The COVID-19 pandemic has had an important negative impact on individuals, societies, and countries (Alizadeh et al., 2023). Given the easy spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, several preventive measures have been recommended by the World Health Organization [WHO] and national health agencies, at the (inter)national and individual levels (WHO, 2020). These include, at an individual level, the recommendation of using masks, physical distancing, and avoiding large gatherings (WHO, 2020). At a macro level, national governments and health authorities introduced public policies directed at controlling the spread of SARS-CoV-2, including mandatory telework, school closures, and prohibition of mass gatherings (WHO, 2020). The efficacy of such measures, however, is highly dependent on the individuals’ adherence (Alvarez-Galvez et al., 2023; Georgieva et al., 2021; Levitt et al., 2022; Mækelæ et al., 2020), which is known to be predicted by several personal (e.g., perceived personal risk, past adherence to public health policies) and social (e.g., social norms) factors, as well as by the clarity of the (inter)national authorities’ communication about the virus, and the confidence/distrust in these authorities ability to take measures that are appropriate to effectively tackle the pandemic and mitigate its spread and impact (Alvarez-Galvez et al., 2023; Georgieva et al., 2021; Levitt et al., 2022; Quinn et al., 2013). Considering this, and since an important predictor of future behavior (e.g., adherence to public health policies in future public health crises) is past behavior in similar circumstances, knowing how citizens perceived the governmental management of the COVID-19 pandemic might be useful to uncover the possible underlying causes of pandemic management's (un)success and to adequate plan for upcoming health crises.

For instance, one study with 9543 respondents from 11 countries uncovered that adults showed higher levels of adherence to governmental and health agencies physical distancing measures when they perceived such measures as less restrictive and more effective in preventing the dissemination of COVID-19 (Georgieva et al., 2021). Other studies with samples from Brazil, Colombia, Germany, India, Israel, Norway, and the USA concluded that satisfaction with one’s government may also positively influence the perceived government effectiveness and, consequently, benefit adherence to public health guidelines and decrease the levels of worry and fear of COVID-19 (Mækelæ et al., 2020; Thaker et al., 2018). On the other hand, low trust in the government, combined with extreme government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, may result in lower adherence (Georgieva et al., 2021).

Based on previous literature, it appears that to successfully fight public health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, citizens must adhere to the recommended health measures. This can be accomplished if individuals, on the one hand, perceive the measures as effective and not too restrictive and, on the other hand, trust the government and perceive its communication as clear. There is, however, a lack of information concerning the shortcomings of government management and how they might be addressed. This knowledge facilitates a better understanding of public health crisis management, which can aid in making informed decisions about what may need to be changed and how best to achieve these changes. In the case of public health campaigns, for instance, qualitative data can be used to determine the success or failure of the campaign by providing an understanding of why and how individuals chose to adhere to such campaigns (Verhoef & Casebeer, 1997). By focusing on the meanings, experiences, and perspectives of all participants, qualitative research allows a deeper understanding of phenomena in the natural world, that cannot be obtained through quantitative methodologies (Verhoef & Casebeer, 1997). To our knowledge, no previous qualitative study has researched, in-depth, laypersons’ views on the adequacy of public health policies adopted by national governments and health authorities to tackle the pandemic. Hence, this study aimed at exploring these issues.

Method

Participants

Participants included in this cross-sectional observational study were adults from the general population who were living in Portugal from March to May 2021, from a non-probabilistic convenience sample. Inclusion criteria were: (a) residing in Portugal between March 2020 and May 2021; (b) minimum age of 18 years old; (c) being able to understand Portuguese; and (d) consent to voluntarily participate in the study. A total of 93 participants agreed to participate. However, two participants were excluded due to technical issues with the recording, and three participants were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criterion (a). A total of 88 adults were included in the analysis (women: n = 45; 51%), with ages varying between 19 and 92 years old (M = 50.4; SD = 18.9).

