Introduction

Congenital granular cell tumor (CGCT) is an uncommon benign lesion that affects fetuses and neonates. It shows a predilection for females, and the anterior alveolar mucosa of the maxilla is the most affected intraoral site.1,2 As for its histogenesis, hypotheses include odontogenic, neural, histiocytic, pericytic, fibroblastic, muscular, and even undifferentiated mesenchymal cells. However, the CGCT’s histogenesis remains unknown, and there is no consensus in the literature.1,3,4

Clinically, CGCT presents as a single circumscribed growth with sessile or pedunculated implantation, color ranging from pink to reddish, and size ranging from a few millimeters to about 10 centimeters in diameter.2 Multiple lesions involving the maxilla and mandible have also been described in 10% of cases.4,5-7 Histopathological images reveal rounded voluminous cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and slightly basophilic oval nuclei. CGCT’s microscopic appearance is very similar to granular cell tumors, and the differential diagnosis between the two is based on etiological, clinical, and immunohistochemical aspects.1,3,6,8

Surgical excision is recommended immediately upon detection of the lesion, and spontaneous regression is rare. Large lesions can cause feeding difficulties and airway obstruction in the neonate.5,6,9 This study reports a case of CGCT and discusses clinical and histopathological characteristics, as well as differential diagnoses from other lesions, while emphasizing a multidisciplinary approach.

Case report

A 10-day-old Black female newborn was presented at a Stomatology Service with a nodular lesion in the oral cavity. Intraoral physical examination revealed a pedunculated exophytic nodular lesion of firm consistency and coloring similar to the mucosa, located in the anterior region of the left upper alveolar ridge and measuring approximately 3.0 x 2.0 cm in diameter (Figure 1). This mass was causing breastfeeding problems but no airway obstruction. The infant’s mother did not mention any adverse perinatal event, and the lesion was detected only at birth.

Figure 1 Clinical aspect. Pedunculated nodular lesion on the anterior upper alveolar ridge of a newborn.

Considering a diagnostic hypothesis of congenital epulis, pediatric and anesthetic evaluations were performed to plan the surgical excision of the lesion, which occurred under general anesthesia with orotracheal intubation, as usually recommended in such cases.1,3,10 The lesion was completely excised using electrocautery, bleeding was minimal, and the infant recovered with no complications, achieving normal breastfeeding.

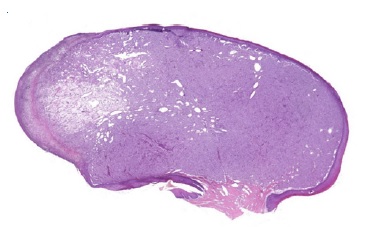

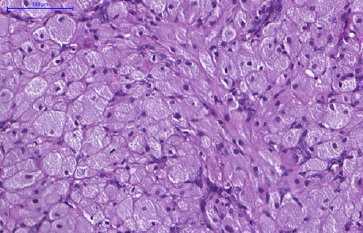

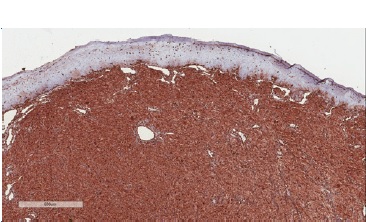

Histopathological examination revealed a benign, well-circumscribed lesion characterized by a proliferation of polygonal cells amid a sparse stroma (Figure 2). The cells exhibited rounded morphology and abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm.

Figure 2 Histopathological features of CGCT. Well-circumscribed lesion characterized by the proliferation of polygonal cells amid a sparse stroma (H&E; 40x magnification).

Some of the rounded-to-oval-shaped basophilic nuclei appeared as expelled toward the cell’s periphery. The dense fibrous connective tissue stroma was sparse, with a mild infiltrate of mononuclear inflammatory cells and blood vessels.

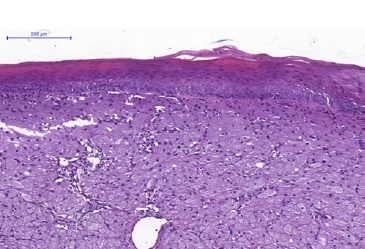

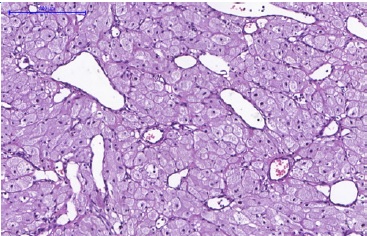

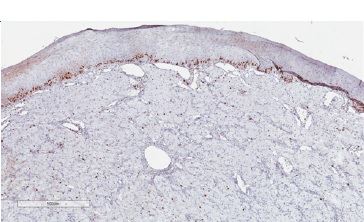

The epithelium lining exhibited atrophy of its epithelial ridges at its greatest extent, with an area of focal ulceration (Figures 3, 4, and 5). In order to better characterize the lesion under study, immunohistochemical staining for vimentin (Figure 6), Ki-67 (Figure 7), and S100 (Figure 8) was performed.

