Introduction

By 10th may 2023, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has infected 765 million people worldwide and accounted for 6.9 million deaths.1Since survival of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome has dramatically improved, morbidity and sequelae in survivors have now become major subjects of interest.2-4While most fully recover, it is increasingly recognised that some patients will suffer from prolonged illness with studies reporting symptoms persistence in 50% two years after diagnosis.2 The associated disability impacts not only the elderly and individuals with underlying conditions but also the young healthy population, with corresponding social and economic burdens.5,6

The health care pressure associated with the COVID-19 pandemic forced hospitals worldwide to treat critically ill patients outside intensive care units, frequently in suboptimal conditions and with less individualized care.7 Data regarding outcomes in critically ill survivors treated in non-intensive care units (ICU) settings is missing.

Impact of an illness usually goes beyond objective physical outcomes and encompass subjective measures like mental, emotional and social functioning.8,9The societal implications of the pandemic, such as quarantine and social distancing,10 and cultural background11,12may also have influence on patients’ recovery and long-term outcomes. The evaluation of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), as a self-perceived physical and mental status, is increasingly recognized as a pivotal outcome complementing traditional parameters, such as mortality.13 Its assessment may help healthcare providers to identify the associated factors with unfavourable outcomes and recognize the aspects of disease management that needs to be enhanced in new programs and interventions for improving the outcomes.14It is known that COVID-19 may lead to poorer HRQoL both in short and long term.2-4Data on the Portuguese population outcomes is scares,15,16and is missing in critically ill survivors who were treated in non-ICU settings. This longitudinal cohort study aimed to describe 3 and 6 months HRQoL outcomes in a Portuguese cohort of critically ill SARS-CoV-2 patients trea-ted in an advanced respiratory care unit (ARCU).

Methods

This prospective unicentric study was conducted in two phases and included all critically ill SARS CoV-2 survivors admitted to a dedicated respiratory unit from November 2020 to November 2021. The inclusion criteria were patients aged over 18 years-old, with COVID-19 diagnosis by PCR on pharyngeal swab and admission to the ARCU for noninvasive respiratory support (NRS). One hundred and forty-nine eligible patients were recruited, at discharge, to an outpatient evaluation at 3 (T3) and 6 (T6) months. Patients with cognitive impairment (ICD 10: F01-F99, G80, Q00-Q07, Q90-Q99), unable to complete the questionnaires or that refused to participate were excluded at T3.

PHASE 1. HOSPITALIZATION

A general ward was converted in an ARCU dedicated to critically ill COVID-19 patients, due to limited ICU beds. This 14-bed unit was integrated in an Internal Medicine infirmary with 26 beds. All 14 beds allowed continuous monitoring by telemetry with electrocardiogram trace, peripheral oxygen saturation and respiratory rate. The unit had a nurse-patient ratio of 1:5 during day shifts and 1:6 in night shifts. Four Internal Medicine doctors provided medical assistance during daytime. During night shifts patients’ assistance was guaranteed by the Internal Medicine doctors from the emergency department and ICU team. All patients were admitted for treatment with NRS techniques such as high flow nasal cannula (HFNC), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and noninvasive ventilation (NIV). Patients in need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), vasopressor sup-port or renal replacement therapy were transferred to ICU. After NRS techniques weaning, patients were transferred to other non-ARCU beds in the same infirmary or equivalent Internal Medicine general wards. All patients had access to rehabilitation in the ARCU and maintained treatment during all hospitalization if transferred to other infirmaries.

Information regarding demographics, clinical evaluation, NRS techniques, length of stay and therapeutic ceiling concerning candidacy to IMV were collected during hospitalization.

PHASE 2. OUTPATIENT VISIT

Outpatient evaluations were made at T3 and T6. In each evaluation patients were asked to answer QoL, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaires and to preform tests to evaluate objective indicators.

QUALITY OF LIFE QUESTIONNAIRES

To assess subjective recovery, participants were asked to grade their symptoms and limitations answering to St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)17 and EuroQoL 5-Dimension 3-Level (EQ-5D-3L) questionnaire.18,19 Both questionnaires were validated for the Portuguese population and were applied by a physician.

