Introduction

Societies are ageing fast. The ageing phenomenon and its socioeconomic impact threaten the social protection systems facing new health, social and economic issues and challenging the capacity of states to provide a fair distribution of social resources. Fighting against inequalities needs to be continually reinforced through public measures designed to address the inequalities that arise during the life trajectory, with special attention to the older people, due to their specific economic and social vulnerabilities (Fernandes and Padilha, 2012). Therefore, the population ageing is becoming a public concern and is drawing the policy makers’ attention towards creating age-based entitlement programmes (UNESCO, 2006).

Despite the numerous warnings about population ageing, policies remain a slow process and the window of opportunity to introduce meaningful changes is closing (Haverland and Marier, 2008). The genesis of ageing policies is usually linked with early pension schemes aimed to protect older workers who have lost competences and the strength to work in later life (Fernandes, 1997). However, the social agenda for old age is usually broader, especially when intended to prolong economic activity and enhance general well-being (Perek-Biazas, Ruzik and Vidovićova, 2008). This new perspective requires a comprehensive approach and a shift in parameters besides the fragmentation in order to implement active ageing policies (UNESCO, 2006). Haverland and Marier (2008) highlight that aged based policies should ensure that these are not causing an unfair burden to specific groups. It is important to create a closer cooperation among social protection systems, health care services and labour market integration (Haverland and Marier, 2008).

There are several perspectives to face the ageing policies and policy-makers need to be guided to the best intervention path. The proposal of World Health Organization entitled Active Ageing. A Policy Framework (WHO, 2002) is a potential guide for local interventions, suggesting that the responsibility for active ageing lies with the public sector, through public health programmes and social policies (Caprara et al., 2013). Defined as “the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age” (WHO, 2002), active ageing can be considered as a global goal and a political concept and it has even been converted into a mantra in ageing societies (Fernández-Ballesteros et al., 2013).

Nevertheless, the literature around the concept has triggered a debate on the lack of agreement on what it constitutes, and it is often used interchangeably with such subtle divergent notions, describing diverse views on active ageing. There are one-dimensional approaches, focused either on physical activity framework (promoting physical exercise among older people) or economic orientation and employment (promoting longer working lives). Other perspectives are multidimensional, referring to the continuous participation of older adults in different domains of life: i) both economically and socially productive activities, ii) considering activities that require physical and/or mental effort and social activities or iii) describing the paradigm as a continuous participation in the labor-market, domestic tasks, community events and leisure activities, which must be projected in individual and social terms. There are also other perspectives that supersede the mere behavioral aspect, comprising health conditions and economic circumstances (Boudiny, 2013.

In fact, from a scientific perspective, the semantic space of active ageing is an “umbrella concept” in which healthy, successful, or productive ageing is strongly related (Fernández-Ballesteros et al., 2013). Most authors in the field agree that active ageing is a multidimensional concept, embracing health, as well as physical and cognitive fitness, positively affecting and controlling social relationships and engagement, but that cannot simply be reduced to “healthy ageing,” rather needing to take into account protective behavioural determinants (Caprara et al., 2013). The WHO proposal of active ageing emphasizes citizenship, highlighting that the comprehensive challenge of demographic ageing calls for a holistic policy response. It is towards a holistic approach, considering the several policies and factors which contribute to quality of life, physical, mental and social wellbeing (Walker, 2002).

Advocates of active ageing, as a holistic approach, entail that policy-making should address all generations, stimulating the adoption of a life-cycle approach, through an orientation that anticipates critical situations and seeks to prevent them. The life-cycle concept implies a link between institutional change and individual trajectories (Guillemard, 2008), recognizes that life experiences, organized by social relationships and societal contexts, shape how people grow old (Walker, 2005) and how they relate and interact in social context where the conditions occur for individual and collective well-being over time (UNESCO, 2006).

This comprehensive view is in accordance with the European Commission (2002) that understands that active ageing practices are related to people of all ages, contributing to greater individual and social welfare, focusing on expanding the workforce and reducing the burden of dependency. It includes life-long learning, working longer, retiring later and more gradually, and engaging in capacity-enhancing and health sustaining activities. Also OECD (2000) defines active ageing in economic terms as “the capacity of people to grow old, to lead productive lives in society; meaning that people can make flexible choices in the several activities they spend on. Finally, the active ageing practices should be based on Human Rights recognition and on the principles established by the United Nations: independence, participation, dignity, care and self-fulfillment (WHO, 2002).

Although there is not a consensual definition of active ageing, Fernández-Ballesteros et al. (2013) identified a set of fields that it holds: low probability of illness and disability, high physical fitness, high cognitive functioning, positive mood and coping with stress, and being engaged with life. Fonseca (2014) argues that there is no single way to achieve active ageing. Unlike the simple pattern of normal ageing, active ageing requires from the individual a certain “life style” that, as the name suggests, should be “active”, looking to improve the individual’s functioning and performance, enabling the development and psychological well-being.

