I. Introduction

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Portuguese America presented vivid contrasts that formed it as an "extremely slow" territory simultaneously connected to an Atlantic network of people and ideas. This is a moment in history when the extraction of alluvial gold was at its peak, whether in Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso or Goiás (Brazil), attracting people from all over the world. However, these territories rapidly grew less dependent on gold, as it became increasingly scarce over the decades. In this article, we will look at these two apparently contradictory perspectives present in the daily life of these territories, based on accounts by the famous botanist Auguste de Saint-Hilaire, who left an unavoidable legacy regarding the history and geography of Brazil. It is from his reports, who was in Portuguese America between 1816 and 1822, that these contrasting notions are partly extracted from. To this end, specific excerpts from his work will be discussed, mainly regarding moments in which the Frenchman was in the provinces of Minas Gerais and Goiás. As documentary evidence, some correspondence from the Portuguese administration of the time will also be considered, especially those that alluded to, in one way or another, the characteristics of "extreme slowness" and an Atlantic network of people and ideas. Nonetheless, we have no intention of exhausting the debate. The scope of this article is to highlight this territorial contrast present in the discourses of the time, examining the inconsistencies and complementarities of this debate. We begin with the notion of “extreme slowness”.

II. Extreme slowness

In the opening pages of the third volume of his article, Voyages dans l'intérieur du Brésil, Auguste de Saint-Hilaire provides the reasons why his work would still be up to date, even though it was published 31 years after his arrival in Brazil:

In remote lands, things change only with extreme slowness; the elements of great improvements are lacking; a rare population scattered over an immense surface, more or less left to its own devices, enervated by a scorching climate, without emulation, almost without needs, changes nothing, wants to change nothing and knows how to change nothing. (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, p. vii)

At this time, the characteristic of inland Brazil would be the “extreme slowness”, leading to the features that would keep his work up to date at the time of its release. With regard to rhythm as an analogy in the stereotyped description of people and cultures, Laurent Vidal, in his work Les hommes lents : résister à la modernité (XV e - XX e siècle), demonstrates its use in the construction of the idea of modernity and, therefore, in the constitution of a new social rhythm. As the author states:

the invention of the "economic man of modernity" is part of a new cultural relationship with work, valorizing promptness in its execution. While the weakest and most fragile have difficulty gaining access to this model of civilization, the persistence of words and images in discriminating against their way of life and pace of life enables us to point the finger at them, the better to cast them to the margins. (Vidal, 2020, p. 47)

It was precisely on the margins that we find Goiás, Mato Grosso and certain parts of Minas Gerais in the descriptions of Portuguese America, a few decades after its auriferous pinnacle. This attribution of slowness and laziness also led to a conception of lack of productivity and a large territorial void. An example of this can be found in two moments when Saint-Hilaire was dissuaded from continuing his travels to Goiás when he was still in Minas Gerais.

The first was in São João d'El Rei, where he met the town's parish priest who:

(…) did everything he could to get me out of undertaking the journey of this province. I wouldn't encounter, he told me, but fields of fatiguing monotony, where the sun is burning, where provisions are often lacking, where there is a risk of becoming dangerously ill. (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, p. 96)

The same ecclesiastic "had visited the church of a village of Indians, and everything he told me about this race proved that it was foreign to the idea of future, as I had observed myself" (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, p. 96). The mention of indigenous people is no coincidence. They, along with the enslaved, were often seen as inconsequential, impetuous and lazy. Vidal addresses this association with "slowness". Referring to texts from the first two centuries of the arrival of Europeans in the Americas, he says: "The round of words continues to impose the imagery of the lazy Indian", often portrayed in iconography alongside hammocks (Vidal, 2020, pp. 51-52).

