Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

Print version ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.104 Lisboa Apr. 2017

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis6969

COMENTÁRIO

Environmental mediation: an instrument for collaborative decision making in territorial planning

Mediação ambiental: um instrumento de apoio à decisão colaborativa no âmbito do ordenamento do território

Mediation environnementale: un outil pou aider aux decisions collectives relatives a lamenagement du territoire

Ursula Caser1; Cátia Marques Cebola2; Lia Vasconcelos3; Filipa Ferro4

1European Master in Mediation and Dipl. Geographer, Researcher of MARE – Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre and TUM MCTS – Munich Center for Technology in Society and CEO of Mediatedomain, Lda. Address: Rua Nery Delgado 9-1, 2775 253 Parede, Portugal. E mail: ursicaser@gmail.com

2Associate Professor at ESTG – Polytechnic Institute of Leiria and Director of the Research Centre on Legal Studies (CIEJ) – IPLeiria. Address: Campus 2 – Morro do Lena – Alto do Vieiro, Apartado 4163, 2411 901 Leiria, Portugal. E mail: catia.cebola@ipleiria.pt

3Assistant Professor at UNL - New University of Lisbon, Researcher of MARE - Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre and Coordinator of MARE Thematic Research Line in Policy and Governance. Address: Campus of Caparica, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal. E-mail: ltv@fct.unl.pt

4Master in Environmental Engineering, Project Manager at Mediatedomain, Lda. and Researcher of MARE – Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre. Address: Rua Nery Delgado 9-1, 2775 253 Parede, Portugal. E-mail: filipa.ferro.5@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Environmental Mediation allows, besides formal participation, true collaborative decision making as well as prevention and resolution of conflicts. This paper analyses the advantages of mediation applied in environmental and territorial planning conflicts (Mediação Ambiental e Sócio-Territorial - MAST) following the requirements of the Portuguese Mediation Law No 29/2013, of April 19th. It aims to understand if this legal basis prevents or encourages a more intense and efficient use of Environmental Mediation in land use planning as a means within public policy.

Keywords: Conflict; mediation; land use; territorial planning; mediation law (Law No 29/2013, of April 19th).

RESUMO

A Mediação Ambiental permite, além da participação formal dos interessados, um verdadeiro processo de decisão colaborativa, constituindo ainda um meio de prevenção e resolução de conflitos. O presente trabalho analisa as vantagens da mediação aplicada a conflitos ambientais e de planeamento territorial (Mediação Ambiental e Sócio-Territorial - MAST). Face à publicação da Lei de Mediação em Portugal n.º 29/2013, de 19 de Abril, importa perceber se esta base legal impede ou possibilita a aplicação da MAST no ordenamento jurídico português e em que termos.

Palavras-chave: Conflito; mediação; ordenamento do território; planeamento territorial; lei de mediação (Lei n.º 29/2013, de 19 de Abril).

RÉSUMÉ

Une nouvelle loi de médiation, Mediação Ambiental e Socio-Territorial - MAST (Nº 29/2013,19 Avril). Lá présente étude analyse ses avantages et ses inconvénients, dans le cadre de la prévention et de la résolution des conflits résultant de la planification territoriale au Portugal.

Mots clés: Conflit; médiation; aménagement du territoire; loi de médiation (Lei nº 29/2013, de 19 de Abril).

I. INTRODUCTION

Environmental Mediation allows, in addition to formal participation, true collaborative decision making as well as the prevention and resolution of conflicts, through the involvement of all stakeholders in territorial planning and urban design. Mediation on environmental issues is based on the idea that all available knowledge (technical and non-technical), from all parts of society should be integrated in decision-making processes to guarantee that the chosen projects and development plans reflect best possible ideas and interests for the future users.

As referred to by Susskind and Weinstein (1980), Environmental disputes, in particular, are characterized by their scientific and technical content. Judges, lawyers, and government officials routinely encounter questions involving the most sophisticated concepts in such disciplines as statistics, demographics, limnology (the study of bodies of fresh water), radiology, public health, and more. Even the most conscientious among them cannot hope to grasp more than broad dimensions of a given case. The authors added that The ability of the courts to deal with polycentric problems – problems in which a large number of results are possible and many interests and values are involved – has long been questioned and that environmental disputes are just such problems and often exceed the decision-making capacity of the courts (Susskind & Weinstein, 1980).