EQ-5D-3L is a general HRQoL composed by 5 life dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) with 3 levels of perceived problems (level 1: no problem; level 2: moderate problems; level 3: extreme problems). The EuroQoL visual analogic scale (EQ-VAS) records the patient’s self-rated health on a vertical visual analogue scale where the endpoints are labelled ‘Best imaginable health state’ (100) and ‘Worst imaginable health state’ (0). EQ-5D-3L is one of the most frequently applied questionnaires to COVID-19 survivors, allowing comparisons.

SGRQ is a pulmonary-specific HRQoL questionnaire. It has been used is several respiratory conditions including interstitial and infectious lung diseases.20,21It is a highly complex and detailed questionnaire, allowing a more pro-found knowledge on HRQoL. It is composed by 3 items (symptoms, activity and impacts) and each component score is derived by dividing the summed weights, unique for all questions, by the maximum possible weight. The score range for each domain and total score from 0 (no impairment/no effect on HRQoL) to 100 (maximum impairment/ perceived distress). Normal values for adult healthy population range from 8-12 points. SGRQ allows for longitudinal follow-up as a mean score change of 4 units is associated with slightly, 8 units with moderately and 12 units with very clinically relevant changes. SGRQ was validated for Portuguese by Sousa and collaborators (2000) and translated by Taveira and Ferreira (SPP, 2006) (data not published).

PSYCHIATRIC QUESTIONNAIRES

A battery of standardized instruments evaluating anxiety (GAD-7),22 depression (PHQ-9)23and post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD (PCL-V)24 was administered at both visits. Provisional diagnosis of anxiety, depression and PTSD was made if GAD-7≥10, PHQ-9≥10 and PCL-V≥31, respectively.

OBJECTIVE MEASURES

Blood gas analysis and 6-minute walk test (6MWT) were executed by a trained physician at both visits. Heart rate, oxygen saturation and the Modified Borg Dyspnoea Scale were monitored throughout the test. Patients with conditions limiting 6MWT performance, such as musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, or neurological conditions, were exempted.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

No statistical sample size assessment was performed a priori, and sample size was the number of patients treated during the study period in the ARCU. Continuous variables are described using mean and standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Categorical variables are reported as frequency and percentages. The normality was checked using Kolmogorov-Smirnov or Shapiro-Wilk tests, as appropriate.

The answers to the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire were dicho-tomized into no problem (level 1) and some or extreme problems/disability (levels 2 and 3). Patients’ outcomes were compared at T3 and T6 using Paired Student’s t-tests or Wilcoxon for continuous variables or McNemar test for categorical variables. Independent variables were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, for categorical data; or Student’s t-tests or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, as appropriate. Patients with normal SGRQ (≤12 points) or with minimal clinically significant improvement (reduction of ≥4 points) (group 1) were compared to patients with stable (but >12 points) or worse SGRQ (group 2). The association between no improvement in SGRQ at T6 and demographics/data from de hospitalization was calculated using a univariate logistic regression model and data is presented in odds ratio and 95% confidence interval. Variables with p values less than 0.1 on univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariable analysis using foward stepwise logistical regression.

Missing data on 6MWT was 36.7% and only patients with data on T3 and T6 were analysed.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 27; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and a p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the ethics committee of Centro Hospitalar Tâmega e Sousa (Portugal). Data from hospitalization were prospectively recorded after ethical approval (phase 1). For this purpose, informed consent was waived by the institution due to the heath care burden felt at the time. At the ambulatory evaluation all patients participated voluntarily and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants at T3 (phase 2). All procedures were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Results

