I. Introduction

“If it works, it’s fabulous! However, we have to be prepared for maybe some things won’t work and, if they don’t work, how we rectify them to make it work”, remarked one business owner from Wellingborough when asked to reflect on how policies adapt to different places. “I think when it’s a failed [policy], it’s a very difficult situation and people are suspicious sometimes about why you want to speak with them”, commented a senior director from Blackpool on the differential aspects of studying sites of policy absence. While voiced by stakeholders with distinct roles in urban politics, both statements speak to the broad aim of this article to understand the differential methodological issues and implications of researching sites of policy presence and absence. This article builds on a small but steadily ballooning body of geographical literature that has devoted its attention to study the inter-urban circulation of policy ideas. This strand of work, termed urban policy mobilities studies, has centered on understanding the processes and practices through which policy knowledge is made mobile from one jurisdiction and ultimately translated into another (Baker & Temenos, 2015; Jacobs, 2012; Temenos & McCann, 2013). While urban policy mobility research has consistently theorized contemporary policymaking as both relational and territorial, its empirical studies have largely focused on policies that have been successfully emulated and implemented elsewhere (McCann & Ward, 2015). There is, however, a subtle-yet-growing feeling among local policymakers and academics that sites of absence can also shape policy futures (Lovell, 2017; Temenos & Lauermann, 2020). This article provides a collection of reflexive learning practices that assimilate the methodological issues and implications wrapping the comparative study of sites of policy presence and absence. In doing so, it argues that researching such dissimilar policy arenas should encapsulate mutable and flexible research designs and strategies to better attune to the processes and politics surrounding those policy outcomes. In particular, we advocate that urban policy mobility scholars must be sensitive to - and ultimately are influenced by - issues of positionality, institutional memory and chronopolitics as they regulate our angle of arrival to the research field.