In the jurisdictional field, the Directive 2008/52/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial matters imposed the regulation of mediation in all Member States. In Portugal, the mediation is now regulated by Law No 29/2013, of April 19th, whose principles, according to Article 3, are generally applicable to any mediation in Portugal.

In this paper we provide insight into the process of Environmental Mediation and discuss how the Portuguese Law on Mediation (Law No 29/2013, of April 19th) may encourage (or not) a more intense and efficient use of Environmental Mediation in land use planning as a means for public policy.

II. ENVIRONMENTAL MEDIATION

1. Territorial planning

1.1. Conflicts in territorial planning

The principle of coordination provided in the National Programme on Spatial Planning Policy (PNPOT)i states that there should be an appropriate balance of public and private interests in spatial planning. In practice there are naturally a variety of adverse ideas and attitudes between stakeholders from civil society and from the public and private sectors, and as well from local or central governments (Castro e Almeida & Caser, 2012). Conflicting positions, interests and needs are manifold, as can be seen from a set of illustrative examples revealing the origins of conflicts:

- economic growth versus conservation of nature;

- tradition versus innovation;

- technical knowledge versus local livelihood knowledge;

- institutional interests versus individual interests;

- complex interdependencies in an environment of multiple uncertainties;

- highly dynamic development processes or social topics to handle;

- imponderables of eventually involved risks and potential trade-offs.

Obviously all these complex distinct positions, resulting from different views of the world, give room to highly diverging political, economic, social, environmental, and moreover, guide decision options. As these contexts for planning and decision making show great complexity, conflict is frequently a constant. Therefore, there is an enormous demand for competent and efficient conflict management and the requirement to include the institutionalised stakeholders from the public and private sectors. Additionally, it is paramount to also bring to the process the perspectives and interests of the future users, the citizensii.

Quite often the use of the same resource for different purposes creates incompatibility of usage in the same space. For example, in the Marine Park of Arrábida fishermen want to use the space for fishing, maritime-touristic activities for visits and park managers for conservation. If the three users do not come to an agreement of its usage, by delimitating the spaces for different activities or agreeing on a schedule of usage, conflict emerges.

1.2. Public Participation - The Involvement of Civil Society

In order to promote sustainable territorial planning and urban development, simultaneously bearing in mind that the citizens should have their say as they are the targets of the territorial policy decisions and the final users, public participation has become increasingly mandatory by the requirements of planning laws. Building on a philosophy that involves different technical experts as well as the civil society in territorial planning, Participation became a magic word, suddenly heard all around. However, hope turned into frustration in many cases. What had happened? Participation was understood by the planning authorities as convening meetings with planners, experts and citizens in traditional formats, where the technical experts present their ideas to public scrutiny and approval (or even: the already nearly consolidated plan) and open the debate to citizens in an auditorium – in a merely consultation format. People are welcome to agree or disagree with what is presented. When the document presented involves controversial issues, it has the merit of bringing to the public audition those against the proposal. In this setting, quite often conflicts may emerge, leading to the generation of myths and fears on the part of the technicians and decision makers against wider decision making involvement (Caser, 2009). When this happens, public participation is seen as overly critical by municipalities and central government authorities.

One of the most important lessons learnt is that successful participation processes have to be professionally designed and facilitated. For this to happen they must involve the civil society from the very beginning of the planning process, when ideas can be discussed, challenged and worked on, and before decisions are already taken. Of course, inconvenient decisions will never be pacific and consensual (i.e., airport construction, location of waste treatment plants, etc.) so conflict is and will always be a natural phenomenon in territorial planning. To promote long lasting and sustainable decision making, mediation is a promising instrument to prevent, mitigate, address and resolve territorial conflicts in a more constructive way. In mediation, stakeholders are not seen as passive consumers but they are an active part of the planning and implementation process (Carvalho-Ribeiro, Lovett, & ORiordan, 2010). As such, they contribute genuinely with their knowledge, are part of the process of conflict resolution and share responsibilities for the decisions taken and chosen solutions (Lang et al., 2012).

Overcoming the conflict and being able to create dialogue among the parts is one of the functions of mediation that can lead to more successful results of wider participation. Moreover, a continuous process where stakeholders are truly part of the process, phased and structured, can offer promising results as shown by the MARGov Project (Vasconcelos, Caser, Pereira, Gonçalves, & Sá, 2012; Vasconcelos, et al., 2013; Cebola, Caser, & Vasconcelos, 2014).