Furthermore, active ageing has not achieved a prominent position in policy agendas of European countries. According to UNESCO (2006), the policy commitment is of more rhetorical than practical value and the governance resources dedicated to developing active ageing policies are modest. This may be due to the fact that what seems clear to theoretical researchers is often imperceptible to policy makers and local interveners, being difficult to render the paradigm practical and feasible. In practical terms, the lack of instruments able to standardize the programmes analysis and evaluation jeopardizes the perception of the quality of ageing policies. Although literature begins to show ways of measuring active aging either in countries, such as active ageing index (Active Ageing Index Home, 2017), or focused on the individual, measuring the contributions of older persons to their own well-being (of their families and other people), categorizing individuals and define an active aging phenotype, or analysing individual characteristics, such as UJACAS scale (Rantanen et al., 2019), there are no tools to apply and guide social policy makers.

Taking these challenges into account, converting active ageing into a dynamic concept by creating a friendly climate for different subgroups within society, including the frail and dependent, is an ongoing challenge (Boudiny, 2013. At the same time, it is important to create methods to assess and guide public policies in order to the active ageing approach, i.e. useful techniques to help policy makers to improve their local measures for ageing according to supranational guidelines. It can be done through the use of comparative methods of different ageing programmes/ policies/ organisations and territorial units. However, the literature has no objective models to perform these comparative practices.

In this article we are using the holistic approach of active ageing by WHO to define the core contents and characteristics that ageing policies should contain. It requires active ageing actions, knowledge based in all levels, from national to local levels and reverse. Our approach is focused on local intervention where policies are implemented for older people. Generally, local government has a unique position in creating a sustainable environment for older people. The role of local authorities is taking the lead in improving social participation and ensuring a positive public policy context (Ozanne, Biggs and Kurowski, 2014). Local and regional actors are at the forefront in the opportunity for active ageing to capitalize since they will be able to understand and respond to the specific challenges in their communities. Furthermore, the local level provides many of the most essential resources that support older people to remain active in their communities (European Commission, 2011).

The main objective of this study is to create an instrument capable of being used to evaluate, analyse and compare the existing local policies addressed to the older population, based on the active ageing archetyp, according to the heterogeneity of the populations and the multidimensionality of intervention requirements. The instrument will aim to evaluate if local-level ageing policies are close to or distant to the paradigm of active ageing. In particular, the proposed instrument may be beneficial to researchers in the ageing thematic, stakeholders interested in local policies and to the active ageing concept, and policy makers. The quantitative evaluation and comparison of programmes/ policies will allow to identify age-friendly communities and good practices, which can be replicated elsewhere. The instrument should be characterized as a technique to support decision-making and policy making processes, since it already incorporates i) ideas and supranational recommendations, ii) strategies for the general organizational policies formulation, iii) results of existing ageing policies studies, and vi) older adults’ views. Thus, the theoretical support of the research is active ageing and the practical focus is on local policies directed to population ageing.

Methods

To achieve the objective, the research protocol was designed in order to create an instrument and confirm if expert researchers in the field agreed with the conceptual content and instrument building. An instrument was built to be used at communities as a standardized method to assess local policies directed to older people. For the content and building validation we applied the DELPHI method (Gracht, 2012), since it is considered a participatory practice that incorporates experts’ views, allows the validation (relevance and clarity) of the instrument items and aims to obtain agreement between members of group of experts, until consensus. The use of the DELPHI method to get a consensus among a group of experts in the ageing field, was also achieved to minimize the subjectivity of the content that could be imposed by the research team.

