixed-race individuals (known as pardos or mulatos) held intermediate status if free (non-slaves), with some rights, but barred from high positions in the colonial administrative system. People who were classified as black (preto or negro) ranked just above slaves and had extremely limited access to the higher echelons in the administration. There were certainly exceptions to that general rule in Africa and in Brazil, where black individuals attained high social and economic status, particularly in areas in which there was a very small white European population.

The colonial authorities took particular care to register the white population. However, “white” was a somewhat hybrid category throughout the Empire. It was based not only on skin-color, but also on social and legal status as well as degree of cultural assimilation. Classification as white conferred clearly defined legal rights and prerogatives. In the African cities, the proportion of white Europeans in the population was negligible (between 1.5% and 10%). It was moderate in Brazil (between 31.5% in Paraíba and 59% in Belém), and very high in the archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira, where black and mixed-race (pardo) populations were rare.

The very large presence of slaves was a characteristic of all the Portuguese cities in West Africa and in Brazil. The lowest proportion (27.6%) was in Paraíba (Brazil), whereas in the cities of São Tomé, Benguela, Bahia, and Natal, there were almost as many slaves as there were free inhabitants. In some areas, the size of the slave population was inversely proportional to the white population. In West Africa, in particular, a very small number of white (and mixed-race pardo) individuals controlled enormous contingents of enslaved populations.

For the purposes of comparative demographic examination, it is helpful to divide the cities into groups, in accordance with their geographical location, approximate date of colonization, the political configurations of the territory in which they were located, and their predominant social composition. We therefore consider three groups: the Azores and Madeira, which were European territories where the so-called Atlantic colonization began; West Africa, including the archipelago of Cape Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe, and Angola on the continent; and, finally, Brazil, which was colonized later and home to 12 of the 20 cities considered in this study.

The Azores and Madeira, the sites of the first colonial cities, suffered from overcrowding from the seventeenth century onwards, leading to migration flows to several parts of the empire -in particular to Brazil-which indicates how quickly their population expanded (Russell-Wood 2011: 204). During the period covered by this study, the archipelagos were not colonies per se. Despite the presence on the islands of institutions that were typical of European colonization up until 1828,15 the inhabitants had the same legal status at those of the Kingdom of Portugal. We included these cities in this study because they were established during the early stages of the colonial process and because they, together with the Canary Islands, were the first overseas European urban centers.

In the context of Portugal and its Atlantic settlement the cities of Ponta Delgada and Funchal were demographically significant, occupying sixth and fourth place respectively in terms of population, which attests to their economic dynamism as important port centers. Despite the significant geographic discontinuity of the nine islands that make up the Azores, there was a considerable degree of urban concentration (13%). The degree of concentration was even higher in the case of Madeira (19%). By way of comparison, in 1801, only 11.6% of the population in continental Portugal lived in cities (Sousa 1979: 225).

These insular cities, particularly Funchal, are readily comparable to the Spanish Canary Islands, where, according to the Census of Floridablanca (1787), 16.6% of the population resided in the cities of La Laguna, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Santa Cruz de Palma, and Las Palmas in Gran Canaria (Jiménez de Gregorio 1968). However, none of these Spanish cities had a population of over 10,000. Funchal, in Madeira, had 13,500 inhabitants and was one of the most important urban centers of Portugal and its entire Atlantic area. In the Azores, Ponta Delgada was already a large city by Portuguese standards, and its demographic weight already exceeded that of the capital of Azores, Angra do Heroísmo.

The ethnic configuration of these insular cities was markedly homogenous, and non-white populations only had a residual statistical weight, in marked contrast to the typical colonial cities. As was the case in the African territories and Brazil, the population censuses of the Azores continued to use “black” (preto) and “pardo” (mixed-race) as classification criteria. Nevertheless, the tables for the Azores did not contain a category for “slaves,” which confirms the reduced demographic significance of slavery at the end of the eighteenth century (Caldeira 2017:127-134). In 1801, there were 461 individuals classified as black or mixed-race in the five largest islands of the Azores, corresponding to 0.4% of the total population.16 One notable aspect of the demographics of these insular cities was the higher numerical presence of females when compared to the archipelagos as a whole. There were also fewer children (aged <14) in the cities. The greater number of females is partially due to the greater concentration of domestic staff in urban areas. The cities, as per usual, also had a higher proportion of single people (including transient workers originally from other areas) and widowers, which probably contributed to a lower birth rate, hence the lower proportion of younger people, especially children under 14. In West Africa, the process of colonization of the archipelagos of Cape Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe began at the end of the fifteenth century. It was more protracted and irregular in the case of Cape Verde, where some islands were only populated from the eighteenth century onwards. Both Cape Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe had a strategic role in shipping routes, and São Tomé e Príncipe was particularly active as an entrepôt in the slave trade and later developed an important plantation economy. At the outset of the nineteenth century, the Kingdom of Angola was essentially a coastal dominion with around 15 military garrisons that sought to impose their dominion over local vassal chiefs, known as sobas. Wealth in the region was generated primarily from the slave trade.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, there were five cities in these dominions: Ribeira Grande in Cape Verde, the cities of São Tomé and Santo António in São Tomé e Príncipe, and Luanda and Benguela in Angola. The eighteenth-century history of the capital cities of the archipelagos was atypical. In Cape Verde, Ribeira Grande, the first Portuguese city in the tropics, sometimes referred to as “the first global city” due to its ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and commercial diversity, lost its status as capital of the archipelago in 1769 following successive epidemics.17 It nevertheless maintained its status as the only official city in Cape Verde, with a population of just 1700 inhabitants in 1779. In São Tomé and Principe, health and sanitation issues also led to the city of São Tomé losing its status as the capital to the city of Santo António on the island of Príncipe (which had a considerably smaller population) in 1753.

