Brazilian immigration to Portugal is a developing reality: according to the Serviços de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras (SEF, 2019), in 2019 Brazilian nationals were Portugal’s main foreign resident community, representing 25.6% of the total, the highest percentage since 2012. Moreover, Brazilian women represent a majority in the migratory process, as SEF also demonstrates that in 2019, out of the 151 304 registered and documented Brazilians, 86 158 were women. It is important to notice that this sample is comprised of legally documented Brazilians, with these figures possibly increasing when taking into account those that entered the country on a tourist visa and ultimately reside as undocumented individuals.

Brazilian interest in Portugal is not a novelty. Javorski and Iorio (2018) identify its origin in the early 1980s. Although an initially limited movement, it gained significant momentum at the start of the 21st century. Such mobility of people and different migratory flows reflect diverse motivations, from an escape and/or search for a better quality of life and safety, to professional aspirations.

The increasing and mainly feminine migratory flow has been the focus of studies and research aimed at identifying and articulating the power of women in the consolidation of their autonomy, pragmatizing and defining their experience and capacity to self-sustain and strive for their objectives on their own. In other words, withdrawing from the established invisibility within which their migratory displacement has been associated with men and seen to be dependent on them (Carlsson et al., 2016; Oliveira et al., 2017; Sana et al., 2018).

Feminine immigration brings the possibility of becoming pregnant in the host country. Due to the nature of unexpected maternity, it oftentimes carries a paradoxically heavy load of despair, fear of xenophobia, obstetric violence, and hope. According to Neves et al. (2016), this maternal setting places the migrant women in a position that contradicts the logic of populational aging present in the European Union, and therefore, within its important role in the sustainable development of its countries at the socioeconomic and demographic levels.

Notwithstanding, to think of migrant women solely in terms of sociodemographic and political advantages belittles other relevant instances of the perinatal period, for example, its subjectivity. Challinor (2012) denotes this moment as a process of negotiating with themselves and with those close to them, with strangers, and with the State. Through this lens, the author claims that the dynamics of these negotiation processes, along with the meanings attributed by the mothers, demonstrate how difficult it is for them to locate their power and diagnose its shortcomings through an identity analysis willing to go beyond social categories and labels.

Furthermore, Neves et al. (2016) emphasize the need to turn the migratory processes into something healthy and satisfactory, highlighting the healthcare field within the whole integration of the immigrants, especially during pregnancy, childbirth, and post-childbirth. This would ease the process of resilience in the face of natural migratory challenges, such as the struggle against discrimination for access to healthcare as well as cultural and linguistic barriers.

Therefore, resilience is presented as a new field of health and social science studies, having set itself apart due to its ability to subjectively explain how people can overcome certain types of adversity, while struggling to deal with others. Naturally, Brazilian women within a migratory context, not unlike men, go through conflicting experiences that have been denoted in several studies, such as acculturation and loss of social identity (Higginbottom et al., 2013; Maharaj & Bandyopadhyay, 2013; Tavoulari et al., 2015; Zolitschka et al., 2019).

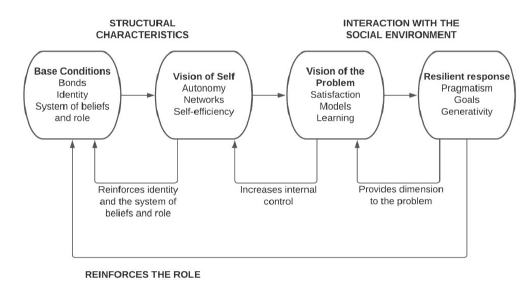

Conceptually speaking, several scholars present resilience in different ways, with distinct theoretical focuses. Some bring a rather deterministic view that leans towards the person’s biology, while others are more environmentalists focusing on the interaction between the subject and its context. From such a perspective, Saavedra et al. (2015), single out the dynamic process of resilience, a universal capacity that enables a person, a group, and/or a community to overcome difficult or problematic situations, recovering and re-signifying the scenario. A distinctive element of the construction of resilience is its preventive and proactive nature in the face of hardships, resisting adversity, and replacing the problematic situation in favor of learning and projection into the future. To facilitate understanding, Figure 1 illustrates the above-mentioned perspective by Guajardo (2011).

