Introduction

For readers less used to the theme addressed in this article, it is important to first understand the main characters analyzed here. Bandeirantes is the name given to some of the former inhabitants of the captaincy of São Vicente, a Portuguese held territory in the Americas, now part of the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Also called sertanistas, they undertook expeditions towards regions far from the São Vicente captaincy, the so-called sertões. Sertão was the generic way the Portuguese described distant, not yet conquered, “wild” areas. The main aim of these incursions into the sertão was to find areas densely populated by indigenous people, who were imprisoned and taken by the sertanistas back to their villages in the captaincy of São Vicente to be enslaved by the residents. In other words, the devastation of the sertão to obtain enslaved indigenous workers was the purpose of these bandeiras, which took place mainly towards the west, reaching the Spanish dominions in America, along the borders of the provinces of Río de la Plata and Paraguay, from 1585 to 1650.

An interesting point to start to reflect on the connections between the Spanish and Portuguese dominions in the region covered is to look at the way a book on colonial São Paulo was presented when a Spanish translation of it was published in Argentina in the twentieth century. This is Affonso de Escragnolle Taunay’s book, translated as San Pablo en el siglo XVI: Historia de la villa de Piratininga by “Alfonso Taunay” (Taunay 1947). Taunay was one of the responsible for the heroization of the bandeirante, a project carried out by the author between the 1920s and 1950s. He did this through his work as director of the Paulista Museum, a position he held between 1917 and 1945. This museum, also known as the Ipiranga Museum, is one of the most visited in the country. It was built at the end of the nineteenth century, as a kind of museum-monument. Both the building and the hill where it is located symbolize an event where an important act for the success of Brazil’s independence is believed to have occurred. A few decades after its foundation, during Taunay’s term as director, the inside of the museum was filled with exhibits, scenarios, and narratives that materialized the discourse of a bandeirante epic, something which continues to be represented inside the museum.2

The proposal to disseminate and praise the achievements of the ancestors of some paulistas was completed by the historiographical work of Taunay, who wrote dozens of books in addition to directing the compilation and publication of numerous documents deposited in foreign archives related to the history of colonial São Paulo (especially from Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain). Taunay was part of a generation of local authors who wanted the narrative of São Paulo’s regional history to become a narrative of Brazilian history, justifying the idea that São Paulo had a kind of manifest destiny to lead Brazil (Ferretti 2004: 161-162). This line of analysis was based on the idea that such principles had existed since the foundation of the city when the sertanistas acted to expand the frontier, a maxim that has been denied by generations of later historians (Glezer 2007; Monteiro 2000).

To open this article, we will examine an interpretation that appeared in the translation of one of Taunay’s books in Argentina. It is a way of framing connections and drawing parallels between the Spanish and Portuguese parts of South America. On the Spanish side, there was a circuit composed of the provinces of Paraguay and Río de la Plata, headed by the cities of Asunción and Buenos Aires. In the Portuguese area, within the captaincy of São Vicente, the vilas of São Paulo and Santo André da Borda do Campo, in the interior, were linked to the port of Santos, on the Atlantic coast. Rubén Franklin Máyer, author of the preface to the Argentine edition, highlighted the similarities between Buenos Aires and São Paulo, at that point in the twentieth century already established as important Latin American metropoles. According to Mayer, the comparison between the cities could also be found in their colonial past. These similarities are due to the fact that both São Paulo and Asunción were nuclei formed by white men, enslavers of indigenous people (Taunay 1947).

It can be argued that these men were probably not as white as some have attempted to argue in the historiography, given that, in addition to enslaving indigenous people, they also had sexual relations with indigenous women (through official marriages, extramarital relationships, and non-consensual intercourse). In any case, what we want to highlight in this introduction is not only the similarities between these frontiers of colonial expansion, but also the elements that connected them. More precisely, the theme of this article is the movement of men from the captaincy of São Vicente towards the provinces of Río de la Plata and Paraguay in the early decades of the seventeenth century. The bandeiras constituted the main modus operandi of this movement in the analyzed period. It is important to note that the transit was not one-way. The routes originated in São Paulo and other vilas in São Vicente, running to the Spanish parts of America and involving a few hundred Portuguese accompanied by groups of Tupiniquim, who at their largest formed forces between 1,000 and 2,000 strong. The heart of this transit were the commercial connections (legal and illegal) that linked the Portuguese and Spanish territories, as well as the process of war, plunder, and enslavement of the indigenous people who inhabited these domains to supply labor to the captaincy of São Vicente. This was the meaning of the bandeiras, expeditions carried out by the “hombres de San Pablo” or “mamelucos de San Pablo,” sertanistas, as they were called during the period analyzed in this article, a process studied by John Manuel Monteiro in his already classic work, Negros da terra: Índios e bandeirantes nas origens de São Paulo (Monteiro 2000).3 On the other hand, it is worth highlighting the traffic in the opposite direction: the migration of the indigenous population from Paraguay and Río de la Plata, especially of Guarani, who were transferred by force to Portuguese America through the actions of bandeirantes (Sposito 2012; Melià 1988). Finally, the commercial and wedding alliances that linked the Spanish and Portuguese on both sides of southern America caused many Spanish residents to leave Paraguayan settlements on the frontier between the Empires and, strengthening these ties, to migrate to the Portuguese side to live in the vilas of São Vicente (Vilardaga 2010: 229-242; Quarleri 2009: 70-71).

Having presented some of the main aspects that demonstrate these connections, here are some questions for which we will present hypotheses throughout this text. The main issue is to try to understand why the destruction of Guairá by the Portuguese, an important indigenous area, who lived in aldeias under control by Jesuits or in the forests in independent aldeias, occurred precisely during the period of the union of the Iberian Crowns (1580-1640).4 Was it a mere temporal coincidence, or would evidence of other movements, not so evident when analyzing the history and historiography of the region, be revealed? Was there, on the part of the Spanish administration, a tolerance of the circulation of Portuguese in the Castilian dominions in America? Was this permissiveness the reason for the bandeiras to have developed and had their peak in this period (1585-1650)? This leads us to ask, finally, if there was an incentive, or tacit support of the crown in relation to bandeirante activity.

Mapping the Terrains

Encountering lands full of riches, or the hope of being able to find them, boosted the conquest of America by Europeans. Attempts at colonial rule-led by the crowns and carried out by adventurers and colonial authorities-were directed towards promising regions, where it was believed that there would be an abundance of precious ores or profitable products to be extracted and traded in world markets. Obviously, the history of the Americas is not limited to the action of the conquerors or the finding and exploitation of colonial wealth. For this to work according to European intentions, finding explorers of the new lands, climates, and seas was necessary, as were people who already knew them. European domination was established through battles and negotiations and peace treaties between indigenous peoples and Europeans, as the invaders needed those who provided them with knowledge about the territory and its paths. In turn, access to products that would bring wealth to Europeans was only possible if there were workers to bring these products to the conquerors’ hands. There was, therefore, a need for indigenous guides, ambassadors, interpreters, workers, porters, farmers, and miners to make the mirages glimpsed by Europeans a reality, as Michael Witgen also showed in relation to British colonization in North America (Witgen 2012). It was essentially indigenous labor that produced the wealth taken from America, though in various parts of the continent, native labor was later replaced by African workers. The forms of exploitation of the indigenous people varied, using persuasion and violence to obtain work, which was exploited through different regimes, from the payment of taxes by free communities to the legal or illegal enslavement of natives.