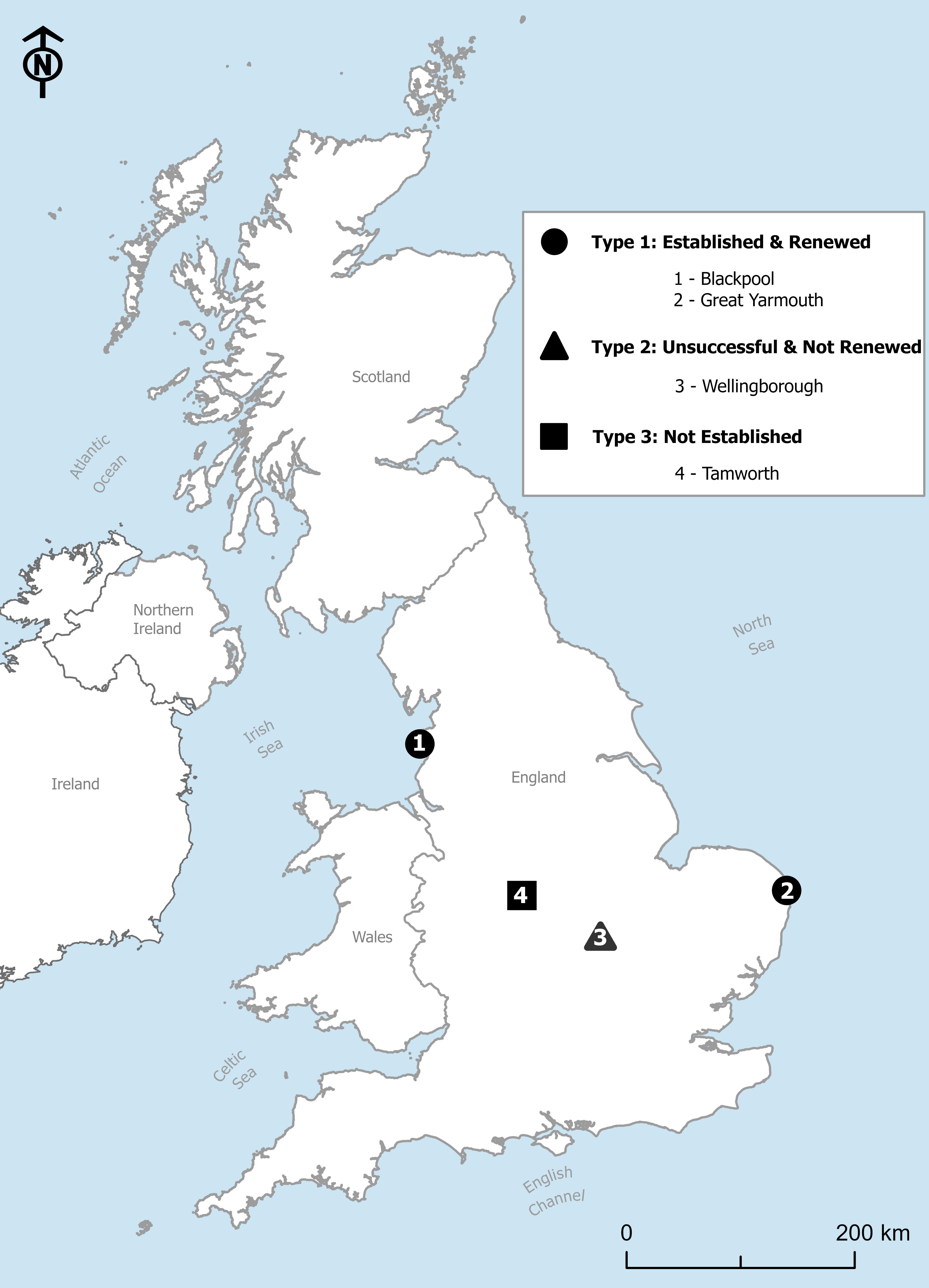

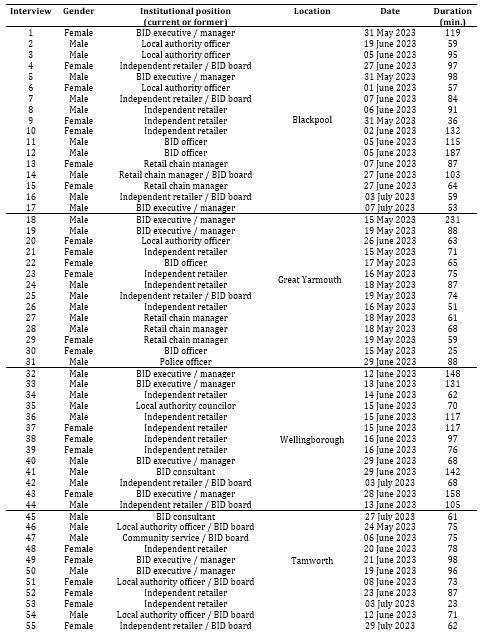

This article builds upon a multi-sited comparative academic project conducted in four English town centers. It puts specific sites of policy presence (Blackpool and Great Yarmouth) and absence (Wellingborough and Tamworth) into relational conversation as a means to expand our understanding of contemporary policymaking processes. It does so by drawing attention to Business Improvement Districts (BIDs)’s adoption as an illustrative example of how contemporary economic development policies can be empirically constituted through relational instances of presence and absence. BIDs are local public-private partnerships that act in a geographically bounded area in which businesses democratically vote to pay a levy that is ring-fenced for financing some placemaking services over a typical five-year term (Silva & Cachinho, 2021). While the process of forming and developing a BID begins with a local ‘demand side’ followed by a feasibility study, whether a BID becomes legally binding depends on the support engendered among potential levy-payers in a democratic ballot (Cotterill et al., 2019). In England, for a BID to form it is required that at least 50% of levy-payers by both the number and ratable value of votable businesses must vote for its establishment (policy presence). If either of these criteria are not met, then the BID will not be formed (policy absence). Near the end of its term, a BID may seek to renew its operations through another ballot or decide to end its existence. Although this may seem a fairly straightforward procedure, it masks that urban policymaking is far from being a neutral process, in the sense that forming a BID remains a power-laden affair, usually vested with local, multi-sectorial and overlapping interests and choices. Moreover, there has been little effort to problematize and reflect on the methodological issues of researching sites of policy presence and absence within urban policy mobility scholarship. Drawing on our research experience in four town centers where BIDs were subject to both successful and unsuccessful ballots, this article stands as an invitation to critically reflect on how positionality, institutional memory and chronopolitics mediate our access to, and navigation through, sites of policy presence and absence.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The next section introduces some of the theoretical orientations of urban policy mobilities studies and an overview of their methodological practices. Next, the article provides a reflexive reading of our research strategies and advances some methodological tactics on how urban policy mobility academics can approach sites of policy presence and absence. In concluding this discussion, the article expands the ideas of positionality, institutional memory and chronopolitics to emphasize their fundamental relevance in studying instances of policy presence and absence.