1.3. Management and conflict resolution presently

The Law No 19/2014, April 14th, which sets out the basis of environmental policy in Portugal, does not provide any extrajudicial mechanism of dispute resolution in environmental matters. This law was under discussion but Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) processes were not a strong issue in the debate. Except for the Bloco de Esquerda (BE), all other political parties have excluded the introduction of environmental ADR in their proposals and the final document kept silent on this matter.

Despite the inexistence of a specific legal rule with respect to and governing the implementation of mediation in environmental issues, one of the basic principles of environmental legislation is based on the right of participation of citizens in several environmental decisions. In fact, the principle of participation is described by the Law on Policy Planning and Urbanismiii and in the Legal Framework of Land Management Instruments (RJIGT)iv.

Realising this principle, the Legal Framework of Land Management Instruments establishes an intervention phase by citizens in the development of all urban plansv and the Law on Policy Planning and Urbanism prescribes that the development and adoption of binding land management instruments are subject to enhanced mechanisms for citizens participation, particularly through forms of concerted interests.

These legal documents appeal, therefore, to the concertation of private and public interests. As Oliveira and Lopes (2003) state: concertation is a qualified form of participation, which requires the dialogue to be extended to the search for commitment and mutually acceptable solutions to all parties.

Thus, we believe that the best way to implement the principle of participation enshrined in the law and the inherent interest of concertation will be through the implementation of mediation on conflict resolution, as well as on urban planning, providing, in this case, a form of conflict prevention.

The implementation of environmental mediation as a mechanism for citizens participation in environmental decision-making is crucial, since participation increases the acceptability of the public decisions and promotes the accountability of the community (Gomes, 2009).

2. Environmental Mediation - a methodology for structured conflict management and resolution

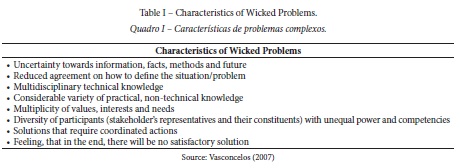

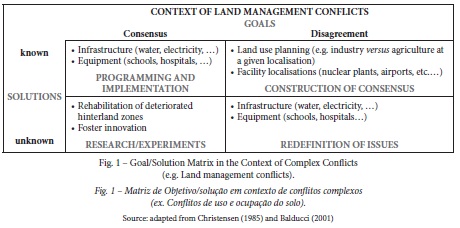

The choice of mediation (or mediated negotiations) is especially recommendable in a context of wicked problems (Rittel & Weber, 1973) and in environments where disagreements on goals combined with the existence of many technical solutions originate discussion and conflict. Wicked problems are characterised by complex interdependencies where the resolution of one aspect usually creates new challenges. Table I shows a compilation of the key challenges associated with wicked problems that fall in the above-right category of the goal/solution matrix (fig. 1).

In these environments a structured process of consensus construction - mediation - is most likely to lead to sustainable solutions that best serve the interests and needs of all involved stakeholders. When there is a genuine inclusive dialogue process involving the multiple stakeholders in these complex contexts, the chances for success increase (Wiegand, 2014). For example, the case of the MARGov project that carried out such a process, based on a spinal cord of open forums out of which a core group emerged, willing to carry on the process further. This group, which had been previously involved in most of the forums, did not stop working together to get to consensual rules of management for the marine park. The new strategic council for the Marine Park created in 2015 invited this group to become the consulting Group of the Sea attributing it a mandate.

2.1. How does Mediation work?

Mediation is a process of direct negotiation between actorsvi, which is assisted by one or more professionally trained mediators. The mediators are responsible for creating a conversational arena where participants can educate each other on their perspectives and values, identify common, compatible and conflicting interests and needs and search collaboratively options for solution (Moore, 2003). Any decision is taken by the stakeholders, the mediator must not have any personal or professional interest in the outcome or any decision making power (see also in this text III below).

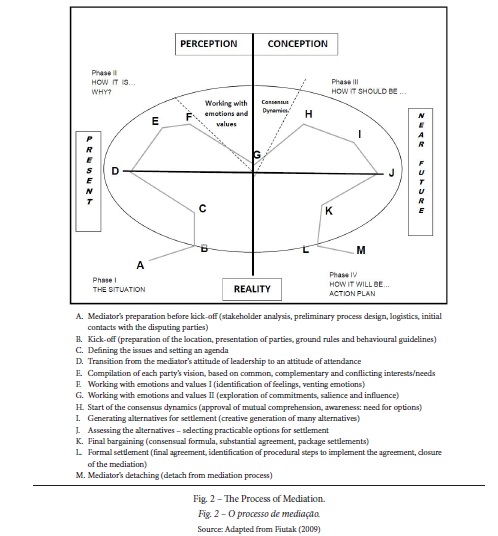

The mediation procedure can be divided largely into 13 phases (fig. 2):