The second temptation for Saint-Hilaire not to continue his journey to Goiás was when he crossed the Paranaíba River, the current border between the states of Goiás and Minas Gerais. The traveler states:

the heat was excessive (...). No houses, no trace of cultivation, no cattle in the pastures, no travelers on the roads, almost no flowers, no notable change in the vegetation (...). I was desolated to make such a tiring journey for so little, and almost tempted not to go as far as Villa Boa. (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, p. 267)

We can see that the heat, the emptiness, the boredom, the monotony and even the lack of interest as a botanist held Saint-Hilaire back on his journey. Curiously, when describing the Paranaíba River itself, he states that "There, it can have the width of our streams of third or fourth order; its course is very slow; a thicket of trees borders it on both sides, and a few cottages are spaced on its right bank" (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, p. 267). Once again the association of slowness with a natural environment with little or no human presence, nor of its main economic activities. However, the Frenchman surpassed his initial impressions of Goiás, since, on his journey to the south of the province, months later, he offers us distinct impressions:

This period of my journey was certainly one of the happiest. Since the Pilões river, I hadn't had the slightest reproach to make to my companions; I was enjoying perfect health and was becoming more and more accustomed to the daily fatigue and privations. I was almost angry to think that this kind of life would soon come to an end. The peace and freedom I enjoy in these wastelands," I said to myself, "will surely one day be the object of my regrets; if I see men, it's only for a few moments, they only show me their beautiful side... (Saint-Hilaire, 1848, p. 207)

This declaration of love for the solitude, the pays désert, the peace and freedom experienced in Goiás is the product of a traveler immersed in a slow life, devoid of excess, but abundant. Shortly afterwards, on Saint Louis' eve, Saint-Hilaire declares that:

I want to celebrate with my people in the middle of the wilderness. The life I was living in Brazil, despite the fatigue and privations (...), was pleasing me every day (...) I did not think anything of my return to France. (Saint-Hilaire, 1848, p. 220)

We are faced with alterity of the "European self and the Luso-Brazilian other", as put by Amilcar Torrão Filho (2008, p. 8) and largely debated since Charles La Condamine's Relation abrégée d’un voyage fait dans l’intérieur de l’Amérique méridionale (1745) and before. The presence of this "other", quite recurrent in so-called "scientific voyages", is what Daniele Laplace-Treture defines as the "other-inhabitant", in contrast to the "other-reader" who is equally present in the construction of these travel narratives. The question of alterity and the geographical element of the debate are to be found in the articulation between the object, the inhabitant, and the reader (Laplace-Treyture, 1998, pp. 77-80). Hal Langfur also considers the "contradictory image of Luso-Brazilian lassitude and greed-driven magical thinking" associated with the "authoritative explorers" that arrived in Brazil in the early 19th century (Langfur, 2023, p. 285), constituting what Mary Louise Pratt`s defined as "anti-conquest", a term that refers "to the strategies of representation whereby European bourgeois subjects seek to secure their innocence in the same moment as they assert European hegemony" (Pratt, 2003, p. 7). As for this "Enlightenment science" to which Saint-Hilaire certainly belonged to, Neil Safier (2008, p.9) states that it was "not an omniscient, universal knowledge of the natural world but rather a partial and contingent knowledge". The collective imagination produced by these scientific voyages also led to the construction of other comprehensions that were to be reproduced over the next centuries.

The correlation between slowness and unproductivity is largely supported by the sense of corruption. An example of this is a letter written in 1760 by the governor of Goiás, João Manuel de Melo, to Paulo Carvalho e Mendonça, brother of the Count of Oeiras and future General Inquisitor and Cardinal of Portugal, in which he gives his initial impressions of those lands: "this captaincy, in addition to having been poorly created, has been so badly abused in recent years that it is totally perverted"(Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, 1760). This perception of abuse of resources persisted after the governor's death. In 1771, the king of Portugal, José I, issued instructions to the next governor of Goiás, José de Almeida Vasconcelos, reporting on the state of the captaincy:

one might have expected that the Captaincy of Goyaz would be one of the most important colonies in the whole of Portuguese America, but on the contrary, what is stated in the same account is that the said Captaincy was poor, and for the most part uncultivated and uninhabited. (...) It would take large amounts to substantiate all the extortion, disorder, embezzlement and violence practiced in that unfortunate captaincy by those who had been entrusted with the government of the people and the administration of justice and the treasury. (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, 1771 [1777])

