Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Economia Global e Gestão

versão impressa ISSN 0873-7444

Economia Global e Gestão vol.17 no.3 Lisboa set. 2012

Why do companies withdraw from cooperative processes: contributions to the management of inter-organizational networks

Por que as empresas se retiram dos processos cooperativos: contributos para a gestão das redes interorganizacionais

Leander Klein* & Breno Pereira**

* Master in Business Administration, Federal University of Santa Maria, Brazil. Studies and research in the subject of Interorganizational Networks. E-mail: kleander88@gmail.com

** PhD in Business Administration from Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Associate Professor at the Federal University of Santa Maria and Professor of the Post Graduate Management course (PPGA/CCSH/UFSM), and studies interorganizational strategies, conflict and cooperative innovation. E-mail: brenodpereira@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

CEOs use cooperation networks among companies as strategies to perform in the market. However, it is argued that studies on this kind of cooperation, from both a theoretical and an empirical point of view, have overemphasized the reasons and benefits of cooperative strategies, and under emphasized the factors that lead some companies to withdraw from horizontal networks. Thus, the objective of this work is to develop a conceptual framework for analyzing the factors that lead companies to withdraw from their collaborative arrangements. The conceptual framework proposed lists three stages during the formation and development of the networks: 1) background for collaboration; 2) collaborative processes, and 3) perceived outcomes of the collaboration. In simplified terms, it can be said that different aspects are related to the output of company networks, and the evolution of the network depends on its capacity to overcome the stages of development.

Key words: Cooperation, Relationships among Companies, Closure of Networks, Inter-organizational Networks

RESUMO

Os gestores de empresas usam redes de cooperação entre empresas como estratégia para atuar no mercado. No entanto, argumenta-se que os estudos sobre este tipo de cooperação, tanto teóricos quanto empíricos, têm enfatizado demais as razões e os benefícios dessas estratégias de cooperação, e focado pouco nos fatores que levam algumas empresas a retirarem-se de redes horizontais. Assim, o objetivo deste trabalho é desenvolver um quadro conceitual para analisar os fatores que levam as empresas a sair das redes de colaboração. O esquema conceitual proposto lista três estágios da formação e desenvolvimento das redes: 1) antecedentes para colaboração; 2) os processos de colaboração, e 3) os resultados percebidos da colaboração. Em termos simplificados, pode-se dizer que diferentes aspectos estão relacionados à saída de empresas das redes, e que a evolução da rede depende da sua própria capacidade para superar os estágios de desenvolvimento.

Palavras-chave: Cooperação, Relações entre Empresas, Término de Redes, Redes Interorganizacionais

INTRODUCTION

The development of inter-organizational networks is a form of strategic market activity involving the compatibility of skills, diversification of information, learning and innovation (Lin et al., 2009). As such, they can reduce the environmental uncertainty of their partner organization, help meet each companys resource needs and be an alternative source of competitive advantage (Corsten et al., 2011). Thus, the companies cooperate with each other in order to acquire benefits that will help them face the demands arising from their fields of activity. According to Pereira and Pedrozo (2004, p 70), "the formation of cooperatives between two or more organizations constitutes a strategic decision to share risks, share resources, access new markets, achieve economies of scale, obtain synergies, and finally to ensure competitive advantage".

Given this framework of potential gain, it is believed to be unlikely that a company would leave a network. However, in some cases, this is exactly what happens. For Wegner (2011, p.19) the benefits cited above, "conceal the fact that the cooperation demands support in its creation, coordination and maintenance." This type of project requires costs to cooperate, and its management incurs problems, conflicts and difficulties that impede many business cooperation initiatives from fully reaching their goals (Pereira et al., 2010).

For Scherer (2007), in fact these challenges translate into the limitations of both the network and the individual firms limitations, which are as much due to internal as they are external factors. The networks internal limitations are determined by the availability of resources (physical, human, organizational and financial) as well as the ability to coordinate these resources when used in the network. The external limitations are expressed by institutional factors governed by "the rules of the game" in the networks operational environment.

One study that found a relationship between networks being opened and closed is that of Toigo and Alba (2010). They found that in the regions of operation of the cooperation network program in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, only 26 out the 41 networks created since 2000 in the area surveyed remained active. Therefore, 37% of the networks established were closed. Among the reasons for theses companies network failure, we highlight factors such as problems in the transfer of knowledge between agents (Yayavaram and Ahuja, 2008), lack of confidence and learning (Parast and Digman, 2008), commitment (Castro et al., 2011), asymmetric information (Venturini, 2008), costs of cooperation (Adler and Kwon, 2002) and lack of value creation (Ahola, 2009).

It has been observed that many networks are not able to consolidate their structures with their management models. Negative processes and factors may come up in these relationships that mean it is no longer worth participating in the network (Pesämaa et al., 2007). Thus, if networks actually provide benefits and competitiveness, why do some companies deviate from them? What are the reasons for this withdrawal? Why do they leave? Finding the answer to these questions is precisely the challenge that inspires this study as we attempt to shed new light on the research found on this topic. The objective of this work is to develop a conceptual theoretical framework of the problems and difficulties that can arise within inter-organizational relationships. Theories and specific studies were used as the basis to illustrate this conceptual framework in an attempt to explain "why companies leave their networks?"

The study of the subject is justified by an attempt to consolidate a body of work based on the theory of the phenomenon, since in view of Lima (2007) and Cropper et al. (2008), the study of inter-organizational networks has focused on analyzing the success of the relationships between companies, with little concern given to understanding the reasons that lead to the failure of these ventures. In addition, diagnosing the reasons why a company might leave its network could contribute to the networks stages of formation and development, buffering problems, conflicts and difficulties that arise during this process and in the management of the networks.

