Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Jornal Português de Gastrenterologia

versão impressa ISSN 0872-8178

J Port Gastrenterol. v.18 n.3 Lisboa maio 2011

Profilaxia da Reactivação do Vírus da Hepatite B na Terapêutica Imunosupressora em Doenças Reumáticas. Orientações para a Prática Clínica*

Joana Nunes1, Rui Tato Marinho1, João Eurico Fonseca2, José Alberto Pereira da Silva2, José Velosa1

1Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Hospital Santa Maria, Lisbon, Portugal; 2Department of Rheumatic Diseases, Hospital Santa Maria, Lisbon, Portugal.

RESUMO

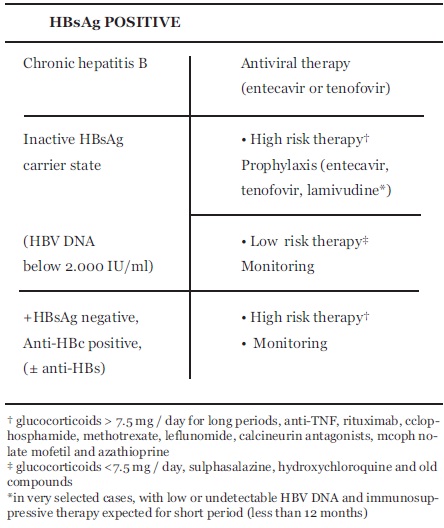

A reactivação da infecção pelo vírus da hepatite B (VHB) é uma complicação potencialmente grave da imunossupressão, que pode ser identificada e prevenida de modo eficaz. Tem-se verificado um número crescente de casos de reactivação do VHB em doentes sob imunossupressão no contexto de doenças reumáticas, como a artrite reumatóide o u o lúpus eritematoso sistémico. As recomendações nesta área devem ser individualizadas, tendo em conta dois aspectos: os esquemas imunossupressores utilizados (alto ou baixo risco de reactivação) e as diferentes fases da infecção pelo VHB, como seja a hepatite B crónica, o portador inactivo do VHB, ou mesmo a infecção oculta (por exemplo AgHBs negativo com anti-HBc positivo). Nos doentes com doenças reumáticas que vão iniciar terapêutica imunossupressora de alto risco, propomos o rastreio universal com testes serológicos da hepatite B com o antigénio de superfície do VHB (AgHBs), anticorpo anti-HBs e anti-HBc. Os doentes com hepatite B crónica (AgHBs positivo, ADN VHB l 2000 UI/ml) devem iniciar terapêutica antivírica; os portadores inactivos do VHB (AgHBs positivo, ADN VHB < 2000 UI/ml, aminotransferases normais) expostos a terapêutica imunossupressora de alto risco devem realizar igualmente profilaxia da reactivação do VHB. A profilaxia deve ser iniciada 2 a 4 semanas antes do início da terapêutica imunossupressora e mantida pelo menos durante 6 a 12 meses após a sua suspensão. Recomenda-se a utilização do entecavir ou tenofovir como antivirícos de primeira linha. Nos portadores inactivos do VHB sob terapêutica imunossupressora de baixo risco nos doentes AgHBs negativo / anti-HBc positivo (infecção a VHB no passado ou infecção oculta), a estratégia deve ser monitorização da reactivação viral através da determinação das aminotransferases e do ADN-VHB a cada 6 meses).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Doenças reumáticas, reactivação da hepatite B, imunossupressão, entecavir, tenofovir.

Prophylaxis of Hepatitis B Reactivation with Immunosuppressive Therapy in Rheumatic Diseases. Orientations for Clinical Practice

ABSTRACT

Reactivation of infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a potentially serious complication of immunosuppression, which should be identified and efficiently prevented. There have been an increasing number of cases of HBV reactivation in patients receiving immunosuppression in the context of rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. The recommendations in this area should be individualized taking into account two aspects: immunosuppressive regimens used (high or low risk of reactivation) and the different stages of HBV infection: chronic hepatitis B, inactive HBV carrier, occult hepatitis B infection defined by HB surface antigen (HBsAg) negative and antibody anti-HB core (anti-HBc) positive. In patients with rheumatic diseases that will start high risk immunosuppressive drugs, we propose a universal screening with serological tests for hepatitis B (HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc). Patients with chronic hepatitis B (HBsAg positive, HBV DNA l 2000 IU / ml) should initiate antiviral therapy. Inactive HBV carriers (HBsAg positive, HBV DNA < 2000 IU / ml, normal aminotransferases) exposed to high risk immunosuppressive therapy should undergo prophylaxis of HBV reactivation. Prophylaxis should be started 2 to 4 weeks before the beginning of immunosuppressive therapy and maintained for at least 6 to 12 months after its suspension. It is recommended to use entecavir or tenofovir as first line antiviral agents. In inactive HBsAg carriers under low-risk immunosuppressive therapy and patients with HBsAg negative / anti-HBc positive (HBV infection in the past or occult inspection), the strategy should be monitoring of viral reactivation with aminotransferases and HBV DNA determination in every 6 months.