Therefore, given that immigration studies tend to centralize the negative aspects of the migratory process, and that the perinatal period is considered a delicate moment in women’s lives, it is important to focus attention on the resources mobilized by Brazilian women in Portugal to overcome hardships. This must be done while considering the dynamic processes involved with the interaction between adversity and resilient response. Guajardo’s (2011) Theoretical Model of Resilience involves four important aspects: Base conditions, Vision of self, Vision of the problem, and Resilient response. These aspects dynamically involve twelve dimensions - Identity, Autonomy, Satisfaction, Pragmatism, Bonds, Networks, Models, Goals, Affectivity, Self-efficiency, Learning, and Generativity - that describe different forms of integration of the subject with themselves, with others, and with their possibilities.

Thus, based on the Guajardo (2011) theoretical model ― structural characteristics and interaction with the social environment ―, this study aimed at understanding the adverse contexts and resilient responses of Brazilian women living in Portugal during the pregnancy-puerperium period.

Method

This study involves qualitative research of a descriptive nature, with the participation of 12 Brazilian women from several Brazilian States, currently living and having given birth in Portugal. It is important to emphasize that the interval between arrival in Portugal and pregnancy/birth is an average of 3 years and 8 of them were having their first child. Participants were recruited for convenience, and were sought through the virtual space on social networks, with the inclusion criterion being Brazilian women living in Portugal and who have experienced one or more pregnancies and childbirth(s) in this country.

As data collection instruments, a semi-structured interview was used which contained sociodemographic questions to characterize the participants, and ten guiding questions based on structural characteristics and interaction with the environment. This was consistent with the proposed theory and the aim of the study. Data collection took place between 6 months and 1 year after childbirth, via the Internet, through the Zoom platform, due to the Coronavirus pandemic, with an average duration of 40 minutes. The filming environment was strictly controlled, having the ethical security of the participants in mind, as the interviews occurred individually on previously scheduled days and times.

To analyze the data, this study utilized the Categorial Thematic Analysis proposed by Rodrigues and Figueiredo (2003). This form of analysis has two phases (first phase - Initial Read, Demarcation, Cut, First Merge, Notation, Discussion; the second phase - Initial Read, Organization, Notation, Final Discussion, and Redaction) that aim to find thematic classes derived from answers by the participants. This is followed by the construction of categories and their respective sub-categories. It is important to emphasize that, seeking to achieve greater reliability in the research, the Consolidated Criteria for Qualitative Study Reports (COREQ) were used (Booth et al., 2014). Furthermore, this study abides by all ethical norms in research involving human beings, having been authorized by the ethics committee of the Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE), through resolution 60/2020 from July 27th, 2020. The women voluntarily participated in the study, without any type of recompense, accepting the recording of the interview and giving their verbal consent after reading the Informed Consent Form (ICF) together with one of the responsible researchers/interviewers.

Results

The sociodemographic results showed the participation of twelve Brazilian women between the ages of 31 and 47, two of them having completed their high school education, four with a college degree, three with specializations, and three with a Master’s degree. Eleven were married and one was divorced. Regarding religion, three claimed no affiliations, one said she was a Buddhist, two affiliated with Spiritism, one was an Evangelical Christian and five said they were Christians. Occupations were diverse, with two psychologists, three teachers, two housewives, one systems analyst, one store manager, one civil servant (in Brazil), one photographer, and one housemaid. Five are currently working, one is focused on studying and six are unemployed. Their places of residence in Portugal were also varied, with five of them living in Lisbon, four in Aveiro, two in Cascais, and one in Odivelas. Three are originally from the Brazilian state of São Paulo, two from Rio de Janeiro, three from Bahia, one from Pernambuco, two from Pará, and one from Paraná.

The interview focused mainly on asking the participants about the experience of becoming pregnant in another country, detailing the pregnancy, childbirth, and post-childbirth, its challenges and overcoming them, as well as how they dealt with each perinatal phase within a migratory context. Following this, the study proceeded towards a thematic analysis, such as that proposed by Rodrigues and Figueiredo (2003), where a thematic class named Resilience emerged, along with two categories (Self-interaction and Social skills) and four subcategories (Base conditions, Vision of self, Vision of the problem and Resilient Responses), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Display of thematic class, categories, and subcategories from the maternal interviews.

| Thematic class | Categories | Subcategories |

| Resilience | Self-interaction | Base conditions |

| Vision of self | ||

| Social skills | The vision of the problem | |

| Resilient responses |

Considering resilience as a dynamic and circumstantial process developed through the construction and sharing of meanings socially built and attributed by the participants and their idiosyncratic experiences, it was possible to verify that this concept has several configurations. One of them refers to the first emerging category, namely, Self-interaction, and a second category, Social skills.