In the wider context of the Atlantic domains, the West African urban centers were relatively small-scale. The largest of them, São Tomé and Luanda, oscillated between 7,000 and 10,000 inhabitants, occupying the eleventh and twelfth positions in the ranking of the cities that are included in this study (table 2).18 By the standards of colonial Africa, however, these cities were by no means modest.19 According to Isabel Castro Henriques, Luanda was considered the third largest colonial city in sub-Saharan Africa, after Cape Town and Saint Louis in Senegal (Henriques 1997: 110-111). Oliveira Marques shares the same view, describing Luanda as the “major metropolis between Morocco and Cape Town” (Marques 1998: 144).

The population tables from the 1770s denote a major convergence in the form of classification of inhabitants of the African territories and the respective cities. They invariably distinguish between white, mixed-race pardos, 20 and black individuals, with the black and mixed-race population being subclassified as either “free” or “captive.” This classification according to skin color corresponded to certain rights and privileges (or lack thereof) and to legal status, in that pardos and black individuals could be classified as slaves.

One notable characteristic of the Portuguese cities in West Africa was the low percentage of white individuals in the population. The figure varied between 1.3% in São Tomé (1777) and 10.4% in Luanda (1802). Of a total of 900 white individuals in Angola in 1802, 710 were located in Luanda. This was a high number in colonial African terms (Matos and Jelmer 2013). It would seem that in early nineteenth century, Europeans were a rare sight outside Luanda, Benguela, or their hinterlands.

The low numbers of Europeans in Africa (and Asia) were constant up to the end of the nineteenth century and a permanent source of concern to the colonial authorities, who saw it as a threat to the implementation of their policies (Etemad 2007). As a general rule, local administrations, with the assistance of priests, kept detailed information on Europeans living in the area, and drew distinctions between those who were from the kingdom (do Reino-i.e., from Portugal), from abroad (de fora i.e., other Europeans), or of the land (da terra-i.e., European descendants born in the colony). In 1771, of the 76 white men and women living in the city of São Tomé, 27 were from the kingdom and 49 were natives (of the land). Interestingly, 34 out of the 49 natives were female, with only one female being from the kingdom. A document dated 1814 reflects administrative attention to detail, recording that on the island of São Tomé there were “21 pure whites (brancos puros), 35 “almost whites” (quase brancos), and 134 mixed-race individuals (pardos)” (Raimundo 1963: 43).

The white population did not thrive in these cities and that was for the same reasons that overall demographic growth was weak up until the mid-nineteenth century. Cape Verde, São Tomé e Príncipe, and Angola, like other areas of Africa during the modern and contemporary periods, suffered from recurrent epidemics, droughts, and famines that reduced their populations (Candido 2013; Curto 2001; Dias 1981; Neves 1989). In Cape Verde, the drought of 1773-75 led to a famine that killed almost a third of the inhabitants.21 Angola suffered from frequent droughts as a result of irregular rainfall patterns (Dias 1981) and successive health crises, with widespread death in Luanda and in Benguela from the late eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries. For example, in 1807, an outbreak of smallpox in Luanda took 1,967 lives in a year in which the city lost a quarter of its inhabitants.22

Despite medical and sanitary progress on the African continent during the second half of the nineteenth century, it was only at the beginning of the 1890s that the settlement of Europeans in Africa and Asia began to gather pace (Etemad 2007; Cogue 2020). Up until then, these continents were, as Philip Curtin (1990) put it, “the white man’s grave,” mainly due to the prevalence of malaria and yellow fever. In the smaller island territories, the high mortality rate of Europeans gave rise to other risks. In 1769, a contemporary noted that “the harsh climate of the land had decimated the white population to such an extent that there were no more than ten to twelve individuals left in São Tomé,” and there were widespread reports of mulatos murdering Europeans in order to take over their positions in the public administration (Neves 1989: 152). In 1784, the governor declared that the white population on the island of São Tomé was virtually extinct, because there were only four white inhabitants left.23 Arlindo Caldeira’s (1997: 108) portrayal of this white population in African cities paints a dismal picture of “strange, desperate beings, living in abject poverty but driven by the hope of sudden riches.” The social group that appeared to best integrated, in the sense of acquiring social status, was the fairer-skinned mixed-race population, particularly those with higher-than-average earnings (Caldeira 1997: 108).