KEYWORDS: Rheumatic diseases, hepatitis B reactivation, immunosuppression, entecavir, tenofovir.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) chronic infection is the leading cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the world 1. It is estimated that almost one third of the world population has been infected with the virus and about 350 million people are chronically infected2. In Portugal, about 1% of the population has a chronic carrier of HBsAg3. Hepatitis B infection is easily prevented by vaccination4.

HBV infection is a heterogeneous disease with distinct phases, depending on age of infection, viral replication, immune response against the virus and liver damage. The evolution for chronicity is unusual in adults, with more than 99% clearing effectively the virus5. However, in most of these patients viral particles remain in the nucleus of the hepatocytes, and may be used as copies for viral replication under some circumstances, like immunosuppression6. If not detected and treated, viral reactivation can be severe and sometimes fatal. Given the increasing use of immunosuppressant, the potential serious effects of HBV reactivation and efficacy of prophylaxis, it is important to identify patients at risk and implement appropriate measures.

The aim of this paper is to review hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients under immunosuppression therapy for rheumatic diseases and to porpose prophylactic measures. This was made considering recent data available in the literature of rheumatic diseases and taking into account the experience obtained in other areas where there is more extensive knowledge on this subject, like hematology and oncology7,8.

HEPATITIS B VIRUS INFECTION

1) The natural stages of chronic hepatitis B virus infection

The natural history of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection is determined by the interplay between the virus and the host immune response9,10. According to this, it is possible to distinguish five phases:

- immune tolerant phase. The immune system is not reacting against the virus. The virus replicates freely, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) is positive, with very high levels of HBV DNA, (more than 108 IU/ml) but there is no liver damage and aminotransferases are normal.

- immune reactive phase. The immune system controls the virus. Low serum HBV DNA levels are present, with increased or fluctuating levels of aminotransferases and moderate to severe liver necroinflammation.

- inactive HBV carrier phase. Represents immunological control of the infection and is characterized by very low or undetectable serum HBV DNA levels, antibody against HBeAg (anti-HBe) positivity and normal aminotransferases. These patients have a very low risk of cirrhosis or HCC. HBV DNA is less than 2 000 IU/mL.

- HBeAg negative CHB phase. This represents a later phase in the natural history of CHB infection, with the development of HBeAg negative variants. It is characterized by active hepatitis, with fluctuating levels of HBV DNA and aminotransferases.

- HBsAg negative phase. This is the closest to cure of CHB infection and it is characterized by the presence of antibody against HBcAg (anti-HBc) with or without antibody against HBsAg (anti-HBs). In these patients, low-level of HBV replication occurs in the liver, but HBV DNA is generally not detectable in the serum (termed occult HBV infection)11. This occurs because during viral replication copies of covalently closed and circular DNA (cccDNA) are produced, and these remain in the nucleus of the hepatocytes, integrated in host DNA. It is considered that all HBsAg negative anti-HBc positive individuals are potential HBV occult carriers. Although they have generally an excellent prognosis, an increasing number of viral reactivation cases have been reported in concomitantly immunossuppressed patients12 or in the setting of organ transplants13.

This late phase is indistinguishable from the recovery of an acute hepatitis B.

2) Diagnostic markers in hepatitis B virus infection

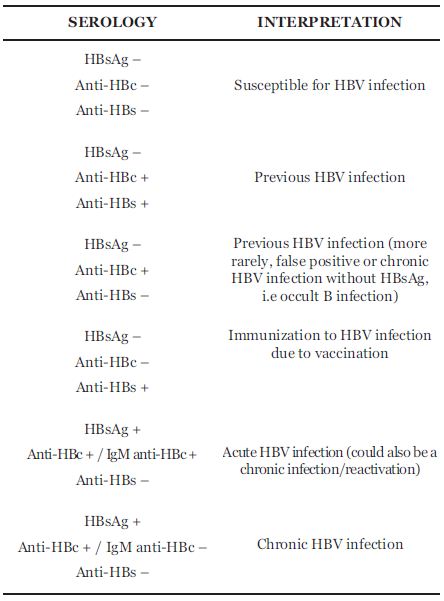

The diagnosis of HBV infection typically is based on the evaluation of serologic markers of HBV infection. The serologic markers allow the distinction between active (including acute or chronic hepatitis B) and past infection. It also identifies vaccinated and susceptible persons for acquiring HBV infection (Table 1).