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE LIMITATIONS OF INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL NETWORK PERFORMANCE

The studies by Sadowski and Duysters (2008) tried to shed light on some specific causes of partnership failures between companies. They examined the termination of strategic technology networks using three levels of instability: unexpected external contingencies, inter-firm rivalry, and coordination problems (complexities of network management). Moreover, they characterize the external contingencies as alignment problems with the conditions of the surrounding area, such as changes within the technological or commercial environment.

With regard the rivalry between companies, Sadowski and Duysters (2008) related the success (or failure) of a partnership to the collective alignment process. They give the example of the efficiency of dynamic strategies with the balancing of interests and priorities within the network. Since the partner companies remain independent in inter-organizational networks (in contrast to the mergers and acquisitions), the balance of the interests and background of the partner companies involved becomes central, and is connected to a greater or lesser complexity of network management (Sadowski and Duysters, 2008).

The abovementioned authors point out that as companies engaged in a strategic alliance differ in market positioning, organizational structure or management style requires them to make a more balanced and continuous contribution to the network. This contribution must be rooted in corporate strategy and requires commitment, financial strength and confidence. Unequal contributions increase the chances of an unexpected termination of a partnership.

For the purposes of the study, Sadowski and Duysters (2008) collected primary data from MERIT-Cooperative Agreements and Technology Indicators. Using a sample of 48 strategic alliances from different high tech industries, they found through interviews that managers had different perceptions on the subject. The results indicated that the following were among the main reasons and problems faced by company strategic alliances leading to failure: 1) the difficulties of generating expected technological results (when dealing with technological networks); 2) low generation of business results; 3) problems related to communication within the alliance; 4) complexity of managing the alliance; and 5) high maintenance costs.

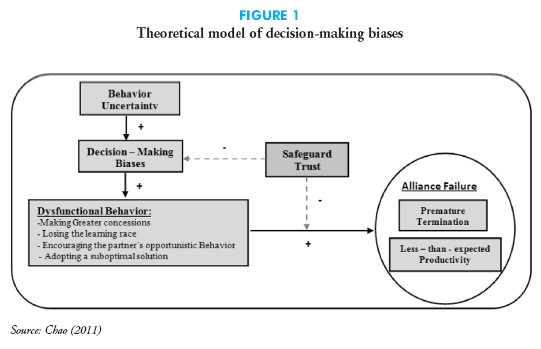

Chao (2011) confirmed in his studies that a networks principal company can influence that network when making a decision, and thus cause developmental problems or even result in the networks termination. For him, the collaboration of companies in strategic networks can be seen as a series of decision-making processes involving the interaction between the actors (business partners) of the network. He argues that in the decision-making process, biases can arise out of the uncertainty caused by ambiguous intentions or unpredictable behaviors of the network partners. Figure 1 shows the model proposed by Chao (2011).

In the various phases of the networks lifecycle, misperceptions may foster decision-making biases which in turn, can cause dysfunctional behaviors which negatively affect the performance of the partnership (Chao, 2011). This dysfunctional behavior would then lead the network actors to make greater concessions, lose assimilated learning, adopt standards of inferior quality, and facilitate the opportunistic behavior of the partnering company. These are the biases (trends) that can occur in the decision-making of companies in the network, when an excess of trust is put into one partnering company and when companies interact with uncertainty when they work together.

In this process, the author states that biases in decision-making can be reduced if the network can make a partner's behavior more predictable by using different devices such as contracts. In «Transaction costs economics», Williamson (1985) argues that behavioral uncertainty can be reduced by the implementation of safeguards to mitigate the opportunistic behavior of a partner.

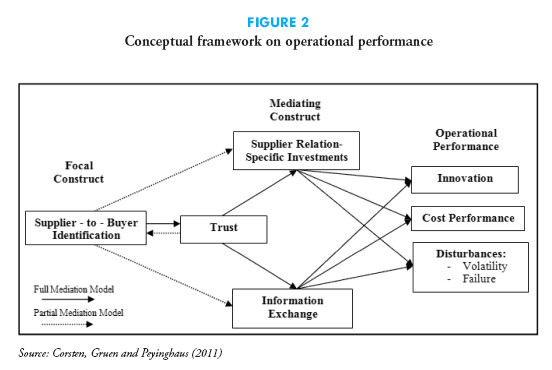

On the other hand, Corsten et al. (2011) conducted a study aiming to advance the understanding of the role of inter-organizational relations in the operations of networked companies. The study hypothesizes that the companies identification prior to the formation process of the relationship, along with trust (directly) increase investments in specific assets and foster the exchange of mutual information and knowledge sharing. These factors in turn, increase operational performance, cost performance and innovation, reduce network volatility and the possibility of failure. Figure 2 shows their proposed conceptual model.

Corsten et al. (2011) more specifically state that the organizations previous identification is related to the processes and events which they use to establish links to organizations, as a way of strengthening relationships in a supply chain. This process can be mediated by two important theoretical relationship factors. First, starting from the conceptualization of transaction costs, Corsten et al. (2011) suggest that the companies identification is directly linked to the specific investments made, which in turn improves operational performance. Second, this process fosters information exchange, which is an important precursor to operational success. In both cases, the effect may be due to an increased level of confidence (Irland and Webb, 2007).

At the operational level, Corsten et al. (2011) evaluated three issues: (1) innovation, i.e. the development and commercialization of new products and services, or processes and methods; (2) cost performance, i.e. achieving the lowest cost; and (3) operational disturbances such as volatility and failures. Through a survey of 346 cases of supplier-buyer relationships in the automotive industry, they indicate that the specific investments and exchange of information play different but complementary roles in influencing operational performance, in addition to minimizing the volatility and the chance of failure of the relationship created.

