Introduction

In this article, the aim is to understand the legislators’ behaviour when deliberating on international agreements, with an empirical approach. Although the final decisions are taken on the floors of upper and/or lower chambers, here the committees are emphasised by understanding the preferences formation at this stage and how the committees can affect the final decision.1 The choice for analysing this step of the legislative process - and not the plenary - is to understand the political behaviour within the committees, contributing to the literature about committee systems (Curry, 2019; Giannetti et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2014; Sartori, 1975; Shepsle and Weingast, 1987), and precisely because they do not take the definitive decision regarding the bills, this is a level on which the parliamentarians’ behaviours might indicate clearly their preferences. Committees deserve attention as they are important loci of negotiation. Considering that committees are concentrated on specific themes (different from the plenary), they can incorporate discussions that do not happen in the same way on the floor. For this reason, even if the committees do not have the final say on the process, they can be decisive in preparing the final results. Moreover, the committees can be instrumentalised to speed up or slow down the overall process. Given the power assigned to them, they have the means to take less or more time to issue a report and deliberate for or against a bill. Assuming that legislators are divided in the government-opposition cleavage, they might want to block a president’s decision, jeopardising the government, or making the procedures faster and indicate a success for the government. This way, the motivation goes beyond the technical issues at the committee and fits the broader political scenario.

To begin to explore these issues, this paper follows a case study approach, a case aiming to be representative of the potentialities the legislators hold to act in international politics. We zoom in on the parliament of Brazil which has a bicameral structure (Chamber of Deputies and Federal Senate), and functions in a republican and presidential democracy. In addition to that, our case study analysis centres on a specific bill passed in the Brazilian national congress: the Protocol of Accession of Venezuela to the Southern Common Market ( Mercosur), signed in Brasilia on July 4, 2006. As a treaty approved at the regional level of the trade bloc, it was ratified by each Member State of Mercosur, until the final incorporation of Caracas in 2013. This bill is crucial not only because of the unusual time it took to be approved but also because it was extremely polarised, revealing the importance of bargaining and agency in parliament. The legislative consideration of this Protocol has been the object of several studies (Coelho, 2015; Feliú and Amorim, 2011; Insaurralde, 2014; Rocha, Domingues and Ribeiro, 2008; Santos, 2007; Santos and Vilarouca, 2007, 2011; Sloboda, 2015; Souza and Bahia, 2011), but the drivers of the parliamentary behaviour remain unknown. Furthermore, these studies concentrate their efforts on the final steps of the process, i. e., the plenary, overlooking what took place in the committees. Considering the polarisation seen in the discussion and approval in the committees, it becomes even more important to study them.

Additional studies are necessary to prove the drivers of the parliamentary votes, considering every stage in the legislative process, and this article contributes to a politicised episode that highlighted the political divisions among parliamentarians. That is to say, considering several factors that influence legislative behaviour, which determines voting for or against a specific bill. Focusing on legislative behaviour in the committee stage, the current article intends to foster the debate on this phenomenon, by answering the following research question: what determines the legislators’ votes, on regional integration agreements, during the committee stage?

Concerning Brazilian politics, the government-opposition cleavage is assumed as what best predicts voting behaviour in the committees. The partisan cleavages have been widely studied, including the nature of its coalitions (Abranches, 2018; Bottacchi, 2021; Figueiredo and Limongi, 2000; Ianoni, 2017; Limongi and Figueiredo, 1998). In the democratic period, the fragmentation of the party system led to a constant need for coalitions to govern. These coalitions can be unstable and have a broad ideological composition, which creates conflicts on specific agendas. It is important to remember that belonging to the government is situational once it changes every election.

Developing a twofold analysis allows us to interpret what determines the legislators’ votes, but also to include what elements are used in the debates to justify their position. That is to say, even if factors such as ideology do not seem to be determinant at the moment of voting, it is considered during the speeches to make their public statements. The empirical results of this study reveal the importance of this cleavage even when considering competing variables. The analysis indicated that belonging to the government or the opposition is the key explicative factor for determining the vote. Testing it against ideology, state origin and foreign trade with Venezuela was performed, but did not reduce the significance of belonging to the government.

Following this introduction, the next section covers the context of Mercosur enlargement and the domestic political scenario in Brazil. After that, a section is dedicated to explaining the theoretical framework. In the third part, we expose the methodology used in the current study. The fourth part presents the results from the Qualitative Comparative Analysis. In the other two sections, the processes in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate are detailed. Finally, the conclusion and the references are presented.

Theoretical framework

Situating this article under the double umbrella of International Relations and Political Science, the main focus is on legislative studies in the foreign policy field. Given that, this research unfolds within the interaction between the international and national levels and the determinants of legislators’ votes.

