INTRODUCTION

Primary membranous nephropathy (PMN) is limited to the kidney and is responsible on average for 80% of the cases of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in adults.1 In children, secondary membranous nephropathy is more common than in adults and is often secondary to autoimmune diseases and chronic viral infections.2 Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that is responsible for 20% of all secondary nephrotic syndrome cases and these patients are at an increased risk of developing end-stage renal disease (ESRD). After starting hemodialysis (HD), patients with SLE normally develop clinical and serological remission, reflected on a decrease in lupus flare frequency.3 We present the case of a patient followed for 27 years in a Nephrology consultation, that developed ESRD secondary to a seemingly PMN, developing a lupus flare after initiating HD.4

CASE REPORT

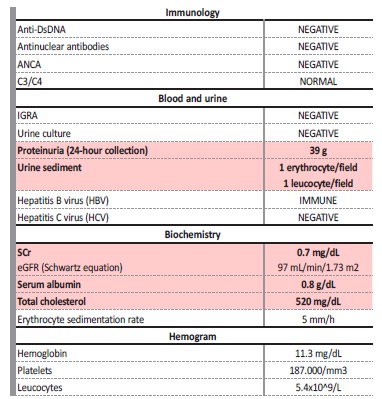

A 14-year-old male patient was referred to a Nephrology consultation in 1991 due to a nephrotic syndrome (nephrotic-range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, hypercholesterolemia and peripheral edema) with normal kidney function. The initial diagnostic workup is exposed in Table 1.

Table 1: Initial diagnostic workup.

Anti-DsDNA - anti double stranded DNA antibodies; ANCA - anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody; IGRA - interferon gamma release assay; LDH - lactate dehydrogenase, SCr - serum creatinine

A kidney biopsy (KB) was performed and, suspecting a minimal change disease (MCD), prednisolone (PDN) was initiated (60 mg/m2/day). The biopsy result was suggestive of a membranous nephropathy (MN): on optic microscopy (OM) there was increased thickness of the capillary walls and on immunofluorescence (IF) there was positive staining for IgG and C3 in a finely granular pattern. As the serologic workup was negative for a secondary cause of MN, this case was interpreted as a primary MN. Oral cyclophosphamide (CF) (2 mg/kg/day on month two, four and six) was added to the PDN regimen, with optimal clinical and analytical response. After six months, CF was stopped and the patient was put on maintenance therapy with low dose PDN for two years, during which he was on total remission (24-hour protein <300 mg/24h).

In 1993, during an episode of lower respiratory tract infection, the patient relapsed: 24-hour proteinuria increased to 5.4 g/24h. On routine analysis, kidney function was stable (SCr 0.74 mg/dL), total cholesterol and serum albumin were in the normal range and the urine sediment had no signs of activity. Clinically, the patient was normotensive and had moderate pedal edema. These findings required admission to the ward to perform another KB. This time, besides increased capillary wall thickness, there was also extracapillary proliferation; on IF, there was sub-epithelial staining for IgG (2+) and C3(+). To rule out associated systemic diseases, a new diagnostic workup was performed, once again negative for autoimmune and infectious diseases. We restarted PDN and CF, with good clinical and laboratorial response but, since the CF cumulative was approximately 9 g (140mg/kg), it was stopped after 50 days and the patient remained with low-dose PDN for three years. Across those years, proteinuria remained in the sub-nephrotic range (0.5-3 g/24h) and kidney function stabilized (SCr of 0.94 mg/dL).

In December 1996, the patient was again admitted to the ward for peripheral edema and nephrotic-range proteinuria (8 g/24h). The urinary sediment was inactive and kidney function was normal (SCr 0.97 mg/dL) as were serum albumin and total cholesterol. On OM, the KB revealed diffuse glomerular sclerosis, but no signs of active proliferative disease; on IF, there was again positive staining for IgG and C3 in a finely granular pattern. This time, he was started on cyclosporine (CYC) (5 mg/kg/day) and low dose PDN, achieving full remission (24-hour proteinuria: 346 mg) after four weeks. Combination therapy with CYC and low-dose PDN was maintained for 21 years. During followup, 24-hour proteinuria was in the sub-nephrotic range (0.8-2.3 g) and there was a progressive deterioration of renal function - an average decrease in eGFR of 4.7 mL/min/1.73 m2/year- reaching a SCr of 3.8 mg/dL in 2017. As there were no signs of primary renal disease activity, blood tests were not suggestive of a secondary disease and kidneys had a reduced size ultrasound, no further KBs were performed during this period.

On January 2018, the patient underwent urgent HD due to severe kidney function impairment (SCr 6.4 mg/dL), refractory hyperkalemia (7.2 mmol/L) and reduced urinary output in the context of a viral gastroenteritis. As kidney function did not recover during the stay at the ward, he was started on a permanent HD regimen and all immunosuppressive medication was stopped.