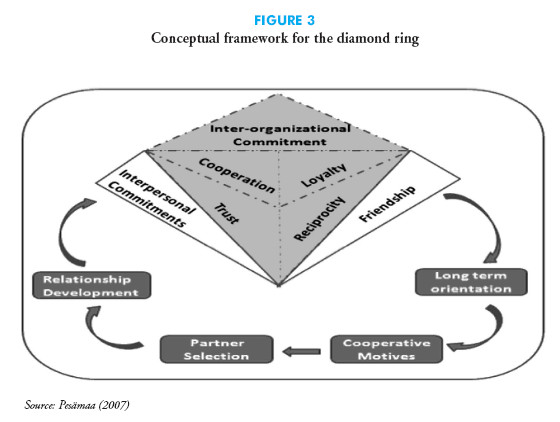

The objective of Pesämaas studies (2007) was to determine the development of relationships in inter-organizational networks. First, he lists the advantages of an inter-organizational network, such as: legitimacy, ability to share costs and risks, and enhance and share resources and skills. Pesämaa also lists some disadvantages of this strategy, such as: commitments and costs required for membership; the risk of investing in a relationship which may not give the expected return; and decreased flexibility of companies.

In developing his framework, Pesämaa considers some points of which those responsible for network management should be aware. These led to the development of the "diamond of inter-organizational networks" (Pesämaa, 2007). Figure 3 shows his proposed study design (diamond).

Pesämaa (2007) discusses the key points for the development of inter-organizational networks and describes stages of development, placing the following ideas: 1) the basic premise is that networks take "time" to develop, and thus the long term orientation is considered an important prerequisite for inter-organizational relationships; 2) the cooperative process involves motives for entering inter-organizational networks, which are defined before the interaction occurs and influence the success of the network; 3) after considering the reasons for entering, the partners are carefully selected. This would be the next phase of developing relationships between companies; 4) after selecting partners, the companies begin a stage that goes beyond friendship to a relationship involving commitment, trust and reciprocity; and 5) the final phase is stability and maturity. This phase of relationship development includes three important mechanisms: the commitment, which reflects the company's intentions and promises; cooperative strategies, which are reflected by shared goals and decisions; and third, loyalty, protecting the relationship.

The studies cited here show aspects and key factors that are relevant to the formation process and development of inter-organizational networks. It is also possible to see some variables that can lead to difficulties and problems in networks and even cause companies to remove themselves from those networks. The framework of Chen (2010) includes some of these factors, dividing them into three distinct stages: (1) the history of the enterprises collaboration; (2) the collaborative process; and (3) the perceived effectiveness of the collaboration. He justifies the choice of these three stages by pointing out that much of the existing literature focuses only on one of these three stages of collaborative relationships.

PROPOSED CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK: SUCCESS/FAILURE OF NETWORK ORGANIZATIONS

Based on theories and models discussed previously in the literature, a conceptual scheme of the study was proposed, outlining key study factors in each phase (stage) of the establishment of cooperation networks between companies. The proposed model is outlined in Figure 4.

Through the integration of different theoretical perspectives, we identified factors and conditions that must be observed when driving an organization to form a partnership through inter-organizational networks. The expectations (the possibility of future benefits) surrounding inter-organizational networks are not considered here. We consider the factors to be analyzed by organizations for partnership formations that can cause problems if not given due attention. Oliver (1990) states that the factors and reasons for the formation of the relationship involve the causes and contingencies that induce the formation of inter-organizational settings, and not the future expectations generated. In the following sub items, the proposed model is explained in greater depth and deepens it more as the text evolves.

Background for collaboration

The decision of a company manager to partner with a particular organization can be influenced by the difficulty of finding partners, known as "supply-side imperfection" by Van Slyke (2007). The different strategic orientations of the partners can be a problem for network management, as it means dealing with distinct perspectives for each partner company. Graddy and Chen (2006) found that even if the organizations were willing to comply with the funding requirements for forming a network, they were limited by their potential ability. Hitt et al. (2000) and Tsang (2002) suggest that the selection of partners is an important factor in determining the success of the alliance because of the need for the alignment of specific resources and their continuous exchange.

Douma et al. (2001) consider that the difficulty is to adjust business strategies, linking issues such as complementary balance of information, mutual benefit and harmony among member companies. On some occasions, an organization is selected as a partner simply because there are few companies with alternative and similar services for the formation of a given network. According to Chen (2010), partnerships that are formed solely on the availability of partners are usually not successful in their ventures.

With reference to social ties, Gulati (1995) argues that an organizations ability to join an alliance is limited by their social network. A complex set of relationships between members of a social system of different size, resources and skills brings about the possibility of forming a relationship. Work by Burt (1992) sought to specify how different positions within a network of relationships affect the actors opportunities. For example, an actors position within the network, represented by the number of inter-relationships with other actors, could reinforce the power relations of the networks marginal players (Balestrin et al., 2010). Thus, the behavior of economic agents is constrained by social structures that are built over time (Granovetter, 1994), and can determine the failure of the arrangements organization.

Chen (2010) states in his studies that partnership between companies is driven by organizational motivations, which convey legitimacy to the other partners and stakeholders. Partnerships, alliances or business networks are seen as desirable, and are often encouraged and requested by the owners and financiers of companies (Provan et al., 2008; Bryson et al., 2006). Institutional Theory describes the conformist or isomorphic behavior of companies as a way of obtaining legitimacy in from of their key stakeholders. This theory suggests that strategic alliances may stem from an organizations desire to improve its reputation, image, prestige, or congruence with prevailing norms in its institutional environment (Dimaggio and Powell, 1983).