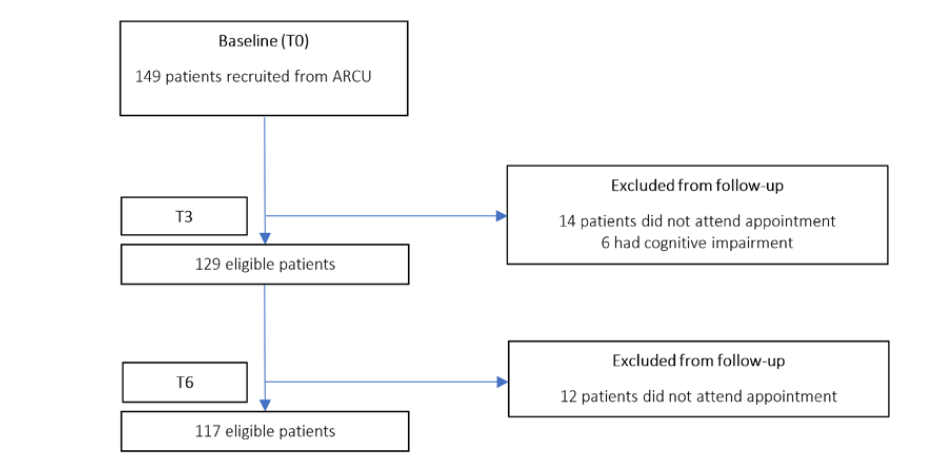

One-hundred and forty-nine patients were recruited from the ARCU (Fig. 1). Among them, 135 attended T3 evaluation. Four patients were excluded due to dementia and 2 due to Down syndrome at T3. One-hundred and seventeen patients were enrolled. No patient refused to participate or withdraw informed consent during the study period.

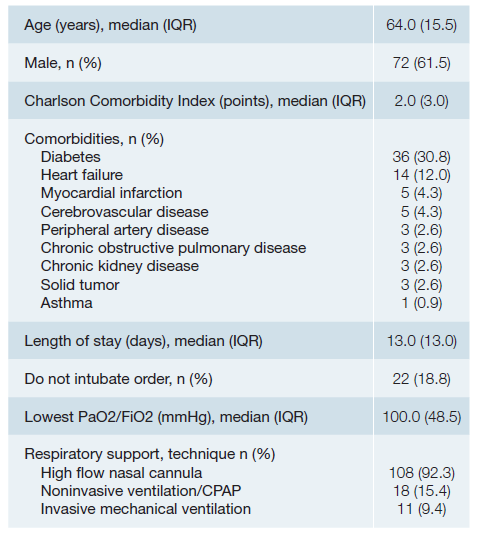

Study sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 64±15.5 years, and the majority were men (61.5%). Forty-five percent had at least one comorbidity included in Charlson comorbidity index. The most frequent was diabetes, followed by heart failure. The median hospital length of stay was 13 ± 13 days. More than 90% of patients were treated with HFNC. Eleven patients were transferred to ICU for IMV.