Participants were mainly married (n = 39; 44%), followed by single (n = 35; 40%), widowed (n = 8; 9%), and divorced (n = 6; 7%). Almost all individuals were working, either part-time or full-time (n = 57; 65%), while the remaining sample was either retired (n = 20; 23%), studying (n = 6; 7%), unemployed (n = 4; 4%), or working and studying simultaneously (n = 1; 1%). Regarding their region of residence during lockdowns, most individuals (n = 80; 91%) spent both lockdowns in the same region: 35 (40%) in the northern Portugal, 17 (21%) in the Metropolitan Area of Lisbon (MAL), 15 (17%) in the southern Portugal, and 13 (15%) in the Portuguese islands. However, eight participants (9%) spent the lockdowns in different regions of residency.

Materials

A sociodemographic questionnaire (e.g., age, gender) and a semi-structured interview script were developed. Relative to the aim of this study, participants were asked to share their opinion about governmental management in Portugal: “During the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been a series of measures enacted by the government to mitigate the spread of the SARS-Cov-2. What are your views about these measures?”.

Procedure

Prospective participants were invited via social media (e.g., Instagram), email/cold calls to organizations (e.g., city council), or participation in previous studies conducted by the research team. The study has been approved by Ispa’s Ethical Review Board for Research (reference I/033/04/2020). Prospective participants were contacted via email or phone to schedule an online (n = 83; 94%) or in-person (n = 5; 6%) interview, depending on their preference. Interviews were conducted by the first author between January and September 2022. Participants were debriefed about the study’s aims and procedures, its voluntary and anonymous nature, and written informed consent was obtained, before the beginning of the interview. Interviews were audio/video-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

Codebook inductive Thematic Analysis (TA; Braun & Clarke, 2022) was performed, with themes and subthemes being identified based on raw data, within a critical realist/contextualist paradigm. First, the first author read, analyzed, and open-coded 15 interviews, which served to create the codebook of potential themes and subthemes. Next, the same author coded the remaining interviews according to the generated codebook, although with freedom for adjustments. The generated codes, subthemes, and themes were interactively discussed with the second and fourth authors.

Results

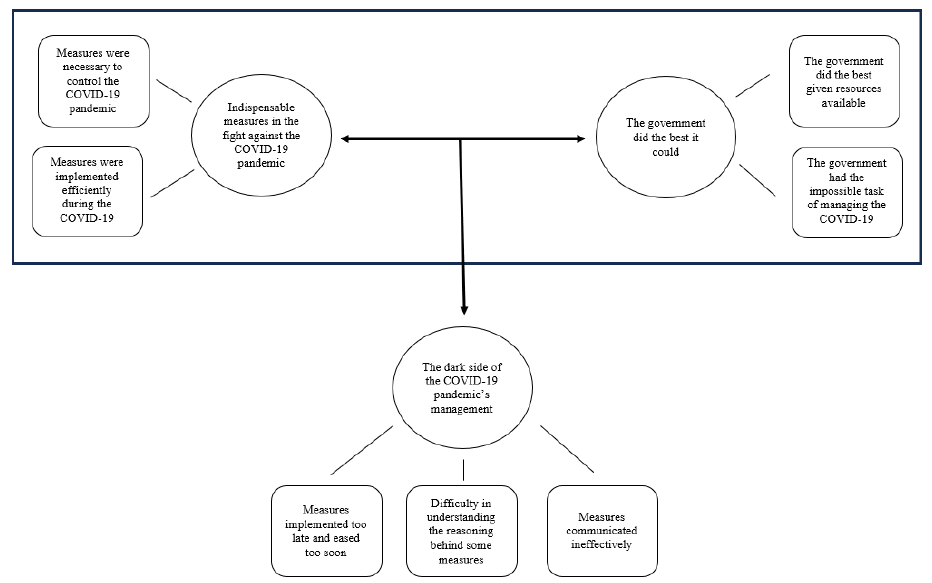

Three main themes were identified regarding participants’ views about the way Portuguese governmental and health authorities managed the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 1): (a) Indispensable measures in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic; (b) The government did the best it could; and (c) The dark side of the COVID-19 pandemic’s management. Almost the entire sample believed that implementing measures was crucial to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus and avoid harsher consequences, and that governmental entities used the available resources to make the most of the situation. However, participants also believed that there were some negative features during the management of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Indispensable Measures in the Fight Against the COVID-19 Pandemic