The theory of resource dependency focuses on increasing critical organizational resources or reducing the need for resources through strategic alliances (Gronbjerg, 1993). The inter-organizational network can provide access to a logo, co-branding, names and other basics that give companies legitimacy (Haahti and Yavas, 2004), and this can generate economic returns. Pesämaa (2007) also argues that a company can gain legitimacy from the involvement in inter-organizational relationships. The legitimacy summarizes the companys recognized activities, by their main stakeholders (Lawrence et al., 1997). Yet the inability of the network to ensure its legitimacy among stakeholders can be a determining factor in the failure of the business. Pereira (2005) believes that there are network partners who seek something more than the economic returns of their business. Their intrinsic goal is to maximize their social gain and entrepreneurial legitimacy. For this reason, they insist on being network board members, which will guarantee them better social visibility. They go from being simple businessmen, business owners, to being agents of transformation for dozens of business. Their dynamic and conciliatory characters ensure the sustainability of the network, but not its evolution.

Collaborative processes

In a collaborative relationship, there is a set of processes and activities related to network development that help guide the flow of information, manage the depth and breadth of interactions, and improve the complex and dynamic exchanges between the partners. This process develops collaborative factors that include the managerial aspects and governance issues in an inter-organizational relationship. In addition, it identifies key points that reflect how committed the parties/partners in the relationship are to: sharing complementary resources, the promotion of inter-organizational trust, the ability to change policies, the procedures of partner companies and the costs of maintaining themselves within the network.

The governance and management of networks are aspects that relate to network development, the achievement of proposed objectives, and refer to a set of rules, restrictions, incentives and mechanisms implemented to coordinate the participants of an organization (Wegner and Padula, 2010). What differentiates the management of business networks from corporate governance is that the actors are companies, and not individuals. In a cooperative network, the management is the result of a negotiation process between the respective company leaders participating in the agreement (Wegner and Padula, 2010). These companies agree to lose their freedom to a certain extent, and allow the network management to coordinate specific aspects of their business under the system of rules created by the group (Albers, 2005).

By definition, inter-organizational cooperation involves the interaction of two or more partner organizations in the joint provision of services and/or supply of a product, or another common goal that they want to achieve. These companies bring with them their own culture and management practices which differentiate them from other partners. Thus, it is through cooperation that these differences become dormant and need to be adjusted in order for the network to succeed (Wegner et al., 2008). The difficulty inherent in this process is that the cooperation demands major coordination efforts, generating managerial complexity and uncertainty (Park and Ungson, 2001). The question asked here is: how did the network management lose some of its members? What was the process of network decision-making that prompted the departure of some members? Did the way the network was managed influence the withdrawal of some members, or even its failure?

Enterprise networks need to specify roles and responsibilities and define and coordinate the daily operational tasks for each partner, in order to effectively manage the operations and the agreed objectives (Chen, 2010). These administrative aspects are seen as key to achieving effective collaboration (Bardach, 1998; Cropper, 1996).

Another issue when dealing with networks is that organizations enter into partnerships where partners can contribute resources or capabilities that are not held by another organization (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978; Dyer and Singh, 1998), creating new benefits for the individual organization. However, some actors, which here we call entrepreneurs, start to see new opportunities for their business development outside of the networks. Thus, they look for strategic alternatives to leaving the networks, i.e., minimizing their costs, while maintaining the benefits of belonging to a network. These companies realize that they will only continue to grow in a lasting and sustainable way outside of the networks, given the limiting characteristic of network performance. The companies then break with the networks, increasing the risks associated with their business as they no longer have the networks protection, and enter the market alone competing with both other networks and also their former partner network.

To minimize the opportunistic agent of business, Fryxell et al. (2002), Koza and Lewin (2000) emphasize that the agents trust and commitment is required to establish trade in cooperative networks and the success of this type of strategy. These factors are important as they will bring a closer relationship between the parties; facilitate the exchange of the total resources; and influence reciprocity, frequency and intensity of interactions among network actors (Hansen, 1999; Tiwana, 2008). Trust creates a context of social cooperation conducive to sharing information and learning (Dyer and Chu, 2003; Muthusamy and Whyte, 2005). Verschoor and Balestrins (2008) argue that trust brings the agents together and the resulting relationship ends up extrapolating the economic plan.

The difficulties are compounded in networks where actors trust and commitment are weak or nonexistent. For Bachmann et al. (2001) and Uzzi (1996), without a minimum of trust and commitment it is almost impossible to establish and maintain successful inter-organizational relationships for a long period of time. Larson et al. (1998) state that lack of trust can be a barrier to the development of knowledge and effectiveness of inter-organizational learning. Sadowski and Duytsers (2008) argue that the failure of the network originates from a poorly managed partnership, where there is no trust between the partners involved. The lack of these factors may be related to other problems such as asymmetric information and opportunism.

Williamson (1975) states that asymmetric information between actors involved in the process proved harmful to the companies performance, and even generated a cost for them. This variable refers to the appropriation of profits by a company holding specific information associated with a particular transaction (Fian, 2002). For Venturini (2008), this privileged information could be either exogenous and associated to relationships with agents outside the network, or endogenous, arising from exchanges between the participants. The supposition of opportunism in a situation where there is asymmetric information can increase costs or decrease the benefits of the other party, who is unable to monitor or control the actions of an opportunistic agent (Byrns and Stone, 1996).

Opportunistic behavior exists when one actor acts strategically, seeking to realize their own interests over the interests of other actors and in disobedience of the rules (Williamson, 1985). Thus, as soon as the network companies no longer receive similar information and begin to see opportunistic behavior, complexity and uncertainty increases in the commercial situation (Lima, 2007), and the firms begin designing "safeguards" to avoid being made victims (Williamson, 1985).