The Río de la Plata region owes its name to a certain “geographical lapse,” the distance between European desire and American reality. The estuary of the Río de la Plata, which presented itself as a promising gateway for European navigators, was not initially the opening to a land of wealth that explorers longed for. It was officially discovered by Captain Juan Solís in 1517, who found there information about and even a few traces of a “silver mountain,” which the invaders would actually only discover some decades later in distant Peru. Even though the silver was not originally from there, it was through the trade and circulation of Peru’s silver that the region gained prominence with official and clandestine transactions from the seventeenth century onwards (Moutoukias 1988; Schwartz 2008).

Authors like Moutoukias and Schwartz have been working for some decades on the importance of understanding commercial circuits outside the official routes. Buenos Aires was not officially the main port in Spanish America, since prominence was given to the Lima-Seville single port regime. In any case, the quantity of silver, enslaved Africans, and sugar was quite considerable, in addition to products made and exchanged locally in America and goods imported from Europe, consumed by colonial elites. According to Schwartz, the jewel of both the Spanish and Portuguese Crowns was silver, which sustained the Iberian Union and the development of both Empires in the first decades of the seventeenth century (Schwartz 2008). Atlantic routes thus connected Buenos Aires to Salvador, Rio de Janeiro, and Luanda, linking this circuit, in turn, to the two ends of the system-the silver mines in Peru and the European metropoles.

However, what about the internal routes, the land and river routes that connected the Provinces of Paraguay and Río de la Plata to the captaincy of São Vicente? The land route linking Buenos Aires to Lima and Potosí mostly ran through the province of Tucumán to the West, thus not running through the territories of Río de la Plata or Paraguay. The area focused on in this article initially refers to the province of Paraguay, which in 1618 was split into two: while one was centered in Asunción and kept the name “Paraguay,” the other, the province of Río de la Plata, came to confirm the prominence that the Plata region had achieved. The capital of the province was the city of Buenos Aires.

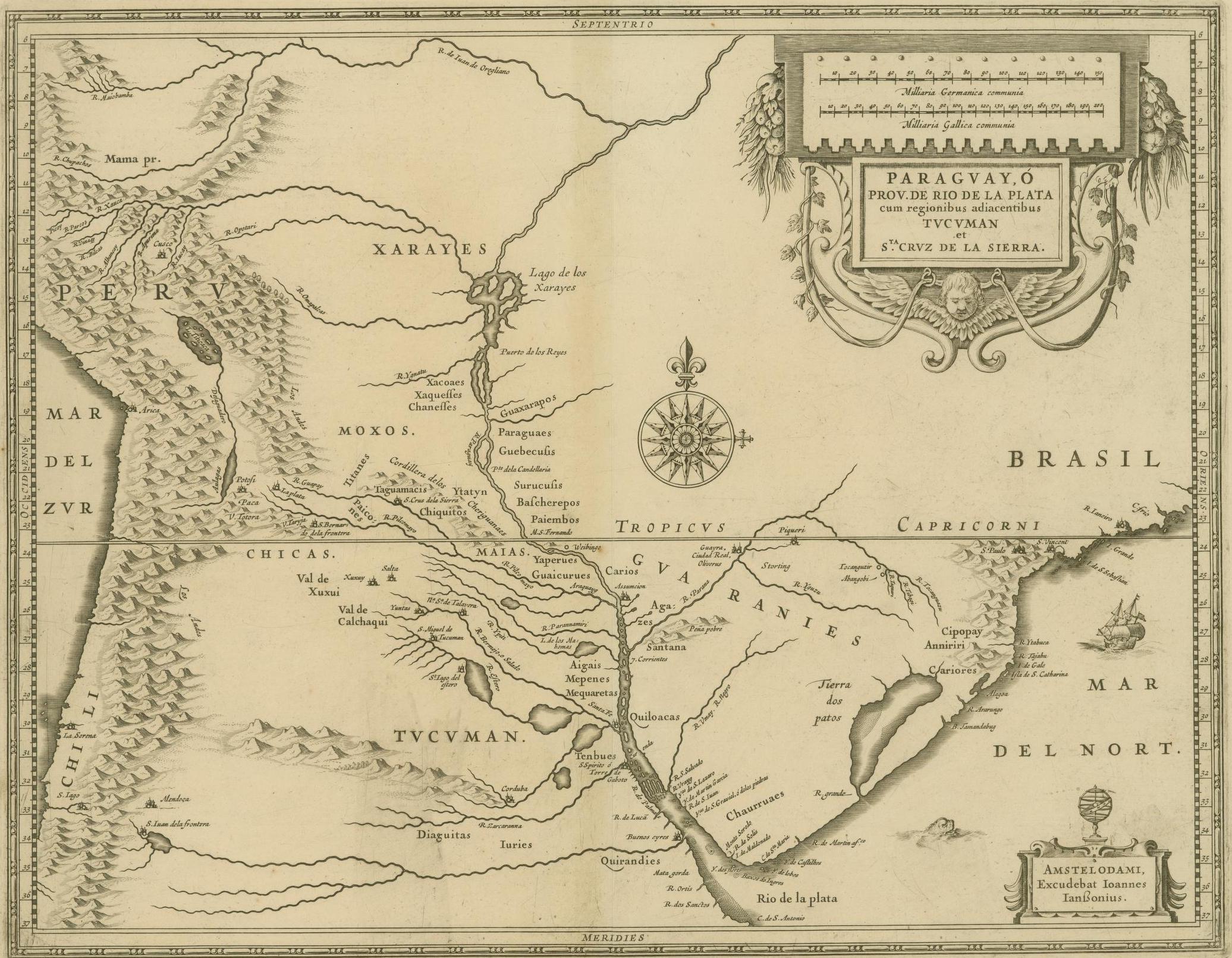

A century later, Europeans had gained more knowledge about the interior of the territory, but this did not mean they fully dominated it or had access to all of it, as the following map indicates (Image 1). The Plata estuary opened the interior of the continent to navigation, but this was not an accessible route. On the one hand, there was considerable indigenous resistance on the land route, from the Guaicuru and Mbaya, for example. On the other, navigation on the Paraguay river and its tributaries was hampered by the Paiaguá. indigenous resistance blocked the advance of the Europeans through the provinces of Paraguay and Río de la Plata, while adverse terrain-formed by the swampy region of Mato Grosso, steep mountains in Bolivian territory and, finally, by the Andes Mountains-functioned as impediments. In addition to the crown’s prohibition and the difficulties of the route, this overland route through Paraguay would only be followed in a clandestine manner and on a much smaller scale compared to the route to Buenos Aires through the province of Tucumán.