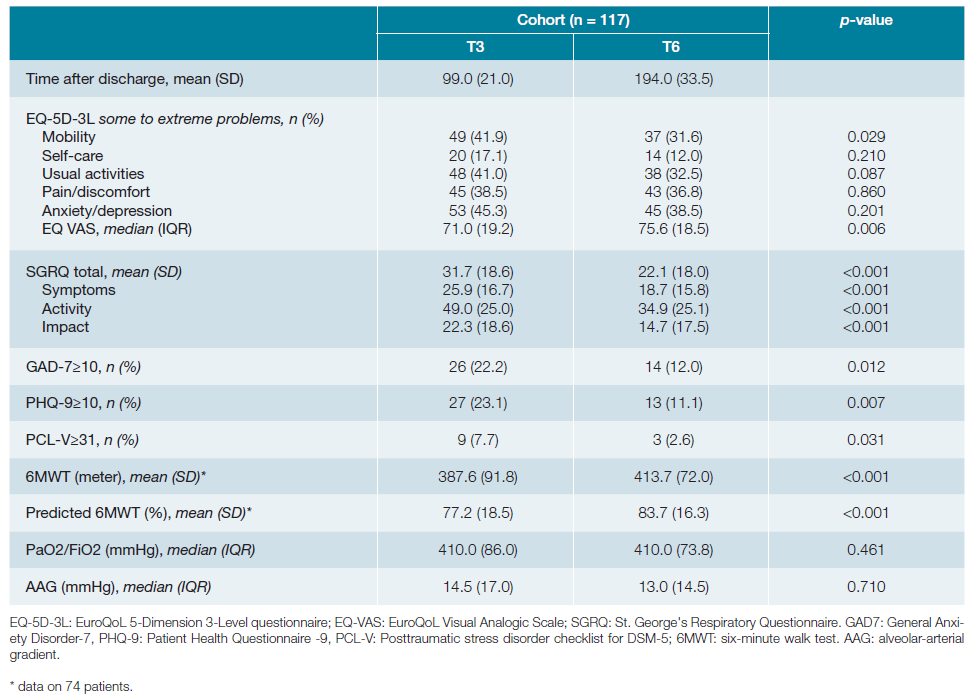

Outcomes evolution over time are detailed in Table 2. Improvement was observed in total and all SGRQ specific domains, but only in mobility and EQ VAS scale in EQ-5L-3D questionnaire. Forty-four out of 117 patients had EQ VAS scale ≤ 70%. Prevalence of psychiatric problems such as anxiety, depression and PTSD decreased significantly over time. Seventy-four patients (63.2%) preformed 6MWT at both visits.

The remaining were not assessed due to musculoskeletal limitation (26 patients), symptomatic ischemic heart disease (1 patient), 3rd degree atrioventricular block diagnosed at T6 (1 patient), symptomatic intracardiac shunt (1 patient), refusal to participate (14 patients) at T6. A significant improvement in 6MWT performance was observed between timepoints. Characteristics and outcomes according to SGRQ results at T3 and T6 are detailed in Table 3.

At T3 and T6, patients felt their current health status to be very good in 6.0% vs 12.9% (p = 0.005), good in 41.0% vs 43.1% (p = 0.003), moderate in 46.2% vs 37.9% (p <0.001), bad in 5.1% vs 6.0% (p <0.001) and very bad in 1.7% vs 0.0%, respectively. Comparing T3 and T6, 41.1% vs 58.1% of patients considered that their chest condition did not limit any activity they would like to do (p <0.001), 36.8% vs 27.4% stated that their respiratory condition was limiting 1 or 2 activities (p <0.001), and 22.3% vs 14.5% complained that were not able to do most or everything of the things they would like to do (p <0.001). Globally, 6.8% and 5.1%, after 6 months, considered that their chest condition was causing quite a lot of problems or was the most important problem they had, respectively.

In terms of sick-leave patterns, at T3, 62.4% of patients confirmed no impact of respiratory symptoms on their work, 25.6% reported that symptoms interfered or made them change work, and 12.0% stopped work. At T6, 71.8% had no complains but 4.3% were still not working.

Six months after discharge 4.3% of patients reported feeling embarrassed in public due to their cough or breathing; 2.6% considered their chest distress was a nuisance to family, friends or neighbours; 13.7% got afraid or panicked when they were not able to control their breathing; 5.1% felt a lack of control regarding their chest problem; 9.4% did not expect to get any better; and 18.8% felt that they had become frail or invalid due to the respiratory condition associated with COVID-19 infection.