From this perspective, we address the issue of costs for companies to remain in the network (Adler and Kwon, 2002). From the standpoint of Jarillo (1998), the basic assumption is that a network of companies will continue to exist if the gains from cooperation exceed the profits that can be obtained outside the network. If this does not occur, companies seek options outside the network to maintain the same standard at a lower cost. For Park and Ugson (2001, p. 47) a network is able to maintain its structure and remain an efficient mechanism for inter-firm transactions, while the economic benefits of the partners outweigh the potential costs of managing the alliance. Sadowski and Duysters (2008) and Pesämaa (2007) consider this to be a problem or disadvantage of inter-organizational networks.

Finally, there is the question raised by Olson (1971) in the The Logic of the Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, which deals with asymmetric investments generated by the strong appeal of self-interested individuals. The author states that "the reason to belong to a particular group is revealed by the chance or possibility of getting something through that membership" (Olson, 1999, p.18). This concept is the result of individuals having different reasons to achieve a common goal (Olson, 1999). In other words, an individual in a group can associate a higher value to some collective goods, and he will be willing to invest more in order to obtain it. However, "not all individuals in the group give the same value to the goods, despite having an interest in consuming it. These individuals have incentives not to contribute, since the group will do it anyway. They are free riders (Pereira, 2005, p. 36).

Perceived results of the collaboration

This part of the work addresses four dimensions of perceived effectiveness: (1) Achievement of the goals and objectives; (2) Inter-organizational Learning; (3) Reduction of the autonomy of the partner companies; and (4) Innovation and value creation. The first dimension is the networks guiding task and corresponds to the primary purpose of funding efforts by business partners in inter-organizational relationships. The second dimension is more related to capacity building and improvements of the network companies. The third refers to the interdependence of the companies, and the last to the allocation and generation of new knowledge and skills.

The purposive-rational model of organizational effectiveness assumes that organizations are designed to achieve certain goals (Etzioni, 1964). Successful collaboration requires an alignment or compatibility of objectives, and the scope thereof. Companies come together for common goals that are mainly focused on access to learning and innovation; reduction of costs and risks; the increasing of scale and market power; the deepening of social relations; and of services, products and infrastructure provided by the network (Verschoore and Balestrin, 2008).

In Wegner and Padulas (2010, p. 74) view, the "continuity of cooperation is based upon the ability to achieve the proposed goals and make members more competitive." More specifically, for Pereira and Pedrozo (2004) and Pereira et al. (2010), it is inherent in studies on the management of networks that conflicts are created when organizational goals are not achieved by an alliance member. The emergence of conflicts can occur if one or more of the objectives outlined are not met, leading to dissatisfaction and misunderstanding between the partner companies, and encouraging companies to leave the network.

The second result of collaboration highlights inter-organizational learning. A perspective related to learning emphasizes that alliances emerge as an organizations strategic response to environmental changes that require improvement in skills, knowledge and technological capability (Kogut, 1988). Pardini et al. (2006) believe that inter-organizational learning is not promoted in isolation. This type of learning is the result of the confrontation and union of the knowledge available through the experiences of the organization. Learning is relevant because substantive innovation requires that students learn and communicate with each other in a way that allows for transformation (Handley et al., 2006).

In Estivaletes (2007) studies, the author identified several factors (barriers) that may hinder the learning process in organizations that operate in the network; these include the following: asymmetries of power; individualistic vision, lack of clarity and transparency, conflicts between companies, geographic location of the business, ineffective communication process, and lack of cooperation and collective spirit.

This perspective addresses the networks difficulty in generating new benefits and innovations for its members (Pereira, 2005 and Ahola, 2009). Innovation can be defined as the introduction of new elements into production, provision of a service, operations of an organization – raw materials, labor, equipment and mechanisms used – in order to reduce costs and/or increase the quality of the product (Damanpour, 1991; Reichstein and Salter, 2006).

Just as the activities of processes management extend in an organization increasingly over time, network links and action routines reduce technological, social and economic uncertainties by way of the innovation process (Pyka and Küppers, 2002). For Westerlund and Rajala (2010), there is a direct and positive relationship between innovation and the process of collaboration in networked enterprises. In the opinion of Pereira et al. (2010), although the horizontal networks are formed for other reasons in many cases, innovation becomes the driver of the sustainability of these enterprises. These authors also explain that new knowledge will created by the action of all actors involved in the network environment, and not by their strategic commitment.

Another difficulty that many inter-organizational networks face is the reduction of partner companies autonomy (Chen, 2010). In a collaborative alliance, the partners deal with the tensions over organizational autonomy and the power differential in the relationship (Bryson et al., 2006). In an effective partnership, Cummings (1984) points out that members of the network need to spend time "day to day" controlling their activities, in order to be able to focus on the activities of the collaboration.

From Chens (2010) perspective, reducing the organizational independence of the companies participating in the network leads them to spend less time, resources and efforts on the continuation of the relationship, undermining the stability and continuity of the network. However, the reduction of organizational autonomy as a negative result of collaboration is likely to be seen as a threat to the networks survival.

DISCUSSION AND FINAL THOUGHTS

Inter-organizational relationships can refer to either the actor or the context. When viewed as an actor, a network is an entity that can be analyzed independently. On the other hand, a network is made up of smaller entities such as organizations, and can be seen as a surrounding environment, in other words, passive in the context (Alves et al., 2010). Sydow (2006) points out that compared with individual organizations, the network management organizations imply significant changes being made in the functions and roles of traditional management. Managers cannot worry only about developing and implementing strategies at the individual firm or business area level. This task is accompanied by the need to formulate and implement collective strategies that meet the interests of participants.