After the Cold War, an increasing number of actors have been playing roles in international affairs, as the parliaments gained agency in the international system, particularly through the so-called “parliamentary diplomacy” (Bajtay, 2015; Beetham, 2006; Malamud and Stavridis, 2011). One of the impacts of this international activity is a “Growing parliamentary input in foreign policy at the national decision-making level” (Stavridis, 2013, p. 9). Given that national parliaments’ behaviours at the domestic level are means to influence the outcome of foreign policy, they become relevant actors in the international sphere (Jancic, 2015). Needless to say, the legislative activity in foreign affairs can be seen in subnational, national, and international parliamentary bodies (Rocabert et al., 2019), but we focus here on the national parliaments, due to their role in treaty ratification.

Moreover, in the framework of contemporary liberal democracies, parliaments represent societal wishes and, for this reason, elected legislators increase the democratic legitimacy of the international process (Bajtay, 2015). In this sense, the Legislative branch can either cooperate with or confront the government in international affairs. Krasner (1978) points out that the Legislative branch, being composed of several actors, has fragmented interests that may diverge from the Executive position, which is more cohesive and centralised. More specifically, as the legislators are elected by subnational constituencies, they serve local demands, instead of the entire country. Because of this, there is a constant negotiation between the government and opposition parties in several steps, including the committees.

Although this represents a general pattern for legislatures, this does not hold true for every parliamentarian over time. In fact, each individual has a different behaviour when dealing with foreign affairs and some are more interested and active in the topic than others (Kinski, 2020; Marsh and Lantis, 2018). Moreover, some authors employ a cyclical approach to the legislative behaviour regarding foreign policy. According to them, there are moments in History that present issues that attract parliamentarians’ attention to international politics, increasing their activity (including the rejection of treaties), while in other periods they tend to agree with the Executive branch ( Henehan, 2000; Oliveira, 2003). In Brazil, in particular, there have been attempts to increase the legislative powers over foreign policy, indicating strategies to position the institution as a veto player in international politics - at least in the ratification of treaties (Anastasia, Mendonça and Almeida, 2012; Gabsch, 2010). All this represents the statement that international compromises depend on the willingness of two domestic powers: the Executive branch, which negotiates and signs; and the Legislative branch, which approves the entry into force (Putnam, 1988; Rezek, 2008).

Bearing in mind that Brazilian politics is highly partisan, along the government-opposition lines (Limongi and Figueiredo, 1998), one expects that this is translated into international agreements. In other words, given the cleavage existent when analysing domestic policies, we expect similar behaviour about foreign policy, following previous findings (Feliú and Onuki, 2014). Ribeiro and Pinheiro (2016, p. 484) affirm that “opposition members vote against the government to signal their general opposition, rather than their discontent with a particular proposal”. Considering that not every party is involved in international politics, following the domestic scenario can be their strategy (Mesquita, 2012). This is tested in the current article.

In this regard, the Legislative branch can be read as a veto player, which is an individual or collective actor whose agreement is necessary for the decision-making process (Mansfield, Milner and Pevehouse, 2007; Putnam, 1988; Tsebelis, 1997). Due to the nature of the parliaments, the veto players can be either institutional or partisan. This is seen in the fact that a bill passes through several phases in the legislative process, as a handful of committees in this case study and that the members of Congress may block the advancement of the procedures. One possible example of individual veto capabilities is agents who have agenda-setting powers within their institutions (Capano and Galanti, 2018). Martin et al. (2014) highlight the importance of committees in legislative work. As subunits of a parliament, they are entitled to limited authority, yet able to affect the passing of legislation (Müller, 2005). This is also an instrument of accountability over foreign policy, equalling it to other policies (Malamud and Stavridis, 2011; Pinheiro and Milani, 2012).

The detailed research, covering discussion and voting on each of the four committees, showed that not every representative has the same activity and interest in foreign policy and regionalism. Although the majority tend to vote according to the party position, some parliamentarians lead the others, providing arguments and taking the front in the debates, as entrepreneurs (Carter and Scott, 2004).

According to Merle (1978), political parties tend to prioritise domestic issues instead of foreign affairs. Thus, the international agenda is treated within the domestic political game, i.e., within the strategy elaborated to dispute power with other parties and to interact with the constituency. Due to the citizens’ concerns about the internal situation, the partisan logic is to operate in the sphere on which they can directly act, that is, in the nation-state. Therefore, foreign policy is used as an instrument of internal politics (Merle, 1976). Following this line, Cruz (2010) highlights that opposition parties might confront the government on foreign policy without major costs, as society is not usually chiefly interested in international affairs.

In the American continent, the predominant political system is presidential, with studies about the United States but also explaining Latin American realities (Alemán and Calvo, 2010; Figueiredo, Salles and Vieira, 2009; Jones, 2012; Mainwaring, 1990). Overall, it has been pointed out the existence of strong presidents, who have legislative success in initiating and approving bills. The mechanisms to achieve it are many, but agenda-setting powers and the composition of coalitions are some of them (Figueiredo, Salles and Vieira, 2009; Jones, 2012).

