Introduction

Heritage is selection, choice, and as such, it involves disputes and clashes. Here, a specific dimension of heritage - that is, prison heritage - is addressed, examining the collections protected by unconventional safeguard institutions like memorials in prisons, cumbersome, and latent inheritances. Prisons and their vestiges safeguarded as memory spaces. They represent immediate and significant issues for the present, marked by controversies that make their positive affirmation as a heritage complex (Macdonald, 2009).

This article undertakes an analysis of the collections of the Paulista Penitentiary Museum (Museu Penitenciário Paulista), in São Paulo, Brazil, and the Museum Centre of the Directorate-General of Reintegration and Prison Services (Núcleo Museológico da Direção Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais), in Lisbon, Portugal.1 The objective is to problematize the collections of paintings and drawings held by these two spaces, pieces whose creators are either totally unknown or about which we have only partial information.

The relationships established by and arising from these objects, and their potentialities to discuss the notion of prison heritage, will be analyzed. Such questions are delimited within the arenas of present time history, an unfinished history filled with new meanings, bringing out the unwanted, the uncomfortable. Also discussed will be the trajectory of the research that led to the identification of a previously unknown painter, José Joaquim de Almeida, artistic name Pinho, looking at the texture, the paths, and the meanings contained in the uses of his works, which enable prison heritage to be examined from these categories.

The Prison Heritage

Prison archives, and their museum counterparts, hold objects that are interesting and contradictory in nature: from the knives used in rebellions and ropes once employed in escape attempts or suicides to the presentation of scenarios that strive to reproduce the prison environment, its cells, and its places of punishment. The intention to have the visitor feel like the imprisoned person is reduced to a fun experience, a one-off, free of any type of reflection, and disassociated from the daily lives of those who seek out such spaces out of curiosity or for enjoyment.

Some of these venues seek to combine the experience of the exotic with their desire to encourage reflection on the part of the visitor, an arduous task that does not always attract the public2 in large numbers, with rare exceptions. As Michael Welch (2015) has rightly pointed out, after visiting ten prison museums on six different continents, such places generally present a simplistic narrative that merely describes the evolution of penal systems by recreating environments and displaying old uniforms (often also recreated and worn by mannequins), as well as photographs and documents. These places of prison memory show that society beyond the walls relates to prison in an ambiguous and contradictory way, as will be demonstrated throughout the present text.

The patrimonialization of medieval dungeons and fortresses linked to castles and/or historical buildings is common and almost unquestionable3 due to their long-standing history as attractions and lack of direct connection with the present. They are spaces converted into testaments to by-gone eras that have few features in common with the present. Patrimonialization tells about how we deal with not only this distant past, but also the recent and uncomfortable past. Prisons are not memory, they are functioning, they continue in the present, and they are usually only remembered when they threaten society beyond the prison walls. What enables memory are the connections with the present, which allow for reflection on the current implications of prison spaces.

Factors such as the criminalization of poverty, which in an elastic and brutal web now encompass the survival strategies of the poorest groups, as along with the fight against drug trafficking, are the main elements that help explain the boom in incarceration rates in almost every country in the Western world (Salla, 2006). In this difficult scenario, the mass media, which report rebellions and irregularities in the penitentiary system in a reductionist and sensationalist way, end up contributing to the already historically and socially consolidated construction of the negative social representation of the prison and the prisoners. This view does not account for the complexity of the prison problem, and it reduces any possibility of reflection and understanding of the prison as a space imbricated by historical and heritage values.

Certainly, Brazil, which has the third-largest prison population in the world,4 known nationally and internationally for violence and bloody rebellions in prisons, has particularities that reverberate in the tessitura of what is meant by prison heritage. Since the 1960s, the destruction of deactivated prisons and penitentiary buildings is shown with great repercussions, and media coverage has been recurrent (Santos, 2013). Such erasures serve to silence certain troublesome memories,5 and in this removal of prison buildings from the urban fabric, the safeguarding of collections is made difficult or is prevented outright due to the absence of clear heritage policies regarding this very specific typology of heritage (Borges and Santos, 2019).

Since the 1980s, the number of prisoners in Portugal has exceeded prison capacity, with the total number of detainees much higher when compared to the rest of Europe.6 Many buildings have been adapted and converted into prisons although facilities were erected following the 1867 prison and penal reform, spaces designed to be model prisons, such as the Lisbon and Coimbra penitentiaries (Adriano, 2010). The maintenance of these monumental buildings, which still continue to perform the same original functions in the two cases cited, and their preservation as heritage of public interest, has generated numerous clashes as a broad range of intentions and needs come into conflict: the duty of memory, the demand for preservation, the desire for demolition, the desire for erasure, the question of new uses and the re-adaptations necessary for everyday life.

