INTRODUCTION

According to the report from the project “Operation Zero” (2022) the Portuguese Health System as a whole is responsible for a carbon footprint of 3.92 Mt CO2eq (2014 data), which represented approximately 5.8% of total nationwide greenhouse gases emissions (GGE),1 which is higher than the world average of 4.4%.2 About one third of GGE are indirect and attributed to chemical and pharmaceutical products manufacturing. In line with the road to net zero carbon, the target is to reduce the above-mentioned carbon footprint by 69% until 2050.1

Kidney care is a focus of particular concern regarding the need for a sustainable growth, considering the increasing prevalence and incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD),3 and the high environmental impact of its therapies.4 In 2022, there were 21 198 patients with CKD stage 5D/T in Portugal - 12 878 under hemodialysis (HD), 881 under peritoneal dialysis (PD), and 7439 transplanted patients with a functioning graft. The number of prevalent patients on dialysis has increased 78% in the last two decades in Portugal.3 Dialysis carries a burden of water consumption and waste production that is disproportionally high compared to other medical therapies.5,6A few countries have manifested a high awareness of environmental issues with the development of “green nephrology” statements and programs.7-9 However, most countries are still uncertain about what means to implement and audit programs aiming towards a “greener” kidney care.

GOALS AND AIMS

A nationwide questionnaire performed to the Heads of Nephrology Departments across Portugal reported that 71% did not have access to regular and detailed data regarding consumption of resources or waste production in their department (unpublished data). When it comes to environmental management systems, it is necessary to perform an initial evaluation of the environmental status of the unit before starting off the implementation of new procedures or the introduction of improvement projects.10 The identification and quantification of the main consumptions and waste production is the first step. This requires keeping detailed records of water and energy consumption, as well as sorting and weighing waste according to its classification.

Plans to mitigate environmental impact should be stepwise and adapted to the reality of the specific center. Altering the mindset of the health community about the topic of environmental sustainability and stimulating hospital administration boards’ involvement in the goal of improving environmental indicators are also fundamental goals.

Periodic auditing is recommended in every renal unit to maintain the established goals and to evaluate the status of the environmental objectives proposed. Based on the audit, corrective measures are established with the goal of changing the procedures involved so that they become part of the daily routine.10

Finally, green nephrology programs should seek to contribute to the review of national legislation in order to safeguard the need for better management of the environmental impact of nephrology.

HOW TO IMPLEMENT?

After assuring a correct measurement of the environmental impact through keeping regular and detailed records, changes can be planned, put into practice, and audited.

There are legal requisites that need to be addressed, namely regarding waste management. The Portuguese General Health Directorate recommends that all waste generated in a HD facility should be incinerated (or equivalent, like autoclaving)11 however, about one third of this waste would be potentially recyclable. In our opinion, these recommendations are not entirely suitable to the current reality.

Units should appoint “green-persons” with communication and leadership skills who are able to provide training and report progresso to the team. A successful implementation of a green nephrology program also requires interdisciplinarity - in addition to participants from the Health sector, people from other areas of knowledge should be involved, namely Environment, Pharmacology, Engineering and Management.

Renal healthcare professionals and manufacturers should work together with the purpose of developing eco-friendly technologies, devices, and machines. Such collaboration is essential to help reduce the environmental burden and maintain good quality of treatment.

Hospital administration boards should be advised to select suppliers of sustainable materials, aiming towards a circular model involving biodegradable or recyclable materials or their repeated use (circular economy), and this may provide a return on investment in the short to medium-term.

Nephrology Visits

The main causes of ecological impact pertain to drugs’ production and distribution cycle, and patients’ transportation.

Audits should be performed annually regarding drug wasting in the hospital pharmacy, the consumption of plastic in packaging discharged to outpatient, and the economic and environmental impact related to transportation provided by the hospital.12

Ecological measures include reducing drug accumulation and waste, in collaboration with hospital/community pharmacies. Reduce drug packaging or produce it with materials that may be recycled or discarded with little environmental impact.