Image 1: Paraguay, ó Prov. de Rio de la Plata cum regionibus adiacentibus Tucuman et Sta. Cruz de la Sierra. Joannes Janssonius, 1630 [Original in the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. Authorized]

Just over two thousand kilometers north of Buenos Aires and accessible from other coastal vilas in the Atlantic, São Paulo de Piratininga had its foral recognized in 1560. It was one of the first Portuguese settlements founded away from the coast, breaking with the initial Portuguese pattern of the first century of the colonization of the Americas. Departing from the vilas of São Vicente (1531) and Santos (1546), the colonizers followed routes and interests of the continent’s own natives and discovered a promising region beyond the Serra do Mar, a mountainous region that separates the coast from the interior of the territory. Although isolated by the mountain range, as also represented on the aforementioned map (Image 1), the idea of the vila of São Paulo as an autonomous space, detached from the other colonial nuclei, was never real. To the contrary, studies of colonial São Paulo allow us perceive the transit of its residents towards various parts of the Portuguese domains (Blaj 2002; Monteiro 2000), including their entering into Spanish spaces in the Americas, the object of this article. Thus, crossing the fields of Santo André, at the edge of the Serra, “à borda do campo” (in English, “at the edge of the field”) the Piratininga plateau was reached, where the Jesuits built their Casa Professa. Centuries later, this Jesuit house or college was the place chosen to represent the beginning of the Portuguese conquest in that region. The complex formed by the São Vicente coast, Serra do Mar, the fields of Santo André, and the Piratininga plateau created an interconnected space, which projected the circulation of men and goods beyond the coastal zone.

In turn, the colonization of the provinces of Río de la Plata and Paraguay demonstrates in a similar way the connection between the coastal and inland nuclei as a strategy for dominating the continent. The initial foundation of Puerto de Nuestra Señora Santa María del Buen Aire had failed in 1536 due to the enmity that the Querandi, the natives of the area, had towards the Spanish invaders.5 Buenos Aires would be refounded in 1580. On the other hand, the opposite happened in Asunción. Since 1537, the Guarani (called “Cário”) who resided there had commercial and family alliances with the Spanish, which made the Asunceño settlement a base of support, both for the expansion of the Spanish frontiers eastwards and for the refoundation of Buenos Aires a few decades later (Neumann, 1996: 114).6

The province of Guairá (part of the province of Paraguay) was the object of intense disputes involving Spanish, Portuguese, and indigenous people during the first decades of the seventeenth century. It was located exactly at an intersection point within this vast territory that separated the Portuguese and Spanish dominions. To situate it geographically, it is useful to know that it is located in what is today the northwest of Paraná, a Brazilian state, in the territories where the Paraná, Paranapanema, and Iguaçu rivers converge. The frontiers between the Portuguese and Spanish Empires from north to south were negotiated and established only in border treaties during the eighteenth century. We should point out that the frontiers between the Empires would only begin to be defined when both kingdoms actually decided to establish projects and allocate resources to the region. This happened, for example, through the treaties of Utrecht (1714-1715) and the refounding of Colonia del Sacramento (1716), which led to a rearrangement of the local forces (Prado 2015; Garcia 2012; Herzog 2015).

Before that, the frontiers had been fluid for two hundred years, since the possession of American territory by Europeans depended on the conquest of native populations, as well as being able to access them whether by sea, river, or land, and on obtaining wealth and a labor force that could be mobilized to permit settlements along the Empires’ frontiers (Langfur 2014; Vilardaga & Sposito 2018). This made it possible for towns, fortifications, and cities to be built and maintained (Erbig Jr. 2015).

For almost twenty years within the period analyzed, Guairá was the only bastion of Spanish conquest in the region, expanding eastwards from Asunción. This region was formed by the cities of Ontiveros, Ciudad Real de Guairá, and Vila Rica del Espirito Santo, in addition to the 13 missions created by the Jesuits among indigenous peoples. It comprised a vast territory occupied by numerous Guarani societies. The Jesuit Diego Torres stipulated in 1610 that there were around 400,000 souls between Guairá and the Tibagi river, a number that was confirmed from estimates made by the anthropologist Bartomeu Melià (1988: 49-59, 88-89).7

Colonization began in the region around 1554, when the Guarani chiefs of Guairá proposed an alliance with the Spanish, which marks the entry of colonizers in their lands (Díaz De Guzmán 1980: 198). Coincidentally, it was then that Jesuit priests began to establish their missions on the heights of the Piratininga plateau, in another part of southern America, as previously stated. Thus, two movements like these, which occurred discontinuously and without any direct connections between them, denote strategies of domination of the territory by Europeans that raise questions. As Vilardaga (2010: 205) mentioned, using a beautiful metaphor, the steps of the Portuguese and Spanish on the borders of the Empire indicate moves as on a chessboard, in which each step triggered actions and reactions from the opposite side and whose final objective was the conquest of territories for their respective crowns. While we appreciate his analogy, we suspect that this game of chess did not occur so consciously and deliberately on the part of its players. Using this figure of speech, before the Portuguese and Spanish played against each other, they had to deal with their own situations, internal to each of the colonization models, in addition to interacting with the dynamics in each of the regions they tried to conquer.

In this sense, we emphasize that two indigenous societies, through the power of the political connections of their leaders, enabled the expansion of Europeans in São Vicente and Paraguay. On the one hand, the Spanish occupation would, in an unconscious and planned manner, follow the steps of the Guarani. From Asunción, a “Cário” (or Guarani) region, it headed towards Paraná, Iguaçu, Guairá, Tibagi, Uruguay, and Tape. This toponymy, which bears the names of rivers, plains, plateaus, and mountains in the west/east direction, are also names of Guarani indigenous societies (Susnik 1979-1980: 16-17). In the Portuguese case, colonization would essentially spread along the Atlantic coast in the territories of speakers of Tupi languages, the Tupi-Guarani family. Obviously, the identification of indigenous collectives as “Tupi” is a simplification regarding the diversity that characterizes these indigenous groups. However, anthropology itself operates within this categorization, which was also recognized by linguistics when classifying different ethnic groups as speakers of the “Tupi” linguistic trunk. Thus, at the time of the European conquest, the captaincy of São Vicente’s coast was a region of Tupiniquim, Tupinambá, and Tamoio, all belonging to the Tupi trunk.

At the same time, one cannot lose sight of the fact that Guarani societies not only helped to define the paths and destinations of Spanish colonization but were also part of Portuguese interests and routes. Manuel da Nóbrega, the provincial of the Society of Jesus in Brazil, who landed in Salvador in 1549, soon became interested in the people who lived in the region in Paraguay. According to him, the Spanish had been establishing large plantations with disciplined labor. In his view, this was what Portuguese colonization needed, so the solution might be for Portugal to direct its efforts towards the conquest of land in that region (Nóbrega 1931: 174-175). Not by chance, the Jesuits spearheaded the occupation of São Paulo. Decades later, it would also be Jesuits sent by Spain who would advance in the conquest of the Guairá peoples and other missionary regions, such as Itatim, Tape, and Uruguay. In the future, the frontiers of Portuguese and Spanish colonization would collide in those lands. The residents of São Paulo also realized that the greatest wealth they could exploit in those lands was obtained through the war and the capture and enslavement of indigenous Guarani from Paraguay and Río de la Plata.