The challenge of managing inter-organizational relationships is associated with obtaining information about required skills, needs, reliability and other attributes of potential partners. More specifically, to understand how to select partners, how to divide and develop new knowledge, how to increase the level of interaction between partners, and how companies included in the networks sharing their expertise can assist in achieving higher levels of competitiveness and minimizing dislocations and conflicts among members, and their possible departure.

There are many dimensions to interactions provided by collaborative work between businesses; these, include the decision of the administration, combined resources, exchange of information and expertise, as presented in the proposedanalytical scheme. The actors establish contacts that lead to the development of their capital stock, creating information flows and the combination of market knowledge, strategy, competitors, technologies and processes that can be used for the benefit of the companies involved and enhance performance. However, the governing structures of networks face the difficulties of possible dysfunctions arising from decisions and ways of managing networks, and how these could be avoided, or at least eased. The key questions are: To what extent does a company consider it an advantage to be part of a network? Given the investment (in terms of resources: financial, personnel and time) how long does it remain in the relationship?

This study analyzed different factors and aspects that should be observed in the designing and implementing of inter-organizational networks, the impacts on the perceived results of collaboration, and the relationship with companies that leave the network. Specifically, the objective of this study was to examine the theories related to corporate networks to find the reasons why companies leave networks, and integrate it in a synthetic and didactic vision.

Most work on inter-organizational collaboration requires a systematic of various aspects and factors related to this strategy. This study hypothesized on how the negative effects of the requirements and aspects of network effectiveness may lead companies to exit the networks as well as the possible failure of those networks. We therefore attempt to form a line of thought that sheds light on the inter-organizational relationships and the problems related to them.

An understanding of relational dynamics between background, processes and outcomes of collaborative relationships can help organizations take proactive steps to deal with potential problems and conflicts in the formation and development of inter-organizational networks. The aim of this work is also to contribute to the development of a theoretical foundation of the phenomenon, because as Chen (2010) stated, little academic attention has been devoted to the understanding of factors that improve the functioning of inter-organizational partnerships despite their increase. Moreover, can be observed the interdisciplinary theories, systematizing the applicability of a consolidated theory in the field of inter-organizational networks.

This opens up a range of new possibilities for research in hitherto unexplored fields of administration, specifically in the management of networks. This opened up a number of issues that have not yet been addressed in previous studies: a) which factors in the analytical framework most influenced the business partners discontent and possible departure from the network?; b) how do the background and collaborative processes influence and determine the perceived results of the network?; c) what determines the greatest network performance?, d) are the theoretical approaches used in this study sufficient to explain the phenomenon? Future theoretical and empirical studies should be conducted to answer these questions and increase understanding and also to refute or corroborate the relationships shown.

REFERENCES

ADLER, P. & KWON, W. (2002), «Social capital: prospects for a new concept». Academy of Management Review, 23(1), pp.15-22. [ Links ]

ALBERS, S. (2005), The Design of Alliance Governance Systems. Kölner Wissenschaftsverlag, Köln. [ Links ]

AHOLA, T. (2009), «Efficiency in Project Networks: The role of Inter-Organizational Relationships in Project Implementation», Doctoral Dissertation, Helsinki University of Technology, Finland. [ Links ]

ALVES, J. N.; BALSAN, L. A. G.; MOURA, G. L. & NAGEL, M. B. (2010), «As relações de confiança, aprendizagem e conhecimento em uma rede do setor imobiliário».XIII SEMEAD – Seminário de Administração. [ Links ]

BACHMANN, R.; KNIGHTS, D. & SYDOW, J. (2001), «Trust and control in organizational relations». Organization Studies,22(2), pp. 337-365. [ Links ]

BALESTRIN, A.; VERSCHOORE, R. V. & REYES, Jr. E. (2010), «O campo de estudo sobre redes de cooperação interorganizacional no Brasil. Revista de Administração Contemporânea (RAC), 14(3), pp. 458-477. [ Links ]

BARDACH, E. (1998), Getting Agencies to Work Together: The Practice and Theory of Managerial Craftsmanship. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

BRYSON, J. M.; CROSBY, B. C. & STONE, M. M. (2006), «The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: prepositions from the literature». Public Administration Review, 66(Special issue), pp. 44-55. [ Links ]

BURT, R. S. (1992), Structural Holes: The Social Structures of Competition. Harvard University Press, England. [ Links ]

BYRNS. R. & STONE, G. Jr. (1996), Microeconomia. Makron Books, São Paulo. [ Links ]

CASTRO, M.; BULGACOV, S. & HOFFMANN, V. E. (2001), «Relacionamentos interorganizacionais e resultados: estudo em uma rede de cooperação horizontal da Região Central do Paraná. Revista de Administração Contemporânea (RAC), 15(1), pp. 25-46. [ Links ]

CHAO, C. Y. (2011), «Decision-making biases in the alliance life cycle: implications for alliance failure».Management Decision, 49(3), pp. 350-364. [ Links ]

CHEN, B. (2010), «Antecedents or processes? Determinants of perceived effectiveness of interorganizational collaborations for public service delivery». International Public Management Journal, 13(4), pp. 381-407. [ Links ]

CORSTEN, D.; GRUEN, T. & PEYINGAUS, M. (2011), «The effects of supplier-to-buyer identi?cation on operational performance – An empirical investigation of inter-organizational identi?cation in automotive relationships». Journal of Operations Management, 29, pp. 549-560.

CROPPER, S. (1996), «Collaborative working and the issue of sustainability». In C. Huxham, C. (Ed.), Creating Collaborative Advantage. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 80-100.

