Introduction

Health safety has gained special prominence due to the worrying data that have been revealed. High safety standards are not achieved without the involvement of nurse managers. Recognizing the importance of the relationship between management and client safety, it is important to know which areas nurse managers privilege in the performance of their function to promote safety in the services for which they are responsible. By seeking to know the respondents' focus of attention, we can better understand their performance. Given that client safety is intrinsically linked to nurse safety, it seemed essential to us to know, in addition to the priority areas of client safety, those of nurse safety in a hospital service from the nurse managers’ point of view.

1. Theoretical framework

The publication of the report “To err is human: building a health care system” by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 2000 promoted greater attention to health safety by revealing the high number of deaths resulting from clinical errors considered preventable, and the obvious problems of systems that aim to avoid them (Institute of Medicine, 2000). Given the impact of these data, in 2004 the World Health Organization (WHO) established the World Patient Safety Alliance, renamed as WHO Patient Safety in 2009, to coordinate and accelerate global efforts to improve safety (World Health Organization, 2013).

Still, current data available show that one in ten clients is subject to health errors, of which at least 50% are considered preventable (Jha et al., 2013; World Health Organization, 2017). These errors represent billions. € 15 million in damage to healthcare systems worldwide and 15% of hospital activity and funding (Slawomirski, Auraaen, & Klazinga, 2017).

Improving the quality and safety of care is a common focus for managers, health professionals, policy makers and health service users (Schenk, Bryant, Van Son, & Odom-Maryon, 2018). But despite the continued efforts to improve safety, health damage persists (Institute for Patient and Family Centered Care, 2017; National Patient Safety Foundation, 2015; Schenk et al., 2018).

Scientific evidence on the relationship between nurse manager performance and client outcomes is recent and the monitoring of client safety outcomes and their relationship with management is limited. However, they suggest evidence of a positive relationship between nursing management and improved outcomes for the client: satisfaction, decreased adverse events, and client complications (Wong & Cummings, 2007).

Studies on the performance of nurse managers regarding the safety of the care process tend to focus on nurses' leadership behaviors in relation to job satisfaction and other organizational outcomes, and have proven to influence motivation and performance of nurses (Agnew & Flin, 2014). They also reveal that they mostly involve task-oriented behaviors and relationship management rather than change (Agnew & Flin, 2014). In addition, some risk management systems have shown that nurses have difficulties in risk management and control due to resource constraints and complexity of health work (Farokhzadian, Dehghan Nayeri, & Borhani, 2015).

However, in high-risk industries, the importance of safety of managers' roles was already recognized. (Flin, 2004) It was shown that managers' performance is related to organizational commitment to safety, worker safety behaviors and the occurrence of occupational accidents (Flin, 2004).

In order to ensure the safety of health care, it is inevitable that nurse managers implement risk management methodologies, develop management strategies for service safety and bear in mind that safety is more comprehensive and complex than just client safety and that it may be dependent on nurse safety and vice versa.

Still little explored and known are the strategies and concrete measures of nurse managers to ensure the safety of both clients and professionals. Although there are already studies on client safety and occupational safety, the two areas together as a management area is not yet evident.

2. Methods

In order to know the strategies of nurse managers to ensure the safety of clients and nurses in a hospital service, a qualitative interpretative study was developed.

Respecting the ethical and legal principles, to carry out the investigation, an authorization request was made to the President of the Board of Directors of the Hospital Center under study and to the Ethics Committee. The latter responded by stating that it only pronounces when requested by the Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Hospital Center, who is responsible for authorizing these requests. The study was authorized by the latter. All procedures performed with participants respected anonymity, confidentiality and informed consent.

2.1 Sample

Participants in this study are nurse managers of a hospital in central Portugal selected for convenience because they are the most accessible. Inclusion criteria are: minimum experience of six months managing a hospital service and being in office at the time of the interview (Fortin, 2009). The sample consisted of fourteen nurse managers: eleven women and three men with average age of 55.7 years old and management experience of 16.7 years. All specialists: eight masters, one master’s student, one doctoral student and twelve with a background in management.

2.2 Data Collection Instruments

Data were collected through individual semi-structured interviews that took place between February and May 2015 in the participants' workplace with the following question: What do you usually do in the safety service? What strategies do you use as a service manager to prevent patients and nurses from harm?

2.3 Data Analysis

Content analysis was based on Bardin's methodology which comprises three phases: pre-analysis, material exploration, treatment of results and interpretation (Bardin, 2000). As an aid in coding and categorizing interviews, Atlas.ti® software was used, which facilitated the development of the results.