Fernando Lemes connects this administrative issue to the distance between Goiás and Portugal, stimulating the political participation of the local elites and, at the same time, relieving the governors "of certain impositions and obligations". The author also mentions the "precariousness of the means of transportation" and the "size and diversity of Portuguese America" as important factors when discussing the Luso-Brazilian administration in Goiás (Lemes, 2005, pp. 86-87). The distance between Vila Boa and Lisbon would be "an almost insurmountable barrier" that served "as an obstacle to the complete and immediate execution of the king of Portugal's determinations" (Lemes, 2012, p. 113). As such, distance can also be seen as an argument to justify the captaincy's inadequacy to the royal orders (Maluly, 2022), even though the "extreme slowness" was not in line with the standards set in the need to maintain a constantly active, dynamic and commercially interesting territory to the colonial administration. Nevertheless, Mary Karasch (Karasch, 2002, p. 143) is emphatic in stating that Vila Boa, the capital of Goiás, "played the role of a regional core subject to the Overseas Council and Lisbon rather than to the viceroys resident in Salvador da Bahia or Rio de Janeiro”. This Atlantic relation would not depend on physical issues and would attend much more to the political requirements of the royal court. Would this not be in contradiction with the extreme slowness portrayed by Saint-Hilaire?

III. The smuggler of rodez

On May 9, 1819, at the military post of Santa Isabel, located on one of the routes connecting the province of Minas Gerais to Goiás, Saint-Hilaire provides an anecdote that evokes the Atlantic connections present in the daily life of the "extremely slow" territories.

He begins by recalling the heat he had experienced over the past three days: "the thunder could be heard, water was falling every day, and yet the heat was unbearable" (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, p. 275). Passing through the small streams that fed the São Francisco river, one of which is the Santa Isabel (which is said to be marshy on its banks, as it is an intermittent river, meaning it can even cease to exist superficially in times of drought), the Botanist arrived at one of the military posts of the Villa Rica cavalry regiment (present-day Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais). There were only two soldiers, part of a nine-man detachment from Paracatú, who were in charge of checking all those coming from Goiás so that they wouldn't enter the Captaincy of Minas Gerais with diamonds or powdered gold. He also points out that they were not allowed to pass with "Spanish piastres, without a wedge bearing the arms of Portugal" (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, p. 276). Furthermore, it was at the Santa Isabel post that taxes were collected on all goods brought from Goiás to be sold in Minas. At this point, we can exemplify his comments on the Portuguese administration in Brazil and how his interests were not specific to botany:

I do not need to point out how absurd it is to demand duties on the production of one province when they pass into another; how absurd, above all, it is to put taxes on the exit of a land such as Goyaz, which, in its remoteness alone, already finds so many obstacles to the export of its products. (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, pp. 276-277)

Distance appears once again as a fundamental element of the territorial debate. It is at this point in the story that he announces: "It was in Santa Isabel that I learned the end of the adventures of a French smuggler who had inspired some interest in me by the strength of his will and his perseverance". Saint-Hilaire then clarifies that he did not write anything about it in his notebooks, "so as not to run the risk of compromising the man", making his account from what he could remember (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, pp. 276-277).