Table 1. Interpretation of hepatitis B virus serology

3) Definitions and diagnostic criteria used in HBV infection

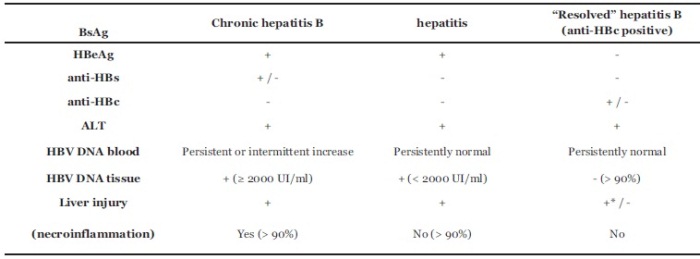

In clinical practice, it is useful to classify patients with the following definitions: chronic hepatitis B, inactive HBsAg carrier and resolved hepatitis B14,15.

- chronic hepatitis B (active carrier of HBV) is defined as the presence of HBsAg (two determinations, 6 months apart) with or without concomitant HBeAg and HBV DNA l 2000 IU/ml (the immune reactive phase and the HBeAg negative CHB phase). This condition is characterized by chronic necroinflammatory liver disease (elevated ALT and histological lesions in liver biopsy) related with persistent viral replication. Chronic hepatitis B can be subdivided into HBe-positive chronic hepatitis B and HBe-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatitis B e-negative chronic hepatitis B is the most common, representing nowadays about 70 to 80% of chronic hepatitis16. Therapy for HBV is indicated. When HBV DNA levels are above 2000 IU/ml and/or the serum ATL levels are above the upper limit of normal and liver biopsy shows moderate to severe active necroinflammation and/or fibrosis.

- inactive HBsAg carrier is defined as the presence of HBsAg without HBeAg, normal aminotransferases and low viral load (< 2000 UI/ml). These patients have persistent liver HBV infection without significant ongoing necroinflammatory disease (they have HBV infection without "hepatitis"). There is no indication for therapy in this group but they may be candidates for prophylaxis of HBV reactivation.

- resolved hepatitis B (the HBsAg-negative phase described above) is characterized by previous history of acute or chronic hepatitis B or the presence of anti-HBc (with or without anti-HBs). HBV DNA is usually undetectable in the serum, but may be detectable in hepatocytes. It is considered as potential occult hepatitis B infection (OBI). These concepts are outlined in table 2.

Table 2. Definition and diagnostic criteria of chronic hepatitis B, inactive HBsAg carrier state and resolved hepatitis B infection/ occult B infection

HEPATITIS B INFECTION AND IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE THERAPY

1) The mechanism of HBV reactivation

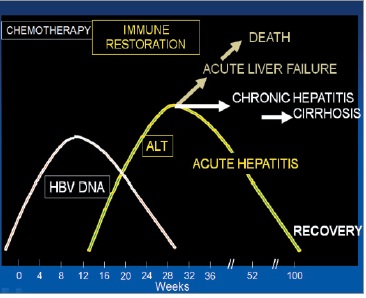

The immunosuppressive schemes used in several diseases and in the transplantation field may influence HBV infection, accelerating the course of liver disease or reactivating it17. In most situations, reactivation of hepatitis B leads to an asymptomatic flare, but cases of decompensated liver disease, fulminant hepatitis and death have been described12,18.

Liver damage in HBV reactivation occurs in two main occasions (Fig. 1): massive viral replication during immunosuppression or in the immune restoration phase, immediately after the withdrawal of immunosuppression, which is characterized by an enhanced host immune response against HBV infected hepatocytes. This latter mechanism is the most implicated in liver damage, which can vary from a mild hepatitis to hepatic failure and death.