3. Results

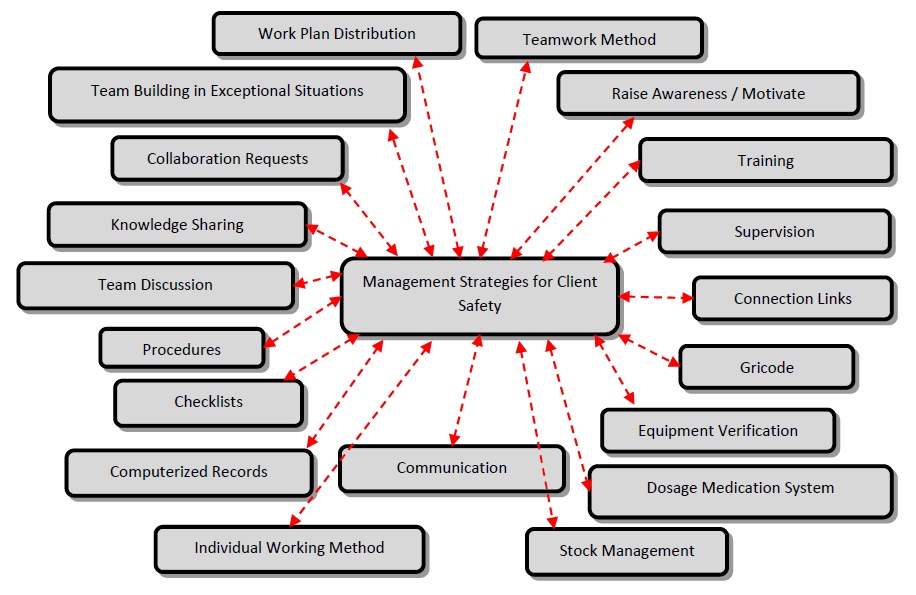

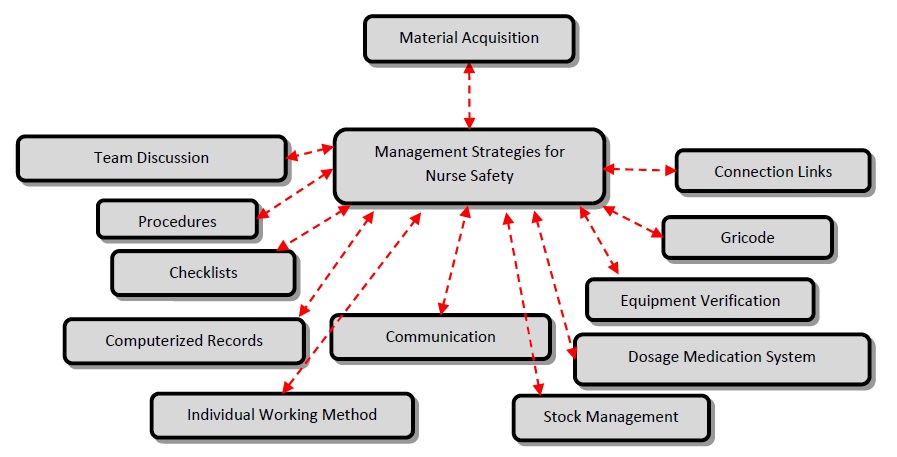

The nurse managers were asked “what strategies do you use to maintain safety in services?”. These extended their speeches and twenty categories were identified, of which nineteen relate to client safety, ten to nurse safety, of which nine are common (Figures 1 and 2).

4. Discussion

Of the nineteen categories in client safety management strategies, nine were uniquely identified for the client: Checklists, Communication, Stock Management, Unit-dose Medication System, Gricode® system, Procedures, Individual Working Method, Equipment Verification and Computerized Records (Figure 1).

The World Health Organization proposes the adoption of Checklists as one of the actions to reduce risk (Direção Geral de Saúde, 2011). A total of five interviews were identified as a safety strategy: “(…) as checklists (…) so that there could also be a systematization because then the labor intensity leads to certain trivializations. (…) ”(E5). It was also mentioned its application to the verification of equipment, materials and procedures:“ We have verification checklists since the client’s reception, in the different equipments, from instrument counting, all contributing to safety ”(E12). This work support strategy enables more methodical verification of essential safety elements.

Communication is highlighted as a strategy for safety in the speeches of five participants, namely regarding the adverse events, allowing everyone to contribute to safety: “(…) whenever there is a situation, an adverse event, make people speak about it openly so that together it can be resolved. This is fundamental!” (E4). The transmission of clinical information can lead to errors. In interviews, it is referred to as a safety instrument, both between nurse managers and team, and between professionals and client-professional. In this regard, WHO defined recommendations for safe communication between professionals, family / caregivers as well as other institutions (World Health Organization, 2007). With regard to communication for safety, there is evidence that nursing managers have a strong influence on open communication in this area (Morrow, Gustavson, & Jones, 2016).