The process designed above also demonstrates the advantages of mediation in power imbalance situations, so common in environmental and territorial conflicts. In fact, an environmental or territorial conflict may involve citizens, private entities with economic or social goals and public and government entities, which is quite revealing of the different power forces in conflict. The mediation process and methodology, based on dialogue and equal treatment of the parties, can mitigate the existing power imbalances. The mediators impartiality and neutrality principles consolidate mediation as a balancing arena. The mediator has the task of putting all the parties interests at the same level, using convenient methodologies, techniques and instruments. Empowerment of weaker stakeholders and creating a power balance between involved parties attest to the advantages of mediation in resolving environmental conflicts.

2.2. European Examples of the MAST

The implementation of mediation is starting to have an increased adherence and implementation in the resolution of environmental conflicts. Next we give a quick insight into specific cases.

In European terms, IMPEL (European Union Network for the Implementation and Enforcement of Environmental Law) has undertaken, in 2004, the project "Informal Resolution of Environmental Conflict by Neighborhood Dialogue", which is born out of an experience in Hannover, Germany. In fact, the German Department of Labour and Environmental Inspection implements, since 1995, the dialogue between neighbours and several industrial companies in resolving environmental conflicts.

In this context, IMPEL has developed a practical guide (toolkit) to disclose the referred project that would, simultaneously, support the authorities and companies in the implementation of guidelines and techniques to promote dialogue with the stakeholders in conflictvii. The purpose of IMPEL is based on the methodological premises of mediation.

The IMPEL's project was implemented in Germany in a specific conflict that emerged between a citys population and a steel factory (ThyssenKrupp Nirosta), because of the limestone dust emission produced by this company. In 2005, the inspection authority convinced the factory representatives to engage in a dialogue with local residents. It was the company itself that hired a professional facilitator to assess the possibility of a dialogue with the population, which began in May 2006. A group of interconnection (Kontaktgruppe) was created and deemed responsible for the preparation of meetings between all involved stakeholders. After a year and a half of dialogue implementation, relations between neighbours and factory representatives had improved and the level of distrust towards the companys actions had declined substantially (Schüpphaus, 2007).

In Portugal, this process was also successfully applied, namely in a conflict related with emissions of fumes and odours by a company that produced pulp paper. Through dialogue, the conflict was resolved, and the company provided the use of its own wastewater treatment plant for water treatment of the urban population (Cebola, 2010b).

Within the territorial conflicts in Norway, mediation has being playing an essential role in resolving boundary disputes (Sky, 2003). In this type of conflict, the parties could disagree about how maintenance costs should be split, the standard to which the road should be maintained, how much it should cost to buy a right to use the road, etc. The mediation process allows for dispute resolutions with a great variety of solutions to a problem. In 1996, mediation helped solve approx. 43% of boundary line disputes at the land consolidation courts (Sky, 2003).

In Portugal, so far there has not been any explicitly declared environmental mediation, but, for example, the above mentioned process MARGov, focused on the engagement of stakeholders in dialogue in a conflict context, aiming to achieve an agreement between parts in conflict on the management rules for the marine park of Arrábida (e.g. artisan fishermen and the managers).

III. LEGAL ADMISSIBILITY OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIO TERRITORIAL MEDIATION (MAST)

1. The Portuguese Mediation Law - general framework

In order to transpose the Directive 2008/52/EU, in 2009, Portugal introduced a few legal rules in the Civil Procedure Code, with the objective of regulating the essential aspects of mediation in our country (Cebola, 2010a). However, this legal transposition left out some important questions, such as the professional status of the mediator or the regulation of the private mediation (Gouveia, 2010; Morais, 2011; Schmidt, 2013).

Therefore, to increase the implementation of mediation, an autonomous and specific mediation law was promulgated in 2013 (Law No 29/2013, of April 19th)viii that covers four important questions:

- the general principles applicable to every mediation held in Portugal;

- specific rules of civil and commercial mediation;

- the mediators professional status;

- the principles that regulate in general the public mediation systems.

Next we will give an account of how this new law may encourage the application of the MAST in Portugal, or even if the MAST is allowed by this new legal framework.