In Latin American fragmented party systems, and particularly in Brazil where cabinets usually encompass large coalitions, previous works agree that the government-opposition cleavage is one of the main determinants of the strategies that frame the parliamentarians’ behaviour (Clerici et al., 2016; Hix and Noury, 2016; Power and Zucco Jr., 2011). Nonetheless, some scholars recognise that members of Congress’ ideology and state of origin may trigger an alternative behaviour, in which they tend to vote against the party line (Bjereld and Demker, 2000; Hooghe, Marks and Wilson, 2002). Unpacking this, for some legislators, their ideology (in the left-right spectrum) or the subnational constituents they represent could motivate and define their votes, even if the party determines the opposite. This has a minor effect on the incentives for voting but helps to explain deviations from the pattern.

To sum up, the literature posits different motivations for the parliamentarians voting for or against foreign treaties, but one seems to be predominant in determining their decisions: belonging or not to the government. In view of the debate above, the following hypothesis is drawn: the government-opposition cleavage determines legislators’ behaviour. We test it by observing roll-call votes and including other control variables in the model to assess their significance. Furthermore, the usage of administrative procedures is analysed as a means to favour or hinder the approval of the Venezuela Accession Bill in the committees.

Methods

Regarding the research procedures, the study combines Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) with case study research methods to test the main hypothesis. We start exploring the conditions affecting roll-call votes in the committees, which is a standard way to explore legislative behaviour and to investigate party cohesion (Henehan, 2000; Yordanova and Mühlböck, 2015), and proceed to a more in-depth analysis of how discussions unfolded within the committees.

The QCA is an adequate method given the sample size and its ability to include qualitative and quantitative elements, seeking to draw solution formulas that present sufficient and necessary conditions for the outcome (de Block and Vis, 2019; Dusa, 2019). In other words, the result of the configurational analysis indicates which minimal scenario is essential for the occurrence of the outcome of interest. The QCA is a set-theoretic method, operating with Boolean logic to assess membership scores of cases in sets and to identify relations between phenomena as set relations (Schneider and Wagemann, 2012).

For this study, four conditions are used to assess the legislators’ voting behaviour on this bill. They are GOV (if the lawmaker is aligned with the government), IDEOL (if it is left-wing), REGION (if represents a state in Northern Brazil, close to the Venezuelan border), and TRADE (if represents a state with important trade ties with Venezuela). The outcome variable is whether the legislator voted for (1) or against (0) the bill. The unit of analysis is the votes of the parliamentarians in the committees, with a medium-N (106 observations). In Brasilia, this bill passed by two committees in the lower chamber (Committee on Foreign Relations and National Defence, CREDN, and Committee on the Constitution and Justice and Citizenship, CCJ) and two in the upper chamber (Brazilian Representation for the Mercosur Parliament, RBPM, and Committee on Foreign Relations and National Defence, CRE), with similar voting procedures, as all of them used the roll-call process. As seen in this article, there was variation in how the parliamentarians used administrative means to delay the deliberation.

In this fuzzy set, the outcome (VOTE) - represented by Y - is voting “Yes” in the session, i. e., for the incorporation of Caracas in Mercosur. An advantage of this dataset is that it is based on roll-call votes, allowing us to identify the behaviour of each parliamentarian, which would not be possible with symbolic voting. Here, we aggregate the two committees of the Chamber of Deputies and the two of the Senate, in order to understand what causes the legislative vote at the committee level, without differentiating by upper and lower chambers.

In addition to the QCA, a case study approach was adopted in specific parts of the investigation that need to be reconstructed, describing how the discussion evolved within the committees. Following Beach and Pedersen’s (2016) methodological guidelines, the aim of case-based research is not to purely describe the phenomena in a temporal sequence but to shed light on why specific social processes take place. The data used in this study comes from the official processing in Congress, summed to information about political preferences (to identify ideology and position regarding the government), as well as data regarding foreign trade. In sum, we use QCA to explain voting behaviour and proceed to a closer inspection of how the process evolved in the committees. This allows us to incorporate other explanations, such as the use of administrative procedures to speed up or slow down the deliberation.

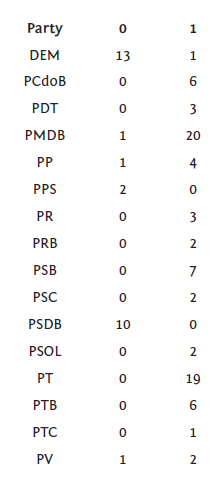

Moreover, the distribution of favourable (1) and contrary (0) votes is displayed in Table 1, with a total of 106. From this table, we can see the partisan cohesion, as there were parties unanimously voting for (PT, for example) or against (PSDB).22 On the other hand, parties such as PP and PV showed a division in their benches. There were 16 federal deputies at the CREDN and 61 at the CCJ (Chamber of Deputies), while in the Senate there were 12 parliamentarians at the RBPM and 17 at the CRE.