The first theme included beliefs about the necessity, relevance, and effectiveness of the measures implemented by the government in Portugal and included two subthemes: 1) Measures were necessary to control the COVID-19 pandemic; and 2) Measures were implemented efficiently during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly all participants (n = 74; 84%) recognized the implementation of measures as necessary and key in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the efficacy of the Portuguese government during this time of crisis.

Regarding the first subtheme, almost all adults (n = 67; 76%) agreed with most of the implemented measures, such as “mask, social distancing, respiratory hygiene, hand washing” (Carolina, 25 years, MAL). These measures, although uncomfortable and wearying (e.g., wearing a mask for a long period, disinfecting hands several times a day), made participants “feeling safer when [..] [leaving] home” (Susana, 43 years, northern region). Of the imposed measures, participants highlighted the lockdowns as maybe the most essential measure in containing the pandemic, even when personal well-being was jeopardized, as undoubtedly explained by Isabel (26 years, MAL):

Well, hum...When the aim is to safeguard the population, hum, I consider it something very positive, right? […] So, yeah, even though for me it was very difficult to be confined […], a lot of stress, […] depressive symptoms […], it was very, very complicated, hum, but even though it was painful for me, hum, it was also positive because I knew that the lockdown was the way to safeguard the entire population.

Although participants recognized some measures as “more drastic, […] it had to be so at the beginning […] [since there was] a huge lack of knowledge among the entire scientific community and a lot of doubts about the situation” (João, 68 years, northern region). The lack of information, the novelty of the situation, and the uncertainty around it contributed to the apparent acceptance of stricter measures as necessary and, possibly, to the adherence to preventing behaviors recommended by the government and health agencies, such as the ones mentioned above.

Figure 1 Thematic map depicting the themes and subthemes of adults’ perceptions about the governmental management of the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal

Some individuals (n = 31; 35%) also discussed how the measures were implemented efficiently during the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal (subtheme 2). The implementation of measures between 2020 and 2022 was considered well-organized, well-applied, and adjusted to the situation, even with the negative socioeconomic consequences arising from them. According to participants, the Portuguese government showed overall good public health crisis management skills not only by initially implementing more restrictive measures, such as the lockdown but also by reducing restrictions when people needed greater freedom of movement. In fact, this shift overtime allowed the participants to feel simultaneously protected against the COVID-19 disease and mental health deterioration by providing a sense of security, comfort, and normalcy. As explained by Magda (32 years, MAL and island region):

“Portugal was one of the examples out there and I know [the lockdowns were] a big nuisance and there were a lot of economic activities that suffered a lot and that's bad. But at the same time […] we managed to have good measures here [in Portugal], we have a good […] level of vaccination and that's why I think we [could get out of the lockdown] […] I thought the measures were balanced because [the government] also started to give us some freedom, ok, proposing [COVID-19] tests. It was necessary to be tested, or […] have [vaccination] certificates, but at least it was a way to get back to normal.”

Further, during the COVID-19 pandemic, but especially at its beginning when information was scarce and the level of fear was high, the governmental entities and health agencies responsible for managing the pandemic showed great concern in “explaining to people what was happening, […] which measures were going to be taken, always remembering that […] we were on experimental ground, and that these measures could be reversed and changed. […] That left me feeling at ease.” (Carla, 49 years, MAL). This transparency may have contributed to a sense of safety and trust, whilst buffering any animosity or frustration that could arise from sudden changes in the implemented measures.