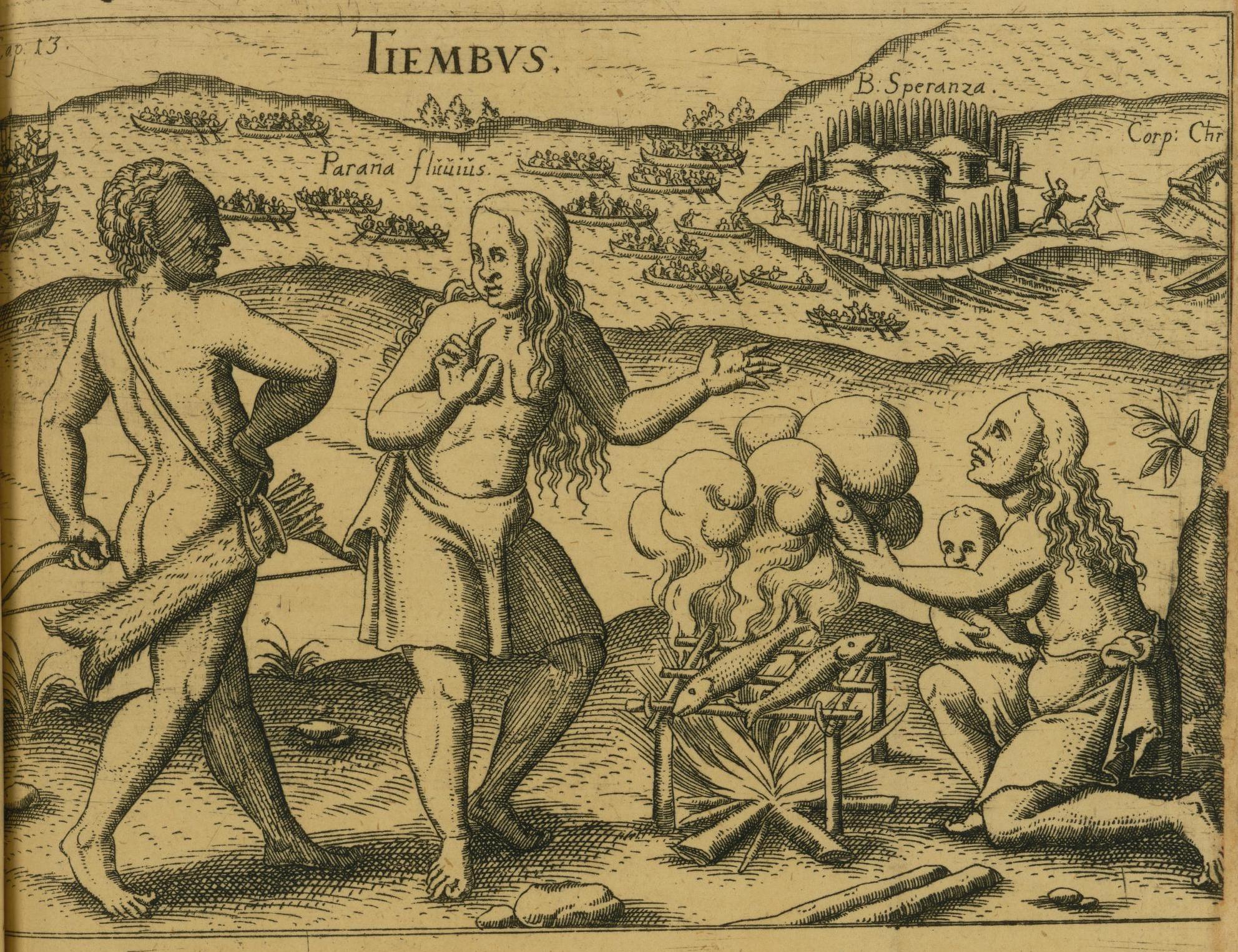

Thus, in the vast region that separated the two empires, the richness of the sertão that was sought and desired in the first decades of the seventeenth century was not precious metals nor profitable products in the commercial circuit, such as silver, sugar, or tobacco. Along the frontiers between the empires, the point of contention between Spanish and Portuguese colonizers, and of these in relation to the priests, was access to and control of indigenous labor, especially the Guarani (Valadares 1993). This interest is attested to in two documents produced between the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth. On the one hand, the aforementioned map (Image 1) illustrates the Guarani’s striking presence on the frontiers between the two empires. The other is an engraving by the German-born explorer Ulrich Schimdl. He visited both regions, produced an image of abundance, docility, and the high demographic concentration of the peoples who lived in the Paraná River region, a Guarani territory, as represented in Image 2.

Image 2: Native Americans from Paraná River. Sammlung. Pt 4. in Americam. Ulrich Schmidel, 1599. (Original in the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. Authorized)