Other initiatives should also be considered: Implementation of a close collaboration program between nephrologists and primary health care facilities, allowing better prevention and follow-up until late stages of CKD, reducing transport to hospital visits; Development of education, training, and empowerment programs for patients with CKD in order to reduce the need for use of Health services; Optimization and expansion of telemedicine programs (with patients and with other medical specialties).12

Nephrology Ward

The functioning of a Nephrology ward generates an ecological impact that largely pertains to energy consumption and waste production resulting from the operation of the hospital. Every department should perform a monthly quantification of consumptions related to lighting, heating, food, cleaning, and laundry. Audits performed every six months should focus on the consumption of energy and water, and waste production.

Some measures to maximize energy savings are: setting computers to shut down or hibernate when not in use; prioritizing electronical records; optimizing air-conditioning use; installing motion sensor LED lights; improving buildings’ energy efficiency and installing solar panels on the roofs in places with abundant sunlight (like Portugal).

Measures to reduce water consumption and minimize waste include using biodegradable cleaning products; considering recyclable and biodegradable dishware; avoiding wasting food; printing as little as possible and choosing to shred paper (prevents it from being treated as group III (biohazardous waste); avoiding single dose distribution of drugs to minimize plastic consumption; and installing motion sensors and flow limiters on faucets.12

Central venous catheters placements and kidney biopsies are the most waste-generating procedures performed in nephrology wards. Packaging materials should be separated into its components, for example paper and plastic, in order to enable them to be recycled8.

Hemodialysis Units

HD has the greatest environmental impact of all nephrology areas, with large water and energy consumptions, waste generation, and transportation of patients. At our hospital HD unit, each treatment uses about 350 L of water and 9-10 kWh of energy. Waste generation is approximately 546 kg/patient/year, of which 37% is plastic (25% of which is polyvinyl chloride [PVC]).13 Our center does not have a central delivery system of acid concentrate, which is a fundamental measure known to reduce dialysate and plastic waste derived from dialysate bags, as well as environmental costs related to transportation.12

The European Dialysis and Transplant Nurses Association/European Renal Care Association (EDTNA/ERCA) created an environmental checklist that constitutes a method for renal care centres to evaluate their own environmental performance and offers the opportunity to seek areas for self-improvement through the implementation of environmental management programs. The questionnaire is available online (at https://www.edtnaerca.org/environmental-checklist) and consists of 40 questions. It provides an initial diagnosis, covering various areas, in order to reflect the full picture of the environmental status in the unit. The first step of commitment to improvement relies on data collection about water, electricity and energy use, and achievement of recommended key performance indicators (KPIs). Questions regarding the use of ecofriendly technologies and products for disinfection, cleaning, and waste management are also contemplated in the questionnaire. In addition, there are many non-clinical procedures to keep track of, such as air-conditioning usage, food preparation and delivery, transportation, and much more. All these activities are part of the operation of a HD unit, and therefore need to be included in the environmental status evaluation.14

The following KPIs were defined and should be measured monthly14:

- Water consumption per dialysis treatment: 350 - 400 L per HD treatment and 450-500 L per hemodiafiltration (HDF) treatment;

- Electricity consumption per HD/HDF treatment: 12 - 15 kW/h;

- Hazardous waste generation per dialysis treatment: 1.0 - 1.2 kg. The other defined KPIs should be measured annualy14:

- Sustainable use of chemical substances and disinfectants in renal care: 50% green products (without phosphates, colors, fragrances);

- Annual reduction of plastic materials in percent per dialysis center: 10% in the first year, then 5% annually until reaching the goal;

- Annual reduction of paper printouts per dialysis center: 10% in the first year, then 5% annually until reaching the goal;

- Percentage of employees coming to the dialysis center using public transportation: 25%;

- Percentage of employees coming to the dialysis center by bike or walking: 25%;

- Percentage of suppliers with certified Environmental Management System (EMS): 50%.

Water

Every HD unit should monitor the amount of water consumed per dialysis treatment, as well as the amount of water consumed by the reverse osmosis (RO) system and its recovery rate.

Modern RO systems have increased efficiency, which translates in a reduced amount of reject water, flow-adjusting ability according to the needs of the renal unit, and standby mode with minimal water and energy consumption.4,8

Reject water from RO can possibly be used for non-clinical purposes, such as window and floor cleaning, toilet flushing, car washing, dishwashing or watering a garden.4,15

Decreasing the dialysate flow rate from 500-800 mL/min to 400- 500 mL/min is not associated with a significant reduction in dialysis efficacy, especially in patients with body weight less than 70 kg. This can represent savings of up to 100 L of water per HD session.16

Energy

HD units should have an electricity meter available directly in order to evaluate if the achieved figures are within the recommended range.