Figure 3 Histopathological features of CGCT. The lesion is lined by a parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium exhibiting atrophy. There are lesion cells in the lamina propria (H&E; 100x magnification).

Figure 4 Histopathological features of CGCT. Blood vessels of varied shapes and sizes amid the granular cells (H&E; 400x magnification).

Figure 5 Histopathological features of CGCT. In detail, the cells show a rounded morphology and an abundant and eosinophilic cytoplasm with granules. The basophilic nuclei, with a rounded-to-oval shape, are positioned at the cell periphery (H&E; 400x magnification).

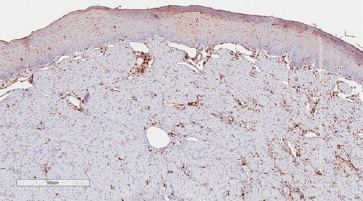

Figure 6 Immunohistochemical features of CGCT. Diffuse immunoexpression for vimentin (400x magnification).

Figure 7 Immunohistochemical features of CGCT. Low proliferative index through analysis of Ki-67 immunoexpression (400x magnification).

Figure 8 Immunohistochemical features of CGCT Granular cells exhibit immune-negativity for S100 (400x magnification).

The clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical aspects led to a diagnosis of CGCT. The patient has been under follow-up for 3 years, with no clinical signs of recurrence. The child’s parents signed a free informed consent form explaining and authorizing data usage for academic reasons. The institution’s Research Ethics Committee approved this study.

Discussion and conclusions

CGCT was originally described by Neumann, who called it “congenital epulide.”11 Since then, few cases have been reported in the literature. In the last 5 years, only 22 studies2,7,10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30 reporting CGCT occurrence were published (Table 1). The Greek-derived term “epulid” means “swollen gums” and is nonspecifically used in dentistry for hyperplastic lesions in the gingival tissue. The use of more specific terminology to name CGCT has been suggested, including “congenital granular cell lesion,” “newborn gingival granular cell tumor,” “newborn congenital epulis,” “congenital granular cell myoblastoma,” and “granular cell fibroblastoma.” However, due to the occurrence of extra-gingival cases, the term “congenital granular cell tumor” is likely most appropriate.9,31

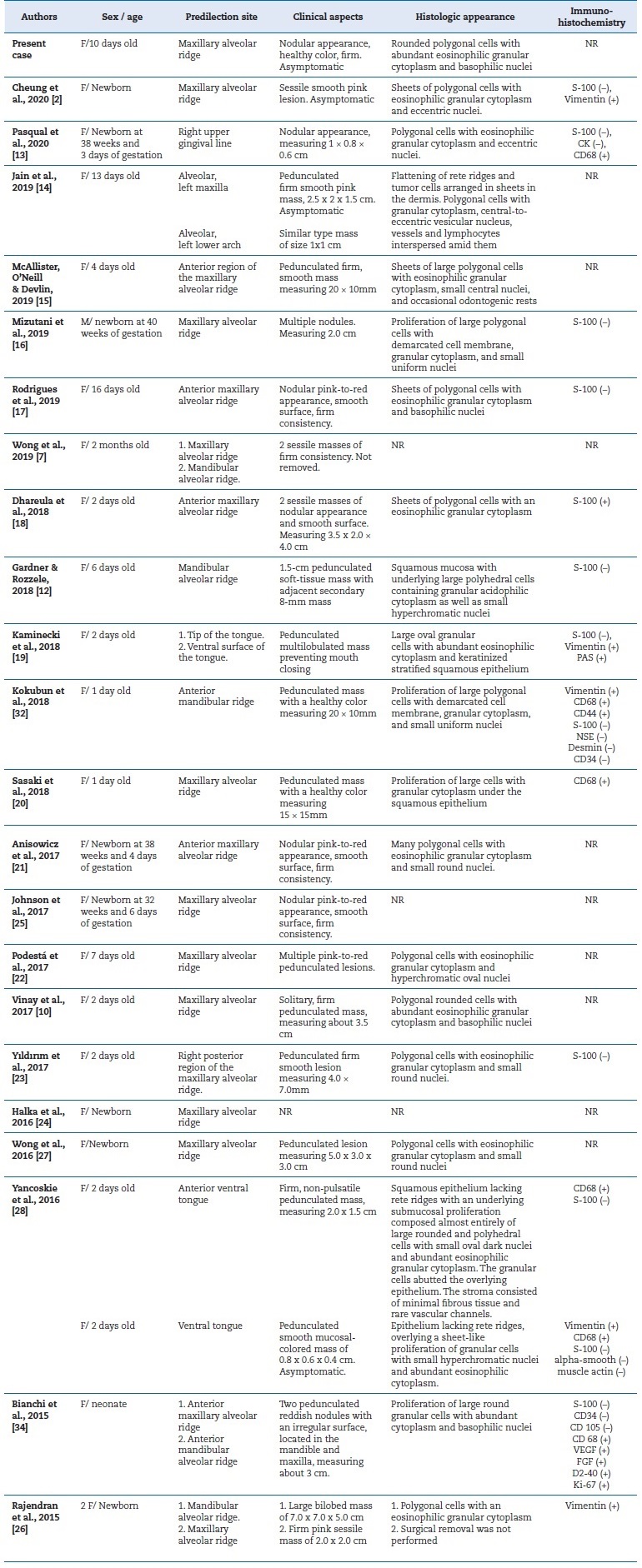

Table 1 Summary of clinical cases reported in the literature in the last 5 years.