The Self-interaction category brings along the subcategories of Base conditions and Vision of self. The Base conditions subcategory is a system of beliefs and social bonds that permeates the memory of basic security that resourcefully interprets specific actions and results explicitly arising from the words of the participants. This was even more evident regarding identity (such as a judgment based on cultural values that they had about pregnancy, childbirth, and post-childbirth in a relatively stable form, having been built throughout their personal history) and bonds (such as placing value on primary socialization rooted in their personal history).

Some of the answers portray a moment in which identity was exposed while emphasizing the cultural differences between Brazil and Portugal, as well as its impact on the way they experienced the prenatal period, childbirth, and post-childbirth. For example:

“When I arrived, I knew it was different, but not that it would be so very different, right? From what I was used to all my life. You have a parameter and then you don’t have one anymore (…) I asked myself if I had made the right choice. If it was the right moment.” (ATdeO, 36, High School education and doula, married, from São Paulo - Brazil, living in Northern Portugal).

“I had different concepts. Every month, the doctor checking you might change and that made me even more insecure. In Brazil, I had only one doctor who saw me throughout my whole pregnancy up until childbirth. (DSV, 40, college education, from Salvador - Brazil, living in Lisbon).

These comments underline a certain level of discomfort or cognitive and affective dissonance concerning stable Brazilian cultural values, in the face of a new healthcare context in Portugal. Therefore, still taking into account the Base conditions, the matter of the bond emerges from the interviews in an emphatic way when the women report the experienced hiatus due to the absence and/or presence of the base family as support during this perinatal period. This can be seen in the following comments:

“I realized it would have been very different if I’d had family nearby because we have that bond, right? Something emotional with people and everything. It is not the same as being far away from your family and friends” (SCA, 33, married, college education, from Bahia-Brazil, living in Aveiro).

“My mother cooked lunch, prepared the juice I drank to have milk. She made it… her care was intense. She helped me a lot. If I’d been alone, I don’t know how it would’ve been” (DAF, 34, married, college education, from Pernambuco - Brazil, living in Porto).

Still thinking in terms of bonds, within the Vision of self subcategory, it is possible to detect aspects that portray autonomy and self-efficiency as factors that are behind the judgments participants make regarding their relationship with themselves and the possibilities of success when dealing with the perinatal experience in a migratory context. The following excerpts exemplify this:

“I feel like I’m inside a protocol. But every pregnancy is different, every birth is different. I know my body, I knew something wasn’t right, but the doctor just stuck to the protocol” (ATdeO, 36, High School education and doula, married, from São Paulo - Brazil, living in Northern Portugal).

“I studied, graduated, took courses, prepared myself and I would never check into a hospital where my husband was not allowed to be with me. I gave birth to my daughter at home. Just me, my husband, my mother-in-law and my other daughter, but with experienced people and friends accompanying me virtually” (MCdaS, 40, stable union, college education, from Rio de Janeiro - Brazil, living in Lisbon).

Considering the perspective that understanding resilience is intimately connected to the wide reach of the concept found in the aforementioned aspects, it is just as relevant to point out the second category, Social skills.

The Social skills category is directly related to two subcategories that surfaced: the vision of self and resilient conduct. The vision of the problem presented here refers to the perinatal experience in the context of immigration and its particularities, while resilient conduct alludes to the ways through which the participants acted and interpreted these performed actions. Thus, the vision of the problem became visible in the sense that some participants considered the perinatal experience in Portugal to have been positive, while others labeled it extremely negative.

“Getting pregnant here was a blessing, it was a gift I received. Everything was good, very good. In the first appointment with the family’s doctor, I was already given all the prescriptions to go to the hospital and get the tests. When I got back home, I received the appointment for the ultrasound” (JFF., 46, married, college education, from Pará - Brazil, living in Aveiro).

“Not having my parents; not having my family here; and with João not allowed to participate in the birth; it was very hard to accept” (RLB, 39, married, college education, from São Paulo - Brazil, living in Lisbon).