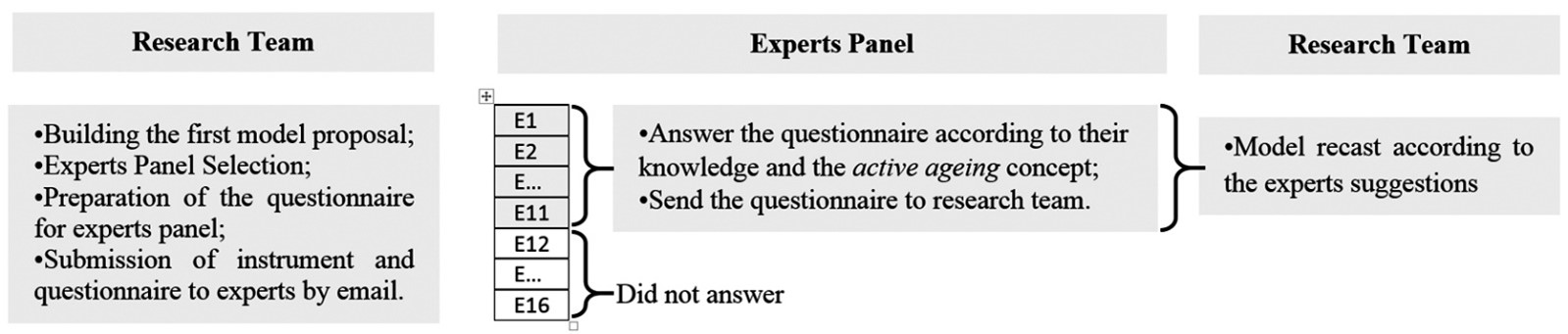

The methodological plan (Frame I) involved the following procedures: i) building the first model proposal, ii) selecting the expert panel, iii) interaction between research team and experts panel through a questionnaire, iv) consensus definition, v) statistical analysis and vi) model reformulation. Since the first draft of the model was sent to experts in the first round and the items that did not reach consensus were eliminated, we have just performed a single round.

Building the first instrument proposal

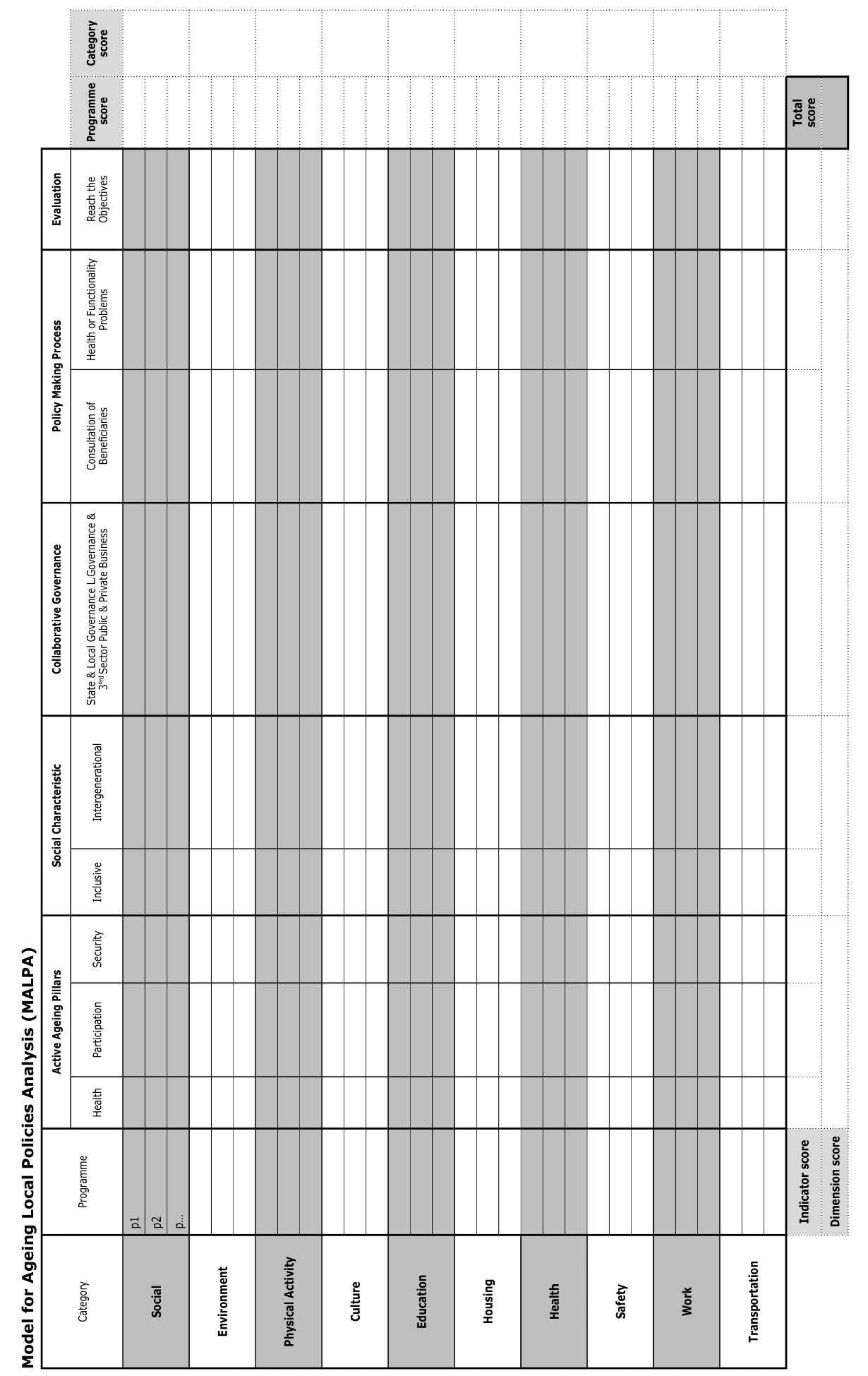

The instrument consists of: i) categories, which are able to include the different programmes that can be created at local level; ii) analytical dimensions and, within them, indicators selected according to the strength of the scientific evidence of the multidisciplinary paradigm; and iii) a classification system for the programmes under analysis.