Fig. 1. Hepatitis B reactivation and immunosuppressive therapy

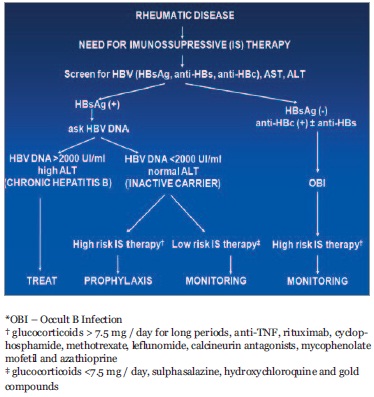

Fig. 2. Algorithm to manage HBV infected patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy for rheumatic diseases

The rate of reactivation is higher in the context of hemato-oncological diseases (14 to 70%)18,19. HBV reactivation can also occur in patients receiving chemotherapy for solid organs20, and this complication can become more frequent due to the increasingly aggressive immunosuppressive regimens.

Severe cases of hepatitis flares have been described during treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis21,22 and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) 23,24 with chronic HBV infection. With the widespread use of this class of drugs, more cases of reactivation of HBV infection in inactive HBsAg carriers25 and also in individuals with occult infection26 have been reported.The long term follow-up of HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive patients treated with anti-TNF suggests that the reactivation rate is low. In fact, in a cohort of 72 patients followed for 43.5 ± 21.3 months no reactivation has occurred27. The issue of HBV reactivation has been included in review articles and consensus on the management of IBD patients28,29. The evidence seems to support that if HBV infection is properly diagnosed and treatment or prophylaxis is adequately begun the use of anti-TNF in hepatitis B patients is safe30-32.

Other biological therapies, particularly rituximab (anti- CD20)12,33-35 and alemtuzumab (anti-CD52)36 have been involved in cases of HBV reactivation of HBsAg positive individuals and of HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive patients with hemato-oncologic diseases. The risk of HBV reactivation with rituximab is higher when it is used in combination with chemotherapy, but it can occur with rituximab alone35. Reactivation of HBV seems to be less frequent in rheumatic patients treated with rituximab but same cases have been reported37.

There are no reported cases of HBV reactivation in the context of the use of abatacept, anakinra and tocilizumab.

Apart from the use of biologics attention should be also paid to the use of other immunossuppressors for rheumatic diseases treatment. Of particular relevance is the use of moderate to high dose of corticoids for systemic lupus erythematosus management which have been clearly associated with HBV reactivation38. In addition, treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with low dose methotrexate (MTX) has been associated with fatal HBV reactivation in HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive patients and the immunological reconstruction after MTX withdrawal has been also associated with fatal HBV reactivation39-42.

Beyond the risk of a serious hepatic event, HBV reactivation associated with immunosuppression has a negative impact on their disease, delaying or hindering treatments that would be needed for remission induction or maintenance, with a significant impact on social and familiar aspects and in the quality of life of these patients.

There are some trials, including two randomized trials, showing that prophylactic therapy with lamivudine can reduce the rate of viral reactivation and mortality43-45. However, in the field of rheumatology, there are no national or international recommendations for the prophylaxis of HBV reactivation, despite some previous discussions published in the context of case reports and reviews21-28,46

2) WHO SHOULD BE SCREENED FOR HBV INFECTION?

There is no consensus on which patients should be screened before the institution of an immunosuppressive therapy. There are two main strategies: screening patients considered at high risk for HBV infection or universal screening. The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines15, recommend universal screening of all candidates for immunosuppressive therapy. Given the absence of risk factors in many patients with HBV infection, the risk of HBV reactivation and the possibility of adequate prevention, we defend that screening should be universal. Thus, and referring to patients with rheumatic disease, all patients who will start or are assumed to require immunosuppressive therapy should be screened for HBV infection.

3) HOW TO SCREEN?

The screening for HBV chronic infection should be done with the determination of HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HBs. It is further recommended that patients with negative serological tests (HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc all negative) should be vaccinated as soon as possible, preferably with a rapid scheme, consisting of four doses at 0, 1, 2 and 12 months. The patients with positive HBsAg should be evaluated for viral load (HBV DNA by Real time PCR) 47.

In vaccinated population, anti-HBs titles should be evaluated.

4) THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HBV THERAPY, PROPHYLAXIS AND MONITORING

The term therapy is reserved for treatment of patients with liver damage (chronic hepatitis B).

The term prophylaxis is used to characterize the use of antiviral agents in order to prevent viral reactivation. Prophylaxis can be performed on all individuals at risk (universal) or initiated only if evidence of reactivation, consisting in increased level of HBV DNA and / or seroreversion of HBsAg (i.e. HBsAg negative individuals that become positive) and hepatitis flare (targeted). Inactive HBsAg carriers treated with low risk immunosuppressive therapies should maintain a strategy of periodic monitoring HBV reactivation.