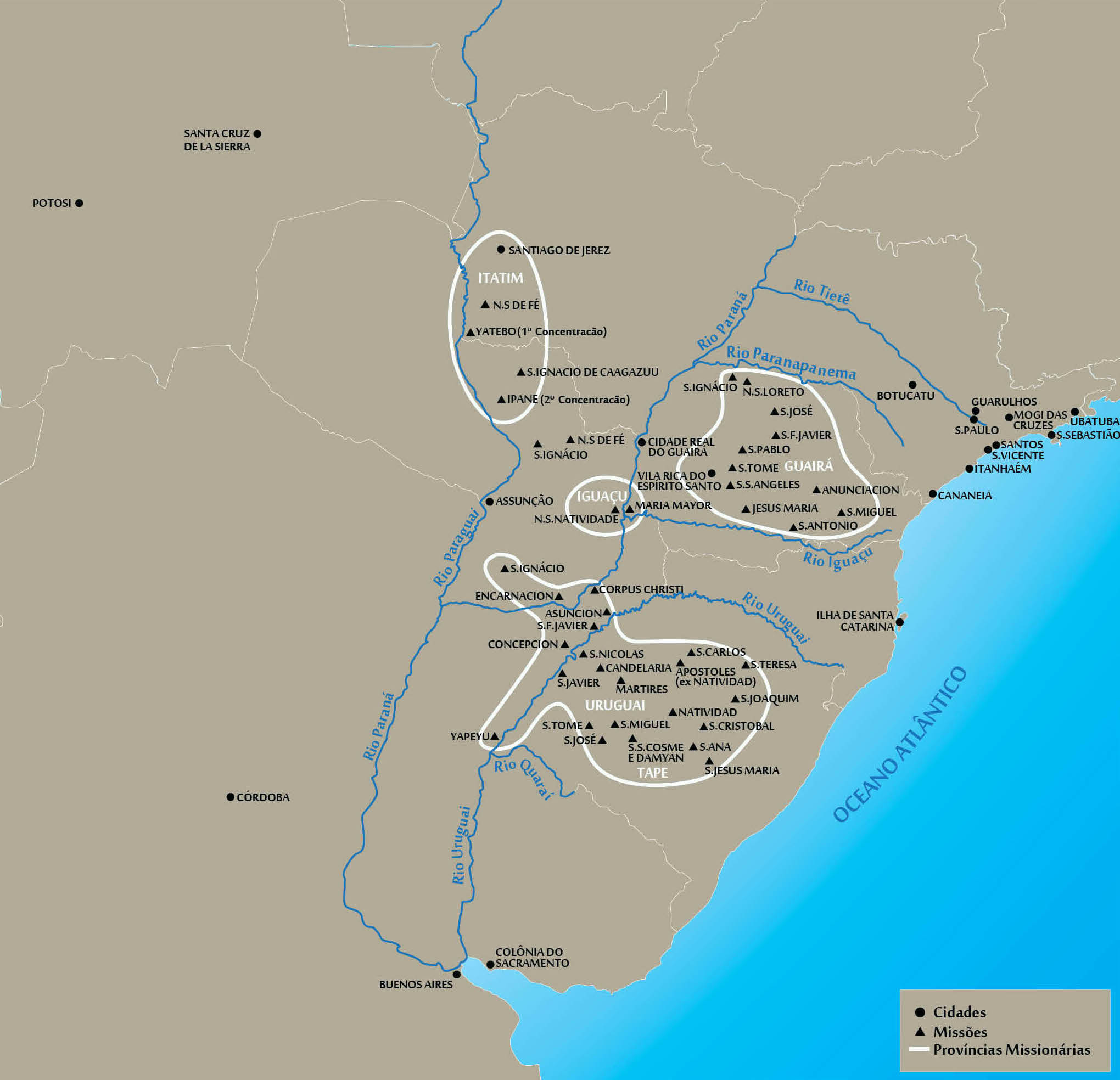

The bandeiras sent into Guairá are believed to have resulted in the enslavement of 60,000 indigenous people, who were brought in chains along the overland paths, crossing the Paraná and Tietê rivers, led by the bandeirantes only between 1629 and 1631 (Melià 1988: 88-89; Monteiro 2000: 68-76). The Guarani were semi-nomadic and, like other indigenous people in the Americas at the beginning of Portuguese colonization, they cultivated products such as corn and manioc, also called “farinha de pau.” This was one of the factors that made them more adapted to the large-scale production of food and inputs for the colonial world, according to the European vision of how indigenous labor should be organized. In addition, as already mentioned, the high demographic density of Guarani in the region meant that the territory of the Jesuit missions and their surroundings constituted a favorable space for obtaining this kind of labor. After all, within the missionary model, indigenous people lived in confinement, where they were taught Western ways and adopted practices of the Christian faith (Haubert 1990; Kern 1982). Finally, the fact that Guarani is one of the Tupi languages also functioned as a factor of attraction for the Portuguese, especially those from São Paulo already versed in the “general language,” an adaptation made by the colonizers from the various Tupi languages spoken on the Brazilian coast (Altman 2003). On the following map, the main locations are highlighted, among villages, cities, and Jesuit missions, as well as the rivers that made up this path towards the wealth of the sertão found there, the Guarani peoples (Image 3 and Image 4).

Image 3: Mapping of Portuguese and Spanish occupations at the boundaries between the Empires. (Author Mila Costa. Authorized)

From the issues raised, it is possible to perceive the permeability of this border area, demonstrating some aspects of transit and conflicting relations between the inhabitants of the different parts that formed these territories (Vilardaga 2010; Sposito 2012; Herzog 2015). It is worth reflecting on to what extent the Iberian Union, a result of the vacancy of the Portuguese throne after the death of D. Sebastião in 1578, had an impact on a greater integration between the Empires by carrying out the much discussed project of a universal monarchy that would dominate the world (Lima 2010). In fact, the Spanish Empire now formed a world “where the sun never set,” in reference to the territories of Spain in the East and in the Americas, as Charles Boxer recalled (Boxer 2002: 122). It remains for us to understand what this proposal of imperial universality would have meant for a potentially conflictual region of frontiers between the Spanish and Portuguese Empires.

Imperial Union: Aggregating Interests, Stoking Conflicts

When we speak of empire, we need to recognize how much anachronism this term bears (Bicalho 2009; Fragoso and Gouveia 2010; Fragoso and Monteiro 2017). John Elliot uses this word to study Spanish and British overseas expansions in the modern world. However, he does not shy away from discussing the risks of applying national projects from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to the colonization of the Americas in the early modern age. Thus, by problematizing the historicity of the concept of empire, Elliot highlights the refusal of Charles V and Philip II, kings of Spain, to assume the title of “emperor,” which was linked to Christianity and the leader of the Catholic Church (Elliot 2006: 119-121).

At the same time, it is also necessary to realize that any other expression or word to refer to European expansion in the Americas will usually incur anachronism. Michael Witgen, for example, has questioned how the expression “Atlantic World” or “New World” carries a number of values. It is as if the Native Americans were on the continent only to be integrated and controlled by European colonial powers. In response to this view, recognizing the importance of indigenous social organizations and the ways in which they negotiated the geographical and social spaces of colonization, Witgen proposes the idea that the Native New World shaped Early North America (Witgen 2012: 113-5). In this sense, we assume the risk of using the expression “empire” in this article because we understand that, if used critically, it can help us explain the formation of European kingdoms and their expansions, pari passu to the colonization of Americas and parts of Africa and Asia, as Herzog also proposes, from the use of the frontier not as a limit, but as a fluid territory, meaning zones of interactions and conflicts (Herzog 2015).

As an object of study, therefore, we cannot look at the period of the union of Iberian Crowns, without asking ourselves how it was possible-and if it was really possible-to link spaces so distant and heterogeneous, under the domain of a single sovereign, for sixty years.

The union of Portugal to the dominions of Philip II did not bring only one more kingdom to Spain, but the greatest impediment that a European monarch had inherited until then. After being recognized in Portugal as the legitimate successor of Cardinal D. Henrique, the Portuguese Kingdom and wealth were placed under his scepter. Philip II now reigned throughout the peninsula and in the Atlantic islands - Madeira, Azores and Cape Verde; in the African possessions and trading posts in the Morocco lands - Ceuta, Tanger and Mazagão; on the coast of Guinea - from Arguim (present-day Mauritania) to Sierra Leone; in the Gulf of Guinea - Mina, Island of Príncipe, Ano Bom and Sao Tomé, in addition to Angola and Congo; on the east coast of Africa - Lourenço Marques, Inhambane, Sofala, Quelimane, Sena, Tete, Mozambique and Ethiopia. In the east, the main conquests and trading posts guarded by Philip II were in Arabia, Persia, West India, China, the Malay Archipelago, in the peninsula of Malacca, Sumatra, Moluccas and Indonesia. Brazil, added to his dominions, constituted the missing continental portion for Philip II to be the sole sovereign from southwestern North America to the end of South American. (Stella 2000: 16)8

In this sense, in the pages and lines that follow, we will try to show how this colonial administration was constituted in both Portuguese and Spanish kingdoms pertaining to this specific border region in Río de la Plata and Paraguay.

In a paradigmatic book on the relations between Portuguese America and the Río de la Plata, Alice Canabrava (1984) established the initial decades of the Iberian Union as the period of the opening of Buenos Aires to the Atlantic route. This happened between 1580 and 1618 and was emblematic of this prominence, due to the asiento system, by which the Spanish Crown authorized the Portuguese to trade enslaved Africans coming from Luanda and landing in Buenos Aires. It was also in that same year that the province of Río de la Plata was created in recognition of the importance that the region had in the geopolitics of Spanish dominions in America. However, Canabrava also states that within a short time there would be a reversal of this advantageous situation for the Plata region. While the end of Spain’s peace with the United Provinces led the Spanish empire to take more control of its borders to prevent attacks on its dominions, the creation of the customs post in Córdoba (1623) indicated that the highest economic transactions were carried out in the province of Tucumán and not in the province of Río de la Plata (Gadelha 1980: 164-165).