Considering these methodological notes, there is a section that develops the QCA, placing together the four committees into a single analysis, to detect common patterns among all the parliamentarians. The next section describes the context in which the case took place.

Venezuelan accession to Mercosur

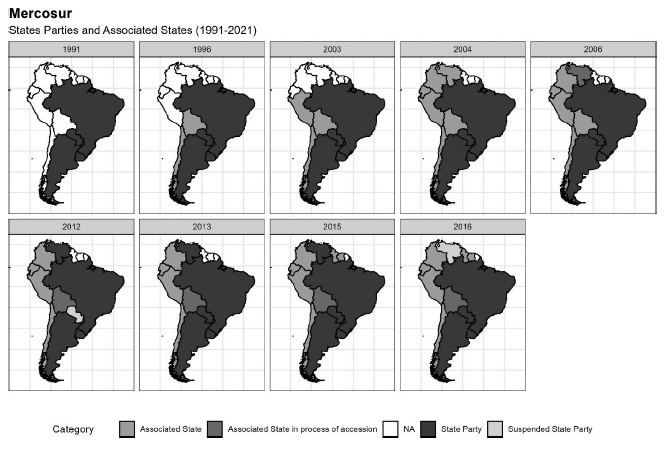

Mercosur was founded in March, 1991 by four members (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay). As shown in Figure 1, throughout its three decades of existence, all other South American countries were incorporated into the bloc, either as full members or as associated members. The majority is formed by the Associated States, which is a partial membership status to integrate the free trade area, but not the customs union. There are two states - Venezuela and Bolivia - that require full membership, i. e., to have all the rights and duties as the founding members. In parallel, there were efforts to deepen the bloc, by consolidating thematic agendas beyond trade (Doctor, 2013).

Venezuela started negotiating the accession in 2005, signing the Protocol - which is the judicial instrument that launches the formal process - in 2006. After the signature by the heads of government, it was referred to each national parliament to be approved. This step is necessary for an international treaty to enter into force. On the one hand, in the Argentinian, Uruguayan, and Venezuelan legislatures, it was rapidly approved (Díaz, 2014). On the other hand, Brazil and Paraguay took more time to ratify the Protocol, symbolising episodes on which the parliaments hampered an international decision. The ratification took seven years to be completed, precisely because the parliaments opposed the enlargement. The Venezuelan accession became a milestone in the history of Latin American integration for at least three reasons: the time taken for the decision; the polarisation around the issue and regarding Chávez’s government; and because it was the first accession to Mercosur, paving the way for further enlargement.

An additional aspect to understand why the approval of Venezuela took seven years is the suspension of Paraguay between 2012 and 2013 ( Marsteintredet, Llanos and Nolte, 2013; Recalde, 2013). In June 2012, amid a political crisis in Asunción, President Fernando Lugo was impeached, but the process in the national parliament was considered unconstitutional by the neighbouring states. Because of that, Mercosur decided to halt Paraguayan membership, which suspended its voting rights in the bloc. Therefore, it was no longer necessary to wait for Paraguay’s decision about the enlargement. This had a direct impact on the accession, as Venezuela was allowed to integrate Mercosur in 2012, without Asunción’s approval - Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay had already approved the enlargement (Sloboda, 2015). Despite that, in 2013, Paraguay ratified the Protocol, completing the legitimisation of the Venezuelan entrance. Focusing on the Brazilian ratification, the Protocol remained in Congress between 2007 and 2009 (Briceño Ruiz, 2009; Feliu and Amorim, 2011; Insaurralde, 2014). The total duration of the parliamentary deliberation was 33 months, with 19 of them spent in the committees’ phases.

During Chávez’s government, Venezuela increased its attention to Latin American partners, including the rapprochement to Mercosur (González Urrutia, 2006). Sustained by the oil international price and by the political changes in several governments, Venezuelan foreign policy placed regional integration as one of its main goals (Pedroso, 2018). For the other Latin American countries, the relationship with Caracas was the opportunity to partner with a country that was rich in resources and had a political willingness to strengthen the region against the liberal international order, which could equilibrate the distribution of power. Nonetheless, the Venezuelan accession had the “risk” to polarise Mercosur and incorporate a political agenda, i. e., it was a proposal to not limit the bloc to trade aspects (Benzi, 2014; Benzi and Zapata, 2013; Briceño Ruiz, 2006, 2010; Castillo, 2011; González Urrutia, 2006).