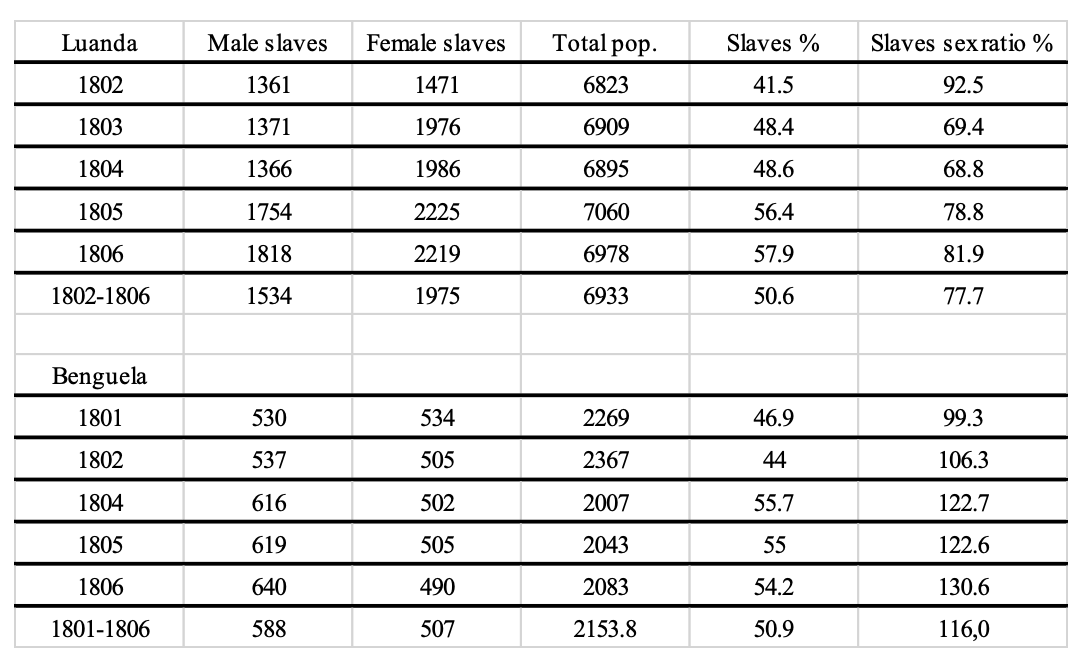

The small number of white people in cities in Africa was in direct contrast to the very high number of captive Africans. In Angola (as in Brazil) the proportion of slaves living in cities (c. 45%) was significantly higher than the average for the territory as a whole (16.7%). In 1802, 41.5% of the inhabitants of Luanda were slaves, but by 1802-1806, this number was already 50.6%. The same was true of Benguela, in that in 1802, slaves made up 46.9% of the population and, between 1801-1806, 50.9%. In the archipelago of São Tomé e Príncipe, in the city of the same name, 49.3% of the population was composed of slaves in 1771, and this number remained stable up until the end of the eighteenth century (Lucas 2015: 64).

What use was made of the slaves in the African cities of the Portuguese Empire? As was the case in the main urban centers in Brazil, such as Rio de Janeiro or Bahia, many of the captives were “wage-earning slaves” (escravos de ganho) frequently employed in labor and trade similar to that of the free population (e.g., as stevedores, sellers, construction workers, etc.) or as domestic servants (Karask 1997; Lara 2007). We do not have a precise breakdown of the number of slave-owning families in the African cities, but we do know that slave ownership was widespread and not confined to a wealthy minority. In the cities of the São Tomé and Príncipe archipelago, practically all the families, even those of modest means, owned slaves (Caldeira 1997: 110).

In Luanda, although many slaves were kept for domestic service, most was destined for export. This artificially increased the recorded population figures, although the registers do contain references to “departures” and confirm the significant annual fluctuation of captives as a result of trafficking (table 3). Notwithstanding, the number of slaves that remained in Luanda was significant. Most were female, which reflected the fact that more men were transported out than women, and that more women than men were kept for domestic service. Between 1799 and 1806, female slaves constituted almost a third of the population of the city (Curto and Gervais 2001: 35). Male slave labor, although statistically less common, was by no means insignificant. For example, in 1802, out of the 403 craftsmen residing in Luanda, 278 (69%) were slaves, and there were more master builders (mestres) who were slaves (56) than freemen (32).

The statistical weight of the slave population in Benguela was similar to that of Luanda, but with a male majority. For example, in 1806 there were 130 male slaves for every 100 enslaved females, unlike both Luanda and the city of São Tomé. Benguela was an important center for the trade of agricultural produce and minerals from the hinterland of the capitania, and that required a large workforce, particularly of stevedores, hence the high number of male slaves.24 Apart from these specific social factors (the low number of Europeans and the mass presence of slaves), Luanda, Benguela, and the city of São Tomé followed a similar pattern to urban areas, with a higher proportion of women and a low ratio of children under 14 years old. These urban areas had the lowest male-to-female ratios of the Portuguese Atlantic area. In the city of São Tomé, there were 64 men for each 100 women, whereas for the territory as a whole, the ratio was 103 to 100. In Angola, also due to the slave trade, there were more women than men (87.0%), but in Benguela (74.9%) and Luanda (81.6%) this excess balance was even more significant. These results are, at first sight, intriguing, given the large number of men employed in the administrative services, the armed forces, the church and in trade. They were, however, outnumbered by domestic staff (both free women and female slaves). The wealthy slave trading elite had huge contingents of domestic staff. Mariana Candido (2013: 117) describes the working lives of slaves in Benguela who, in addition to serving in all types of domestic activity, “also fanned their owners’ residences with portable fans night and day to cool rooms and chase mosquitoes away.”