2. The MAST implementation in the Portuguese legal system

The Law No 29/2013 does not establish a general criterion for conflicts that could be submitted to mediation. Indeed, in its general provisions, this law, in Article 2, merely defines mediation as a means for alternative dispute resolution, carried out by public or private entities, through which two or more parties in a dispute voluntarily try to achieve an agreement with the assistance of a mediator. The Law does not, therefore, refer to any limitation or scope.

On the other hand, the Law No 29/2013, in Article 11, just establishes limits regarding conflicts in civil and commercial matters. Consequently, this new law does not expressis verbis preclude the implementation of mediation to public conflicts, or more specifically to environmental conflicts. However, it also does not make reference to them.

With regard to private environmental conflicts (e.g. water easements, easements boundaries, tree planting), no obstacle stands up to the application of mediation. In any case, a private mediator can be hired to help the conflicting parties - through genuine dialogue - to try and find a solution to their conflict.

Regarding conflicts involving public entities, doubts concerning the implementation of mediation can be raised as in many conflicts an administrative decision is needed.

However, as mentioned earlier in this study, the participation of citizens and other stakeholders in decision-making processes of public bodies is a constant principle in administrative and environmental law. Thus, as a mediation law exists, which regulates the general action of mediators in Portugal, their intervention could also be legitimised in the context of environmental conflicts in order to implement the legally required principle of participation, particularly when it comes to land use plans.

We must highlight that the laws recently approved on the environmental fieldix stress the importance of concertation and participation which justified our position. In fact, mediation may be the best, if not the only way to put all stakeholders involved in environmental questions in dialogue in order to achieve the required principle of participation and concertation. Otherwise, the public discussion of environmental issues may lead to an empty space of opinions without reaching constructive contributions.

The MARGov project, for instance, proves that factx. This project intended to implement a Model of Collaborative Governance in Arrábida Marine Park Professor Luiz Saldanha (MPLS). The creation of a Marine Protected Area (MPA) in this Park led to usage restrictions and hence towards conflicts between the affected stakeholders. A public discussion period existed before the creation of the restricted areas. Even so, stakeholders felt they had not been heard and the conflictual situation was only overcome after the intervention of a mediating team (Vasconcelos et al., 2011a; Vasconcelos et al., 2011b).

Without mediation, the public discussion period becomes a mere collection of opinions, with no dialogue between the stakeholders in order to transform the isolated proposals into a joint solution to resolve the conflict. That is why we advocate the implementation of mediation as a way to achieve the required participation prescribed in recent environmental laws above mentioned.

3. The (environmental) mediator in the new law

So far the profession conflict mediator is not a protected designation, neither in Portugal, or worldwide. The mediator assumes themself as a new type of professional who provides his or her services independently and impartially.

The Law No 29/2013 establishes rights and duties of the mediator, whose action has a legal regulation that legitimises his or her intervention, which will be essential to provide a communication channel between citizens and public authorities.

To be a professional conflict mediator personal characteristics are important as well as a highly competent intervention. Although the profession mediator is not protected so far, for certification a sound training is recommended by national and international mediators associationsxi. In Portugal - especially for being a mediator in the public sector - an academic course is required (which can be practically any) as well as the attendance of a course on conflict mediation (the training institute has to be certified by the Portuguese Ministry of Justice).

To act as a conflict mediator in environmental conflicts or in processes of public participation, no official requirements exist at all (so far). Anybody can declare themself a mediator and conduct mediations or consensus construction processes. Standards and certifications are required to be developed to guarantee the specific competence of environmental mediators and the quality of their intervention.

IV. RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Recommendation to public services responsible for spatial planning

When defining a new vision for land use planning, the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI, 2001) emphasises that mediation should be implemented in all planning processes, as spatial planning is characterised by the constant presence of competing interests, particularly with regard to land use and different goals in the short and long run.

We support this idea, as without a sound conflict management strategy, conflict might bear incommensurable risks - especially in the actual context of financial crisis. Interested stakeholders demand more and more to be effectively considered in decision making, and they have a legitimate right to have their say. As actors are diverse and disorganised and no clear rules and procedures exist to steer multi-stakeholder dialogues or resolve conflicts (Putnam & Wondolleck, 2003), central and local governments are asked to invest in a professional handling of these situations, where interests and values involved are manifold, the number of interested parties is considerably high, the amount of issues under discussion grows and conflict and the cost of the resolution constantly increasing.