The Government Did the Best it Could

The second theme concerned participants’ views on how the COVID-19 pandemic was managed in Portugal within the limitation of the available resources (e.g., financial, informational). This theme was subdivided into two subthemes: 1) The government did the best given resources available; and 2) The government had the impossible task of managing the COVID-19 pandemic. Half of the sample (50%) spoke about the challenges that government officials (e.g., Prime Minister, Minister of Health) had to face during times of health crisis, especially during the biggest worldwide crisis of the 21st century, with limited information on the topic and restricted resources available to the country.

The quality of the management of the COVID-19 pandemic by the Portuguese government was limited by the information and resources available at the time of the pandemic (subtheme 1), as some participants described (n = 35; 40%). For example, at the onset of the pandemic, several measures were implemented based on the limited information about the virus and its prevention. However, due to the novelty of this health crisis, errors and setbacks were to be expected, as clarified by André (58 years, southern region):

“Maybe now looking back, some measures were unnecessary, but this was a path that no one knew, right? […] It was the first time that we had a, a health system and a government that had to try to control things and so, in fact, they were also experimenting, right?”

During the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government often changed the measures in place. Although these changes may have complicated “a little the dynamics of society and the plans that we define and draw up can sometimes be conditioned by this circumstance” (Catarina, 36 years, northern region)", participants acknowledge “that these […] changes […] are perfectly justifiable with... The evolution of the situation... With the knowledge that health authorities had of the disease” (Custódio, 46 years, MAL). Further, adults in Portugal also discussed how the government acted in the best interest of its population, thus implementing strict or harsh measures only when utterly necessary. As exemplified by Joaquim (71 years, southern region):

“[…] In my point of view, they [our governors] did what, at each moment and with the means available, and considering the conditions that existed, I think they did what was indispensable and what was most favorable to responding to this […] pandemic situation that we lived.”

Apart from the government doing the best given the resources available, a few individuals (n = 20; 23%) also described the task of managing a pandemic as an impossible task (subtheme 2). Indeed, participants confess that “it wasn't an easy task either […] for the DGS [Directorate-General of Health of Portugal] or for the government” (Anibal, 44 years, MAL and southern region) to suddenly having to respond to a new emergent health crisis, based on little information, sometimes even contradictory. One health crisis that no one was prepared for. Given this scenario of uncertainty and insecurity, some adults felt that the best solution for their well-being was to put their trust in the government and responsible health entities, as demonstrated by Cidália (46 years, MAL):

“We must trust the guidance of […] those who decide, right? Which is, hum, mainly supported by technical information […] We essentially must trust [the government], because otherwise we often live in constant shock and, and the constant doubts would eat us up inside. […] [Thus] I think it's easier […] to trust, accept, and hope that it works [laughs].”

The Dark Side of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Management

The third theme encompassed negative features regarding the management of the COVID-19 pandemic by governmental and health entities, including what measures participants felt as not working and that could have been improved. Three subthemes were identified: 1) Difficulty in understanding the reasoning behind some measures; 2) Measures implemented too late and eased too soon; and 3) Measures communicated ineffectively. Many participants (n = 59; 67%) discussed how the reasoning behind the implementation of some measures was difficult to understand, the timing of the implementation of some measures was off-timing, and communication was somewhat confusing and unclear.