The cities of Portuguese West Africa had the lowest percentages of children (0-14)25-between 20% and 24%-whereas in the surrounding territories the numbers oscillated between 27% and 30%. It might be supposed that this was due to the high number of slaves, who were normally adults with low reproduction rates, as was the case in several urban centers in Brazil. However, in fact, the opposite was true. In 1802, 19.3% of the youth population in Luanda was freeborn, whereas young slaves made up 23.4% of the youth population. In Benguela, the proportion was 23.2% and 24.4% respectively. Once again, the explanation for the reduced number of children in cities is to be found in the structure of households: a reduced number of married couples and a higher rate of single people working (voluntarily or otherwise) in the flourishing trade and commercial sectors or as domestic staff.

We close this section with a look at Portugal’s largest and most populated overseas territory. In Brazil, colonization expanded rapidly during the reign of Dom João III (1521-57), and by the end of the eighteenth century, it become the territory with the greatest demographic weight in the empire and home to most of the Portuguese Atlantic cities-12 in all. In the early 1800s, 72 out of every 100 residents of the Atlantic cities lived in Portuguese America. This chronology reflected both the demographic weight of the main cities and the process of expansion away from the coast into the vast interior areas, the effects of which led to the establishment of new cities in the eighteenth century (Oeiras, Mariana, and São Paulo; see map 1). The main exception to this trend was the captaincy of Minas Gerais, where deacceleration of mining activity led to rapid decline of the population of Mariana (Fonseca and Venancio 2014).

Brazil was home to the principal cities of the Portuguese Atlantic and was the territory that concentrated 88% of the effective computed demographic of the Atlantic area in 1800 (Matos, 2016). Rio de Janeiro, Bahia (Salvador), and São Luís do Maranhão were the only three cities in Portuguese overseas territories that had a population of over 20,000 inhabitants (cf. table 1 and 2).26 Rio and Bahia (Salvador) were large cities even by the standards of Portugal at the time and were particularly so when compared to other American cities. In Spanish America, in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, only Mexico City, Lima, and Havana had higher populations (Fernández-Armesto 2016:374). Even in North America, just Philadelphia and New York, with around 60,000 inhabitants each, outranked the largest Brazilian cities at the turn of the nineteenth century (Fonseca and Venancio 2014: 164). Given the disparities in the methodologies used it is not an easy task to compare the percentage rates of urban dwellers in the population in Brazil versus the US: nonetheless it has been suggested that the North American urbanization ratio was about 6% around 1790 (Boustan, Bunten, and Hearey 2013: 33). In Latin America, we can see, drawing on data compiled by Richard Morse, that Brazil had the second highest proportion of population living in cities (11.8%), behind Venezuela (16%) (Morse 1974: 438-442).

Twelve out of every hundred inhabitants of Portuguese America lived in cities. That is a considerable proportion given the extensive network of small towns (vilas) that existed in the colony; 118 vilas were established in the eighteenth century alone, 57 during the reign of D. José I (1750-1777) (Azevedo 1992). Of course, regional differences between the various captaincies persisted. Minas Gerais and Pernambuco had the lowest percentages (1.5% and 4.5%, respectively). In Minas, that was because important towns (vilas) such as Barbacena, São João del Rei, and Vila Rica were not classified as cities; in Pernambuco, the vila of Recife was one of the main urban centers of Brazil, but was only classified as a city much later, as stated above. On the other end of the scale were the captaincies of Maranhão (27.7%), due to the demographic weight of the city of São Luís and the absence of other urban centers, and the captaincy of Rio de Janeiro, given the concentration of people in the capital (27.9%).

In a study of the origins of colonial censuses in Brazil (1773), Dauril Alden (1963) states that unlike the Spanish Monarchy, the Portuguese Crown did not issue precise orders as to how inhabitants were to be classified, merely directing which age groups were to be registered. There is nevertheless a significant degree of homogeneity in the statistical tables of the various captaincies and cities in Portuguese America. The authorities, with a few notable exceptions (e.g., regarding indigenous groups), were able to survey the population and usually classified inhabitants as “white” (branco), “mulato” ou “pardo”27 (mixed-race) or “black” (preto), sub-dividing the last two groups into free individuals and slaves. These were precisely the same categories that local authorities in Western Africa used to register their populations.

In Brazil, as in most of the Portuguese Atlantic, white people were automatically considered free, with the category of slave being reserved for mixed race (pardos or mulatos)28 or black populations. The classification system also contained provision for intermediate social status (e.g., freed slaves) (Lara 2007: 131-135). In Brazilian cities, unlike Africa, no distinction was generally drawn between whites born in the Kingdom of Portugal (the reinóis) and those born in the colony. From the mid-eighteenth century onwards, the native-born white population outnumbered those born in Portugal (Silva 2011: 38). The colonial authorities did not sub-classify this group further unlike their Spanish American counterparts who used the term criollos to describe Spanish descendants born in the colonies, distinguishing them from white individuals born in Spain (Monteiro 2014: 125).