According to the requirements for a successful process of conflict resolution it is absolutely crucial that the parts in conflict hand over the mediation role to a third party viewed as independent. Therefore, in this context, it is crucial that the central, regional and local governments or public institutions understand that they should hand over the mediator role. Moreover, usually public servants do not have methodological competence to design and conduct these types of processes, but the uttermost important argument against their intervention as a mediator, in contexts of conflict, is that they as a member (or even as a representative) of one of the powerful stakeholders have a genuine self-interest in the outcome, and - of course - are not at all seen as neutral and independent interveners by the majority of private institutionalised or individual stakeholders (Caser & Vasconcelos, 2012).

2. Recommendations to the lawmaker

The advantages of implementing mediation in environmental and territorial conflicts should receive special attention from the legislator.

In this context, a Law on mediation in public issues should be published, including environmental matters, in order to create the necessary legal framework for the implementation of the MAST in Portugal and consequently allow public entities and citizens to collaborate and reach consensus about the decisions that concern them (Cebola, 2010b).

On the other hand, mediator training should be made mandatory. The training has to be provided by recognised competent experts that already work in the field. Training that offers a specialisation in environmental issues should give way to the elaboration of a list of specialised mediators whose services would be used by citizens and also entities when faced with an environmental or land use conflict.

V. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

In this paper we demonstrated that the MAST offers public bodies, citizens and private companies operating in a given area, a complementary solution to judicial or civil protest, ensuring that all the parties feel co-responsible and part of decisions taken. Mediation outcomes reflect all stakeholders aspirations, interests and needs. In a context of austerity and crisis, where public money is scarce, early consensus building can save time, financial and human resources and contributes to more sustainable spatial planning with a potentially smooth implementation of the decisions taken.

We have presented some effective experiences that showed how mediation can transform the conflict into a dialogue arena where all stakeholders can intervene and create the best collective solution to address the conflict. In this way, mediation can increase the acceptability of the final decision.

We described here the process of mediation in detail. Obviously, however, mediation is not the one and only process for best decision making and conflict resolution in all complex situations, but if the process is professionally professionally (well) conducted, mediation is enormously powerful to solve planning issues and land use conflicts in a sustainable way. The tangible consensus based results like formal settlements, action plans or management models, together with the great variety of intangible social results contribute to create participative co-responsible societies and social peace.

Despite these successful examples, environmental and territorial planning mediation has still not attracted the legislators attention. However, the existent legal framework does not preclude the implementation of mediation to environmental and territorial conflicts.

REFERENCES

Balducci, J. (2001). Complex Problems. Not published, Departamento de Ciências e Engenharia do Ambiente da Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. [ Links ]

Carvalho-Ribeiro, S. M., Lovett, A., & O'Riordan, T. (2010). Multifunctional forest management in Northern Portugal: Moving from scenarios to governance for sustainable development. Land Use Policy, 27(4), 1111-1122. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.02.008. [ Links ]

Caser, U. (2009). Socio-Environmental Mediation: Myths and Fears. Revista de Estudos Universitários, 35(2), 67-83. [ Links ]

Caser, U., & Vasconcelos, L. (2012). A Mediação Ambiental e Sócio-Territorial (MAST) - Um Campo de Intervenção por Excelência para Geógrafos! [Environmental and Socio-Territorial Mediation (MAST) - A Field of Intervention for Excellence for Geographers!]. Revista de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território, 2, 75-96. doi: 10.17127/got/2012.2.004. [ Links ]

Castro e Almeida, J., & Caser, U. (2012, outubro). A Mediação de Conflitos no Planeamento do Território em Portugal [The Mediation of Conflicts in Territory Planning in Portugal]. In III International Congress on Mediation - Mediation and Arbitration. Conducted at the Centre for Public Administration and Public Policies (CAPP) of the School of Social and Political Sciences (ISCSP), Technical University of Lisbon (UTL), Lisbon, PT.