In the case of prisons, therefore, and their original function of incarceration, there exists a strong and imponderable mark linked to the difficulties involved in preserving a marginal heritage: little or nothing is identified, and almost always uncomfortable issues arise.7 The difficulty thus lies in thinking about the historical and heritage meanings of what touches upon the controversial issues of our own time, such as prisons of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many of which are still in operation, such as the Lisbon Penitentiary, which has been fulfilling its primary function of incarceration since its inauguration in 1885, and the São Paulo Penitentiary, inaugurated in 1920 but now housing the Sant’Ana Women’s Penitentiary.8 Both are patrimonialized spaces and the target of continuing discord on the question of their maintenance.

In Brazil and Portugal, the reflection on this controversial heritage, when it exists, is almost always restricted to the academic field and to interested heritage and architecture professionals (Adriano, 2010; Martins, 2011; Santos, 2013; Borges, 2018a, 2018b; Borges and Santos, 2019; Borges and Sepúlveda, 2020). In other countries, such as France, the attempt to draw the attention of society in general to the fragility of this heritage typology has relied on the public mobilization of historians. In 2014, the newspaper Libération published two articles that presented the theme as an agenda, pointing out its importance and alerting to the destruction of prison heritage.9 The discussions were driven by historians, and they constituted a manifesto entitled “Prisons are also part of our heritage” (author’s translation), inviting the authorities and the general public to reflect on the memory linked to these places and their remains. Signatories to the manifesto included names such as Philippe Artières, Michelle Perrot, and Jean-Claude Vimont. The idea was to establish public debate on the subject and to raise social awareness, but society remained indifferent and the proposal did not produce the desired reverberations. Prisons are not to be remembered.

The clashes surrounding prison heritage put the historians in direct confrontation with events on the battlefront (Mauad, 2007), coexisting with his objects and witnesses and being part of the story he wants to tell. The patrimonialization work that apprehends prison places requires a process of “patrimonial qualification” (Fleury and Walter, 2011: 24), which makes them loaded with conflicting meanings, as they bring a topic that society wants to forget to the fore, causing the unwanted to emerge. They do not bear witness to a bygone age, but offer a testament to our own time. There is a challenge to be faced, then, as the cultural heritage category has infiltrated the public debate as a social demand, implying “past public policies”, turning the recent past into a problem to be faced, confronted, solved, overcome (Rousso, 2016: 29).

As mentioned, the notion of “prison heritage” has been discussed in France in the last decade, driven by frequent demolitions of prison buildings (Borges, 2018b). Historian Jean-Claude Vimont, who died in 2015, then a professor at the University of Rouen (France), sought to outline the initial parameters to build a concept with yet undefined contours. Beyond the often monumental and imposing buildings, the discussion revolves around the collections and expressions by and about human beings in different situations of being deprived of freedom: prisoners of political repression, ordinary prisoners, abandoned minors and/or youth in conflict with the law, etc. (Vimont, 2014).

Along with the broadening concept of cultural heritage comes the need to segment it to better understand its specificities. I understand that this new category should be constructed based on its dissonances and contradictions, as well as the inconveniences it raises, perceived as elements that potentiate and institute their meanings.

From the 1990s, it is possible to recognize a process of patrimonialization of prison spaces concerned with considering a greater aesthetic and narrative diversity, loaded with complex issues. Many prison places have been transmuted into museums, memorials, visitation centers, and historical and national parks. In some cases, the concern is to report dead and missing victims of fascist and dictatorial regimes, constituting an important part of the assets in question, although they do not always occupy prison facilities. As for post-war Holocaust archives, museums, and memorials linked to the victims of military dictatorships in Latin America, they are memory spaces that seek to fulfill a memory duty marked by political, social, and ethical issues (Borges and Santos, 2019).

The memory linked to ordinary prisoners and young people in conflict with the law, however, would be the reverse of this process, following the winding paths I have tried to trace, establishing little or no articulation between the preservation of buildings (not always possible or desired) and memory aspects and the more sensitive and personal dimension of the confinement experience. Among the most recent concerns are the potentialities of accessing insurgent records: various objects and traces linked to daily institutional life, such as the prisoners’ graffiti or murals, works of art, weapons and utensils, letters, and codes invented to enable intramural communication, etc.

It should be noted that many of the prison-linked memory spaces are difficult to map.10 Informal memorials and museums created within the prison spaces are significant, and almost always proposed by officials whose intention is to store documents, photographs and antique objects considered of historical value by the institution. Both in Brazil and Portugal, it is possible to observe initiatives that show a concern to preserve collections linked to the history of prisons, to systematize and gather documents and objects scattered by different institutions to safeguard them. The creation of spaces for safeguarding, when created by institutional initiatives, are shown in a hybrid field between the archive and the museum, housing varied collections, lacking identification and research, such as the penitentiary museums. Others are not always open to the public or have limited and controlled access, as they often operate within the prison space itself, and they are subject to its rules of operation and security, such as the Archive and Museum Centre of the Directorate-General of Reintegration and Prison Services in Lisbon.