Freed slaves (libertos) who were invariably either mixed-race (pardo) or black (preto) were registered under a separate category in the cities. Freed slaves were subject to a specific legal regime, and it was therefore necessary to clearly distinguish them from free-born individuals. In 1779 the census for the city of Rio de Janeiro listed almost 9000 “freed slaves,” around 20% of the total number of inhabitants. This group was frequently stigmatized as being associated with indolence, vagrancy, and criminality, and therefore potentially dangerous (Lara 2007: 272-276). This growth in the number of freed slaves was not exclusive to Brazilian cities. Arlindo Caldeira (1997: 109) noted the emergence of this category in São Tomé e Príncipe, again with reports of involvement in delinquency.

In the last quarter of the eighteenth century, some population censuses in Brazil began to include a category for “Indians,” who, by the end of the colonial period, made up an estimated total of 6% of the population in Portuguese America (Alden 1984).29 The category was not, however, included for any of the 12 cities. That was probably due to the low number of Indigenous city dwellers. However, even in Belém (1785) there was not a single entry of an “Indian” individual, even though the Indigenous population of the captaincy of Grão Pará (of which Belém was the capital) was approximately 33% of the overall total (Mello 2015: 239). In the captaincies of Grão-Pará, Maranhão, and Paraíba, following the introduction of a directorate for the Indigenous populations (1759) subsequent to the expulsion of the Jesuits, several towns (vilas) were established specifically for Indigenous groups (Matos and Baltazar 2017). The urban way of life, particularly in the larger cities, did not attract Indigenous populations, and it was only towards the end of the colonial period that a clearer shift towards assimilation with Portuguese culture and habits emerged. The data indicates that, from the outset, the absence of Indigenous peoples was a characteristic that distinguished Brazilian cities from their Spanish American counterparts. We will return to that later. The question that then arises is how, from a quantitative perspective, did the cities in Portuguese America compare in terms of the populational characteristics described above? In general terms, although full indicators are not available for some of the cities (table 2), the results indicate a preponderance of white inhabitants and slave populations compared to semi-urban and rural areas. In terms of the white population, whilst it made up 31% of the total in Brazilian territory circa 1800 (Botelho 2015: 101), the percentage rate in the six Brazilian cities for which we have applicable data was higher: over 40% in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro and up to 50% in São Luís. That also applied to slave populations, which were more abundant in the cities. In 1800 around a third of the inhabitants of Brazil was enslaved, but for the seven cities for which we have consolidated data, only Paraíba (which is now João Pessoa) had a slightly lower value (28%). In Natal, Bahia (Salvador), Belém, and Cabo Frio this percentage rose above 40%.

The major presence of fair-skinned (white) people in Brazilian cities is well chronicled in the historiography. The fact that this segment generally did not exceed 40-45% is a typically colonial characteristic that has not always been highlighted in the literature. In the rural areas, particularly in plantation zones, the population weight of white Europeans was much more modest and the slave to slaveowner ratio tended to be much higher,30 as did the proportion of mixed-race freed slaves (mulatos or pardos). On the other hand, in the designated cities, the presence of colonial administrative and military staff and significant trade and commerce was reflected in a higher proportion of the population classified as white.

The historiography has emphasized the enormous scale of slavery in colonial Brazil, which was the European colony that imported the largest number of captives from Africa (Steckel 2010: 647). The high proportion of slaves in the main capitals, such as Bahia (Salvador) and Rio de Janeiro, at the end of the colonial period is already well established and has been thoroughly examined in several academic studies. Major works such as The Cambridge History of Latin America or Colonial Latin America recount these realities. However, the fundamental economic significance of slavery in the smaller Brazilian cities such as Cabo Frio, Belém, or even São Paulo has been somewhat overlooked. The slave population in these cities was around 40% at the end of the eighteenth century.

The proportion of enslaved individuals in Brazilian cities at the end of the colonial period was almost equal to that of the proportion of Europeans or people of European descent. In the case of the former capital of Brazil, Bahia (now known as Salvador), the number of slaves (14,695) was higher than the number of Europeans (10,720) by the year 1775. The largest number of enslaved people lived in Brazilian and not Spanish American cities, both in relative and in absolute terms. Burkholder and Johnson (2018: 151) argue that “slavery had a more urban character in Spanish America than in Brazil” in that “slaves constituted between 10 and 25 per cent of the populations of Caracas, Buenos Aires, Havana, Lima, Quito and Bogotá by the mid-eighteenth century.” We consider that, in the light of the data identified in this article, this affirmation merits revision, in that the proportion of slaves in the cities of Portuguese America fluctuated between 28% and 44%.

In Lisbon, Goa, and even Angra do Heroísmo, owning a slave was a status symbol that was within the reach of a small elite. In Brazil, São Tomé e Príncipe, or Angola, on the other hand, slave ownership was more financially accessible, and it had a broader economic significance. Owning a slave was, as a rule, considered to be a good investment, and lower-income groups, including freed slaves, used slave ownership as a means of savings or accumulation of wealth (Silva 2011: 43; Caldeira, 1997: 110).