Around half of the sample (n = 46; 52%) confess to having some difficulties in comprehending the reasoning behind the implementation of some measures, or even believing that some measures were excessively harsh (subtheme 1). Indeed, some individuals firmly believed that “some [measures were] not justifiable, even […] counterproductive” (Francisco, 28 years, northern region). For instance, during 2020 and 2021, reduced opening hours were forced in several establishments, such as supermarkets, restaurants, and bars. Hence, “these measures ended up... funneling everyone into the same schedules” (Ricardo, 30 years, northern region), possibly increasing the chances of contracting the virus and worsening the pandemic situation. Moreover, participants also appeared to be “a bit confused” (Carlos, 83 years, MAL) by the government’s choice of maintaining large food establishments open while closing small ones, since the chances of contracting COVID-19 are bigger in places with larger gatherings of people. Another measure criticized was the mandatory COVID-19 self-tests to enter certain public places (e.g., restaurants, theatres). The main issue was the fact that self-tests “can be manipulated by us” (Beatriz, 25 years, MAL and northern region), can be done incorrectly, and can lead to a sense of “false security […] [because] self-tests have a reliability which is not 100%” (Beatriz, 25 years, MAL and northern region).

This difficulty in understanding the reasoning behind some measures, as well as the government's lack of transparency in attempting to clarify their reasoning during the process of decision-making, may have led to negative consequences for the population. For example, individuals may have had greater difficulty accepting the measures and complying with them, thus feeling frustrated and angry, or even questioning the government's concern for their well-being. As detailed by Ana (30 years, northern region):

“I had times when I was deeply frustrated, irritated by various measures. Which in fact conditioned everyone's lives and began to condition my life. […] There were times when I thought they [the government] were exaggerating. […] I thought the measures were disproportionate, that is... They were high-cost measures, the cost-benefit […] was very low. […] I'm not saying that the benefit was null, but I think that the social cost was immense to only result in the benefit of a smaller percentage of the number of cases.”

Other adults, mainly younger than 66 years old (n = 22; 25%), spoke about how some crucial measures, such as wearing masks or mandatory lockdowns, were implemented too late or eased too soon (subtheme 2), as explained by Ricardo (30 years, northern region):

“At the time, I thought [the measures] […] came late, they were always long overdue. Why just now? […] Like the masks… […] Of course masks won't prevent everything, but they will help. But later the government said, «no, you have to wear masks». […] And then when […] they lifted the lockdowns it was, for me, also early. […] So, for me, it's not that [the government] implemented bad measures, but I think they always came late.”

This lateness in acting or hurry in lifting some measures made younger and middle-aged adults feel angry, preoccupied, irritated, and even with a feeling that, if precautions had been adopted earlier, more COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths could have been prevented. Furthermore, participants believed that “the government implemented least conservative measures and, [for that], we had some setbacks” (Francisco, 28 years, northern region), especially by the end of 2020. Indeed, participants talked about the government’s fatal error of lifting some restrictive measures at the end of the first year of the pandemic due to Christmas celebrations, since this contributed to the worsening of the pandemic situation in Portugal: “making exceptions for the Christmas weekend […] was bad and led to [a second] lockdown. So, it would have been better [if the government] continued […] as it was, instead of making these exceptions […]” (Augusto, 51 years, northern region).

Lastly, some participants (n = 23; 26%) reflected on how the measures were not effectively communicated (subtheme 3). Individuals - once again, primarily younger than 66 years old - mentioned that the lack of clarity when informing the population about what measures were to be implemented, as well as frequently changing the prevailing measures, generated confusion, fatigue, and increased the levels of fear of COVID-19. As Custódio (46 years, MAL) explains, “the communication of these measures, hum, was not always done in the best way” and the constant change of measures during “a time of uncertainty” (Sara, 40 years, northern region) left adults with doubts about how to act, possibly impairing adherence to public health guidelines. Carlota (27 years, northern region) further adds:

“Sometimes I also think that not everything that comes from their side [the government] is very, very clear. [For instance], […] the last time that [some measures] were announced, initially they said that [the measures] would be [announced on] two dates […]: part of the measures would come out on Wednesday, but the definition of [what are] risk contacts, for example, would only come out on the following Monday. So, when they [the government] deleted the dates, there was confusion… «So, am I a risk contact and I have [to isolate for] seven days, or do I still have [to isolate for] ten until Monday?". Therefore, I think that sometimes they are not super clear, and that sometimes worries people a bit, especially those who are at risk […]”