Weaknesses, Erasures, Silences, and Absences

In July 2014, the opening of the Paulista Penitentiary Museum was reported by the Brazilian press, highlighting its collection:

The collection shows something of the creativity of prisoners who participated in workshops in prisons. The paintings are remarkable for their detail and creativity. Several are from the 1930s, and they needed to be restored. The collection also has makeshift microwaves with a lamp and aluminum foil, detailed furniture, and even a miniature motorcycle. All built behind bars since 1920. [...] The illicit creations of prisoners in cells are also among the 21,000 pieces in the museum’s collection. In the collection there are weapons fashioned from various types of materials. The makeshift tattoos devices too. There is even a contraption to make cachaça with leftover food. The visitor can also see the dark cells, discontinued in the 1970s, which served as a kind of punishment for some prisoners.11

Faced with this profusion of traces, I intend to concentrate on the paintings, drawings and mural inscriptions that, along with the knives, the ropes and the makeshift still,12 are often seen as showing a certain cunning and ingenuity that would emerge in some of those who go through the prison experience. In some cases, these objects are called upon to say more, corroborating the institutional discourse that wants to show that the prison can have its positivity, its space of creation and resocialization, so desired and so difficult. They are objects endowed with agency and marked by contradictions that serve an institutional knowledge/power that wants to determine what must be preserved and the uses given to prison memory.

The path taken by these objects is varied: from daily searches meant to seize prohibited objects to the collection of evidence of infractions committed in prison. Taken from different places, the objects occupy different positions and meanings: evidence of illicit acts, exemplary traces of a possible regeneration, spontaneous graffiti or inscriptions, understood or not as prison art or heritage, biographical records of the confinement experience, etc.; meanings that no longer speak of the object itself, but the relationships that shape its social existence (Brulon, 2015).

Thanks to Michel Foucault (2002 [1975]), we now talk about a new rationality of punishment, from the pain of torment to the space configured within the institutional walls. An architectural project structured as an instrument of punishment, anchored in the internal logic of determining the spaces for confined bodies. This internal logic has enabled a vast production of records aimed at systematizing information and diagnostics that allow us to understand the practices adopted to conduct daily life. Amid the official documents, insurgent sources can be found, traces of the deviant, condemned to leave no trace, whether woven by the institution in its attempt to control and train the bodies. Traces motivated by the institution, inserted in the institutional practices.

From the individual processes (or medical records) to the works produced in the workshops or spontaneously during or after confinement, it is possible to find traces that show the reappropriations and the prison experience from the eyes of those directly involved. Such traces sometimes appear as insurgencies, which bring counter-meanings that made it possible to register an unauthorized gift. The paintings, in their various supports and motivations, can, in some cases, be read as insurgent sources.13

Most of these records are lost due to the destruction of buildings and/or the lack of care when dealing with the protection of collections. Others suffer when the support allows for the object to be moved, but when it reaches the museum and prison archives, often attached to the official documentation, there is insufficient background work to allow for their proper identification.