Monitoring is done by testing HBV DNA and aminotransferases periodically, with some authors suggesting a three to six months interval7,46. It was demonstrated that the increase of HBV DNA occurs early in the natural history of reactivation, preceding the aminotransferases flare48,49. If monitoring is the strategy, prophylaxis or therapy for HBV should be initiated as soon as there is increase in viral load.

5) WHICH RHEUMATIC PATIENTS SHOULD START THERAPY AND / OR PROPHYLAXIS OF HBV REACTIVATION?

Reactivation of HBV depends fundamentally on two issues: phase of infection (active, inactive or occult B infection) and type of immunosuppression.

- Chronic hepatitis B infection (HBsAg positive, HBV DNA B 2000 IU/ml, increased or normal ALT, necroinflammation and fibrosis on liver biopsy).

This group of patients should start antiviral therapy for hepatitis B, whether performing or not immunosuppressive therapy7,14,15. Immunosuppressive therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B under antiviral therapy is safe50.

- Inactive HBsAg carriers (HBsAg positive, HBV DNA < 2000 IU / ml, normal ALT)

In these patients, there is a risk of HBV reactivation, which is related with the type of immunosuppression used. The use of steroids in medium or high dose (> 7.5 mg / day for long periods), anti-TNF drugs, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, leflunomide, calcineurin antagonists, mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine is associated with high risk of reactivation (14 to 70%) and thus these patients should perform universal prophylaxis, regardless of viral load25. Patients receiving glucocorticoids < 7.5 mg / day, sulphasalazine, hydroxychloroquine and gold compounds are considered at low risk for HBV reactivation46. In these patients we recommend monitoring of HBV DNA, ALT, AST and HBsAg every 6 months, starting prophylaxis / therapy in the case of HBV reactivation (HBV DNA l 2000 IU / ml and / or seroreversion of HBsAg).

- Occult hepatitis B virus infection

The management of occult B hepatitis virus infection is still a controversial issue. There are not enough data in the literature on this subgroup of patients. In two recent papers, no evidence of HBV reactivation was found in rheumatic patients treated with anti-TNF therapy and resolved hepatitis B (anti-HBc positive),27,30. Prophylaxis in this setting is not recommended. It is suggested monitoring for HBV reactivation (mainly those submitted to highly immunosuppressive treatments).

This concepts and decision algorithm is schematized in table 3.

Table 3. Treatment strategies according to HBV stage

6) WHEN TO START AND TO STOP PROPHYLAXIS?

Prophylaxis should be started 2 to 4 weeks before the beginning of immunosuppressive therapy. As already mentioned, the risk of HBV reactivation is greater after the withdrawal of immunosuppression (immune restoration period). Therefore, prophylaxis should be maintained for at least 6 to 12 months after the suspension of immunosuppressants14,15.

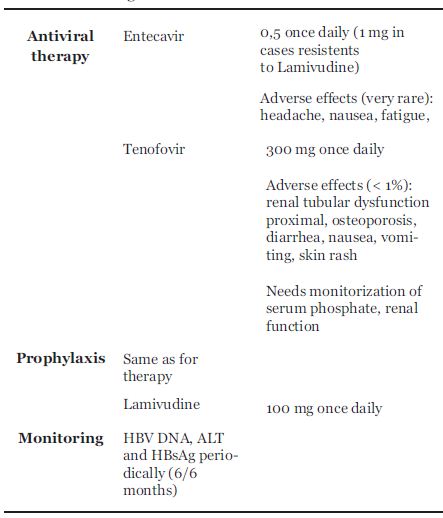

7) WHICH DRUGS TO USE?

Drugs with anti-HBV activity are based primarily on two groups: nucleoside / nucleotide analogues (NA) and pegylated interferons.

Pegylated interferons (alpha-2b or Pegintron® and alpha-2a or Pégasys®) have not only antiviral but also immunomodulador effects and may lead to acute hepatitis flares. They should not be used in this context.