Listed to four times, Inventory Management was referred to as a safety management strategy: “adjusting stocks (…) increasing consumption of protective gowns, aprons, all these are measures for client safety.” (E11). Inventory management is included and complies with WHO's suggested risk management action on equipment supply (Direção Geral de Saúde, 2011).

Another risk management strategy identified by WHO is the provision of a relief system and medication dispensation (Direção Geral de Saúde, 2011). The Unit-dose Medication System is a safety strategy reported by a nurse manager: “(…) we have single dose. We have several mechanisms that already allow us some safety” (E11). This work methodology allows the nurses to receive the clients’ medication identified for 24 hours, reducing the possibility of medication errors.

Participants also mentioned the implementation and use of Gricode ® System, which is a hemovigilance tool that includes three elements: client’s wristband, portable Wi-Fi terminals and software. It helps minimize errors, monitors transfusions in real time, tracks all data and optimizes the entire process, reducing time and blood consumption (Grifols, 2016).

The development and implementation of Procedures were mentioned by five participants as a strategy for client safety: “(…) we have to put everything into procedures, it is easier to do everything in the same way (…) we have everything systematized and standardized and it doesn't fail so much.” (E14). It is clear that systematization favors the prevention of errors in the client care process. Providing rapid access to protocols / policies / decision support is also a strategy advocated by WHO in risk reduction that includes procedures (Direção Geral de Saúde, 2011).

The Individual Work Method is referred to in one interviewee's speech as the most beneficial for client safety: “we hold each professional accountable for a number of clients (…) in our daily work plan, which means that if I have the information about my client, and if I take care of my client, the error is less likely to happen. If there are several people taking care of the same client, the probability of error is higher” (E11). This work method allows the organization to be done by the nurses themselves who plan, execute and evaluate, which prevents information loss, improving client safety (Carvalho & Bachion, 2009; Menezes, Priel, & Pereira, 2011).

Equipment Verification is specifically addressed by four nurse managers: “Firstly equipment safety, there is supervision and a request for team involvement to verify equipment. We are essentially talking about the care with beds, or any other material that we use as a nurse (…)”(E5), here in the sense of preservation, maintenance and verification of functionality. Accordingly, WHO recommends regular equipment audits as a risk reduction strategy (Direção Geral de Saúde, 2011).

With regard to Computerized Records, in three interviews participants referred to computerized records as a strategic element for safety: “we make electronic records, (…) they are security mechanisms, online prescription, there is no mistake, (…)” (E11), here referring to nursing records but also the online prescription system. These statements confirm that “The use of information and communication technologies in the health field is an essential element for promoting safer, more accessible and efficient ways of relating to health care.” (Ministério da Saúde, 2011, p. 3).

The client safety strategies listed represent strategies that support safe care practice, only the individual working method has to do with the human resources and the organizational service management.

Of the categories identified only the Unit-dose Medication System, Gricode ® System, is specific to client safety, the others have potential for professional safety, which was not mentioned by respondents.

Strategies for client and nurse safety

Ten categories were identified as safety strategies for clients and professionals simultaneously: Team Discussion, Knowledge Sharing, Request for Collaboration, Team Reinforcement, Work Plan Distribution, Team Working Method, Training, Awareness, Supervision, and Connection Links (Figures 1 and 2).

The Team Discussion category was mentioned by a nurse manager: “I worry about (…) discussing strategies. I try to follow up closely with the professional, observe him/her and discuss, (…) I prefer the shift, (…) to take advantage of this moment to discuss and redefine strategies (…). ”(E 10). This category reflects the need to talk about essential safety issues with the team in a constructive manner, thus contributing to a safety culture that represents one of the risk reduction actions proposed by WHO (Direção Geral de Saúde, 2011).

The Knowledge Sharing category was mentioned only in one discourse as a training strategy, albeit informal, by peers. The nurse manager, when promoting knowledge sharing among nurses, promotes training and safety.

Six nurse managers revealed the Request for Collaboration as a strategy for safety requesting support from better prepared professionals in a certain area: also to start cataloging the medicines with the new nomenclature and the colors (…). ”(E9). This strategy refers to the management of human resources and involves identifying needs and enhancing the differentiated elements and is in line with WHO's risk reduction action of ensuring adequate number and quality of professionals (Direção Geral da Saúde (2011)).

In this sense, a nurse manager mentioned the Nursing Team Reinforcement in situations where it is necessary to ensure the client and the professional’s safety: “If I have a client with invasive ventilation in the service, I reinforce that shift, (…) overtime will be proposed to ensure this more specific need for care and to have the safety of that client and all others in the service, (…) For example if I have a client who is going to be transferred, I do act in the same way in order to prevent failures in the service. ”(E11).