In March 2019, he was admitted to the Nephrology ward with chronic refractory fever (axillar temperature >38ºC) associated with an erythematous full-body rash. The patient denied respiratory distress, urinary symptoms or starting any new medication for the past months.

Blood tests showed an increased C-reactive protein (CRP) (5 mg/dL) without leukocytosis. Since his HD access was a tunneled central venous catheter, it was removed and replaced after a negative blood culture result. Large spectrum antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and gentamicin was initiated without clinical or analytical improvement. He was observed by Dermatology who suspected the diagnosis of generalized exfoliative dermatitis. The patient restarted PDN (40 mg/day for 14 days), which resolved the rash, fever and elevated CRP and was discharged with a corticoid taper over 16 weeks.

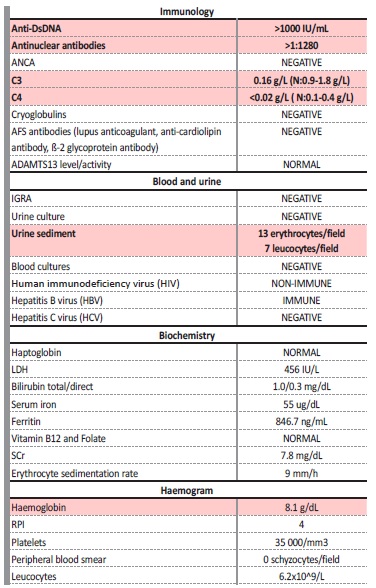

One month after PDN suspension, the symptoms slowly resurfaced and progressed, with growing severity: persistent fever, inflammatory joint pain (mostly metacarpophalangeal and elbow), involuntary weight loss (more than 5% of his body weight) and a pruriginous macular rash on his hands and forearms. He also mentioned dry cough and diarrhea that started 3 weeks before being admitted. Due to these symptoms, he had already started vancomycin, ceftazidime and levofloxacin for 2 weeks on the dialysis clinic but without any clinical improvement. A thoracic-abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan had also been performed two days before arrival, showing several adenopathies (axillar, mediastinic and para-aortic), bronchial wall thickening and colonic diverticulosis. Blood tests showed a bicytopenia (hemoglobin: 8.8 g/dL and platelets: 42.000/mm3) with increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Multiple serologies were collected (Brucella, Coxiella, Histoplasma, Schistosoma, Strongyloides and Parvovirus), as well as a full autoimmune study and serum protein electrophoresis. The patient was started on empiric antibiotic with meropenem with no clinical improvement. On the fifth day after being admitted to the ward, autoimmunity results came up (Table 2).

Table 2: Immunologic and infectious diagnostic workup.

Anti-DsDNA - anti double stranded; DNA antibodies; ANCA - anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody; IGRA - interferon gamma release assay; LDH - lactate dehydrogenase, SCr - serum creatinine; RPI - Reticulocyte Production Index

These results were compatible with the diagnosis of a SLE flare, so the patient was started on 500 mg of methylprednisolone (MTP) daily for 3 days, followed by PDN 40 mg/day (0.5 mg/kg), with clinical 5improvement but maintaining fever (38ºC constantly) and joint pain.

Two days after starting PDN, the patient exhibited sudden respiratory distress requiring high-flow supplemental oxygen associated with hemoptysis and sudden hemoglobin drop. A thoracic CT scan was performed immediately and showed an alveolar hemorrhage filling all pulmonary lobes. The patient was submitted to a bronchofibroscopy that confirmed the alveolar hemorrhage and did not identify any microorganism (neither virus nor bacteria) on bronchial aspirate. Due to the severity of the symptoms, the patient started plasma Exchange therapy on alternating days for 15 days, each exchange involving 1.5 times the total plasma volume which was replaced with albumin.

Intravenous human immunoglobulin was also started (25 g every day for 5 days). The patient’s condition improved after the second plasma exchange and he was started on mofetil mycophenolate (MMF), 1 g twice daily, on his 15th day on the ward. After a few days, anti-dsDNA antibody titers had regressed (to about 500 IU/mL) still with complemente being consumed. By the 31st day, the patient felt once again breathlessness with hemoptysis, so he was once again started on intermittent plasmapheresis which continued for 14 days with a total of 9 sessions of plasma exchange performed. This time the patient was started on CF, according to the EUROLUPUS scheme (intravenous pulses of 500 mg every 15 days) associated with MMF (1 g twice daily).

A total of three CF pulses were administered before discharge. Clinically, the patient was stable without further signs of alveolar hemorrhage. Blood tests still showed immune activity with complemente consumption (C3: 0.28 g/L, C4: 0.02 g/L and anti-ds DNA antibody about 200 IU/mL) and low platelet count (110.000/mm3). During follow-up, the patient maintained combined therapy with CF (three more IV pulses, totaling six administrations) and MMF (1 g twice daily), achieving a complete response after six months. By that time, he had no focalizing symptoms, dsDNA antibodies regressed to normal values and there was no evidence of complement consumption. Presently, the patient remains in complete remission and on a chronic HD regimen, waiting to receive a kidney transplant.