CROPPER, S.; EBERS, M.; HUXHAM, C. & RING, P. S. (2008), «Introducing inter-organizational relations». In S. Cropper, M. Ebers, C. Huxham, and P.S. Ring (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Inter-Organizational Relations. Oxford University Press Inc., New York, pp. 3-30. [ Links ]

CUMMINGS, T. (1984), «Transorganizational development». Research in Organizational Behavior, 6, pp. 367-422. [ Links ]

DAMANPOUR, F. (1991), «Organizational innovation: a meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), pp. 555-590. [ Links ]

DIMAGGIO, P. J. & POWELL, W. W. (1983), «Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields». American Sociology Review, 48, pp. 147-160. [ Links ]

DOUMA, M.; BILDERBEEK, J.; IDENBURG, P. & LOOISE, J. (2001), «Strategic alliances. Managing the dynamics of ?t». Long Range Planning, 33, pp.79-98.

DYER, J. H. & CHU, W. (2003), «The role of trustworthiness in reducing transaction costs and improving performance: empirical evidence from the United States, Japan, and Korea». Organization Science, 14(1), pp. 57-68. [ Links ]

DYER. J. H. & SINGH, H.H. (1998), The relational view: cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), pp. 660-679. [ Links ]

ESTIVALETE, V. F. B. (2007), «O Processo de Aprendizagem em Redes Horizontais do Elo Varejista do Agronegócio: do Nível Individual ao Interorganizacional». Doctoral Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, School of Management, Porto Alegre, Brazil. [ Links ]

ETZIONI, A. A. (1964), Modern Organizations. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [ Links ]

FIANI, R. (2002), Teoria dos Custos de Transação. In D. Kupfer; L. Hasenclever, Organização Industrial. 2.ª ed., Campus, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

FRYXELL, G. E.; DOOLEY, R. S. & VRYZA, M. (2002), «After the ink dries: the interaction of trust and control in US-based international joint ventures». Journal of Management Studies, 39(6). [ Links ]

GRADDY, E. & CHEN, B. (2006), «Influences on the size and scope of networks for social service delivery». Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(4), pp. 533-552. [ Links ]

GRANOVETTER, M. (1994), «Business Groups». In N. J. Smelser and R. Swedberg (Eds.). The Handbook of Economic Sociology. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., pp. 453-475. [ Links ]

GRONBJERG, K. A. (1993), Understanding Nonprofit Funding: Managing Revenues in Social Services and Community Development Organizations. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. [ Links ]

GULATI, R. (1995), «Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances». Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), pp. 85-112. [ Links ]

HAAHTI, A. & YAVAS, U. (2004), «A multi-attribute approach to understanding image of a theme park: The case of Santa Park in Lapland». European Business Review, 16(4), pp. 390-397. [ Links ]

HANDLEY, K.; STURDY, A.; FINCHAM, R. & CLARK, T. A. R. (2006), «Within and beyond communities of practice: making sense of learning through participation, identity and practice». Journal of Management Studies, 43(3), pp. 641-653. [ Links ]

HANSEN, M. T. (1999), «The search-transfer problem: the role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits». Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, pp. 82-111. [ Links ]

HITT, M.; LEVITAS, E.; ARREGLE, J. & BORZA, A. (2000), «Partner selection in emerging and developed market contexts: resource-based and organizational learning perspectives». Academy of Management Journal, 43, pp. 449-467. [ Links ]

IRELAND, R. D. & WEBB, J. W. (2007), «A cross-disciplinary exploration of entrepreneurship research». Journal of Management, 33, pp. 891-927. [ Links ]

JARILLO, J. C. (1988), «On strategic networks». Strategic Management Journal, 9(1), pp. 31-41. [ Links ]

KOGUT, B. (1988), «Joint-ventures: theoretical and empirical perspectives». Strategic Management Journal, 9(4), pp. 312-332. [ Links ]

KOZA, M. P. & LEWIN, A. Y. (2000), «Managing partnerships and strategic alliances: raising the odds of success». European Management Journal, 18, pp. 146-151. [ Links ]

LARSON, R.; BENGTSSON, L.; HENRIKSSON, K. & SPARKS, J. (1988), «The interorganizational learning dilemma: collective knowledge development in strategic alliances». Organizations Science, 9(3), pp. 285-305. [ Links ]

LAWRENCE, T. B.; WICKINS, D. & PHILLIPS, N. (1997), «Managing legitimacy in ecotourism». Tourism Management,18(5), pp. 307-316. [ Links ]

LIMA, P. E. S. (2007), «Redes Interorganizacionais: Uma Análise das Razões de Saída das Empresas Associadas». Master Dissertation, Federal University of Santa Maria, RS, Brazil. [ Links ]

LIN, Z. J.; YANG, H. & ARYA, B. (2009), «Alliance partners and firm performance: resource complementarity and status association». Strategic Management Journal, 30(9), pp. 921-940. [ Links ]

MUTHUSAMY, S. K. & WHITE, M, (2005), «Learning and knowledge transfer in strategic alliances: a social exchange view». Organization Studies, 26(3), pp. 415-441. [ Links ]

OLIVER, C. (1990), «Determinants of interorganizational relationships: integration and future directions». Academy of Management Review, 15(2), pp. 241-265. [ Links ]

OLSON, M. (1971), The Logic of the Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. President and Fellows of Harvard College. p.185. [ Links ]

OLSON, M. (1999), A Lógica da Ação Coletiva: Os Benefícios Públicos e uma Teoria dos Grupos Sociais. EDUSP, São Paulo. [ Links ]

PARAST, M. M. & DIGMAN, L. A. (2008), «Learning: the interface of quality management and strategic alliances». International Journal of Production Economics, 114(2), pp. 820-829. [ Links ]

PARDINI, D. J.; SANTOS, R. V. & GONÇALVES, C. A. (2006), «A dinâmica da aprendizagem intra e interorganizacional:perspectivas em estratégias cooperativas e competitivas utilizando as tipologias de exploration e exploitation». Revista BNDES Setorial, 12, pp.134-150. [ Links ]