Work Plan Distribution is also inherent in human resource management. It was mentioned by a nurse manager who described that he develops the work plans considering the experience of nurses: “(…) I try (…), in the schedule, to never let the newly admitted colleagues work together. I always try that they are supported (…) by nurses (…) who already have more experience and who can already help make better decisions, (…) ”(E11).

The Teamwork Methodology was referenced as a strategy for safety in the discourse of three interviewees. Most studies of safety culture measurement consider teamwork, among other dimensions, to be fundamental (Singla, Kitch, Weissman, & Campbell, 2006).

Training was broadly expounded as a strategy for safety in the service, being referred to by twelve nurse managers: “(…) we try to make people available to go to trainings (…)” (E9), demonstrating here some constraint on the availability of the service to provide professionals for training, also revealed the importance of training for the maintenance and updating of knowledge. The importance of training in the prevention of occupational hazards was not overlooked, and the training of chief nurses was also addressed, but the most prominent training area was client safety: “Incentive and support for client safety service training: to nurses and other professionals (…)”(E1). Training in this area is profusely described as necessary to enable knowledge workers to safely develop their professional practice (WHO, 2011).

Awareness and motivation were mentioned in six participant speeches linking awareness and motivation to the development of a safety culture: “(…) motivates teamwork, sharing ideas about possible errors, incidents and occurrences in order to minimize / avoid the mistake. (…) I consider that a key area is safety motivation in order to minimize the occurrence of adverse events. In everything I do in the service I aim to promote safety.”(E1). From these speeches, it is clear that, “Having a motivated team creates safety.” (E14). This category is a strategy for spreading a safety culture that enables safe conduct and changes in behavior, practices and attitudes (Hopkin, 2010).

Supervision is mentioned five times in the interviews: “We are not talking about instruments but we are talking about my direct intervention as a manager, which in my day to day life contributes to the safety of the service regarding professionals and clients. I worry about continuous supervision (…)” (E10) and mentioning that it is an on-site monitoring strategy. Supervision promotes the improvement of professional competence and clinical effectiveness, and not only defends the best interests of the client but also protects the professionals. It integrates with quality and focuses on safety and risk (National Health Service, 2009).

Risk management responsibility is the responsibility of all professionals as everyone should prevent incidents and promote safety (Ramos & Trindade, 2011). However, it is the function of the health unit management body to develop risk management structures in order to be able to delegate powers at an intermediate management level. Therefore, an executive working committee should be appointed to operationalize risk management policies and form a team of interlocutors for a more dynamic and comprehensive on-site risk management intervention, closer to the reality of care delivery (Ramos & Trinity, 2011). In this sense, eight nurse managers mentioned as a management strategy the liaisons with the risk management team as a safety and support strategy in the workplace: “The liaisons with the risk committee were created. With one link per service, per area, it is easier to be aware and report. ”(E3), noting that these elements are especially prepared in this area:“ These links have made quality and safety training for the client (…). ” (E6), represented an asset in safety management.

Nurse safety strategies

As a strategy for the safety management of nurses the acquisition of professional practice support material was referenced, which allows nurses to perform their professional practice safely for themselves: “(…) acquisition of material, namely (…) tables to the dressing room because nurses spend hours in inappropriate positions. (…) Fans in rooms other than airing conditions. (…) Transfers because here there is a high turnover of clients ”(E2).

Conclusions

The results that emerge from the participants' discourses are translated into a set of attributes that allow us to understand the scope of the nurse manager to ensure safety in a hospital service.

Safety management strategies are mostly global due to the integrative safety discourse, with a predominance of mutual safety strategies of both the client and the nurse, and ten common categories were identified. This coincidence of categories of safety strategies regarding the nurse and the client confirms that they are deeply related. It is also possible to verify that the strategies are mostly supportive and practice-oriented and less about implementing change.

It is also possible to verify that the strategies for client safety outnumber the strategies for nurse safety and that some of the first could be applied to the safety of professionals, which was not mentioned by respondents.

It should also be noted that some of the strategies explained by nurse managers are in accordance with the risk reduction actions identified by WHO and other recommendations of the same body, which reflects national health policies and, consequently, the institution's guidelines aligned with the recommendations of this organization. However, a systematic safety management approach in accordance with known risk management models was not evident in any interview.

Although the lack of discourse regarding nurse safety is evident in some themes, this fact may reflect the delegation of functions in the occupational health department, although this was not mentioned.

One of the limitations of this study is that the elements of the sample belong to the same institution. Thus, we suggest this research to be replicated in other health facilities, other realities in order to verify whether there are differences of results.