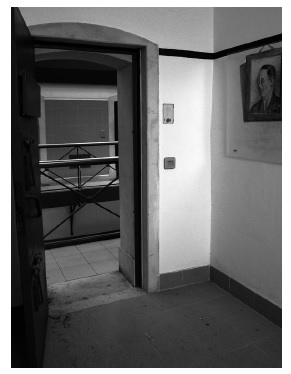

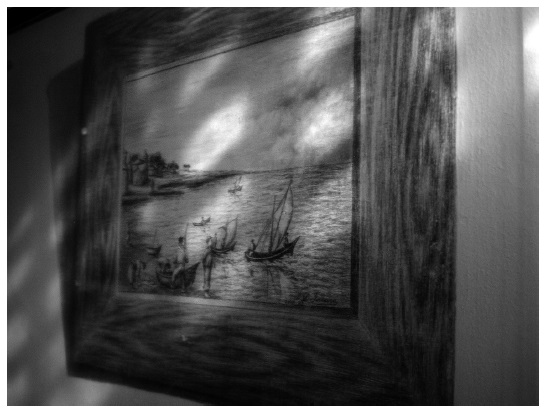

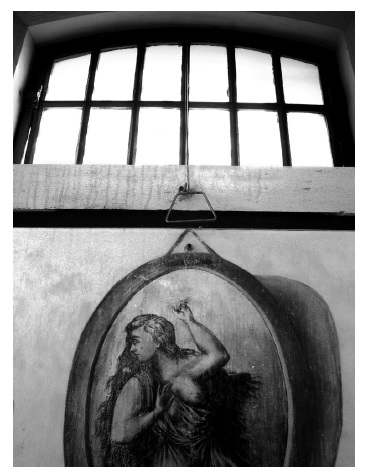

Among the most emblematic and difficult to preserve situations are the drawings and murals on various supports (cell walls, bathrooms, courtyards, etc.), which leave marks in the prison space (Aquino, 2017) and which are intertwined with the architecture of the location. In this sense, an emblematic case occurs in the Coimbra Penitentiary. The painted cell, as the institution’s staff names it, stands out for the drawings on the walls, which mimic framed paintings. The authorship is unknown, the work of a prisoner who, according to officials, was said to be an inmate in the second half of the twentieth century (see Images 1, 2 and 3).

The cell is not in use, remaining closed, protected from any current prison functions. Few know of its existence. The images in question were taken by photographer Pedro Medeiros, and included in the exhibition Intro - Coimbra Penitentiary on the 120-year history of the institution, which produced a book with images and texts. In the publication (Medeiros, 2009), authors from different areas such as architecture and law establish the building’s heritage value, based primarily on its monumentality. The painted cell is not mentioned in the texts, it is as if it did not exist, but the photographs are witness to its existence and its strength as a vestige of life in prison. Who is the author? What is his motivation? Nothing is known.

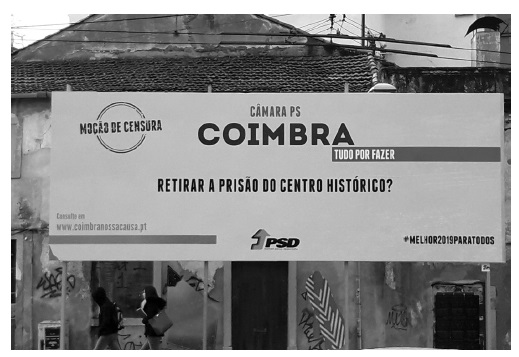

The process of classification of the property, which makes it a monument of public interest,14 makes no mention of the painted cell, meaning it might potentially not be included in any efforts to preserve graffiti or murals in the face of new proposals for use of the prison space, constantly rethought and poorly defined.15 In early 2019, a billboard placed in front of the Penitentiary by the Social Democratic Party (while the City Council was governed by the Socialist Party) brought up the question: “Remove the prison from the historic city center?” (see Image 4).

Credits: Viviane Borges, Coimbra, 2019.

Image 4 Billboard “Remove the Prison from the Historic City Center?”

In the case of Coimbra, the question suggests what would be “best for everyone”, yet it removes the historicity of the prison space, making its presence in the historical center a problem to be overcome. The Penitentiary would not be history, but annoying. Both the preservation of the buildings and the collections that inhabit them are fragile possibilities in view of the desire to erase prison memory.

The fragility of graffiti and wall inscriptions has led to the search for virtual records. In France, the Criminocorpus website created the first digital museum dedicated to penitentiary heritage and the history of justice, proposing the use of original tools such as virtual prison visits, virtual exhibitions, etc. (Renneville et al., 2018). Faced with the impossibility of safeguarding material, there is a call for photographic campaigns, exhibitions, removal or collection of relics, and even cell reconstitution in other prison spaces (Soppelsa, 2010a, 2010b). The fragile and desperate solution that clings to any kind of record against the threat of disappearance.

In addition to the weakness in the absence of preservation policies, the lack of information about the authorship of the works present in the prisons is widespread. Among the paintings and drawings at the Paulista Penitentiary Museum16 and the Archive and Museum Center of the Directorate-General of Reintegration and Prison Services17 in Lisbon, it is possible to find traces of individuals who in different times and spaces left important records for posterity. They are repositories of a variety of documentation on prisons, including spaces for abandoned minors and/or youth in conflict with the law. The collection of objects and documents encompasses sculptures, sacred art, furniture, safes, paintings, drawings, uniforms, weapons, handcuffs, photography and film instruments, seized illicit objects, models, musical instruments, instruments of anthropometric measurements, etc. In addition to reports, individual processes (medical records), photographs, and other documents.

In a land full of absences, the lack of patrimonial policies regarding this type of collection corroborates a void of criteria for its preservation. Some documents, but especially the objects that arrive at both the Penitentiary Museum in São Paulo and the Archive and Museum Centre in Lisbon, come from the various units linked to Prison Services and youth assistance still in operation, but also to those closed or merged over the years, and they often bring little information, making identification a challenge. They refer mainly to ordinary prisoners, but also to young people abandoned and/or in conflict with the law, corroborating Vimont’s (2014) notion of prison heritage, which seeks to expand the understanding of the concept to something beyond ordinary prisoners, a typology linked to different confinement experiences.