At this point, it is up to us to try to understand, after all, what the Iberian Union meant and the consequences it brought for the region studied. In recent decades, in their examination of the theme of the union of the Iberian Crowns, historians specializing in the Iberian world have avoided the risks of a nationalist vision that projects on the past of the Portuguese metropolis an anachronistic vision of identity in relation to the political repertoire of the kingdoms of the modern era (Schaub 2001: 29). The disputes between the dynasties were based on other mechanisms, which used the power of the armies and authorities that acted in the name of the king to establish control over distant territories, subjecting different peoples and continents to the interests of a certain kingdom. Thus, the search for a Portuguese identity that could give cohesion to this multifaceted whole makes more sense within the nationalist political and identity disputes that emerged among the countries that became national states in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Although the discourse about valuing a “Portuguese spirit” may have fueled the rhetoric of the final years of the Iberian Union, demarcating the restoration of the Portuguese throne by the Bragança dynasty, this movement has to be seen within the dynastic conflicts of the modern era and the wars for the domination of the “four parts of the world,” to use an expression made famous in a recent book by Serge Gruzinski (2014).

In this line of analysis, Bouza’s work shows how the idea of the Iberian Union was instrumentalized in different rhetorical and political senses. Analyzing the image of Lisbon, the author shows that for a time, an image of the city was cultivated as a widow supported by the Spanish monarch and, later, on the contrary, that the court needed to free itself from the power of a tyrant (Bouza 1993). In turn, during the Portuguese independence movements to leave this alliance, the discourse was inverted, resuming the idea that it would be only through Portuguese autonomy-which would take place under the Bragança throne-that the destiny of Portugal as the great nation chosen by the Christian god would be fulfilled (Lima 2010).

In any case, the arrangements that sealed the fate of the Portuguese kingdom under the aegis of King Philip II of Spain (Philip I of Portugal), made in 1581 in the city of Tomar, maintained the administrative autonomy of the Portuguese kingdom in practice, despite the formal submission of Portuguese subjects to Spanish power, preserving the institutions and order of the Portuguese Empire. When we look at the frontiers between the dominions of the two empires, we cannot speak of Spanish annexations or incorporation of parts under Portuguese domination in the Americas. In any case, some authors have proposed the idea that during the period of the Iberian Union, there was a modernization of Portuguese administrative structures, influenced by the Spanish legal apparatus. This hypothesis was defended by António Manuel Hespanha (1989: 58), who formulated the idea that the synodial, natural law model adopted by Portugal, which resulted in a headless and decentralized empire, was consolidated precisely as an inheritance of the Spanish model. Deriving from this line of analysis, Guida Marques (2002) specifically analyzed the changes that took place in Brazil during the period of the Union. In general, she highlighted the foundation of numerous forts in different parts of Portuguese America, in addition to the conquest of Maranhão, as an effort to control and consolidate Portuguese colonization in American territory. On the other hand, Marques also believed, trying to adjust the data to the model proposed by Hespanha, that the Iberian Union represented a model of greater autonomy for Brazil regarding the powers of governors and captains in the face of royal power (Marques 2002).

In a more recent study, Stuart Schwartz (2008) worked with economic data from Iberian imperial expansion in the first decades of the seventeenth century and the disputes between the other European kingdoms over the colonial territories and seas. According to him, the search for the control of colonial wealth, such as the silver of Peru, is what led to the agreement for the union of the Iberian monarchies (Schwartz 2008). In this sense, the attempts to unite the common interests of the two empires had their contradictions, testing the limits of how long this junction could last (Valadares 1993). In this way, perhaps it is precisely in local conflicts, based on the realities of each of the parties that made up the imperial whole, that we can find answers to what worked and what was not implemented during the Iberian Union.

In a study written a few decades ago, Henriquete Vila Vilar (1973) established very impressive data on the conflicts and interests involving the Portuguese and Spanish in the Plata region and in the transatlantic trade. It is possible to see the construction of the Portuguese monopoly from the numbers taken from the Casa de la Contratación, a commercial supervisory body, strategically located in Seville. Thus, the asiento regime allowed the Portuguese to achieve a prominent position in the slave trade in Spanish America, as previously seen. Thus, between 1595 and 1615, 505 slave ships were registered, 263 from Lisbon, 47 from Spanish ports, and 195 without identification (Vila Vilar 1973: 563). From this analysis, the author demonstrated there was an evident incentive, on the part of the Spanish Crown, for the circulation and permanence of Portuguese in their dominions, as well as trade negotiations. This was also a point of conflict with Castilian subjects, who complained to the king that the Portuguese had too many privileges and spaces in the mercantile sphere, which led to the belief, among Castilians, that the Indies of Castile belonged to the Portuguese. (Vila Vilar 1973: 574). Based on this discussion, it is now up to us to examine a little more the attempts at connections between the Spanish and Portuguese worlds in this region of open and fluid frontiers during this period.

Walking Through Internal Routes

Studies carried out in recent decades have tended to increase the role of the vila of São Paulo in the first two centuries of the colonization of America. Rafael Ruiz’s (2002) work, for example, goes so far as to state that São Paulo became the gateway to the Spanish Empire in the period of the Iberian Union. José Carlos Vilardaga’s (2010) work aimed to escape the risk of this over-dimensioning, warning that many events involving the vila during the union were obviously restricted to the local sphere. Nonetheless, for this author, São Paulo did play a paradigmatic role in this context, since it was located in the final settlement before the frontiers with the Spanish territory. This made it a privileged locus for understanding exchanges between different agents, interests, and cultures related to it (Vilardaga 2010: 82). We agree with this line of analysis, also reflecting on how much this frontier condition involving Asunción, Guairá, and São Paulo allows us to perceive the conflicts and the convergences between two imperial expansion projects (Sposito 2012). The question that we must answer is whether the fact that both crowns were united in this period meant a change in tensions in the Plata-Paraguayan region, since access and connections were permitted. Before proposing some answers to this question, it is advisable to examine what occurred in this period in more detail.

The governor-general of Brazil between 1591 and 1601, D. Francisco de Souza, was an important figure in the search for increased colonization in the southern parts of the colony. Precisely because he was so focused on the potential of exploring other parts of the territory, he was appointed again a few years later as governor, but this time restricted to the so-called Southern Repartition (“Repartição do Sul”), in a proposal for the colony’s administrative division between 1607 and 1611. The search for precious metals became a kind of obsession for him. In an extreme act, he tried to transform the vila of São Paulo into “another Peru,” as analyzed by Sérgio Buarque de Holanda (2000). In this episode, Souza even ordered the importation of llamas, animals that are important for cargo and wool, typical of the Andean environment, believing that they would also acclimatize in the vila, since it had a milder climate in relation to other parts of Portuguese America (Holanda 2000: 114). In any case, despite the gold found in the Pico do Jaraguá region (in the current city of São Paulo) and in the Paranaguá mines (in the current state of Paraná), this did not generate significant gold production in the captaincy of São Vicente, nor mobilized the crown’s greater efforts to invest in this exploration. The desire to seek and exploit mineral wealth was considerably reduced after Francisco de Souza’s death in 1611.