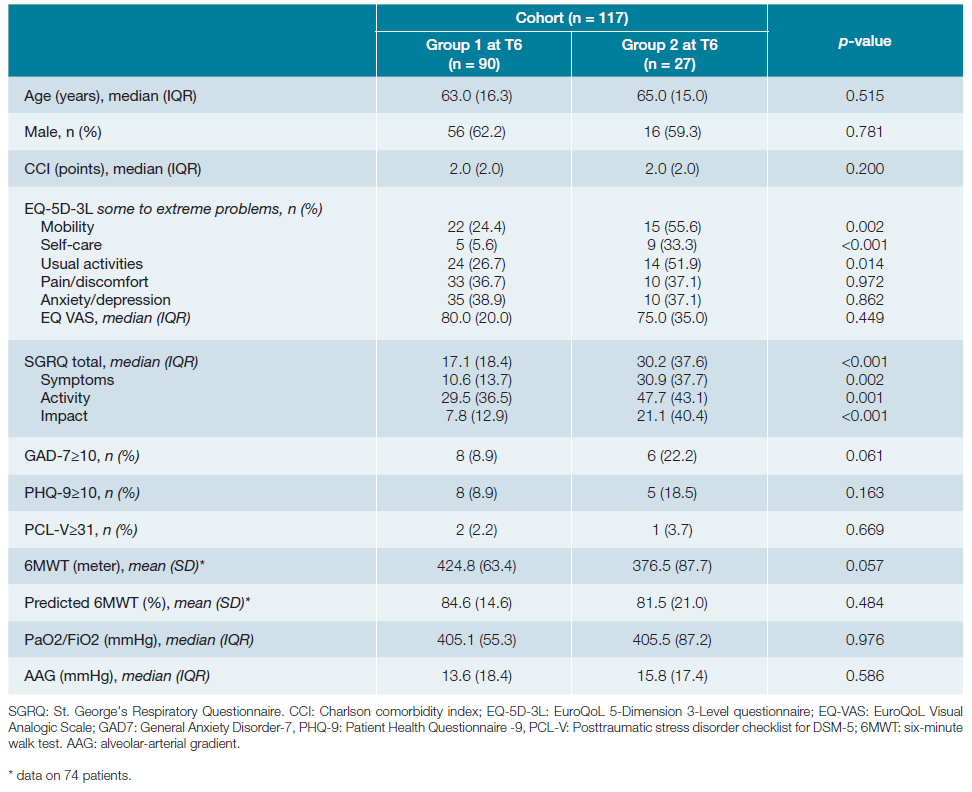

At T6, SGRQ was normal in 18.8% of patients, significantly improved in 58.2% (slightly in 15.4%, moderately in 10.3% and highly in 32.5%), stable in 14.5% and worse in 8.5%. Table 4 presents outcomes according to SGRQ improvement status at T6.