In the case of works of art, graphics, and murals, identification is almost always an even greater challenge. In general, data such as authorship and date are only possible when inscribed in the works by the authors themselves. In São Paulo and Lisbon, some works contain the name and number of the prisoner, and there is a concern to record the origin of the pieces, indicating which institution they come from. Thus, the Technical Data Sheets are incomplete, and even when providing the name of the author it is impossible to locate the individual file or other corresponding records as documents are often lost or burned over the years.

Absences increase the silences. The authors are absences, with experiences denied to researchers and the audience. Both institutions have about 80 paintings and drawings. Part of the work is the result of industrial design workshops that operated in various prisons.18 If, until the eighteenth century, prison labor was linked to punishment and torture, something imposed on the detainee, in the nineteenth century, work began to be understood as a possibility for social recovery or resocialization of the sentenced, mainly by means of craft workshops, not only for adults but also for abandoned minors and/or youth in conflict with the law. The workshops were the places where inmates learned a craft, a profession, a skill. Among the concerns with the recovery/resocialization of prisoners, besides labor activities (productive or not) there was always the concern to teach crafts, professions, develop not only work skills but also artistic talents, as in the drawing workshops that gave rise to many paintings. The clashes surrounding the issue are beset by complaints about the low cost of criminal labor, as Foucault had already pointed out by citing the French workers strike of 1840, in which they accused the government of encouraging prison labor as a way to lower wages (Salla, 1994, 1999; Pessoa, 2000; Perrot, 2001; Foucault, 2002 [1975]).

Shortly after the Lisbon and São Paulo Penitentiaries were built, workshops were created for prisoners to be engaged in carpentry, locksmithery, bed-making, tailoring, etc., but some also aimed at developing the inmate’s artistic skills, mainly in drawing and painting (Salla, 1994, 1999; Adriano, 2010). In recent decades, the presence of work and artistic activities for prisoners has lessened, revealing the juncture in which a restructuring of the world of work and new, harsher perceptions of punishment for criminals is taking place. Under new guises, the proposal of resocialization through workshops and work-related activities continues to the present day, proposing paid activities to detainees or self-improvement courses. This is certainly a complex and controversial subject, which is beyond the scope of this paper, but it was necessary to address it, albeit succinctly.

The paintings belonging to the penitentiary museums, many of them the result of such activities, are commonly displayed as the creative expression of prisoners, showing that the workshops and activities proposed by the institution produced beautiful pictures made by inmates.

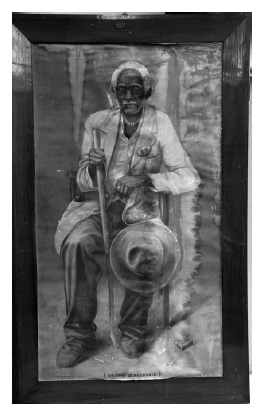

In general, the works revolve around certain common themes: religion, family (portraying women and children), landscapes and artists, and famous historical figures. One of the few cases to deviate from these themes is the oil painting “Preto Velho” (see Image 5), belonging to the collection of the Paulista Penitentiary Museum.

Copyright: Museu Penitenciário Paulista (Brazil). Painting by C. Lourenço.