Earlier, on his way back from the Diamond District, in Villa do Príncipe - Minas Gerais, he had heard of the presence of one of his compatriots in town, and immediately desired to meet him. This unknown man was in his thirties, "slim and very tall", and they soon started talking. He was originally from Rodez, "where he worked as a butcher, when the destruction of the imperial government led him into bad business" (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, p. 277). After reading about the Englishman Mawe's travels in Brazil (a work also frequently cited by Saint-Hilaire), the former butcher began to dream of the fortune he could make with the gold and diamonds of Brazil, and soon set off for Marseille and, from there, Lisbon. After begging the French consul in Lisbon to give him a chance to go to Brazil, the individual from Rodez manages to board a warship to land in Brazil. After serving the ship's captain, who promised him nothing more than transatlantic passage, upon his arrival in Rio de Janeiro, the captain managed to obtain a passport so that the former butcher could leave for Villa Rica. It is worth recalling that until 1808, the entry of foreigners into Brazil was forbidden, as was trade with nations other than Portugal. However, even in imperial times, entry into Minas Gerais, at least for foreigners, still required authorization from local officials. Saint-Hilaire underlines this repeatedly throughout his itinerary, often needing recommendations to be welcome in the cities. Entry into the Diamond District was even more forbidden: "Subjected to a particular administration, closed not only to foreigners but also to nationals, the Diamond District forms a sort of separate state in the middle of the vast empire of Brazil" (Saint-Hilaire, 1833, p. 2). In Villa Rica, the man from Rodez joined forces with an English smuggler, "then left him and went to the Serro do Frio", the diamond-mining region of Minas Gerais. "There, he learns all the mysteries of diamond smuggling, gets to know the black men who steal these precious stones, and penetrates the district whose entrance was so strictly forbidden". Finally, Saint-Hilaire tries to dissuade him from continuing his illicit practices. However, "diamonds could make him rich; he was determined to run any risk to achieve the goal he had pursued until then, and my representations were useless". After promising to keep a letter from the smuggler to send to his family, he never reappeared. Saint-Hilaire learned at the Santa Isabel military post that he had been arrested and prosecuted for smuggling. He continues: "The corporal added to his story that this man had retired to the outskirts of Sabará, and I do not know what will become of him.". Concluding the anecdote, the Botanist says: "It is regrettable that such singular perseverance did not have a nobler purpose" (Saint-Hilaire, 1847, p. 279).

This tale allows us to glimpse the scale of the individual and his or her body in the vast Atlantic network, often referred to in the grandeur of empires and continental maps, while overlooking the people who constituted the material circulation of this network. Jesús Bohorquez points out the importance of pursuing:

a global history which, while accounting for the world of existing connections, does not simply pay attention to them, but also refers to a deep local history. Once again, it is a matter of observing how local interstices connect to, or are structured and restructured by, various chains of direct and indirect interactions and causalities that are neither simply limited to nor opposed to the local. (Bohorquez, 2018, p. 91-92)

This translocal global history, for us also associated with a historical geography of territories that relates to "the construction of the local in a global key", must, according to the author, respond to the challenges of the "big questions". These questions rely, necessarily, on our concept of what composed this Atlantic network. In which measure is the individual and his or her body a key aspect in analyzing the construction of relations overseas?

IV. Atlantic network of people and ideas

When evoking the Atlantic, we direct our thoughts to empires, world trade, cartographers and itineraries that sought to apprehend the known world as "precisely" as possible. Scientificity, ennobled by the Enlightenment and elevated to new heights with the "planetary consciousness" suggested by Carl von Linné's binomial nomenclature of all beings in the world (Maluly, 2020; Pratt, 2003), led the 18th century to observe the territory on a global scale. Pedro Cardim et al. (2014) offer a concept of what would be "polycentric monarchies", the direct product of Atlantic interactions, in which "clearly defined domineering centers" such as Madrid and Lisbon would not simply exercise absolute influence over subordinate territories. We would shift away from the notion of "composite monarchies" towards a deeper understanding of the social, political and economic relationships that shaped these territories (Cardim et al., 2014). Fabrício Prado (2015, p. 7) adds to this logic the importance of considering the active participation of "colonial agents", not only "in the pursuit of their own agendas", but also shaping "imperial administration, trade, and politics". For Tomar Herzog (2015), the Atlantic was composed of a "territorial contiguity" established between the Iberic kingdoms and their colonies. Luís Filipe Thomaz (1994, p. 208) in turn associates the constitution of these empires with forms of interconnected networks, asserting, "Most empires based their political unity on an economic and cultural unity-which presupposes the circulation of goods, people and ideas, thus a system of communications, a network structure". Given that the Atlantic can be understood as a network of relationships, contiguous in certain ways, discontinuous in others, how can we bring individuals and their ideas into this debate? Milton Santos distinguishes between "hegemonic times" and "non-hegemonic times", each formed by its own actors. The constant dialectical and simultaneous conflict between these different "temporalities" and the different uses of space and time would be what would form "such diverse daily lives" (Santos, 1994) in which individuals and their ideas would be inserted- materialized, in our understanding, in their bodies and in their actions.