II. Researching urban policy mobilities: taking stock and new reflections

Thinking ‘the urban’ through comparative practice is not a recent intellectual enterprise. For instance, earlier inter-urban comparisons date back to European colonialism (King, 1977). Over the last few decades, there has been, however, a steady revival of thinking comparatively in a range of disciplines. Urban geographers have since early comfortably found their place within such debates (Baker & Temenos, 2015; McCann & Ward, 2013; Peck, 2011; Temenos & McCann, 2013). Their attention has been translated into several works, termed ‘urban policy mobilities studies’ (Jacobs, 2012, p. 418), which have focused on examining how urban policies are “made mobile (…) and the processes through which policies are re-made as they move across space” (Cook et al., 2014, p. 807). Embedded in this set of works is a renewed interest in exploring how policymakers and their cities draw comparative imaginaries with, and in reference to, elsewhere as a learning tactic to reinvent policy futures (McFarlane, 2011; Robinson, 2015; Ward, 2010).

While the foundations of urban policy mobility studies have been discussed in earlier contributions (McCann & Ward, 2013; Peck, 2011; Temenos & McCann, 2013), four of them are worth briefly outlining here. The first of them draws on a relational-territorial approach to critically examine urban policymaking as a process that is mutually mediated by inter-urban comparison practices and by situated political, institutional, economic and social contexts in which policies arrive (McCann & Ward, 2013). Second, there has been a sensitivity to follow the variety of practices and places through which policies are learned and put to work elsewhere by a range of social actors (Baker & McGuirk, 2019; Craggs & Mahony, 2014; González, 2010; Montero, 2016). Third, there has been a prevalence of studies focused on following policies that are ‘present’ and that have been rendered mobile. Examples range from urban regeneration (González, 2010), sustainability (Montero, 2016; Wood, 2015a) to economic development policies, as the likes of BIDs (Didier et al., 2012; Michel & Stein, 2015; Ward & Cook, 2017). However, as McCann and Ward (2015) have argued, it is important to redirect intellectual attention toward sites of absence and immobility as empirical instances of differentiation and as a way to expand our understanding of ‘the urban’. Fourth, and finally, urban policy mobility studies have focused on examining the spatialities over the multiple, often non-linear, temporalities of policy circulation. Noting the risks of methodological and analytic presentism accompanying copious urban policy mobility studies, scholars have acknowledged that policymaking processes are often made of repeated ‘starts’ and ‘stops’. Researching them thus require the use of historical and retrospective approaches to trace policy adoption across space and time (Baker & McCann, 2020; Ward, 2018; Wood, 2015a, 2015b).

Together these and other aspects open a set of methodological challenges. In broad terms, urban policy mobility scholars have attempted to ‘follow the policy’ and ‘study through’ the sites and situations of policymaking. In doing so, they have aimed to trace the multiple, often multi-sited, practices and social actors involved in the relational making of policies and capture the local context in which they are re-embedded (Cochrane & Ward, 2012; McCann & Ward, 2012; Peck & Theodore, 2012). To address these issues, and echoing the early work of Prince (2010, p. 173) who argued that “an implemented policy is an assemblage of texts, actors, agencies, institutions and networks”, urban policy mobility studies have relied on assemblage thinking as a suitable methodological-analytical framework (Baker & McGuirk, 2017; Wood, 2015b). Since then, there has been quite a lot of attention to understanding policy circulation and adoption as processes made of multiple and overlapping interactions driven by human/institutional exchange of verbal, visual and symbolic knowledge (Wood, 2015a), produced and shared through sites of learning and exchange, such as conferences and study tours (Baker & McGuirk, 2019; Craggs & Mahony, 2014; González, 2010; Montero, 2016), and ultimately made available through a web of materialities, including policy documents, presentations, consultancy reports and how-to guides (Freeman, 2012). Put simply, the methodological repertoire on which urban policy mobility studies draw has centered on observing and interviewing individuals in powerful positions (policymakers, consultants and business elites) involved in the making of urban policies (following the people), on accessing and critically examining the content and discourse of a range of policy documents (following the materials) and on observing the staged atmospheres of the situations in which policies are articulated and showcased (following the meetings).

While much has been written about the ways through which urban policy mobility scholars study how urban policies are drawn from one place and introduced in another, there are a number of practical considerations that remain to be discussed. Building upon the former theoretical and methodological foundations and literature on researching elites (Harvey, 2011; Mikecz, 2012; Natow, 2020; Smith, 2006; Thomas, 1995; Ward & Jones, 1999; Woods, 1998), this article advocates that urban policy mobility scholars should explicitly consider nuanced and mutable research approaches in how they gain access to, and navigate through, their research field when studying sites of policy presence and absence over time. In particular, it argues that high-quality access to the research field is a non-linear process, is intertwined with our researched subjects and is also regulated by institutional memory and chronopolitics, even more so in sites of policy absence.

The next section expands this argument through a reflexivity practice based on a comparative academic project of BID adoption in four town centers in England in three fundamental ways. It begins by outlining the role of positionality as the backbone of our research and how it has differently affected our angle of arrival to sites of policy presence and absence. It then moves on to discuss how the making of institutional memory mediates the nature and scale of access to a range of agencies and materialities. Finally, it concludes by introducing the notion of chronopolitics to reflect on how the intersection of politics and multiple temporalities influences our access to, and navigation through, instances of policy presence and absence.