Previous research finds the relationship between the governments of Brazil and Venezuela, under Lula and Chávez, as a key aspect for the incorporation of Caracas and the motivation for the Brazilian government pushing this international measure (Arce and Silva, 2012; Gehre, 2010). It has been discussed if this was motivated by ideological proximity, geopolitical strategies, or economic interests, as the private sector saw a fostering in the international trade between the two countries, even before the accession (Magnoli, 2007; Rios and Maduro, 2007). Therefore, the Executive branch placed the enlargement as a foreign policy priority, which might have triggered the legislative reaction.

Given the above, this case was selected due to its relevance in presenting the parliamentary capabilities of employing formal administrative procedures to influence a political decision. The international agreement could not be ratified by the president until approved by the Legislative branch, which took almost 3 years. In other words, for 3 years, the opposition members of Congress had the opportunity to do an interbranch bargain, delaying what was considered a priority by the government and negotiating official positions as minister in the Federal Court of Accounts (Santos and Vilarouca, 2011). This can be defined as the agency held by legislators: controlling when a foreign policy will be approved. The importance of this episode is that most legislative decisions on foreign affairs are not polarised (Diniz and Ribeiro, 2008), and the Venezuelan case is an exception. Thus, it is important to note that assertive congressional behaviour is not common, as parliamentarians react only to a reduced number of treaties. Overall, the Legislative branch tends to abdicate its functions in international politics, but not permanently, as there are episodes that activate a posture to reclaim its veto power.

Conditions for voting in favour of Venezuela’s accession bill

In the current investigation, four conditions are studied to assess if they are necessary and sufficient for the outcome of interest: GOV, IDEOL, REGION, and TRADE. Condition GOV 1 corresponds to being a member of the pro-government coalition, while 0 includes the opposition. The data for deciding which parties were considered government came from their voting pattern in accordance, or not, with the ruling party (Estadão, 2017). The second, related to ideology, situates 1 as left-wing and 0 as right-wing, adapting the results of an expert survey (Tarouco and Madeira, 2015). Third, the legislators are divided according to the state and region they represent in Congress, being closer to 1 those who belong to geographically near regions to Venezuela, and those who are farther from the acceding member closer to 0. Finally, regarding trade, the legislators that received 1 are those who represent states that had Venezuela in the top 10 partners for exports and/or imports (Brasil, 2017). Searching the data for this period, we have classified the amount of trade (in dollars) to each country and disaggregated for each Brazilian state. Therefore, beyond the total values between Brazil and Venezuela, it is possible to see the relative importance of Venezuela to the 27 states.

Although correlations are not part of the QCA tradition, we have calculated them, as they bring to light findings that corroborate the results in this QCA section and enable us to test the assumptions through different techniques. First, there is a positive correlation between belonging to the government and voting for the accession (0.802), meaning that the legislators aligned to the Executive branch are more inclined to the outcome of interest. Moreover, between ideology and vote, the correlation is 0.599, that is to say, left-leaning parliamentarians tended to vote favourably for the inclusion of Venezuela. Concerning trade, the correlation was 0.005, which is an extremely low value, but indicates a trend that stronger economic relations led to votes for the inclusion of Venezuela.

Finally, and surprisingly, there was a low and negative correlation between vote and region (-0.079). Therefore, belonging to regions in Northern Brazil, geographically closer to Venezuela, decreased the chance of voting favourably for this bill. Despite the small significance of this value, this contradicts the expectation at the beginning of the research, which placed state origin as a possible factor to explain the favourable votes. As discussed below, this can be explained by the preponderance of GOV. Even if some parliamentarians aligned with the opposition voted for the enlargement, defending the economic and social relations with the neighbouring country (Mercosur would foster this relation and expand the regional integration process to this subregion of the continent), this was not true for all of them. The strongest ties with Venezuela are seen in Roraima, a state that is the main connection point between the two countries (Gomes Filho, 2011). Despite that, Roraima had only four parliamentarians in this sample, reducing its overall process.

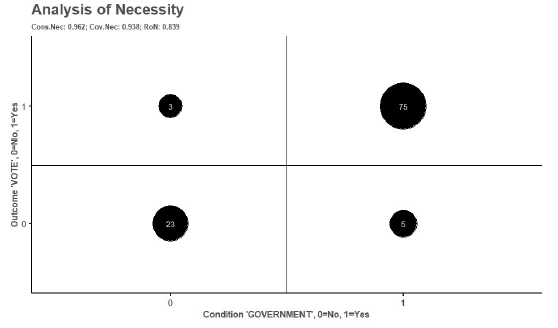

As seen in Figure 2, when running the analysis of necessity, only GOV meets the criteria.3 This indicates that when the outcome is present, GOV is also present. As shown below, this was the only condition present in the solution formula. Thus, the following XY plot also depicts the coverage of the formula for this analysis.