Delving deeper in this discussion, Muniz Sodré (2002) conceptualizes the "body-territory" as the individual's perception of "the world and its things from oneself". The author proceeds: "The body serves as our compass, our means of orientation in relation to others". For Eduardo Miranda (2014, p. 69), the "body-territory" refers to "the individual who understands what surrounds him from his own body". In other words, forms of apprehension and formation of the territory and its various territorialities, understood by Marcel Roncayolo (1997, p. 184) as a form of "identity, which cannot be limited to that of the individual". Finally, Rogério Haesbaert (2007, p. 25), for his part, treats territoriality as "an immaterial dimension, (...) as "an image or symbol of a territory, it exists and can effectively be inserted as a politico-cultural strategy". For the purposes of this article, it is of the utmost importance to associate the different scales that positioned the "extremely slow" territories in the "Atlantic network of people and ideas", ranging from the grand intentions of empires to the individual who, with his or her body, made the decisions that formed, along with a myriad of other individuals, the territory in their reality, in their daily lives.

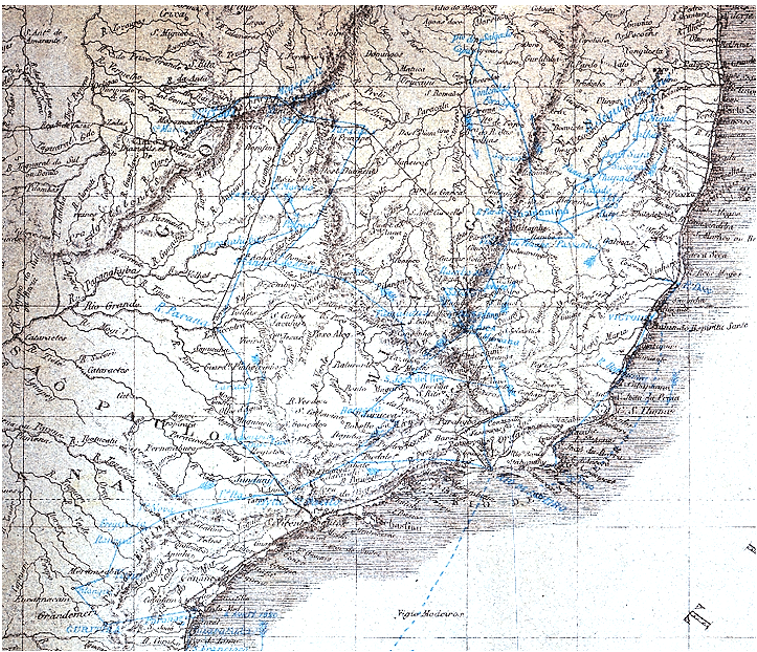

In terms of territoriality and the importance of the body-territory, when dealing with the "extreme slowness" and the Atlantic network of people and ideas, figure 1 can subjectively add to the discussion. It was attached to the posthumous version of Auguste de Saint-Hilaire's work, Voyage à Rio-Grande do Sul (1887) and is a first attempt to map the itinerary travelled by the French naturalist. It is not the purpose of this article to carry out a technical analysis, but the very existence of the map in this case provides us with elements that help us understand what has been discussed so far. By visualizing the paths taken by the Frenchman, we can see the territorial limits imposed on Enlightenment science. Although there were many sacrifices and mishaps faced by the botanist, we should note that he did not extensively penetrate the territory of Portuguese America. Keeping to the routes closest to the coast and the most populated centers, such as the "arraiais" (mining centers) of Minas Gerais, Saint-Hilaire managed to obtain only limited knowledge of the more remote regions of the colony, relying on secondary information. As put by Cláudia Damasceno, he was one of the first foreigners to explore and describe the auriferous regions of Brazil (Damasceno, 2016, p. 228). Many regions were off-limits and others were of little use to his research. Therefore, when we discuss such a landmark contribution to the history of Portuguese America, especially in the global construction of the imaginary of Brazil throughout the 19th century, it is essential to recognize the material limits imposed upon these itineraries.