III. Reflexive learning: researching business improvement districts' presence and absence

It has now been almost two decades since the inception of the first BID in England. Businesses in the center of Kingston upon Thames in Greater London decided to vote for the BID in 2004 and its services were initiated in 2005. BIDs have since then flourished in numerous English cities and town centers and, some would argue, changed the way they are governed. While some claim that BIDs are a new form of town center governance, their origins date back to 1970 when a group of businesses in a shopping district in Toronto, Canada, decided to pay a mandatory levy to improve the ‘quality of life’ of their area through the provision of a set of mundane services, such as cleaning, security and marketing (Kudla, 2022). However, it was in the US cities that the ‘BID movement’ found fertile ground as the ramping up of BIDs in the 1980s and 1990s show (Mitchel, 2001). Of course, some of the US BIDs and their stories have soon become seductive referencescapes that have shaped the different transatlantic futures of BIDs in the likes of Cape Town in South Africa (Didier et al., 2012), Hamburg in Germany (Michel & Stein, 2015) and Coventry or Reading in England (Cook, 2008). More recently, BIDs and BID-like institutions have also been found in wider politico-institutional contexts that are often not at the forefront of neoliberal restructurings, like Gothenburg in Sweden (Valli & Hammami, 2021) and Barcelona in Spain (Silva et al., 2022).

These and other cities and town centers are not alone. If anything, they have been brought into conversation. The research upon which the next reflections draw stems from an interest in understanding the difference that the ‘local’ context engenders in BID presence and absence. It does so through a broader relational comparative research aimed to “portray, isolate and explain the causes and consequences of similarities and differences” in the rolling-out of BIDs in different places (Mossberger, 2009, p. 45). Thus, researching comparatively contributes to unveiling the differential outcomes of urban policies in distinct contexts and draws attention to exploring the broader processes behind such policy outcomes (McFarlane, 2011; Robinson, 2015, 2022; Ward, 2010). We thus argue that it is useful to think about policy presence and absence in relational terms or, as McCann and Ward (2015, p. 829) put it, “through the absences that exist within the presences we study”. Put simply, studying instances of presence and absence are productive means through which we can extend our understanding of ‘global’ urban processes as well as produce intra- and extra-local generative knowledge to further translate policies into other contexts. By reflecting on the methodological nuances of studying sites of policy presence and absence, this article also stands as an attempt to overcome the analytic bias that has drawn the attention of much of urban policy mobility studies towards “policy presences, following what has already arrived and formed” while neglecting “sites of failure, absence and mutation” (Jacobs, 2012, p. 419).

Taking stock of the arguments conveyed in early comparative research (Kantor et al., 1997; Pierre, 2005; Tilly, 1984; Ward, 2000, 2010), in this academic project, English BIDs were theorized as formal equivalents, that is regardless of the context in which they are embedded, any BID shares the same internal characteristics, including the ballot, even though each BID displays diverse functional substratum (i.e., different modes of governance). Such a comparative reading facilitates a detailed understanding of how and why BIDs are present or absent from particular local contexts insofar as it “emphasize[s] contextual specificity, institutional diversity and the divergence of evolutionary pathways” (Brenner, 2004, p. 18) of ‘similar’ entities. In light of this, we were interested in examining the experience of both present and absent town center BIDs that have been dropped ‘off the map’ of much research in urban policy mobility while attuning to a range of aspects related to the contemporary political economy of towns centers over the years. Therefore, our case studies are English town centers that have struggled to sustain strong local economies and address issues such as economic development and socioeconomic deprivation (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government [MHCLG], 2020) (fig. 1). It is thus obvious that case-study selection was not a neutral process in the sense that not only were we confined to an already-limited set of theoretically suitable instances but also because policymaking is often encapsulated within power-laden structures that have control over what is possible to uncover and access (Cochrane & Ward, 2012). This indicates that our immersion in the research field had to be carefully negotiated and sensible to its wider politics. It is to these intricacies that this article now turns.