Discussion

This study aimed to explore adults’ views on COVID-19 pandemic management by governmental and health entities. Overall, study participants agreed with the public health measures undertaken by Portuguese authorities to mitigate the spread of the SARS-Cov-2 and the impact of the pandemic, making the most of the scarce economic and human resources available in the country. Most participants accepted well and reported adhering to the implemented measures and recommendations, perceived as both necessary and effective for controlling the pandemic. However, participants also pointed out the existence of several relevant inconsistencies and errors from these authorities when tackling the pandemic. This is especially true from the perspective of those participants under 66 years old, who pointed out the timing of the implementation of some measures, as well as its communication, difficult to understand.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals were willing to experience some discomfort when adhering to the preventive measures if they were perceived as effective, as evidenced by our results and other studies (Georgieva et al., 2021). Thus, the effectiveness of every measure implemented by governmental and health entities needs to be targeted when developing public health campaigns to increase adherence. Besides discomfort, excessive restrictiveness of the measures was also tolerable at the beginning of the pandemic due to the lack of information globally, uncertainty surrounding the situation, and trust in the government. Literature has shown that a lack of information and higher levels of uncertainty can increase the levels of fear, leading to behavior changes in the short term (i.e., complying with the desired behaviors of governmental and health agencies; Harper et al., 2020). However, caution must be taken when applying restrictive measures, as measures perceived as more restrictive may have lower rates of compliance (Georgieva et al., 2021). In fact, a study conducted in Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, India, Latvia, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and UK (n = 9543) revealed lover levels of compliance to physical distancing measures when they were perceived as more restrictive (Georgieva et al., 2021).

Trust in governmental and health authorities, as well as trusting that the measures taken by them in response to the COVID-19 pandemic are in the best interests of the public, can also result in higher levels of adherence to such measures (Alkhaldi et al., 2021; Costa-Font & Vilaplana-Prieto, 2023). We can hypothesize that the government’s apparent success in influencing the public's acceptance of constant change and measure reformulation was achieved by directly confronting the uncertainty present during the early stages of this health crisis (Quinn et al., 2013). This may have contributed to the public’s awareness and understanding of changing information (Quinn et al., 2013), especially since it was a novel situation. However, trust in and clear communication by governmental and health authorities was not always optimal. This can be problematic since, on one hand, trusting citizens are more easily persuaded of the effectiveness of a given measure (Georgieva et al., 2021), as well as more likely to accept political decisions as valid, although these decisions may harm their interests (e.g., lockdown; Rudolph & Evans, 2005). On the other hand, clear public health communication can influence citizens' perception of government efficiency (Quinn et al., 2013), possibly affecting the evaluation of pandemic management as (un)successful. For instance, a study with a representative sample of the US population (n = 2079) concluded that the quality of the information provided by the president positively affected vaccination acceptance during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic (Quinn et al., 2013). Another study conducted with a large sample (n = 970) in Israel, on the COVID-19 pandemic, found that individuals more satisfied with governmental entities and with a greater perception of participating in the decision-making process rated the government as more effective (Mizrahi et al., 2021). In our study, it can be argued that a perceived lack of clear and effective communication, as well as being excluded from the decision-making process, may have contributed to the perceived ineffectiveness of government response in certain areas (Levitt et al., 2022).

Furthermore, according to our findings and other recent literature, measures can be seen as ineffective and inefficient if considered illogical (e.g., restricting restaurant hours), leading to increased levels of worry, fear, and perceived risk (Lohiniva et al., 2022; Mækelæ et al., 2020). Indeed, a study in Finland with a dataset of over 10000 comments on Facebook and Twitter posts showed that measures were perceived as inefficient if seen as illogical, causing worries about the pandemic (Lohiniva et al., 2022). In turn, this negative impact of governmental actions on the population's well-being may impair compliance and behavior change (Thaker et al., 2018). However, we found no evidence that our sample had refused to comply with the measures imposed. Based on adults’ perceptions of several restrictions, it is possible to distinguish between accepting a social restriction and complying with it, on one hand, and perceiving said social restriction as effective, on the other (Mækelæ et al., 2020). For instance, people might consider closing small food establishments as an acceptable measure, but not as effective in controlling the outbreak (Mækelæ et al., 2020), or even as having more negative than positive outcomes, as highlighted in our results.