DISCUSSION

We presented a patient with a classical presentation of nephrotic syndrome followed for 27 years in a Nephrology consultation with a primary MN diagnosis. In younger patients, the most frequent causes of these histopathologic findings are secondary to systemic infections or autoimmune disorders (secondary membranous nephropathy), while in adults the primary form is more frequent. Nowadays, a diagnosis of PMN is suggested by a positive anti-phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) antibody (in 80% of the patients) or anti-thrombospondin antibody (in 10%), and classical biopsy findings. One must consider that these antibodies were recently identified and so, in the past, this diagnosis relied mostly on clinical and histopathologic findings in the absence of a secondary cause. However, many of the most common disorders presenting as a secondary membranous nephropathy, like SLE, may be masked by lack of symptoms and a negative serological test (which occurs in about 10% of SLE patients6) eventually leading to misdiagnosis; in particular, patients with class V membranous lupus nephritis, which may lack significant extra renal symptoms.

The diagnosis of SLE can be made by combining clinical and laboratory findings as outlined in the 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology (EULAR/ACR) classification criteria.7 By the new EULAR/ACR classification, to be diagnosed with SLE, the patient must have a positive ANA titer at least once during follow-up followed by a cumulative score ≥10 amongst different weighted criteria (2-10 points) grouped in clinical and immunological domains.

The seven clinical domains include constitutional, hematological, neuropsychiatric, mucocutaneous, serosal, musculoskeletal, and renal criteria. The three immunological domains include antiphospholipid antibodies, complement proteins and SLE-specific antibodies.

The incidence and prevalence of SLE and Lupus Nephritis is influenced by age, gender, ethnicity, geographical region and diagnostic criteria, but across populations, clinically important kidney disease will occur in about 50% of the patients,8 many of which will eventually develop ESRD. Normally in these patients there is evidence of clinical and serological remission upon initiating HD, thus reducing the number of flares and need for medication.5 Extra-renal manifestations of SLE can vary greatly from one patient to another: virtually all systems can be affected although the skin, polyserositis and musculoskeletal are the most common sites of disease activity. Pulmonary involvement in SLE is very common, affecting 20% of the patients, with more than 50% developing pulmonary manifestations at least once during the course of the disease, being associated with higher mortality.9,10

Because lung anomalies do not correlate with serum markers of lupus activity it is essential to rule out pulmonary infections in the initial evaluation, which occur in nearly 60% of the patients and are responsible for 30% to 50% of deaths in patients with SLE.10,11 Pulmonary involvement can be subdivided according to the main structure affected: parenchymal (Lupus pneumonitis, chronic interstitial lung disease, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage), vascular (pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary thromboembolism), pleural (pleuritis or effusion), airways and shrinking lung syndrome.

In our patient all the clues from the initial workup pointed out to a PMN: the complementary blood work did not identify any secondary causes and the biopsy results were highly compatible with the diagnosis: deposition of IgG and C3 on the glomerular basement membrane (MBG) (instead of the typical full house pattern (IgG, IgM, C1, C3) seen in SLE and other autoimmune diseases). Furthermore, this patient never developed serological or clinical SLE manifestations until reaching ESRD and HD initiation.

Although pulmonary involvement occurs frequently in SLE patients, our case is highly atypical in that this type of lung parenchyma involvement is very rare (ranging from 2%-6%), being associated with high mortality and requiring intensive immunosuppression and plasmapheresis for disease control; also, its appearance after reaching ESRD, a period typically associated, as already discussed, with reduced SLE activity, makes this case highly unusual.

One can speculate whether the initial glomerulopathy presented by the patient was an initial first manifestation of SLE or indeed a PMN in a patient that eventually developed clinical and serological SLE’s manifestations. Supporting the hypothesis of a masked SLE for 27 years is the fact that this patient was on continuous immunosuppression since the initial diagnosis, which could have kept under control SLE manifestations; also the presence of extra capillary proliferation in the second KB, unusual in primary MN, could, in retrospect, be related to a secondary cause. Although this may explain most features of the case, we think this hypothesis is less unlikely, because not only the blood work never pointed or suggested to SLE, but also the patient never developed clinical signs of SLE until reaching ESRD. Furthermore, the KB findings were never suggestive of SLE, as the most frequent histological findings were never identified. Furthermore, the KB findings, except for the above mentioned, were not suggestive of SLE, as the most frequent histopathological findings, particularly in IF, were never identified. The second hypothesis of a cluster of autoimmune diseases, represented by SLE and PMN, is, arguably, more likely. Being an autoimmune disease, SLE can be preceded or followed by other diseases from the same spectrum, with rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s syndrome being the most common associations.12 Despite there being no reported cases in literature regarding an association between PMN and SLE, the fact that PMN is a localized form of an autoimmune disorder affecting the kidney, supports the hypothesis of two separate entities, linked by a common ground of autoimmunity, playing a role in our case. All this being said, we will never know for sure.