Negotiating, acquiring and maintaining high-quality access to the field is decisive when researching institutional arrangements such as BIDs. This was often a complicated, time-intensive and fluid process that involved numerous, and not always prolific, verbal and written exchanges with local and extra-local elites and key informants. While ‘elite’ remains a fuzzy term, we relied on Wood’s work (Woods, 1998) to theorize elites as individuals who have access to, or control over, a range of local-based resources; are socially and politically constructed as elites; are often embedded in social and professional networks; and are involved in shaping institutional agendas, often working with other stakeholders. Sticking to this definition, it was accepted that, if approached successfully, BID elites (executive directors, managers, board chairs and members of steering committees) would enable us to navigate their field more easily. While this was a quite straight endeavor in sites where BIDs existed, it proved tough and frustrating on other occasions, particularly in sites of BID absence. Building on the experiences of other qualitative researchers (Berger, 2015; Cunliffe & Alcadipani, 2016; Harvey, 2011; Mikecz, 2012; Thomas, 1995; Ward & Jones, 1999) and our own, we argue that the researcher’s positionality, which takes in personal characteristics, professional and institutional attributes as well as intellectual and ideological orientations, is reflected on the nature of the researcher-researched relationship which may affect the scale under which access to the field is given - angle of arrival - and ultimately on how research progresses. This does not mean, however, that access is an ‘absolute’ condition. Rather, gaining access from, and building rapport with, local and extra-local elites need to be understood as a process in constant making that requires self-reflexivity and perseverance, more so in instances of policy absence.

In retrospectively making sense of our research, four micro-practices that illustrate the above argument are worth highlighting. At the outset, the identification of participants involved nuanced approaches that were sensitive to the political-institutional and socio-spatial contexts of whether BIDs were established or not. In particular, it was more laborious in settings of policy absence as it was not always possible to trace a range of downloadable materials (BID business plans, brochures, feasibility studies, annual reviews, newsletters and policy briefs) whose contents would assist in assembling a list of potential interviewees and uncovering the power-laden processes and practices of policymaking (Baker & McGuirk, 2017; Freeman, 2012). Although it was fairly easy to obtain contact details - despite regular changes within BID board structures - in Great Yarmouth and Blackpool, we had to mostly draw on local and regional newspapers to locate influential individuals in sites of policy absence provided that institutional archives were eventually abandoned and made inaccessible. For instance, while in sites of policy presence we often established contact with potential interviewees through email, that was not always feasible in sites of policy absence. In such instances, we had to rely on social media screening methods for identifying and accessing ‘hard-to-reach’ individuals (King et al., 2014). These micro-practices, we argue, illustrate that researching absence requires more nuanced methodological approaches, some of which are not without ethical challenges (Cunliffe & Alcadipani, 2016).

Secondly, we relied on our institutional and intellectual backgrounds as central features to gain access to the field and build rapport with local and extra-local elites in three fundamental ways. First, in England, scholars from across the career trajectory are respected individuals who enjoy social and occupational prestige, particularly if affiliated with top-level academic universities. In light of this, and echoing early and recent qualitative research works, I strategically reshaped my identity and, thus, positionality to facilitate access to the field (Holmes, 2020; Sultana, 2007). For instance, I discursively - and seemingly successfully - represented myself as a visiting postgraduate researcher rather than a PhD student at the University of Manchester. Second, particular attention was given to aspects of transparency and wording throughout the numerous written exchanges with potential interviewees, especially in the invitation letters and accompanying ethical credentials. In doing so, we aimed to enhance the trustworthiness of the study (Harvey, 2011). Third, and finally, our academic project rested on the intellectual premise that its outcomes would inform the experimentation of the BID policy in some shopping districts in Portugal. Thus, some local and extra-local elites may have seen our study as an opportunity to mobilize their tacit knowledge that would then drive the making of urban policy futures elsewhere. These and similar micro-practices were attempts to legitimate our study among BID elites and other stakeholders and gain access to their institutions.

Thirdly, a useful, yet unplanned, tactic to gain access to, and trust from, local elites was through ‘following the meetings’ and related events that these individuals tend to attend. While much has been said about sites of exchange and learning as milieus through which policy knowledge is circulated (Baker & McGuirk, 2019; Craggs & Mahony, 2014; González, 2010; Montero, 2016), their facet as places that provide occasions for academics to meet the researched has been neglected. In light of this, we were invited to attend a two-day seminar organized by the Institute of Place Management and BID Foundation where dozens of BID representatives were showcased place activation experiences from elsewhere. In addition to such presentations, the event program included a study tour to Castlefield Viaduct in Manchester where I ended up meeting the BID manager of one of our case studies. Afterward, and in an unforeseen way, we found ourselves talking about his role and the BID structure in a Manchester bar. Thus, rather than seeing these more-or-less informal micro-spaces as unproductive for the research, we argue, they function as an opportunity through which the researcher and the researched are brought into relational proximity. As such, these places enhance familiarity and trust ties that ultimately facilitate our access to the field (Wood, 2015b).