The nucleoside / nucleotide drugs (NA) are orally administered (one pill a day), well tolerated and safe. There are several NA approved for the therapy of chronic hepatitis B: lamivudine and adefovir, which are first generation drugs having high levels of resistence51, and entecavir and tenofovir, with high potency and low resistance profile52. Lamivudine is an inexpensive drug, but due to its low genetic barrier, with rates of resistance as high as 20% after one year and up to 75% at five years, it is no longer recommended as first line treatment of HBV. However, most studies of prophylaxis of HBV reactivation in patients undergoing immunosuppression are with lamivudine43-45. This drug can be a valid option in selected cases, like prophylaxis in HBsAg negative / anti-HBc positive during short term immunossupression, such as the case of hematologic or oncologic disorders. Nevertheless, in patients with higher viral loads (HBV DNA above 107 IU/ml) and in those in whom the duration of immunosuppressive therapy is expected to be held for more than a year, drugs with high potency and high genetic barrier (entecavir and tenofovir) should be considered as first line15 (table 4). They have excellent resistance profiles, with a rate of resistance of 1,2% at 65 years and 0% at 3 years respectively53,54. Entecavir and tenofovir have been successfully used as prophylactic agents to avoid HBV reactivation in patients under immunosuppressive therapy55,56 or to treat hepatitis flares, in cases where prophylaxis was not done57,58.

Table 4. Stategies for hepatitis B treatment, prophylaxis and monitoring

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS:

1. Hepatitis B reactivation during immunosuppressive treatment can occur in any stage of HBV chronic infection; it can be severe and sometimes fatal due to liver failure. The withdrawal of the immunossupression is also a risk phase.

2. All patients who are candidates for immunosuppressive therapy should be screened for the status of HBV infection.

3. The screening should include ALT, HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc.

a) In patients with HBsAg positivity, viral load (HBV-DNA) should be performed. b) In patients having HBsAg negative / anti-HBc positivity (± anti-HBs) occult hepatitis B infection is a possibility.

c) Patients negative for all HBV markers should be vaccinated as soon as possible.

4. The management (whether prophylaxis or monitoring) of patients undergoing immunosuppressive with evidence of present or past HBV infection therapy is determined by the stage of HBV infection and the intensity of the immunosuppressive regimen.

5. HBsAg positive patients should be evaluated by a specialist in liver diseases to decide whether to start therapy (active carriers) or prophylaxis (inactive HBsAg carriers under high risk immunosuppressive therapies). Monitoring for HBV reactivation is indicated in inactive carriers under low risk immunosuppressive therapies and occult hepatitis B infection.

6. In HBsAg negative / anti-HBc positivity (± anti-HBs) patients, monitoring is indicated in cases of high risk immunosuppressive therapy.

7. Prophylaxis of HBV reactivation should be initiated 2 to 4 weeks before the beginning of immunosuppressive therapy and maintained 6 to 12 months after its suspension.

8. The drugs recommended for prophylaxis are nucleos(t)ide analogs like entecavir or tenofovir. Lamivudine can be used in selected cases (occult B hepatitis virus infection).

9. Monitoring HBV reactivation should be performed periodically (each 3 to 6 months) with the determination of aminotransferases and HBV DNA levels.

REFERENCES

1. Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2007;45:507-539. [ Links ]

2. Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat 2004;11:97-107. [ Links ]

3. Lecour H, Ribeiro AT, Amaral I. Prevalência do antigénio de superfície da hepatite B na população portuguesa. O Médico 1981;98:326-334. [ Links ]

4. Szmuness W, Stevens CE, Harley EJ, et al. Hepatitis B vaccine: demonstration of efficacy in a controlled clinical trial in a highrisk population in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:833-841. [ Links ]

5. Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: Special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol 2008;48:335-352. [ Links ]

6. Fong TL, Di Bisceglie AM, Gerber MA, et al. Persistence of hepatitis B virus DNA in the liver after loss of HBsAg in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 1993;18:1313-1318. [ Links ]

7. Marzano A, Angelucci E, Andreone P, et al. Prophylaxis and treatment of hepatitis B in immunocompromised patients. Dig Liver Dis 2007;39:397-408. [ Links ]

8. Artz AS, Somerfield MR, Feld JJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion: Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection Screening in Patients Receiving Cytotoxic Chemotherapy for Treatment of Malignant Diseases. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:3199-3202. [ Links ]

9. Ganem D, Prince A. Hepatitis B virus infection - natural history and clinical consequences. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1118-1129. [ Links ]

10. Carneiro de Moura M, Marinho R. Natural history and clinical manifestations of chronic hepatitis B virus. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2008;26:11-18. [ Links ]

11. Raimondo G, Pollicino T, Cacciolla I, et al. Occult hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol 2007;46:160-170. [ Links ]