Another movement that involved countless elements that illuminate the connections along the frontiers between the Empires was the arrival of Jesuits in Paraguay in 1587. The voyage that made this venture possible involved a plan composed of countless kinship and business relationships connecting the Atlantic world. Francisco de Vitória, Bishop of Tucumán, sent a ship to Salvador, which was supposed to bring European Jesuit priests and some products to a mission in Paraguay. The vessel left the Brazilian capital with numerous products, also loading food and other supplies during stops in the ports of Espírito Santo, Santos, and Rio de Janeiro. In the end, the ship was looted by pirates at the entrance to the Río de la Plata and was shipwrecked, losing the immense cargo of silver and African slaves that was being smuggled along that route.9

In addition to these economic injunctions, which demonstrate the role of Buenos Aires as a route for legal and illegal commerce, the voyage was also the starting point of the Jesuit presence in Paraguay and Río de la Plata. This would be very strong in the following decades until the expulsion of the Society of Jesus from Portuguese and Spanish territories in 1759 and 1767, respectively. This marked the beginning of the construction of the reductive model of indigenous missions, already implemented in other parts of the Portuguese and Spanish Empires. Formulated by Manuel da Nóbrega, the proposal generally consisted of the confinement of indigenous allies in communities controlled by missionary priests, who were to convert their souls while instructing them in the civil ways. Based on the model of itinerant missionaries practiced by the priests of the recently founded Society of Jesus, Nóbrega defended the creation of a model that would subject indigenous bodies to disciplined work and Portuguese laws, a moment in which the indigenous people would truly convert to the Christian faith. With this proposal, the aim was to control and “compensate” allied indigenous groups, while attacks were launched against those who still opposed the Portuguese presence in American territory (Nóbrega 2000). It is important to highlight that while these proposals were conceived and began to be implemented in Portuguese America, it was in Spanish territory where they reached their greatest development, with the so-called 30 Povos das Missões [30 Peoples of the Missions]. These were reductions that spread between the Serra do Tape and Uruguay, beginning in the first decades of the seventeenth century and expanding until the expulsion of priests in the mid-eighteenth century.

Here we come to a point in which several elements mentioned throughout the article converge, that is the role of Jesuits in the colonial projects of Portugal and Spain and, more specifically, in the colonization of the frontiers of the Spanish dominions of southern America. As outlined in Image 3, the missionary areas in Guairá, Itatim, and Tape-Uruguay, which are surrounded by a white line on the map in question, started to function as a spearhead of Spanish occupation. While being a frontier is naturally a condition of tensions and attacks, there were also a series of problems internal to the missions and in relation to the other Spanish actors that transformed the missions into a kind of powder keg. The conversion process itself meant entering territories of people hostile to Christians to obtain new catechumens, while at the same time there were tensions between priests and converts for the adoption of new practices (Eisenberg 2000). Moreover, there were disputes between the missionary universe and the outside world, since the indigenous people were disputed on both sides of the border, both by Spanish and Portuguese, not with the aim of converting them, but as “pieces” who the colonizers wanted to enslave.

The actions of two governors of Paraguay and the ways they dealt with indigenous peoples and Jesuits evidence different perspectives and actions. In 1604, Governor Hernan Arias de Saavedra (also called Hernandarias) had an extremely positive view regarding the strengthening of relations between São Paulo and Asunción, asking that roads between the two parties be frankly encouraged, to develop the region.10 A little more than a decade later, Hernandarias’s position in this regard was diametrically opposed: after the constant attacks of sertanistas on Paraguayan territory, the governor was fully aware that bandeirante action would cause depopulation in the region due to the trafficking of indigenous people to the captaincy of São Vicente.11 It is also worth mentioning that Hernandarias was an enthusiast for Jesuit missions, believing that the reductive model was a project that was perfectly suited to royal interests.

In 1628, the scenario changed with the arrival of another governor in Paraguay. Unlike Hernandarias, who was the first Creole (of Spanish descent but born in the America) governor of Paraguay, Luis de Céspedes Xeria came from Spain to assume the position to which he was appointed. Like many other figures of the period, Céspedes Xeria’s relations were not limited to contact with the Paraguayan and Plata regions. To the contrary, the new governor visited several cities in Portuguese America, marrying a member of the powerful Sá e Benevides family in Rio de Janeiro. He passed through the vila of São Paulo and from there he went to Paraguay by a path that was prohibited at that time. When making contact with the sertanistas, the newly appointed governor of Paraguay brought news about the expectation of destruction in the region. Arriving at Guairá even before taking office in Asunción, Céspedes Xeria warned that the Paulistas, accompanied by their Tupi troops, were coming to attack the Jesuit missions. Instead of defending them from these attacks, the governor endorsed the criticisms made by the residents of the vilas of Ciudad Real del Guairá and Vila Rica del Espírito Santo and even the sertanistas themselves: that the Jesuits sheltered indigenous people in their missions that belonged to Spanish and Portuguese and therefore these missions would be attacked.12

In fact, the largest bandeira ever carried out was precisely the one that the governor referred to, which some believed consisted of 800 Portuguese and about 2,000 indigenous people. Commanded by Raposo Tavares, the sertanistas arrived in the missionary region at the end of 1628 and in the following months the wars against the reductions began. In all the comings and goings between São Paulo and Guairá, this resulted in the enslavement of 60,000 indigenous people over two years, as mentioned before. This process led to the abandonment of the Guairá region by the Spanish and the displacement of the missions to a more southern part of the territory, precisely on the borders between the Plata and Paraguayan provinces, in Tape and Uruguay. In any case, Céspedes Xeria’s controversial performance did not pass unscathed. Shortly after arriving in Paraguay and the beginning of the bandeirante offensive against the missions, having barely taken office, the governor had to answer the charges of having followed the prohibited route from São Vicente to Paraguay by land, of having brought contraband on this travel, and of not preventing the sertanistas from using the same path. As a result of this imbroglio, Céspedes Xeria was removed from office.13

Another issue surrounded by controversy is the role of Portuguese colonial authorities in combating bandeirante actions. The vila of São Paulo, as well as the State of Maranhão, were both considered “rochelas,” points of resistance to royal orders, for disobeying the laws of the kingdom by enslaving indigenous people, who could only be made captive through just wars14 (Alencastro 2000; Monteiro 2002: 60-61).

The law of indigenous freedom in colonial Brazil, which came into force in 1570, in addition to theoretically ensuring the welfare of the natives, was a way for the crown to control access to this workforce. In other words, as of this date and according to a series of other measures adopted during most of the colonial period, indigenous people could only be enslaved through wars enacted according to justifications, whereby they were considered as legitimate. In addition, requests for wars against a certain indigenous group or aldeias had to be authorized by a just authority, with a high position, such as a governor- or captain-general, or according to the king’s own decree (Thomas 1982: 221-222).15 When the Paulistas left, at their own risk, to hunt indigenous people to enslave on their lands, they violated royal laws and were at the same time traffickers and masters of indigenous enslaved. There were innumerable moments when “ouvidores,” governors, or bishops tried to punish Paulistas for these deeds. However, the authorities were invariably challenged and disobeyed by the residents of the captaincy of São Vicente. This happened through uprisings, threats to the lives of their opponents and, in extreme cases, their expulsion from the captaincy, as happened to the Jesuits, who were banned from the São Vicente captaincy villages between 1640 and 1654 (Feitler 2013).16

What we want to demonstrate here is that, both in Paraguay-Río de la Plata and in the captaincy of São Vicente, there were different approaches, at distinct times, by diverse figures to propose alternatives forms of relationship between the Portuguese of São Vicente, the Spanish of the Río de la Plata and Paraguay, the Jesuits, and the indigenous people. In this sense, the Iberian Union period meant the aggravation of tensions that were already in place. While at the beginning of the Iberian Union there was in fact an incentive to the opening of routes between São Vicente and Paraguay, both on the part of the crown and of some governors and other authorities, this reality changed completely in the 1610s. In the face of the Dutch offensive against the Iberian dominions, which in the following decades involved numerous Dutch invasions, in addition to disputes over American territories with Britain and France, the Spanish Crown began to better control borders and veto access to ports (Marques 2013). In this sense, the bandeirante invasions in Paraguay and Río de la Plata did exactly the opposite: when the transit between the Empires was prohibited, the bandeirante activities grew most.