The fourth and final micro-practice returns to the second quote with which we began the article. It has been widely acknowledged in a range of qualitative studies that privileged individuals and their institutions tend to erect a number of ‘defensibility strategies’ to condition the researcher’s angle of arrival to the field (Mikecz, 2012; Natow, 2020). Perhaps unsurprisingly we found that elites were more reluctant to talk about their experiences in sites of BID absence since the researcher is constructed as someone who will excavate ‘unsuccessful’ policymaking grounds. The following two vignettes show that a more nuanced positionality had to be (at times unsuccessfully) crafted to gain access to, and trust from, local and extra-local stakeholders in sites of policy absence. The first one comes from Wellingborough where a business owner was hesitant to talk about her BID experience. Apparently, she had faced some verbal abuse in the past. Over the course of an informal 15-minute conversation, we were straightforward about the independent nature of the study and explained its goals and conditions. In the end, we left with her the necessary ethical credentials and interview guide along with contact details. She was still unwilling to participate (fieldnotes, 13 June 2023). Two days later, she overtly responded to our questions and concluded by saying, “I’m actually glad we’ve spoken” (Interview #37, Wellingborough). The second vignette is from Tamworth and shows that access to the field may have a mutable essence over time. When we first tried to persuade a BID ‘senior figure’ in Tamworth, our access was denied. However, reflecting on the advice from other qualitative researchers (Thomas, 1995; Mikecz, 2012), we tried to capitalize on that ‘negative’ exchange by requesting access to other potential interviewees while showcasing interest in his networks. Again, our access was refused: “I’ve not worked in Tamworth for about two years now so I’m unable to assist you further” (personal communication, 13 March 2023). As interviews with other local stakeholders progressed, references to that ‘senior figure’ emerged in all of them. Sticking to the idea that studying policy absence is central to the local and inter-local politics of policymaking (McCann & Ward, 2015; Temenos & Lauermann, 2020), we mobilized a range of discursive strategies to reinforce our interest in learning from his on-the-ground knowledge by arguing that “[I]nterviews have been clear that you were a key element in the [BID] process” (personal communication, 26 May 2023). Surprisingly, we successfully scheduled an interview with that ‘senior figure’. Taking stock of these two vignettes, we argue that academics interested in local policymaking, particularly in sites of policy absence, should conceptualize their access to the field as a fluid and non-linear process that must continually attune to the ‘situated’ institutional and local politics (Cochrane & Ward, 2012; Cunliffe & Alcadipani, 2016).

The former vignette takes us to the second aspect that influences how policy mobilities researchers enter, and navigate through, their research field: Chronopolitics. In drawing our attention to a set of research micro-practices, the remainder of this article attends to how multiple and overlapping temporalities shape our way of retroactively understanding urban policymaking processes across sites of policy presence and absence (Baker & McCann, 2020; Ward, 2018; Wood, 2015a, 2015b). Four of them are discussed here. Firstly, case-study selection was explicitly limited by a set of theoretical-informed reasons, which we briefly discussed earlier, but was also sensitive to the practicalities of researching policymaking processes in situated temporalities. Such methodological approach has had implications both for studying instances of policy presence and absence. For example, Blyth, where an unsuccessful BID ballot took place in 2018, was originally one of our case studies. However, our access was refused by one of the chairs of the BID steering committee who stated that, “I’m busy with work and don’t have the time. It was so long ago I don’t have any of the paperwork now” (personal communication, 07 March 2023).

The last quote is also illustrative of a second, related, implication of how multiple and non-linear temporalities may ultimately translate into distinct levels of access to the research field. Essentially, the argument here is that it is critical to consider the role of institutional memory in the study of policy presence and absence in three fundamental ways. A first micro-practice that we attuned to was that of materialities. Returning to the last quote, it becomes evident that personal and institutional archives (electronic and paper-based) are useful to make sense of how policy knowledge was assembled and circulated over time. While a significant proportion of urban historians and historical geographers have long incorporated several archival sources into their work, urban policy mobilities scholars have only recently considered their benefits (Cook et al., 2014; Wood, 2015a). In light of this, following and accessing the materials (business plans, consultancy reports, meeting minutes, newspapers and policy briefs) can offer new and complementary ways through which recent as well as the more distant past policy knowledge has become thinkable and actionable (Baker & McGuirk, 2017; Roche, 2010). However, the use of archives is not without technical and intellectual challenges. The former encompasses, for example, issues related to access to these materials, more so in sites of policy absence. In such instances, our complete and unbiased understanding of urban policymaking processes was occasionally undermined by episodes of ‘institutional amnesia’ in the sense that institutional archives were often made inaccessible, abandoned or even destroyed (Stark & Head, 2019). The role of electronic and library archivists was thus fundamental in getting access to relevant materials produced by different agencies and institutions. The intellectual challenges are often related to the power-laden intricacies inherent in still-existing materialities both in sites of policy presence and absence. There is a need to excavate the ‘black box’ of the multiple and often deliberate ‘silences of the archives’ to avoid fragmented and partial insights into urban policymaking processes (Thomas et al., 2017). As one interviewee recalled, “What you are showing me [business plan] is only the [BID] budget proposal; it is not the actual BID expenditure, which, I believe, was different (Interview #39, Wellingborough). To address some of these concerns, a second, paired, micro-practice is that of considering the tacit knowledge of human agencies involved in urban policymaking processes and its resonance in institutional memory. While policy actors often draw upon materialities to generate and translate policy knowledge, our research expands this idea by arguing that institutional memory is a lively process that inhabits as much in temporal-contingent documents as in reflexive learning practices of those involved in policymaking (Corbett et al., 2020; van Wijk & Fischhendler, 2022). Practically speaking, we relied on semi-structured interviews in which individuals were asked to recast memories and interpret and reflect on their decisions and experiences to further inform policy futures. As one interviewee put it, “If I could rewind the clock and do it differently, I think I would have focused [the BID area] on the town center and town center only” (Interview #50, Tamworth). This quote is indicative of a further resonance of institutional memory for urban policy mobility studies as it sheds light on how learning opportunities can emerge out of places of policy absence.