Image 5 “Preto Velho”, oil painting

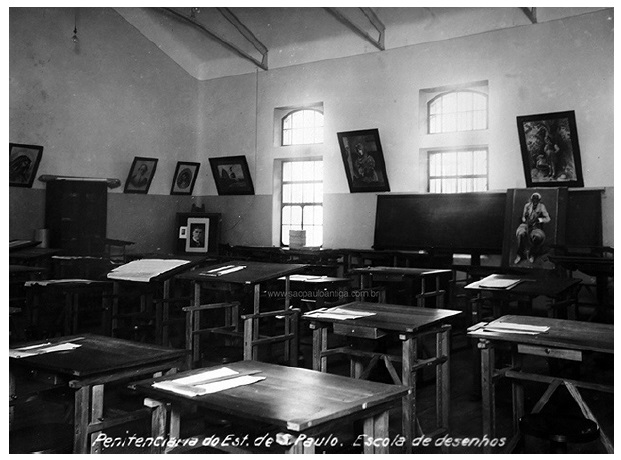

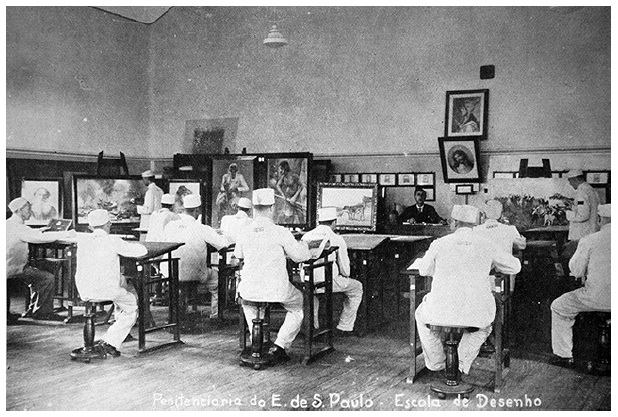

The work is signed by C. Lourenço, inmate number 426. This is the information available.19 The painting is on display at the Paulista Penitentiary Museum. It is the result of the painting workshops of the São Paulo Penitentiary, and it was painted in the 1920s. It is possible to see the work in two photographs of the Drawing School (see Images 6 and 7).

Copyright: Museu Penitenciário Paulista (Brazil).

Image 6 São Paulo State Penitentiary, Drawing School (paintings)

Copyright: Museu Penitenciário Paulista (Brazil).

Image 7 São Paulo State Penitentiary, Drawing School (classroom)

The painting recalls a very popular Umbanda entity, “Preto Velho”, one that would be known even outside the community. This spirit would present itself under the archetype of an old enslaved African, a deity considered knowledgeable and patient, portrayed in ragged robes or gowns, with a kind demeanor. As there is no information about the painter, it is not possible to know his motivations for choosing the theme. Nor is it possible to be sure whether the title given to the work was the idea of C. Lourenço or those responsible for the workshops. The figure in “Preto Velho” painted by C. Lourenço is dressed as a common urban dweller and has a thoughtful and slightly embittered expression. The traditional image of “Preto Velho”, however, would be of a man with the simplest white trousers and shirt, recognizable in Brazilian culture as associated with non-Catholic worship practices. Thus, the author’s interpretation may have been a strategy, allowing the work to go unnoticed in a context where creativity was controlled by institutional practices, and religious themes could only be associated with the Catholic Church. Through the work it is possible to conjecture about the religious practices of the author, and even his possible connection with slavery in the past, perhaps as a descendant of slaves. These assumptions bring elements that encourage reflection about the potentiality of how such insurgent collections can think about prison heritage.

Mr. “P.”

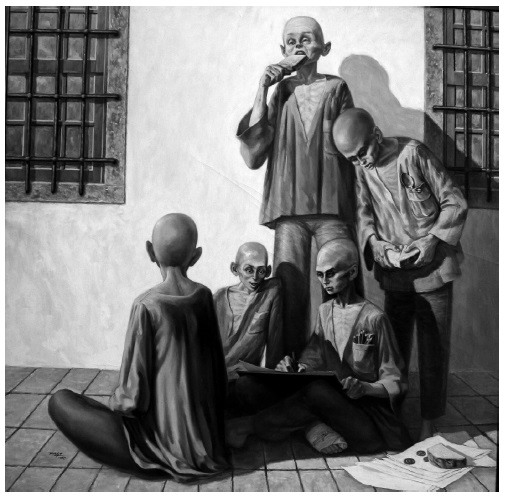

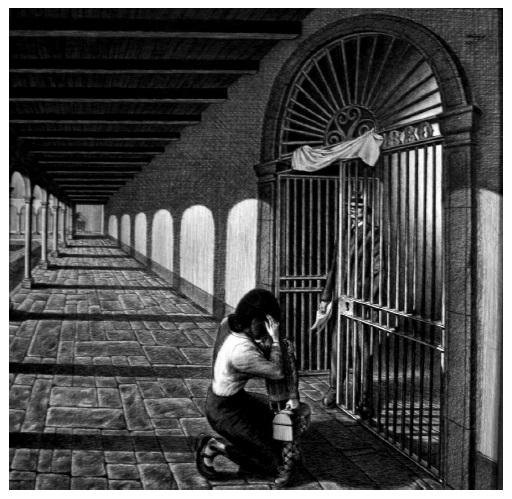

The paintings signed by Pinho are in the Archive and Museum Centre of the Directorate-General of Reintegration and Prison Services in Lisbon. There are 20 paintings20 that deal with life in confinement, showing the bars, the guards, the uniforms, the shaved heads, the refectory, the suffering, the punishment, the myriad institutional practices (see Images 8 and 9).

Copyright: Arquivo Histórico da Direção Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais (Portugal).

Image 8 “A venda da ração de pão”, oil painting (Collection Quadros do Pinho)

Copyright: Arquivo Histórico da Direção Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais (Portugal).