One can see that 70.76% of the N is covered by having both the condition and the outcome. The bottom left section is populated only by right-wing opposition representatives, belonging to DEM and PSDB. In the upper left quadrant, the three cases correspond to two parliamentarians of PSOL, the left-wing opposition, and one from DEM, representing Roraima, a state that has historical ties with Venezuela. Therefore, these deviances are explained by ideology and regional origin. They contradict what was expected in the hypothesis, opening room for marginal explanations that affect a minority of legislators, such as ideology and state origin.

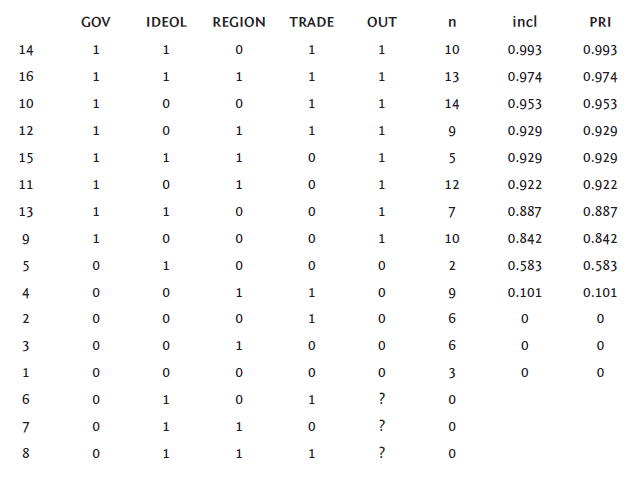

In Table 2, eight combinations of solutions were detected as paths to reach the outcome, while five do not lead to the outcome and three are logical remainders without empirical evidence - that is, possible combinations of conditions that had no observations to show what would be the result. Among all of them, we stress two rows. First, in line 16, we have 13 members of Congress that match all the expectations. They voted for the accession, were aligned with the government, were left-wing, represented a geographically closer region to Venezuela, and their states had good trade relationships with the acceding member. Furthermore, in row 9, ten legislators voted in favour of the protocol, while scoring 1 only in the GOV condition.

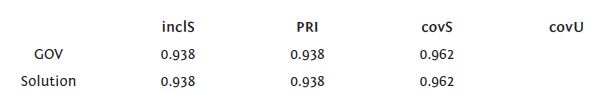

Given that, Table 3 shows the solution formula for the current analysis. When running conservative, intermediate, and most parsimonious solutions, all of them resulted in having GOV as the unique term, with good indicators of robustness.

The solution above confirms our hypothesis, bringing evidence that pro-government parliamentarians vote in favour of the accession. This is related to the fact that the accession was negotiated during Lula’s presidency and that the government placed it as a foreign policy priority to be approved in the parliament. Beyond voting for the enlargement of Mercosur, the legislators also voted for the government’s foreign policy regarding regional integration.

Having a single condition in the solution is representative of the heterogeneity seen in this sample. It was possible to analyse eight different scenarios, with variations in IDEOL, REGION and TRADE, reaching the outcome in all of them. Therefore, they do not seem to be sufficient to determine a favourable vote. Despite that, these findings do not rule out the importance of taking these conditions into account to complement GOV and explain the drivers of voting behaviour.

Because of that, the solution follows the theoretical expectations about the importance of the government-opposition cleavage. In addition to that, the absence of other conditions in the solution is a key finding of this research. Even if the role of ideology and state origin has been discussed, the analysis showed that they play a minor effect when considering the ensemble of parliamentarians.

In the next sections, we engage in an in-depth analysis of the processes in all four committees, in both the Chamber of Deputies and Senate. Observing the details of each phase, it is possible to understand how the government coalition articulated the approval of the bill, with the opposition parties trying to obstruct it. Moreover, the following section complements the QCA by indicating how elements such as trade, region and ideology are employed in the speeches, even if do not determine most of the votes.

Unveiling legislative behaviour within committees

After receiving the bill, the speaker of the Chamber of Deputies decides to which committees it should be sent, where it is analysed and voted on the merits. Following this step, it is voted in the plenary of the lower house. If approved, the speaker of the Senate forwards the bill to the deliberation of the committees in this house. Finally, the plenary of the Senate votes on it, and, in case of approval, it is sent for presidential ratification.

Figure 3 shows how much time passed between each stage, including the plenary sessions. The whole accession process took three years, but within the same legislative period (2007-2010), with the interbranch relations established after Lula’s and the parliamentarians’ re-election. Despite the political stability, economic performance and international projection, the presidency found the Senate more resistant to its projects in comparison to the Chamber. This is seen in the next pages, where we analyse the process in each committee.