Thirdly, our research practice calls for the need to critically reflect on the transient and fluid nature of local politics and the range of stakeholders involved in them. In particular, we found that chronopolitics have influenced the extent through which local and extra-local actors could be identified, accessed and ultimately tailored to provide useful temporal trails of local policymaking processes, especially in sites and situations where their immersion was transitory. This learning lesson has relevant practical consequences both in sites of policy presence and absence in similar ways. One of them becomes evident when researchers are directing their attention towards understanding multi-lateral and multi-temporal processes of policy circulation and adoption by relying on ‘on-the-ground’ knowledge of those involved in such arenas. In light of this, identifying and recruiting suitable local policy and social actors can become a methodological challenge in the sense that the nature of their immersion in policymaking processes is path-dependent and often made of multiple ‘starts’ and ‘stops’. We found that such ephemeral experiences of learning and ‘doing’ have implications for the differential thickness of situated knowledge that we can ultimately obtain. Thus, and perhaps unsurprisingly, it became evident during the interviews that a BID executive who has been in the position for no more than two years tended to provide vaguer and ‘before my time’ type of answers than a two-decade veteran BID executive. A second, related, aspect is intertwined with the practices of tracing the local and extra-local actors involved in circulating and implementing urban policies on multiple occasions. In some of them, it turned out that ‘time’ and multiple temporalities have become barriers to accessing a set of potential well-placed BID insiders and other informants. This was particularly noticed in areas where the business structure has proven to be less resilient and where relevant stakeholders have only been involved transitorily in policy adoption and have since then moved to other positions (Robin & Nkula-Wenz, 2020; Wood, 2015b). Though the former examples are insightful on their own, a final outstanding instance to illustrate the role of chronopolitics in urban policy mobility research lies behind the ‘shifting’ and complex local politics that shape how policies are rendered mobile (present) or immobile (absent) over different temporalities. Shedding light on the knock-on effects on town center governance of the recent UK local government reform, one interviewee argued that:

Those things [town center plans] haven’t been forgotten (…) but they had to take a back seat while we implement local government reform because doing all the restructures and desegregation of the county has taken up so much time. Plus, we also lost people [officers] (…) With that, you lose experience and knowledge. (Interview #35, Wellingborough)

Fourthly, and finally, we argue that attending to the temporality and non-linearity of policymaking processes can shed light onto the generative knowledge that may be engendered over different ‘times’, particularly so in sites of absence. Translating this notion into a set of research practices has at least three consequences for urban policy mobility research. First, it will require refinement in the use of historiographic methods and primary sources, such as personal and institutional archives (Roche, 2010; Wood, 2015a). Second, it will elucidate the processes through which some urban policies may be rendered mobile and then canceled in different politico-institutional, socio-spatial and temporal contexts. Third, and building on recent debates (Baker & Temenos, 2015; McCann & Ward, 2015; Robin & Nkula-Wenz, 2020), it will contribute to understanding ‘absence’ not as a discrete condition but through relational means that can engender “rounds of reform within … political and institutional parameters” (Brenner et al., 2010, p. 333). The first quote with which we began this article is indicative of how policy absence was intellectualized in our academic project. Rather than seeing it as a fruitless outcome, we argue that researching such instances elicits tacit knowledge that can serve as a shot of caffeine in reshaping the contours of policymaking decisions not only in former sites of policy absence but also in places thinking about reinventing their urban policy futures.