The resilient responses, the second subcategory of the Social skills category, encompasses pragmatism, goals, and the possibility to reach out to others for aid when dealing with a problematic situation during the perinatal period. It was noted that most of the Brazilian women that were interviewed displayed satisfactory resilient responses, even when faced with migratory and perinatal hardships, as seen in the following answers:

“When I learned that my husband would not be allowed to be with me, I was scared and upset. So, I told myself that I would not have my daughter in the hospital, alone and vulnerable to procedures I didn’t agree with. I prepared myself and gave birth at home with the people I love. It was magical” (MCdaS, 40, stable union, college education, from Rio de Janeiro - Brazil, living in Lisbon).

“At the time, I was very young. My Portuguese boyfriend had abandoned me and I didn’t have my family’s support. I didn’t have any money. I was helped by a friend and, thanks to her, I didn’t have an abortion. Today, my son is my greatest companion. I faced many things on my own, but I made it through” (UQV., 31, single, high school education, from Paraná - Brazil, living in the region of Lisbon).

Discussion

This research aimed at understanding the adverse contexts and resilient responses displayed by Brazilian women during the pregnancy-puerperium period, while living in Portugal. To achieve this, we utilized the lens provided by the theoretical model of resilience developed by Guajardo (2011), which places value on the history of the actual subject expressed through their present answer.

Therefore, the interviewed women’s personal and collective history is not objective nor stagnated, but rather colored by their interpretations.

Guajardo and Paucar (2008) define resilience as a way to interpret and act in the face of recurring problems throughout a subject’s history. Thus, the answers conveyed by the participants regarding feminine migration, associated with the perinatal experience, update their history while simultaneously transforming it. It is important to analyze, through a centralized discussion, the thematic class, the categories, and subcategories that surfaced under the scope of such a model.

The first category to surface, Self-interaction, may be interpreted through the categories of Base conditions and Vision of self. These aspects are presented by Guajardo (2011) as structural features. In other words, the cognitive-affective processes culturally built by the research participants throughout their story. Despite the obstacles encountered within the migratory and perinatal context, they enabled progress, generating resilient responses. These aspects were identified in the ATdeO (36) answer, when she questioned her decision to give birth to a son in Portugal, as well as in DAF (36), when she reported her discomfort with the differences in healthcare between Brazil and the host country.

The feeling of not belonging to the host culture was evident in this research, a predisposition of several types of vulnerability. However, as emphasized by Re et al. (2017), migrant women represent a particularly vulnerable group, and coping strategies play a vital role in the mental health aspect related to the migratory history and the new context (in this case the perinatal experience).

In this regard, it is important to highlight that emphasis is given to the situation considering the importance of the cultural fundamentals that each person forms. They are ultimately involved with one’s capacity to cover and negotiate necessary resources, as pointed out by Roberto et al. (2016).

Notwithstanding, it is also essential to observe the development of basic bonds, as discussed by Young (2013). Needs that are both universal and essential to healthy development, such as safe connections, autonomy, competence, the feeling of identity, freedom of expression, and validation of needs and emotions. When these elements are met within primary relations, combined with events and the environment in which one lives, the outcome is a person that values social networks rooted in personal history.

This judgment, which points to the placement of value on primary socialization, was evidenced in the answers of SCA (33) and DAF (34), as they convey the impact of their family’s absence during this perinatal period in Portugal. These ranged from objective absences connected to support in domestic activities to a subjective absence.

Such aspects directly influence how the participants see themselves (Vision of self), pointing to perspectives of autonomy, conviction about the role of social networks, and self-efficiency. ATdeO (36) and MCdaS (40) underscored how well they knew themselves and felt able and autonomous in the perinatal and migratory process. They understood the possibilities of success and were convinced about the role of social networks as a source of support. From this perspective, the healthcare team may be considered a physical and/or virtual social network, whose conditions of empathy and active listening generate security, awareness, and empowerment (Barkensjö et al., 2018).

Subsequently, the knowledge about perinatal health pursued by ATdeO (36) and MCdaS (40) emerged as a potential determining factor that influenced the mothers’ judgment about their possibilities of success when facing the migratory perinatal situation. Self-efficiency, specifically, is highlighted by Thorpe et al. (2018) and Lobo et al. (2020), which indicates factors associated with feelings of competence and confidence.

However, it is important to consider that beyond the autonomy and self-efficiency found in the participants’ answers, a vision of the problem (here the migratory perinatal situation) can be verified within the second category, named Social skills, in a polarized way. In other words, JFF (46) had a positive outlook on the Portugal experience, while RLB (39) expressed a negative judgment, even though both had very particular justifications. The former pointed to her satisfaction with the Portuguese healthcare team, the swiftness in receiving appointments and tests, and how safe and welcomed she felt in this context. The latter does not refer to the healthcare system and focuses on the absence of the family as an element of fragility that brings suffering in this situation.