According to the active ageing determinants (WHO, 2002) and the areas of ageing friendly cities (WHO, 2007), we selected the following categories: Social, Health, Work, Environment (referred in both documents), Culture (also inherent in both), Housing, Transportation (two areas of ageing friendly environments which were contemplated in the active ageing determinant: physical environment), Physical Activity (related to the active ageing determinant: behavioural determinants and with the area of ageing friendly cities: social participation) and Safety (considering the need to create instruments able to protect the most vulnerable and fragile groups, according to Santos et al. (2013), ensuring all the security forms: physical, psychological and economic).

The dimensions and indicators were selected taking into account the use of criteria corresponding to major components and characteristics of active ageing framework. We started to consider the dimension Active Ageing Pillars, consisting of indicators: Health, Participation and Security. The second dimension, Social Characteristic, was proposed in an attempt to evaluate whether the programmes are distant or near ageism, through the indicators: inclusive, segregationist and intergenerational. The third dimension, Collaborative Governance, was identified as a promising element in the active ageing policies and covers indicators according to the possibilities of generating partnerships between the institutions / organizations: between the State and Local Government, between Local Government and the Third Sector and/or between the Public Sector and the Private Sector. This dimension was selected since, due to the demographic challenges, the State becomes unable to meet the population’s needs and a part of welfare provision is delegated to the civil society. Ageing policies become local accountability involving all public and private bodies with multiple actors, on the governance level, which refers to the overlapping and complex relationships between players outside the political arena (Cardim et al., 2011; Davoudi et al., 2008). In practice, the community governance model establishes links between several departments of government: local, regional, national and supranational. In turn, each of these figures creates horizontal relationships with other branches of government, public services, private companies, NGOs and interest groups. The model maintains a strong role of the local government as a coordinator, which requires leadership by adopting a holistic work goal (Stoker, 2011).

The fourth dimension was called Policy Making Process and it was proposed to be evaluated through three indicators. i) Includes/Does not include, Consults/ Does not consult or Considers/Does not consider the older adults’ views in the three stages of the process: design, implementation and evaluation. This dimension was selected due to the fact that, although ageing policies should take into account the views of stakeholders/beneficiaries in setting priorities (establishing mechanisms for consulting older people and their representatives, since it is an important element of the best practices). Usually, older people are routinely ignored and not asked to rate the desirability and usefulness of the services provided to them (O’Shea, 2006). ii) Inclusion/Exclusion of older people with health or mobility problems; since people exclude the fragile from the active ageing, there is a need to develop a comprehensive strategy that includes the most vulnerable and less active (Bowling, 2008; O’Shea, 2006). iii) Top-down or bottom-up, considering the discussion about governance processes, which can differ between top-down approaches, focused on local authority leadership and programmed guidelines for age-friendliness; and bottom-up approaches, concentrated on simplifying older people’s participation, empowering them and and involving them in the neighbourhood and community (Ozanne, Biggs and Kurowski, 2014).

The last dimension was the innovation, in the attempt to evaluate if programmes are innovative or not innovative. This dimension was proposed since, in the Portuguese example, in general, ageing policies are incipient, inflexible, stigmatized and inadequate in responding to needs, requiring innovation (Bárrios and Fernandes, 2014).

To evaluate the policies/programmes, considering the positive and negative practices in relation to the proximity or remoteness of the active ageing strategy, we defined two qualitative references: (+) meaning a positive and (-) meaning a negative point.

Experts panel

The experts panel consisted of a multidisciplinary team of 11 Portuguese researchers and specialists in the population ageing thematic, with different specializations (Sociology, Economics, Social Work, Psychology, Architecture, Physical Activity, Occupational Therapy, Medicine and Physiotherapy), and from different work areas that the subject requires (Labor, Social Security and Financial Resources, Public Policies of Ageing, Social Services, Psychological Aspects of Ageing, Ageing Perceptions, Urban Planning, Transport, Security and Housing, Physical Activity, Culture, Education and Health). Experts were selected using the following criteria: recognized name, be a member of a University/ Research Center/Organization, work with public policies and ageing.

Interaction between research team and experts panel

It was built a questionnaire geared towards experts, focused on the relevance of the categories, dimensions, indicators and classification system, as well as on the scientific quality of the terminology used. To each category/dimension/indicator/classification item was applied a relative scale, accessing the agreement, with values arranged in ascending order: 1- strongly disagree, 2 - disagree, 3 - neither agree nor disagree, 4 - agree and 5 - totally agree. The questionnaire also included the possibility to suggest a new wording of categories, dimensions, indicators and classification system, as well as the inclusion of new items.