Alberto da Costa e Silva (2011: 43) stresses the fact that the slave-owning character of Brazilian society extended beyond the very significant contribution of forced labor to the economy: “slaves were a central feature of day-to-day life.” In the cities, as referred to earlier, in addition to domestic slaves performing a range of services in the homes and estates of the owners, there were also “wage-earning slaves” who were employed in trade and services in return for a wage that they were obliged to share with their owners. Others were hired out as “chattel slaves” for various services, including public construction and supply services.

The high degree of participation of slave labor in heavy manual work, such as the construction of urban infrastructure and stevedoring, explains why there were more male than female slaves in all the Brazilian cities for which we have data. In São Paulo (1806), this male surplus was minor (101.4%), but it increased to 119% in Belém (1785), 136% in Rio de Janeiro (1789), and 155% in São Luís do Maranhão (1798). However, if the free population is taken into account, the values fall to 80% in Rio, 82.1% in São Paulo, 102% in Belém, and 112% in São Luis.31

To a considerable extent, therefore, slavery accounted for the imbalance between the genders in Brazilian society. The cities were no exception. In 1808, the ratio between the sexes in Brazil was 110%, oscillating between 98% for the free population and 141% for slaves (Botelho 2015: 96-97). In this context, all Brazilian cities had a gender ratio lower than 110%, in line with similar patterns in cities in other Portuguese Atlantic cities, which had a lower female presence compared to the surrounding non-urban areas.

In addition to the common shortfall of females (in particular, free women), cities in Brazil, as in other cities in the Portuguese Atlantic, also had a lower proportion of children (table 2). Very significant percentage variations were recorded for individuals aged 0-14, the lowest rate being 21% in Paraíba (João Pessoa), compared to 52% in Natal. Out of the eight cities for which we have data, six had ratios that were below the Brazilian average, which was 35.4% at the end of the eighteenth century. The pattern of lower rates of children in the cities generally reflected the fact (referred to earlier) that the cities attracted a greater number of unmarried individuals, mainly due to greater employment opportunities (or forced work) in the urban areas, including in colonial administration or military service. These individuals had a lower rate of reproduction. Even in the cities of Belém (1785) and Natal (1805), which were the only ones where the child population was higher than the Brazilian average, the percentage rate was still lower than that of the surrounding non-urban areas.

There were significant differences in the social composition of cities in Portuguese America and those of Spanish America. They did have some characteristics in common, in particular the high degree of miscegenation and cross-cultural encounters. They were in that sense quite distinct from the North American reality of settler cities where the rates of miscegenation were low. In most Latin American cities, the population was predominantly mestiço (mestizo) or black, and less than 40% white in most instances. Indigenous people were almost entirely absent from Brazilian cities, whereas in Spanish America the Indian population varied between 8.2% in Lima, 24.4% in Mexico City, and 66.7% in Quito.32 Conversely, the enslaved population was significantly higher in Brazilian cities.

Conclusions

Circa 1800, approximately 10.4% of the population of the Portuguese Atlantic lived in cities and we can reasonably estimate that a similar number lived in towns (vilas). Notwithstanding the vast socio-economic disparities between the territories, this overall figure is by no means low, particularly when compared with the figure for Portugal (11.6%) for 1801.

There was considerable asymmetry in terms of urban population between and, indeed, within the various territories. The ratio of the urban population of São Tomé e Príncipe was abnormally high due to the low overall number of inhabitants of the islands, but it was in the Azores and Madeira that the highest percentage rates were to be found (between 13 and 20%). In Angola, the cities of Luanda and Benguela accounted for just 5.3% of the inhabitants of the territory, even though Luanda was one of the main cities of colonial Africa. If we exclude the archipelagos, the highest rate of urban concentration was in Brazil (11.8%). Both Rio de Janeiro (the second largest city in the Empire, after Lisbon) and Bahia (Salvador) were the most populated cities in South America after Lima, in Peru. We are currently unaware of estimates for other empires during the same period based on common definitions and demographic sources. In any event, the data that are available to us suggest that Brazil had a higher concentration of population in the cities than Spanish America and considerably higher than North America.

The social distinctions made on the basis of skin color and legal status (i.e., free, freed, slave) were defining characteristics of colonial society, including the cities. The almost total absence of mixed-race, black, and slave populations in the Azores and Madeira sets them apart in this respect. In typical colonial cities, there was a prevalence of non-white population groups (both freed and enslaved), whilst these cities were simultaneously able to attract a greater proportion (compared to non-urban areas) of whites and had a greater ratio of slaves. Within this general pattern there were some clear differences. In Africa, the few white inhabitants were concentrated almost exclusively in the cities of São Tomé, Luanda, and Benguela, where slaves constituted almost half the population. In Brazil, on the other hand, following mass emigration from Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and as a result of lower rates of mortality for white settlers than in Africa, white populations formed up to 40% of the urban populations. It is highly probable that the colonial cities of Africa and Brazil had the highest slave populations of the European colonies in South America and West Africa. It has in the past been stated that it was in Spanish America that slavery was most concentrated in urban areas, but the data we have examined would suggest that in fact it was in Brazil. Other than in terms of social composition, the Atlantic coast cities did not diverge to any major extent from the main demographic characteristics of their European equivalents. Women formed a majority of the urban population (with the qualification that in Brazil they were a majority of the free population). That was largely due to the major presence of domestic staff in the cities. However, the role of women in these Atlantic cities needs to be re-examined given the suggestion in the historiography that they had a significant degree of involvement in running small businesses. Another relevant characteristic of the cities was the lower levels of child populations (<14) compared to non-urban regions. This was the result of the increased number of single people (crown servants, military personnel, seasonal workers) who had fewer opportunities to form stable family units and raise children.