Fig. 1 Itinerary of the five journeys made in the interior of Brazil, 1816-1822, by Auguste de Saint-Hilaire.

Although we are referring to a Portuguese America connected to an Atlantic network, we must also emphasize which Portuguese America we are discussing. As García-Redondo and Moreno-Martín put it (2021, p. 1), we are moving away from the idea of a "New World (...) as the static stage where the investigations and experiments undertaken by Europeans (or at the service of Europeans) took place", highlighting "local knowledge beyond its locale of production and its dissemination and universalisation as a multi-layered and multi-directional process of exchange, negotiation and integration of agents and knowledge". The importance of the colonial "sertão" (backlands) emerges, seen by Leonardo Barleta (2021, pp. 240-241) as a catalyst for an "ebb and flow of people, information, and goods", where "even though people move beyond political boundaries, they do so in particular ways according to changing spatial conceptions, social norms and practices, institutional framework, and physical conditions". The reinterpretation of the past through local agents and territorial impositions highlights what we refer to as the territorial contrasts of Portuguese America.

V. Territorial contrasts in portuguese america

When Saint-Hilaire details the route of the smuggler from Rodez, he brings up an essential detail for understanding the territorial contrasts in Portuguese America. When the mystery man was in Serro do Frio, in the Diamond District, he "gets to know the black men who steal these precious stones". This passage can be read en passant, associating it with the colonizing account constructed by the French botanist as a "seeing-man" (Pratt, 2003, p. 7). It would be the product of a vision imbued in alterity towards the population that inhabited the interior of Portuguese America. In fact, it is important to highlight the way in which characters who are often highly regarded by an entire country, such as Saint-Hilaire in Brazil, reproduced racist and reductionist discourses, especially when it came to blacks and indigenous people. However, it is also relevant to associate this perspective with the daily experience of the territory, especially from the point of view of those who lived there at that time.

In 1755, Ângelo dos Santos Cardoso, Secretary of the Government of Goiás, wrote a letter to Diogo de Mendonça Corte Real, Secretary of State for the Navy and Overseas Territories in Portugal, reporting on the general state of that captaincy (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, 1755). At one point in the document, the means of traveling in Goiás are compared with those in Portugal. In the kingdom, it was assured that those who wished to travel to the limits of the territory would have the right to "sleep under tiles and with set tables". In Brazil, it was the opposite. Travelers slept under trees, exposed to nature, with a hammock as their best equipment, at the risk of being "attacked by tigers, hideous snakes" and, worst of all, "by their own slaves" while they slept, not to mention the natives who attacked them on the roads. This description, aggressive in its own words, placing the native and enslaved peoples in the position of threats to the colonizer, associates a fundamental element with the material and moral situation of Goiás: violence.

Carla Anastasia (2005, p. 23)offers a detailed description of the violent image attributed to the mines in general. She underlines the guilt of the atrocities normally associated with the so-called "black" inhabitants (even if there was a big social distinction, for example, between those who served the enslavers and the enslaved themselves), located or not in quilombos. They were considered "enemies" of the "whites" and, as one penetrated the territory, the greater the fear of being attacked by them (again according to the colonizer's vision, as reported in the letter above). The author establishes an understanding of remote territories marked by violence as "lawless zones", i.e., "spaces, par excellence, for the exacerbation of violence". The further away from the coast, the more violent the imagery of a given territory. This understanding also brings to light the importance of the more distant territories, forming the aforementioned "sertão". The imaginary created about them is the foundation of Langfur's statement that "the 'soul' of Portuguese America lay not along the coast in the eighteenth century but inland" (Langfur, 2006, p. 4). It is precisely from this perception of the soul that the imagery of colonization is built, forged from different and overlapping times and experiences, according to Santos.