To expedite the feedback process, the method was applied online. The first instrument and the questionnaire were mailed to each expert individually, ensuring the anonymity among the experts. In the same email experts received the information with explanations and completion instructions of the questionnaire according to their knowledge and active ageing document (WHO, 2002). It was established a deadline for the questionnaire return.

Consensus definition

The consensus measurement was previously established. It was considered that: i) the experts agree with an item if assigned a value greater than 3 in the applied scale, and ii) the consensus to an item is given if more than 80 per cent of the experts are in agreement. Therefore, 80 per cent of experts should classify each category/dimension/ indicator/rating system with 4 or 5 points to be accepted. Otherwise, it would be rejected. Consensus measurement was defined in advance because it is a controversial component of the Delphi method, but it is valuable in data analysis/interpretation (Gracht, 2012).

Statistical analysis

Once the questionnaires were received, we carried out an analysis of the results in order to determine a consensus degree among experts. The data analysis was performed using descriptive statistics, building percentages tables for the set of categories, dimensions, indicators and rating system. The suggestions made by the experts were also compiled and some of them have led to changes and improvements.

Results

Experts contribution and instrument revision

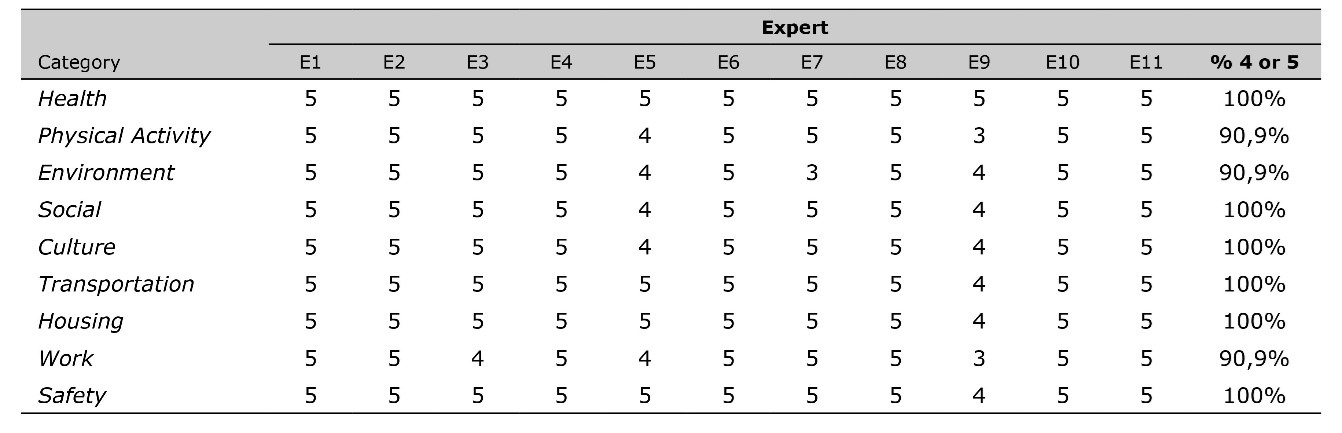

All the categories have reached the consensus (Table 1) and they were kept in the model. After analysing the experts’ suggestions, it was introduced the Education category. As a matter of fact, among the determinants of active ageing, the pursuit of education is one of the most important factors, not only because education is the key to one’s occupation but also because schooling and lifelong education influence health and all behavioural repertoires across the lifespan. So, this new category can include educational opportunities for adults through policies such as universities for the third age as well as promote learning and educational opportunities throughout adulthood and old age (Fernández-Ballesteros et al., 2012).

Programmes under evaluation should be inserted in one of the categories, according to the higher percentage of intervention área. However, a programme can be analyzed as part of other categories, if it is important to carry out a meso or macro analysis.