12. Sung-Nan SN, Chen CH, Lee CM, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus following rituximab-based regimens: a serious complication in both HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative patients. Ann Hematol 2010;89:255-262. [ Links ]

13. Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis G, Burroughs A. Liver grafts from anti-hepatitis B core positive donors: A systematic review. J Hepatol 2010;52:272-279. [ Links ]

14. Lok A, McMahon BJ. AASLD practice guidelines: Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology 2009;50:1-36. [ Links ]

15. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2009;50:227-242. [ Links ]

16. Zarski JP, Marcellin P, Leroy V, et al. Characteristics of patients with chronic hepatitis B in France: predominant frequency of HBeAg-negative cases. J Hepatol 2006;45:355-360. [ Links ]

17. Perrillo RP. Acute flares in chronic hepatitis B: the natural and unnatural history of an immunologically mediated liver disease. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1009-1022. [ Links ]

18. Lalazar G, Rund D, Shouval D. Screening, prevention and treatment of viral hepatitis B reactivation in patients with haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol 2007;136:699-712. [ Links ]

19. Viganò M, Vener C, Lampertico P, et al. Risk of hepatitis B surface antigen seroreversion after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:125-131. [ Links ]

20. Yeo W, Chan PKS, Hui P, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in breast cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study. J Med Virol 2003;70:553-561. [ Links ]

21. Michel M, Duvoux C, Hezode C, et al. Fulminant hepatitis after infliximab in a patient with hepatitis B virus treated for an adult onset Still's disease. J Rheumatol 2003;30:1624-1625. [ Links ]

22. Ostuni P, Botsios C, Punzi L, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in a chronic hepatitis B surface antigen carrier with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab and low dose methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:686-687. [ Links ]

23. Esteve M, Saro C, Gonzalez-Huix F, et al. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in Crohn's disease patients: need for primary prophylaxis. Gut 2004;53:1363-1365. [ Links ]

24. Millonig G, Kern M, Ludwiczek O, et al. Subfulminant hepatitis B after infliximab in Crohn's disease: need for HBV-screening? World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:974-976. [ Links ]

25. Chung SJ, Kim JK, Park MC, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B viral infection in inactive HBsAg carriers following anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Rheumatol 2009;36:2416-2420. [ Links ]

26. Kim YJ, Bae SC, Sung YK, et al. Possible reactivation of potential hepatitis B virus occult infection by tumor necrosis factor-alpha blocker in the treatment of rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol 2010;37:346-350. [ Links ]

27. Caporali R, Bobbio-Pallavicini F, Atzeni F, et al. Safety of tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers in hepatitis B virus occult carriers (hepatitis B surface antigen negative/anti-hepatitis B core antigen positive) with rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:749-754. [ Links ]

28. Morisco F, Castiglione F, Rispo A, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and immunosuppressive therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2011;43:S40-S48. [ Links ]

29. Rahier JF, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, et al. European evidence based Consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease, J Crohns Colitis 2009;3:47-91. [ Links ]

30. Zingarelli S, Frassi M, Bazzani C, et al. Use of tumor necrosis factor- alpha-blocking agents in hepatitis B virus-positive patients: reports of 3 cases and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1188-1194. [ Links ]

31. Carroll M, Forgione M. Use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patients: a literature review and potential mechanisms of action. Clin Rheumatol 2010;29:1021-1029. [ Links ]

32. Vassilopoulos D, Apostolopoulou A, Hadziyannis E, et al. Longterm safety of anti-TNF treatment in patients with rheumatic diseases and chronic or resolved hepatitis B virus infection. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1352-1355. [ Links ]

33. Dervite I, Hober D, Morel P. Acute hepatitis B in a patient with antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen who was receiving rituximab. N Engl J Med 2001;344:68-69. [ Links ]

34. Matsue K, Kimura S, Takanashi Y, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus after rituximab-containing treatment in patients with CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma. Cancer 2010;116:4769-4776. [ Links ]

35. Tsutsumi Y, Ogasawara R, Kamihara Y, et al. Rituximab administration and reactivation of HBV. Hepat Res Treat. 2010;ID182067. doi:10.1155/2010/182067. [ Links ]

36. Iannitto E, Minardi V, Calvaruso G, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and alemtuzumab therapy. Eur J Haematol 2005;74:254-258. [ Links ]

37. Pyrpasopoulou A, Douma S, Vassiliadis T, et al Reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection following rituximab administration for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int 2011;31:403-404. [ Links ]