Setting the dialysate to cooler temperatures, like 35.0° - 35.5°C, allows for energy saving and may improve hemodynamic stability during the dialysis treatment.17 Also, the use of heat exchangers - devices that transfer energy from dialysis effluent to the incoming dialysate - significantly reduces the energy required to heat the dialysate and have proven a favorable return on investment.18

As mentioned before, optimization of heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning, improving buildings’ energy efficiency, and prioritizing renewable energies like solar energy are fundamental measures to increase energy savings.

Waste

Waste audits assess the composition of a waste stream. They are helpful to develop and improve waste management policies and procedures, to assess appropriate segregation, to identify opportunities to increase reuse or recycling, and to monitor the impact of waste minimization schemes.19

HD units should separate waste according to its type - hazardous, sharp, plastic, paper, electrical, and municipal waste. All waste should be weighed, so that one can monitor and take measures to reduce the amount produced per dialysis treatment or per patient/year. Emptying the blood lines and dialyzer before discarding reduces the weight of hazardous waste by about 0.2 kg/session. Emptying the bicarbonate cartridge is also recommended and, in some countries, it may be considered domestic waste and therefore be recycled.11

Peritoneal Dialysis

The real carbon footprint of PD is unknown, this technique requires 6-12 L of dialysis solution daily, but there is no information available about the amount of water required to produce PD solutions nor about the carbon footprint of transporting PD solutions from the point of manufacture to the point of care. In addition, producing 1 kg of plastic requires 180 L of water.4

Plastic consumption is greater in PD than hemodialysis. However, Biofine®, a PVC-free polymer used in some packages of PD solution, is an ecological alternative to conventional plastic that requires less energy for production and does not release hydrochloric acid upon incineration. Some plastic reduction alternatives such as the U-Drain® systems have been also developed. These require installation of drainage tubing from the cycler to allow direct drainage of PD effluent into the sewage system.13

At our unit, the weight of total waste generated by each patient on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) varies between 533-613 kg yearly (35%-60% plastic waste). On automated peritoneal dialysis (APD), this grows to 671-739 kg yearly (60%-72% plastic waste) - this variation depends on the number of exchanges and on type of PD solution used.13

Telehealth and telemonitoring are increasingly important in PD patients’ care, allowing physicians and nurses to solve several health problems remotely.

PD units should also be audited on a regular basis for environmental purposes.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, conducting an environmental audit is the first step in evaluating the environmental impact of nephrology units, which unveils areas for improvement. It is extremely important to quantify and register regularly, which is the gateway towards reducing consumption and producing less waste.

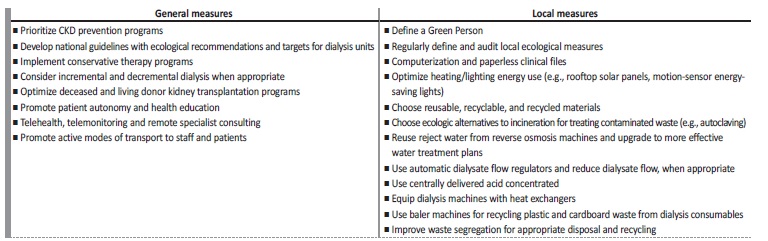

Action plans established for each unit to mitigate the environmental impact should be designed step-wise and focus initially on the aspects where the most important environmental benefits can be expected. Monitoring and measuring progress is fundamental. Units should appoint green-persons, that also have the ability of providing training to health staff and that will inform the staff about improvements achieved in environmental sustainability. Reducing the ecological impact of kidney care can be performed either locally or nationally (Table 1).

Table 1 Opportunities for implementing a sustainable kidney care

Adapted from: Francisco D, et al. Port J Nephrol Hypertens. 2021;35:6-10.13; Yeo SC, et al. Global Health. 2022;18:75.20

Finally, we must seek opportunities to refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle, and rot (the 5 R´s of sustainability and zero-waste management), as well as promote the development of a circular economy. These actions will improve the environmental, economic, and social impact and lead Nephrology towards a greener path.