Having considered the debate as to the criteria for definition of a city in the Portuguese colonial empire, the author adopted a political-administrative approach. For the purpose of this study, cities are urban areas that were formally designated as such by the Portuguese authorities during the colonial period. The author then set out a methodology for the demographic analysis of these cities based on existing statistical charts of the population for the late eighteenth century. The main contribution made to the historical study of cities is the provision of an empirical basis for demographic characterization of urban areas and their respective social, economic, and cultural contexts.

Social diversity was characteristic of urban areas in Latin America. The cities were home to Europeans and their descendants, mestiços (and other mixed-race populations), free and enslaved black populations, and, in Spanish America, Indigenous people. There were clear similarities between Brazilian cities and their Spanish American equivalents, but the distinct absence of indigenous populations in the former was a direct contrast with the latter. This difference can be explained by the fact that the colonization of Brazilian was heavily concentrated in coastal areas with an abundant contingent of slave labor for all types of work. Indigenous populations, according to political and administrative doctrines of the time, needed to be “domesticated” before being introduced into urban life.

In concluding this study across 20 cities and a broad range of demographic indicators, I consider that there are valid grounds for the development of two other lines of research to track the development of urban life in the Portuguese colonies. The first is related to the rapid growth of contingents of marginalized people. The presence of these people was noted and then systematically recorded in the Ancien Regime sources, and these groups were considered as potentially disruptive to the established order. The second potential line of enquiry is research into the occupational profile of city dwellers. That might offer highly relevant perspectives on the characterization and differentiation of cities, both within the Atlantic areas and in comparison, with other colonial realities. It is not uncommon for reference to be made in the records to occupational structure and employment categories (as is also the case in the Spanish Empire), and this line of inquiry will certainly provide further valuable insight into urban dynamics.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Carmen Alveal, Carlos Bacellar, Javier Luis Alvarez Santos, and Tarcísio Botelho for their assistance in clarifying innumerable doubts as to the legal status of certain cities and the limits of the urban parishes. Jonathan Roberts translated the text from Portuguese. For all possible errors, however, only the author may be held responsible. The translation of this text was supported by FCT through the Strategic Funding of the R&D Unit CIES-Iscte, Ref. UIDB/03126/2020.

Primary Sources

Azores Islands

A1 - Totals (1807-09) - Matos and Sousa (2015a).

A2 - Angra do Heroísmo (1807-1809) - Biblioteca Pública e Arquivo Regional Luís da Silva Ribeiro (Island of Terceira, Azores, henceforth B.P.A.R.L.S.R.), Capitania-geral, População, Ilha Terceira (1795-1830).

A3 -Ponta Delgada (1807-1809) -B.P.A.R.L.S.R.), , Capitania-geral, População, Mapas da População (1795-1815). Ilhas de São Miguel e Santa Maria.

Angola

B1 - Kingdom of Angola (1800) - Matos and Vos (2013).

B2 - Benguela (1798) - “Mapa dos habitantes que existem na capitania de Benguela em o ano de 1798,” Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (henceforth AHU), Angola, box 89, doc. 88.

B3 - Benguela (1801) - “Mapa dos habitantes que existem na parochia de Benguela em o ano de1801,” AHU, Angola, box. 103, doc. 1.

B4 - Benguela (1802) - “Mapa dos habitantes que existem na capitania de Benguela em o ano de 1802,” AHU, Angola, box 107, doc. 30.

B5 - Benguela (1804) - “Mappa da cidade de Benguela e suas mais próximas vizinhanças [...] em o anno de 1804,” AHU, Angola, box. 111, doc 6.

B6 - Benguela (1805) - “Mappa da cidade de Benguela e suas mais próximas vizinhanças [...] em o anno de 1805,” AHU, Angola, box 115, doc 28.

B7 - Benguela (1806) - Mappa da cidade de Benguela e suas mais próximas vizinhanças [...] em o anno de 1806,” AHU, Angola, box 115, doc 28.

B8 - Luanda (1781) - “Relação dos habitantes desta Cidade de São Paulo de Assunção do Reino de Luanda do Reino de Angola no ano de 1781, AHU, Angola, box 64, doc. 64

B9 - Luanda (1802) - “Mapa de toda a Povoação de São Paulo de Assunção de Luanda em todo o ano de 1803 [...],” AHU, Angola, box 105, doc. 44.

B10 - Luanda (1803) - Mapa de toda a Povoação de São Paulo de Assunção de Luanda [...] em todo o ano de 1804 [...],” AHU, Angola, box 105, doc. 44.

B 11 - Luanda (1804) - Mapa de toda a Povoação de São Paulo de Assunção de Luanda e de suas diferentes corporações [...] em todo o ano de 1804 [...],” AHU, Angola, box 112, doc. 47.

B12 - Luanda (1805) - Mapa de toda a Povoação de São Paulo de Assunção de Luanda [...] em todo o ano de 1805 [...],” AHU, Angola, box 115, doc. 27.