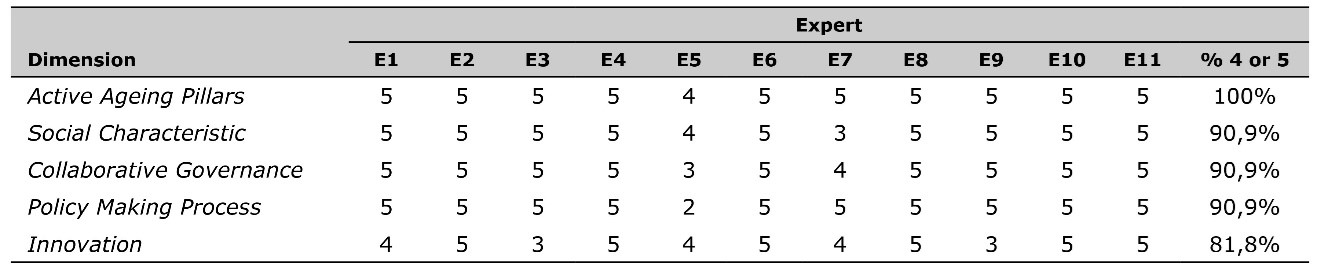

As presented in Table 2, all the dimensions have achieved a percentage of agreement between experts over 80 per cent and, therefore, a consensus. However, after analyzing the experts’ suggestions we have made two changes. The first one was the elimination of the innovation, since experts asked the meaning and context in which it is applied and the research team considered it was difficult to access it. The other was the inclusion of the evaluation in order to analyze the policy effectiveness and check if the proposed objectives were reached in results, within the active ageing promotion. This dimension is focused on effectiveness and is carried out considering the available outputs, records and data.

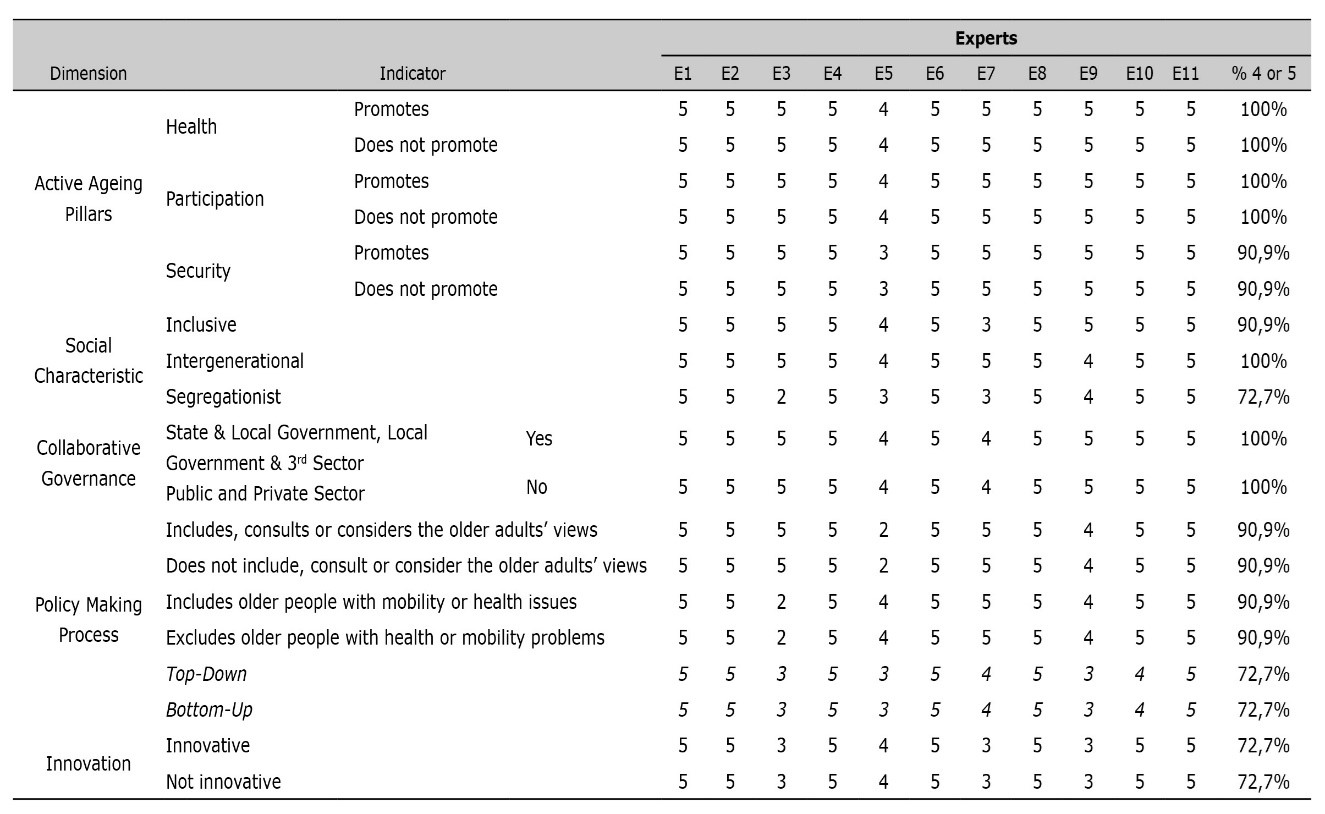

The following indicators: segregationist, top-down/bottom-up and innovative/ not innovative have only obtained 72.7 per cent agreement among the experts, having fallen short of the consensus and, consequently, were eliminated from the instrument (Table 3).