Based on the accounts presented above, we can glimpse the different actors who contributed to the simultaneous perception of an "extremely slow" territory, connected to an Atlantic network of people and ideas. It is precisely in this contrast that the perception and imaginary construction of territory takes place. In the cases previously presented, we have the colonizer, the smuggler (not identified precisely so as "to not compromise him") and the "blacks" responsible for teaching him how to commit his crimes. The different times of these different actors is the true nature of this territory, seen from above, by maps, and from below, by bodies. The territory of the map and the territory of the body do not contradict each other, but necessarily contrast, and it is in this dialectic context that geographical space is formed. In this case, a complex equation that cannot help but also contain corruption, distance (physical and argumentative) and violence. In this extremely dynamic and trans-scalar context, let us consider the contributions of João Fragoso, Maria Gouvêa and Maria Fernanda Bicalho with regard to the promises brought by the "New World":

There was nothing more dreamt of by the "conquerors” - most of whom were men from the lower nobility or even the "rabble" - than the possibility of expanding their material, social, political and symbolic wealth. Once again, the New World - as well as several other territories and overseas domains of Portugal - represented for these men the possibility of changing their "quality", of joining the nobility of the land and, consequently, of "bossing" other men - and women. (Fragoso et al., 2001, p. 24)

Weren't the promises of the new world and what was “found” overseas responsible for the conception of the "extremely slow" territories, but which nevertheless received people and ideas from the most varied origins and with the most varied intentions? In our understanding, the key is to never neglect the diverse times of people and territories that made up the fabric of Portuguese America's geography and history. It is in the simultaneity of these times that scales interconnect, coexisting and emphasizing the territorial contrasts.

VI. The geography of it all

Based on the above, it seems pertinent to highlight what can be added to the debate from a geographical point of view. The Atlantic has been widely discussed in historiography and is still a focal point for different perspectives aimed at rethinking the colonizing logics and the way in which this past is discussed. Recently, the "Atlantic world" considered "as an open system" has been put to debate, as emphasized by Ricardo Padrón (2020, p. 23) when discussing its connections "to the rest of the world by way of the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific". In our contribution, we aimed to bring some concepts that can add new insights to this debate. We presented a critical reading of Portuguese America's territory, fundamentally formed by contrasts, especially when dealing with the broad relations of the sea and the "extreme slowness" of everyday life. In which other means can geography contribute to this discussion? Would we be in terms with Gaetano Ferro's (1989) "historical geography of the sea"?

According to Paulo César da Costa Gomes (2017, p. 143-146), geography, more than a science, is a way of thinking. What he calls "geographical frameworks" would be "a way of organizing thought that prioritizes drawing, tracing, when we consider the location of things, people and phenomena". In this sense, although we have provided only one map, it is precisely in the organization of specific optics that the geographical dimension is conferred. Thus, thought is spatialized. This becomes apparent as soon as scales become the focus of our analysis, connecting all the other perspectives presented. The multiplicity and overlapping of different times, as defined by Santos, seems to us to be a way of thinking, in a scalar way, about the simultaneous occurrence of phenomena that contribute to a larger construction. In this case, to consider territorial contrasts that can not only oppose each other but are intrinsic and necessary to one another. In the dialectic of contrasts, we enter the merit of reflecting on the agents of the territory in their different positions and which are not confined to their positions. In other words, the example of the smuggler from Rodez, who is an individual who contributes, at the same time, to the Atlantic reading of connections of people and ideas and, equally, to the materialization of corruption, distance and violence, often attributed to "extremely slow" territories. In fact, the end of his journey in Portuguese America is precisely in the "sertão", theoretically opposed to the global dynamism of the Atlantic. When Auguste de Saint-Hilaire brings us the anecdote, the colonization process materializes in his discourse, from the individual will to pursue wealth in the "new world" to the collective imaginary of the "blacks" who are held responsible for his crimes. The reasoning behind the reconstruction of past narratives is not intended to be linear and, therefore, geography actively contributes to this. This is what Robin Butlin describes as "the imaginative reconstruction of phenomena and processes central to our geographical understanding of the dynamism of human activities within a broadly conceived spatial context" (Butlin, 1993, p. 1).