B13 - Luanda (1806) - Mapa de toda a Povoação de São Paulo de Assunção de Luanda [...] em todo o ano de 1806 [...],” AHU, Angola, box 118, doc. 49.

Brazil

C1 - Totals (1800) - Botelho (2015: 96-102); Marcílio (1984: 49).

Bahia (Salvador)

C2 - (1775) - “Mapa geral no qual se vêm todas as moradas de casas que há na Cidade da Baía [...] Junho de 1775,” AHU, Bahia, box 47, docs. 8810-8815.

C3 - (1781) - “Mapa da enumeração da gente e povo desta Capitania da Baía [...] ano pretérito de 80 para 81 [...],” AHU, Bahia, box 58, doc. 11138-11140.

C4 - (1782) - “Mapa da enumeração da gente e povo desta Capitania da Baía, [...] ano pretérito de 80 para 81 [...],” AHU, Baía, box 58, docs. 11138-11140.

(1759-1807) - Mattoso (1992: 107).

Belém

C5 - (1785) - “Mapa de todos os Habitantes, e Fogos que existem em todas, e em cada uma das Freguesias, e Povoações das Capitanias do Estado do Grão Pará, ao 1º de Janeiro de 1778,” AHU, Grão Pará, box 94, doc. 7509.

Cabo Frio

C6 - (1789) - “Mapa geral das cidades, vilas e freguesias que formam o corpo interior da capitania do Rio de Janeiro com declaração do número de seus templos, fogos, etc,” Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geographico Brasileiro, XLVII, part 1 (1884), Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional (27-30).

Natal

C7 - (1805) - “Mapa da População da Capitania do Rio Grande do Norte [...] 31 de Dez(em)bro de 1805,” AHU, Rio Grande do Norte, box 9, doc. 623.

C8 - (1805) - “Mapa geral da Importação, produções e Manufaturas do Reino” [...], AHU, Rio Grande do Norte, box 10, doc. 629.

Paraíba (João Pessoa)

C9 - (1802) - “Mappa dos habitantes que existem na Parrochia da freguezia de Nossa Senhora das Neves da Paraíba do Norte em o anno de 1802,” AHU, Paraíba, box. 41, doc. 2890.

Rio de Janeiro

C10 - (1779) - Resumo total da população que existia no anno de 1779 [...], Revista do Instituto Histório e Geographico Brasileiro, XXI (1930), 2nd edition, Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional (216-217).

C11 - (1789) - “Mapa geral das cidades, [...],” Revista do Instituto Histório e Geographico Brasileiro, XLVII, part 1 (1884), Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional (27-30).

C12 - (1796) - “Extracto da população da capitania do Rio de Janeiro em 1796,” AHU, Rio de Janeiro, box 160, doc. 12026.

São Paulo

C13 - (1798) - Marcílio, 1974, p. 100-101.

C14 - (1798) - “Mappa geral dos habitantes da capitania de São Paulo no anno de 1797,” AHU, São Paulo, box 65, doc. 5003.

C15 - (1803) - “Mappa dos habitantes que existem na Capitania de S(a)m Paulo em o anno de 1803,” AHU, São Paulo, box 24, doc. 1108.

C16 - (1805) - “Mappa geral dos habitantes da capitania de São Paulo [...]no anno de 1805,” Biblioteca Nacional do Rio de Janeiro, Secção de Manuscritos, I-32-0-6.

C17 - (1806) - Population tables of São Paulo’s parishes (1806), Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo, Mapas de população

[http://www.arquivoestado.sp.gov.br/uploads/acervo/textual/macos_populacao/033_021.pdf].

Sergipe (Aracajú)

C18 - 1809 - Alden (1987: 288).

Olinda

C19 - (1789) - “Mapa que mostra o número dos habitantes das 4 capitanias deste governo [...],” AHU, Pernambuco, box 178, doc. 12472.

Cape Verde

D1 - Ribeira Grande (and archipelago of Cape Verde).

D2 - (1779) - “Extracto da Consulta do Conselho do Ultramar [...] sobre as ilhas de Cabo Verde,” AHU, Cabo Verde, box. 39, doc. 10A.

Madeira

Funchal (and archipelago of Madeira)

E1 - (1797) - “Mapa Geral da população das Ilhas da Madeira e Porto [...] 1797,” AHU, Madeira, box 2, doc. 996.

São Tomé e Príncipe

Totals, Cidade de Santo António and Cidade de São Tomé:

F1 - (1770) - “Sumária relação dos habitantes desta ilha, e cidade de São Tomé [...], AHU, São Tomé e Príncipe, box 13, doc. 22.

F2 - (1771) - “Relaçam sumaria dos habitantes desta cidade de Santo António,” AHU, São Tomé e Príncipe, box. 13, doc. 4; and “Rol dos habitantes da ilha de São Tomé,” AHU, São Tomé e Príncipe box 13, doc. 22.

F3 - (1777) - “Relaçam de todas as pessoas brancas, pardas, e pretos forros e captivos [...], AHU, São Tomé e Príncipe, box 13, doc. 22

F4 - (1777) - Populations lists of São Tomé Island, AHU, São Tomé e Príncipe, box 16, doc. 44.