Accepting the suggestion of an expert, in the indicators: includes/ excludes older people with mobility or health issues, we substituted mobility by functionality. The functionality includes all body functions (anatomical and physiological), activities (related to task performance) and participation (inherent to the involvement of the person in “life situations”). So, functioning disorders do not only concern to physical mobility but also concerning several domains of daily living activities: falls, locomotion, physical and instrumental autonomy, cognitive and social status, among others (Fontes, Botelho and Fernandes, 2014).

Regarding the remaining indicators, they have reached a consensus and remained unaltered.

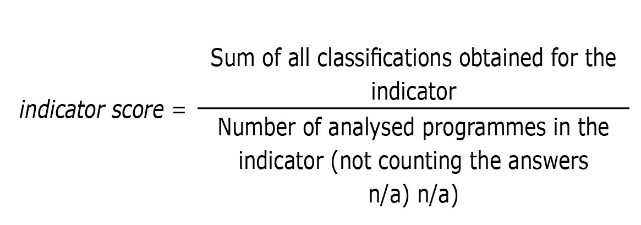

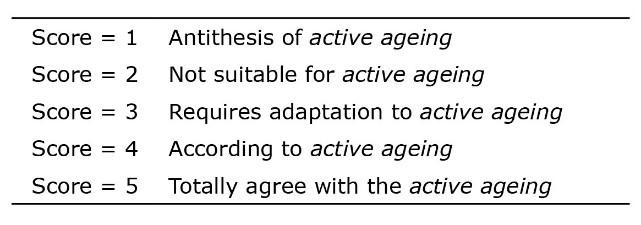

Concerning the rating system results, statistically, the indicators: top-down (+)/ bottom-up (-) had not achieved a consensus (already removed). The experts felt the need for more evaluation options. Some of them have suggested the addition of intermediate ratings to partially positive and partially negative situations, such as (+/-); others believed that a scale of 1 to 5 points would function better (because in many cases situations are not black or white, but grey). Taking into account these suggestions, the classification system was changed into a value scale in which each indicator was assigned a set of five response options, by multiple choice, arranged in order of increasing value. The option that is closer to the active ageing has the highest value (5). In turn, the distal option of the concept has the lowest value (1). It is only allowed to choose one answer. When the indicator is not appropriate to the programme under review, the option n/a (not applicable) should be chosen.

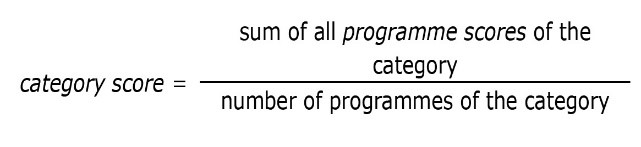

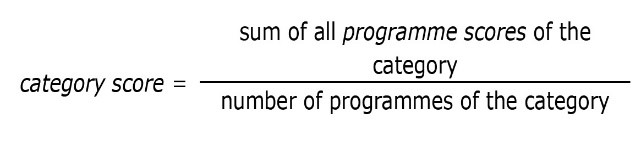

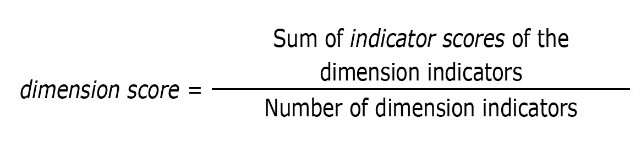

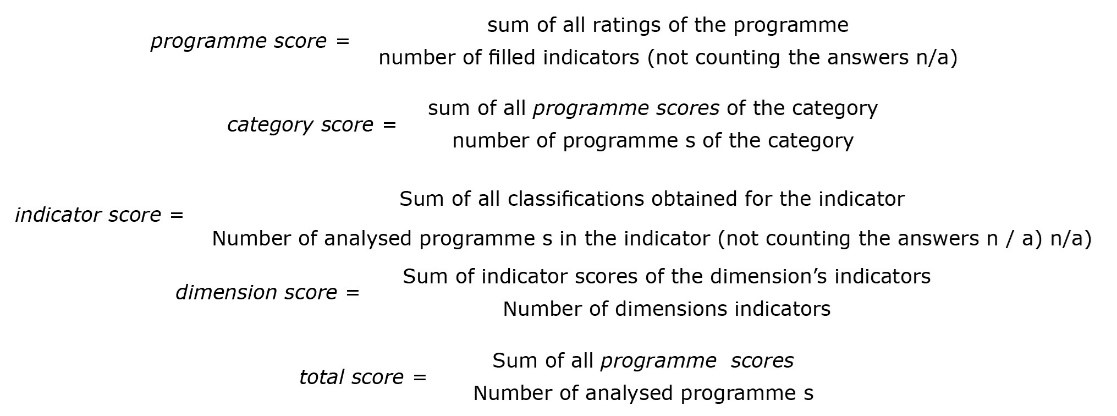

Score(s) calculation

The classification system requires the definition of scoring results obtained in the value scales for each indicator. It allows the interpretation, analysis and evaluation of each programme, in particular, or of the ageing policies, in general.