Image 9 “A entrada”, charcoal drawing (Collection Quadros do Pinho)

The pictures are strong, hard, disturbing. They tell a story, depict a denunciation, an attempt to sensitize or even shock the viewer. This brief initial glance allowed us to see a sequence that the current disposition did not allow us to glimpse completely. The 20 paintings held by the Archive and Museum Centre signed by “Pinho” were painted between 1987 and 1989. When I began the on-site research in early 2019, the full name of the artist was not known, and the information hitherto possible was controversial and incomplete.

A blue folder accompanied the paintings when they arrived at the Archive Museum in 2014. In it, you can find copies of part of a catalog entitled “Notes on a Painting Exhibition” and the name of the exhibition: The Fate of the Street Boy (O destino do rapaz da rua, in the original), with images of the works and texts written by the author himself. The autobiographical texts are sensitive and show that Pinho wanted the work to be read as a denunciation. But they were not signed, which raised doubts for the Museum staff, and it was possible to read remarks written in pencil in the margins of the texts: “Who wrote the texts? Was it the author himself?”. It was not sure if the person who painted the paintings had actually lived that experience, or if it was just denunciation paintings and sensitive texts woven by an outside observer. “Mr. P.”, as known to the staff of the Museum Archive, was one of the hidden absences in the vast prison collection.

To reach the author of the works, it was necessary to weave a web from a few traces, thinking the objects (the pictures) articulated to the multiple statements produced about them (Brulon, 2015). One of the first clues was given by a former employee who recalled the context of how the paintings were acquired. The works were bought by the Portuguese state, which in itself makes them unique since, to date, all that is known of this acquisition comes by buying works from an individual who has passed through the confinement spaces. And they would have been painted after the confinement experience. This also diverges with the rest of the collection, with works produced during the prison experience. The person responsible for mediation was Luís Miranda Pereira, who coordinated the Directorate-General of Tutelary Services for Minors and the Institute for Social Reinsertion in 1990s.21

The works remained for a long time at the Padre António de Oliveira Educational Center, at the Cartuxa Convent, in Caxias, a space for abandoned minors and/or youth in conflict with the law. They were kept in the so-called “museum room”, along with other works considered of historical value. Still in the 1990s, the staff were transferred to the central services of the Directorate-General of Reintegration and Prison Services, in Lisbon. In 2014, when the social reintegration and prison services merged, the paintings were transferred to technical storage located at the Lisbon Penitentiary.

In conversations that permeated the many days of research in the archive, I was informed that in 2014 a woman had made contact on behalf of her father to visit the institution in order to specifically view the works of the painter, Pinho. Here is an excerpt from Celia’s e-mail to Cristina Santos, Head of the Documentation and Historical Archive Division.

I think you already know that I have struggled to locate Mr. Pinho [...]. My aim is above all to observe them, however, when thinking about my request, I have hypothesized that they are archived and I have commented that if they no longer interest anyone, they interest me.I am interested in the fact that these paintings were made by a deceased friend and former colleague of my father’s in the reformatory I spoke of and where the dramatic reality of their childhood and many others is portrayed. During an exhibition in Porto from which I sent a copy of the prospectus, Mr. Pinho and my father now relived without hurt, all the moments that are portrayed in the paintings. [...] I would like to take my father to Lisbon to have the pleasure of seeing these paintings again, and it is in this sense that I look forward to your contact.22

The paintings requested by Celia fulfill a social function here, allowing those who lived the confinement situation to identify themselves, to feel their experience represented within the memory space. They relate to memories, connect past and present. However, the visit never took place. Luckily the email was printed, and it was archived, so I was able to contact Celia and her father, António Fernando. The interview with António Fernando23 was marked by emotional memories about the places that received the minors in Portugal in the 1930s and 1940s. He was a contemporary of Pinho in the Porto Juvenile Home, and they had met again in 1990, when the artist held the exhibition The Fate of the Street Boy, at Casa do Infante, in Porto. António Fernando remembers the emotion he felt when he saw the paintings depicting the places he had also been through, and he made a point of showing Pinho’s dedication in a folder of the exhibition he keeps to this day: “Might there be someone else who is able to talk about this exhibition besides us?”.

To investigate this further, I contacted the Porto Municipal Historical Archive, where I located a small catalog with a series of texts in which Pinho explains the 20 paintings and the motivations behind their creation:

Those who lived a childhood within walls always keep running away, always alone in the crowd, often misunderstood, pragmatic, and they may even become easily marginalized. [...] It all turned out to be a passionate theme that motivated this exhibition. And of course, all this work was done without models, serving just and only those, which the memory retained - “Figures remembered with eyes closed until suffering”. These images rolled inside me for 50 years [...]. This exhibition is the result of nine years of work. Total dedication and isolation, away from the art galleries and their exhibits, nine years of suffering at the easel, but it was worth it! Twenty 1 x 1m paintings (10 oils and 10 charcoal drawings) tell how little fortunate children aged 6 to 18 years lived.24

The texts pointed out the ways of the exhibition, the order in which the work should be exhibited, and the nine years of work, dedication, and suffering. They expressed the artist’s motivations. The anguish extinguished through painting. They reflect a moment of catharsis, “a kind of exorcism in order to make peace with that past”, as his daughter later pointed out.