This leads us to the point that even though the Iberian Union serves as a guide for us to be able to understand the dynamics of colonization and issues related to the residents of São Paulo, Paraguay, and Río de la Plata, it does not help us understand the explosion of bandeiras in this period. Thus, the greater circulation of Paulistas in Guairá during the Iberian Union was due to internal causes.

A number of factors developed in each part of southern America between the late sixteenth and the early decades of the seventeenth centuries. On the one hand, in 1585, the residents of the captaincy of São Vicente systematically began to enter the sertão of the captaincy, with the justification that they had to fight against attacks by the “Carijó.”17 In fact, as was evident from the justifications later given by the Paulistas, and from the way they dealt with indigenous populations, this activity was driven by the search for labor that would support the Paulista economy and society. At the same time, as demonstrated earlier, the Guarani of Paraguay were already coveted by the Portuguese, which can be attested by the previously mentioned 1557 citation from the Jesuit Nóbrega.18

Rather than the Iberian Union, the element that connected the extremes of the two Empires in this period were the Guarani. From this observation, it becomes clear that the advance and retreat of the bandeirantes over the Plata and Paraguayan regions has internal responses, which must be found precisely in the role played by the missions founded by the Jesuits, especially among the Guarani peoples. Thus, it was in the 1610s, through the visitor Francisco de Alfaro at the behest of the Real Audiencia de Charcas (Viana 1971: 475-481), as well as the activities of the previously mentioned governor of Paraguay Hernandarias, that the Jesuit presence began to constitute a project of the local administration to develop the region, supported by the crown.

In 1609, the first missions began to be founded in Guairá and their growth in the following decades would only be stopped by the bandeirante threat, which destroyed towns and missions. This led to a shift in Spanish colonization to Tape and Uruguay, following the territories on the right bank of the Uruguay River. From the 1630s onwards, the growth of the missionary population, as well as their counteroffensive, authorized to carry firearms, would generate a reflux of bandeirante expeditions in Spanish parts. This became more effective after the great military defeat that the sertanistas suffered in Mboboré in 1641.19

In addition, the redirection of the Paulistas by the colonial authorities to other activities in the following decades showed that Sertanista expertise could be used for other purposes. Thus, between 1650 and 1670, the bandeirantes came to the northeastern region of Brazil with the objective of overthrowing the Quilombo dos Palmares and capturing indigenous people from the interior, who clashed with colonizers in their lands, and their livestock.20 At the end of the 1670s, the Portuguese Crown also recruited Paulistas and their indigenous troops to follow the traces of emeralds and other precious stones in what came to be the region of Minas Gerais. Finally, also in the same period, the bandeirantes were recruited for an expedition of military conquest, with the intention of founding Colonia del Sacramento on the right bank of the Plata River, in front of Buenos Aires. However, all these steps differed greatly from the bandeirante actions in their origin. But these are chapters of other stories, which we will not be able to tell here.

Conclusion

In this article, we have sought to follow some digressions that help to think about the relations between the imperial projects, through the union of the Iberian Crowns, and their implications at a local scale, in a border region in a distant area in their American dominions. After analyzing countless factors about the realities of each location, getting to know a little about the actors involved in this process and the causes that moved them, we plunged into an area of constant tensions and disputes. On the one hand, we focused on the political arrangements of European dynasties which culminated in the Iberian Union under the Habsburg throne during the Philippine period. On the other hand, despite briefly discussing the possible political and administrative changes in the Portuguese Empire, we perceived a moment of opening of routes between Portuguese America and the Plata region. However, contrary to what it might seem, at the peak of the bandeiras advances into Spanish areas, this route was prohibited. This indicates that there was no official project by any of the crowns for the Portuguese to take possession of the sertões of the provinces of Paraguay and the Río de la Plata at that time. Before that, we realized that while the agreements between the crowns meant a period of respite from the disputes between the Empires, the same cannot be said in relation to the frontiers analyzed here.

In this scenario, Jesuits and Guarani ended up becoming spearheads in advancing and defending Spanish interests within the territory. In spite of all resistance to the authorization of the carrying of arms by indigenous people, after an arduous embassy of priests to Rome and the king of Spain, permission was obtained, accompanied by the supply of weapons and ammunition for the missions. From then on, missionary soldiers managed to turn the war they were waging against the bandeirantes in their favor.

For this reason, it is important not to look at Guairá just as an exceptional territory, but as yet another colonial space where wars of conquest and colonization of the continent took place. Herzog has argued that it is necessary to see how both dimensions are related in frontier spaces: “how the theoretical division coined in 1297 was implemented or how early modern individuals living in both Spain and Portugal and their communities understood, built, and defended their right to land, thus also contributing to the formation of the border” (Herzog 2015: 5). There, the interests of indigenous people, residents, and Jesuits were confronted by the presence of Portuguese invaders, who forced all other actors to react to their pillage. Finally, we must reflect if it was the Society of Jesus that tried to mobilize institutions and authorities to face the bandeirantes, covering São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Lisbon, Madrid, and Rome. As a religious order that had branches and agents in these spaces and in many other areas around the globe, the Society of Jesus, in reaction to the destruction of Guairá, dispatched embassies to ecclesiastical and temporal authorities in Europe and generated riots in the city of Rio de Janeiro and in the captaincy of São Vicente-from where they ended up being banned (Feitler 2013). With the data presented, it does not seem correct to believe that arrangements between the metropoles were behind the emergence, increase, and combat of bandeirante actions.

I end this article by evoking the comments received on this research when it was presented in a seminar.21 Reflecting together with my colleagues on the key question posed here, about how the center of metropolitan power tied itself to the peripheries of the Atlantic world, one can, in fact, think of the Iberian Empires precisely as the connection between several peripheries, which were not only in the distant Río de la Plata and the Guairá, but in Europe itself. This connects with what Guida Marques (2013: 249) said: “It also forces us to leave the Eurocentric view, explaining the colonial dynamics only by the impulses of the metropolis, and to link the internal dynamics of colonization and the imperial dynamics in another way.” Borrowing the way Herzog beautifully ends his work, when we look at the experiences of Portugal, Spain, Britain, and other European kingdoms, we can see how each of them manipulated the discourse on the presence of Native Americans, and how Europeans would usurp their territories and justify their presence in the Americas. Thus, from wars and alliances with indigenous peoples, they shape the European occupation of America and their discourses on imperium and dominium (Herzog 2015: 257-259).

I would dare say that, in the case of Guairá, the crowns only acted against the Portuguese-if they did so-when convinced by the Jesuits that they should punish the São Paulo attacks. This does not mean to say that the bandeirante actions were against the crown’s purposes, having seen how the same Paulistas, also considered rebels and intractable, were later mobilized for various activities, recruited by governors and captains. Such was the case with the founding of Colonia del Sacramento in 1680.22 However, the disputes in Sacramento, unlike Guairá, were clearly a Portuguese imperial project for the Plata estuary, a process that would unfold in the border conflicts of the 18th century (Prado 2015; Quarleri 2009; Garcia 2012), which is beyond the scope of this article.