Cebola, C. M. (2010a). A mediação pré-judicial em Portugal: Análise do novo regime jurídico [Pre-judicial mediation in Portugal: Analysis of the new legal regime]. [electronic version]. Revista da Ordem dos Advogados, 70(I/IV), 441-459. Retrieved from: http://portal.oa.pt/comunicacao/publicacoes/revista/ano-2010/ano-70-vol-iiv-2010/doutrina/catia-marques-cebola-a-mediacao-pre-judicial-em-portugal-anaali se-do-novo-regime-juridico/ [ Links ]

Cebola, C. M. (2010b). Da admissibilidade de meios extrajudiciais de resolução de conflitos em matéria ambiental e urbanística - experiências presentes, possibilidades futuras [The admissibility of extrajudicial means of conflict resolution in environmental and urban matters - present experiences, future possibilities]. RevCEDOUA - Revista do Centro de Estudos de Direito do Ordenamento, do Urbanismo e do Ambiente, 25, 65-84. [ Links ]

Cebola, C. M., Caser, U., & Vasconcelos, L. (2014). La confidencialidad en mediación ambiental. Su aplicación al Proyecto MARGov en Portugal [Confidentiality in environmental mediation. Its application to the MARGov Project in Portugal]. [electronic version]. La Trama - Revista Interdisciplinaria de Mediación y Resolución, 41, 1-22. Retrieved from: http://www.revistalatrama.com.ar/contenidos/larevista_tapa_anterior.php?id=41 [ Links ]

Christensen, K. (1985). Coping with Uncertainty in Planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 51(1), 63-73. doi: 10.1080/01944368508976801. [ Links ]

Fiutak, T., Planès G., & Colin Y. (2009). Le médiateur dans l'arène: Réflexion sur l'art de la médiation [The mediator in the arena: Reflection on the art of mediation]. Toulouse: Éditions érès. [ Links ]

Gomes, C. A. (2009). Participação pública e defesa do ambiente: um silêncio crescentemente ensurdecedor [Public participation and environmental protection: an increasingly deafening silence]. Monólogo com jurisprudência em fundo. Cadernos de Justiça Administrativa, 77, 3-15.

Gouveia, M. F. (2010). Algumas questões jurídicas a propósito da mediação [Some legal issues regarding mediation] In J. Vasconcelos-Sousa (Ed.), Mediação e criação de consensos: os novos instrumentos de empoderamento do cidadão na União Europeia [Mediation and consensus building: the new instruments for citizen empowerment in the European Union] (pp. 213-242). Coimbra: Ed. Minerva. [ Links ]

Gouveia, M. F. (2014). Curso de Resolução Alternativa de Litígios [Alternative Dispute Resolution Course]. (3rd ed.). Coimbra: Ed. Almedina. [ Links ]

Gualini, E. (2015). Planning and Conflict: Critical Perspectives on Contentious Urban Developments. New York and London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Lang, D. J., Wiek, A., Bergmann, M., Stauffacher, M., Martens, P., Moll, P Thomas, C. J. (2012). Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science, 7(SUPPL.1), 24-43. doi: 10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x. [ Links ]

Lopes, D., & Patrão, A. (2016). Lei da Mediação Comentada [Commented Mediation Law]. (2nd ed.). Coimbra: Ed. Almedina. [ Links ]

Moore, C. (2003). The Mediation Process - Practical Strategies for Resolving Conflict (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Morais, J. C. (2011). A consagração legal da mediação em Portugal [The legal consecration of mediation in Portugal]. Julgar, 15, 271-290. Retrieved from: http://julgar.pt/a-consagracao-legal-da-mediacao-em-portugal [ Links ]

Oliveira, F. P., & Lopes, D. (2003). O papel dos privados no planeamento: que formas de intervenção? [The role of the private in planning: what forms of intervention?]. Revista Jurídica do Urbanismo e do Ambiente, 20, 43-79. [ Links ]

Putnam, L. L., & Wondolleck, J. M. (2003). Intractability: Definitions, Dimensions, and Distinctions. In R. Lewicki, B. Gray & M. Elliott (Eds.), Making sense of intractable environmental conflicts: frames and cases (pp. 35-63). Washington, DC: Island Press. [ Links ]

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. doi:10.1007/BF01405730. [ Links ]

RTPI - Royal Town Planning Institute. (2001). Existing Tools for Neighbourhood Planning. Retrieved from: http://www.rtpi.org.uk/media/7334/Existing-Tools-for-Neighbourhood-Planning.pdf [ Links ]

Schmidt, J. P. (2013). Mediation in Portugal: Growing Up in a Sheltered Home. In K. J. Hopt & F. Steffek (Eds.), Mediation: Principles and Regulation in Comparative Perspective (pp. 809-837). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Schüpphaus, M. (2007, November). Establishing neighbourhood dialogue – toolkit. Available at IMPEL - European Union Network for the Implementation and Enforcement of Environmental Law. Retrieved from: http://www.impel.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/2007-01-neighbourhood-dialogue-TOOLKIT.pdf [ Links ]