F - female; M - male; SMA - smooth-muscle actin; CK - cytokeratin; NSE - neuron-specific enolase; NR - not reported

CGCT is most frequently located in the anterior maxillary alveolar ridge and has demonstrated a marked predilection for female neonates compared to males at a ratio of 8:1. Clinically, CGCT presents as solitary lesions that are rarely multiple, are similar in color to the mucosa (or reddish), of firm consistency, with a smooth and non-ulcerated surface, and with sessile or pedunculated implantation. Typically, the CGCT is 1 to 2 cm in diameter, despite some reports of lesions larger than 9 cm.1-3,5,31The present case report has clinical characteristics consistent with the findings shown in the literature.

Although its histogenesis is not well established, some authors believe that CGCT is a reactive entity.1,3Others believe that this lesion’s cellular phenotype is related to pericytic or myopericytic cells due to the marked vascularization typically observed in its stroma, with increased pericytic proliferation around small venules.5 Furthermore, due to its intrauterine origin and female predominance, the development of CGCT has been suggested as closely associated with maternal hormones.1,3,31 Despite a possible endogenous hormone influence, this hypothesis becomes untenable when considering the absence of estrogen or progesterone receptors in the lesion cells. Thus, the reason for the female gender preference is still uncertain.5,8,32

Due to CGCT’s rarity, healthcare professionals sometimes cannot clinically recognize it, leading to misdiagnoses. It is thus extremely important to perform an adequate anamnesis that, together with microscopic aspects, can facilitate diagnosis. Upon histopathological examination, CGCT is very similar to granular cell tumors: both lesions exhibit tumor growth composed of polygonal eosinophilic cells containing cytoplasmic granules.5,33 However, while CGCT demonstrates atrophy of the epithelium lining, the granular cell tumor has a characteristic pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in its epithelial lining. Although both lesions have a predilection for females, their location differs: CGCT exclusively affects the alveolar ridge of newborns, while granular cell tumors can affect many sites in the body, despite being more common in the tongue, and are most common between the third and sixth decades of life.1,3

In differential diagnosis, other lesions that present granular cells should be considered, such as granular cell melanoma, certain fibro-histiocytic neoplasms, smooth muscle tumors, and soft-tissue alveolar sarcoma. Immunohistochemical techniques can be used as a complementary tool to characterize the lesion better and discard other histologically similar lesions. Previous studies have evaluated the immunoexpression of proteins such as S100, smooth muscle actin (SMA), desmin, calponin, neuro-specific enolase (NSE), CD68, vimentin, cytokeratins (CKs), CD34, CD31, and Ki-67.5 In the present study, we observed lesion cells’ immunopositivity for vimentin, negativity for S100, and a low cell proliferation index in Ki-67 analysis. These findings reinforced CGCT’s non-neoplastic nature and suggested a mesenchymal origin.

CGCT immunohistochemical profile analysis increases diagnostic accuracy and enables clinical management and treatment. In contrast to granular cell tumors, which present granular cells immunoreactive for vimentin and S100, CGCT’s lesion cells present strong and diffuse immunostaining for vimentin, negativity for S100, and weak, focal immunostaining for Ki-67.1-3,29 Immunoreactivity for S100 and NSE in the granular cell tumor suggests a Schwann-cell origin. On the other hand, CGCT is usually negative for S100 and positive for vimentin, suggesting a mesenchymal origin. However, CGCT positivity for NSE has been reported, indicating a possible neural origin.1,2

Although uncommon, spontaneous remission is possible because CGCT’s growth tends to cease after birth, as in cases of small lesions that do not interfere with breathing or feeding.34 Yet, most studies recommend surgical excision of the lesion under local or general anesthesia.1,3,10 There are no reports of recurrence after surgical CGCT excision, even when there are tissue remnants of the lesion.1,3 In addition to surgical excision, techniques using electrocautery and carbon dioxide laser, or even gingivoperiosteoplasty, can be used for subsequent primary alveolar reconstruction, promoting proper alignment and normal dental development.30

The present study reviews CGCT’s histopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics, comparing them with data reported in the literature and emphasizing the differential diagnosis from other oral lesions. Due to CGCT’s rarity, studies that analyze its clinicopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics can provide greater knowledge, enabling better diagnosis and clinical management.