Our study has some limitations. First, results cannot be generalized since a non-probabilistic sample was used. Second, most interviews were collected online, and only five interviews were conducted in person. Recent literature has shown that online and in-person interviews generate similar volume and data content (Namey et al., 2020). However, online interviews may have hindered rapport and prevented participants from freely expressing themselves. To overcome this limitation, participants were given time to freely share their views on how the government managed the pandemic, without judgment.

Apart from the limitations disclosed above, this study makes an important contribution to the field of health psychology and public health. For instance, this study identified the features of perceived governmental and health entities' successful management during the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal, but mainly management weakness that possibly harmed adults’ well-being and hampered the correct adoption of preventive behaviors. According to our findings, governmental and health agencies should implement measures in times of health crisis, with the freedom to implement measures that cause individual discomfort, as adults are willing to endure it when perceiving beneficial societal outcomes. In any public health campaign, it is imperative to persuade the public of the effectiveness of any measure (Georgieva et al., 2021; Mækelæ et al., 2020; Quinn et al., 2013). It is therefore imperative that the least discomforting and most effective measures be implemented first since harsher measures can result in devastating consequences, such as loss of housing or mental health problems (Georgieva et al., 2021). Furthermore, measures aimed at delaying the spread of the virus should not be adopted by policymakers without objective evidence of their effectiveness, reinforcing the idea that public education campaigns should incorporate scientific-base information so that compliance with these recommendations can be maximized (Georgieva et al., 2021; Mækelæ et al., 2020).

On a communication level, governmental and health agencies must improve their communication skills to facilitate compliance and promote positive feelings, such as calm, safety, and trust. Hence, communication training, such as CDC-developed Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication training should be arranged for the people responsible for pandemic management (Quinn et al., 2013). Moreover, given the close relationship between public trust in governmental and health authorities, on one hand, and compliance with guidelines, on the other, it is paramount to prioritize the persuasion of the population regarding the effectiveness of the implemented measures in any public health campaign (Georgieva et al., 2021). Finally, effective communication strategies should be customized to people’s needs and priorities, resulting in informed decisions during a public health crisis (Leiras et al., 2020). Overall, this study helps to inform policymakers on how they can improve pandemic management skills, by implementing rules that are perceived as efficient, transparent, and enveloping the population in the decision-making process. At the same time, it becomes clear that communication skills need improvement when addressing adults from a wide age range. Adults’ acceptance skills and resilience could be further developed in clinical settings via acceptance and commitment therapy.

Aknowlegments

This study was partially funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT, 2020.10251.BD). AFV is supported by national funds through FCT, under the Scientific Employment Stimulus - Individual Call (reference 2022.05541.CEECIND/CP1751/CT0001). There were no financial or other relationships that led to conflicts of interest in the execution of this study and the report of the study findings. The authors thankfully acknowledge Alexandra Martins, Ana Paula Silva, Catarina Branco, Márcia Almeida, Margarida Evangelho, and Sara Silva for transcribing the interviews.

Authors’ contribution

Margarida Jarego: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Acquisition of financing; Investigation; Project administration; Resources; Visualization; Writing of the original draft; Writing - review and editing.

Pedro Alexandre Costa: Conceptualization; Writing - review and editing.

José Pais-Ribeiro: Supervision; Writing - review and editing.

Alexandra Ferreira-Valente: Conceptualization; Project administration; Supervision; Writing - review and editing.