PARK, S. H. & UNGSON, G. R. (2001), «Interfirm rivalry and managerial complexity: a conceptual framework of alliance failure». Organization Science, 12(1), pp. 37-53. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, B. A. D. (2005), «Estruturação de Relacionamentos Horizontais em Rede». Doctor Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, School of Management, Porto Alegre, Brazil. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, B. A. D. & PEDROZO, E. A. (2004), «O outro lado da cooperação: uma análise dos problemas na gestão das redes interorganizacionais». In Redes de Cooperação: Uma Nova Organização de Pequenas e Médias Empresas no Rio Grande do Sul. FEE, Porto Alegre. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, B. A. D.; VENTURINI, J. C.; WEGNER, D. & BRAGA, A. L. (2010), «Desistência da cooperação e encerramento de Redes Interorganizacionais: em que momento essas abordagens se encontram?». RAI – Revista de Administração e Inovação, 7(1), pp. 62-83. [ Links ]

PESÄMAA, O. (2007), «Development of Relationships in Interorganizational Networks: Studies in the Tourism and Construction Industries». Doctor Thesis, Luleå University of Technology, Strömsund, Sweden. [ Links ]

PESÄMAA, O.; HAIR, J. F. & JONSSON-KVIST, A. K. (2007), «When collaboration is difficult: the impact of dependencies and lack of suppliers on small and medium sized firms in a remote area». World Journal of Tourism Small Business Management, 1, pp. 6-21. [ Links ]

PFEFFER, J. & SALANCIK, G. (1978), The external control of organizations: a resource dependence perspective. Harper & Row, New York. [ Links ]

PROVAN, K. G.; KENIS, P. & HUMAN, S. E. (2008), «Legitimacy building in organizational networks». In B. Blomgren and R. OLeary, (Eds.), Big Ideas in Collaborative Public Management. M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY, pp. 121-137. [ Links ]

PYKA, A. & KÜPPERS, G. (2002), Innovation Networks. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

REICHSTEIN, T. & SALTER, A. J. (2006), «Investigating the sources of process innovation among UK manufacturing firms». Industrial and Corporate Change, 15(4), pp. 653-682. [ Links ]

SADOWSKI, B. & DUYSTERS, G. (2008), «Strategic technology alliance termination: an empirical investigation». Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 25, pp. 305- 320. [ Links ]

SCHERER, F. O. (2007), «Limites, Inovação e Desenvolvimento nos Relacionamentos de Redes de Pequenas Empresas no Rio Grande do Sul». Master Diseertation, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, School of Management, Porto Alegre, Brazil. [ Links ]

SYDOW, J. (2006), «Management von Netzwergkorganisationen – Zum Stand der Forschung». In J. Sydow (Org.), Management von Netzwergkorganisationen. Gabler, Weisbaden, pp. 387-472. [ Links ]

TOIGO, T. & ALBA, G. R. (2010), «Programa Redes de Cooperação do estado do Rio Grande do Sul: perfil das redes de empresas acompanhadas pela Universidade de Caxias do Sul». XIII Semead – Seminários em Administração. Anais. EDUSP, São Paulo. [ Links ]

TIWANA, A. (2008), «Do bridging ties complement strong ties? An empirical examination of alliance ambidexterity». Strategic Management Journal, 29, pp. 251-278. [ Links ]

TSANG, E. W. K. (2002), «Acquiring knowledge by foreign partners from international joint ventures in a transition economy: learning-by-doing and learning myopia». Strategic Management Journal, 23, pp. 835-854. [ Links ]

UZZI, B. (1996), «The sources and consequences of embeddedness for the economic performance of organizations: the network effect». American Sociological Review, 61, pp. 674-698. [ Links ]

VAN SLYKE, D. M. (2007), «Agents or stewards: using theory to understand the government nonprofit social service contracting relationship». Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17(2), pp. 157-187. [ Links ]

VENTURINI, J. C. (2008), «Assimetria de Informação em Redes de Empresas Horizontais: Um Estudo das Diferentes Percepções de Seus Atores». Master Dissertation, Federal University of Santa Maria, RS, Brazil. [ Links ]

VERSCHOORE, J. R. & BALESTRIN, A. (2008), «Fatores relevantes para o estabelecimento de redes de cooperação entre empresas do Rio Grande do Sul». Revista de Administração Contemporânea (RAC), 12(4), oct./dec., pp. 1043-1069. [ Links ]

WEGNER, D. (2011), «Governança, Gestão e Capital Social em Redes Interorganizacionais de Empresas: Uma Análise de Suas Relações com o Desempenho das Empresas Participantes». Doctor Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, School of Management, Porto Alegre, Brazil. [ Links ]

WEGNER, D. & PADULA, A. D. (2010), «Governance and management of horizontal business networks: an analysis of retail networks in Germany». International Journal of Business and Management, 5(12), pp. 74-88. [ Links ]

WEGNER, D.; ZEN, A. C. & ANDINO, B. F. A. (2008), «O último que sair apaga as luzes: motivos para a desistência da cooperação interorganizacional e o encerramento de redes de empresas». XI SEMEAD – Seminário de Administração. [ Links ]

WESTERLUND, M. & RAJALA, R. (2010), «Learning and innovation in inter-organizational network collaboration». Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 25(6), pp. 435-442. [ Links ]

WILLIAMSON, O. E. (1975), Market and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications». Free Press, New York. [ Links ]

WILLIAMSON, O. E. (1985), The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. Free Press, New York. [ Links ]

YAYAVARAM, S. & AHUJA, G. (2008), «Decomposability in knowledge structures and its impact on the usefulness of inventions and knowledge-base malleability». Administrative Science Quarterly, 53, pp. 333-362. [ Links ]