The catalog also featured comments from local personalities of the time, all deceased,25 except journalist and writer José Viale Moutinho. Talking to a colleague from Porto, I learned that he used to go to a local bookstore, which is where I found him. Moutinho provided a catalog of a 1981 exhibition that showed Pinho as a landscape, portrait, and still-life painter. It also revealed that Pinho was José Joaquim de Almeida’s artistic name, and it indicated the address of Atelier Pinho, where the family still resided.

From then on, I was able to contact Mrs. Henriqueta de Almeida, the Pinho’s widow and Elisabete, the couple’s youngest daughter.26 The interview with the two took place in the tiled townhouse where the family has lived since 1964, where Atelier Pinho also operated. The place is remarkable for the numerous works of the artist: paintings, drawings, wood carvings, as well as photographs of him and his family. Everything there was a stimulus to memory. The themes of the works displayed in the atelier-house are varied: landscapes, portraits, self-portraits, still life, carved saints and wooden lampshades, etc. Other themes that look nothing like The Fate of the Street Boy.

According to his wife, Pinho “was born a painter, he was a born painter, it was an addiction he had to paint, he had to draw”. Henriqueta de Almeida has difficulty talking about the works that make up The Fate of the Street Boy and about her deceased husband’s childhood: “It was against my will that he painted [this]. He was reliving his childhood experiences, and I didn’t want him to, I was always against it”.27 According to his daughter, unlike his wife, Pinho had no problem talking about his childhood in the reformatory, even though her mother’s closest friends were against the exhibition of works related to this past. Pinho was the father of three children, two boys, and a girl. The older boy died as a child, leading the artist to seek comfort in religion, becoming part of the União-Obra de Auxílio aos Ex-Reclusos, a Christian philanthropic entity that assisted in the social reintegration of people released from prison. This experience led to contact with prison and juvenile directorates, allowing the exhibition The Fate of the Street Boy to become interesting in the eyes of the Directorate-General of Tutelary Services for Minors and the Institute for Social Reintegration, and it was finally acquired in the administration of Miranda Pereira,28 shortly before the artist’s death. Pinho’s work represented an institutional past that should not be repeated, according to the former director, who instituted it as an object of memory.

The present research made it possible to trace his biography briefly as follows: José Joaquim de Almeida was born in 1927 at Praia da Granja in Vila Nova de Gaia, and he died in 1993, in the city of Porto. He worked with printing, decoration, and screen printing. He painted landscapes, participated in solo and group exhibitions, and in the 1980s, over the age of 50, he began depicting his childhood within institutional walls. Shortly before his death in 1993, the 20 paintings that made up the exhibition The Fate of the Street Boy, held at the Casa do Infante in Porto in 1990, were incorporated into the estate of the Portuguese Institute for Social Reinsertion, by decision of the artist himself. In 2014, the paintings became part of the collection of the Archive and Museum Centre that works with the Lisbon Penitentiary.

The confined paintings denounce life in institutions that served the underprivileged in Portugal in the 1930s and 1940s. The childhood experience the artist lived as a former student of the Colégio dos Carvalhos, the Colégio dos Passos and the Santa Clara Reformatory, motivated part of José Joaquim de Almeida’s creations. As a teenager, he attended the painting course at the Faria Guimarães School of Decorative Arts in Porto, between 1941 and 1946, taking “Pinho” as his pseudonym. Pinho was the last name of the father who left the family, which prompted the artist’s mother to put him in a foster home at the age of six. The artist portrayed himself in most of the paintings. He is the boy with colored pencils in the pocket of his uniform shirt in Image 8. Pinho died in 1993 from cancer.

Brief Final Considerations

The spaces and collections analyzed here allow us to consider the specifics of the notion of prison heritage. I tried to problematize visual objects as well as others, such as murals and graphics, thinking about the weaknesses and absences that permeate these traces. One of the most prominent issues is the lack of information and the erasures it causes. The lack of information neutralizes the previous life of the objects present in the prison collections, rendering the authors absent. The works analyzed and cited here are “marginal objects” (Ramos, 2011), traces that refer to prison heritage, and what society does not wish to remember. They are vectors that encourage reflection and help to problematize the institutional collections linked to prison spaces, allowing us to weave the notion of prison heritage as a potentializing field to contemplate the experiences of those individuals who pass through these spaces and escape and transgress stereotypes.