According to Figure 1 presented by Guajardo (2011), the vision of the problem increases these women’s internal control; in other words, the vision they have of themselves. Furthermore, the co-present and/or present social networks are considered as ways to enrich the social capital and consequently strengthen the Vision of self, activating self-efficiency and functional Base conditions. From this perspective, Brasileiro (2019) conducted research about primiparous women and the utilization of virtual social networks (WhatsApp) as mechanisms of social cohesion and informational collaborative practices mediated by virtual spaces, as well as its products. Thus, these technologically mediated digital practices may be taken as a contemporary tool that helps in the promotion of resilience, or informational resilience in virtual social networks (Brasileiro, 2019).

In this same field, Roberto et al. (2016) performed a study about the processes of resilience with Cape Verdean immigrants in Portugal. Their results were able to verify the importance of family and the use of new existing technologies for their relations with distant family members. Similar to the data found in the present study, it was possible to verify the continuity of subjectivity processes between the country of origin and the host country.

Having said that, the Guajardo (2011) model points to the resilient responses by the participants as objective oriented action, a response sustained by or connected to an accessible vision of the problem (as recurring behavior). This is characterized by positive or proactive affective and cognitive elements facing an adverse situation with a historical-structural condition within the Base conditions. The women approached in this study thus drew from a system of beliefs and social bonds that permeated the memory of basic security and resourcefully interpreted their specific actions and results, as observed in the explanation offered by MCdaS (40).

Therefore, through a satisfactory vision of the problematic situation and placing value on the models and lessons from the experience, migrant women can display pragmatism, the construction of goals, and the capacity to create resolving alternatives as resilient responses. These aspects were identified in studies by Coutinho et al. (2014) and Beserra et al. (2019), having been corroborated by Zanatta et al. (2017) in research that highlights positive changes in women’s ways after the maternity of primiparous mothers. These were facilitated by the presence of a support network and a partner as emotional and instrumental support.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that the categories and subcategories interlace and occur simultaneously in the face of the situation. Moreover, all of them depend specifically on the diversity of these women’s realities, while constituting resilience and the interactive possibilities expressed in their answers.

Conclusions

This study of Brazilian women in Portugal validates the understanding of resilience not as deterministic or a finished result, but rather as a process that involves complexity and historical-cultural influences between conditions and contexts. Therefore, the process of perinatal resilience from the immigrants portrayed in this study had several configurations, such as the process of negotiation with themselves, those closest to them, and/or with strangers. They thus developed alternatives and possibilities of overcoming issues in the face of the several challenges that naturally come with pregnancy and puerperium.

As a result, resilience is here perceived as a naturally incomplete experience in a process of constant movement, in which interpretations and subjective aspects of the women that were studied changed with time and with the circumstances experienced throughout their lives. This corroborates the perspective of the theoretical model that was the basis for this study, when Guajardo (2011) points out the importance of the relationships between each person’s structural features and their interactions with the social environment in forming a resilient response.

In pragmatic terms, within the field of perinatal healthcare for migrant women, this study may be considered significant. It provides access and visibility - especially for the healthcare teams - to the possibilities of situations that can generate discomfort, while facilitating resilient responses in this phase of women’s lives, naturally attached to biological, psychological, social, and cultural fragility.

It is important to mention that this study presents limitations, as it refers to migrant women from only one country (Brazil). Thus, the obtained results cannot be generalized for studies with the same research scope, given that other methodologies might encounter complementary results. Another limitation that cannot be ignored is the fact that this study was conducted at the height of the Coronavirus pandemic, forcing the interviews to be carried out virtually. Moreover, because of this fragility, other studies must seek to deepen and geographically expand this field of research, not the least given that Portugal is a host country to several immigrants aiming to establish residence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG), Department of Health, Academic Psychology Unit, which had no involvement in the design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Regina L. W. de Azevedo: Conceptualization; Data Curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Validation; Visualization; Writing Original Draft; Writing Review & Editing. Carla Moleiro: Conceptualization; Data Curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing Original Draft. Wahriman A. de Araújo: Conceptualization; Data Curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Validation; Visualization; Writing - Original Draft; Writing - Review & Editing.