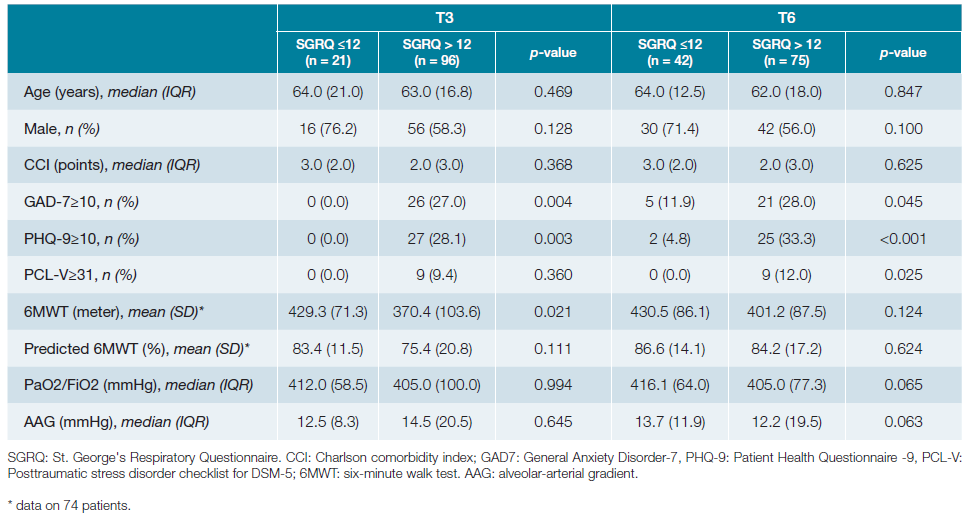

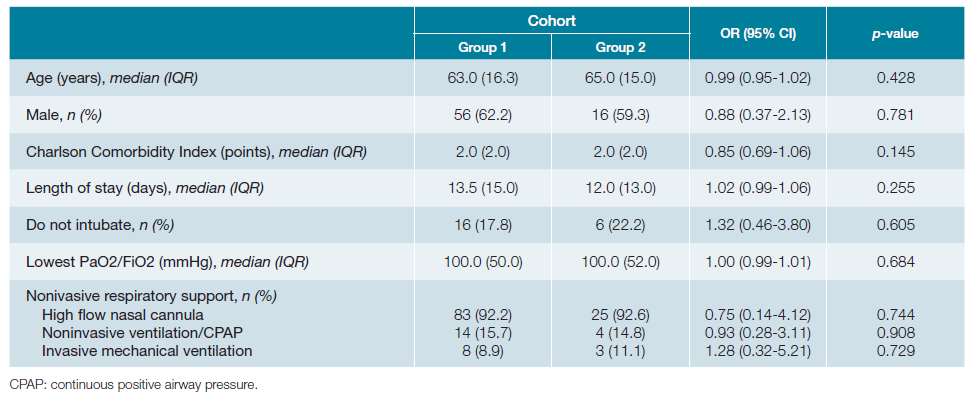

Associated factors with no improvement at T6 were analysed comparing groups 1 and 2 (Table 5). Association between outcomes and age, gender, do not intubate order, severity of acute respiratory distress syndrome and NIRS technique was not found.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first mid-term study on HRQoL in a Portuguese population of critically ill SARS-CoV-2 survivors treated in an ARCU. We report a significant improvement over-time in EQ-5D-3D mobility domain, EQ VAS and in all SGRQ domains. Our results are consistent with other studies on SARS-CoV-2 patients.2,16

After 6 months, almost 80% of participants had normal or significant improvement in SGRQ, more than 50% considered their current health status to be good or very good and only 6% judged their condition to be bad. Nevertheless, even after 6 months and despite the improvement, patients reported difficulties in 12%-39% of EQ-5D-3L domains, comparable to other reports.2,3Findings from the validation study of EQ-5D-3L version for the Portuguese population described problems in self-care (4.8% vs 12.8%), mobility (16.8% vs 37%), usual activities (16.3% vs 37.4%), pain/discomfort (44.7% vs 60.2%) and anxiety/depression (34.4% vs 56.0%), in patients without (sample 1) and with comorbidities (sample 3), respectively.18 The mean EQ VAS was 75% in healthy individuals and 59% in those with comorbidities. Considering that our cohort has almost 50% of patients with comorbidities and our patients age is similar to sample 3, our results seem to approach the expected for Portuguese population. The exception are pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression domains for which our results are better. One study on COVID-19 reported an EQ VAS inferior to 70% in more than 50% of participants, a higher value when compared to ours.4 A relevant issue to take into consideration is the impact of social and cultural backgrounds on perception of health status. An interesting study comparing mental health, QoL and optimism between Portuguese and Brazilian individuals described higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and optimism for the Brazilian individuals and higher levels of QoL and pessimism for the Portuguese population.11 The authors stated that, although both countries have a similar language and cultural roots, Brazil is a low to middle-income and low educated country with significant social and economic inequalities in where the pandemic was interpreted as a threat to the economy rather a public health problem in the political scenario. These findings stressed that, despite the higher percentages of apparent disability, a significant proportion may not be a consequence of COVID-19 infection and results must be interpreted with caution.

We used a respiratory-specific instrument to determine HRQoL after hospital discharge following treatment of COVID-19-related pneumonia with severe respiratory failure. SGRQ has been used as a tool in this context.25-27 Erber et al25 reported symptoms scores of 19.3 and impact scores of 16.7, after 6 months, similar to our data. In our cohort, mean total SGRQ scores were 10 points higher than the expected for a healthy Spanish population aged between 50 and 70 years-old.28