IV. Conclusion

In concluding, it is useful to return to the two quotes with which we began the article. While each of them was voiced by stakeholders with distinct positions in urban politics, both implicitly speak to the broad aim of this article by sharing a common understanding of the differential practical issues of conducting comparative research in sites and situations of policy presence and absence. In the first quote, a business owner reasoned that instances of policy absence can have generative ramifications. More fundamentally, she draws our attention to the importance of attending to the multiple and non-linear temporalities when researching urban politics and policymaking processes. Doing that, she suggested, is instrumental in exploring how sites of policy absence can, often in unexpected ways, influence the reinvention of urban policy futures. In the second quote, one senior BID director implicitly acknowledged the influential role that (at times crafted) positionality can perform in the ways we are given or refused access to the research field.

This article has drawn on urban policy mobility debates to advance the wider, yet still limited, discussions on the practical issues and implications that those interested in studying local policymaking through comparative gestures should consider during their research. The arguments that have been offered in this article are informed by the debates of ‘thinking through dualisms’ within urban policy mobility literature (Baker & Temenos, 2015; McCann & Ward, 2015). Building upon this still-emerging body of geographical literature, this article stands as an invitation to examine sites of policy presence and absence in mutually constitutive terms, that is thinking through policy absences within the ‘actual existing’ policies we study. Sticking to this ontological idea and building upon recent debates (Jacobs, 2012; Robinson, 2015, 2022), the article has attempted to unravel and, in some cases, expand our practical understanding of broader urban policymaking processes. It has done so by bringing into methodological conversation sites where policies have been formed and rolled out along with sites of policy rejection, de-activation and absence. In particular, this article has used a set of qualitative research methods studies as well as our multi-sited research experience on the adoption of BIDs in different English town centers as a gateway to problematize and reflect on some of the methodological challenges of accessing and navigating through sites of policy presence and absence. In so doing, it provided possible tactics for facilitating our immersion in such policymaking landscapes.

The reflexive reading of our research practices has demonstrated the value of attending to issues of researcher’s positionality, institutional memory and chronopolitics when conducting comparative research within and between sites of policy presence and sites of policy absence. First, the article has illuminated that gaining access from, and building rapport with, local and extra-local elites are non-linear and fluid processes and must continually attune to the ‘situated’ local politics, which are often more complex in sites of policy absence. Our nuanced positionality influenced our angle of arrival to the research field and was fundamental to overcoming such challenges, particularly in settings where turbulent institutional and politics prevail. For instance, we made tactical use of our institutional and intellectual backgrounds, carefully assembled discursive strategies and attended temporary learning events to enhance empathy, familiarity and trust ties as well as legitimate our academic project among BID elites and other local and extra-local stakeholders. In doing so, we positioned ourselves as “insiders” and scholars interested in learning from instances of both policy presence and absence.

Second, the article has highlighted the influential role of institutional memory in the nature and scale of our access to the research field as well as the thickness of the evidence obtained. In particular, it has argued that institutional memory is a lively process that inhabits as much in temporal-contingent materialities as in reflexive learning practices of those involved in policymaking. While in instances of policy presence access to these materials and individuals was a relatively simple process, in sites of policy absence our impartial, complete and unbiased understanding of policymaking processes was occasionally undermined by episodes of ‘institutional amnesia’ provided that personal and institutional archives were discontinued, made inaccessible and destroyed (Stark & Head, 2019).

Third, and finally, the article has emphasized the benefits of attuning to the wider local chronopolitics to argue that ephemerality and transitoriness are axiomatic aspects of urban politics and policymaking processes. These attributes suggest that our understanding of such processes and their path dependencies should consider how longitudinal shifts in political-institutional settings, including the policy and social actors involved in them, can influence our access to, and navigation through, as well as the thickness of the situated (at times generative) knowledge that we can obtain from the research field. In terms of methodological praxis, these arguments and their associated micro-practices make two deliberate contributions to the wider methodological debates on urban policy mobilities. One of them is to expand the nuanced implications of studying comparatively urban policymaking processes across sites of presence and absence in different temporalities. The other is to advocate that qualitative researchers, in general, and urban policy mobility scholars, in particular, while acknowledging their positionality, should not overlook institutional memory and chronopolitics as lower-level concepts that regulate their angle of arrival to the research field and ultimately research outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. (Ref. 2020.06080.BD). I would like to acknowledge the support of the editors of Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia and anonymous referees for their supportive comments which greatly contributed to improving my arguments. I further acknowledge all those with whom I spoke as part of my research program at The University of Manchester upon which this article draws. A special thanks to Kevin Ward for commenting on the earlier draft of this article. The usual disclaimers apply.