Committee on foreign relations and national defence (chamber of deputies)

Although the Protocol was signed in 2006, President Lula referred it to Congress only in February 2007. Sending it one semester later indicates a strategic timing, because general elections were held at the end of 2006, re-electing the government, and composing a new Congress, with a different share of parliamentary groups. Therefore, if submitted right after the signature, the government would face an unknown scenario regarding the electoral results and how to bargain with new parliamentarians. Waiting until 2007 allowed the government to draw a strategy about how to pass the bill in Congress.

After being received by the Chamber of Deputies, it was referred to two committees. The bill was first passed by the Committee on Foreign Relations and National Defence (CREDN), and debated in two sessions in September and October 2007, with Doutor Rosinha (PT/PR) as rapporteur (Brasil, 2007b).

On October 24, 2007, the Protocol was approved by the committee ( Brasil, 2007a). In the beginning, the chair of the committee informed the parliament members of the committee in that session that he had received a handful of favourable opinions regarding the Venezuelan incorporation. Letters from chambers of commerce and industry, as well as from state governors arrived, representing 14 states in Northern and Northeast regions - which are geographically closer to Venezuela. They are evidence of support from the private sector and the state-level Executive branches, including from opposition parties such as PPS and PSDB. Thus, one can infer that the local businesspeople had an interest in strengthening the economic ties with Caracas, in order to increase the Mercosur benefits in the Northern part of South America.

It should be highlighted that in this first step, the deputies suggested other administrative procedures, such as public hearings, parliamentary missions to Venezuela, or inviting Venezuelan lawmakers to Brasilia, aiming to explain pending issues regarding Venezuela’s accession. Especially for the opposition, this meant an opportunity to hear diverging opinions and to seek more information to sustain their positions. Moreover, DEM and PSDB tried to postpone the debate or remove it from the agenda, extending the length of the legislative process. This strategy would allow to hinder it in the committee, preventing its ratification.

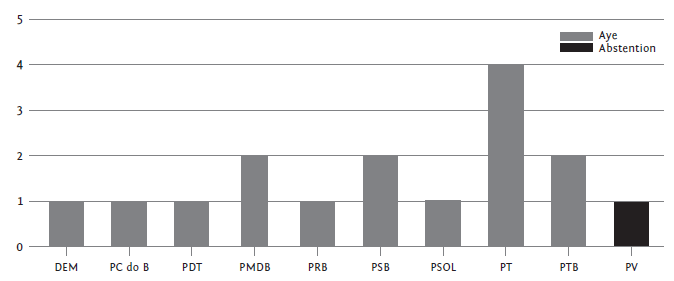

At the vote, the leaders of DEM and PSDB attempted to avoid the quorum of deliberation, to block the voting. Nonetheless, the tactics were unsuccessful, and the decision was largely pro-accession, with 15 votes for and 1 abstention, according to Figure 4. The disaggregated data shown for the four committees is the same as used above for the QCA.

Most of the voters were pro-government. However, two opposition deputies were in favour of the bill. Luciana Genro’s (PSOL/RS) vote can be explained based on her ideology, as PSOL is a socialist party, which supported Chávez’s government at that time. And Francisco Rodrigues (DEM/RR) represented a state that is historically linked to Venezuela, which might have been the cause for detaching himself from the party orientation.

Committee on the constitution and justice and citizenship (chamber of deputies)

Following the first committee, the Protocol was forwarded to the Committee on the Constitution and Justice and Citizenship (CCJC), where Paulo Maluf (PP/SP) was the rapporteur. His report (Brasil, 2007d) questioned the democratic conditions in Venezuela, as they could not fit the Mercosurian standards. Moreover, he stated that entering Mercosur could be an opportunity to improve international trade, going beyond oil. Finally, despite the criticisms, Maluf’s report sponsored the incorporation of the new member state, which is coherent with the fact that his party was in the pro-government coalition.

In this committee, the same voting behaviour was detected. With 44 favourable votes (72.13%) and 17 against (27.87%) on November 21, 2007, according to Figure 5. On this occasion, the benches of the DEM, PPS, and PSDB voted cohesively for the “No”.

Following these two approvals, the Protocol was submitted to the floor. Nonetheless, it had to wait almost one year to be voted on the floor, by the ensemble of federal deputies. There was a risk of rejection, which demanded new negotiations and explained the temporal gap between the processes in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate.

Brazilian representation for the Mercosur parliament (senate)

The bill was passed by the Brazilian Representation for the Mercosur Parliament (RBPM), a joint committee composed of both senators and federal deputies. At this stage, as in the first committee in the Chamber of Deputies, the bill also had the report from Doutor Rosinha (PT/PR) (Brasil, 2009). As noted in Figure 6, the deliberation by this committee took place on February 18, 2009, when it was approved by 7 votes (58.33%) and rejected by 5 (41.67%), which allowed its referral to the following committee.

Figure 6 Vote in the RBPM (Senate, 18 February 2009). Source: Own elaboration, based in Brasil (2008).