38. Cheng J, Li JB, Sun QL, et al Reactivation of hepatitis B virus after steroid treatment in rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol 2011;38:181-182. [ Links ]

39. Gwak GY, Koh KC, Kim HY. Fatal hepatic failure associated with hepatitis B virus reactivation in a hepatitis B surface antigen-negative patient with rheumatoid arthritis receiving low dose methotrexate. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2007;25:888-889. [ Links ]

40. Hagiyama H, Kubota T, Komano Y, et al. Fulminant hepatitis in an asymptomatic chronic carrier of hepatitis B virus mutant after withdrawal of low-dose methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2004;22:375-376. [ Links ]

41. Ito S, Nakazono K, Murasawa A, et al. Development of fulminant hepatitis B (precore variant mutant type) after the discontinuation of low-dose methotrexate therapy in a rheumatoid arthritis patient. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:339-342. [ Links ]

42. Narváez J, Rodriguez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aguilá MD, et al. Severe hepatitis linked to B virus infection after withdrawal of low dose methotrexate therapy. J Rheumatol 1998;25:2037-2038. [ Links ]

43. Loomba R, Rowley A, Wesley R, et al. Systematic review: the effect of preventive lamivudine on hepatitis B reactivation during chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:519-528. [ Links ]

44. Lau GK, Yiu HH, Fong DY, et al. Early is superior to deferred preemptive lamivudine therapy for hepatitis B patients undergoing chemotherapy. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1742-1749. [ Links ]

45. Hsu C, Hsiung CA, Su IJ, et al. A revisit of prophylactic lamivudine for chemotherapy-associated hepatitis B reactivation in non- Hodgkins lymphoma: a randomized trial. Hepatology 2008;47:844-853. [ Links ]

46. Calabrese LH, Zein NN, Vassilopoulos D. Hepatitis B virus reactivation with immunosuppressive therapy in rheumatic diseases: assessment and preventive strategies. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:983-989. [ Links ]

47. Yeo W, Johnson PJ. Diagnosis, Prevention and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation during anticancer therapy. Hepatology 2006;43:209-220. [ Links ]

48. Lau G. Hepatitis B reactivation after chemotherapy: two decades of clinical research. Hepatol Int 2008;2:152-162. [ Links ]

49. Hoofnagle JH. Reactivation of hepatitis B. Hepatology 2009;49:S156-S165. [ Links ]

50. Vassilopoulos D; Calabrese LH. Risks of immunosuppressive therapies including biologic agents in patients with rheumatic diseases and co-existing chronic viral infections. Curr Opinion Rheumatol 2007;19:619-625. [ Links ]

51. Shaw T, Bartholomeusz A, Locarnini A. HBV drug resistance: Mechanisms, detection and interpretation. J Hepatol 2006;44:593-606. [ Links ]

52. Woo G, Tomlinson G, Nishikawa Y, et al. Tenofovir and entecavir are the most effective antiviral agents for chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and Bayesian meta-analyses. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1218-1229. [ Links ]

53. Chang TT, Lai CL, Kew Yoon S, et al. Entecavir treatment for up to 5 years in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2010;51:422-430. [ Links ]

54. Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 2011;140:132-143. [ Links ]

55. Watanabe M, Shibuya A, Takada J, et al. Entecavir is an optional agent to prevent hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation: a review of 16 patients. Eur J Intern Med 2010;21:333-337. [ Links ]

56. Jiménez-Pérez M, Sáez-Gómez AB, Mongil Poce L, et al. Efficacy and safety of entecavir and/or tenofovir for prophylaxis and treatment of hepatitis B recurrence post-liver transplant. Transplant Proc 2010;42:3167-3168. [ Links ]

57. Brost S, Schnitzler P, Stremmel W, et al. Entecavir as treatment for reactivation of hepatitis B in immunosuppressed patients. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:5447-5451. [ Links ]

58. Sanchez MJ, Buti M, Homs M, et al. Successful use of entecavir for a severe case of reactivation of hepatitis B virus following polychemotherapy containing rituximab. J Hepatol 2009;51:1091-1096. [ Links ]

Correspondência: Joana Nunes; Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Hospital Santa Maria,

Lisbon, Portugal; Avenida Professor Egas Moniz 1649-035 Lisboa - Portugal; Telemóvel: +351 964 217 881;Telefone: +351 217 805 452; E-mail: joanamnunes@gmail.com.

*This article has been co-published in Acta Reumatol Port 2011;36:110-118