We observed a favourable evolution of 6MWT between time-points, confirming objective improvement as documented in other studies.29 While 6MWT and blood gas analysis were not significantly impaired after 6 months and given the fact that continuous improvement was noted, altered lung function may not explain, by itself, the losses in HRQoL. Data suggest that Portugal is the second European country with the highest rate of psychiatric disorders, mainly because of its high proportion of anxiety (16.5%) and depressive disorders (11.5%).30 To measure the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on general population, Aguiar et al31 evaluated anxiety and depres-sion symptoms in a Portuguese sample. Anxiety and depression were observed in 26.9% and 7.0%, respectively. It is known that SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with psychiatric morbidity with studies reporting high prevalence of anxiety, depression and PTSD months after diagnosis.32 Impairment on the anxiety/depression EQ-5D-3D domain, in a Portuguese sample of SARS-CoV-2 survivors, was the most frequently reported, peaking at six months after discharge (39.3%).16 We found significant improvement in the prevalence of provisional diagnosis of anxiety, depression, and PTSD over time. While our results for anxiety/depression EQ-5D-3D domain are similar to the reported by Gaspar et al,16 after applying specific questionnaires, we notice lower rates of anxiety, depression and PTSD after 6 months, than the reported both in Portugal and abroad.32,33To our knowledge, there’s only a Portuguese study on critically ill SARS-CoV-2 survivors using specific questionnaires for mental diseases.33 The authors used GAD-7 and PHQ-9 and assessed patients by telephone post-discharge. Symptoms of depression and anxiety were found in 29% and 23%, respectively, after 6 months.33 As about 75% of patients were treated with IMV and 21% with ECMO, it is difficult to compare with our findings. Interestingly, comparing patients according SGRQ, those with abnormal results 3 months after discharge had significantly higher rates of anxiety and depression. After 6 months a significantly higher prevalence of PTSD was also noted. Age, gender, comorbidities, and objective measures didn’t seem to influence HRQoL results. Mental health impact of disasters outlasts the physical impact, suggesting today’s elevated mental health needs will continue well beyond the coronavirus outbreak itself.

Robust mental health policies are needed in Portugal to reduce stress-related symptoms and to promote cognitive resilience and mental health in daily life, and critically in challenging times.

As sick leave can be seen as an indicator of health in a working age population, Westerlind et al evaluated a Swedish cohort, in whom more than 60% of participants were on sick leave at least for a month and 9% were still not working 4 mon-ths after diagnosis.34 Other reports show variable sick leave rates, ranging between 12% and 54% after 6 months.35,36Work problems are reported to be higher in long COVID groups, with 52% of work time missed due to absenteeism and 60% due to presenteeism 6 months after diagnosis.29 In our study, after 3 months, 12% of our patients were still not working, a value that decreased to 4% after 6 months. These results are significantly lower than expected, showing that despite the clinical severity of the acute illness, functional recovery was the norm. Of note, we did not evaluate economic fragilities in our cohort, which can be a confounder as lower income wage earners could have returned sooner to work due to financial struggling, despite persistent symptoms.

Despite the overall good results, almost 20% of patients felt to be at least frailer than previously and 5%-7% of patients reported significant problems associated with their chest condition, some of them considering it was the most important problem they had. Interestingly, 14.5% of the population did not improve and 8.5% worsened on SGRQ evaluation between the 3rd and 6th month after discharge. Published data suggests that female gender, older age, physical symptoms after discharge, comorbidities, ICU admission, prolonged ICU stay, and being mechanically ventilated were the most frequently reported factors associated with low HRQoL.37,38We did not find association between poor outcomes and several demographic and therapeutical variables.

This study has some limitations. First, this is a small, convenience sample recruited from a single centre in Portugal. It is uncertain whether our findings can be generalized to the Por-tuguese population, and larger studies are needed to confirm this data. Second, the variant-specific SARS-CoV-2 infection seems to be associated with different long-term outcomes.39 We do not have data on this topic, however, as the Omicron variant was first reported to WHO on 24 November 2021, the majority of our cases probably were caused by previous variants. Third, we do not have information about HRQoL and mental health questionnaires from our cohort previous to COVID-19 infection, limiting the attribution of symptoms to the infection, nor a control group from ICU. Fourth, the data used in this study came from patients’ self-reported questionnaires. In the future, clinical diagnoses of mental and psychiatric disorders should be used.

Conclusion

Despite the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the management outside ICU, our population seem to cope well with significant improvement over time and lower rates of work absenteeism. However, a small proportion of individuals still complain about HRQL problems 6 months after the infection, reinforcing the need of strong health policy with investment in both rehabilitation and mental health.

Previews Presentations

28º Congresso Nacional Medicina Interna