Despite having 18 incumbents, there were 12 parliamentarians present - 6 senators and 6 deputies - from 9 parties. It was found that DEM, PP, PPS, and PSDB voted against and PCdoB, PMDB, PRB, PTB, and PV in favour. Thus, the sample given by the Representation for the Mercosur Parliament allows us to deduce that the formation of preferences operates mainly under the government-opposition cleavage. Representing the composition of the Senate, 4 out of 5 votes against were given by senators, while the favourable votes were concentrated on the federal deputies.

Committee on foreign relations and national defence (senate)

Sent to the last committee (CRE), chaired by Eduardo Azeredo (PSDB/MG), the Protocol had Senator Tasso Jereissati (PSDB/CE) as rapporteur. Thus, there is a larger role of the opposition in important positions in the proceedings of the Senate, different from what occurred in the Chamber of Deputies. It is important to note that Brazilian senators are more used to international affairs because of some of their attributions (approving ambassadors to foreign countries, for instance). The opposition senators requested several public hearings to debate the issue, which has politicised the procedures. The guests had clear views and sides on the subject. Thus, they influenced the decision of senators but also brought external legitimacy to the decision of the Committee.

After four public hearings and three requests for information to the MRE, Tasso Jereissati (PSDB/CE) concluded his report, contrary to the approval of the Protocol of Accession. In this sense, the field of foreign relations appears as an area of interest to the parliamentarians to reaffirm their legislative powers and criticise the government.

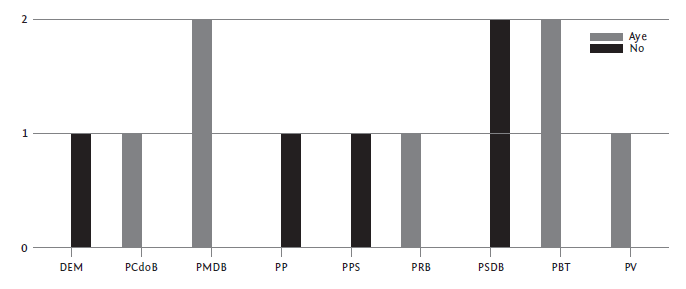

However, the opinion of the rapporteur Jereissati (PSDB/CE) was rejected, and, for its replacement, the separate vote of Senator Romero Jucá (PMDB/RR) was approved in favour of the Protocol. Thus, it was approved by 12 votes in favour (70.59%) and 5 against (29.41%). The appreciation on October 29, 2009, had a high degree of party loyalty and division between the minority bloc and the parties aligned with the government, as presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7 Vote in the CRE (Senate, 29 October 2009). Source: Own elaboration, based in Brasil (2008).

After concluding the processes in the senatorial committees, the bill was sent to the floor. In December 2009, it was approved with 56% of the votes, indicating a stronger opposition in the upper chamber (compared to the committees and the lower chamber). Nonetheless, after 3 years of negotiation, the government managed to have the approval, allowing the ratification of the enlargement.

Concluding remarks

Investigating the Protocol of Accession of Venezuela to Mercosur and how it was passed by the legislative committees in Brazil helped us answer the research question about what determines the legislators’ votes. Framing an international treaty, within the regional integration bloc, it was possible to assess the importance of government-opposition cleavage in their behaviour, while also considering other variables in the justification for the vote.

In view of the above, the empirical analysis sheds light on the government-opposition cleavage as the main determinant for legislators voting in the committees, confirming our hypothesis. In this specific case, ideology, region, and trade were not the main determinants to approve the enlargement. Thus, they are marginal explanations for specific legislators. However, additional studies should be conducted, and discourse analysis could be an option to understand the relationship between what is said and what is put into practice.

To sum up, the committees play a significant role in the process of treaty ratification, as they are instances on which both government and opposition can debate and bargain on the paths the bills will take. Before going to the floor, the legislators can employ several procedures to hinder or speed up the processes, assessing which is the interest of the parts and how it integrates the government strategy.

The findings from this study, emphasising the committees’ phase, contribute to other studies by understanding how the committees can affect the final result. Even if it is approved, the timeline may be stretched due to the debates with the opposition. Furthermore, this article assists in knowing the role of government, ideology, region, and trade in determining the voting or the content of the discussions. In addition to that, the use of administrative procedures to influence the process can also be studied in other cases.

Bearing this in mind, future areas of research can be expanded from this article. To better understand the importance of parliaments in international relations, it is worth studying other polarising treaties that are deliberated by national legislatures. Undoubtedly, this could be done by looking at the Brazilian parliament (with the ongoing Protocol of Accession of Bolivia to Mercosur, as an example), but also at other similar political systems. Within Latin American reality, further research could be done to compare the parliamentary behaviour in the parliaments of Mercosur members. If all of them need to be analysed, it is important to know if the reception of Mercosurian legislation is the same in all the parliaments or if there is variation.