Each programme can be analysed individually through the programme score calculation, checking if it is near or far from the active ageing guidelines. Based on this result, we can identify good and bad practices. After the evaluation, the Categories, Dimension or Indicators with lower values must be consider the priority intervention sectors.

On the other hand, we can evaluate a set of programmes and explore policies in an institution/ organization/ local governance of one or more communities. This can be done through the evaluation / analysis of each policy sector calculating the score category, identifying whether policies from a certain category are fit or deviate according to the active ageing strategy.

Another way to analyse the ageing policies consists in calculating the indicator score and/ or dimension score, in order to determine in which indicators/ dimensions the policies diverte or are appropriate to the active ageing strategy.

Finally, for a more comprehensive analysis of ageing local policies in one or more institution/ organization/ community, we can determine the total score. It will allow to determine whether the ageing policies, as a whole, are close or distant from the selected paradigm. This score also enables the comparison of different communities and may encourage the sharing of practices with higher values.

The interpretation of each score may be carried out according to the following Figure 2:

The final instrument was named: Model for Ageing Local Policies Analysis (MALPA) and instructions have been created for its application (supplementary material).

MALPA application

The instrument created was already applied to compare two Portuguese communities, as a technique able to evaluate, analyse and compare local policies and resources available for older people (Bárrios, 2017), allowing to identify important results to be considered by social policies.

In the study of Bárrios, Fernandes and Fonseca (2018), MALPA was used to analyse ageing local policies in two different Portuguese municipalities in terms of sociodemographic and economic characteristics (Coruche and Oeiras). The instrument application was effective in comparing programmes and communities, at the macro and meso levels: comparing dimensions and indicators between the municipalities; and at the micro level: evaluating specific programmes, helping the development of proposals for the improvement of ageing local policies. Coruche has a total score of 3.6 and Oeiras 3.8, (both positive), the intervention category that has the lowest score in Coruche was culture (3.4) and in Oeiras was education (3.4). At the same time, it has allowed to identify 10 priorities (the lowest scores in each category) about collaborative governance, participation of older people in the policy-making process, lifelong learning, economic privation, policies for all ages, isolated and fragile groups, intergenerational interactions, safety in all policies, labour opportunities, and quality of transport network (Bárrios, Fernandes and Fonseca, 2018).

Miguel (2018) has also conducted a case study using MALPA to evaluate a specific community programme in Lisbon (Portugal) named “A avó veio trabalhar”. It was able to ascertain the positive characteristic of the project: health (5), participation (5) and collaborative governance (5). In turn, it was also possible to identify features less attractive from the point of view of active ageing: excludes older people with health or functionality problems (Health or Functionality: 2).

Conclusion

With this research we created the instrument MALPA, which is focused on evaluation, analysis and comparison of ageing local programmes, from the active ageing point of view. The MALPA enables the systematic analysis of ageing policies at local level, in order to facilitate the identification of good or best practices considering the active ageing paradigm, and recognizing the inappropriate policy actions directed to the ageing population. Through the scoring procedures we will be able to identify the intervention priorities, in order to improve, adapt or amend the measures and resources that local governance provides to population. The relevance of this study also extends to the ability to guide policy makers in the selection of programmes proposed by civil society.

The instrument can be applied by researchers, stakeholders and policy makers, has an objective character and is easy to apply even by common people, following the instructions. Its use in different communities, cities or regions allows the comparison of their ageing policies and sharing their most successful experiences.

Active ageing framework is based on a perspective able to be applied in ageing policies. Several critical researchers disagree with its application. This may be due to the fact that what seems clear to theoretical researchers is often imperceptible to policy makers and local interveners, being difficult to render the paradigm practical and feasible.

Actually this proposal, MALPA instrument, has a broader perspective, holistic and multidisciplinary, and focused on practical dimensions of communities. Recognizing that the WHO guidelines also call for individual responsibility, it should be noted that aspects related to population require other approaches and other instruments.

However, the ageing policies evaluation, analysis and comparison find problems and constraints. This is due to the complexity of the policy evaluation methodology, such as the heterogeneity in the operationalization of the model, considering the numerous configurations and functions of the applicators (Bárrios, 2017). Moreover, authors reported that the implementation and evaluation of such programmes are long term (Caprara et al., 2013). These considerations lead to the recognition that the instrument must be tested to identify any obstacles and methodological limitations. Further studies are needed to apply the instrument created, applying it in different realities and to testing its usefulness in comparative social policy.