Sky, P. K. (2003, December). Land Tenure Disputes: Suitable for mediation? Paper presented at the 2nd FIG Regional Conference - Urban-Rural Interrelationship for Sustainable Environment, Marrakech, Morocco. Retrieved from: http://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/morocco/proceedings/TS10/TS10_2_sky.pdf

Susskind, L., & Weinstein, A. (1980). Towards a Theory of Environmental Dispute Resolution. Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review, 9(2), 311-357. Retrieved from: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/ealr/vol9/iss2/4 [ Links ]

Vasconcelos, L. (2007). Participatory Governance in Complex Projects. In G. Gunkel, & M. C. Sobral (Eds.), Reservoir and River Basin Management: Exchange of Experiences from Brazil, Portugal and Germany (pp. 114-124). Berlin: Technical University of Berlin. [ Links ]

Vasconcelos, L., Caser, U., Sá, R., Coelho, M., Silva, F., Ferreira, J. C... Bastos, M. (2011a). MARGov - Governância Colaborativa de Áreas Marinhas Protegidas & Cientistas Como Cidadãos E Cidadãos Como Cientistas: Relatório final - PARTE A [electronic version] Caparica: IMAR - Instituto do Mar/ DCEA/ FCT/ UNL. Retrieved from: http://www.wteamup.com [ Links ]

Vasconcelos, L., Caser, U., Sá, R., Coelho, M., Silva, F., Ferreira, J. C... Bastos, M. (2011b). MARGov - Governância Colaborativa de Áreas Marinhas Protegidas & Cientistas Como Cidadãos E Cidadãos Como Cientistas: Relatório final - PARTE B [Collaborative Governance of Marine Protected Areas & Scientists As Citizens and Citizens as Scientists: Final Report - PART B] [electronic version] Caparica: IMAR - Instituto do Mar/ DCEA/ FCT/ UNL. Retrieved from: http://www.wteamup.com [ Links ]

Vasconcelos, L., Caser, U., Pereira, M. J., Gonçalves, G., & Sá, R. (2012). MARGOV – building social sustainability. Journal of Coastal Conservation, 16(4), 523-530. [ Links ]

Vasconcelos, L., Pereira, M. J., Caser, U., Gonçalves, G., Silva, F., & Sá, R. (2013). MARGov –Setting the ground for the governance of Marine Protected Areas. Ocean & Coastal Management, 72, 46-53. [ Links ]

Wiegand, K. E. (2014). Mediation in Territorial, Maritime and River Disputes. International Negotiation, 19(2), 343-370. doi: 10.1163/15718069-12341281. [ Links ]

Recebido: Maio 2015. Aceite: Dezembro 2016.

NOTAS

iO PNPOT, approved by the Law No 58/2007, of 4th September, is a strategic instrument for spatial development, which sets out the most relevant options for national spatial planning. Furthermore, it constitutes the reference framework to be considered in the development of all other instruments for spatial planning, and is an instrument of cooperation with all other Member States, aiming at an European Union wide coordinated spatial planning. iiRegarding conflicts in territorial planning see, among others, Gualini (2015). iiiArticle 3(1)(g), Article 6(2)(a) and Article 49 of Law No 31/2014, of May 30th. ivArticle 6 of the Decree Law No 80/2015, of May 14th. vArticles 37, 50, 59, 67, 88 of the Decree Law No 80/2015, of May 14th. viActors/ Stakeholders means interested organisations and individuals (in this sense the designations actor, stakeholder are synonyms and do NOT refer to different theoretical concepts). viiIMPEL - European Union Network for the Implementation and Enforcement of Environmental Law. (s.d.). Solving environmental conflicts by dialogue. Available at: http://www.impel.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/brochure-dialoque-25-10-05.pdf viiiRegarding the Law No 29/2013 in Portugal, see Gouveia (2014) and Lopes & Patrão (2016). ixLaw No 31/2014, of May 30th and Decree-Law No 80/2015, of May 14th. xFurther information about the MARGov project available at http://www.maia-network.org/homepage/related_initiatives/projects_and_initiatives/22_991/margov_governancia_colaborative_de_areas_marinhas_protegidas xiSee International Mediation Institute (IMI): https://imimediation.org Center for Effective Dispute Resolution (CEDR): www.cedr.com/skills/mediation-training; Bundesverband Mediation (in Germany): http://www.bmev.de/aus-fortbildung/wie-werde-ich-mediatorin/standards.html